A Comet Looms Largest, Medusa Blinks, and a Super Bright Moon Lets Bright Lights Shine!

A terrific image of Comet C/2023 A3 (Tsuchinshan-ATLAS) after sunset on Saturday, October 12, shared by Paul Whitmarsh and Jane Penny, of the Lewes Astronomical Society, and our deputy director Dr Robert Massey of the Royal Astronomical Society in the UK. The original post is at https://www.facebook.com/share/p/ZT1U7DUCQsQPmRzf/

Hello, mid-October Stargazers!

Here are your Astronomy Skylights for the week of October 13th, 2024 by Chris Vaughan. Feel free to pass this along to your friends and send me your comments, questions, and suggested topics. You can also follow me on Twitter as @astrogeoguy! Unless otherwise noted, all times are expressed in Eastern Time. To subscribe to these emails please click this MailChimp link.

If you’d like me to bring my Digital Starlab portable inflatable planetarium to your school or other daytime or evening event in Simcoe, Grey, and Bruce Counties, or deliver a virtual session anywhere, contact me through AstroGeo.ca, and we’ll tour the Universe, or the Earth’s interior, together! My book with John A. Read entitled 110 Things to See With a Telescope is a guide to viewing the deep sky objects in the Messier List – for both beginners and seasoned astronomers. DM me to order a signed copy!

This week will be busy! The moon will become super again while it moves through its full phase, visiting Saturn and obscuring all but the brightest stars and planets along the way – so I guide you to those bright lights. Comet A3 will peak in visibility for mid-northern latitudes, some meteors should show up, the variable star Algol will fade at a convenient time, and zodiacal light might be glimpsed. Read on for your Skylights!

Happy Canadian thanksgiving! Unlike many of the holidays I mention, thanksgiving celebrations are not scheduled by the stars, sun, or moon. Although the next holiday, Halloween, is!

Comet Tsuchinshan Update

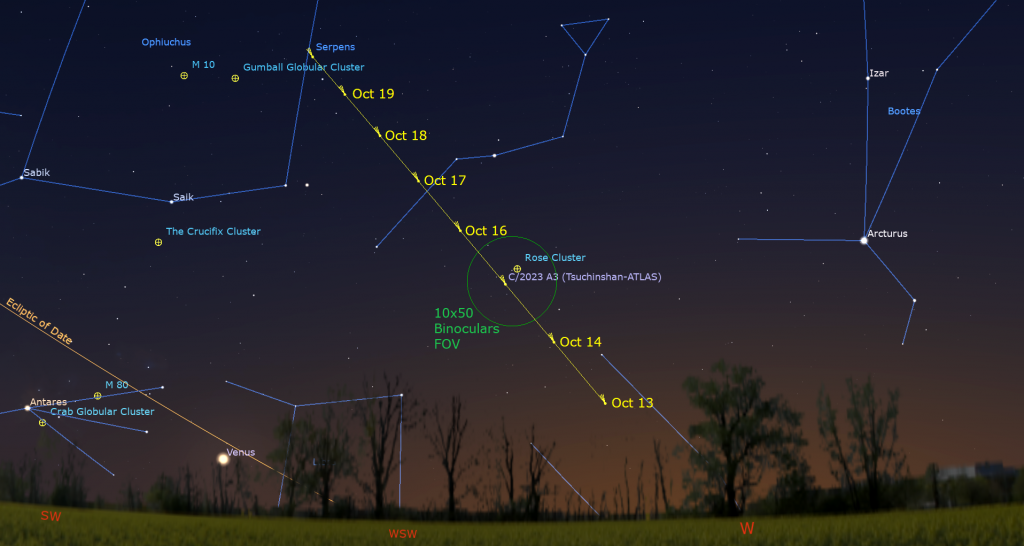

This will be the best week to view the prominent comet named C/2023 A3 (Tsuchinshan-ATLAS) that I have been telling you about for the past few weeks. The comet already passed the sun and is now leaving the inner solar system. On the way out, it flew closest to Earth, about 70 million km away, yesterday, on Saturday, October 12. That proximity makes the comet appear largest and brightest in the sky, from our vantage point. Now it will increase its distance from us, and the sun’s warmth, every day.

For the next few weeks the comet will appear in the western sky right after sunset. During this week, it will increase its angle away from the sun by several finger widths per day, allowing it to set about 20 minutes later night-to-night and lingering into a darker and darker sky. That will make it relatively easy to see in binoculars and probably with your unaided eyes, too – as long as the sky to the west is unobstructed and free of clouds and haze.

The comet’s orbital motion will carry it up and to the left (or celestial east) each night. Tonight (Sunday), search about 2.3 fist diameters to the right and a little ways higher than brilliant Venus. On Monday it will sit almost exactly midway between Venus and the bright star Arcturus. On each night thereafter it will migrate to the upper left. On Tuesday night, imagers can catch a photo of the comet passing close to the big globular star cluster Messier 5 aka the Rose Cluster. Binoculars will show that cluster, too. On Saturday and Sunday, the comet will slide past the bright star Marfik in Ophiuchus (the Serpent-Bearer) and set around 10 pm, well after dusk. Yay!

Tonight, start looking for the comet around 7 pm local time. Venus will set at 8 pm, but Arcturus will remain until in view after the comet sets. On Wednesday, the comet will be at the same height as Arcturus, then a bit higher than the star every night. Expect to see the comet as a bright little star surrounded by a fuzzy halo. The slender tail will extend up to the left, away from the sun. Cameras and binoculars will work best. See if you spot a thin, faint extra tail pointing down towards the right, the trail of dust left in the comet’s wake.

Fingers crossed for clear skies!

Zodiacal Light Alert

During autumn at mid-northern latitudes every year, the ecliptic extends nearly vertically upward from the eastern horizon before dawn. That geometry favors the appearance of the faint zodiacal light in the eastern sky for about half an hour before dawn on moonless mornings. Zodiacal light is sunlight scattered by interplanetary particles that are concentrated in the plane of the solar system – the same material that produces meteor showers. It is more readily seen in areas free of urban light pollution.

Between now until the full moon on October 17, look for a broad wedge of faint light extending upwards from the eastern horizon and centered on the ecliptic. It will be strongest in the lower third of the sky around the bright star Regulus in Leo (the Lion). Don’t confuse the zodiacal light with the Milky Way, which is positioned nearby in the southeastern sky.

The Moon

The moon will continue to shine brightly in the evening and late-night sky this week – a welcome sight for moon-lovers worldwide, but a rather a nuisance for stargazers. Today (Sunday), our natural night-light will rise with a gibbous phase in the late afternoon. Once the sky darkens, the yellowish dot of Saturn will appear to its left (or celestial east) in the southeastern sky, and the brightest stars of summer, Vega, Altair, and Deneb, will sparkle high in the west. I’ll guide you through a tour of the brightest stars below. The lack-lustre stars of Aquarius (the Water-Bearer) will be scattered between Saturn and the moon. Skywatchers viewing Saturn and the moon late at night, in more westerly time zones, or above the southwestern horizon before dawn on Monday, will see the moon closer to Saturn.

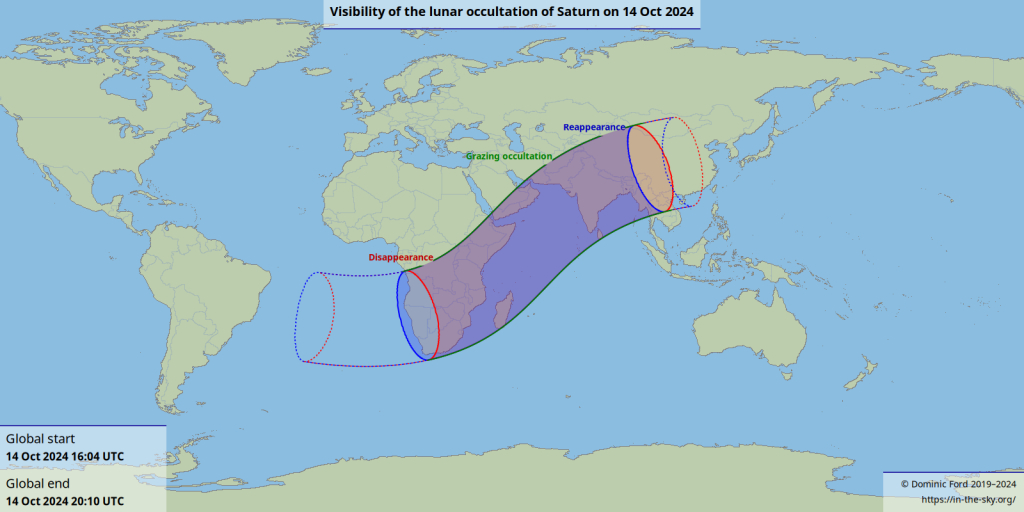

On Monday around 05:00 Greenwich Mean Time, observers located along a zone extending from southern Africa east across Madagascar, the southeastern Arabian Peninsula, and most of southern Asia, China, and Mongolia can watch the moon cross in front of (or occult) Saturn. For those of us in the Americas, the bright gibbous moon will be shining several finger widths to the left of Saturn all night long on Monday. During the night, the steady, eastward orbital motion of the moon will carry it farther from Saturn, and the diurnal rotation of the sky will lift the moon above the ringed planet before they set a few hours before dawn on Tuesday. Diurnal motion is the manner in which objects are rotated by nearly 180° clockwise from the time they rise in the east until they set in the west – all because we are viewing them from the surface of a rotating sphere. It’s especially apparent on constellations like Orion (the Hunter) and the moon’s “face”.

The moon will wax in phase and rise and set later as it increases its angle away from the sun until mid-week. Tuesday’s moon will be nearly full, overwhelming the weak stars of Pisces (the Fishes) around it.

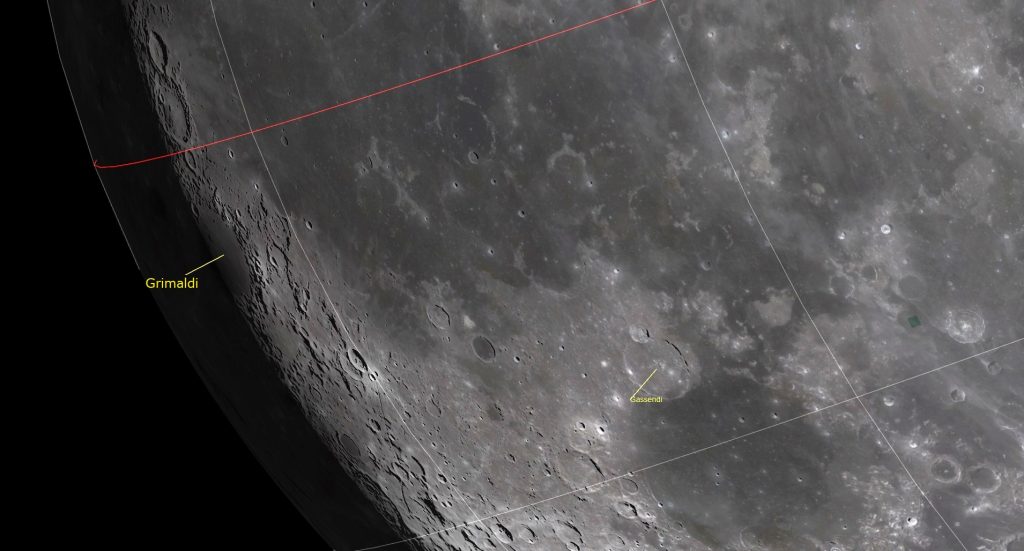

The dark-floored lunar basin named Grimaldi is a prominent, rugged, oval located near the left-hand (western) edge of the moon. It is located just south of the moon’s equator and below, or lunar southwest of, the large, dark patch of Oceanus Procellarum, the Sea of Storms. The 175 km diameter basin is easy to see using your unaided eyes and through binoculars and telescopes. On Tuesday night the severely curved pole-to-pole terminator will fall just to the west of the crater, accentuating its complex, pitted rim and some subtle wrinkle ridges on the basalts of its eastern floor. The 22 km wide fresh crater named Grimaldi B on the basin’s northern edge is visible under magnification. Grimaldi will be fully illuminated from Wednesday night onward.

The extremely bright moon will move into central Pisces (the Fishes) on Wednesday night. The full moon of October will occur at 7:26 am EDT, 4:26 am PDT, or 11:26 GMT, on Thursday, October 17. In the Americas the moon will look full on both Wednesday night and Thursday night, but magnified views will reveal a slim rind of shadow along its right and left rim, respectively, from one night to the next.

This full moon is traditionally called the Hunter’s Moon, Blood Moon, or Sanguine Moon. The Anishinaabe people of the Great Lakes region call it Binaakwe-giizis, the Falling Leaves Moon, or Mshkawji-giizis, the Freezing Moon. The Cree Nation of central Canada calls it Opimuhumowipesim, the Migrating Moon – the month when birds are migrating. The Haudenosaunee (Iroquois / Mohawk) of Eastern North America use Kentenha, the Time of Poverty Moon.

Full moons in October always shine in or near the stars of Cetus (the Whale) and Pisces. With the moon passing perigee, its closest approach to Earth for the month, only 10.5 hours prior, this full moon will also be the third and largest of four consecutive supermoons in 2024. It will appear about 6% larger and 16% brighter than an average full moon, cross the sky from sunset to sunrise, and will produce large tides around the world. I wrote in detail about the supermoon phenomenon last month here.

When that super, full moon rises after sunset on Thursday, it will be shining below the brightest stars of Aries (the Ram). From then on, it will be approaching the sun from the morning half of the sky, so it will be waning in phase – with darkness invading its disk from its right-hand (eastern) limb inwards – and lingering longer into the morning daylit sky.

On Friday night, the waning gibbous moon will commence a two-night visit with Uranus and the Pleiades star cluster, but the moonlight will mostly obscure them. On Saturday night, the slightly less-bright moon will slide into Taurus (the Bull) and shine several finger widths to the lower left (or celestial east) of the Pleiades, which is also known as Messier 45, the Seven Sisters, the Anishnaabe’s Bugonagiizhig or Hole in the Sky, and the South Pacific islander’s Matariki. While the cluster’s stars will be hard to see against the moon’s glare, hiding the moon beyond the lower left edge of binoculars will reveal them. The cluster is a highlight of the autumn/winter sky.

Around mid-evening on next Sunday, October 20, the bright, waning gibbous moon will rise in the east with brilliant Jupiter shining a palm’s width to its lower right (or 6 degrees to its celestial southwest). The prominent star Elnath, which marks the northern horn tip of Taurus (the Bull), will sparkle just to the lower left of the moon. The trio will shift into the southwestern sky by dawn. By then the moon will shine extremely close to Elnath. If you head outside between the wee hours and dawn, the bright ring of stars forming the gigantic Winter Hexagon asterism will surround Jupiter and the moon. Jupiter will spend the coming year wandering inside the hexagon, while the moon will pass through it monthly.

Night’s Brightest Lights

During the latter part of October, the brightest constellations of the year will be climbing the eastern sky in late evening. Going forward, they will arrive about half an hour earlier with each passing week! Many of those constellations contain two or more very bright stars. Meanwhile, quite a few of the bright summer stars are still in the western sky after dusk – mainly because the earlier sunsets are keeping them in view even though they are creeping closer to the sun every day. Some call this “the Summer Triangle effect”. (In contrast, the later sunsets of early spring shorten our viewing time for the spring evening constellations and the galaxies that they host.)

While most of the sky’s delights are lost when a bright moon shines, the brightest stars are still in view on moonlit nights, even under mildly light-polluted skies. Once Sirius rises in the east-southeast at about 1:30 pm local time this week (at 10:30 pm by mid-November), six of the top ten brightest stars in the entire night sky will be visible to observers at mid-northern latitudes worldwide. Let’s tour the brightest stars of mid-October. (I’ve put their brightness rankings in parentheses – not counting the sun.)

Even before the sky has fully darkened this week, around 7:30 pm for example, look low over the western horizon for orange-tinted Arcturus (4th brightest) in Boötes (the Herdsman). The bent handle of the Big Dipper, which sits low in the northwestern sky after dusk, “arcs to Arcturus”. Arcturus’ name comes from the phrase “follower of the bear” because it chases Ursa Major (the Big Bear) around the sky – and it shares a root with the word “arctic”. As a bonus, comet c/2023 A3 (Tsuchinshan-ATLAS) will be located about two fist diameters to Arcturus’ left (or 24° to the celestial southeast)!

The three bright, white stars of the Summer Triangle will glimmer high up in the western sky. They’ll actually continue to be visible, albeit lower and lower each night, until mid-January! If you face west during mid-evening, very bright Vega (5th) in Lyra (the Harp) will be more than halfway up the western sky. Altair (12th) in Aquila (the Eagle) will be off to Vega’s left (or celestial south). That star will set as brilliant Sirius rises. You’ll find Deneb (19th) in Cygnus (the Swan) shining more than two fists above and between Vega and Altair.

Turning to face south, mid-northern latitude observers with a low southern horizon should be able to see Fomalhaut (18th) in Piscis Austrinus (the Southern Fish). Big telescopes have been able to take pictures of a dusty protoplanetary disk that encircles Fomalhaut. People living at more southerly latitudes get to see Fomalhaut higher in their sky. That star will be easiest to see while its highest due south around 10:30 pm local time.

The rest of the brightest stars are in the eastern sky. Prominent yellowish Capella (6th), in Auriga (the Charioteer) is the brightest and highest of the eastern sky’s bright lights. Although it is circumpolar (i.e., it never sets) for everyone north of the 44th parallel, it doesn’t tend to climb higher than landscape obstacles until about 9 pm local time. Capella’s spectral class, and therefore its colour, is similar to our sun’s.

The next bright bauble to rise will be reddish Aldebaran (14th), which marks Taurus, the bull’s southern eye. The star is located three fist diameters to the lower right (or 30 degrees to the celestial south) of Capella. It will be rising over the east-northeastern horizon at about 9 pm local time this week. Its name arises from an Arabic expression for “the Follower” because it rises after the Pleiades cluster, the stars of which will appear as a glittering patch a generous fist diameter above Aldebaran.

Here’s where a bit of confusion might set in. This year, the planet Jupiter, which shines far brighter than any of the stars I’ve been highlighting, will gleam to the right of Capella and below Aldebaran. It’ll hang out with those stars until they all disappear into the western sunset next spring.

The next bright star to rise, at about 11 pm local time, will be orange-red Betelgeuse (normally 10th). This red giant star marks the eastern shoulder, or armpit, of Orion (the Hunter). During the winter of 2019-2020 Betelgeuse dimmed dramatically, lowering its ranking for a while. (Orion’s other shoulder star Bellatrix ranks 26th.) Someday Betelgeuse will explode in a supernova, temporarily raising it to the top of the leaderboard and later replacing Orion’s sparkling shoulder with a dim expanding nebula.

Orion’s three-starred belt will catch your eye – both because those stars are reasonably bright (29th, 32nd, and 67th) and because of their arresting pattern.

The next bright autumn star to rise, shortly after Betelgeuse, will be Pollux (17th), which marks the head of the eastern (and lower) head of Gemini‘s “twins”. Pollux is positioned about 3.4 fist diameters below (or 34 degrees to the celestial southeast of) Capella. The star shining about four finger widths above Pollux is Castor (24th). To help you remember which is which, note that Castor comes first in an alphabetical list and also rises before Pollux. The two stars must be fraternal twins since they have differing colours and brightnesses. Castor splits into a nice multiple star when viewed through a backyard telescope.

Blue-white Rigel (7th), which marks the western foot of Orion, will appear over the east-southeastern horizon around the same time that Pollux rises. After that, another interloper will appear. The prominent reddish dot of Mars will rise at about 11:30 pm local time. You’ll notice that it’s about the same brightness and colour as Betelgeuse – for now. During the coming weeks, Mars will slide eastward away from the winter constellations and into the spring stars, all the while brightening as it approaches closer to Earth.

We have 90 minutes to wait for the final bright stars to appear. Procyon (8th), in Canis Minor (the Little Dog) will shine below and between Gemini and Orion after 1 am local time. Remember that all of these times will arrive three hours earlier come mid-November when we add the end of Daylight Saving time.

Our final two bright stars to rise are both part of Canis Major (the Big Dog). The “Dog Star” Sirius (1st) will be hard to miss once it rises at about 1:25 pm local time. The star will climb to its highest point, about a third of the way up the southern sky at sunrise. In fact, all of these spectacular stars and planets will be worth a peek outside at 6:30 am every morning!

Even though Sirius is the brightest star in the heavens, not counting the sun, Jupiter and Venus easily outshine it. If you are walking through your darkened house in the middle of the night, Sirius is likely to catch your eye out a south-facing window because it never climbs very high. Sirius’ brightness and low position in the sky combine to produce spectacular flashes of colour as it twinkles. Finally, at 12:30 am, the star Adhara (22nd) will appear below Sirius. Adhara marks the dog’s rear leg and gives this little constellation two bright stars.

It’s fun to ponder, which is the brightest constellation? I’d argue that it’s Orion, for its abundance of bright stars. The southern hemisphere constellation of Crux (the Southern Cross) and our Canis Major rank next in line. All three of those constellations contain two each of the top 22 brightest stars.

Stars shine brighter for two primary reasons. They can be inherently more luminous (i.e., emitting more visible light) and/or they can be closer to us. Two of the stars noted above, Sirius and Procyon, are only about 10 light-years away from our sun. Vega, Altair, Pollux, and Fomalhaut are less than a few dozen light-years away. Betelgeuse is 640 light-years away. Amazingly, Deneb is a whopping 2,600 light-years away! It’s producing a prodigious amount of visible light to appear so bright from such a distance!

The Wikipedia list of brightest stars is at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_brightest_stars.

The Planets

We can enjoy some planets while we are outside chasing the comet – but don’t bother with the planets until after you have seen the comet! Priorities! The comet will soon enough be gone. From now until February, we’ll have four planets to see in the evening, and two more from late-night to dawn.

Mercury will lurk above the west-southwestern horizon after sunset this week – but it won’t be easy to see unless you live close to the tropics or in the Southern Hemisphere.

Brilliant, magnitude -3.9 Venus will dominate the western sky after sunset, though it will be rather low in the sky. This week, our sister planet will set about 80 minutes after the sun for mid-northern latitude observers. Immediately after the sun has set, turn and face southwest and look low in the sky for a brilliant, gleaming white dot. (If you see something bright that is moving left or right, it’s an airplane.) Venus is returning from a trip beyond the sun, so it is simultaneously increasing its angle from the sun, waning in illuminated phase, and growing larger in telescopes. It’s not setting any later each night because its eastward orbital motion is opposite to the daily westward drift of the sky. This week Venus will set at about 8 pm local time.

Venus will be higher and easier to see for anyone living closer to the tropics. No matter where you live, it will be safe to view it through binoculars or a telescope after the sun has completely disappeared. In a telescope the planet will show a blurry (due to the extra air you are looking through) 81%-illuminated disk – like an over-inflated rugby ball.

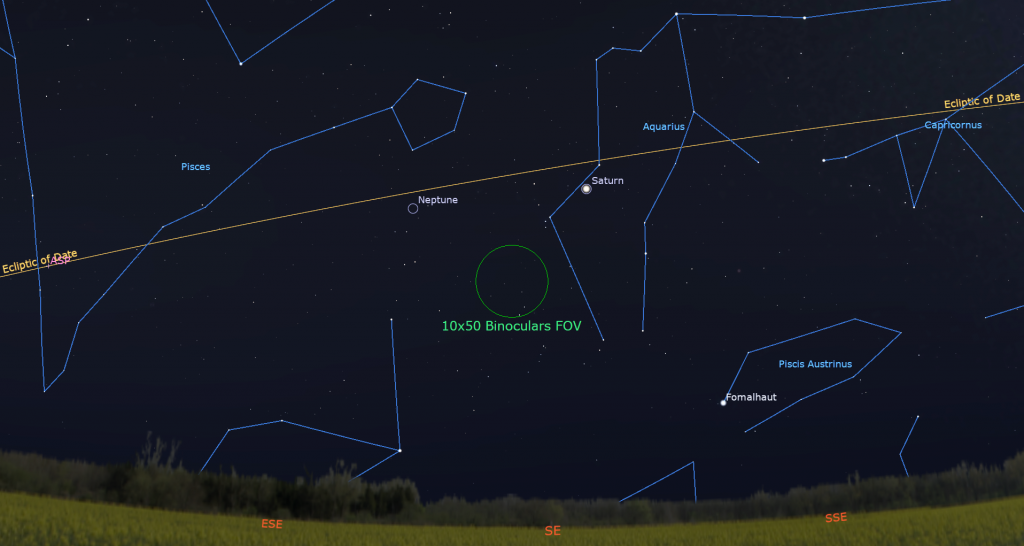

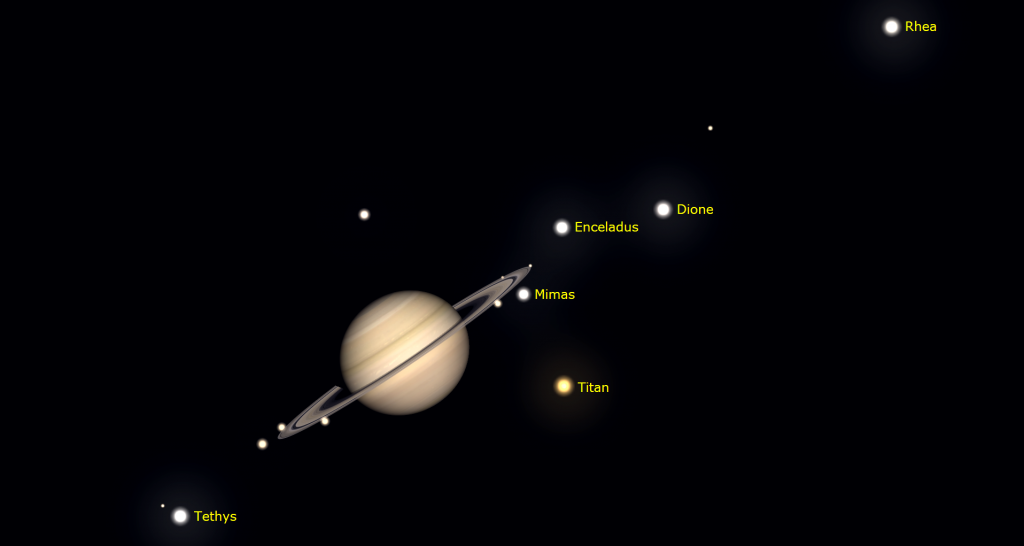

Once the sky has darkened more and you have finished looking for the comet, turn to the southeast to spot Saturn shining in the lower part of the sky. The ringed planet will rise in the east in late afternoon and then cross the southern sky all night long with the lacklustre stars of Aquarius (the Water-Bearer) that surround it. Saturn will set the west during the wee hours. On Sunday and Monday the bright waxing gibbous moon will shine near Saturn and occult it, as I described above. On any night, binoculars will show you a bent-line trio of stars collectively named Psi Aquarii sparkling to Saturn’s lower left. See if you can tell that the lower two are white, while the higher one is golden. Two redder stars named Phi and Chi Aquarii will appear to Saturn’s left and lower left, respectively.

Saturn’s extremely thin rings effectively disappear when they become edge-on to Earth every 15 years. They will do that in late March (while in the pre-dawn sky), so the rings already look like a thick line drawn through the planet. Good binoculars can hint that Saturn has rings. Any size of telescope will show the rings and some of Saturn’s larger moons. In most years, Saturn’s moons are spread all around the planet – unlike Jupiter’s Galileans moons, which are always in a line – but Earth’s perspective of the Saturn system this year and next year is making its moons line up with the rings.

Saturn’s largest and brightest moon Titan never wanders more than five times the width of Saturn’s rings from the planet. The much fainter moon named Iapetus “eye-YA-pet-us” can stray up to twelve times the ring width during its 80-day orbit of Saturn. The next brightest moons Rhea “REE-ya”, Dione “Dee-OWN-ee”, Tethys “Teth-EES”, Enceladus “En-SELL-a-dus”, and Mimas “MY-mass” all stay within one ring-width of Saturn. You may be surprised at how many of those six you can see through your telescope if you look closely when the sky is clear, dark, and calm.

During this week, Titan will move from Saturn’s lower left (or celestial east) until Friday, pose closely below Saturn on Saturday, and then just to the upper right of Saturn (or celestial west) on next Sunday night. (Remember that your telescope will probably flip the view around.) The rest of the moons will be tiny specks in a line near the rings. Earth’s perspective of the Saturn system will also cause Saturn’s moons and their small black shadows to frequently cross its disk – but you’ll need a very high quality telescope to watch those.

Saturn is being followed across the sky every night by distant blue Neptune, but viewing that planet requires a large pair of binoculars or a decent backyard telescope, and less moonlight than we’ll have this week. Like Saturn, Neptune will be visible all night long. Slow-moving Neptune will spend all of this year in western Pisces (the Fishes). During evening it’s about 1.4 fist widths to the lower left (or 14° to the celestial ENE) of Saturn and a palm’s width below the circle of stars that forms Pisces’ western fish. Use binoculars to find the upright rectangle formed by the medium-bright stars 27, 29, 30, and 33 Piscium. Neptune will be the bluish, dull “star” sitting about two finger widths above (or 2° celestial north of) that box.

The blue-green planet Uranus will clear the eastern treetops by about 9 pm local time. Slow-moving Uranus will remain positioned about a palm’s width to the right (or celestial south) of the bright little Pleiades star cluster in Taurus (the Bull) until 2027! Uranus will become high enough for decent views in binoculars or a backyard telescope after 10 pm – but those times will advance every week and Daylight Saving time will end soon, too. To get you in the vicinity of Uranus, look for the bright star Menkar shining 2.2 fist diameters to the right of the Pleiades. Uranus will be on the line joining the bottom star of the Pleiades to Menkar.

If you head outside or look out an eastern window after 10:30 pm, you’ll easily see brilliant Jupiter climbing the eastern sky. The planet will rise around 9:15 pm local time and climb to a point very high in the southwest by sunrise. The largest planet will wander between the horns of Taurus (the Bull) for the next few months and shine about a fist’s width to the left (or 12° to the celestial ENE) of the bull’s brightest star, reddish Aldebaran. Jupiter recently commenced a westward retrograde loop that will last until early February. You can notice Jupiter’s reversed motion over the coming weeks by comparing its position to the bright horn-tip stars Elnath and Zeta Tauri to its upper left and lower left, respectively. Jupiter’s retrograde loop will be a fist’s diameter in width, but the bull’s horns are half again as long.

Any binoculars will show Jupiter’s four Galilean moons named Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto lined up beside the planet. Those moons complete orbits of the planet every 1.7, 3.6, 7.2, and 16.7 days, respectively. If you see fewer than four moons, then one or more of them is crossing in front of or behind Jupiter, or hiding in Jupiter’s dark shadow – or two of the moons are very close together, or one moon is eclipsing or occulting another one. All of the moons will gather to one side of the planet next Sunday night.

Even a small, but decent quality telescope can show you Jupiter’s dark belts and light zones, which are aligned parallel to its equator. With a better grade of optics, Jupiter’s Great Red Spot, a cyclonic storm that has raged for hundreds of years, becomes visible for several hours when it crosses the planet every 2nd or 3rd night. For observers in the Americas, that GRS will cross Jupiter’s disk late on Sunday, Tuesday, Thursday, and next Sunday night, and before dawn on Monday, Thursday, and Saturday morning. If you have any coloured filters or nebula filters for your telescope, try enhancing the spot with them.

From time to time, observers with good quality telescopes can watch the black shadows of the Galilean moons travel across Jupiter’s disk. In the Americas, the small shadow of Europa and the great red spot will cross near Jupiter’s equator on Thursday morning, October 17 between 5:03 am and 7:30 am EDT (or 09:03 to 11:30 GMT).

Mars will be rising around 11:30 pm local time this week, but your best bet for seeing it will be while is shining very high in the southeastern sky before sunrise. Mars will be the bright reddish object located between Gemini’s twin stars and the bright star Procyon, and about three fist diameters to Jupiter’s left (or celestial east). Mars’ relatively faster orbital motion will increase its separation from Jupiter a little more each morning. If you are under the stars before morning twilight, you’ll notice the bright winter constellations (Auriga, Taurus, Gemini, Orion) surrounding Jupiter. At the end of October, Mars will escape Gemini’s embrace and enter Cancer (the Crab) for a “spell”.

Mars will become hidden by the morning twilight long before brilliant Jupiter does. In a telescope, the red planet will appear as a small, rusty-coloured disk. Its position on the far side of the sun from Earth, 169 million km from Earth and closing, has kept the planet looking small, but it is growing and brightening every week. This week, Mars will only be 88%-illuminated because its angle from the sun is 91°.

Medusa’s Eye Pulses

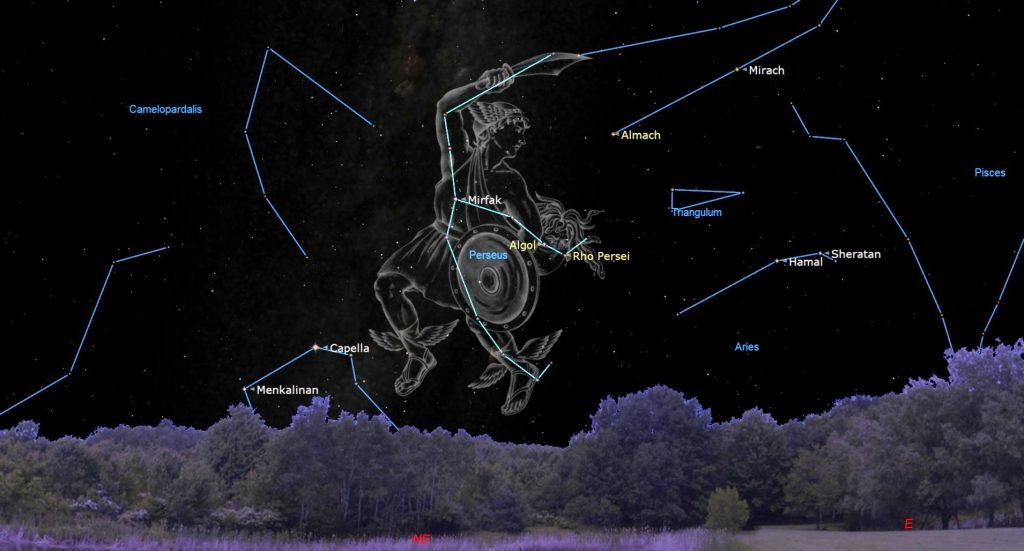

In the constellation of Perseus (the Hero), the star Algol, also designated Beta Persei, marks the glowing eye of Medusa from Greek mythology. The star is among the most accessible variable stars for skywatchers. During a ten-hour period that repeats every 2 days, 20 hours, and 49 minutes, Algol dims by a third and then re-brightens when a companion star with an orbit nearly edge-on to Earth crosses behind the much brighter main star, reducing the total light output we perceive. Algol normally shines at magnitude 2.1, similar to the nearby star Almach in Andromeda (the Princess). But while dimmed to minimum brightness, Algol’s magnitude 3.4 is almost the same as the star Rho Persei (ρ Per), which shines just two finger widths to Algol’s lower right (or 2.25 degrees to the celestial south).

On Monday evening, October 14 at 8:46 pm EDT or 00:46 GMT, Algol will be at its minimum brightness in the lower part of the northeastern sky. Five hours later the star will return to full intensity from a perch nearly overhead.

Meteor Watch

The bright moon this week will hide all but the brightest shooting stars from two showers that are approaching their peak nights. It will still be worth looking up, though! The Orionids will build to a peak on October 20-21, and the Southern Taurids will reach its maximum on November 4-5. In both cases the meteors will appear to streak away from (or radiate) from the eastern sky, where those two constellations will rise late at night. I’ll share more info about meteor showers next week. In the meantime, watch for extra meteors next Sunday morning.

Public Astronomy-Themed Events

Every Monday evening, York University’s Allan I. Carswell Observatory runs an online star party – broadcasting views from four telescopes/cameras, answering viewer questions, and taking requests! Details are here. They host in-person viewing on the first clear Wednesday night each month. Other Wednesdays they stream views online via the observatory YouTube channel. Details are here.

At 7:30 pm on Wednesday, October 16, the RASC Toronto Centre will livestream their free monthly Speaker’s Night Meeting. The speaker will be Cassia Bond, Physics MSc. Candidate at York University. Her topic will be Galactic Archaeology: Exploring the Galaxy’s History with Chemical Abundances. Check here for details and watch the presentation at https://www.youtube.com/rasctoronto/live.

On Saturday, October 19 from 8:30 to 10:30 pm EDT, the in-person Astronomy Speakers Night program at the David Dunlap Observatory in Richmond Hill, Ontario will feature Dr. John Moores, planetary scientist, author, and an associate professor at York University in the Centre for Research in Earth and Space Science. His talk will be Daydreaming in the Solar System.After the presentation, participants will view interesting celestial objects through telescopes on the lawn (weather permitting). More information is here and the registration link is at ActiveRH.

Keep your eyes on the skies! I love getting questions and requests. Send me some!