Cygnus Soars on High in Moonless Evening, Planets all Night Long, plus Meteors, a Morning Comet, and Zodiacal Light!

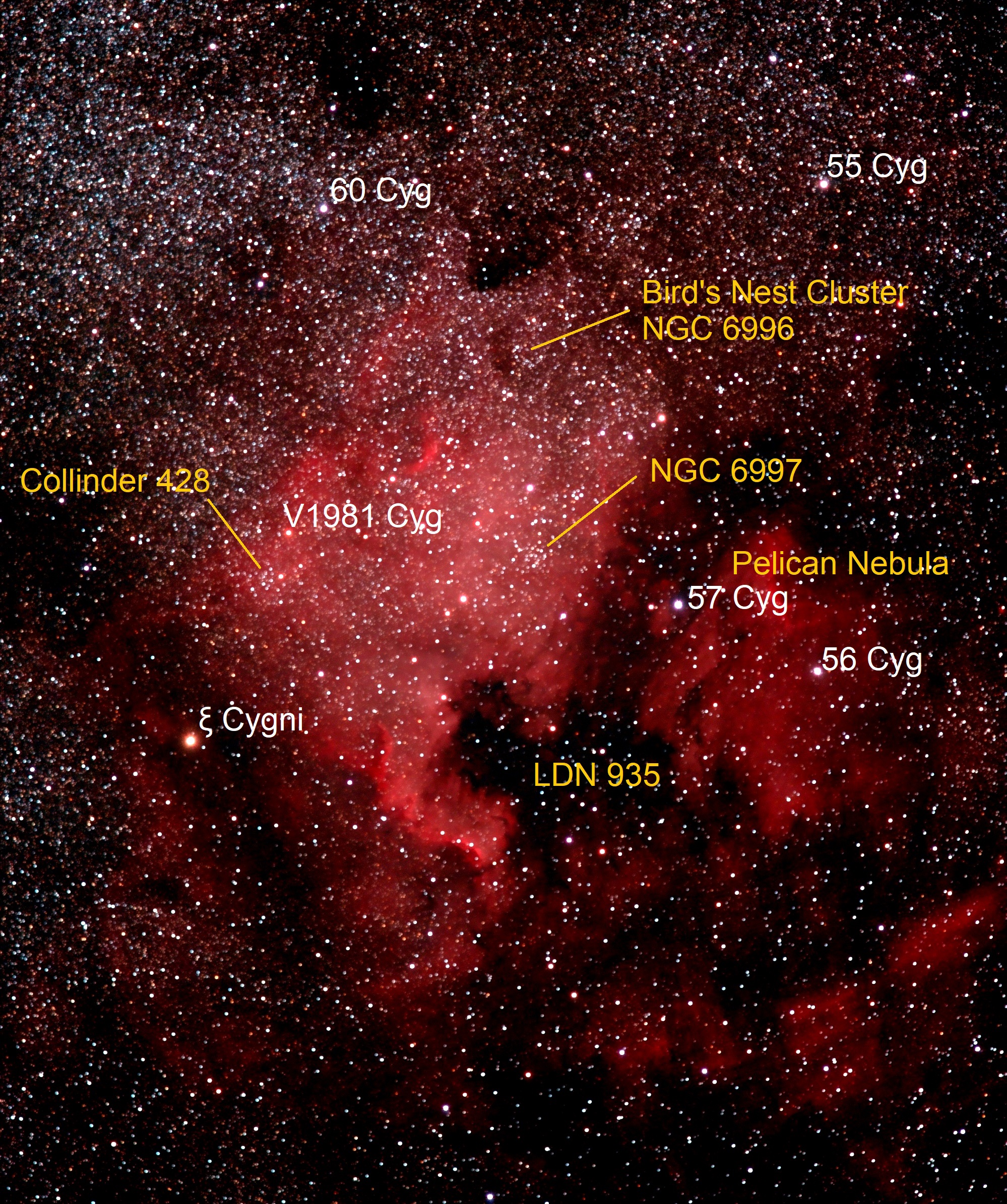

This image of the North American Nebula was captured in 2018 near Thornbury, Ontario by my friend Sailu Nemana. Several of the surrounding bright stars and star clusters within it are highlighted. The Pelican Nebula (at right) is formed by the dark dust of LDN 935. The re/pink colour is produced by ionized hydrogen gas. This photograph spans almost a palm’s width, top to bottom. The nebula will sit near the very bright star Deneb, which will shine nearly overhead in evening.

Hello, October Stargazers!

Here are your Astronomy Skylights for the week of September 29th, 2024 by Chris Vaughan. Feel free to pass this along to your friends and send me your comments, questions, and suggested topics. You can also follow me on Twitter as @astrogeoguy! Unless otherwise noted, all times are expressed in Eastern Time. To subscribe to these emails please click this MailChimp link.

If you’d like me to bring my Digital Starlab portable inflatable planetarium to your school or other daytime or evening event in Simcoe, Grey, and Bruce Counties, or deliver a virtual session anywhere, contact me through AstroGeo.ca, and we’ll tour the Universe, or the Earth’s interior, together! My book with John A. Read entitled 110 Things to See With a Telescope is a guide to viewing the deep sky objects in the Messier List – for both beginners and seasoned astronomers. DM me to order a signed copy!

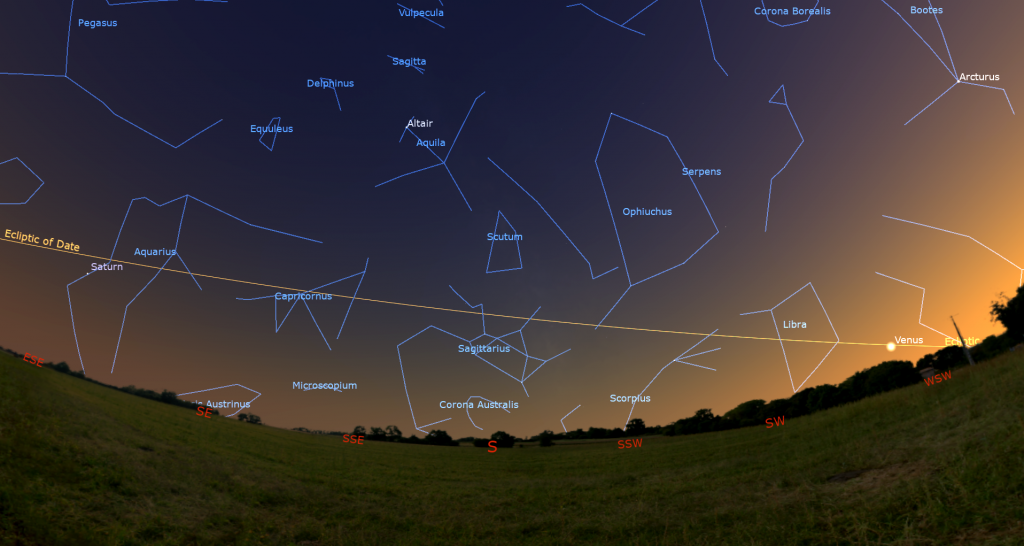

The moon will pass the sun on Wednesday, triggering an annular solar eclipse in the South Pacific, so it will be absent from the night sky this week. The missing moon will allow us to enjoy the sights of Cygnus and a few meteors in evening. Comet Tsuchinshan-ATLAS has brightened dramatically in the pre-dawn sky, where the zodiacal light is glowing, and we have six planets to see from sunset to sunrise. Read on for your Skylights!

Meteor Watch

Keep an eye out for shooting stars. As fall begins we are entering a period of increasing meteor shower activity. Two showers have recently started to ramp up. The Orionids will build to a peak on October 20-21, and the Southern Taurids will grow to maximum on November 4-5. In both cases the meteors will appear to radiate from the eastern sky, where those two constellations will rise late at night.

Comet Tsuchinshan Update

My astronomer friends have been getting up early to try to see and/or image a comet named C/2023 A3 (Tsuchinshan-ATLAS). The comet, which I provided some background on last week, has been mentioned on social media and news sites as a potential bright comet to see in late September-early October. There are always a few comets around, but most of them are too faint to see without a telescope. And, even then, they only look like small, fuzzy stars. This one seems to be worth the effort to set the alarm!

Near perihelion, a comet’s minimum distance from the sun, the increase in solar warming causes it to eject more gas and dust – brightening it and boosting its tail. This comet passes perihelion last Friday, September 27. Now it will move closer to Earth as it departs the solar system again, making it look larger and brighter for us. Over the next two weeks another phenomenon called forward scattering may make the comet look much brighter – potentially bright enough to see in daylight, if you know where to look!

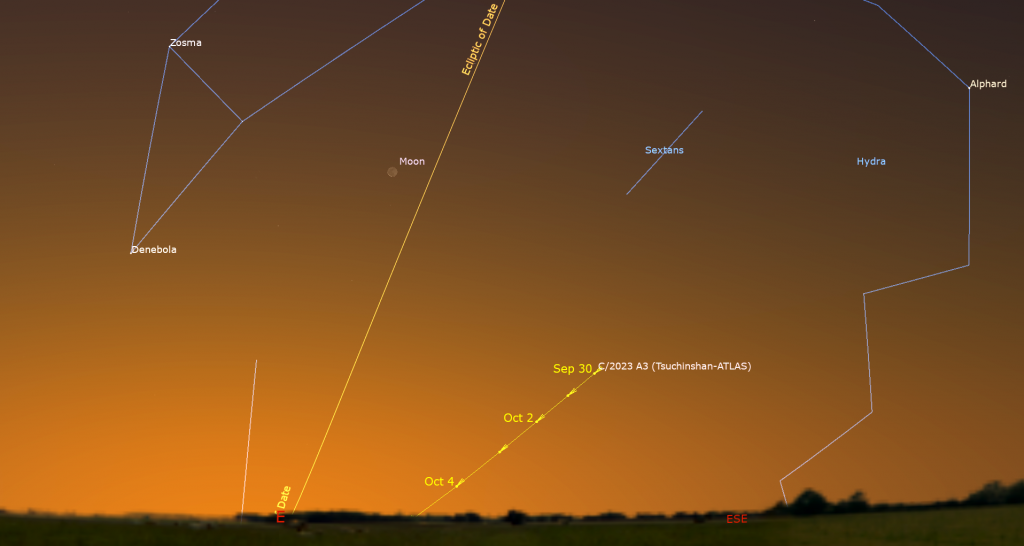

Recent reports are that Comet Tsuchinshan-ATLAS has reached a magnitude value of 2.8, which is within the range of unaided eyes in a clear sky and easy to see in binoculars or telescope. But there’s a bit of a catch. From the perspective of Earth, the comet is still approaching the morning sun in the eastern pre-dawn sky, so it will brighten daily as it gets closer to us, but it will also compete more and more with the morning twilight before sunrise. The early part of this week will be our best chance to see it before it passes the sun on October 9. After that it will be rapidly climbing away from the sun in the western sky after sunset, making the evenings after October 11 another good bet to see it, even though it will be shrinking each day.

From mid-northern latitudes, you can try to see the comet just above the east-southeastern horizon this week. Start looking soon after it rises at about 6 am local time. It will be positioned about a palm’s width (or 6°) to the right of where the sun will rise. The long slender tail will stretch to the upper right, away from the sun. On Monday morning the comet will be positioned about a 1.4 fist diameters to the lower right of the waning crescent moon. On Tuesday the comet will be a fist’s diameter to the moon’s right. From Wednesday on the moon will be gone. Jason L Dain of Halifax, NS posted a terrific photo of the comet taken this morning (Sunday) here.

Be sure to turn all of your optics away from the eastern horizon before the sun rises. Good luck!

Zodiacal Light Alert

During autumn at mid-northern latitudes every year, the ecliptic extends nearly vertically upward from the eastern horizon before dawn. That geometry favors the appearance of the faint zodiacal light in the eastern sky for about half an hour before dawn on moonless mornings. Zodiacal light is sunlight scattered by interplanetary particles that are concentrated in the plane of the solar system – the same material that produces meteor showers. It is more readily seen in areas free of urban light pollution.

Between now until the full moon on September 17, look for a broad wedge of faint light extending upwards from the eastern horizon and centered on the ecliptic. It will be strongest in the lower third of the sky around the bright star Regulus in Leo (the Lion). Don’t confuse the zodiacal light with the Milky Way, which is positioned nearby in the southeastern sky. The zodiacal light and Comet Tsuchinshan-ATLAS will make a nice double feature!

The Moon

For stargazers worldwide, the moon will not be a concern this week. Earth’s natural night light will be hanging out near the sun until next week.

Early risers on Monday can see the moon’s slender crescent shining in the eastern sky. If you head out before the sky begins to brighten, the prominent stars of Leo (the Lion) will sparkle to its upper left. The lion’s head will point upwards and its rear-end, marked by the triangle of stars named Zosma, Chertan, and Denebola, will be lower. With all of the stars rising 4 minutes earlier with every passing day, the beast is making its month-long trek towards its appearance in evening after a visit by the sun in September. It’ll rise before midnight at the end of November, and will dominate the eastern evening sky from mid-winter onward.

As I mentioned above, the moon, and (hopefully) Comet Tsuchinshan-ATLAS, will be visible just before sunrise on Monday. On Tuesday, the old moon will be even slimmer and lower in the east, joining the sun within Virgo (the Maiden). That will be our last glimpse of the morning moon.

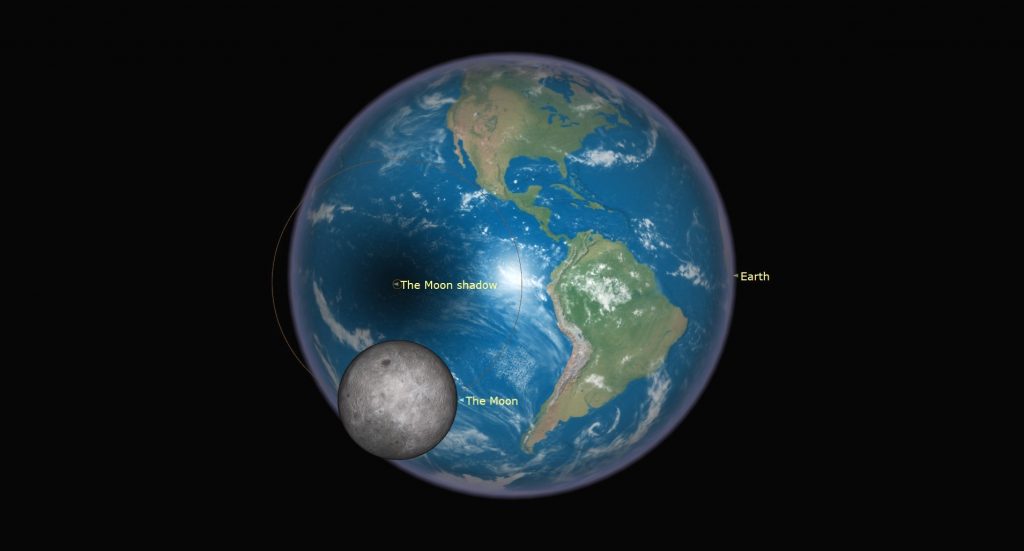

When the moon passes the sun at new moon on Wednesday, October 2 at 2:49 pm EDT, 11:49 am PDT, or 18:49 Greenwich Mean Time, it will generate a solar eclipse visible in the eastern and southern Pacific Ocean region. Since the moon will reach its maximum distance from Earth (or apogee) only an hour after that, it will be farther from the Earth and too small to completely block the sun’s disk, resulting in an annular, or “ring of fire”, solar eclipse.

The narrow track where annularity will be visible will begin about 1,700 km south of the Hawaiian Islands at 16:54 GMT or 7:54 am Hawaiian time. From there, the moon’s shadow will rapidly sweep southeast across the ocean, reaching greatest eclipse, with 7.4 minutes of annularity, at 18:45 GMT, and then 6.4 minutes of annularity on Rapa Nui (Easter Island) at 2:07 pm EASST or 19:07 GMT. The eclipse will reach the mountainous Patagonian coast of Chile at or 5:22 pm CLST or 20:22 GMT, then the eastern coast of Argentina six minutes later at 20:28 GMT. The eclipse will end 550 km north of South Georgia Island at 20:36 GMT.

A broad region surrounding the annularity track will see a partial solar eclipse, but no part of the eclipse will be visible from continental North America. Exact times for your location can be obtained from astronomy apps like Stellarium and StarWalk 2, or you can look at the detailed material, including coverage maps, complied by astronomical treasure Fred Espenak at his website page https://www.eclipsewise.com/solar/SEprime/2001-2100/SE2024Oct02Aprime.html. Many channels will livestream the eclipse. Proper protective solar filters will be required to view any part of a solar eclipse.

The young crescent moon will appear above the southwestern horizon after sunset from Wednesday onward, but it will be several degrees below the shallow sloping ecliptic and therefore too low to be easily seen until about Saturday. That evening, for a short period after sunset, the moon will shine several finger widths to the lower left (or celestial south) of the very bright planet Venus in Libra (the Scales). The duo will be cozy enough to share the view in binoculars, but wait until the sun has completely set before using them. On Sunday evening, the moon’s eastward orbital motion will place it more than a fist’s diameter to Venus’ left, and a little higher, making it easier to see. Venus is farther from Earth than the sun, so it will show a gibbous phase in a telescope, in contrast to the crescent moon.

This coming weekend, watch for Earthshine on the moon, also known as the Ashen Glow and “the old moon in the new moon’s arms”. That’s sunlight reflected off Earth and back onto the moon, slightly brightening the dark portion of the moon’s Earth-facing hemisphere. The phenomenon appears for several days before and after each new moon. Since the Earthshine light has made an extra round trip from Earth to the moon and back, it is about 2.6 seconds “older” that then the light we see from the lit crescent!

The Planets

The planets bonanza continues this week. From now until February, we’ll have six planets to view – four in the evening, and two more from late-night to dawn. Only sun-bound Mercury will be absent over the next while – but it, too, will pop out from time to time. Now’s the time to get that telescope if planets are your favourite!

If you have cloud-free, unobstructed view towards the western horizon, you can look for the brilliant planet Venus shining over the horizon for a short time after sunset. This week at mid-northern latitudes the planet will set around 8 pm local time, about an hour after the sun. The planet has been gradually increasing its distance from the sun every day, but the shallow angle of the ecliptic has kept the planet shining very low in the western sky. Search about two fist diameters to the left of where the sun went down. If you see something bright that is moving left or right, it’s an airplane. Venus will be higher and easier to see for folks living closer to the tropics. It will be safe to use binoculars or a telescope on it after the sun has completely disappeared. In a telescope the planet will show a “swimming” (due to the extra air you are looking through) 85%-illuminated disk. Venus and Mercury both show phases like the moon since they are closer to the sun than we are.

Meanwhile, over in the southeastern sky, the medium-bright yellowish dot of Saturn will be climbing higher while Venus drops. The ringed planet will cross the sky all night long, and set in the west before dawn. You’ll get the clearest views of Saturn in a telescope when it’s higher in the sky after 8 pm. The faint stars of Aquarius (the Water-Bearer) will be arranged to the right of Saturn. Binoculars will show you a bent-line trio of stars named Psi Aquarii sparkling to Saturn’s lower left. See if you can tell that the lower two are white, while the higher one is golden. Two redder stars named Phi and Chi Aquarii will appear to Saturn’s left and lower left, respectively.

Saturn’s rings effectively disappear when they become edge-on to Earth every 15 years. They will do that next March, so they already appear as a thick line drawn through the planet. Good binoculars can hint that Saturn has rings, but any size of telescope will show the rings and that Saturn has moons. In most years, Saturn’s moons are spread all around the planet – unlike Jupiter’s Galileans moons, which are always in a line – but Earth’s perspective of the Saturn system this year and next year is making its moons line up with the rings.

Saturn’s largest and brightest moon Titan never wanders more than five times the width of Saturn’s rings from the planet. The much fainter moon named Iapetus “eye-YA-pet-us” can stray up to twelve times the ring width during its 80-day orbit of Saturn. The next brightest moons Rhea “REE-ya”, Dione “Dee-OWN-ee”, Tethys “Teth-EES”, Enceladus “En-SELL-a-dus”, and Mimas “MY-mass” all stay within one ring-width of Saturn. You may be surprised at how many of those six you can see through your telescope if you look closely when the sky is dark and calm.

During this week, Titan will move from far to Saturn’s lower left (or celestial east of it) tonight, pose closely below Saturn on Thursday, and then stretch far to the upper right of Saturn (or celestial west) on the coming weekend. (Remember that your telescope will probably flip the view around.) The rest of the moons will be tiny specks in a line beyond the rings.

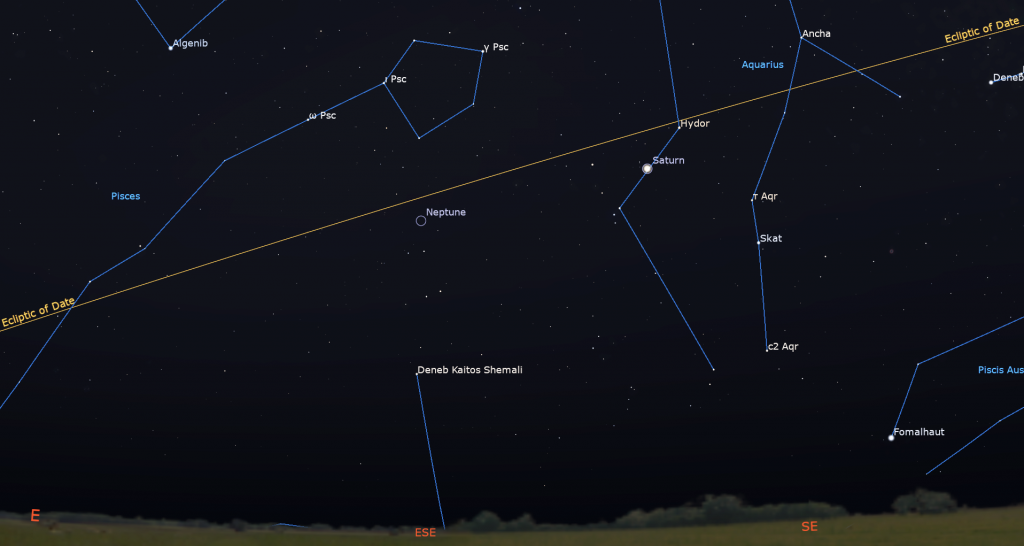

Earth’s perspective of the Saturn system will also cause Saturn’s moons and their small black shadows to frequently cross its disk – but you’ll need a very high quality telescope to watch those. Saturn is being chased across the sky every night by the distant blue planet Neptune – but that planet requires a big pair of binoculars or a telescope to see it. This week Neptune will rise after sunset and be visible all night long – especially while it’s higher up after about 8:30 pm local time.

Slow-moving Neptune will spend all of this year in western Pisces (the Fishes). During evening it’s about 1.4 fist widths to the lower left (or 14° to the celestial ENE) of Saturn and a palm’s width below the circle of stars that forms Pisces’ western fish. Use binoculars to find the upright rectangle formed by the medium-bright stars 27, 29, 30, and 33 Piscium. Neptune will be the bluish, dull “star” sitting about two finger widths above (or 2° celestial north of) that box.

Blue-green Uranus will rise in the east around 8:45 pm local time, and then cross the sky all night long near the bright little Pleiades star cluster in Taurus (the Bull), which will be sparkling about a palm’s width to Uranus’ upper left. The slow-moving, distant planet will remain near the Pleiades until 2027! Uranus will become high enough for viewing in binoculars or a backyard telescope after 11 pm, but that time will be earlier every week. To get you in the ball-park, look for the bright star Menkar shining 2.2 fist diameters to the right of the Pleiades. Uranus will be on the line joining the bottom star of the Pleiades to Menkar.

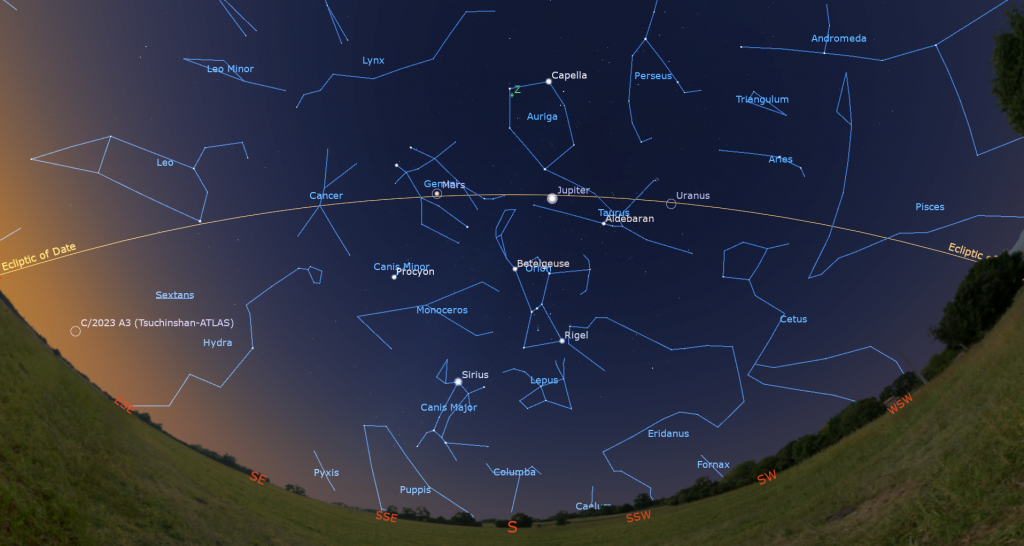

With brighter Venus setting so early, Jupiter will be the planet to catch your eye every night after it clears the rooftops in the east around 11:30 pm local time. (Like Uranus, it, too, will appear about 30 minutes earlier every week.) Jupiter’s brilliant white dot will climb to very high in the southern sky by sunrise. The king of the planets will wander between the horns of Taurus (the Bull) for the next few months while positioned about a fist’s width to the left (or 12° to the celestial ENE) of the bull’s brightest star, reddish Aldebaran.

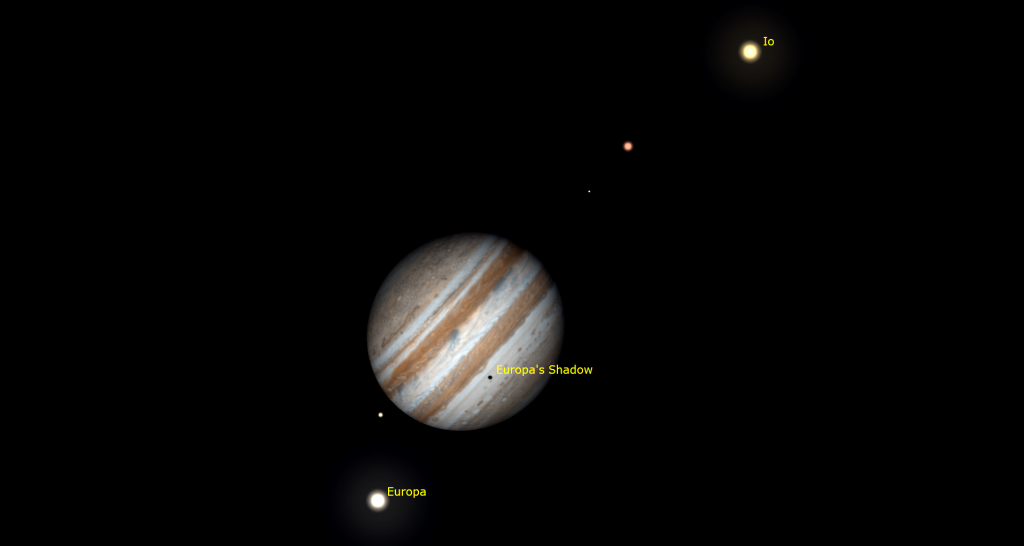

Any binoculars will show Jupiter’s four Galilean moons named Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto lined up beside the planet. Those moons complete orbits of the planet every 1.7, 3.6, 7.2, and 16.7 days, respectively. If you see fewer than four moons, then one or more of them is crossing in front of or behind Jupiter, or hiding in Jupiter’s dark shadow – or two of the moons are very close together, or one moon is eclipsing or occulting another one. Tonight (Sunday) in the Americas, all four moons will gather to one side of Jupiter.

Even a small, but decent quality telescope can show you Jupiter’s dark belts and light zones, which are aligned parallel to its equator. With a better grade of optics, Jupiter’s Great Red Spot, a cyclonic storm that has raged for hundreds of years, becomes visible for several hours when it crosses the planet every 2nd or 3rd night. For observers in the Americas, that GRS will cross Jupiter’s disk late on Monday, Thursday, and Saturday night, and before dawn on Monday, Thursday, and Saturday morning. If you have any coloured filters or nebula filters for your telescope, try enhancing the spot with them.

From time to time, observers with good quality telescopes can watch the black shadows of the Galilean moons travel across Jupiter’s disk. In the Americas, the small shadow of Europa will cross near Jupiter’s equator on Wednesday night, October 2 between 11:55 pm and 2:15 am EDT (or 03:55 to 06:15 GMT).

Last planet up, literally, will be Mars. Starting this week, the red planet will officially join the evening sky when it rises in the east by midnight – although it might be easier to view it while it’s very high in the eastern sky around 6 am local time. Mars’ reddish speck will shine about 2.2 fist diameters to Jupiter’s lower left. Mars’ relatively faster orbital motion will increase its separation from Jupiter a little more each morning. If you are under the stars during the wee hours, you’ll notice the bright winter constellations (Auriga, Taurus, Gemini, Orion) around Jupiter and Mars – your clue that those planets will be showcased after dinner this winter, when we always see those constellations.

Mars will become hidden by the morning twilight long before brilliant Jupiter does. In a telescope, the red planet will appear as a small, rusty-coloured disk. Its position on the far side of the sun from Earth, 185 million km from Earth, will keep the planet looking small until later this year. This week, Mars will only be 88%-illuminated because its angle from the sun is 83°. The planet will spend this week trekking eastward, down toward the star Wasat, which marks the waist of Pollux, the lower, eastern brother of Gemini (the Twins).

Cygnus Soars Overhead

With the moon will not brightening the evening sky this week, darkness arriving by 8:30 pm, evening temperatures being mild, and the outdoors bug-free, this will be a great week to get out under the stars – if Hurricane Helene hasn’t brought you clouds.

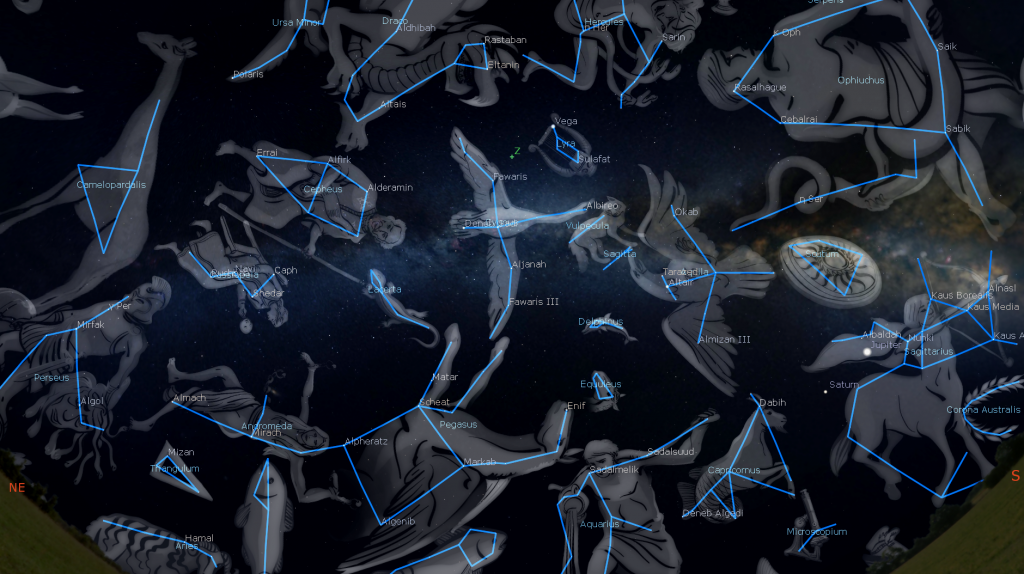

Objects in the sky directly overhead will always appear at their best because you are seeing them through the least amount of intervening air. In mid-evening during early October every year, the constellations of Lyra (the Harp), Cygnus (the Swan), and Draco (the Dragon) surround the zenith. Let’s soar into Cygnus!

Head outside on the next clear evening, face southwest, and look nearly overhead for the very bright star Vega. To its upper left is the realm of the great constellation Cygnus (the Swan). The bird’s brightest stars also form the asterism called the Northern Cross. In size, Cygnus is the 16th largest of the 88 official constellations. By using your closed fist held at arm’s length, you can see that the bright stars of the swan span more than two fists (or 22°) head to tail, and nearly four fists (or 36°) across the wingspan. Its official boundary includes a large northeastern section that is devoid of bright stars, but is loaded with rich nebulae and star fields.

Cygnus’ position 40° north of the celestial equator allows the constellation to be visible from every city on Earth. Antarctica sees no portion of it, observers at the southern tip of South America only ever glimpse its southernmost stars, and the rest of the Southern Hemisphere sees it only at this time of year – on (their) late-winter, early spring evenings. For observers in mid-northern latitudes around the world, some of Cygnus’ more northerly stars are circumpolar – that is, they never drop below the horizon.

This constellation is one of the few that truly resembles its name. In Greek mythology, Cygnus was Zeus disguised as a beautiful swan to seduce Leda, the mother of Helen of Troy. Cygnus was also said to represent mourning Orpheus, his harp in the form of nearby Lyra (the Lyre). The Arabs envisaged the stars of Cygnus as a hen. The Dakota people of North America saw a salamander, the Ojibwa people imagined a crane, and the Mongolians a bow and arrow. Ancient Chinese astronomers used a different grouping of stars and formed a bridge of magpies crossing the river of the Milky Way.

When you face south, the swan is flying down toward the right. (You might want to grab a chaise or gravity chair for this, so you can lie back and look up.) Starting at Vega, shift your gaze 2.3 fist diameters to the left (or 23° or to the celestial east) to the bright, blue-white star Deneb, which marks the tail of the swan. (The name means “tail” in Arabic.) Shining at magnitude 1.25, Deneb is the brightest of the swan’s stars, so it is also named Alpha Cygni. Can you tell that it is several times fainter than Vega’s magnitude 0.00?

Deneb is located at a whopping 2,550 light-years away from our solar system. It shines as brightly as it does because this luminous, supergiant star emits many tens of thousands of times more visible light than our Sun. The slow wobble, or precession, of the Earth’s rotation axis will cause Deneb to replace Polaris as Earth’s northern Pole Star around the year 9,800. The last time it did so was around 16,000 BCE.

Sadr is the prominent star located about a palm’s width to the lower right (or 6° to the celestial southwest) of Deneb. It marks the centre of the swan’s body (and the giant cross). The name is derived from an Arabic expression for “the hen’s breast”. Even though it’s somewhat closer to us (1,800 light-years) than Deneb, Sadr (or Gamma Cygni) shines about 2.5 times fainter than Deneb. It’s also somewhat cooler than Deneb, giving it a creamier colour.

The swan’s head is marked by a much dimmer star named Albireo. That star sits approximately 1.6 fist widths to the lower right (or 16° to the celestial southwest) of Sadr – swans have long necks! Albireo is also parked close to the centre of the Summer Triangle asterism. Albireo is a favorite telescope target at summer star parties because it divides into a coloured double star when viewed in a small telescope. The two stars show as a lovely sapphire (blue) and topaz (yellow) in colour because their photospheres are 11,000 K and 4,400 K, respectively.

Measurements from the Gaia Space Telescope indicate that Albireo is likely only a line-of-sight double – a happenstance of geometry from our perspective. The brighter yellow star sits 328 light-years away from us, and the dimmer blue star is 389 light-years away. They’re close enough to one another to be gravitationally bound together – but Gaia found that they are travelling in much different directions – uncommon in stellar siblings. Albireo was given its single name before telescopes were invented and revealed that it was actually a duo. Its alternate designation is Beta1,2 Cygni. The numerals refer to each partner.

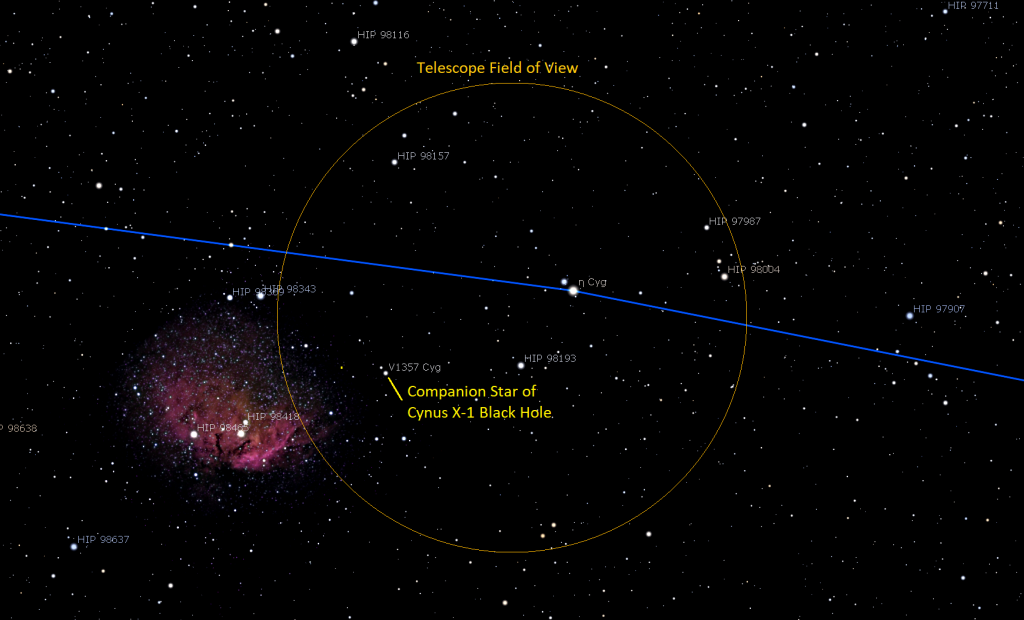

See if you can spot a medium-bright star positioned about midway along the swan’s long neck, between Sadr and Albireo. That’s Eta Cygni or (η Cyg), a warm-tinted star located about 135 light-years from Earth. This aging star has started to fuse helium in its core. Strong binoculars and backyard telescopes can reveal a magnitude 8.8, blue-white star named HD 226868 and V1357 Cygni sitting 26 arc-minutes (a full moon’s diameter) to the lower left (or celestial east) of Eta. This hot, O-class star is emitting copious amounts of X-ray radiation.

In 1971, astronomer Tom Bolton of the University of Toronto used the 74” telescope at the David Dunlap Observatory in Richmond Hill, Ontario to analyze the light from V1357. He determined that something dark and massive was tugging it around in an orbit that repeated every 5.6 days. That invisible object came to be known as Cygnus X-1, the first confirmed black hole! The Canadian rock band Rush wrote a song about it. Listen to it on YouTube here! Astro-imagers who have photographed the nearby HII emission nebula named the Tulip Nebula and Cygnus Star Cloud or Sharpless 2-101 have likely included the Cygnus X-1 system, “invisible to telescopic eyes”!

With Deneb, Sadr, Eta Cygni, and Albireo running tail to head, you should now be able to locate a long, crooked chain of slightly dimmer stars arranged from lower left to upper right – forming the swan’s broad wings. Ancient Arab astronomers dubbed those stars “the Riders” – like a camel caravan, perhaps? Each wing extends about two fist diameters from Sadr and contains three stars. Let’s tour the wings.

Moving less than a fist’s width to the upper right (or 8° to the celestial northwest) from Sadr, we first arrive at Fawaris or Al Fawaris (“the Riders”) also known as Delta Cygni or (δ Cyg). The star has also been called Rukh, after the giant Roc in Middle Eastern mythology (and some sword and sandal movies). Decent telescopes at high magnifications should be able to split that star into a pair of greenish-blue and yellow-white stars. Al Fawaris will also take a turn as Earth’s pole star.

A further jump of 7° to the upper right lands us at white Iota Cygni or (i Cyg). A couple of finger widths beyond Iota sits yellowish Kappa Cygni or (κ Cyg), the wingtip star. Kappa is an aging G-type star (like our sun) – buts it has swelled to almost ten times the size of the sun. Both Iota and Kappa sit about 120 light-years away from us. Kappa is sometimes labelled on sky charts as Fawaris I.

Let’s trace out the lower wing. Moving about 8° downwards to the left from Sadr we find the bright, yellow-orange star Aljanah or Gienah, both names originating from the Arabic expression for “Wing of the Swan”. Also known as Epsilon Cygni or (ε Cyg), 72 light-years distant Gienah is an old star that is beginning its death process.

A palm’s width to the lower left of Gienah you should spot a medium-bright, yellow-orange star named Zeta Cygni or ζ Cyg or Fawaris III. A little more bending to the left and another palm’s width jump arrives at the tightly separated double star Mu1,2 Cygni (μ1,2 Cyg). This pair of stars is orbiting one another with a period of about 790 years. Because their orbit is nearly edge on to us, they slowly move closer together and draw farther apart over the decades. Right now they are separating.

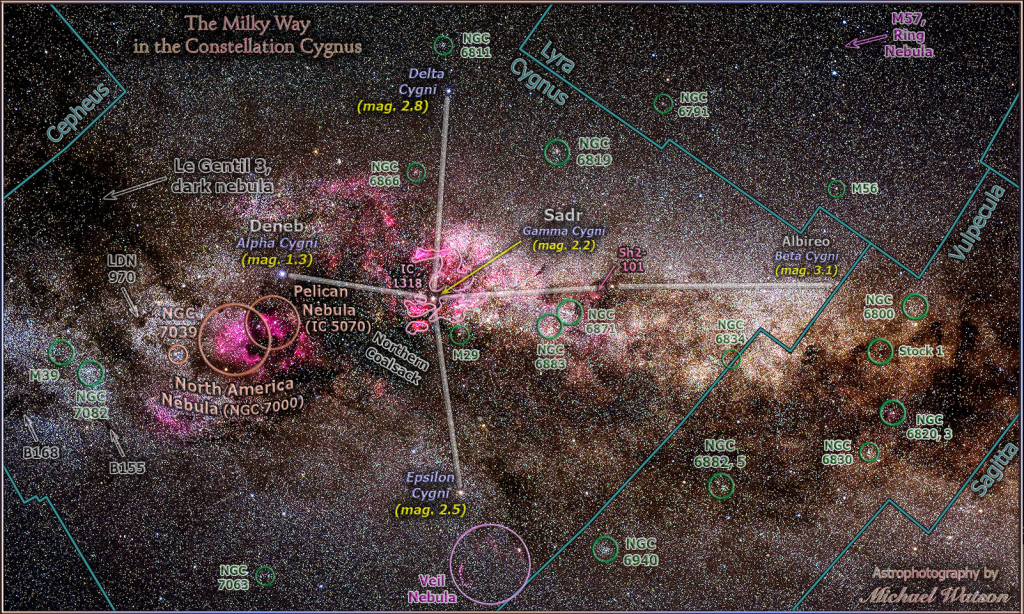

If you can leave the light polluted skies of the city, notice how the Milky Way divides into two strips where it passes through Cygnus. The dark median between those zones is opaque interstellar dust concentrated within the plane of our galaxy. Grab your binoculars and look for some of Cygnus’ wonderful nebulae – clouds of mainly hydrogen gas and dust that glow in pinks and blues – lit from within by the radiation emitted by the stars they contain. These large objects are best seen with binoculars, and sometimes your unaided eyes, under very dark, moonless skies. Check them out!

A few finger widths to the lower left of Deneb is the North American Nebula (also NGC 7000), so-named for its distinctive shape. It’s quite easy to see as a faint, bright patch in binoculars. It’s more than three times larger than a full moon. The Pelican Nebula, a smaller patch to its right, is part of the same gas cloud – but separated from the other piece by dark foreground dust.

A faintly glowing region called the Gamma Cygni Nebula surrounds Sadr. This nebula, which is nearly 5,000 light-years away from us, spans six full moon diameters across! Sadr is not related to the nebula, though – the star is only half as far away as the nebula. Before moving on, look for an extra-dark patch of sky sitting two finger widths to the upper left of Sadr. The patch, almost a fist diameter across and several finger widths tall is more dark interstellar dust that is blocking the light from the Milky Way’s stars beyond it. The patch is also known as the Northern Coalsack. (The larger, darker, geniune Coalsack Nebula is located beside Crux, the Southern Cross. But it’s only visible from the Southern Hemisphere.)

The large, delicate, and pink Veil Nebula or Cygnus Loop sits about three finger widths below Aljanah / Gienah. Its roughly circular shape, five full moon diameters across, is the tattered remnant shell of a supernova that occurred five to eight thousand years ago. A particularly strong section of the nebula sweeps across a foreground star named 52 Cygni. That star sits a few finger widths below Aljanah / Gienah. Put your lowest magnification eyepiece in your telescope, point it at 52 Cygni, and then look for a narrow slash of dim light crossing the field of view through the star. Then you can carefully follow the giant loop across the stars – especially if you have a nebula filter in your telescope.

Telescope owners should look for the Blinking Planetary. It’s a stellar corpse (like Lyra’s Ring Nebula) that plays an optical illusion on you. When you look straight at it, its central white dwarf shines as a tiny pinprick. But use averted vision, and a blue halo pops into view. You can make the halo appear and disappear by shifting your gaze. It’s fun! Find the object by doubling a line drawn from Kappa through Iota.

If you are observing from a dark location, you should see that the band of the Milky Way runs directly through Cygnus – as if she is about to land on that river! The rich star fields surrounding the constellation are terrific for laying back and scanning with binoculars. You might find one of the many open star clusters in Cygnus, such as the Cooling Tower Cluster (or Messier 29), which is located less than two finger widths below Sadr, two more bright clusters along the neck to the left of Eta Cygni, the bright cluster Messier 39 located a fist’s diameter to the upper left of Deneb, and several clusters surrounding Delta Cygni.

Let me know how your exploration of Cygnus goes.

Diving into Delphinus

If you missed last week’s tour of the cute little constellation named Delphinus (the Dolphin), I posted it here.

Public Astronomy-Themed Events

Every Monday evening, York University’s Allan I. Carswell Observatory runs an online star party – broadcasting views from four telescopes/cameras, answering viewer questions, and taking requests! Details are here. They host in-person viewing on the first clear Wednesday night each month. Other Wednesdays they stream views online via the observatory YouTube channel. Details are here.

On Wednesday evening, October 2 at 7:30 pm EDT, the RASC Toronto Centre will host their free, public Recreational Astronomy Night Meeting, live streamed at https://www.youtube.com/rasctoronto/live. Talks will include The Sky This Month, powering a telescope, and Mercury’s salt glaciers. Details are here.

Keep your eyes on the skies! I love getting questions and requests. Send me some!