Comet Leonard Looms Larger, the Waxing Moon Poses with Planets, and Geminids Germinate!

On November 24, 2021 Comet C/2021 A1 (Leonard) passed between two well-known galaxies, the Whale (top right) and the Hockey Stick (lower left), otherwise known as NGC 4631 and NGC 4656, respectively. Gregg Ruppel of Tucson, Arizona captured this beautiful image of the rendezvous through his telescope-mounted astro-camera. This image, which spans 1 degrees of the sky left-to-right, was NASA’s APOD for Dec 3, 2021. More recent images of the comet passing Messier 3 are available at Gregg’s terrific website at http://www.greggsastronomy.com/c2021%20A1%20Leonard.html

Hello, December Stargazers!

Here are your Astronomy Skylights for the week of December 5th, 2021 by Chris Vaughan. Feel free to pass this along to your friends and send me your comments, questions, and suggested topics. You can also follow me on Twitter as @astrogeoguy! Unless otherwise noted, all times are expressed in Eastern Time. To subscribe to these emails please click this MailChimp link.

I can bring my Digital Starlab portable inflatable planetarium to your school or other daytime or evening event, or teach a session online. Contact me through AstroGeo.ca, and we’ll tour the Universe, or the Earth’s interior, together! My terrific new book with John A. Read entitled 110 Things to See With a Telescope is a guide to viewing the deep sky objects in the Messier List – for both beginners and seasoned astronomers. DM me to order a copy!

Comet Leonard will reach peak size and visibility in the eastern pre-dawn sky on the coming weekend, so I share some tips for viewing it and some basic comet info. Mars will be there, too. Meanwhile, the waxing crescent moon will shine in the western sky after sunset as it wanders through the gathering of three bright planets: Jupiter, Saturn, and Venus. The year’s most prolific meteor shower is ramping up. Read on for your Skylights!

Comet Basics

Comets are among the most captivating of sights for skywatchers. Their glowing green heads and glorious tails, powered by the sun’s warmth and buffeted by its solar wind, sweep across the sky. The brightest comets, easily visible with unaided eyes, are legendary. But those are extremely rare, often only visible from limited regions of the globe, and for only a brief time. The arrival of new, bright comets is completely unpredictable, adding to their mystique. But one or two dimmer comets are usually observable in binoculars or small telescopes every month, if you know where to find them.

Comets can be one-time visitors that are flung out of the solar system by the sun or destroyed in its heat. Others traverse the solar system like interplanetary shuttle-craft.

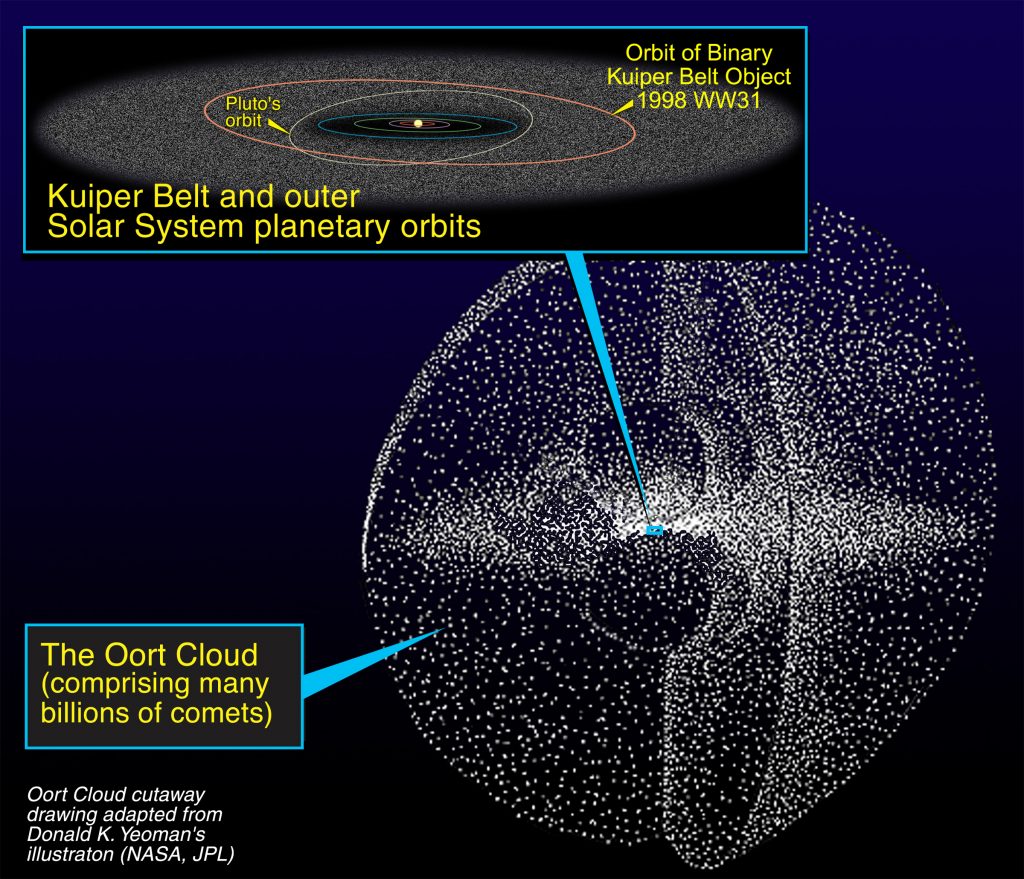

Comets, named for the Greek phrase for “having long hair”, come from the Kuiper Belt and Oort Cloud, cold regions far beyond Neptune’s orbit. Here, primordial ice and other volatile elements survived after our newly-formed sun cleared that material from between the planets. You can think of them as “dusty icebergs”, so low in density that you could crush a piece in your hand. Astronomers believe that the gravitational tug of a passing star or an outer planet can cause one of those icy bodies to fall towards the sun – a journey that can take thousands of years. Once they venture near enough to it, the sun’s heat and radiation releases gas and dust trapped in the ice, producing the characteristic coma around the comet’s nucleus, and the tail.

Some of the coma is ionized by the sun’s radiation, causing it to glow with blue-green light. The ions align with the solar magnetic and electric fields around the comet, forming a straight ion tail pointed directly away from the sun. Meanwhile, the disintegration of the ice releases trapped dust and larger particles that are dropped in the comet’s wake as a dust tail, like a dirt-filled truck on a bumpy road. When the comet gets close enough to Earth, we can see the glowing ions and the dusty tail lit by reflected sunlight.

Some of the lighter dust particles are pushed away by solar wind pressure. If the comet is travelling laterally as it approaches the sun, the difference between the travel directions of the comet and the solar wind cause the dust tail to curve in a spectacular arc. In fact, many comets sport a curved yellowish dust tail in one direction and a straight bluish ion tail in another direction.

As a comet drops towards the sun, it brightens and accelerates towards perihelion, or closest approach to the sun. Many comets fail to miss the sun and are destroyed during perihelion. This was the case for Comet ISON in late November, 2013. After perihelion, it was predicted to re-enter our skies in spectacular fashion. But it disintegrated during its passage. A NASA video of that event is here.

Comets that survive perihelion can be flung out of the solar system forever, making them one-time visitors only. The rest enter stable orbits that return them to the sun on periods of years to millennia.

In ancient times, no one knew that some comets were returning periodically. In 1705, while researching historical records from previous comet appearances, English astronomer Edmund Halley noted that three comets shared the same orbit, and were likely a single periodic comet. He calculated a return date, but died before it re-appeared as predicted in 1759. It was named Halley’s Comet (despite the fact that it had been observed by many individuals since 240 BCE). The competition to first see Halley’s Comet launched the career of Charles Messier, and led to his famous list of “not-comets”.

For the next 200 years or so, periodic comets were named for the discoverers who calculated their orbits (although sometimes, prior observers were added to the name), but this became confusing when the same people discovered several comets. The confusion was alleviated by numbering all periodic comets in order of discovery, starting with “1P/Halley”. The list has reached “436P/Garradd”, discovered in Fall, 2021.

Since 1995, new comets have been given designations that indicate their type, the date of discovery, and the discoverer. The prefixes “P/” for periodic, “C/” for non-periodic, “X/” for uncertain, and “D/” for destroyed or lost, give the type of comet. Appended to it are the year of discovery and a letter code indicating which of the 24 half-months it was discovered in, where “A” represents January 1-15 and “Y” is December 16-31. Next, a number indicates whether it was the first, second, etc. comet discovered in that half-month. Finally, the name(s) of the discover(s) and/or the name of the robotic camera system used in the discovery, are appended. This system has been applied retroactively to all periodic comets, so many individual comets have multiple designations. That duplication can sometimes mess up amateurs who are using apps to search for observable comets.

The best times to hunt comets are during dark moonless nights. Expect the comet to appear as a faint greenish blob (quite different from a star, but resembling a galaxy). If it has a tail, it will be much fainter, and pointing away from the sun. If you use a telescope, be sure to search at low power (50x) initially, and then magnify once you have it in view, to 150X or more. Don’t be afraid to try long exposure photographs, either through the eyepiece, or using a tripod-mounted camera.

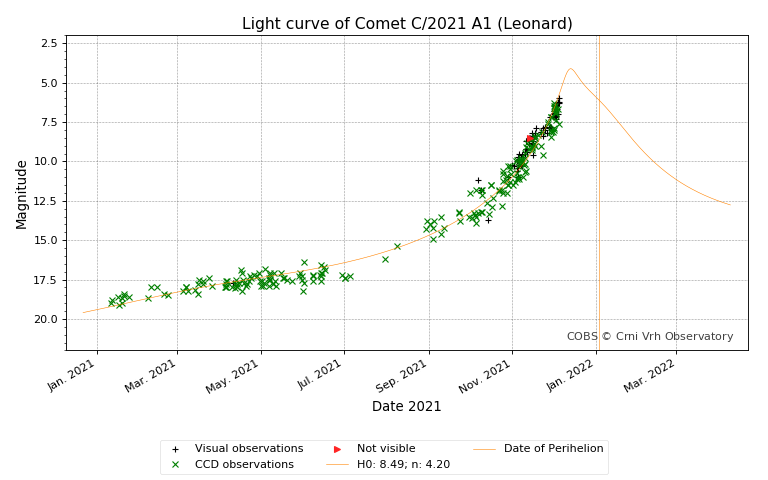

For celestial objects, the visual magnitude number increases as the brightness decreases. If a comet brightens to magnitude 4 or 5, you should be able to see it with your unaided eyes from an area free of artificial light or moonlight. A small pair of binoculars should show comets as faint as visual magnitude of 8 or 9 under very dark skies. Large binoculars and small telescopes will capture comets down to about magnitude 11. An 8” (203 mm) reflector or SCT telescope can see comets beyond magnitude 12. A larger aperture telescope will work even better. But for visual observing, I wouldn’t go out of my way to see a comet dimmer than magnitude 8 or 9.

Several good websites will tell you what comets are currently observable. www.Cometchasing.skyhound.com lists current and upcoming comets, ranked in order of visibility, with notes about when and where to look, and what instrument is required (naked eyes, binoculars, small telescope, etc.). Links provide a printable finder chart showing each comet’s path over the month. COBS, the Comet Observation Database records observers’ data and plots brightness graphs for current comets.

Seiichi Yoshida’s Weekly Information about Bright Comets provides observing notes, finder charts, recent photographs, and a light curve showing the predicted brightness profile over time as well as brightness estimates contributed by observers. His Visual Comets in the Future page lists the comets observable during evening, midnight, and the pre-dawn, month by month into the future.

Best Week for Comet Leonard

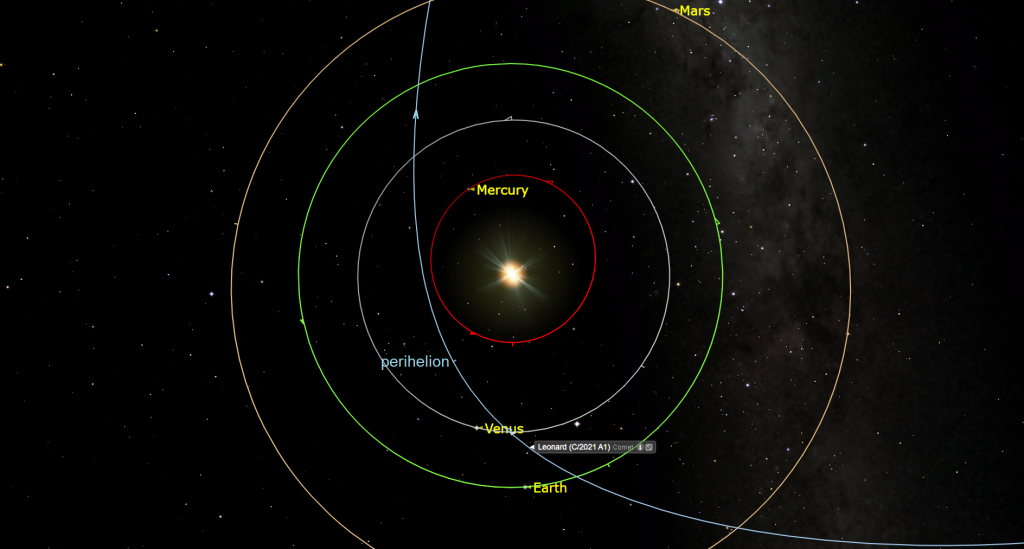

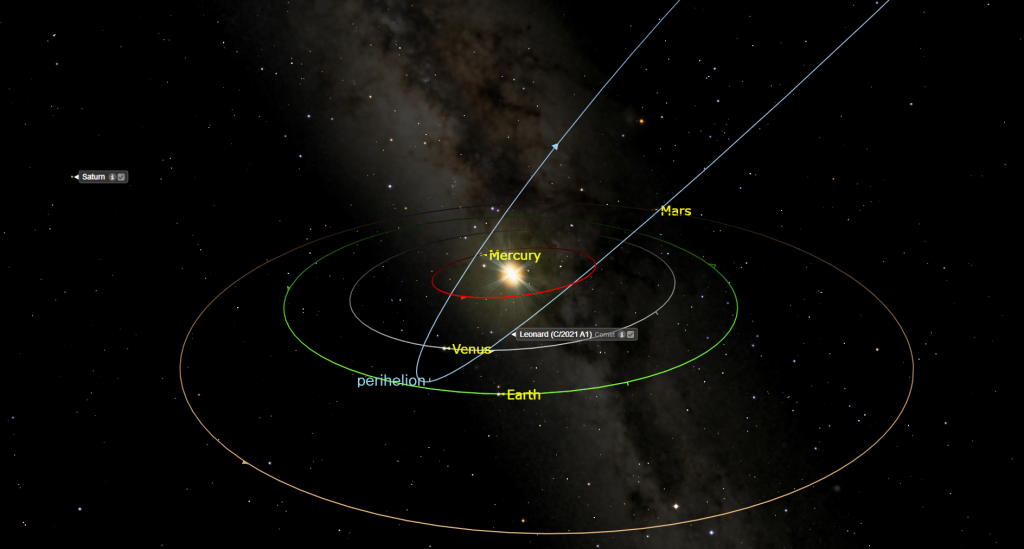

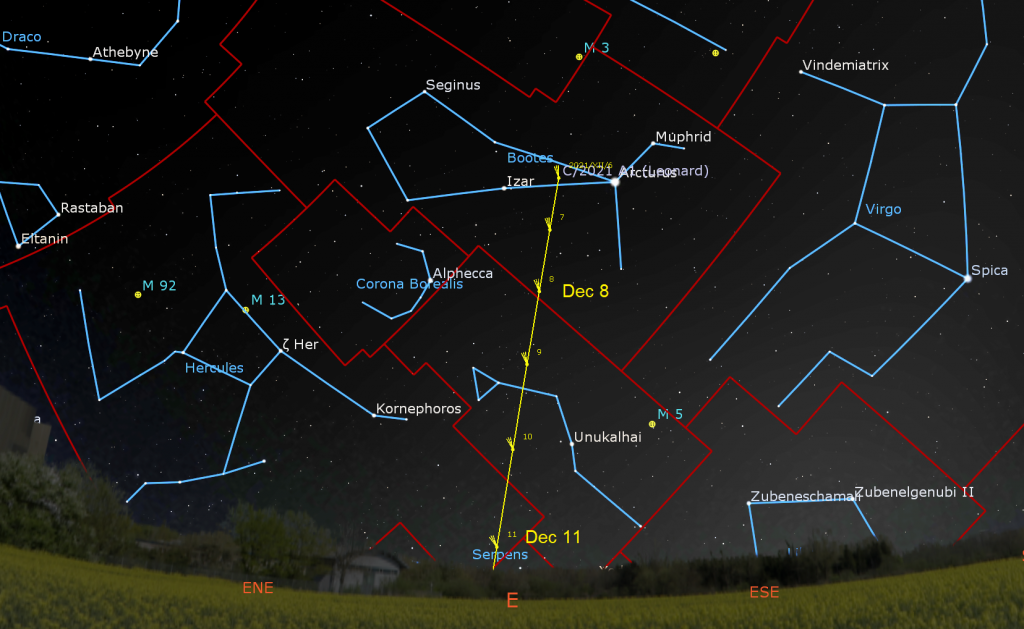

If you live at a mid-northerly latitude, the coming week will provide the prime window of opportunity to see the best-performing comet of 2021 – if you don’t mind rising before dawn! The comet, named C/2021 A1 (Leonard), was discovered by G. J. Leonard at the Mount Lemmon Observatory near Tuscon, AZ on January 3, 2021. When it was discovered, near the handle of the Big Dipper, the comet was 5 AU (or 750 million km) from the Sun. After Comet Leonard’s orbit was calculated, astronomers were able to predict that it should brighten enough to see with unaided eyes when it enters the inner solar system this month.

Comet Leonard will be brightest and largest in the sky when it passes nearest to Earth, or perigee, in the early hours of Sunday, December 12, 2021. Unfortunately, its celestial path will be pulling it closer to the sun every morning – so, on that date, the comet will rise at about 6 am local time in a sky that will already be brightening – hampering our view. If the comet does brighten sufficiently by then, and the eastern sky is cloud-free, we’ll be able to see it on Sunday for a short time before sunrise. But we’ll also be viewing the comet through a much thicker blanket of Earth’s distorting atmosphere, and horizon haze.

On the following morning, Monday, December 13, the comet will be hidden in the sun’s glare. From Tuesday, December 14 onwards, Comet Leonard will sit low in the southwestern skyglow after sunset, and then it will travel right to left (or celestial southeastward) above the horizon for several weeks. All the while, it will be steadily receding from Earth and fading, especially after it passes the sun on January 3. (Viewers in the southern hemisphere will finally have their own chance to see the comet in evening after December 15.)

My advice is to start your attempts to see the comet now! Luckily for us, the moon will not interfere with our views! On Monday morning, the comet should already shine at about magnitude 6, well within reach of binoculars and backyard telescopes, especially from a dark location. Once you’ve had a look under magnification, try using your unaided eyes! Comet Leonard will rise at about 2 am local time and then climb the eastern sky until dawn. In Canada, and countries with the same mid-northern latitudes, astronomical twilight will begin at about 6 am local time – so the hour between 5 and 6 am will offer the best combination of dark sky and higher sky position (or altitude).

On Monday, the comet will be located a slim palm’s width to the right (or 5.25 degrees to the celestial northeast) of the very bright star Arcturus. That’s close enough for them to share the view in binoculars – but you’ll be better off keeping the bright star out of frame.

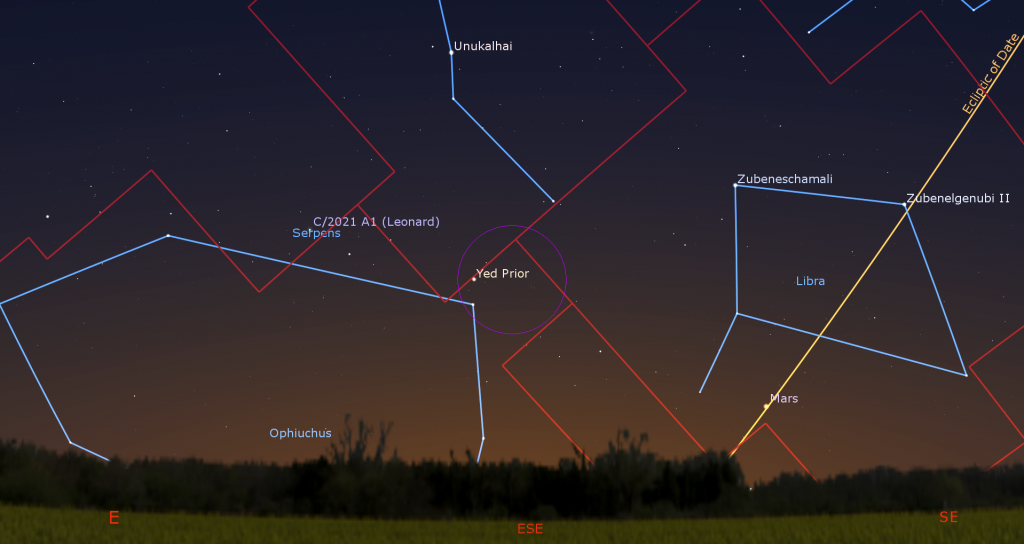

Comets move rather quickly compared to the background stars. On each subsequent morning, the comet will descend by several finger widths, dropping farther below (celestial southeast of) Arcturus. On Wednesday morning, Comet Leonard will pass a fist’s diameter to the right of Corona Borealis’ brightest star Alphecca, and then enter Serpens Cauda (the Serpent’s Head) for Thursday and Friday. Look for Comet Leonard sitting a slim palm’s width to the left of the snake’s brightest star, magnitude 2.6 Unukalhai (or Alpha Serpentis) on Friday.

Saturday morning, December 11 at around 6:30 pm local time could deliver our best views of all. The comet will be about 14 degrees above the eastern horizon, and just above the brighter stars of sideways Ophiuchus (the Serpent Bearer). On Sunday, perigee time, Comet Leonard will sit in central Ophiuchus, a few finger widths to the left (or 3 degrees northeast) of the globular clusters M12 and M10. Start looking soon after the comet rises – at about 6 am local time.

A few more tips. If your location is dark, the comet should resemble a faint fuzzy patch or unfocused star. Its fainter tail will extend roughly upwards, i.e., pointed away from the horizon. In binoculars or a telescope, look for a faint hint of green. If you use Stellarium or a mobile app, you should update the orbital elements for solar system objects so that the comet’s position is plotted correctly. Then use the app’s flip buttons to show the same orientation that your telescope produces and find the star patterns that should be surrounding the comet. If you still can’t see it, try tapping the telescope while you are looking. Making a faint fuzzy object “dance” a little will make it more visible.

I wish you clear skies and good luck! Let me know if you see it, or photograph it. And feel free to tag me on social media if you post about it.

The Moon

This will be the best week of the lunar month to view our planet’s sibling! The moon will shine prettily in the evening sky while it waxes in phase each night. The zone along the pole-to-pole terminator, the boundary separating the lit and dark hemispheres, will be spectacularly illuminated with slanted sunlight. The views through binoculars and backyard telescopes will be breathtaking – and the sight-seeing will vary night after night. With the sun setting before 5 pm local time, even the youngest stargazers can take a look before bedtime. But bundle them up!

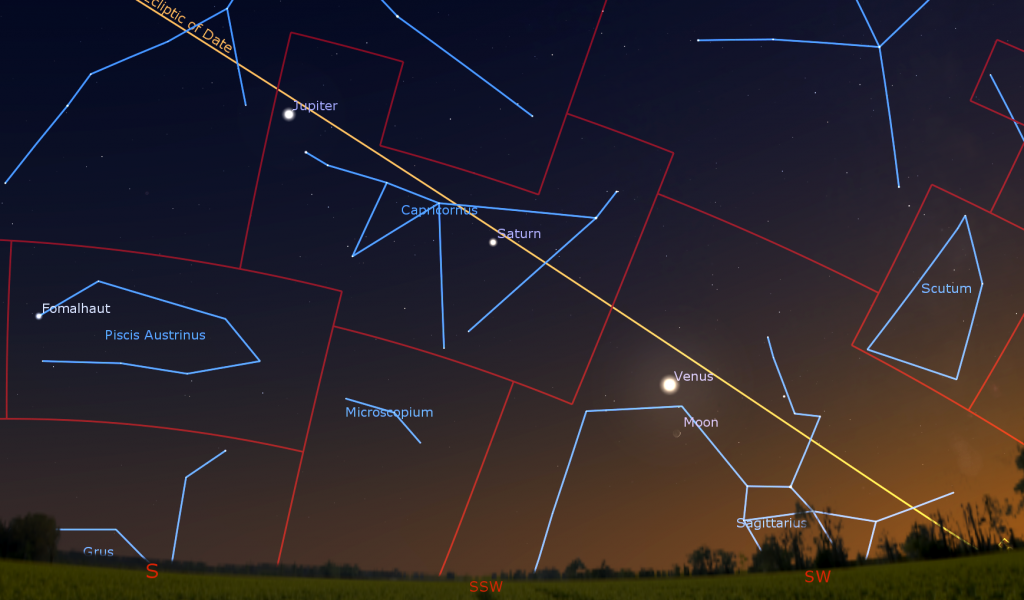

Today (Sunday) the young crescent moon will shine above the southwestern horizon for a short time after sunset. On Monday, its slim crescent will appear a few finger widths below (or 3 degrees to the celestial south of) the very bright planet Venus, close enough for them to share the view in binoculars. Viewed in a telescope that night, Venus will display a 24%-illuminated crescent phase – similar to, but somewhat thicker than, the moon’s. On either night, ensure that the sun has fully set before aiming optical aids into the western sky. Keep a look out for Earthshine. That’s sunlight reflected off Earth wgich slightly brightens the un-illuminated parts of the crescent moon.

The moon’s monthly visit with the bright gas giant planets Saturn and Jupiter will kick off after dusk in the southern sky on Tuesday. Before the sky has fully darkened, try using binoculars to find the yellowish dot of Saturn positioned a palm’s width to the upper left (or 6 degrees to the celestial northeast) of the crescent moon. Or wait until Saturn is visible with your unaided eyes. Much brighter and whiter Jupiter will be shining off to their upper left, and even brighter Venus will gleam to their lower right. On Wednesday evening, the moon will hop east to shine below and between the bright, white dot of Jupiter and somewhat fainter and creamy-colored Saturn. Very bright Venus will blaze to their lower right (celestial west) until it sets at about 7 pm local time. Finally, on Thursday night the moon will move to sit a generous palm’s width to the left of Jupiter. The moon will then bid adieu to those bright planets until January 4-5.

The moon will complete the first quarter of its monthly journey around Earth at 01:35 Greenwich Mean Time on Saturday, December 11. That translates to 8:35 pm EST on Friday, December 10. At first quarter its 90 degree angle from the sun will cause us to see the moon exactly half-illuminated – on its eastern side. At first quarter, the moon always rises around mid-day and sets around midnight, so it is also visible in the afternoon daytime sky. The gibbous moon will end this week swimming with Cetus the Whale and Pisces the Fishes. (Next week it will cross the Winter Football asterism!)

Meteor Shower News

The Geminids Meteor Shower, always one of the most spectacular of the year, runs from December 4 to 16 annually. The Geminids will ramp up to a peak number of meteors after midnight on Tuesday night, December 14, and then the shower will rapidly taper off during the following days. You can expect to see more and more Geminids meteors each night as we approach next Monday-Tuesday – so keep an eye to the sky if you are outside on any clear night this week.

Geminids meteors are often bright, intensely coloured, and slower moving than average because they are produced by sand-sized grains dropped by an asteroid designated 3200 Phaethon. You can watch for Geminids after the sky darkens on Monday evening until dawn on Tuesday morning. At about 2 am local time, up to 120 meteors per hour are possible under dark sky conditions. At that time the sky overhead will be pointed toward the densest part of the debris field. True Geminids will appear to radiate from a position above the bright stars Castor and Pollux, but the meteors can appear anywhere in the sky. A bright waxing gibbous moon shining on the peak night will reduce the number of fainter meteors in this year’s shower. But it will set at around 3 am local time, leaving a few hours of prime viewing time.

To see the most meteors during any shower, find a safe, wide-open, dark location, preferably away from the city lights, and just look up with your unaided eyes for a good long while. Binoculars and telescopes are not useful for meteors – their field of view are too narrow. Try not to look at your phone’s bright screen because it’ll ruin your night vision. And keep your eyes heavenward, even while you are chatting with companions. Last year on Insider’s Guide to the Galaxy, we covered meteors and meteorites. It’s on YouTube here.

The Planets

Three bright planets continue to catch our eyes in the southwestern sky after sunset this week – and they’re gathering! They’ll be most tightly spaced – three fist diameters apart – around December 18. For now, extremely bright Venus is positioned about 3.3 fist diameters to the lower right (or 33° to the celestial west) of bright Jupiter – with fainter Saturn between them. Venus’ eastward orbital motion with respect to the background stars will continue until December 18. Meanwhile, the two gas giant planets are being carried west and sunward by Earth’s orbital motion. So the trio of planets will decrease their separation nightly until then.

This week, brilliant Venus will shine low in the south-southwestern sky after sunset, and then set at about 7:20 pm local time. You might need to walk around to find a view of the planet between the trees or buildings after sunset. Venus is still shining near its maximum brightness – a spectacular magnitude –4.66.

Viewed in a telescope, Venus will appear much less than half-illuminated, showing a waning crescent on its sun-facing side. Aim your telescope at Venus as soon as you can spot the planet in the sky (but ensure that the sun has completely disappeared first). That way, the planet will be higher and shining through less distorting atmosphere – giving you a clearer view of it. A brighter sky will also allow Venus’ shape to be seen more readily. The planet will grow in size and wane in phase every week for the rest of this year because Venus will be traveling into the space between Earth and the sun.

Jupiter and Saturn, parked at the opposite ends of the constellation of Capricornus (the Sea-Goat), will become visible a short time after dusk. Look for them shining less than a third of the way up the south-southwestern sky. You’ll need the sky to darken a little more before 18 times fainter Saturn appears. It’s 1.5 fist diameters to Jupiter’s right (or 15.5° to the celestial west). Jupiter and Saturn will set in the west, 90 minutes apart, after mid-evening – so observe each planet as early as you can spot it, while it’s higher. And, don’t dawdle – they’ll become unobservable in telescopes within a few weeks!

Saturn and its beautiful rings are visible in any size of telescope. If your optics are sharp and the air is steady, try to see the Cassini Division, a narrow gap between the outer and inner rings, and a faint belt of dark clouds encircling the planet. Remember to take long, lingering looks through the eyepiece – so that you can catch moments of perfect atmospheric clarity.

From here on Earth, Saturn’s axial tilt of 26.7° lets us see the top of its ring plane, and allows its brighter moons to array themselves all around the planet. Saturn’s largest and brightest moon Titan never wanders more than five times the width of Saturn’s rings from the planet. The much fainter moon named Iapetus can stray up to twelve times the ring width during its 80-day orbit of Saturn. The next brightest moons Rhea, Dione, Tethys, Enceladus, and Mimas all stay within one ring-width of Saturn.

During this week, Titan will migrate counter-clockwise around Saturn, moving from the right (celestial west) of Saturn tonight to the left (celestial east) of Saturn next Sunday. (Remember that your telescope will probably flip the view around.) How many of the moons can you see in your telescope?

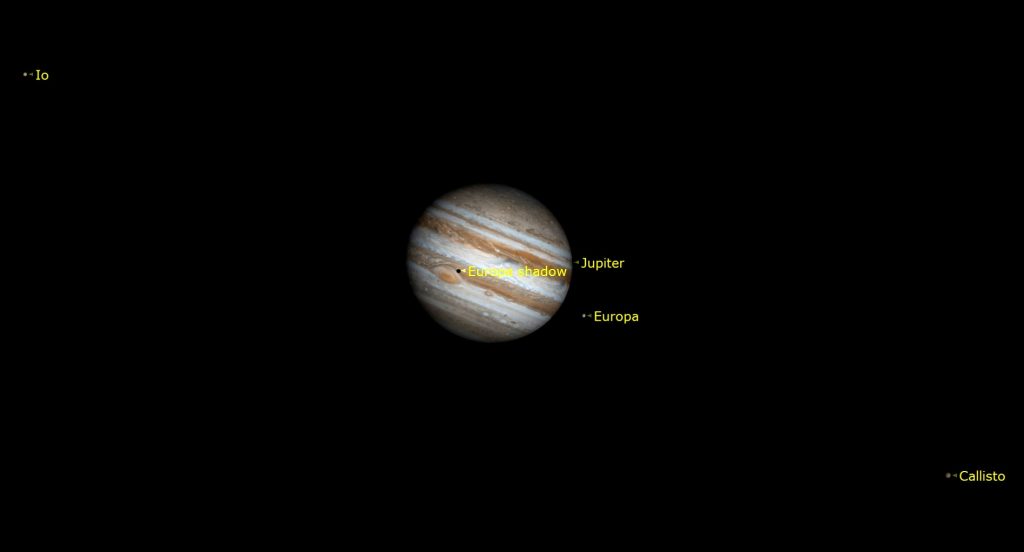

Binoculars and small telescopes will show you the Jupiter’s four large Galilean moons named Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto. Since Jupiter’s axial tilt is a miniscule 3°, those moons always look like beads strung on a line that passes through the planet, and parallel to Jupiter’s dark equatorial belts. That line of moons, and the belts, tilt as Jupiter crosses the sky. The moons’ arrangement varies from night to night. Io, for example, orbits Jupiter once every 42 hours. From one night to the next night, 24 hours has elapsed on Earth – time for Io to complete half an orbit and shift from one side of Jupiter to the other. The other Galilean moons move less rapidly, taking between 3.5 and 16.7 days to orbit Jupiter.

For observers in the Eastern Time Zone with good telescopes, the Great Red Spot (or GRS) will be visible while it crosses Jupiter after dusk on Monday, Wednesday, and Friday (with Europa’s shadow), and in mid-evening tonight (Sunday), on Tuesday, Friday, and next Sunday.

From time to time, the small, round, black shadows cast by Jupiter’s Galilean moons become visible in amateur telescopes when they cross (or transit) the planet’s disk. On Friday evening, December 10 in the Americas, observers with telescopes can watch the small round shadows of two of Jupiter’s moon cross the planet – one of them accompanied by the Great Red Spot! At 5 pm EST (or 22:00 GMT), the shadow of Callisto will be completing a crossing of the planet that began at 18:15 GMT. A few minutes later, the Great Red Spot and the shadow of Europa will rotate into view on the opposite side of Jupiter’s disk. That shadow and the spot will complete their own crossing several hours later, at about 8 pm EST (or 01:00 GMT on December 11).

Distant, dim Neptune is in the evening sky – near the border between Aquarius (the Water-Bearer) and western Pisces (the Fishes). The magnitude 7.9 planet is also 2.4 fist diameters to the upper left (or 24° to the celestial east) of Jupiter. If the sky is very dark, Neptune can be seen in good binoculars. To locate it, find the up-down grouping of five medium-bright stars Psi, Chi, and Phi Aquarii (or ψ, X, and φ Aqr). Neptune’s non-twinkling speck will sit several finger widths to the left (or 3 degrees to the celestial NNE) of the top star, Phi. Viewed in a telescope, Neptune’s apparent disk size will be 2.3 arc-seconds. Your best views will come in mid-evening, when the blue planet is highest in the southern sky.

Uranus is shining at magnitude 5.7. Look for the planet’s small, blue-green dot moving slowly retrograde westwards in southern Aries (the Ram), a fist’s width below (or 11.5 degrees southeast of) that constellation’s brightest stars, Hamal and Sheratan. Or use binoculars to locate Uranus using the nearby star Mu Ceti. Uranus is also about 1.6 fist diameters to the upper right (or 16 degrees to the celestial west-southwest) of the Pleiades star cluster. This week Uranus will be observable all night long – especially around 10 pm local time, when it will have climbed more than halfway up the southeastern sky.

If you are heading out early to see the comet, look for nearby Mars, too! This week Mars will continue its year-long journey to a bright showing at opposition in December, 2022. You might spot the magnitude 1.6 planet shining very low in the east-southeastern sky just after it rises at around 6 am local time, especially if you live at a tropical latitude. Your odds of successfully spotting Mars will improve on each subsequent morning. Take care to turn binoculars and telescopes away from the eastern horizon well before the sun rises.

Mercury will join the western post-sunset sky next week.

Public Astro-Themed Events

Every Monday evening, York University’s Allan I. Carswell Observatory runs an online star party – broadcasting views from four telescopes/cameras, answering viewer questions, and taking requests! Details are here. Their in-person Wednesday night viewing has been converted to online via the observatory YouTube channel.

My free, family-friendly Insider’s Guide to the Galaxy webcasts with Jenna Hinds of RASC National returns on Tuesday, December 7 at 3:30 pm EST, when we’ll cover the biggest events in astronomy during 2022. You can find more details and the schedule of future sessions here.

RASC’s in-person sessions at the David Dunlap Observatory may not be running at the moment, but they are pleased to offer some virtual experiences instead, in partnership with Richmond Hill. The modest fee supports RASC’s education and public outreach efforts at DDO. On Sunday afternoon, December 12 from 12:30 to 1 pm EST, tune in for DDO Sunday Sungazing. Safely observe the sun with RASC, from the comfort of your home! During these family-friendly sessions, a DDO Astronomer will answer your questions about our closest star: the sun! Learn how the sun works and how it affects our home planet. Live-streamed views of the sun through small telescopes will be included, weather permitting. Only one registration per household is required. Deadline to register for this program is Wednesday December 8, 2021 at 3 pm. Prior to the start of the program you will be emailed information on the virtual program links and any specific information relating to your program. The registration link is here.

Don’t forget to take advantage of the astronomy-themed YouTube videos posted by RASC Toronto Centre and RASC Canada.

Keep looking up, and enjoy the sky when you do. I love questions and requests. Send me some!

4 Responses

Will the comet be visible in the midnight sky in Europe (Belgium)? Because of the time difference?

It’s visible at the same time of the morning, regardless of your time zone. That’s why I use the phrase “local time” in such cases.

The exception is that Southern Hemisphere and tropics observers won’t see the comet until the evenings after it passes perigee on Sunday. Good luck seeing it!

I just would like to share what my husband and I had seen on November 18 at 6:45 easter time. We were driving to the Airport in Thunder bay and we say a huge thing crashing from the sky, at first I said to my husband : there a plane crashing, oh my god! It was all in fire. But my husband said no it’s probably a meteorite or a comet… which we don’t know much about those thing. It seems like it was going to crash right in the Superior Lake. Did not heard anything about this. At 6:45 in the morning I am sure we were not the only one who saw this thing in the sky, it was so spectacular and fast…. I was sure it was a plane crashing but obviously it was not.

Hi, Lucie!

It sure sounds like you saw a bolide (or fireball) – an extra-large meteor. How lucky you were. You can check to see whether other preople saw it by visiting a Fireball reporting service such as https://fireball.amsmeteors.org/members/imo_view/browse_reports

On November 18, it could have been an Leonids meteor. That shower peaked that night!