A Bright Beaver Moon Mangles Meteors, Tiny Mercury Transits the Sun, and Vesta Veers Closer!

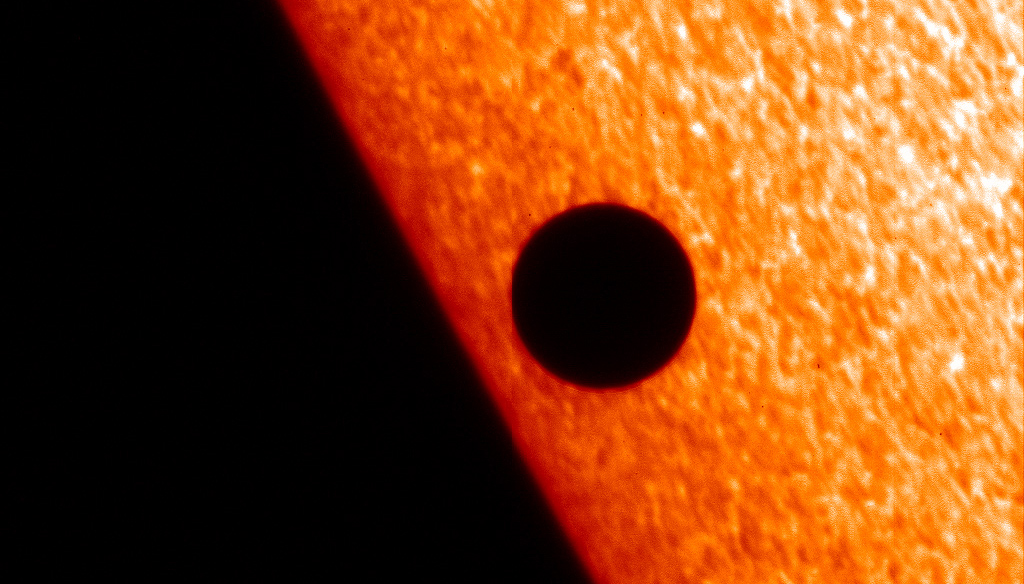

This image of Mercury transiting the sun on November 8, 2006 was taken using a Hydrogen-alpha telescope. To see tiny Mercury on the sun during the 5.5 hour event, a properly solar filtered telescope will be required. Or watch the event online, if you get cloudy skies!

Hello, November Stargazers!

Here are your Astronomy Skylights for the week of November 10th, 2019 by Chris Vaughan. Feel free to pass this along to your friends and send me your comments, questions, and suggested topics. I repost these emails with photos at http://astrogeo.ca/skylights/ where all the old editions will be archived. You can also follow me on Twitter as @astrogeoguy! Unless otherwise noted, all times are Eastern Time. To subscribe to these emails please click this MailChimp link.

I can bring my Digital Starlab portable inflatable planetarium to your school or other daytime or evening event. Contact me through AstroGeo.ca, and we’ll tour the Universe together!

Two more modest meteor showers will peak this week – but the bright, Full Beaver Moon’s moonlight will spoil our fun. To compensate us, on Monday observers with solar filtered telescopes and sunny skies will get to see a rare crossing of the disk of the sun by Mercury. Meanwhile, the large asteroid Vesta will be closest to Earth – and Earth’s nearest planets, Venus and Mars, will continue to improve in visibility as they increase their distances from the evening and morning sun, respectively. Here are your Skylights!

Northern Taurids and Leonids Meteor Showers Peak

The annual Northern Taurids Meteor shower delivers meteors to observers worldwide from October 19th to December 10th annually. It will peak overnight on Monday-Tuesday this week. The long-lasting, weak shower is derived from debris dropped by the passage of a periodic comet named 2P/Encke, the second such comet to be discovered, in 1786. (Periodic comets such as 1P/Halley and 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko orbit in our solar system on a regular schedule, never venturing too close to the sun to be disintegrated.)

Like last week’s related Southern Taurids shower, this one’s cometary debris’ larger than average grain size often produce colorful fireballs. The peak of activity, when up to five meteors per hour are predicted, will occur at about 12 am EST (or 05:00 Greenwich Mean Time). At that time, Earth will be traversing the densest part of the comet’s debris train. The full moon near Taurus on the peak night will overwhelm most of the meteors.

The annual Leonids Meteor shower, derived from material left by repeated passages of periodic Comet 55P/Tempel-Tuttle, runs from November 5th to December 3rd. At the peak, before dawn on Sunday, November 17, expect to see about 15 meteors per hour, many with persistent trains. The bright, waning gibbous moon on the peak night will brighten the sky, washing out many of these meteors, too.

Both of these showers are worldwide events. You can start watching for meteors as soon as it’s dark. The best viewing time will occur on the peak night in the hours after midnight local time, when the shower’s radiant will be highest in the sky. (When a shower’s radiant is low in the sky, the local horizon hides many of the meteors.) I wouldn’t make a special trip to see meteors with so much moonlight – but keep an eye out for them if you are already outside on a clear night.

The Transit of Mercury

On November 11, 2019, the world will witness a rare transit of Mercury across the disk of the sun. You’ll need a telescope equipped with a proper solar filter to view the five-hour event – but whether you can see it at all depends on where you live.

Mercury orbits the sun every 88 days. From our vantage point here on Earth, the speedy planet passes the sun twice in every orbit – once when it’s between us and the sun, and once when it’s on the far side of the sun. These events are called solar conjunctions, and all planets experience them. But only Venus and Mercury can produce solar inferior conjunctions – when they pass between us and the sun.

Mercury’s orbit is tilted by 7 degrees with respect to Earth’s orbit – which we draw on the sky as the Ecliptic. The two points in space where Mercury’s orbit crosses the ecliptic are called nodes. Most of the time, when Mercury passes the sun at inferior conjunction, it misses the sun by several degrees. But if the sun is near either of the two nodes, Mercury can cross, or transit the disk of the sun – as seen from our vantage point on earth.

Solar eclipses by the moon work by the same principle; as a matter of fact, a Mercury transit is actually a partial solar eclipse, since it hides a tiny bit of the sun. But while the moon’s disk is large enough to cover the sun quite frequently, the tiny disks of Mercury (and Venus) require a much more precise alignment for a transit – and so the transits are rare.

Transits of Mercury always occur in early May or mid-November, and are more common than transits by Venus. There are typically about 13 or 14 Mercury transits per century. The last transit was on May 9, 2019. The next one after Monday will occur on November 13, 2032 – so it’s worth trying to see this one!

Transits of planets have stages. First contact is defined as the moment that the edge of the planet first touches the edge of the sun. Second contact occurs when the planet is first completely within the sun’s disk – usually about 90 seconds after first contact. This is a terrific part of the transit to watch through a safely filtered telescope.

If the geometry of the encounter has Mercury crossing near the center of the sun, the transit time will be five or six hours. It will be extremely short if the planet crosses close to the northern or southern pole of the sun – and of intermediate duration between those two extreme cases.

The final stages of the transit are third contact, when the planet is about to move off the opposite side of the sun’s disk, and fourth, or last, contact – the last moment when the planet’s edge is touching the sun’s edge. This stage, too, is very brief, and is exciting to view close-up.

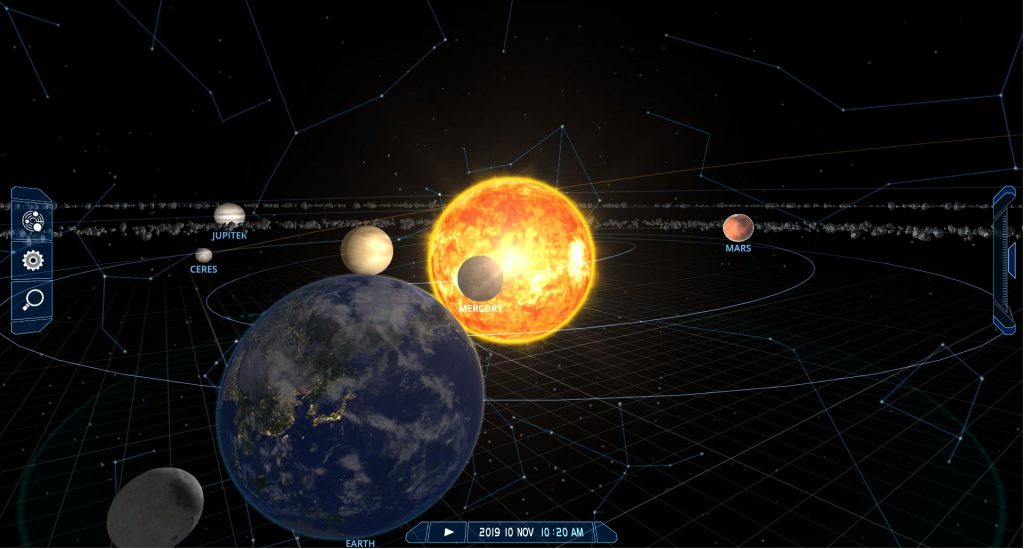

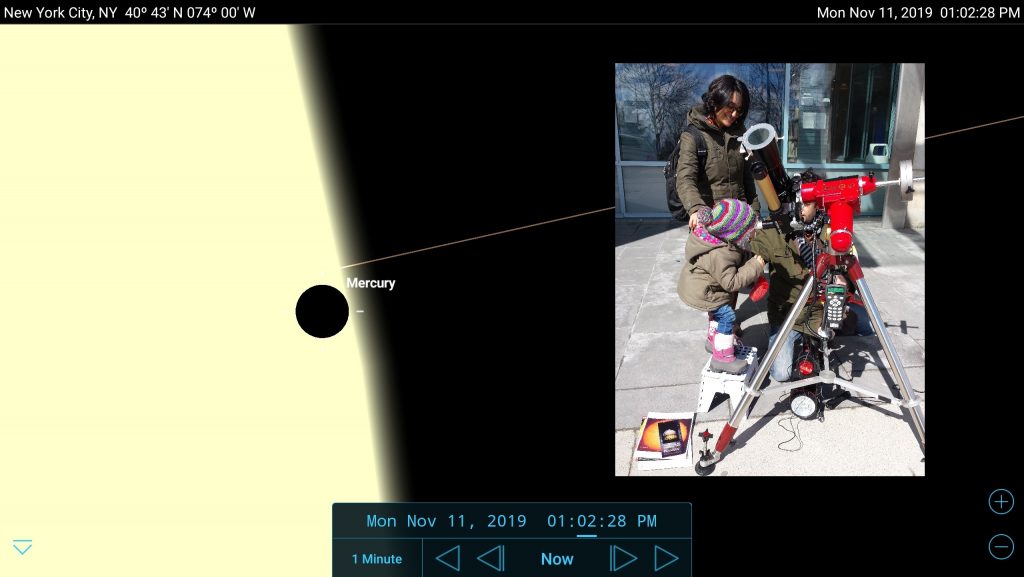

Let’s review the details of Monday’s transit and show you how to preview it on your favorite astronomy app – or to follow along if you don’t own a solar-filtered telescope, or live where it’s visible.

Monday’s transit of Mercury will be visible from all of North America, but only the eastern portion of the continent will see the first and second contacts with the sun. The Eastern seaboard, the Caribbean, Central and South America, and the western edge of equatorial Africa will see the entire event from start to finish.

For the rest of North America and the Pacific Ocean region, Mercury will already be crossing the sun at sunrise. For Europe, the Middle East, and the rest of Africa, the sun will set before Mercury has completed its journey. Asia and Oceania will not see any of the Eclipse. Eclipsewise.com, which is an excellent resource for solar and lunar events, has a good map here that shows the zones of visibility.

First contact will occur at 7:35:27 am Eastern standard Time (12:35:27 GMT), and last contact will occur at 1:04:14 pm EST (18:04:14 GMT). For locations in North America, the sun will be low in the southeastern sky at mid-transit around 10:20 am EST.

Mercury’s tiny disk will not be visible through eclipse glasses or filtered binoculars. You’ll need a properly filtered telescope or a dedicated solar telescope. Any size will do – but be sure to affix proper solar filters BEFORE aiming your telescope anywhere near the sun!

Check with your local astronomy organizations and universities for details about any public viewing parties they have planned. Wishing you sunny skies! If Monday is cloudy, watch Gianluci Masi’s live observing session of the transit from the Virtual Observatory, starting at 7:30 am EST (12:30 GMT).

The Moon and Planets

The moon will dominate the evening and late-night skies worldwide this week. Starting from its position among the dim stars of Pisces tonight (Sunday), the moon will slide through the southern edge of Aries (the Ram) on Monday night.

On Tuesday morning at 8:35 am EST, the full moon of November, traditionally called the Beaver Moon or Frost Moon, will occur. At a casual glance, the moon will appear full on both Monday night and Tuesday night; but a magnified view will reveal craters in shadow along the eastern edge on Monday and along the western edge on Tuesday, when the moon has crossed the Earth-sun line. The brightness variations on the full moon are only due to geological and texture differences. And fully illuminated moons best show the rays of ejecta blasted out of the large, recent craters.

Indigenous groups have their own names for the full moons, which lit the way of the hunter or traveler at night before modern conveniences like flashlights. The Ojibwe of the Great Lakes region call this one Mnidoons Giizisoonhg, the “Little Spirit Moon”, a time of healing. The Cree of North America call it Kaskatinowipisim, the “Freeze Up Moon”, when the lakes and rivers start to freeze.

Since it’s opposite the sun on this day of the lunar month, the full moon rises at sunset and sets at sunrise. The November moon always shines in or near the stars of Taurus (the Bull) and Aries. Full moons occurring during the winter months in North America will climb as high in the sky as the summer noonday sun, and cast similar shadows.

During the middle of the week, the now-waning gibbous moon will traverse Taurus (the Bull). Look for the bull’s eye – the bright, reddish star Aldebaran – sitting just two finger widths below the moon on Wednesday night. On Friday night, the moon will tickle the toes of Gemini (the Twins). And after midnight next Sunday evening, the waning gibbous moon will approach and then pass the heart of the large, open star cluster known as the Beehive (and Messier 44) in Cancer (the Crab). I’ll write more about that in next week’s Skylights.

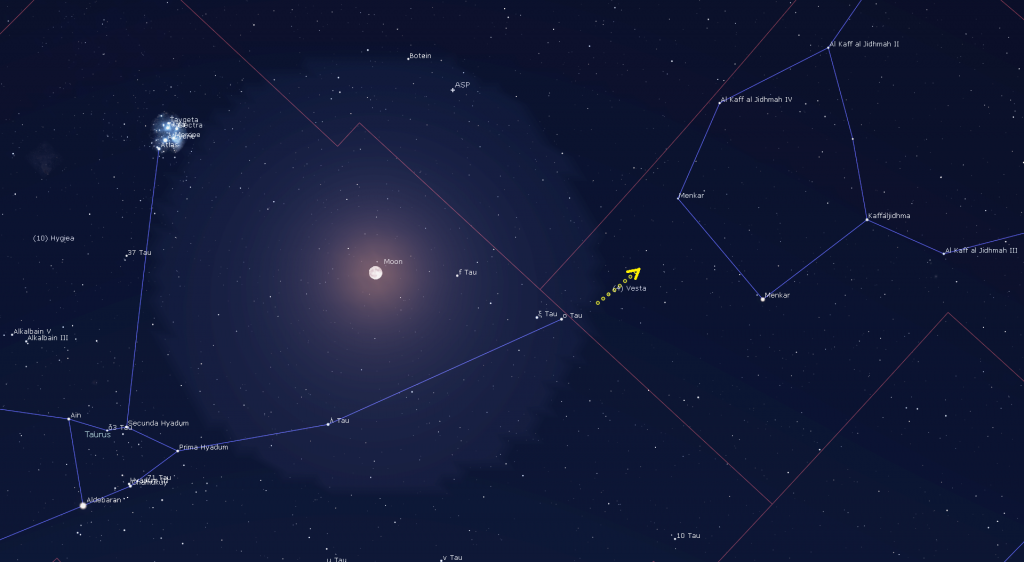

On Tuesday, November 12 Earth’s orbit will carry us between the minor planet (or asteroid) Vesta and the sun. Sitting opposite the sun in the sky, Vesta will be visible all night long, and appear at its brightest (magnitude 6.5) for the year – well within reach of binoculars and small telescopes. Look for the object in eastern Cetus (the Whale), approximately a fist’s diameter to the right of the moon. (That’s 9.5 degrees to the celestial southwest of the moon – in astronomy-lingo.) Vesta will also be located a palm’s width to the left of the star Menkar, which can guide you to Vesta after the moon has left the area.

Following its encounter with the sun on Monday, Mercury will re-appear very low in the southeastern pre-dawn sky next weekend. The best viewing time will be around 6:30 am local time. This new morning apparition will be a very good one for Northern Hemisphere observers, but poor for those viewing it from mid-southern latitudes.

Now shining at a spectacularly bright magnitude of -3.85, Venus is still being held low in the southwestern post-sunset sky by the shallow angle of the evening ecliptic. The planet is gradually ascending out of the surrounding evening twilight, and will be fairly easy to spot for a brief period after sunset this week, if you can find a low open horizon to the west-southwest. The planet will set at 6 pm local time.

Jupiter and Venus are moving in opposite directions – which will cause them to meet up spectacularly in two weeks time! Venus’ orbital motion is drawing it eastward away from the sun, while Jupiter is being carried toward the sun by Earth’s orbit.

Jupiter will be setting in the west at about 7 pm local time this week. As the sky begins to darken, look for the giant planet sitting about a fist’s diameter above the southwestern horizon. Once Jupiter disappears in a few weeks, we’ll have to wait next February, when it will gleam in the southeastern pre-dawn sky, for the new season of Jupiter-viewing to commence.

Yellow-tinted Saturn, which is rather less bright than Jupiter, is still a reasonably good option for viewing in backyard telescopes. Look for it in the south-southwestern evening sky. At dusk, it will be located about two fist diameters above the southern horizon. It will set in the west-southwest at 8:30 pm local time. All year, Saturn has been located just above (or to the celestial northeast of) the stars that form the teapot-shaped constellation of Sagittarius (the Archer), and also about 2.5 fist diameters to the upper left (or celestial east) of Jupiter.

A look at Saturn is well worth dusting off your old telescope! Once the sky is dark, even a small telescope will show Saturn’s rings and several of its brighter moons, especially Titan! Because Saturn’s axis of rotation is tipped about 27° from vertical (a bit more than Earth’s axis), we can see the top surface of its rings, and its moons can arrange themselves above, below, or to either side of the planet. During this week, Titan will migrate counter-clockwise around Saturn, moving from the lower left of Saturn tonight (Sunday) to the right of the planet next Sunday. (Remember that your telescope will flip the view around.)

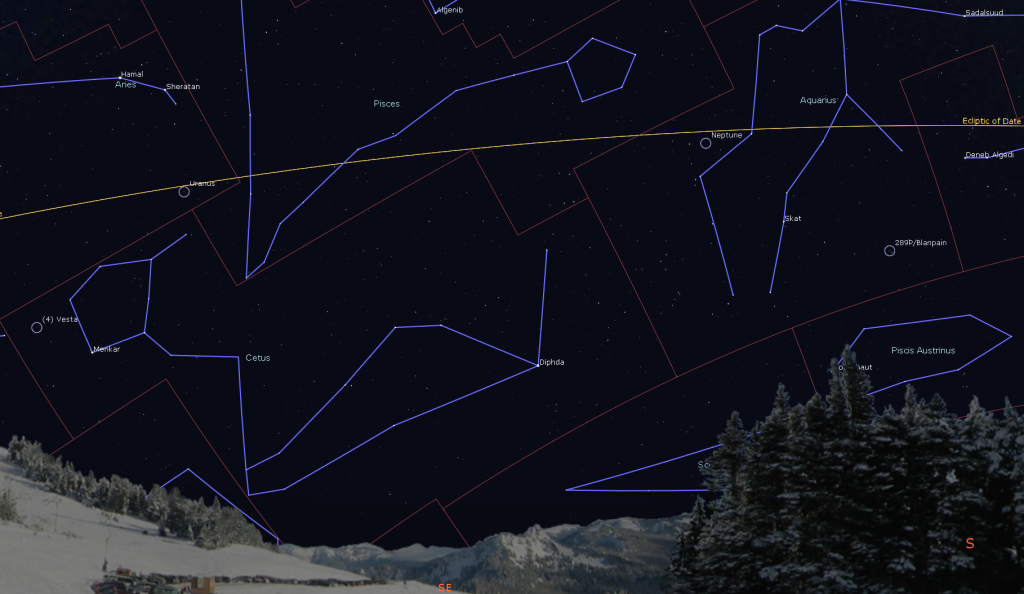

Next in line along the night-time ecliptic’s path of the planets, distant and dim, blue Neptune is visible from dusk until about 1:30 am local time. It is among the stars of eastern Aquarius (the Water-Bearer), and sits less than a finger’s width to the right (or celestial west) of a medium-bright star named Phi (φ) Aquarii. Both blue Neptune and that golden-coloured star will appear together in the field of view of a backyard telescope at low power. The distance between the star and the planet is steadily increasing due to Neptune’s westward retrograde orbital motion. I posted a diagram of Neptune’s position compared to that star here.

Blue-green Uranus is only two weeks past its closest distance from Earth for this year. Right now, Uranus is sitting a large palm’s width to the left (or to the celestial east) of the “V” of Pisces (the Fishes), below (or to the celestial south of) the stars of Aries (the Ram), and is just a palm’s width above the ring of stars that form the head of Cetus (the Whale).

Shining at a peak brightness of magnitude 5.7, Uranus is actually bright enough to see in binoculars and small telescopes under dark skies. You can use the three modest stars that form the top of the head of the whale (or sea-monster in some tales) to locate Uranus for the next several months – because the distant planet moves so slowly in its orbit. To help you find it, I posted a detailed star chart here. If you can wait until about 11 pm local time to view it, when it is higher in the sky, you’ll be looking through the least amount of Earth’s disturbing atmosphere.

Reddish Mars is becoming nicely visible now in the eastern pre-dawn sky while it continues to climb away from the pre-dawn sun. From now until October, 2020, Mars will continuously grow in brightness in the sky, and in apparent size in telescopes. In fact, the 2020 Mars opposition is a terrific excuse to get a telescope for the Holidays so you can follow the planet all spring and summer!

When Mars rises at about 5 am local time, look for bright, white Spica, the brightest star in Virgo (the Maiden), sitting four finger widths to Mars’ right (or celestial south). During the week, Mars will drift lower than Spica.

Public Astro-Themed Events

Every Monday evening, York University’s Allan I. Carswell Observatory runs an online star party – broadcasting views from four telescopes/cameras, answering viewer questions, and taking requests! Details are here. On Wednesday nights they offer free public viewing through their rooftop telescopes, including their brand new 1-metre telescope! If it’s cloudy, the astronomers give tours and presentations. Registration and details are here.

At 7:30 pm on Wednesday, November 13, the RASC Toronto Centre will hold their free monthly Recreational Astronomy Night Meeting at the Ontario Science Centre, and the public are welcome. Talks include The Sky This Month, planet-viewing while on a cruise, and one more about backyard astrophotography. These meetings are also streamed live on RASC-TC’s YouTube channel. Check here for details. Parking is free.

On Wednesday evening, November 13 at 7 pm in the Whitby Public Library, the Durham Region Astronomical Association will present Mission to Pluto: From Napkins to New Horizons, a free public talk and webcast about the New Horizons mission. The speaker is Max King, astrophysicist at the University of Toronto. Details are here.

On Friday, November 15 from 7 to 9 pm, join staff at the Kortright Centre for Conservation for Astronomy Night – A Night with the Stars featuring a talk and sky tour. Tickets and details are here.

This Fall and Winter, spend a Sunday afternoon in the other dome at the David Dunlap Observatory! On Sunday afternoon, December 8, from noon to 4 pm, join me in my Starlab Digital Planetarium for an interactive journey through the Universe at DDO. We’ll tour the night sky and see close-up views of galaxies, nebulas, and star clusters, view our Solar System’s planets and alien exo-planets, land on the moon, Mars – and the Sun, travel home to Earth from the edge of the Universe, hear indigenous starlore, and watch immersive fulldome movies! Ask me your burning questions, and see the answers in a planetarium setting – or sit back and soak it all in. Sessions run continuously between noon and 4 pm. Ticket-holders may arrive any time during the program. The program is suitable for ages 3 and older, and the Starlab planetarium is wheelchair accessible. For tickets, please use this link.

Keep looking up, and enjoy the sky when you do. I love questions and requests – so, send me some!