Admiring Andromeda, Spots on Max Jupiter, and the Full Oak Moonlight Minimizes the Geminids!

In this long exposure composite during the Geminids Meteor Shower by Yin HaoC, the bright “twin” stars of Castor and Pollux are framed by the meteors, which appear to radiate from that point in space. (NASA APOD for December 15, 2017)

Hello, Early-December Stargazers!

Here are your Astronomy Skylights for the week of December 8th, 2024 by Chris Vaughan. Feel free to pass this along to your friends and send me your comments, questions, and suggested topics. You can also follow me on Twitter as @astrogeoguy! Unless otherwise noted, all times are expressed in Eastern Time. To subscribe to these emails please click this MailChimp link.

If you’d like me to bring my Digital Starlab portable inflatable planetarium to your school or other daytime or evening event in Simcoe, Grey, and Bruce Counties, or deliver a virtual session anywhere, contact me through AstroGeo.ca, and we’ll tour the Universe, or the Earth’s interior, together! My book with John A. Read entitled 110 Things to See With a Telescope is a guide to viewing the deep sky objects in the Messier List – for both beginners and seasoned astronomers. DM me to order a signed copy!

The moon will be waxing towards full next weekend, so it will spoil this year’s Friday peak of the Geminids meteor shower. I describe the sights of Andromeda, talk about earliest sunset, and highlight this week’s many shadow transits on Jupiter, which was recently at opposition. Read on for your Skylights!

Earliest Sunset

If you live near the latitude of Toronto, Canada, which is about 44° N, Tuesday will deliver your earliest sunset of the year – at 4:40 pm local time. The sun will continue to rise a bit later each morning until the end of December. All in all, the total amount of daylight we see each day will continue to diminish until the solstice on December 21, and then the daylight hours will gradually start to increase again. The rate that night decreases and daylight increases reaches a maximum at the March equinox.

The Geminids Meteor Shower

The Geminids, one of the most spectacular meteor showers of the year, is active from November 19 to December 24 annually while Earth passes through the cloud of sand-sized grains dropped by an asteroid designated (3200) Phaethon. By the way, the number in the brackets is Phaethon’s official designation. Official numbers are assigned once an object’s orbit is determined. Phaethon was discovered on October 11, 1983 and got its number in 1985. As of today, the Minor Planet Center list is up to 1,419,657 objects! Phaethon, which is about 6 by 4 km in size, approaches closer to the sun than any other asteroid. It shuttles from inside the orbit of Mercury to beyond Mars’ orbit every 526 days.

The number of Geminids meteors will gradually ramp up to a peak during the wee hours of Saturday morning, December 15, and then decline rapidly on the following nights. Unfortunately, this year’s shower will be hampered by bright moonlight. If you make the attempt to see some, stand where the moon is hidden behind something, or head outside around 4 am local time, when the moon will be sinking out of sight.

Geminids meteors are often bright, intensely colored, and slower-moving than average. In the Americas, expect to see some Geminids meteors beginning after dark on Friday evening, and then upwards of 120 meteors per hour around 2 am local time on Saturday – the time when the sky overhead will be pointing toward the densest part of the debris field. True Geminids will appear to streak away from a position near Gemini’s bright stars Castor and Pollux, but the meteors can appear anywhere in the sky, so just keep looking up and around.

Admiring Andromeda

Last week here I took you on a tour of the stars and deep sky objects in the constellation of Perseus (the Hero) and shared the Greek myth of his encounter with Andromeda (the Princess) and her parents Queen Cassiopeia and King Cepheus. The moon will increasingly interfere with our stargazing this week, but let’s focus on Andromeda today so that you can take me outside with you and tour her stars from about December 17 onward, when the moon will be rising late.

Andromeda is one of the original classical constellations, and is 19th largest by area (out of the 88 official constellations). Also known as the Chained Lady, she is depicted as laying prone with her body and legs extending to the east (left) – the latter formed by two chains of stars that are connected at one corner of Pegasus’ Great Square and diverge towards her feet. A row of dimmer stars that extends upwards toward the Milky Way represents her chains, but modern star charts don’t draw lines between any of the medium-bright stars in that part of the sky.

Like Pegasus, Andromeda’s location north of the celestial equator means that her stars are visible from everywhere on Earth except Antarctica. A number of ancient cultures saw a woman’s figure in those stars. You can view a nice portrait of her here. (Parental discretion is advised.) The ancient Chinese also envisaged legs – but used a different arrangement of stars. The Navajo saw her stars as a great desert lizard.

Andromeda is visible throughout the fall and winter, but in early November she is found high in the eastern sky, and almost directly overhead during mid-evening. She is connected to Pegasus on her western (right) side. Her brightest star, named Alpheratz “the Horse’s Shoulder”, marks her head, and also serves as “third base” of Pegasus’ large, baseball diamond-shaped Great Square. The faint stars of Pisces (the Fishes) swim below her, while Triangulum (the Triangle) is just to her lower left (east) abutting her lower leg. The distinctive W-shaped of Andromeda’s mother Cassiopeia sparkles above her, while her beloved Perseus shines to her left (east), under her feet. The sky beyond her chains hosts the constellation of Lacerta (the Lizard).

Facing southeast in mid-evening during December, let’s tour the best parts of Andromeda. Her head is marked by the bright star Alpheratz (or Alpha Andromedae). It’s a hot, blue-white supergiant star located only 97 light-years away from us. The spectrum of this star’s light indicates that it is highly enriched in the metal mercury. To see the rest of the princess, look for two slightly curving horizontal lines of three modest stars each that extend to the lower left (northeast) from Alpheratz. The lower leg stars are brighter than their higher counterparts. The lines diverge as you move away from her head, the way her gown would spread out towards her feet. If you’d like a star map of Andromeda to follow along with my tour, use this picture from Freestarcharts.com.

Tracing the lower line of three stars from Alpheratz, reddish Delta Andromedae (or δ And) sits roughly a palm’s width lower left (east) of Alpheratz, marking the princess’ lower shoulder. The next star, another palm’s width farther on, is a bright reddish star called Mirach. The star’s name comes from the Arabic phrase al-Maraqq meaning “the loins” or “the loincloth”. This is a cool, red giant star located 200 light-years from Earth. It produces 1,900 times more light than our sun! Mirach happens to have a 10 million light-years-distant elliptical galaxy tucked in closely above it called Mirach’s Ghost (or NGC 404) – but you’ll need a large telescope and a moonless night to see its fuzzy little patch. (Pay special attention to Mirach as we’ll return to it later.)

Continuing down to the left by a fist’s diameter, we reach one of Andromeda’s feet – the bright double star named Almach “desert lynx”. Almach’s beautiful golden and sapphire stars easily are seen in a small telescope. The two stars differ in both brightness and colour.

About midway between Mirach and Almach, and a thumb’s width above the line connecting them, sits a medium-bright magnitude 4.1 star named Titawin (or Upsilon Andromedae). Titawin’s main star is a binary system with a faint, orbiting companion. Four Jupiter-sized exoplanets discovered between 1996 and 2010 orbit that star! Three of the planets have been named after Andalusian scientists: Saffar, Samh, and Majriti. The magnitude 3.55 star that marks Andromeda’s higher foot, a palm’s width above Almach, is an orange-tinted star named Nembus that used to be part of Perseus, so it’s also named both 51 Andromedae and Upsilon Perseii. (In the past, stars were frequently re-assigned by map-makers).

Andromeda’s higher shoulder, located several finger widths above Delta Andromedae, is marked by a modestly bright star named Pi Andromedae.

Now, head back to Mirach and follow Andromeda’s chained waist upwards. Sitting about four finger widths above (or celestial NNW of) Mirach is a dimmer white star designated Mu Andromedae (or μ And). A few finger widths above Mu is another even dimmer star named Nu Andromedae (or v And). Mirach and those two other stars form the Andromeda’s Girdle asterism.

Look for a large, fuzzy patch of sky situated just above Nu, the highest star. That’s Messier 31 (or M31, for short), better known as the Andromeda Galaxy – one of the night sky’s best sights! Under dark skies, you should be able to glimpse the galaxy using just your unaided eyes. Its massive spiral is a twin to our Milky Way galaxy. It covers an area of the sky equivalent to six full moon diameters end-to-end and two moon diameters top-to-bottom. It has a bright core and dim oval halo that is oriented east-west. That should be roughly left-right at the time you’ll be looking.

At about 2.5 million light years away, M31 is one of the farthest objects that can be seen with unaided human eyes! It’s best to view it with binoculars, which will fit all of its immensity into the same view. Using a good sized telescope at low magnification on an dark night, more treasures are revealed. Two smaller elliptical galaxies glow just above and below the main galaxy. The smaller of the two, named M32, is positioned nearer to M31’s centre. It is 100,000 light-years closer to us than the big galaxy. The other companion, named M110, is 100,000 light-years farther from us. We’re going to collide with the Andromeda Galaxy in 4 or 5 billion years, but that’s another story!

Aim your binoculars a fist’s diameter above the Andromeda Galaxy, or above and between Alpheratz and the top star of Cassiopeia (named Caph), and look for a scattering of medium-bright stars with a variety of colours. They represent the rocks Andromeda is chained to. In 1787 astronomer Johann Bode used a handful of the stars to create a constellation named Honores Friderici or Frederici Honores (the Regalia of Frederic) in honour of Frederick the Great, the king of Prussia who had died in the previous year. The stars Lambda, Kappa, and Iota Andromedae combined to form a kind of hilt and the stars Psi and Omicron Andromedae above and below them, respectively, formed the sceptre. You can see a (parental discretion advised) depiction of that defunct constellation here.

Andromeda contains two more interesting deep sky objects. A large, loose open star cluster named NGC 752, another terrific target for your binoculars, is located below and between Almach and Mirach. Look for a tight little triangle of warm-tinted stars in its core and a bright pair of close-together stars at its edge. On the opposite end of the constellation, about 1.5 fist diameters above Alpheratz is the Blue Snowball (or NGC 7662). This magnitude 8.3 planetary nebula, the decaying corpse of a star of similar mass to our own sun, is fairly easy to see in backyard telescopes – but it’s tiny. In your telescope, look for a non-twinkling dot with a faint blue-green colour.

Owners of medium-sized or larger telescopes can also see the small, but enchanting flying saucer of the Silver Sliver Galaxy (or NGC 891) which is located two thumb widths below (or 3.4° to the celestial east of) Almach. It’s a spiral galaxy oriented nearly edge-on to us.

The Moon

The moon will increasingly dominate the evening sky worldwide this week as it waxes from its first quarter phase this morning (Sunday) to a full moon next Sunday morning. The moon looks spectacular while it’s close to full, but it doesn’t look very impressive through binoculars or a telescope at that time because the sun isn’t casting shadows from any of its features. Not all is lost, however. More about that in a minute.

In the meantime, our natural satellite will be well worth looking at as this week begins. Today (Sunday) the half-illuminated moon will already be well on its way across the southeastern sky in late afternoon. (It’s perfectly safe to view the moon in daylight as long as no one aims optics near the sun.) After sunset, the yellowish dot of Saturn will appear to the moon’s lower right, and then the stars of Aquarius (the Water-Bearer) around them will show up. The moon will follow Saturn down the west around midnight.

The northern section of Sunday’s moon will be dominated by the eastern semi-circle of the great Imbrium Basin. It is ringed by three spectacular and tall mountain ranges that were pushed up during its formation. The northern arc is the Lunar Alps (or Montes Alpes). The southern arc is the Apennine Mountains (or Montes Apenninus). The less continuous Caucasus Mountain (or Montes Caucasus) range that curves between them is breached where Imbrium connects to Mare Serenitatis. Imbrium’s big central crater Archimedes will be on the sunny side of the terminator boundary. Under magnification, watch for the subtle wrinkles snaking across the basin’s grey, flat floor.

The waxing moon will spend Monday and Tuesday swimming through Pisces (the Fishes), but you won’t see its faint stars against the glare. On Monday night, the terminator’s increasing westward curve will light up more of Mare Imbrium and bisect the large crater Copernicus within it. If you can’t see the crater with unaided eyes, switch to your binoculars or any telescope.

On Wednesday the moon will still be shining in daylight after lunch. From dusk onward, the brightest stars of Aries (the Ram) will shine to its upper left. The Imbrium Basin’s full expanse will be bathed in sunlight. Sinus Iridium “the Bay of Rainbows” resembles an ear on the left side of Imbrium’s round face.

On Thursday night, the bright, nearly full moon will shine near the planet Uranus. Use binoculars to look for the medium-bright star Botein (or Delta Arietis) shining below the moon. If you place Botein just at the upper edge of the binoculars’ field of view, Uranus will appear as a dull, blue-green “star” near the bottom of the field of view. Uranus is far easier to see without a bright moon nearby, so take note of Botein’s location with respect to the bright Pleiades star cluster (aka Messier 45, Subaru, and the Seven Sisters) off to its left and return to Uranus on another night. In a dark sky, you can see the magnitude 5.7 planet without optical aid. A backyard telescope will reveal its tiny disk.

On Friday evening, some parts of the world will see the orbital motion of the bright, nearly full moon carry it through the Pleiades star cluster. While bright moonlight overwhelms fainter objects, viewing the encounter during evening twilight, especially through binoculars, will make a pretty, and fascinating, sight. Skywatchers in Europe and Africa will see the moon among the Pleiades’ scattered stars. Observers in Asia and the Americas will have to settle for seeing the moon shining to their upper right (or celestial west) and lower left (or celestial east), respectively. That night, very bright Jupiter and Taurus’ brightest star Aldebaran will be side by side below the moon. Take a photo!

If you miss Friday’s photo op, try again on Saturday. Shortly after the very bright moon clears the rooftops in the east after dusk on Saturday, the brilliant planet Jupiter will rise to join it. The duo will make a lovely photo opportunity when composed with some nice foreground scenery. As the moon and Jupiter climb the eastern sky, the bright winter stars will surround them, including the yellowish star Capella on their upper left and reddish Aldebaran to their right, both part of the huge winter hexagon asterism. The moon and Jupiter will culminate due south towards midnight and set in the west before dawn. By then the diurnal rotation of the sky will lift the moon, now full, above Jupiter.

The moon will reach its full phase at 4:02 am EST, 1:02 am PST, or 09:02 Greenwich Mean Time on Sunday, December 15. The December full moon, colloquially known as the Oak Moon, Cold Moon, and Long Nights Moon, always shines in or near the stars of Taurus (the Bull) or Gemini (the Twins). Since it’s opposite the sun on this day of the lunar month, the moon becomes fully illuminated, and rises at sunset and sets at sunrise. Full moons during the winter months at mid-northern latitudes reach as high in the midnight sky as the summer noonday sun, and cast similar shadows.

Indigenous groups have their own names for the full moons, which marked time and lit the way of hunters and travelers at night before modern conveniences like flashlights. Unlike our regulated western calendar, they linked the full moon to what is happening in the environment around them.

The Ojibwe of the Great Lakes region call the December full moon Manidoo Giizisoons, the “Little Spirit Moon”. For them it is a time of purification and of healing of all Creation. Their January moon is Gichi-Manidoo Giizis, the “Great Spirits Moon”. It is manifested through the northern lights, and is a time to honour the silence and realize one’s place within all of Great Mystery’s creatures. The Woodland Cree of the Central Canada call the December moon Thithikopiwipisim, the “Hoar Frost Moon”, when frost sticks to leaves and other things outside.

The bright moon will have waned a little when it rises around sunset next Sunday. By then it will have slide east into Gemini (the Twins). The prominent crater Copernicus is located in eastern Oceanus Procellarum – due south of big Mare Imbrium and slightly northwest of the moon’s centre. Copernicus’ 800 million year old impact scar is visible with unaided eyes and binoculars – but telescope views will reveal many more interesting aspects of lunar geology.

Several nights before the moon reaches its full phase, Copernicus exhibits heavily terraced edges (due to slumping), an extensive ejecta blanket outside the crater rim, a complex central peak, and both smooth and rough terrain on the crater’s floor. Around full moon, Copernicus’ ragged ray system, extending 800 km in all directions, becomes prominent. Use high magnification to look around Copernicus for small craters with bright floors and black haloes – impacts through Copernicus’ white ejecta that excavated dark Oceanus Procellarum basalt and even deeper highlands anorthosite.

The impact that created the bright crater Tycho, which is located in the south-central area of the moon, produced streaks of bright material that extend in multiple directions across the moon’s near side – but they are missing from its lower left (western) side. Another particularly interesting ray system surrounds the crater Proclus. The 27 km wide crater and its ray system are visible in binoculars. They are located at the lower left edge of Mare Crisium, the round grey basin near the moon’s upper right edge (northeast on the moon). The Proclus rays, 600 km in length, only appear on the eastern, right-hand side of the crater, and within Mare Crisium, suggesting that the impactor arrived at a shallow angle from the southwest. The small crater Menelaus on the southern edge of Mare Serenitatis hosts some small rays. A long, possibly unrelated, ray passes through both Menelaus and the mare. (Note that east and west are reversed on the moon).

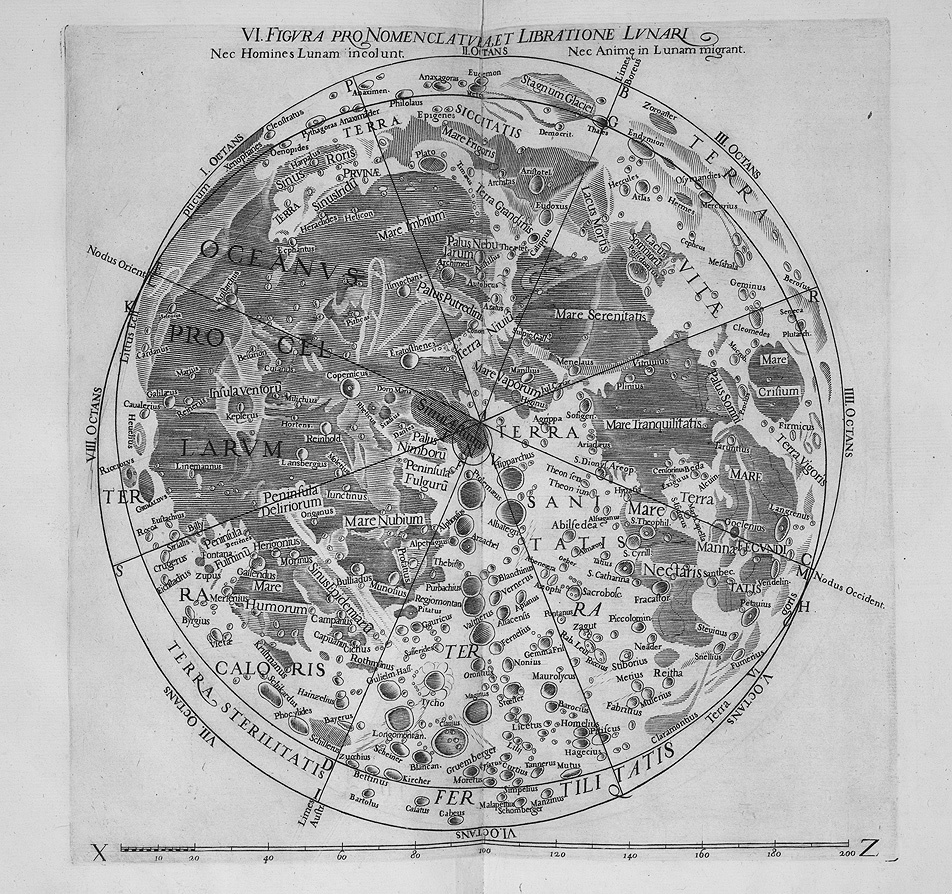

The terms “maria” (the dark regions) and “terra” (the heavily cratered bright regions) were coined by Galileo Galilei after he began to view the moon in his little telescope around 1610. The rest of the moon’s naming system was developed by Jesuit priest Giovanni Riccioli. In 1651 he published a labeled moon map that all later maps derive from. He used the names of living and dead scientists and philosophers for the craters, assigning ancient notables to the north of the moon and “modern” (to him, anyway) personages in the south. He placed teachers and their famous students together.

The maria are all named for weather and states of mind, except for Mare Humboldtianum and Mare Smythii, who were famous explorers, and Mare Cognitum and Mare Moscoviense, discovered later on the moon’s far side. Fittingly, Riccioli placed the radical proponents of the heliocentric theory, Copernicus, Aristarchus, and Kepler in the Sea of Storms – and he honoured fellow Jesuits Grimaldi and Clavius with prominent craters.

The Planets

Mercury has passed the sun, and will now be climbing the eastern sky before sunrise. You might be able to see it shining low in the southeast from mid-week onward, especially if you live at tropical latitudes. Turn binoculars away from the horizon before the sun starts to rise.

The rest of the planets are in the evening sky worldwide. Venus is the very bright “Evening Star” gleaming in the western sky every evening. The planet will be visible even before the sky darkens, but the stars will appear around it by the time it sets around 8 pm local time. If you see something that is blinking, or moving left or right, it’s an airplane! Venus will spend December crossing through the stars of Capricornus (the Sea-Goat). When viewed through a telescope or very strong binoculars, the planet will show a waning gibbous phase.

While the sky is still darkening, turn south to spot the yellowish dot of Saturn shining not too high up in the sky. After dark, you might also see the bright star Fomalhaut in the constellation of Piscis Austrinus (the Southern Fish) twinkling about two fist diameters below, and a little to the right, of Saturn. Saturn and the faintish stars of Aquarius (the Water-Bearer) surrounding it will set the west around 11:30 pm local time, but you’ll have clear views of the planet in any backyard telescope until about 9:30 pm. Don’t forget that the pretty moon will shine to the upper left of the ringed planet tonight (Sunday).

Saturn’s bright, but extremely thin rings effectively disappear when they become edge-on to Earth every 15 years. Since we are only four months away from that, in late March, 2025, the rings already appear as a thick line drawn through the planet. Good binoculars can hint that Saturn has rings, but any size of telescope will show the rings and some of Saturn’s larger moons, too. In most years, Saturn’s moons are sprinkled around the planet, unlike Jupiter’s Galileans moons, which are always in a line. But while Earth is within months of being aligned with Saturn’s ring plane, its moons remain within a zone drawn through the rings.

Saturn’s largest and brightest moon Titan “TIE-tan” never wanders more than five times the width of Saturn’s rings from the planet. The much fainter moon named Iapetus “eye-YA-pet-us” can stray up to twelve times the ring width during its 80-day orbit of Saturn. The next brightest moons Rhea “REE-ya”, Dione “Dee-OWN-ee”, Tethys “Teth-EES”, Enceladus “En-SELL-a-dus”, and Mimas “MY-mass” all stay within one ring-width of Saturn. You may be surprised at how many of those six you can see through your telescope if you look closely when the sky is clear, dark, and calm.

During early evening this week, Titan will start from a position off to Saturn’s right (or celestial northwest) tonight (Sunday), pass just above (celestial north of) Saturn from Friday to Saturday, and then extend to Saturn’s left (or celestial east) next Sunday night. (Remember that your telescope will probably flip the view around.) The rest of the moons will be tiny specks in a line near the rings. Earth’s perspective of the Saturn system will also cause Saturn’s moons and their small black shadows to frequently cross its disk – but you’ll need a very high quality telescope to watch those.

Distant, blue Neptune has been following Saturn across the sky every night, just shy of 1.5 fist widths to the upper left (or celestial ENE) of Saturn and a palm’s width to the lower left of the circle of faint stars that forms Pisces’ western fish. The planet can be seen in a backyard telescope, but only when the moon isn’t too bright nor too close to it – so wait until late next week to look for the planet. Use binoculars to find the upright, tilted rectangle formed by the medium-bright stars 27, 29, 30, and 33 Piscium. Neptune will be the bluish, dull “star” sitting about two finger widths to the upper right (or 2° to the celestial north) of that box.

I mentioned above that the bright moon will pose near Uranus on Thursday, so this is not a great week to look for that planet. This month, the distant ice giant planet is observable all night long about a palm’s width to the right (or celestial southwest) of the bright little Pleiades star cluster in Taurus (the Bull). If you use your binoculars to find the medium-bright stars named Botein and Epsilon Arietis, Uranus will be the dull-looking blue-green “star” located several finger widths below (or southeast of) them. To get you in the vicinity of Uranus, look for the bright star Menkar shining 2.2 fist diameters off to the right of the Pleiades and down a little. Uranus will be a quarter of the way along the line joining the bottom star of the Pleiades to Menkar.

Jupiter just experienced opposition for 2024, so the bright planet will already be gleaming above the northeastern horizon at sunset this week and shining at close to peak brightness in the sky and maximum size in a telescope. From now until early February, Jupiter will be moving west between the horn stars of Taurus (the Bull), which are named Elnath and Zeta Tauri. Those stars will shine to Jupiter’s upper left and lower left, respectively. Jupiter’s westerly motion will also carry it steadily closer to Taurus’ brightest star, reddish Aldebaran, which marks the eye of the bull. This week, Jupiter and Aldebaran will be a generous palm’s width apart, and closing. The winter constellations will shine below Jupiter every day from late evening onward. They will rotate to the planet’s left after midnight.

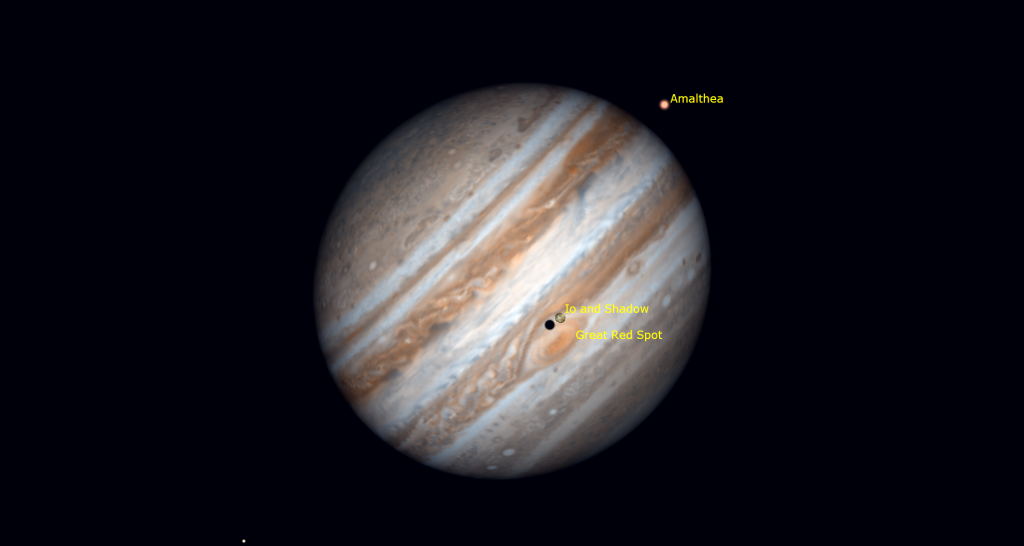

Viewed in any size of telescope, the planet will display a disk striped with brown dark belts and creamy light zones, which are aligned parallel to its equator. With a better grade of optics, Jupiter’s Great Red Spot, a cyclonic storm that has raged for hundreds of years, becomes visible for several hours when it crosses the planet every 2nd or 3rd night. For observers in the Americas, that GRS will cross Jupiter’s disk during early evening on Tuesday, Thursday and next Sunday, and also towards midnight Eastern time on Monday, Wednesday, and Friday night. If you have any coloured filters or nebula filters for your telescope, try enhancing the spot with them.

Any size of binoculars will show you Jupiter’s four Galilean moons named Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto lined up beside the planet. Those moons complete orbits of the planet every 1.7, 3.6, 7.2, and 16.7 days, respectively. If you see fewer than four moons, then one or more of them is crossing in front of or behind Jupiter, or hiding in Jupiter’s dark shadow – or two of the moons are very close together, or one moon is eclipsing or occulting another one. All four moons will gather to one side on Monday, Tuesday, and next Sunday night!

From time to time, observers with good quality telescopes can watch the black shadows of the Galilean moons travel across Jupiter’s disk. In the Americas, Ganymede and its large shadow will cross Jupiter on Sunday, December 8 between 5:38 pm and 7:47 pm EST (or 22:38 to 00:47 GMT). Io and its little shadow will cross on Sunday, December 8 between 10:57 pm and 1:08 am EST (or 03:57 to 06:08 GMT). Io and its little shadow will cross with the red spot on Tuesday, December 10 between 5:26 pm and 7:37 pm EST (or 22:26 to 00:37 GMT).

This week the prominent reddish dot of Mars will clear the trees in the east by 9 pm local time. It will cross the sky all night long, chasing Jupiter and Uranus, and end up halfway up the southwestern sky before dawn. Mars is growing bigger and brighter every day as the distance between our two planets diminishes – this week to about 110 million km away. In a telescope, the planet will display a small, ochre disk adorned with some vague darker markings. The surface details will sharpen while Mars gets closer to Earth every day until its opposition night on January 15-16.

Mars will be shining about 1.3 fist diameters below the bright star Pollux, the lower of the “twin” stars of Gemini, but the planet is actually in central Cancer (the Crab). Mars has started a westerly retrograde loop that will last through its mid-January opposition and into late February. This week, the planet will be shining just above (or celestial north of) the large open star cluster in Cancer known as the Beehive, Praesepe, and Messier 44. Mars and the stellar “bees”, which will be scattered across an area more than twice the size of a full moon, will fit into the field of view in binoculars through next week, and then it will move increasingly farther above the cluster.

Public Astronomy-Themed Events

Every Monday evening, York University’s Allan I. Carswell Observatory runs an online star party – broadcasting views from four telescopes/cameras, answering viewer questions, and taking requests! Details are here. They host in-person viewing on the first clear Wednesday night each month. Other Wednesdays they stream views online via the observatory YouTube channel. Details are here.

Keep your eyes on the skies! I love getting questions and requests. Send me some!