Crow Moon Eclipsed on Thursday Night, Inner Planets Dance at Sunset, and Spots Cross Jupiter!

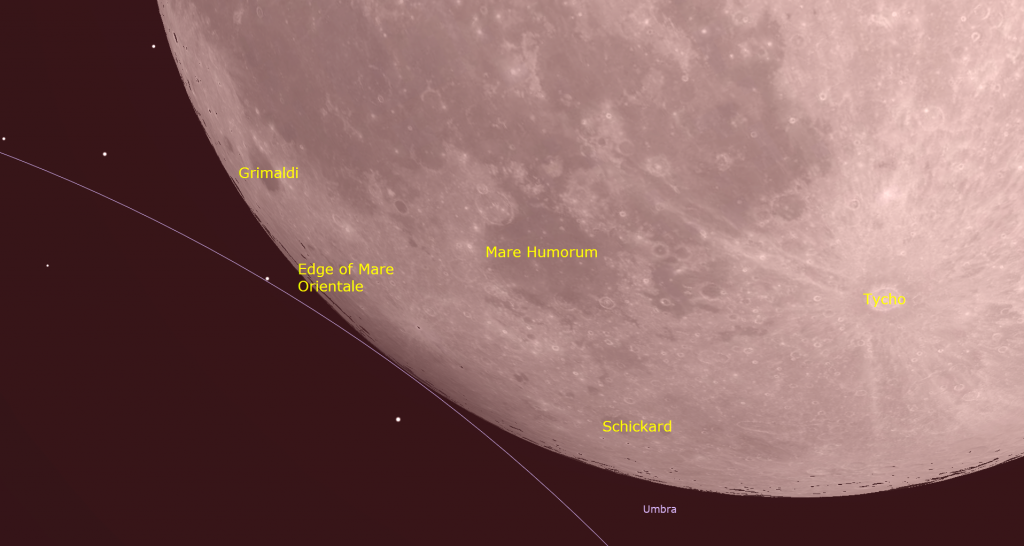

This composite of images of the total lunar eclipse of April 15, 2014 was captured and processed by Michael Watson. The curved shadow on the moon told the ancients, and us today, that the Earth is a sphere.

Hello, Middle of March Stargazers!

Here are your Astronomy Skylights for the week of March 9th, 2025 by Chris Vaughan. Feel free to pass this along to your friends and send me your comments, questions, and suggested topics. You can also follow me on FaceBook, Instagram, Threads, and Bluesky as astrogeoguy! Unless otherwise noted, all times are expressed in Eastern Time. To subscribe to these emails please click this MailChimp link.

If you’d like me to bring my Digital Starlab portable inflatable planetarium to your school or other daytime or evening event in Simcoe, Grey, and Bruce Counties, or deliver a virtual session anywhere, contact me through AstroGeo.ca, and we’ll tour the Universe, or the Earth’s interior, together! My book with John A. Read entitled 110 Things to See With a Telescope is a guide to viewing the deep sky objects in the Messier List – for both beginners and seasoned astronomers. DM me to order a signed copy!

With the clocks changed and the sun setting later, evening stargazing will start later now. The moon will shine brightly all week worldwide. It will produce a nice total lunar eclipse while at its full phase on Thursday night/Friday morning, so I break down all the details around lunar eclipses. The two inner planets will dance together in the west at sunset. Then bright, spotty Jupiter and Mars will remain for most of the night. Read on for your Skylights!

Springing Forward

If you missed last week’s note about Daylight Saving Time (or DST, for short), I posted it here.

The Moon

The moon will brighten night skies worldwide this week while it passes through its full moon phase opposite from the sun. Tonight (Sunday) the already bright, 84%-illuminated waxing gibbous moon will rise during mid-afternoon. Once the sky darkens, bright, reddish Mars and the brightest of the winter stars will sparkle to the moon’s upper right (or celestial west). The moon’s host constellation of Cancer (the Crab) lacks the lustre to compete with such a bright moon.

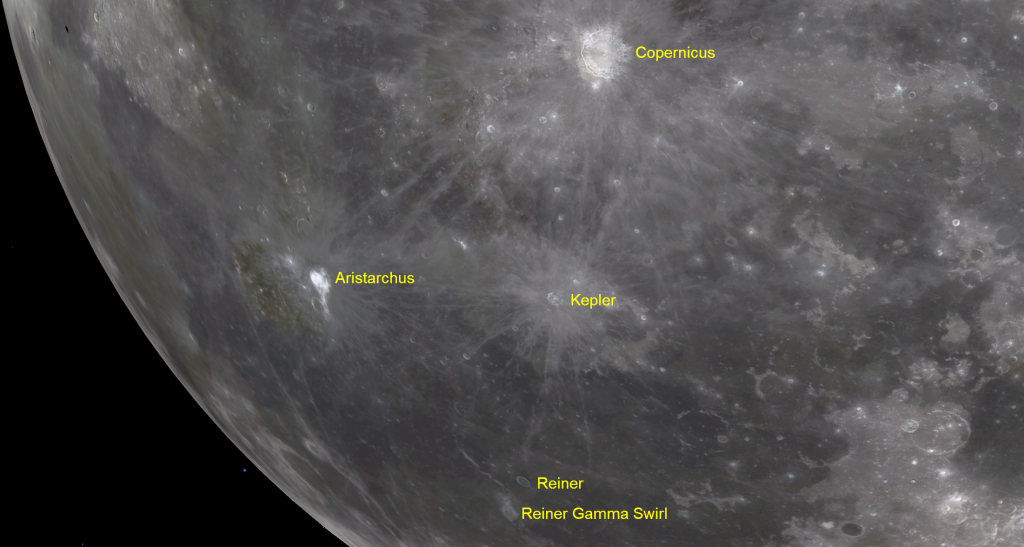

You can still enjoy the spectacle of the moon’s terminator marching across its face and highlighting its rugged terrain until about mid-week. After spending another night with the crustacean, the moon will sweep through Leo (the Lion) from Tuesday through Thursday, posing above the beast’s bright, white heart star, Regulus on Tuesday. By that point in the week, all of the vast expanse of dark Mare Imbrium “the Sea of Rains” and most of enormous Oceanus Procellarum “the Ocean of Storms” below it will be lit up. Tuesday will be a fine night to view the bright little crater Aristarchus. The complex area surrounding it is especially interesting in a backyard telescope.

On Wednesday night, if you direct your focus on the centre of the moon above and between the prominent craters Tycho and Copernicus, you can see the trio of dark stains of volcanic ash within the crater Alphonsus. Pay some attention to the prominent ray systems emanating from Tycho and Copernicus, and other young craters. The rays have both different styles and are not radially symmetrical, telling us about the direction and approach angle that the object that created those craters arrived from. There are lots of ray systems on the moon, if you look for them.

If you aim a telescope at a point about twice the distance from Copernicus to Kepler, you can see one of the moon’s enigmas. The Reiner Gamma Lunar Swirl is a small, high-albedo (i.e., light in colour) area located just inside the western edge of Oceanus Procellarum. It is best seen a night or two after the moon’s full phase every month. The easily-seen, 30 km-diameter crater of Reiner is located a short hop to the upper right (or lunar east-southeast) of Reiner Gamma. The swirl is composed of ancient lunar basalt that has not been darkened by weathering, likely due to protection from cosmic rays by a strong localized magnetic field – the swirl has one of the strongest magnetic anomalies on the moon! At high magnification, its complex, fish-like shape is fascinating.

The moon will reach its full phase on Friday morning, March 14 at 2:55 am EDT or 06:55 Greenwich Mean Time, which converts to 11:55 pm PDT on Thursday. At a glance, the moon will appear full on both Thursday and Friday night. The March full moon, known as the Worm Moon, Crow Moon, Sap Moon or Lenten Moon, always shines in or near the stars of Leo or Virgo. The indigenous Ojibwe people of the Great Lakes region call this full moon Ziissbaakdoke-giizis “Sugar Moon” or Onaabani-giizis, the “Hard Crust on the Snow Moon”. For them it signifies a time to balance their lives and to celebrate the new year. The Cree of North America call it Mikisiwipisim, the “the Eagle Moon” – the month when the eagle returns. The Cherokee call it Anvyi, the “Windy Moon”, when the planting cycle begins anew. This full moon will pass directly through the Earth’s umbral shadow, producing a total lunar eclipse visible across the Americas and a partial eclipse in the Pacific and western Europe and Africa regions. Read the next section for lots of details about that.

After Friday morning’s eclipse, the waning gibbous moon will glide through the large constellation of Virgo (the Maiden). On Saturday after dusk, it will shine above Virgo’s brightest star Spica all night long and then bid us farewell over the western horizon on Sunday morning. Late on Sunday evening, the moon will rise below Spica. Watch for Arcturus, one of the skies brightest stars, shining low in the eastern evening sky at this time of year.

Thursday Night’s Total Lunar Eclipse

Because the Earth is a solid sphere with sunlight shining on it, it casts a circular shadow into space that is opposite from the sun and close to the ecliptic. That black shadow is invisible against the black sky, but if an object, such as the International Space Station or the moon, passes through it, Earth’s solid bulk will prevent the sunlight from reaching the object, and darken it. If you watch satellites on a clear, dark night, and note where in the sky they disappear (entering Earth’s shadow) or suddenly appear (exiting Earth’s shadow), you can trace out Earth’s shadow. It’s always there!

The zone where the sun is completely obscured by the Earth is called the umbra (that’s where the word “umbrella” – a sun shade – comes from). Surrounding this is a circle of twice that size called the penumbra, where some portion of the sun can still shine on an object. Objects passing through the penumbra will appear a bit darkened, but still visible, for those of us on Earth.

The diameter of Earth’s shadow decreases as you move farther from Earth. At the moon’s distance, the umbra is about 1.3 degrees (or a thumb’s width) in diameter. That’s almost three times the width of the moon. (The diameter of Earth’s shadow is too small at the distance that Mars orbits to produce an eclipse of that, or any other, planet.)

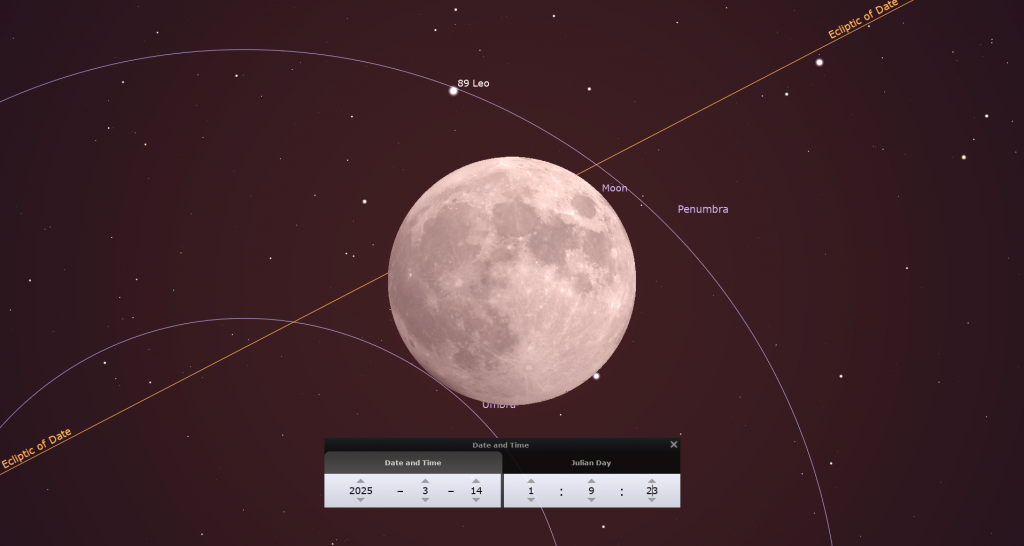

The moon’s orbit is tilted by about 5 degrees compared to the ecliptic. That allows the moon to cross the ecliptic from time to time, and to veer to the north and south of the ecliptic by almost a palm’s width. Full moons occur every lunar month when the sun, Earth, and moon align with Earth between the sun and the moon. New moons occur when they align with the moon between Earth and the sun. These alignments, or syzygys, of the sun, Earth, and moon happen 2 to 5 times per year – of which half are lunar eclipses and the rest are solar eclipses.

We experience a lunar eclipse whenever a full moon phase occurs at the same time that the moon is close enough to the ecliptic for it to dip fully or partially into Earth’s shadow. If the moon completely enters the umbra, we see a total lunar eclipse. If a part of the moon only enters the penumbra and avoids the umbra, we see a partial lunar eclipse. If the moon only passes through the penumbra, we see a very subtle penumbral lunar eclipse. Total eclipses are the rarest of three types. Lunar eclipses are visible simultaneously by everyone on Earth for whom the moon is above the horizon, or about half of the world.

The moon switches between its full and new phases in only two weeks (or 14.75 days, to be exact). The moon is generally still near the ecliptic during that interval, so lunar and solar eclipses tend to occur in pairs two weeks apart. Because solar eclipses require you to be in a specific place on Earth, many of those ones are only visible for observers located near the Arctic or Antarctica. This lunar eclipse will be followed by a partial solar eclipse that will sweep over the North Pole on Saturday morning, March 29. (Sometimes, the solar eclipse precedes the corresponding lunar eclipse.)

Solar eclipses require special filters to protect your eyes from the exposed sun, but all lunar eclipses are completely safe to look at with unprotected eyes and through binoculars and telescopes – and to photograph. A telescope can even reveal the Earth’s shadow creeping across the moon’s surface in real time.

Earth’s atmosphere refracts (or bends) rays of sunlight because it slows the light down a little. While the opaque solid Earth completely prevents sunlight from reaching anything behind it, atmospheric refraction allows the sunlight that passes through Earth’s thin blanket of air to bend around the Earth’s horizon, letting some light reach even a fully eclipsed moon. The extra-long trip that sunlight must take through our air preferentially scatters away the shorter, bluer wavelengths, leaving the longer wavelength light to turn the eclipsed moon reddish with sunset-coloured light – hence the nickname “blood moon”. If you could view the Earth from the surface of the moon during a total lunar eclipse, it would appear as a dark disk encircled by a beautiful, thin ring of reddish light!

The moon moves east in its orbit by about its own diameter every hour. If the moon travels through the full width of Earth’s shadow, the lunar eclipse will last almost five hours from “first bite” to “last bite”. If the moon merely dips its northern or southern pole into the umbral shadow, the resulting partial eclipse can last only a few minutes. Everything in between those ranges is possible. If the full moon is “super”, i.e., extra close to Earth and larger in diameter, its total eclipse will be shortened. A small full moon at apogee will fit within the shadow for a longer time.

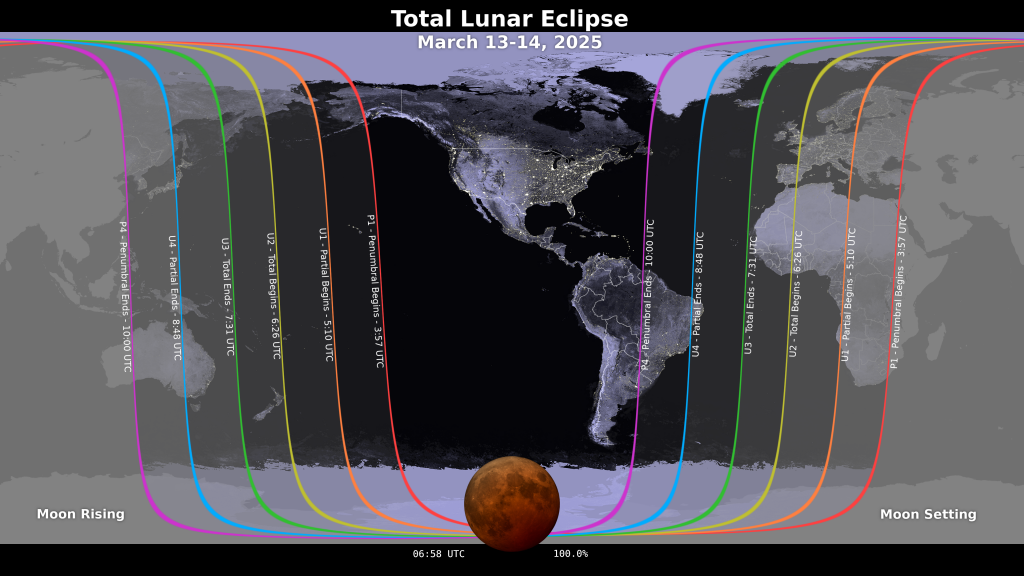

All of this eclipse will be visible across North and South America and most of the Pacific Ocean. None of this eclipse will be visible from eastern Africa and Europe, Asia, and western Australia. The regions between those zones will see the eclipse in progress while the moon is rising or setting.

Timing-wise, this eclipse will be a mixed bag for observers in the Americas. For folks living in the Central Time zone and farther east, the entire eclipse will happen during the wee hours of Friday morning. For those viewing it from farther west, it will start in late evening on Thursday and finish after midnight on Friday morning. This will be the first of two total lunar eclipses for 2025. The second one will be a pre-dawn total eclipse on September 8 that is only visible across Asia.

If you can tolerate the late night hour, and have clear skies, this could be one the best lunar eclipses you’ll ever see from home! Unfortunately, as I write this, the weather forecast for Southern Ontario is cloudy on Thursday night. If the clouds aren’t too thick, you’ll still be able to glimpse the shape of the eclipsed moon.

This lunar eclipse will feature a mini full moon only crossing through the northern half of Earth’s umbra shadow. Let’s look at the timing for it.

The lower left (southwestern) rim of the full moon will start its trip through the weaker penumbral shadow at 11:57 pm EDT or 8:57 pm PDT on Thursday evening, very slightly darkening the leading, right-hand edge of the moon. The first noticeable “bite” out the moon will appear when it contacts the central umbra at 1:09:23 am EDT on Friday morning. That’s a comfy 10:09:23 pm PDT on Thursday evening for those out west. For those viewing the first bite through a telescope, my favorite part, aim your telescope at the edge of the moon nearest to Mare Humorum. I’ll share a picture of that.

The moon will be fully eclipsed into a reddened, so-called “Blood Moon” between 2:26 am and 3:32 am EDT (or 11:26 pm to 12:32 am PDT). At greatest eclipse at 3:00 am EDT or 12 midnight PDT, the moon’s northern edge will be close to the edge of Earth’s umbra, causing the southern part of the moon to look noticeably darker than the northern part. At 3:32 am EDT, the moon will start to exit the umbra and gradually refill with light. The moon will completely exit the Earth’s umbral shadow at the final “bite” time of Friday morning at 4:48 am EDT or 1:48 am PDT, but it will still be partially darkened by the Earth’s penumbral shadow until 6 am EDT or 3 am PDT.

During maximum eclipse, fainter stars and objects around the dimmed full moon will return to visibility. Amateur astronomers might want to test whether they can catch sight of some spring galaxies like the Leo Triplet and Markarian’s Chain in their telescope.

You do not need to drive to a special site to see this eclipse, but you will want to ensure that the moon won’t be blocked by buildings or trees, especially if you plan to photograph all stages of the event. In the Greater Toronto Area, the moon will be more than halfway up the southern sky when the partial phase begins, due southwest at maximum eclipse, and only one-third of the way up the west-southwestern sky at the end of partiality. Let me know if you see it!

Details for any lunar or solar eclipse can be found at Fred Espenak’s terrific Eclipsewise.com site. His page for this eclipse is here. The Virtual Telescope Project, featuring live views of the eclipse from some of my friends’ cameras, will start here at midnight Eastern Time (or 9 pm PDT) on Thursday night. Timeanddate.com will have a stream available here, too.

Try to catch this eclipse if your weather allows for it. The next total lunar eclipse for Canada will not be until March 3, 2026, when we’ll see another pre-dawn event with totality lasting from 4:49 am to 6:52 am Eastern Time.

The Planets

Three other planets will remain available after Mercury and Venus set. Very bright, white Jupiter will become visible high in the southwestern sky at sunset. Jupiter will descend the western sky and then set around 2:20 am local time. Jupiter will continue to shine above Taurus’ brightest star, reddish Aldebaran, which marks the eye of the bull. Just a friendly head’s up that we only have about six weeks remaining in which to view Jupiter in a telescope. The number of hours each day is also diminishing as the later sunsets delay darkness.

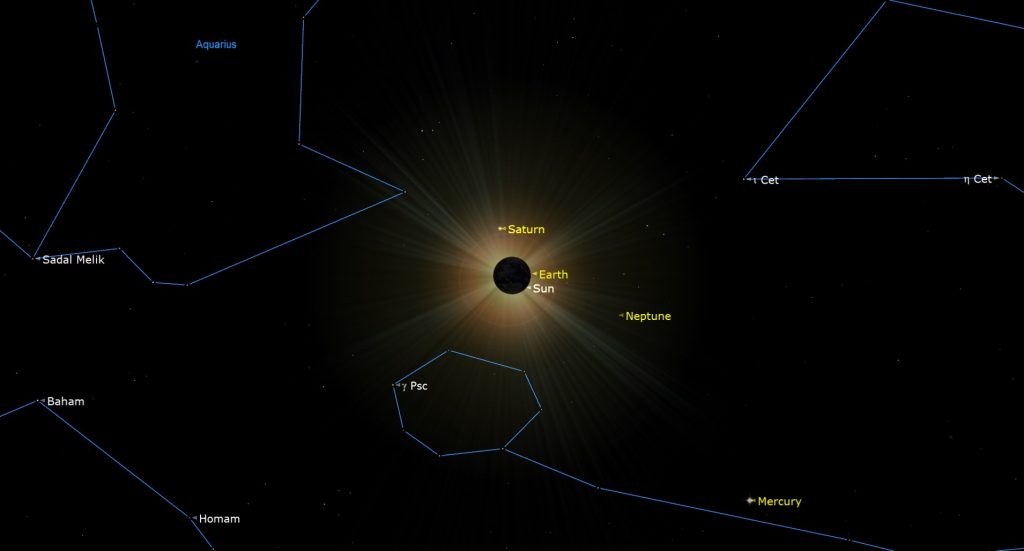

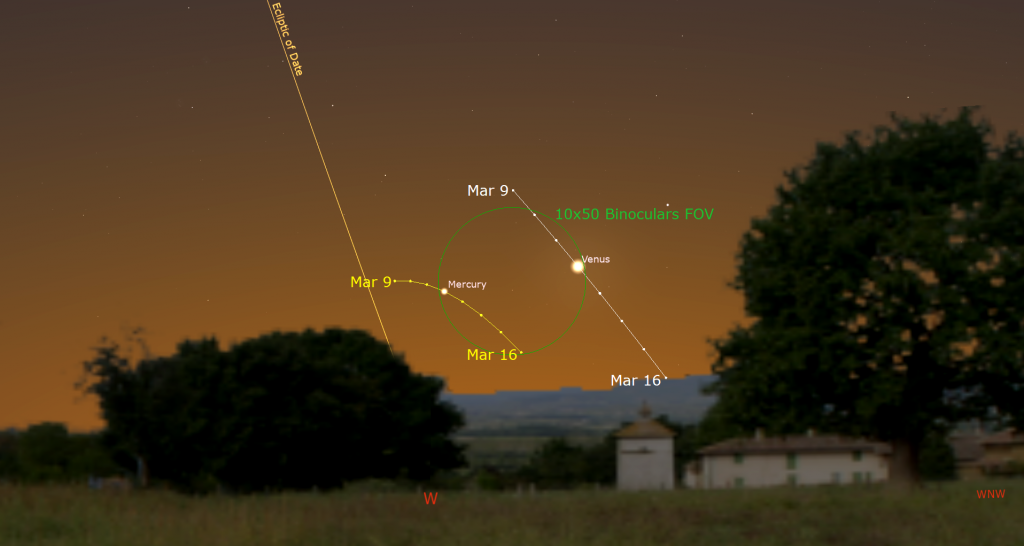

The inner planets Mercury and Venus will be dancing with one another in the western sky after sunset this week. Both planets will be swinging sunward in their orbits and dropping lower night over night, so make your attempt to see them sooner than later, weather permitting. Mercury, and much brighter Venus to its right, will be cozy enough to share the view in binoculars all week. At closest approach on Wednesday evening, they will be a palm’s width (or 5.5°) apart. Strong binoculars or any backyard telescope will show that Venus has a very slim, 5%-illuminated crescent phase, while Mercury will appear about seven times smaller and a heftier, 26%-illuminated. Both planets will hit the treetops around 8 pm local time and set about 45 minutes later. Wait until the sun has completely disappeared from sight before using any optical aids above the western horizon.

Viewed in any size of telescope, Jupiter will display a large disk striped with dark brow belts and creamy light zones, both aligned parallel to its equator. With a better grade of optics, Jupiter’s Great Red Spot, a cyclonic storm that has raged for hundreds of years, becomes visible for several hours when it crosses the planet every 2nd or 3rd night. For observers in the Americas, that GRS will cross Jupiter’s disk during early evening on Tuesday, Thursday, and next Sunday, and also around midnight Eastern time on Monday, Wednesday, and Saturday night. If you have any coloured filters or nebula filters for your telescope, try enhancing the spot with them.

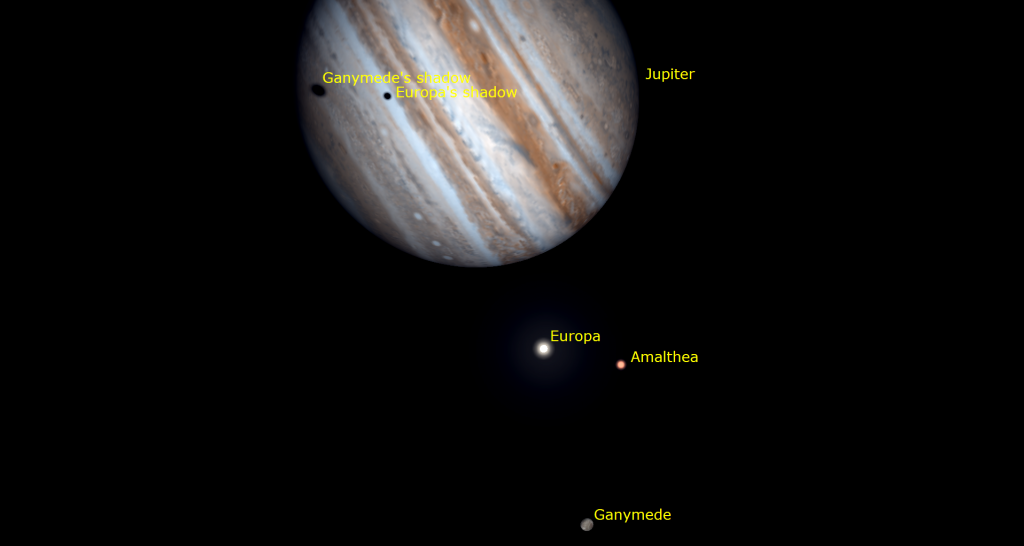

Any size of binoculars will show you Jupiter’s four Galilean moons named Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto lined up beside the planet. Those moons complete orbits of the planet every 1.7, 3.6, 7.2, and 16.7 days, respectively. If you see fewer than four moons, then one or more of them is crossing in front of or behind Jupiter, or hiding in Jupiter’s dark shadow – or two of the moons are very close together, or one moon is eclipsing or occulting another one. All four moons will gather to one side of the planet on Monday night, and will clump up in pairs or trios several times during this week.

From time to time, observers with good quality telescopes can watch the black shadows of the Galilean moons travel across Jupiter’s disk. In the Americas, sky-watchers located in the Americas can watch two shadows cross the southern hemisphere of Jupiter together for about two hours on Tuesday evening, March 11. At 10:42 pm Eastern Time (or 02:42 GMT on Wednesday), the large shadow of Ganymede will join the smaller shadow of Europa, which began its own crossing of the planet half an hour earlier. Both shadows will leave Jupiter in rapid succession starting at 12:46 am EDT (or 04:46 GMT on Wednesday). Io’s small shadow will cross Jupiter on Wednesday evening, March 12 between 7:26 pm and 9:36 pm EDT (or 23:26 to 01:36 GMT on Wednesday-Thursday). Additional shadow crossings will be visible in other time zones.

I skipped over much fainter Uranus because you will not be able to see distant ice giant planet easily with so much moonlight this week. Uranus is spending this year located a palm’s width below the Pleiades Star Cluster in Taurus (the Bull).

The medium-bright, reddish dot of Mars will shine high in the southern sky after dusk, where it will form a triangle to the lower right (or celestial southwest) of Gemini’s bright stars Pollux and Castor. Mars will be highest due south at 9:15 pm local time and set in the west by 5 am local time. Our 140 million km distance from Mars is increasing every night, so the planet is shrinking in size and losing its brilliance. Your good quality backyard telescope might still show its bright polar cap and some dark patches on its small reddish globe. We can continue to see Mars as a bright dot until late July, but do your close-up viewing now.

Public Astronomy-Themed Events

Every Monday evening, York University’s Allan I. Carswell Observatory runs an online star party – broadcasting views from four telescopes/cameras, answering viewer questions, and taking requests! Details are here. They host in-person viewing on the first clear Wednesday night each month. Other Wednesdays they stream views online via the observatory YouTube channel. Details are here.

It’s March Break week in Ontario! Many astronomy-focused groups are presenting family-friendly space and planets events in the GTA. Some are focused on the April 8 solar eclipse. You can view a list of the RASC Toronto Centre events at https://rascto.ca/events.

I’ll be setting up my portable planetarium at Grey Highlands Public Library in Markdale, Ontario and at Pretty River Academy in Collingwood.

On Saturday, March 15 from 10 am to noon, RASC Toronto Centre will host “Sun Fun!” at the David Dunlap Observatory for visitors aged 5 and up. RASC Astronomers will host an interactive session where participants will see live and pre-recorded telescope views of the solar surface, learn about our nearest star, and practice safe solar observing by making their own pinhole projector. This program runs rain or shine. Details and the link for tickets is available at ActiveRH.

On Saturday, March 16 from 7 to 9 pm, RASC Toronto Centre will host Family Night at the David Dunlap Observatory for visitors aged 7 and up. You will tour the sky, visit the giant 74” telescope, and view celestial sights through telescopes if the sky is clear. This program runs rain or shine. Details and the link for tickets is ActiveRH.

Keep your eye on the skies! I love getting questions and requests. Send me some!

2 Responses

I enjoy your articles, but I am having trouble reading the gray-on-white text.

Several studies have examined the impact of text and background color combinations on readability and eye strain. Research indicates that black text on a white background is generally the most readable and preferred combination. For instance, a study highlighted by the Ecological Society of America found that “the most readable color combination is black text on white background; overall, there is a stronger preference for any combination containing black.”

Using gray text on a white background can reduce readability, especially if the gray is too light, leading to eye strain. An article from UX Movement advises that gray text should not exceed 46% brightness to maintain adequate contrast and readability, stating that “if you make your gray text too light, users will have trouble reading it.”

These findings suggest that while some may find high contrast (black on white) harsh, reducing contrast by using lighter gray text can adversely affect readability and increase eye strain.

Aside from this, please “keep on keepin’ on.”

Thanks, Eric!

The text style is tied into the WordPress theme I had to pick in order to show the photos properly. I’m investigating other styles, though. You might want to read the text from the email that I send out on Sundays and use the website version to see the pictures.