Departing Moon Brightens Night, the Seasons Switch, Jupiter Shows Spots, Medusa Opens an Eye, and More Meteors!

This image of the beautiful open star cluster around the bright star Mirfak in Perseus was taken by Martin Gembec of the Czech Republic in 2007. Mirfak dominates the centre, with the stars of the cluster, also known as Melotte 20, the Alpha Persei Moving Group, and the Little Cloud of Pirates, sprinkled mainly to Mirfak’s lower left. Polaris is out of frame at top. The image spans 4 degrees left-to-right, or several finger widths, in the sky, ideal for viewing with unaided eyes or through binoculars. Source Wikipedia and https://astrofotky.cz/gallery.php?show=MaG/1499021706.jpg)

Happy Solstice, Stargazers!

Here are your Astronomy Skylights for the week of December 15th, 2024 by Chris Vaughan. Feel free to pass this along to your friends and send me your comments, questions, and suggested topics. You can also follow me on Twitter as @astrogeoguy! Unless otherwise noted, all times are expressed in Eastern Time. To subscribe to these emails please click this MailChimp link.

If you’d like me to bring my Digital Starlab portable inflatable planetarium to your school or other daytime or evening event in Simcoe, Grey, and Bruce Counties, or deliver a virtual session anywhere, contact me through AstroGeo.ca, and we’ll tour the Universe, or the Earth’s interior, together! My book with John A. Read entitled 110 Things to See With a Telescope is a guide to viewing the deep sky objects in the Messier List – for both beginners and seasoned astronomers. DM me to order a signed copy!

The December solstice brings astronomical winter to the northern hemisphere. Following Sunday morning’s full phase, the moon will rise later and linger into the morning sky, where it will pass close to Mars. I highlight a sight in Perseus and I invite you to watch Algol vary in brightness and keep an eye out for Ursids meteors. We have four bright planets to see in the evening, including Jupiter hosting many shadow transits. Mercury enters the pre-dawn east. Read on for your Skylights!

‘Tis the Seasonal Change

Happy Holidays, everyone! Or, as we astronomers say, “Have a Happy Solstice and a Merry Perihelion!”

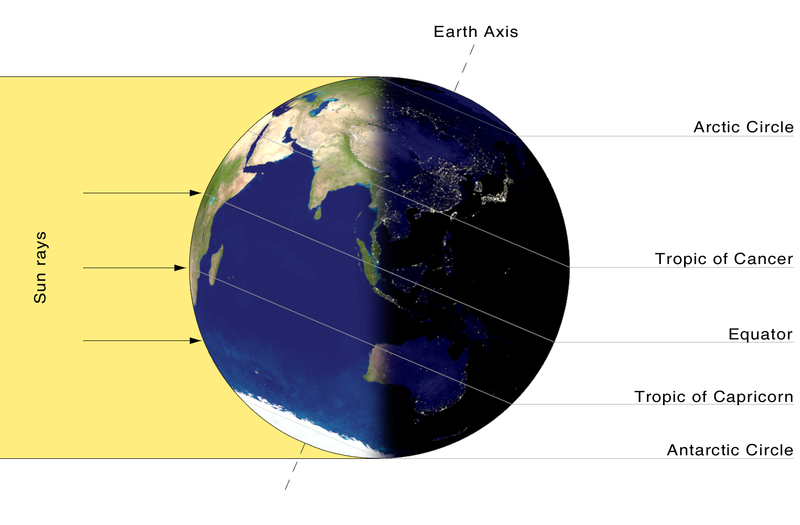

The December or winter solstice, will officially occur on Saturday, December 21 at 4:21 am EST and 1:21 am PST, which converts to 09:21 Greenwich Mean Time. At the solstice, the northern pole of Earth’s axis of rotation will be tilted by its maximum amount of 23.5° away from the sun, and the sun’s highest point in the daytime sky, which always occurs at local noon, is lower than on any other day of the year. That’s because the sun is farthest south of the celestial equator in the sky. (Astronomers call a celestial object’s highest position in the sky its culmination.)

Astronomically, the sun will also reach its greatest southern declination and its greatest angle from the celestial equator. The observation that the sun temporarily stopped moving in declination (its north-south component of motion compared to the fixed stars) on that date is reflected in the name solstice, which arises from the Latin expression sol sistere, ”the sun is standing still”.

At the December solstice, the points on the horizon where the sun rises and sets are shifted well south of east and west, so the arc that the sun traces out across the daytime sky is shorter than on any other day of the year – requiring the least amount of time to make that crossing. With noon still pinned at mid-day, it’s the sunrise and sunset times that are later and earlier, respectively – so Northern Hemisphere dwellers receive the shortest duration of daylight and the longest night for the year. I’ll post some diagrams of the geometry here.

The daytime arc of the sun continues to shorten as you move farther north on Earth – until you reach the Arctic Circle latitude at 66°33′48.4″ North. At sea level anywhere along that ring around Earth, the sun won’t rise at all on the solstice – but you would still experience a twilit sky during the noon hour. Residents (Santa and the Elves, perhaps?) living north of about latitude 80° N experience 24 hours of complete darkness. That lasts until the sky begins to brighten ahead of the March equinox.

The sunlight that northern hemisphere dwellers receive this at time of year is weaker in intensity because it’s spread over a larger area, just as a flashlight beam looks dimmer when you shine it obliquely at a wall as opposed to directly at it. Try it!

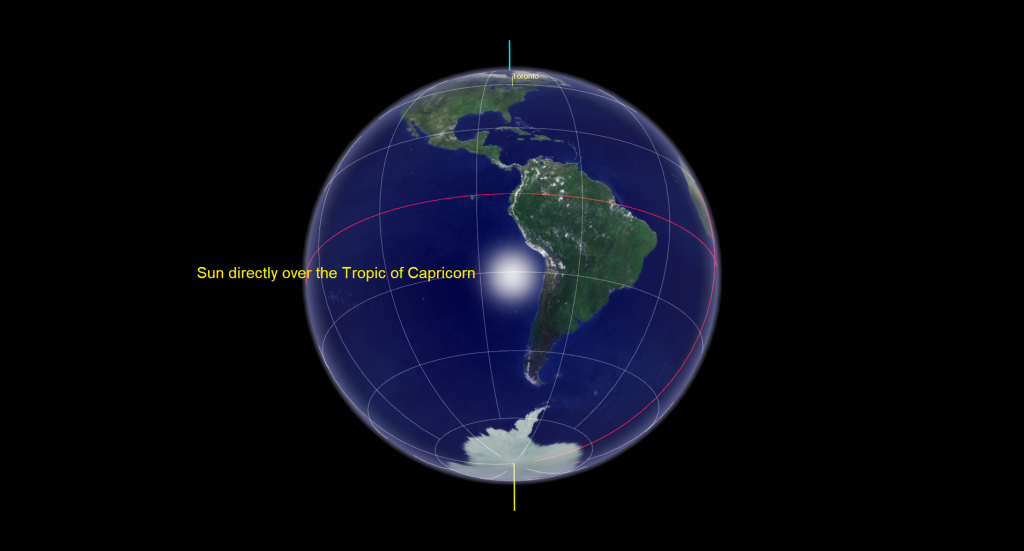

On the December solstice, the sun will be directly overhead at noon if you live along 23° 26’ 11.2” S latitude, otherwise known as the Tropic of Capricorn. The sunlight’s intensity weakens more and more as you travel farther from that latitude. (The Tropic of Cancer works the same way for the Southern Hemisphere, but on the June solstice.) In antiquity, when those tropics first became understood by astronomers/astrologers, the sun resided in those two constellations on the solstices. The precession (or slow wobble) of the Earth’s axis of rotation has shifted the celestial positions of the sun at the solstices and equinoxes, varying the precise latitude of the two tropic rings.

The solstice marks the beginning of winter for the Northern Hemisphere – but not winter weather. Fewer daylight hours and weaker sunlight results in less received solar energy (insolation) and therefore colder temperatures! That is great for astronomy if you and your equipment can stand the cold! It is not the case, as some people think, that days are colder in winter because Earth is farther from the sun (a position called aphelion). That event happens every year in early July. On the contrary – Earth’s minimum distance from the sun (perihelion) occurs every January 4, give or take a day.

After Saturday, the quantity of daylight each day will slowly start to increase again. For our friends in the Southern Hemisphere, the sun will attain its highest noon-time culmination for the year on the December solstice, and kick off their summer season. Their winter will commence six months from now, at the June solstice. The dates that equinoxes and solstices land on vary a bit due to Earth’s non-integer number of days in the solar year. If we didn’t use leap years to correct for the extra 0.26 days in each solar year, the seasons would wander around the calendar! The meteorological definition of winter is December 1 to February 28/29, corresponding to when the mean temperatures are coldest.

Some scholars think that Christmas was deliberately scheduled close to the winter solstice, and Easter close to the vernal equinox, because the early non-Christian “pagans” were already holding celebrations at that time to mark the astronomical changing of the seasons.

Meteor Shower Update

Did you see any Geminids meteors on Friday night? You can continue to watch for brilliant Geminids while the shower tapers off until December 24. The bright moon this week will interfere with them, though. True Geminids will appear to streak away from a position near Gemini’s bright stars Castor and Pollux, but the meteors can appear anywhere in the sky, so just keep looking up and around.

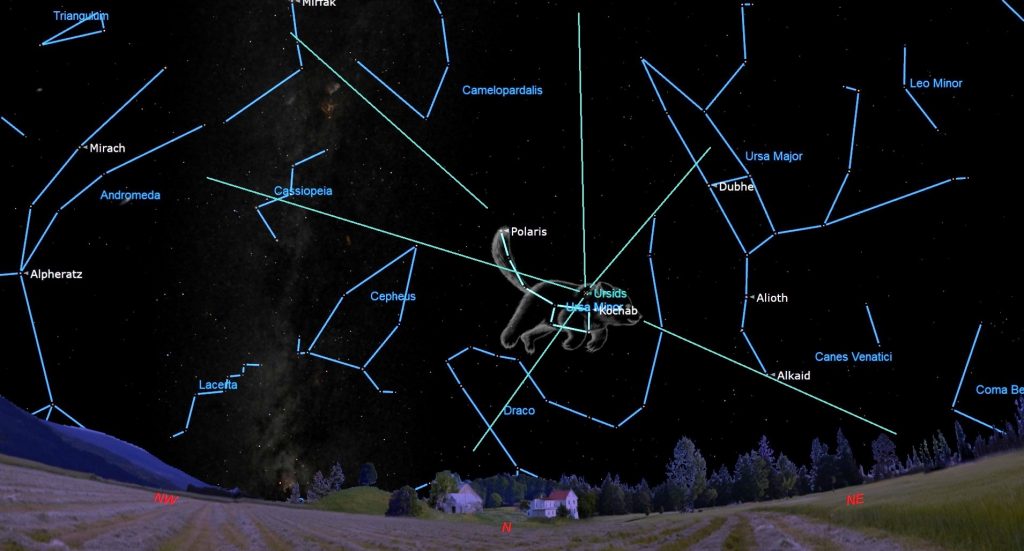

Meanwhile, the Ursids meteor shower, which is produced by particles of debris dropped by the periodic comet 8P/Tuttle will run from December 17 to 26. The weak, short-duration shower will peak (usually with only 5 to 10 meteors visible in an hour) while Earth is traversing the densest part of the debris field on Sunday morning in the Americas, but the best time to watch for Ursids meteors will be Saturday evening, December 21 before the bright, waning gibbous moon rises around midnight local time.

True Ursids will streak away from a location in the northern sky near the North Star, Polaris, but the meteors can appear anywhere in the sky – so dress warmly and head to somewhere safe and free from artificial lights. If you are outside during the wee hours, sit or stand where the moon can be hidden behind a tree or building. Good luck!

Watch Algol Brighten

On mid-December evenings the constellation of Perseus (the Hero) is climbing the northeastern sky. Just for 2024, bright Jupiter will also be gleaming to the lower right of Perseus.

Perseus’ bright star Algol represents the glowing eye of Medusa from Greek mythology. Also designated Beta Persei, it is among the most accessible variable stars for skywatchers. During a ten-hour period that repeats like clockwork every 2 days, 20 hours, and 49 minutes, Algol dims noticeably and re-brightens by about a third when a fainter companion star with an orbit nearly edge-on to Earth crosses in front of its much brighter primary, reducing the total light output we perceive. Astronomers call that arrangement an eclipsing binary star.

Algol normally shines at magnitude 2.1, similar to the star Almach (aka Gamma Andromedae) that shines 1.2 fist diameters above it. While it is fully dimmed, Algol’s brightness of magnitude 3.4 is almost identical to Rho Persei (or Gorgonea Tertia or ρ Per), the star that sits just two finger widths to Algol’s right (or 2.25 degrees to the celestial south). On Wednesday evening, December 18 at 6:47 pm EST or 23:47 GMT, Algol will be at its minimum brightness while it shines about two thirds of the way up the eastern sky, above and between the bright star Capella and brilliant Jupiter. When Algol reaches its minimum intensity five hours later, at 11:47 pm EST, it will be located high in the western sky below Capella and Jupiter.

Algol’s variations are best seen with unaided eyes or binoculars, which allow you to see its comparison stars at the same time. The website of Sky & Telescope magazine has an interactive tool to let you look up the Minima of Algol where you live. It’s at https://skyandtelescope.org/observing/the-minima-of-algol/.

Stellar Halo around Mirfak

Here’s another treat in Perseus (the Hero) that you can see any time. The outer rim of our Milky Way galaxy runs through Perseus’ stars, filling its territory with rich star clusters. The largest of those surrounds his brightest star, Mirfak (or Alpha Persei). That elderly yellow supergiant star has evolved out of its blue phase and is now fusing helium into carbon and oxygen in its core. Melotte 20, also known as the Alpha Persei Moving Group and the Perseus OB3 Association, is a collection of 100 or so young, massive, hot B- and A-class stars sprinkled over several finger widths (or 3 degrees) of the sky around Mirfak. You can easily see the cluster with your unaided eyes on a dark night, but it’s especially dazzling in binoculars. Its stars are approximately 600 light years from the sun and are moving as a group – Mirfak along with them.

The Moon

Because of this morning’s Full Oak Moon, the final one for 2024, the evenings during the first part of this week will be too moony for stargazing. As Earth’s natural night-light wanes and rises about 70 minutes later every day, we’ll migrate into stargazing mode for the coming weekend and beyond into Christmas.

Tonight (Sunday) at sunset the moon will look enormous and full while it perches above the northeastern horizon. That’s an illusion though – you can always cover the entire moon with the tip of your pinky finger held at arm’s length – even supermoons. The Moon Illusion, as it’s known, tricks our brains into thinking the moon is larger if we see it positioned near terrestrial objects like hills, trees, and buildings. Look at it an hour later when it’s higher and it will seem to have shrunk!

Last week here I shared some tips about things to see on full moons. The moon will still be more than 99%-illuminated tonight (Sunday). Only the brightest stars like Capella and the brilliant planet Jupiter, both of which will be located above the moon on Sunday, will hold their own against the moon’s glare. Not much else will be visible unless you hide the moon behind something. Full moons shine all night long and climb as high in December at midnight as the sun does at noon in Jun, and cast similar shadows in your yard.

Look low in the eastern sky after dusk on Monday to see the bright, waning gibbous moon gleaming just to the upper right (or celestial southwest) of Gemini’s brightest stars. Golden Pollux and the brighter, whiter double star named Castor above it should still be visible against the moon’s glare. Binoculars will reveal a handful of smaller stars immediately to the left of the moon, marking where the brothers are grasping hands. Bright, reddish Mars will shine down at their lower left. As the night wears on, the moon’s eastward orbital motion will carry it closer to Pollux while the diurnal rotation of the sky will shift the constellation to the moon’s right (or celestial northwest) and put Mars above them all in the western sky on Tuesday morning for your commute to school or work.

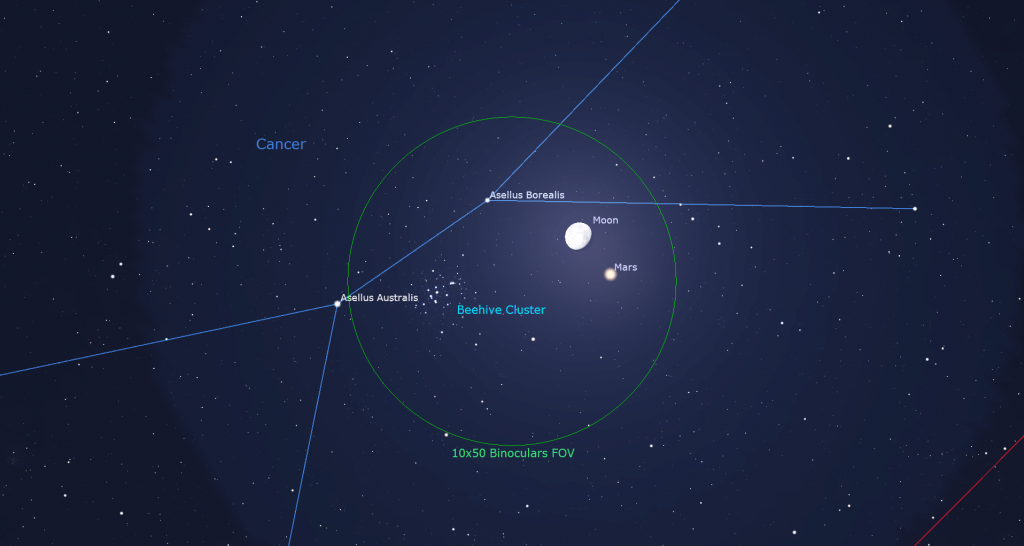

On Tuesday evening, the bright, 90%-illuminated moon will shine a short distance above (or celestial WNW of) Mars in Cancer (the Crab). The moon and the reddish planet will be close enough to share the view in binoculars, which will also show the widely scattered stars of the Beehive Star Cluster below Mars. As they cross the sky together all night long, the moon will move closer to Mars, and will actually pass in front of (or occult) the planet for observers located at far northern latitudes. In the Americas, the moon will be positioned closest above the planet around 4:30 am Eastern Time and still rather close to the planet as the duo descends the western sky before sunrise on Wednesday morning.

Wednesday’s moon, still in Cancer, will drop below (celestial east of) Mars. From Thursday to Friday the moon will traverse the stars of Leo (the Lion). That’s a spring constellation, so you’ll see those stars climbing the eastern sky from midnight onward, their queuing location before they enter the early evening a few months from now. Meanwhile, Thursday night’s moon will shine near Leo’s brightest star, Regulus.

You could instead spot Regulus near the moon, with Mars’ prominent red dot far off to its right, on Friday morning at breakfast time. By that point in the moon’s cycle, it will linger into the morning daytime sky until midday.

The moon will end this week by starting a trip through the stars of Virgo (the Maiden). The moon will complete three quarters of its orbit around Earth, measured from the previous new moon, on Sunday, December 22 at 5:18 pm EST, 2:18 pm PST, or 22:18 GMT. At its third quarter (or last quarter) phase the moon appears half-illuminated, on its western, sunward side. It will rise around midnight local time and then remain visible until it sets in the western daytime sky during early afternoon. The 7-10 days of dark, moonless evenings that follow this phase are ideal for observing the fainter stars and deep sky targets.

The Planets

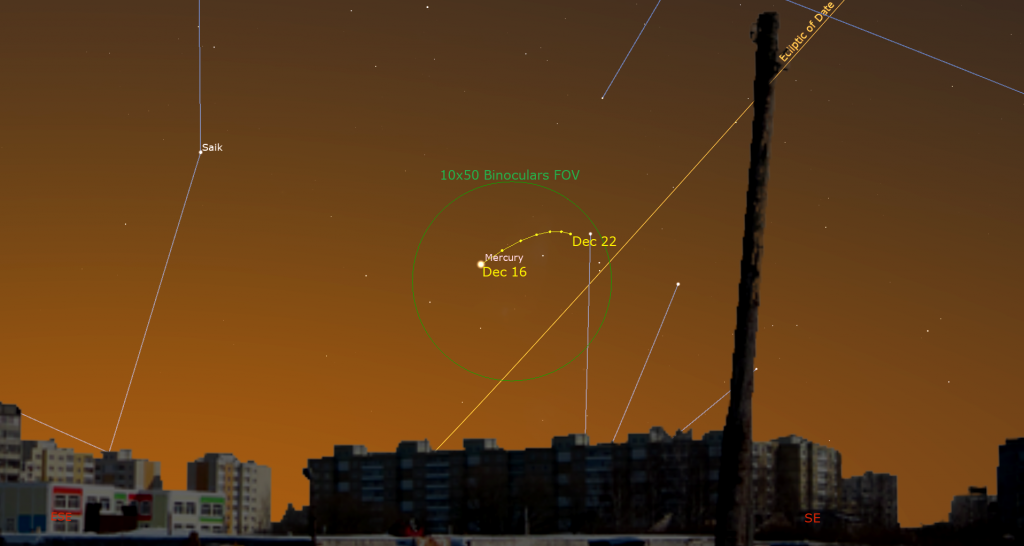

Mercury has entered the eastern morning sky. Before sunrise any morning, look for it shining low in the southeast. Viewed in a telescope, the blurry will look rather blurry due to the extra air we are looking at it through. But you should be able to see its waxing, half-moon shape. The speedy innermost planet will remain visible until well into January. Turn binoculars away from the horizon before the sun starts to rise.

The rest of the planets are in the evening sky. Venus is the very bright “Evening Star” gleaming in the western sky every evening. The planet will be visible even before the sky darkens, but the stars of Capricornus (the Sea-Goat) that surround it will appear once the sky darkens. This week Venus will set around 8:15 pm local time. When viewed through a telescope or very strong binoculars, the planet will show a waning gibbous phase.

Venus’ swing away from the sun has put it on course to kiss Saturn in mid-January. In the meantime, you’ll notice that Saturn’s yellowish, medium-bright dot is positioned less and less to Venus’ upper left (or celestial east). This week the two planets will be about three fist diameters apart. Once Venus drops into the trees in the southwest around 7 pm local time, Saturn will remain. You might also see the bright star Fomalhaut in the constellation of Piscis Austrinus (the Southern Fish) twinkling about two fist diameters below, and a little to the right, of Saturn.

Saturn and the faintish stars of Aquarius (the Water-Bearer) surrounding it will set the west around 11:10 pm local time, but you’ll have clear views of the planet in any backyard telescope only until 9:30 pm. Saturn’s bright, but extremely thin rings effectively disappear when they become edge-on to Earth every 15 years. Since we are only three months away from that, in late March, 2025, the rings already appear as a thick line drawn through the planet. Good binoculars can hint that Saturn has rings, but any size of telescope will show the rings and some of Saturn’s larger moons, too. In most years, Saturn’s moons are sprinkled around the planet, unlike Jupiter’s Galileans moons, which are always in a line. But while Earth is within months of being aligned with Saturn’s ring plane, its moons orbit inside a band parallel to the rings.

Saturn’s largest and brightest moon Titan “TIE-tan” never wanders more than five times the width of Saturn’s rings from the planet. The much fainter moon named Iapetus “eye-YA-pet-us” can stray up to twelve times the ring width during its 80-day orbit of Saturn. The next brightest moons Rhea “REE-ya”, Dione “Dee-OWN-ee”, Tethys “Teth-EES”, Enceladus “En-SELL-a-dus”, and Mimas “MY-mass” all stay within one ring-width of Saturn. You may be surprised at how many of those six you can see through your telescope if you look closely when the sky is clear, dark, and calm.

During early evening this week, Titan will start from a position just to Saturn’s left (or celestial east) tonight (Sunday) and venture a bit farther out on the same side before swinging back and passing just below (celestial south of) Saturn from Saturday to next Sunday. (Remember that your telescope will probably flip the view around.) The rest of the moons will be tiny specks in a line near the rings. Earth’s perspective of the Saturn system will also cause Saturn’s moons and their small black shadows to frequently cross its disk – but you’ll need a very high quality telescope to watch those.

Distant, blue Neptune will be located 1.3 fist widths to the upper left (or celestial ENE) of Saturn and a palm’s width to the lower left of the circle of faint stars that forms Pisces’ western fish. The planet can be seen in a backyard telescope, but not while the moon is so bright – so wait until the end of this week to look for the planet. Use binoculars to find the upright, tilted rectangle formed by the medium-bright stars 27, 29, 30, and 33 Piscium. Neptune will be the bluish, dull “star” sitting about two finger widths to the upper right (or 2° to the celestial north) of that box. Neptune will look best in a telescope when it will be higher in the sky, before 10 pm.

This month, the distant ice giant planet Uranus will be observable any time after dusk. It is located in the eastern early evening sky about a palm’s width to the right (or celestial southwest) of the bright little Pleiades star cluster in Taurus (the Bull). If you use your binoculars to find the medium-bright stars named Botein and Epsilon Arietis, Uranus will be the dull-looking blue-green “star” located several finger widths below (or southeast of) them. To get you in the vicinity of Uranus, look for the bright star Menkar shining 2.2 fist diameters off to the right of the Pleiades and down a little. Uranus will be a quarter of the way along the line joining the bottom star of the Pleiades to Menkar. In late evening, Uranus will be below the Pleiades in the southwestern sky.

Jupiter recently experienced opposition for 2024, so the planet is still extremely bright in the lower part of the eastern sky after dusk. From now until early February, Jupiter will be moving celestially west between the upper horn star of Taurus (the Bull), named Elnath, and Taurus’ brightest star, reddish Aldebaran, which marks the eye of the critter. This week, Jupiter and Aldebaran will be a palm’s width apart, and closing. The winter constellations will be arrayed below Jupiter every day from late evening onward. They will rotate to the planet’s left from late evening onward.

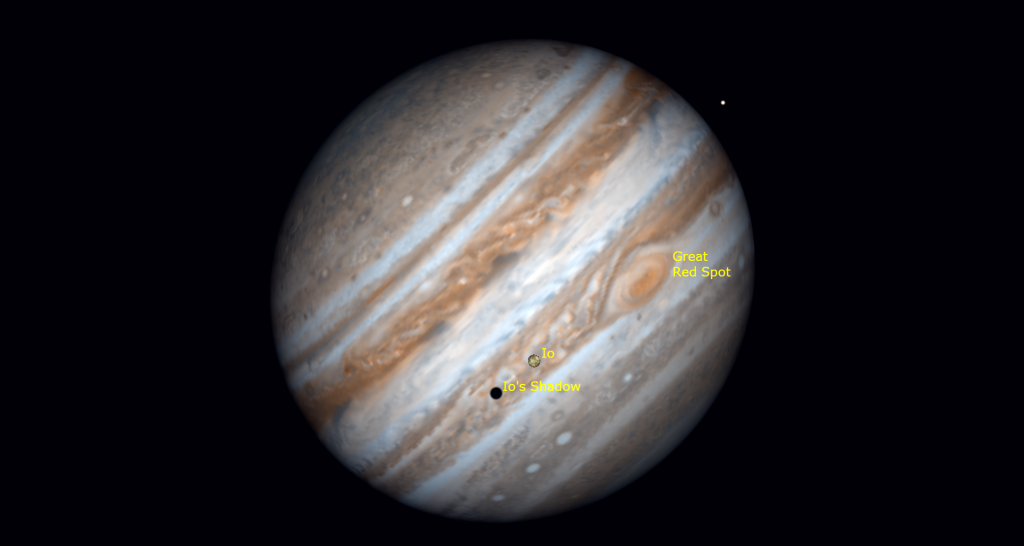

Viewed in any size of telescope, the planet will display a disk striped with brown dark belts and creamy light zones, which are aligned parallel to its equator. With a better grade of optics, Jupiter’s Great Red Spot, a cyclonic storm that has raged for hundreds of years, becomes visible for several hours when it crosses the planet every 2nd or 3rd night. For observers in the Americas, that GRS will cross Jupiter’s disk during early evening on Sunday, Tuesday, Friday, and next Sunday, and also towards midnight Eastern time on Monday and Saturday night. If you have any coloured filters or nebula filters for your telescope, try enhancing the spot with them.

Any size of binoculars will show you Jupiter’s four Galilean moons named Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto lined up beside the planet. Those moons complete orbits of the planet every 1.7, 3.6, 7.2, and 16.7 days, respectively. If you see fewer than four moons, then one or more of them is crossing in front of or behind Jupiter, or hiding in Jupiter’s dark shadow – or two of the moons are very close together, or one moon is eclipsing or occulting another one. All four moons will gather to one side tonight (Sunday).

From time to time, observers with good quality telescopes can watch the black shadows of the Galilean moons travel across Jupiter’s disk. In the Americas, Io and its little shadow will cross with the red spot following them on Monday morning, December 16 between 12:53 am and 3:03 am EST (or 05:53 to 08:03 GMT on Tuesday). Ganymede and its large shadow will cross Jupiter’s southern latitudes on Sunday, December 15 between 9:41 pm and 11:45 pm EST (or 02:41 to 04:45 GMT on Monday). Io and its little shadow will follow the great red spot across Jupiter on Tuesday, December 17 between 7:22 pm and 9:32 pm EST (or 00:22 to 02:32 GMT on Wednesday).

Mars is starting to really ramp up in brightness and colour ahead of its biggest night on January 15-16! Its prominent reddish dot will clear the trees in the east after about 9 pm local time. It will cross the sky all night long with Jupiter and Uranus, and end up halfway up the southwestern sky before dawn. In a telescope, the planet will display a small, rusty-coloured disk interrupted by some darker markings. The surface details will sharpen while Mars gets closer to Earth every day until its opposition night on January 15-16. This week we’re about 107 million km apart.

Mars will be shining in central Cancer (the Crab) and about 1.3 fist diameters below the bright star Pollux, the lower of the “twin” stars of Gemini. Mars has started a westerly retrograde loop that will last through its mid-January opposition and into late February. This week, the planet will be shining two fingers above (or celestial north of) the large open star cluster in Cancer known as the Beehive, Praesepe, and Messier 44. Mars and the stellar “bees”, which will be scattered across an area more than twice the size of a full moon, will fit into the field of view in binoculars through this week, though Mars will move increasingly farther above the cluster every night.

Public Astronomy-Themed Events

Every Monday evening, York University’s Allan I. Carswell Observatory runs an online star party – broadcasting views from four telescopes/cameras, answering viewer questions, and taking requests! Details are here. They host in-person viewing on the first clear Wednesday night each month. Other Wednesdays they stream views online via the observatory YouTube channel. Details are here.

Keep your eyes on the skies! I love getting questions and requests. Send me some!