Hanukkah Happens with Christmas Stars, Jupiter is Spotted, and the Old Morning Moon Poses Prettily!

Merry Christmas to those who celebrate! This wonderful object, known as the Christmas Tree Cluster or NGC 2264, is located in the constellation of Monoceros (the Unicorn), which occupies the winter sky between Orion and Gemini. The red glows are hydrogen gas being energized by the clump of hot, young stars recently born in the centre. Blues arise from starlight reflecting off surrounding dust, and the dark patches are more dust that is obscuring light behind it. The image by Rolf Geissinger of southern Germany, was NASA’s Astronomy Picture of the Day for April 10, 2012. It spans about one finger’s width of the sky.

Merry Christmas and Happy Hanukkah, Stargazers!

Here are your Astronomy Skylights for the week of December 22nd, 2024 by Chris Vaughan. Feel free to pass this along to your friends and send me your comments, questions, and suggested topics. You can also follow me on Twitter as @astrogeoguy! Unless otherwise noted, all times are expressed in Eastern Time. To subscribe to these emails please click this MailChimp link.

If you’d like me to bring my Digital Starlab portable inflatable planetarium to your school or other daytime or evening event in Simcoe, Grey, and Bruce Counties, or deliver a virtual session anywhere, contact me through AstroGeo.ca, and we’ll tour the Universe, or the Earth’s interior, together! My book with John A. Read entitled 110 Things to See With a Telescope is a guide to viewing the deep sky objects in the Messier List – for both beginners and seasoned astronomers. DM me to order a signed copy!

With everyone taking some time off for the Holidays, I’m sharing lots to read about Hanukkah and Kwanzaa, and Christmas-themed stars you can see for yourself on the next starry night. This will also be a prime week for viewing the planets at their best – most of them in the evening and Mercury in the morning. We end the week with a meet-up of the gorgeous crescent moon, Antares, and Mercury. Read on for your Skylights!

Hanukkah and the Jewish Calendar

Astronomy is a secular science, but there is plenty of astronomy embedded within religious and cultural traditions whose adherents have gazed upon the heavens since antiquity. Let’s look at Hanukkah (or Chanukah, meaning “dedication/consecration/housewarming”, which begins at sundown on Wednesday, December 25 this year.

Most cultures around the world have designed their calendars around the cycles of the moon and the sun’s altering position in the daytime sky and its apparent passage through the stars. The Jewish lunisolar calendar (and others) uses the first glimpse of the young, crescent moon to mark the beginning of a month. But the moon’s phases repeat every 29.5 days, so that missing half-day needs to be factored in. The Jewish calendar makes some months only 29 days in length – the chaser “missing” months – and other months 30 days in length – the malei, “full” months.

To account for the ten-day difference between the length of the solar year and twelve 29.5-day lunar months, and to ensure that the calendar of Jewish observances remains synchronized with the seasons, a leap-month is added every two or three years on a repeating 19-year Metonic cycle. On those years, the springtime month of Adar is observed twice consecutively.

Nissan, the first month in the Jewish calendar, begins with the new moon following the March Equinox. But the Jewish New Year, which is said to honour the anniversary of the creation of Adam and Eve, occurs on the first day of the seventh month, which is named Tishrei. That month always falls in September-October on our western Gregorian calendar.

The month of Tishrei hosts the Jewish High Holidays – Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur, plus the significant days of Sukkot, Shimini Atzeret, and Simchas Torah. Rosh Hashanah, which marks Jewish New Year, falls on Tishrei 1. Yom Kippur “day of atonement” falls on the tenth day of the seventh month.

Hanukkah, or the Festival of Lights, is observed for eight nights and days, starting at sunset on the 25th day of the Hebrew month Kislev, which may occur at any time from late November to late December in the Gregorian calendar. The last new moon was on December 1, so Hanukkah will commence on Wednesday, December 25 and end at sundown on Thursday, January 2.

This year’s High Holidays and Hanukkah haven’t been this late since 2005, but the leap-month of Adar II that was added in spring, 2024 will re-aligned them for next year. Hanukkah falls on Christmas about every 15 years.

The Jewish, Christian, and Muslim calendars all share similar roots, which is why Passover and Easter, and Christmas and Hanukkah, are often coincident. The Muslim calendar is allowed to drift due to the ten-day lunar month to solar year difference, but it resets every 33 years. The Muslim New Year occurs at the Vernal Equinox – but that’s a story for another time.

The timing of Kwanzaa, the annual celebration of African-American culture observed from December 26 to January 1, is not affected by the moon or sun. First celebrated in 1966, it was adopted from the First Fruits festivals of the Nguni peoples in Southern Africa. That celebration was observed around the December solstice.

A Christmas Constellation – Rangifer (the Reindeer)!

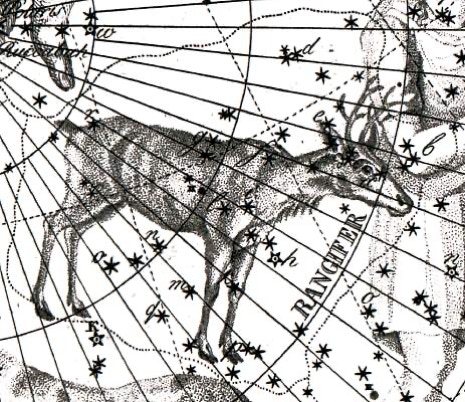

According to astronomer Ian Ridpath, French astronomer Pierre-Charles Le Monnier (1715–99), in a star chart published in his 1743 book La Théorie des Comètes, created a faint, far-northern constellation close to the north celestial pole between Cepheus (the King) and Camelopardalis (the Giraffe). When illustrating the track of the Comet of 1742 through the north polar region of the sky, Le Monnier envisioned a reindeer on the comet’s course!

Labelled in various old charts as Rangifer and as Tarandus, he connected up some of the modest, magnitude 4 and 5 stars sitting between the “W” of Cassiopeia and Polaris. You have probably not heard of this star pattern because it is not one of the IAU’s official 88 constellations. Ian’s story about the reindeer is here. I think I’ll have to look for the critter on the next clear night!

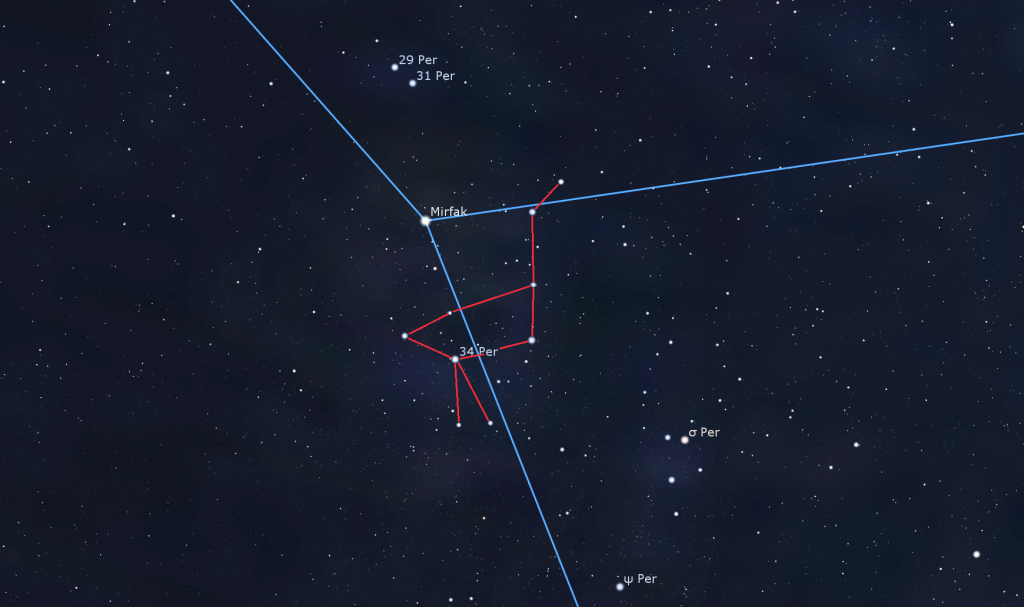

The Christmas Goose

The brightest star in Perseus (the Hero) is Mirfak or Alpha Persei (α Per). On the evenings surrounding Christmas every year, Perseus can be found climbing the east-northeastern sky above the very bright star Capella (and Jupiter in 2024) and below the W-shaped stars of Cassiopeia (the Queen). Grab your binoculars! Mirfak’s pale golden gem sparkles at the upper left (northwestern) edge of a large and loosely scattered cluster of about 100 hot, bright, blue-white B and A-class stars known as the Alpha Persei Moving Group, the Perseus OB Association, and Melotte 20. Those stars are siblings of Mirfak – born from the same molecular hydrogen cloud about 41 million years ago – and now travelling through the galaxy together with Mirfak. The open star cluster, which is sprinkled across 3 degrees of the sky, can be seen with unaided eyes, and looks wonderful in binoculars. In his book Binoculars Highlights, astronomer Gary Seronik suggested that the brightest stars in Mirfak’s cluster resemble a goose.

Christmas Star Candidates?

Sirius, the brightest star in Canis Major (the Big Dog) and the brightest star in the night sky worldwide, will be shining in low the southeastern sky after about 8:30 pm local time this week. Sirius is hard to miss once it clears the trees and rooftops. If you are walking through your darkened house in the middle of the night, the star might catch your eye out a window because it never climbs very high. It will culminate in the lower part of the southern sky at about 1 am local time this week. (Those times are 4 minutes earlier per day due to Earth’s orbital motion around the sun.)

Sirius is a hot, blue-white, A-class star located a mere 8.6 light-years away from our sun. Its extreme brightness and low elevation in the sky from mid-northern latitudes combine to produce spectacular flashes of color as it twinkles. A very large telescope may allow you to see Sirius B, a faint white dwarf companion star located just 10 arc-seconds east of Sirius. (Remember to account for how your telescope flips the scene.)

Cold Weather Astronomy Tip: If you plan to use your telescope on winter evenings, set it outside in a safe location (even an unheated garage or car trunk will do) for at least a couple of hours ahead of time. That will allow the air trapped inside it to chill down to ambient, reducing the turbulent “tube currents” that distort the images. Leave all the lens caps in place until viewing time to prevent frosting on the glass elements. And put those caps back on before bringing it back inside at the end of the session. Better yet, zip it into its case or snug a plastic bag around it while still outside. That way, the moisture in the warm house air cannot condense on it. Open it up to air out after it has warmed up.

With Venus continuing to gleam in the southwestern sky after sunset until mid-March, it’s easy to imagine that sky-watchers of old could be captivated by Venus’ brilliance and declare it the “Christmas Star” while it was shining in the east before dawn. Venus puts on those celestial showings, in the east before sunrise or in the west after sunset, every 1.6 years – hardly a rare occurrence.

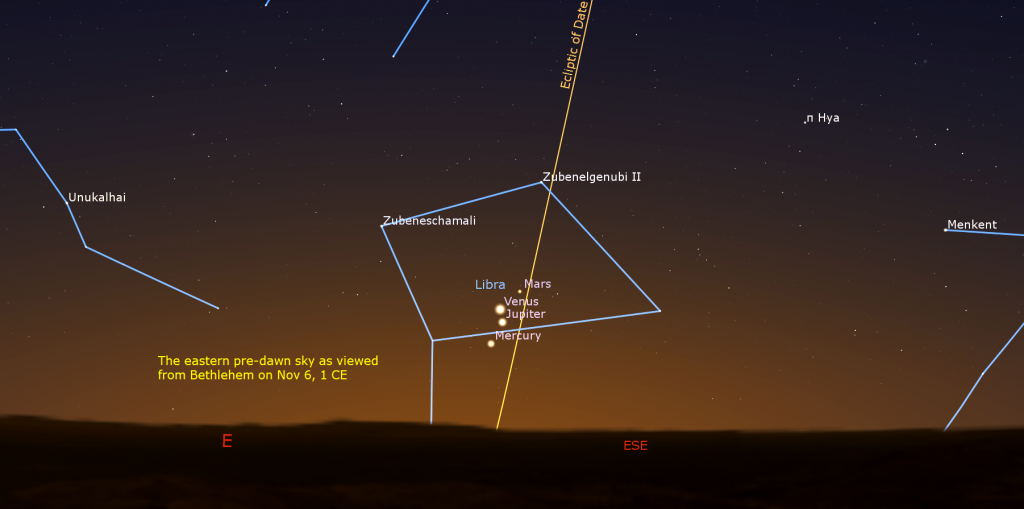

The event that may have spawned the biblical story of wise men following a star in the east, was a rare planetary conjunction of Mercury, Jupiter, Mars, and Venus that occurred in the eastern pre-dawn sky in early November of the year 1 CE. In fact, on one of those mornings, Venus and Jupiter were so close together that they might have looked like a single, extra-bright object! For about a week, all four bright planets were grouped into a stubby line that spanned less than four fingers widths in length. The spectacle was visible from nearly everywhere on Earth. The next time you see bright Venus, imagine how impressive those other planets gathered around her would have looked.

Alternate explanations for the Christmas star include a bright supernova or a passing comet. Both would be memorable, rare, and temporary, but we have not yet found a supernova remnant that matches the required location in the sky, and surely a bright comet’s tail would have been mentioned by the observers!

The Moon

The moon will spend this week swinging toward the sun in the morning sky and waning in illuminated phase. That will deliver increasingly darker evening skies worldwide for stargazers.

The moon will reach its third quarter (or last quarter) phase, i.e., completing three quarters of its orbit around Earth, measuring from the previous new moon, today (Sunday, December 22) at 5:18 pm EST, 2:18 pm PST, or 22:18 Greenwich Mean Time. The moon’s phases occur independently of Earth’s rotation. We won’t see the moon’s half-illuminated disk until it rises with the stars of Virgo (the Maiden) around midnight. At this part of the moon’s monthly cycle, it doesn’t set until mid-day – so you are likely to catch sight of the moon in daylight on your way to school or work.

Folks that get outside early will enjoy the pretty waning crescent moon in the southeastern sky. It will travel through Virgo until Wednesday morning. The bright star sparkling near it on Tuesday morning will be Spica, Virgo’s brightest. The moon will spend Thursday and Friday in Libra (the Scales).

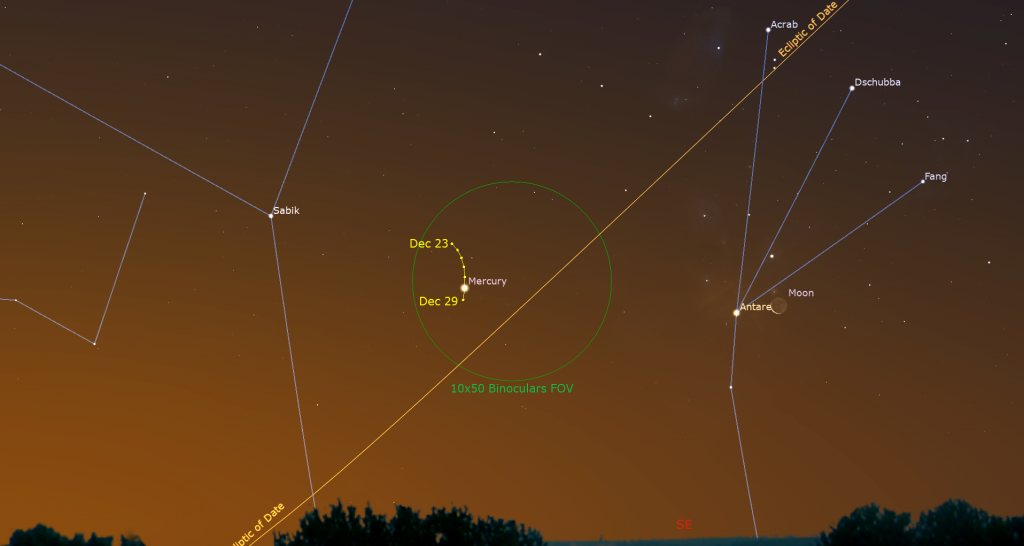

If the weather forecast calls for clear skies to the southeast on Saturday morning, it will be worth venturing outside around breakfast time to see the pretty spectacle of the old, waning moon’s slender crescent shining close to Scorpius’ brightest star Antares “the Rival of Mars” and brighter Mercury nearby. All three objects will clear the treetops by about 7 am local time.

Reddish Antares will be twinkling just to the moon’s lower left (or celestial southwest). They’ll be extra close together for observers in westerly time zones. The moon will actually pass in front of, or occult, Antares – but that event will only be observable in a part of the Pacific Ocean’s vast empty expanse.

Meanwhile, Mercury’s bright dot will be positioned nearly a fist’s diameter to the left (or 9 degrees to the celestial northeast) of Antares. The very old crescent moon should also display Earthshine, also known as the Ashen Glow and “the old moon in the new moon’s arms”. The phenomenon, sunlight reflected off Earth and back onto the moon, slightly brightening the dark portion of the moon’s Earth-facing hemisphere, appears for several days before and after each new moon.

Next Sunday morning’s 2.3%-illuminated sliver of a moon won’t really be visible before sunrise unless you live near the tropics.

The Planets

This will be a terrific week to see all the planets under excellent circumstances!

The speedy planet Mercury should be easy to see while it shines at a bright magnitude -0.4 above the southeastern horizon before sunrise all week. At mid-northern latitudes the planet will rise around 6 am local time. Scorpius’ bright star Antares will sparkle a palm’s width to the planet’s lower right (or 6 degrees to the celestial SSW). In a telescope Mercury will exhibit a 64%-illuminated, waxing gibbous phase that will be “swimming” due to the extra air we are looking at it through. But you should still be able to make out its half-moon shape. Turn optics away from the horizon before the sun starts to rise.

On Wednesday morning, Mercury will reach its widest angle of 22° west of the sun, and peak visibility, for its current morning apparition. Astronomers call that phenomenon a planet’s greatest elongation. The planet will continue to be well-placed for viewing for about two more weeks. Don’t forget to check out the pretty crescent moon nearby on Saturday.

Venus is the brilliant “Evening Star” you will see gleaming in the southwestern sky every evening. The planet will be visible even before the sky darkens, but if the bright object you see is moving left or right, or flashing, that’s an airplane! The stars of Capricornus (the Sea-Goat) that are hosting Venus will appear after the sky darkens. Venus’ orbital motion is still carrying it away from the sun, and in the direction of Saturn. They’ll “kiss” in a close conjunction in mid-January. This week, Venus will be setting at about 8:30 pm local time and Saturn will be about 2.2 fist diameters to its upper left (or celestial east). When viewed through a telescope or very strong binoculars, Venus will show a waning, barely gibbous phase.

Before Venus disappears into the trees to the west, you can turn around and find bright reddish Mars rising in the eastern sky. All of the other planets except morning Mercury will be strung like beads along the ecliptic between Mars and Venus.

Saturn will set next after Venus – at about 10:30 pm local time. You’ll have clear views of the planet in any backyard telescope only until about 9:30 pm. Since it’s much less bright than Venus, you’ll need the sky to darken a bit more before you can see Saturn’s yellowish dot in the lower part of the southwestern sky. Use the two fist diameters separation from Venus to guide you. The prominent star Fomalhaut in the constellation of Piscis Austrinus (the Southern Fish) twinkling about two fist diameters below, and a little to the right, of Saturn, will be almost as bright. The faintish stars of Aquarius (the Water-Bearer) that are hosting Saturn will show up once the sky fully darkens.

Saturn’s bright, but extremely thin rings effectively disappear when they become edge-on to Earth every 15 years. Since we are only three months away from that event, in late March, 2025, the rings already appear as a thick line drawn through the planet. Any size of telescope will show the rings and some of Saturn’s larger moons, too. In most years, Saturn’s moons are sprinkled around the planet, unlike Jupiter’s Galileans moons, which are always in a line. But while Earth is within months of being aligned with Saturn’s ring plane, its moons don’t stray very far from the ring plane.

Saturn’s largest and brightest moon Titan “TIE-tan” never wanders more than five times the width of Saturn’s rings from the planet. The much fainter moon named Iapetus “eye-YA-pet-us” can stray up to twelve times the ring width during its 80-day orbit of Saturn. The next brightest moons Rhea “REE-ya”, Dione “Dee-OWN-ee”, Tethys “Teth-EES”, Enceladus “En-SELL-a-dus”, and Mimas “MY-mass” all stay within one ring-width of Saturn. You may be surprised at how many of those six you can see through your telescope if you look closely when the sky is clear, dark, and calm.

During early evening this week, Titan will start from a position just to Saturn’s lower right (or celestial west) tonight (Sunday). It will swing well to the planet’s right on Thursday and then planetward next Sunday. (Remember that your telescope will probably flip the view around.) The rest of the moons will be tiny specks in a line near the rings. Earth’s perspective of the Saturn system will also cause Saturn’s moons and their small black shadows to frequently cross its disk – but you’ll need a very high quality telescope to watch those.

The distant and dim, blue planet Neptune is following Saturn about an hour behind it on the ecliptic. That places Neptune 1.3 fist widths to Saturn’s upper left (or celestial ENE) and a palm’s width to the lower left of the circle of faint stars that forms Pisces’ western fish. Neptune will be visible in a backyard telescope this week and next while the moon is absent. Use binoculars to find the upright, tilted rectangle formed by the medium-bright stars 27, 29, 30, and 33 Piscium. Neptune will be the bluish, dull “star” sitting about two finger widths to the upper right (or 2° to the celestial north) of that box. Neptune will look best in a telescope when it will be higher in the sky, before 10 pm.

The next planet along the string – Uranus – is five hours behind Neptune. So you have plenty of dark, moonless hours to view it this week. This month, the distant ice giant planet will be observable any time after dusk. It is located in the eastern early evening sky about a palm’s width to the right (or celestial southwest) of the bright little Pleiades star cluster in Taurus (the Bull). If you use your binoculars to find the medium-bright stars named Botein and Epsilon Arietis, Uranus will be the dull-looking blue-green “star” located several finger widths below (or southeast of) them. To get you in the vicinity of Uranus, look for the bright star Menkar shining 2.2 fist diameters off to the right of the Pleiades and down a little. Uranus will be a quarter of the way along the line joining the bottom star of the Pleiades to Menkar. In late evening, Uranus will be below the Pleiades in the southwestern sky.

Next in line, nearly two hours behind Uranus on the ecliptic, is Jupiter. The giant, white planet will catch your eye in the lower part of the eastern sky after dusk – around the same time that Venus appears in the west. From now until early February, Jupiter will be creeping west towards the stars that form the triangular face of Taurus (the Bull) and Taurus’ brightest star, reddish Aldebaran, which marks the eye of the beast at the lower corner of the triangle. This week, Jupiter and Aldebaran will be a palm’s width apart. The winter constellations will rise below Jupiter every evening. By the time the clock strikes midnight, those constellations will have rotated to the planet’s left.

Viewed in any size of telescope, Jupiter will display a substantial disk striped with brown dark belts and creamy light zones, both aligned parallel to its equator. With a better grade of optics, Jupiter’s Great Red Spot, a cyclonic storm that has raged for hundreds of years, becomes visible for several hours when it crosses the planet every 2nd or 3rd night. For observers in the Americas, that GRS will cross Jupiter’s disk during early evening on Sunday, Tuesday, Thursday, and next Sunday, and also towards midnight Eastern time on Monday, Thursday, and Saturday night. If you have any coloured filters or nebula filters for your telescope, try enhancing the spot with them.

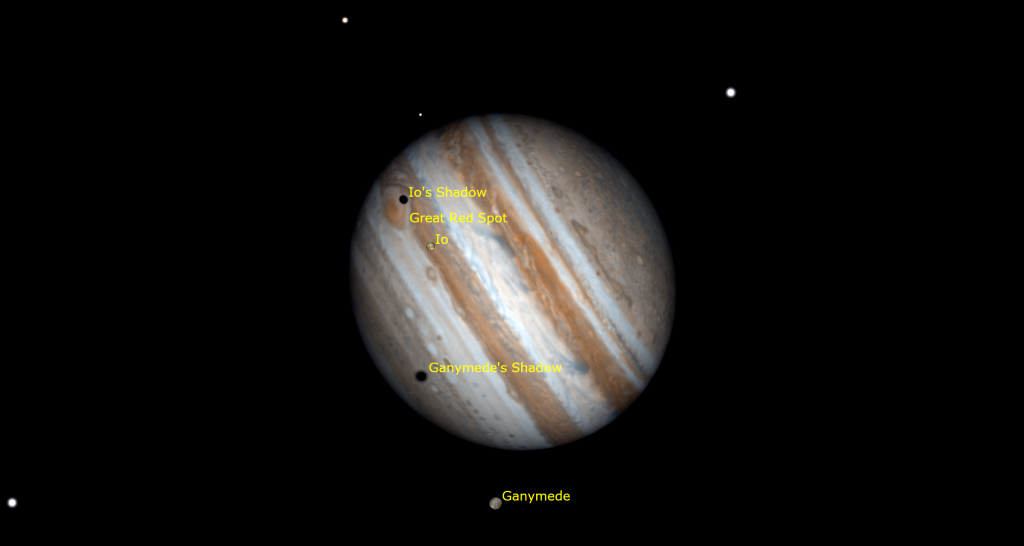

Any size of binoculars will show you Jupiter’s four Galilean moons named Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto lined up beside the planet. Those moons complete orbits of the planet every 1.7, 3.6, 7.2, and 16.7 days, respectively. If you see fewer than four moons, then one or more of them is crossing in front of or behind Jupiter, or hiding in Jupiter’s dark shadow – or two of the moons are very close together, or one moon is eclipsing or occulting another one. All four moons will gather to one side on Monday and next Sunday.

From time to time, observers with good quality telescopes can watch the black shadows of the Galilean moons travel across Jupiter’s disk. On Monday morning, December 23, sky-watchers located in the Americas can watch the rare event of two of the shadows and the Great Red Spot crossing the southern hemisphere of Jupiter together for about an hour. At 2:48 am Eastern Time (or 07:48 GMT), the red spot and the small shadow of Io will join the much larger shadow of Ganymede, which began its own crossing of the planet’s south polar zone 70 minutes earlier. Ganymede’s shadow will leave Jupiter at 3:48 am EST (or 08:48 GMT), leaving Io’s shadow and the spot to continue on alone until 4:58 am EST. Watch for Io itself to move off of Jupiter’s disk by 4:35 am EST.

A more conveniently timed shadow transit will be visible in the Americas when Io and its little shadow cross Jupiter on Tuesday, December 24 between 9:18 pm and 11:26 pm EST (or 02:18 to 04:26 GMT on Wednesday).

Mars is starting to really ramp up in brightness and colour! Its prominent reddish dot will clear the trees in the east after about 8 pm local time. It will cross the sky all night long behind Jupiter and Uranus, and end up descending the western sky before dawn. In a telescope, the planet will display a small, rusty-coloured disk and some darker markings. The surface details will sharpen while Mars gets closer to Earth every day until its opposition night on January 15-16. This week we’re about 101 million km apart.

Mars will continue to sit in central Cancer (the Crab) and about a fist diameter below the bright star Pollux, the lower of the “twin” stars of Gemini. Mars has started a westerly retrograde loop that will last through its mid-January opposition and into late February. This week, the planet will be shining several finger widths above (or celestial northwest of) the large open star cluster in Cancer known as the Beehive, Praesepe, and Messier 44. Mars and the stellar “bees”, which will be scattered across an area more than twice the size of a full moon, will just fit into the field of view in binoculars until about Friday.

Public Astronomy-Themed Events

Every Monday evening, York University’s Allan I. Carswell Observatory runs an online star party – broadcasting views from four telescopes/cameras, answering viewer questions, and taking requests! Details are here. They host in-person viewing on the first clear Wednesday night each month. Other Wednesdays they stream views online via the observatory YouTube channel. Details are here.

Keep your eyes on the skies! I love getting questions and requests. Send me some!