An Evening Moon Erases Saturn, Seeing Stars Shoot, Max Mercury and Uranus, and Full Frost Final Supermoon!

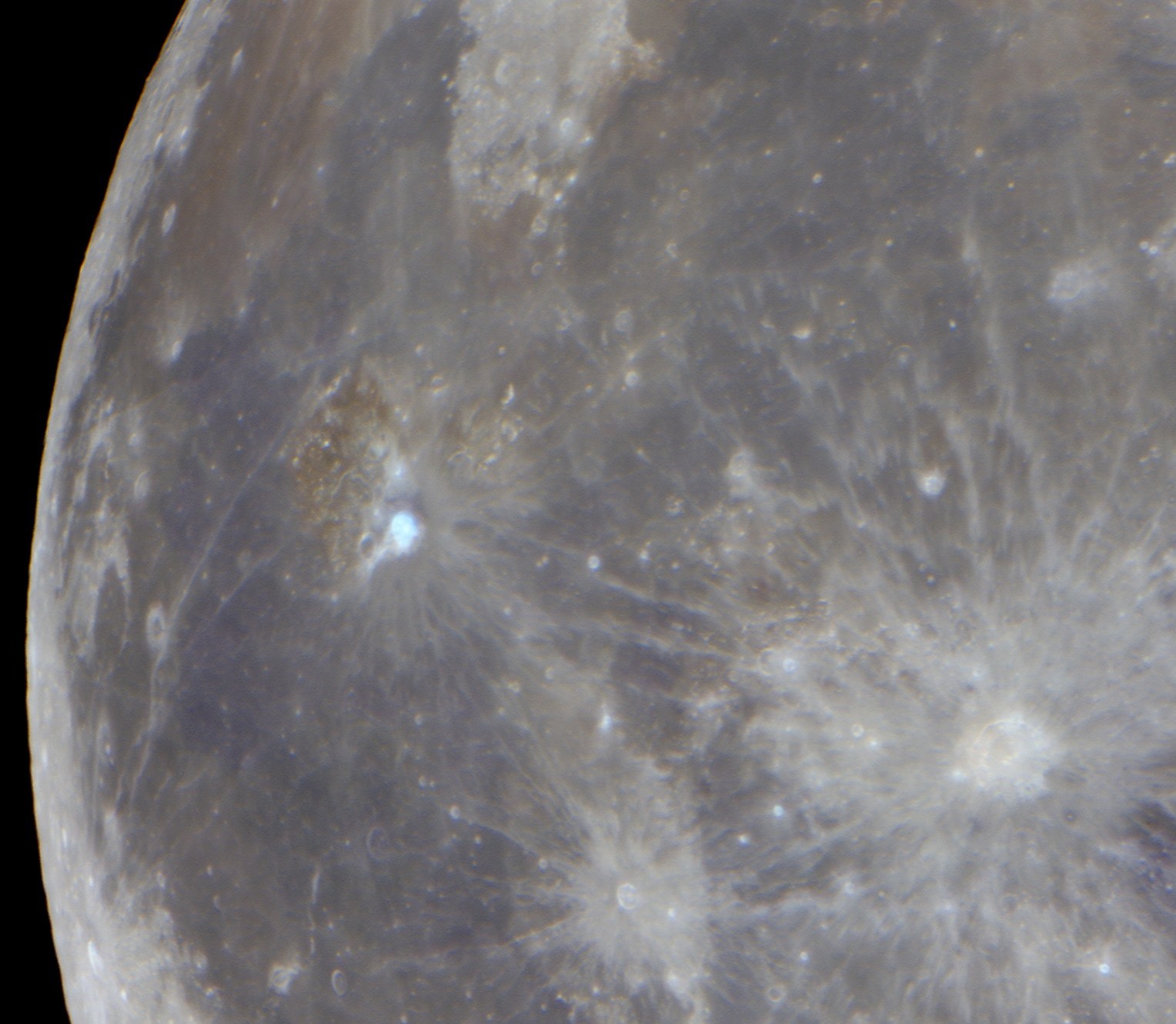

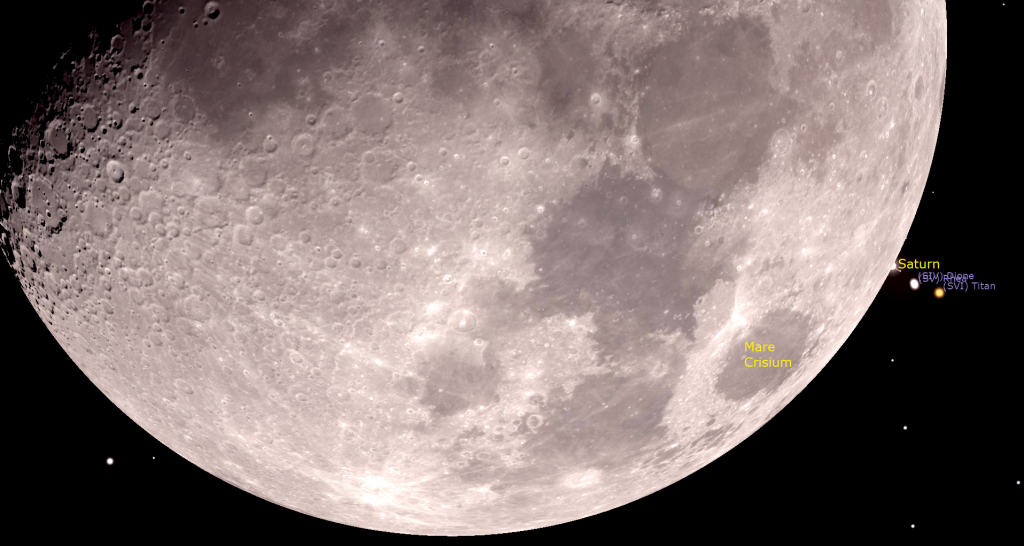

The area around the small, bright crater Aristarchus (left of centre) in Oceanus Procellarum is one of the most colourful portions of the lunar surface. The large ragged ray systems at lower right surround the craters Copernicus and Kepler. (Rolf Hempel via Planetary.org)

Hello, Mid-November Stargazers!

Here are your Astronomy Skylights for the week of November 10th, 2024 by Chris Vaughan. Feel free to pass this along to your friends and send me your comments, questions, and suggested topics. You can also follow me on Twitter as @astrogeoguy! Unless otherwise noted, all times are expressed in Eastern Time. To subscribe to these emails please click this MailChimp link.

If you’d like me to bring my Digital Starlab portable inflatable planetarium to your school or other daytime or evening event in Simcoe, Grey, and Bruce Counties, or deliver a virtual session anywhere, contact me through AstroGeo.ca, and we’ll tour the Universe, or the Earth’s interior, together! My book with John A. Read entitled 110 Things to See With a Telescope is a guide to viewing the deep sky objects in the Messier List – for both beginners and seasoned astronomers. DM me to order a signed copy!

The world will experience two meteor showers and Uranus at opposition this week, but the bright moon in the evening and late-night sky will somewhat spoiling the fun. On the other hand, the moon will occult Saturn for some areas on Sunday and then gleam as a full supermoon worldwide on Friday. Mercury will reach maximum visibility after sunset, the rest of the planets will all shine before midnight, and I explain how meteor showers work and how to see them. Read on for your Skylights!

Meteor Showers 101

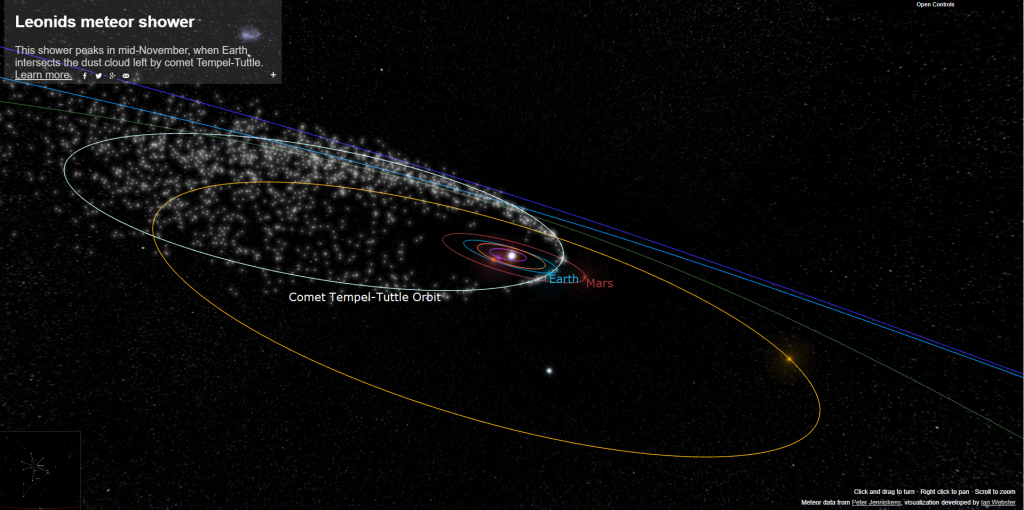

Meteor showers re-occur on the same dates every year when Earth’s orbital motion around the sun carries us through zones of small particles left behind by multiple passes of periodic comets. When those comets sweep through the inner solar system, the warmth of the sun causes them to outgas and eject dust-sized and sand-sized (and sometimes larger) cometary particles along their orbit. Over millennia, and many, many orbits, the material accumulates within an elongated, tube-shaped cloud in interplanetary space. An analogy would be the material that falls out of a dump truck as it rattles along. The roadway eventually gets pretty dirty after the truck has driven the same route a number of times. The solar wind is not strong enough to blow the debris away. There are about 110 established meteor showers, of which about 16 are worth looking up for.

When the Earth plows through the debris cloud, some of its particles are caught by our gravity and burn up as they fall through our atmosphere at speeds on the order of 200,000 km/hr. The friction caused by grains moving that quickly through the air generates intense heat that ionizes the air along its path – producing the long glowing trails we see as meteors. We believe that Mercury, Venus, and Mars are also experiencing meteor showers.

The duration of a meteor shower depends on the width of the particle cloud in space and the angle at which we intersect it, i.e., how long Earth takes to pass through it. The number of meteors will increase nightly as Earth ventures more deeply into the debris field, peak when the particles are most plentiful, and then taper off on the following nights.

A shower’s intensity depends on the type of particles in it, and on whether we pass through the densest portion of the debris field, or merely skirt the edges. Due to small variations in orbits, any shower’s performance can vary from year to year. The other factor that controls how many meteors we see is moonlight. Meteor showers are scheduled by the Earth’s orbit around the sun, which repeats every year. The phases of the moon are on a much different schedule.

The moon’s phases repeat every 29 days, 12 hours, and 44 minutes, 3 seconds – which astronomers call its synodic period, or a lunar month. If you do some arithmetic, you’ll work out that we get about 12 and one-third lunar months every year. That means that a particular meteor shower can peak while the moon is at any phase. Full moons overwhelm most meteors, new moons leave the sky dark, and the other moon phases affect showers to varying degrees. If the moon is going to be shining in the sky on peak night, you can often arrange to do your meteor-watching a night or two before or after the peak night, when the moon won’t as bad.

By the way, moon phases do repeat on a long time scale. Any given phase/date combination will repeat after 19 years, or 235 lunar months – with an error of only 2 hours. That metonic cycle or enneadecaeteris, from the Ancient Greek word ἐννεακαίδεκα, meaning “nineteen”, has been incorporated into the Babylonian and Hebrew lunisolar calendars, and was observed by other ancient skywatchers. An example might be a full moon on Christmas (in 2034) or on Halloween (in 2039), or a particularly fine year for the August Perseids meteors (in 2029, 2034, and 2037).

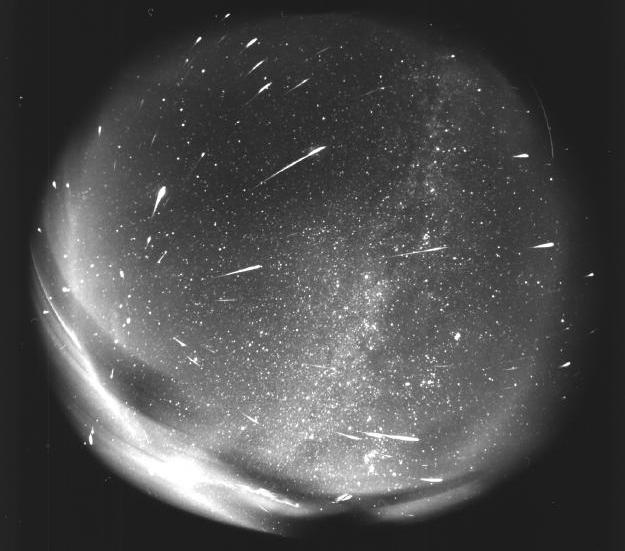

Meteors can appear anywhere in a dark sky, but those from a particular shower will be streaking away from a location in the sky called the radiant, the point on the celestial sphere that the Earth is travelling toward during the shower. The sky there is like the front windshield of your car being hit by bugs or snow while you drive. The constellation hosting the radiant’s location gives each shower its name. The Earth’s “windshield” is highest in the sky after midnight. When radiants are low, many of the meteors are out of sight below the horizon, so we recommend viewing meteors during the wee hours if you can.

Meteor showers can be worldwide events, but some are better seen from either the northern or southern hemisphere, depending on whether its radiant is north or south of the celestial equator. For example, Orion’s Belt sits nearly on top of the celestial equator and Taurus (the Bull) and Leo (the Lion) are both located a little north of it, so all of their showers are worldwide events.

To see the most meteors, try to find a safe, ideally rural, viewing location with as much open sky as possible. If you can hide bright lights or the moon behind a building or tree, that will help. You can start watching as soon as the sky becomes dark. That’s a good time to catch the rarer, very long meteors produced by particles skipping across the Earth’s upper atmosphere. Don’t worry about watching the radiant, since the meteors near it will be heading directly towards you and will have very short trails. When you see a meteor, try to trace its path backwards to see if it points to the radiant constellation. You can expect to see solitary sporadic meteors on any dark night. Those ones won’t follow the “radiant rule”!

Bring a blanket for warmth and a chaise to avoid neck strain, plus snacks and drinks. Try to keep watching the sky even while chatting with friends or family – they’ll understand. Call out when you see one; a bit of friendly competition is fun!

Don’t look at your phone or tablet – its bright screen will spoil your dark adaptation. If you must use a screen, turn the brightness down, enable red mode, or cover it with red film. Disabling app notifications will reduce the chances of unexpected bright light, too. And remember that the narrow fields of view that binoculars and telescopes will not help you see meteors.

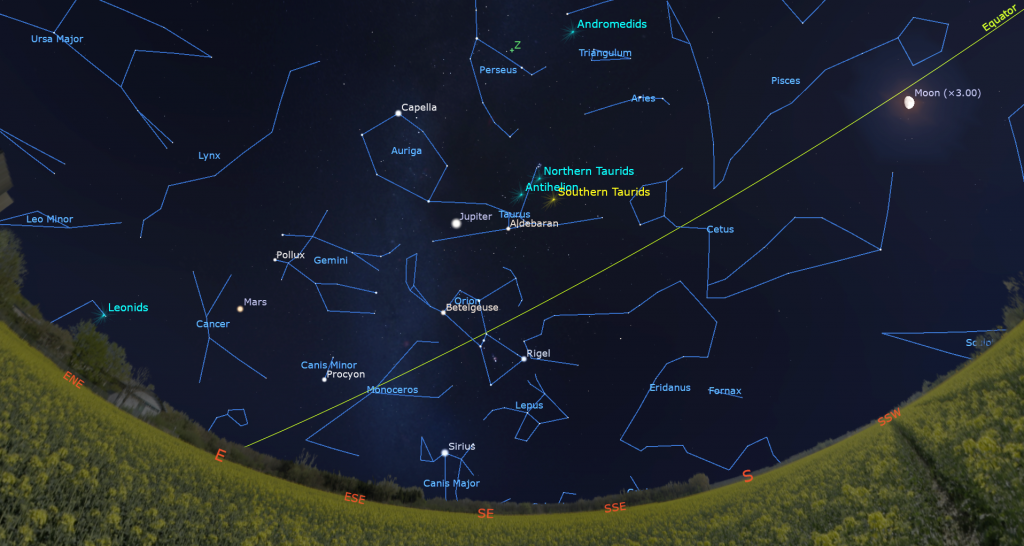

Meteor Showers This Week

The long-lasting Northern Taurids meteor shower, the second shower derived from Comet 2P/Encke, is active worldwide from October 20 to December 10 annually. It will reach its maximum overnight on Monday, November 11 in the Americas. The best viewing time for North American skywatchers will be the hours around midnight when the shower’s radiant near the Pleiades star cluster in Taurus will be well above the horizon, and especially after the bright moon sets around 2:30 am local time on Tuesday morning. The Northern Taurids shower typically delivers 5 meteors per hour at its peak. The larger-than-average grain sizes of the particles often produce colorful fireballs. Watch for lingering “smoke” dissipating after a particularly bright meteor.

The Leonids Meteor Shower, which is derived from bits of material dropped when periodic Comet 55P/Tempel-Tuttle traverses the inner solar system every 33 years, runs from November 5 to December 2, annually. The peak of the shower, when up to 15 meteors per hour are predicted, will occur from Saturday night, November 16 into Sunday morning, November 17 in the Americas, when Earth will be traversing the densest part of the comet’s debris train. While you should see a few Leonids after dusk on Saturday evening – many with persistent trains – more of them will be apparent on Sunday in the hours before dawn, when the radiant in the head of Leo will be high in the southeastern sky. Unfortunately, a bright moon will shine all night long during this year’s shower, obscuring the fainter meteors. Many Leonids have persistent trains and strong colour. Happy viewing!

The Moon

The moon will shine during the evening and then more and more overnight worldwide as we move through this week. For the first half of this week, our waxing natural satellite will look spectacular through binoculars and telescopes, and then it will become a fully illuminated, brilliant night-light on the coming weekend.

Today (Sunday, November 10), the waxing gibbous moon will climb the southeastern sky all afternoon. Once the sky begins to darken after sunset, face south and look for the prominent, yellowish dot of Saturn easily close enough to the moon for them to share the view in binoculars. Later, observers located in a broad zone extending from the Atlantic Ocean and southwest across southern Florida, the Caribbean, Central America, and northwestern South America can use their unaided eyes, binoculars, and backyard telescopes see the moon pass in front of, or occult, Saturn. Surrounding regions will see the moon merely shining close to Saturn. Use an app like Stellarium, Star Walk 2, or Sky Safari to look up the occultation times for your location. In Miami, the dark, northern edge of the moon will cover Saturn at 9:25 pm EST. Saturn will emerge from behind the lit side of the moon a distance north of oval Mare Crisium at 10:07 pm EST. Be sure to be watching a few minutes ahead of each time, and look for Saturn’s moons in a telescope, too.

The moon will become brighter and fuller each night as it increases its angle from the sun. It will swim through the faint stars of Pisces (the Fishes) from Monday to Wednesday. The pole-to-pole lunar terminator boundary will sweep west across Oceanus Procellarum, the “sea of storms”, the widespread dark region on the moon’s left-hand side. Three prominent craters break up the expanse of Oceanus Procellarum. Large Copernicus is the easternmost of the craters. Its extensive, ragged ray system intermingles with that of the smaller crater Kepler to its southwest. The small, but very bright crater Aristarchus positioned northwest of them occupies the southeastern corner of a diamond-shaped plateau that is one of the most colorful regions on the moon. NASA orbiters have detected high levels of radioactive radon there. Use a telescope and high magnification to view features like the large, sinuous rille named Vallis Schröteri. Its snake-like form begins between Aristarchus and next-door Herodotus and meanders across the plateau.

From Thursday onwards, the moon will look full and become extremely bright. You might spot Hamal and Sheratan, the brightest stars of Aries (the Ram) above the moon on Thursday. Brilliant Jupiter will gleam off to the lower left (or celestial east). While the moon is near its full phase, bright rays can be seen radiating from the younger craters on the lunar near side. The impact that created the bright crater Tycho, which is located in the south-central area of the moon, produced streaks of bright material that extend in multiple directions across the moon’s near side. Another particularly interesting ray system surrounds the crater Proclus. The 27 km wide crater and its ray system are visible in binoculars. They are located at the lower left edge of Mare Crisium, the round grey basin near the moon’s upper right edge (northeast on the moon). The Proclus rays, 600 km in length, only appear on the eastern, right-hand side of the crater, and within Mare Crisium, suggesting that the impactor arrived at a shallow angle from the southwest. The small crater Menelaus on the southern edge of Mare Serenitatis hosts some small rays. A long, possibly unrelated, ray passes through both Menelaus and the mare. (Note that east and west are reversed on the moon).

The November full moon, traditionally known as the Beaver Moon or Frost Moon, always shines within or near the stars of Taurus and Aries. The moon will reach its full phase at 4:29 pm EST, 1:29 pm PST, or 21:29 Greenwich Mean Time on Friday. Indigenous groups have their own names for the full moons, which lit the way of the hunter or traveler at night before modern conveniences like flashlights. The Anishinaabe people of the Great Lakes region call this one Mnidoons Giizis Oonhg, the “Little Spirit Moon”, a time of healing. The Cree Nation of central Canada calls it Kaskatinowipisim, the “Rivers Freeze-up Moon”, when the lakes and rivers start to freeze. The Haudenosaunee Confederacy (Iroquois / Mohawk) of Eastern North America call it Kentenhko:wa, the “Time of Much Poverty Moon”.

Full moons that occur during the cold months in North America will climb as high in the sky at midnight as the summer noonday sun, and cast similar shadows. Since the moon passed its closest point to Earth, or perigee, on Thursday morning, only 1.4 days prior, this will also be the last of four consecutive supermoons in 2024, appearing about 6% larger and 16% brighter than an average full moon. The astronomical term for a supermoon is a lunar perigee syzygy!

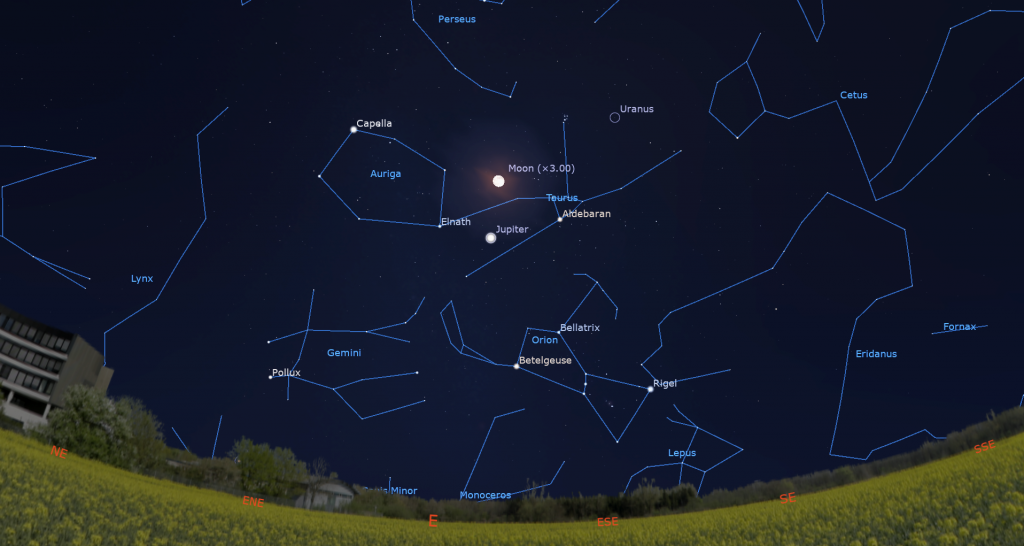

Friday night’s moon will be shining between the Pleiades star cluster and Uranus in Taurus (the Bull), but you’ll need binoculars to see the planet or those stars against the glare. Jupiter will be shining two fist diameters to the moon’s left. During the evening hours, the bright stars of winter will be arranged below them. The pair will climb to their highest position in the southern sky after midnight and then descend in the west as sunrise approaches. By then the diurnal rotation of the sky will shift Jupiter to the moon’s left. From Saturday to Sunday, the moon, now waning gibbous, but still very bright, will hop from one side of Jupiter to the other. Take some photos!

The Planets

For another two weeks, all the planets will be visible in the evening and late-night sky. Then speedy Mercury will drop out of sight and move into the eastern pre-dawn sky starting in mid-December.

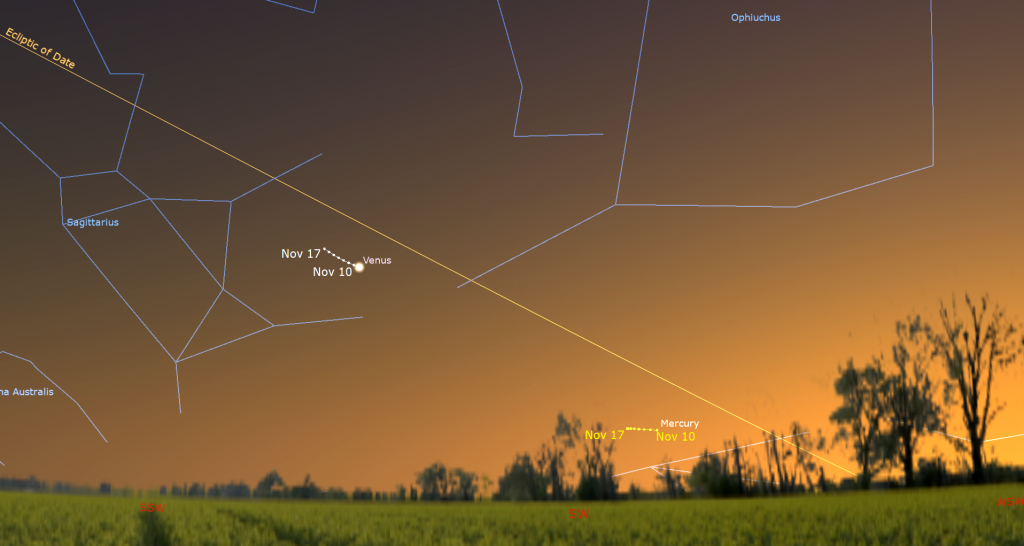

This week, Mercury will continue to appear just above the southwestern horizon, setting an hour after the sun does. Its position 2 degrees below (or south of) the severely slanted evening ecliptic is keeping the planet too low in the sky for easy viewing from northerly latitudes, but if you live close to the tropics or in the Southern Hemisphere, Mercury is putting on a fine and easy showing for you. In a telescope, Mercury will display a waning gibbous shape that grows a bit larger every day as its orbit brings it closer to Earth. On Saturday, Mercury will extend to its widest separation of 23 degrees east of the Sun, and maximum visibility for its current evening apparition. The optimal viewing times at mid-northern latitudes will start around 5 pm local time. Don’t aim binoculars above the western horizon until after the sun has fully set.

If you fail to find Mercury, you can’t miss Venus! The magnitude -4.0 planet will catch your eye in the lower part of the southwestern sky even before sunset – though you might need to stand where trees or buildings don’t block your view of it. Venus will set two hours after sunset, so you have plenty of time. (If you see something bright that is moving left or right, or blinking, it’s an airplane.) The stars will have appeared by the time Venus is setting. Since Venus is completing a passage beyond the sun, it will increase its angle from the sun every day and move closer to Earth, causing it to slowly wane in illuminated phase and grow larger in telescopes. Venus will be safe to view through binoculars or a telescope after the sun has completely disappeared. Under magnification the planet will show a blurry (due to the extra air you are looking through) 73%-illuminated, football shape.

I mentioned above that the moon will shine close to Saturn this evening (Sunday), and occult the ringed planets for observers located in a broad zone extending from the Atlantic Ocean and southwest across southern Florida, the Caribbean, Central America, and northwestern South America. Saturn will stay in the lower part of the southern evening sky after the moon moves away. You might also see the bright star Fomalhaut in the constellation of Piscis Austrinus (the Southern Fish) twinkling about two fist diameters below, and a little to the right.

Saturn and the faintish stars of Aquarius (the Water-Bearer) surrounding it will set the west around 1:15 am local time, but you’ll have clear views of the planet in any backyard telescope until at least 10:30 pm. Sharp eyes and binoculars will show you a bent-line trio of stars collectively named Psi1,2,3 Aquarii sparkling a few finger widths to Saturn’s lower left, and two redder stars named Phi and Chi Aquarii to Saturn’s left and lower left, respectively. The entire group will fit in your binoculars’ field of view. An even brighter star named Hydor will appear a thumb’s width to Saturn’s upper right (or celestial WNW). On Saturday, Saturn will complete a westward retrograde loop that it began in July. Retrograde loops occur when Earth, on a faster orbit closer to the sun, passes more distant solar system objects “on the inside track”, making them appear to move backwards across the stars for a while. Saturn’s loop covered about a palm’s width, or 6 degrees, of the celestial sphere.

Saturn’s bright, but extremely thin rings effectively disappear when they become edge-on to Earth every 15 years. Since they will do that in late March (while in the pre-dawn sky), the rings already appear as a thick line drawn through the planet. Good binoculars can hint that Saturn has rings, but any size of telescope will show the rings and some of Saturn’s larger moons, too. In most years, Saturn’s moons are sprinkled around the planet, unlike Jupiter’s Galileans moons, which are always in a line. But while Earth is within months of being aligned with Saturn’s ring plane, its moons remain within a zone drawn through the rings.

Saturn’s largest and brightest moon Titan “TIE-tan” never wanders more than five times the width of Saturn’s rings from the planet. The much fainter moon named Iapetus “eye-YA-pet-us” can stray up to twelve times the ring width during its 80-day orbit of Saturn. The next brightest moons Rhea “REE-ya”, Dione “Dee-OWN-ee”, Tethys “Teth-EES”, Enceladus “En-SELL-a-dus”, and Mimas “MY-mass” all stay within one ring-width of Saturn. You may be surprised at how many of those six you can see through your telescope if you look closely when the sky is clear, dark, and calm.

During this week, Titan will start from off to Saturn’s upper right (or celestial west) tonight (Sunday), pass just above (celestial north of) Saturn on Tuesday, and then stretch more and more to Saturn’s lower left (or celestial east) by next Sunday night. (Remember that your telescope will probably flip the view around.) The rest of the moons will be tiny specks in a line near the rings. Earth’s perspective of the Saturn system will also cause Saturn’s moons and their small black shadows to frequently cross its disk – but you’ll need a very high quality telescope to watch those.

The distant blue planet Neptune is following Saturn across the sky every night, but the bright moon will swamp the planet, even in telescopes. Slow-moving Neptune will spend all of this year in western Pisces (the Fishes). During early evening it will be in the southeastern sky about 1.5 fist widths to the lower left (or 15° to the celestial ENE) of Saturn and a palm’s width below the circle of stars that forms Pisces’ western fish.

Uranus will be climbing the eastern sky during evening this month, positioned about a palm’s width to the right (or celestial southwest) of the bright little Pleiades star cluster in Taurus (the Bull). On Saturday Uranus will reach opposition, the night of the year when it is closest to Earth, “only” 2.78 billion km or 154 light-minutes away. The planet will shine at a peak brightness of magnitude 5.61 as it crosses the sky all night long, making it readily visible in binoculars and backyard telescopes. Uranus’ small, blue-green dot will also appear slightly larger in telescopes for about a week centered on opposition night. That’s good, because the planet will be hard to observe while the bright moon shines near it on Friday. Uranus has been moving slowly retrograde westwards through western Taurus. If you use your binoculars to find the medium-bright stars named Botein and Epsilon Arietis, Uranus will be the dull-looking blue-green “star” located several finger widths below (or southeast of) them. To get you in the vicinity of Uranus, look for the bright star Menkar shining 2.2 fist diameters off to the right of the Pleiades. Uranus will be a quarter of the way along the line joining the bottom star of the Pleiades to Menkar.

How thrilling it is to see Jupiter dominating the eastern sky in early evening! It will reach its highest point due south during the wee hours and then be a beacon in the western sky toward sunrise. From now until early February, Jupiter will be creeping west between the horn stars of Taurus (the Bull), Elnath and Zeta Tauri. They will shine to Jupiter’s upper left and lower left, respectively. Jupiter will also slide ever closer to the bull’s brightest star, reddish Aldebaran. For now, it’s shining less than a fist’s diameter to the left (or celestial east) of that star.

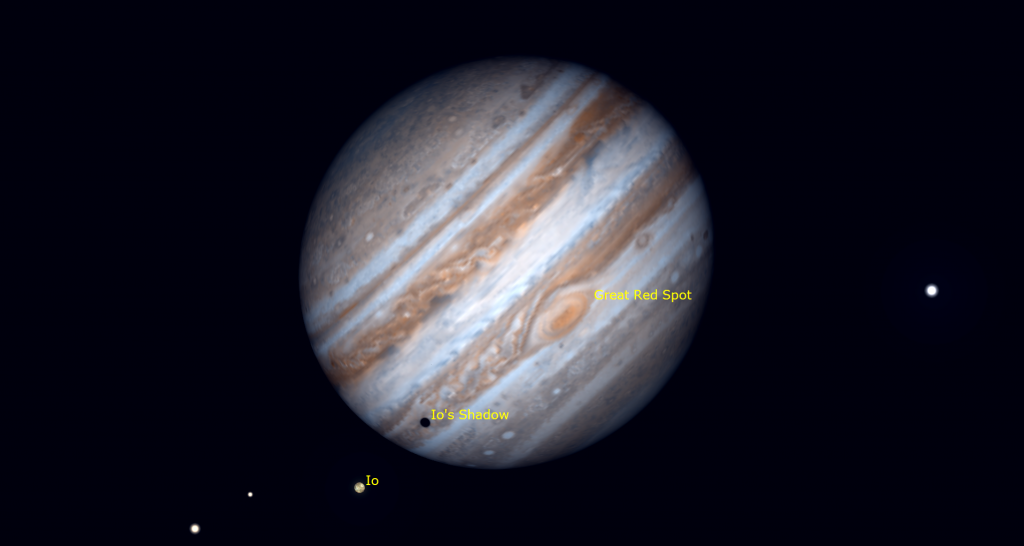

Any size of binoculars will show you Jupiter’s four Galilean moons named Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto lined up beside the planet. Those moons complete orbits of the planet every 1.7, 3.6, 7.2, and 16.7 days, respectively. If you see fewer than four moons, then one or more of them is crossing in front of or behind Jupiter, or hiding in Jupiter’s dark shadow – or two of the moons are very close together, or one moon is eclipsing or occulting another one. All of the moons will gather to one side of the planet on Wednesday night and three of them will clump together on Saturday night.

Jupiter will continue to get a little brighter and a little larger until its opposition night in a few weeks. Even a small, but decent quality telescope can show you Jupiter’s dark belts and light zones, which are aligned parallel to its equator. With a better grade of optics, Jupiter’s Great Red Spot, a cyclonic storm that has raged for hundreds of years, becomes visible for several hours when it crosses the planet every 2nd or 3rd night. For observers in the Americas, that GRS will cross Jupiter’s disk during early evening on Monday, Wednesday, and Saturday night, and also around midnight Eastern time on Sunday, Tuesday, Friday, and next Sunday night. If you have any coloured filters or nebula filters for your telescope, try enhancing the spot with them.

From time to time, observers with good quality telescopes can watch the black shadows of the Galilean moons travel across Jupiter’s disk. In the Americas, the small shadow of Europa will cross on Monday morning, November 11 between 1:08 am and 3:38 am EST (or 06:08 to 08:38 GMT). Io’s little shadow will cross along with Jupiter’s red spot on Friday night, November 15 between 10:47 pm and 12:58 am EST (or 03:47 to 05:58 GMT on Saturday).

Thanks to the clocks winding back last weekend, Mars will available to us after it clears the eastern rooftops around 11 pm local time. Its reddish dot will chase Jupiter across the sky all night while remaining positioned below Pollux, the lower of the “twin” stars of Gemini. Early risers can easily find Mars shining high in the southwestern sky at sunrise with Jupiter. In a telescope this week, the red planet will display a small, reddish disk without much detail – yet. As Mars gets closer to Earth every day until its opposition night on January 15-16, we will see it grow in apparent size and brighten.

Public Astronomy-Themed Events

Every Monday evening, York University’s Allan I. Carswell Observatory runs an online star party – broadcasting views from four telescopes/cameras, answering viewer questions, and taking requests! Details are here. They host in-person viewing on the first clear Wednesday night each month. Other Wednesdays they stream views online via the observatory YouTube channel. Details are here.

On Saturday, November 16 from 7 to 9 pm EDT, the in-person Astronomy Speakers Night program at the David Dunlap Observatory in Richmond Hill, Ontario will feature June Parsons. His talk will be JWST and the Search for Life in Unexpected Places.After the presentation, participants will view interesting celestial objects through telescopes on the lawn (weather permitting). More information is here and the registration link is at ActiveRH.

Keep your eyes on the skies! I love getting questions and requests. Send me some!