Earlier Evenings Remain Moonless, Gazing at Giant Galaxies, and All the Planets Available!

The Cygnus Loop, also known as the Eastern and Western Veil Nebulae, are a gigantic remnant of a supernova in the southern wing of the Swan that spans more than five full moon diameters. It is visible in binoculars under very dark skies every summer. The bright star at right named 52 Cygni that the western veil passes through is easily seen by unaided eyes. This image by Joachin Ferreiros was the NASA APOD for Nov 26, 2012.

Welcome to September, Stargazers!

Here are your Astronomy Skylights for the week of September 1st, 2024 by Chris Vaughan. Feel free to pass this along to your friends and send me your comments, questions, and suggested topics. You can also follow me on Twitter as @astrogeoguy! Unless otherwise noted, all times are expressed in Eastern Time. To subscribe to these emails please click this MailChimp link.

If you’d like me to bring my Digital Starlab portable inflatable planetarium to your school or other daytime or evening event in Simcoe, Grey, and Bruce Counties, or deliver a virtual session anywhere, contact me through AstroGeo.ca, and we’ll tour the Universe, or the Earth’s interior, together! My book with John A. Read entitled 110 Things to See With a Telescope is a guide to viewing the deep sky objects in the Messier List – for both beginners and seasoned astronomers. DM me to order a signed copy!

I discuss both definitions of autumn and the shortening amount of daytime as we start September. The moon will return to the west after sunset, but it won’t prevent us from enjoying the summer Milky Way and its treats, giant galaxies in the eastern sky, and Comet 13P/Olbers in the western sky. All of the planets will be available to view – but only if you are willing to be out before sunrise. Saturn will host a double shadow transit. Read on for your Skylights!

The State of Daylight and Stars

Welcome to September – and meteorological autumn! We’re used to hearing about the first day of a new season on the news or social media (or from me) – but there’s another valid point of view on the turning of the seasons.

The astronomical definition of the seasons uses the sun’s position along the ecliptic and therefore the Earth’s axial tilt towards and away from the sun to define the four parts of the year. On the winter solstice (in December for Northern Hemisphere residents), the north pole of the Earth is tilted by 23.5° away from the sun, producing shorter days, a low noonday sun, and less warming. At the summer solstice, which arrives six months later, the pole is tilted by the same amount towards the sun, delivering a high noon sun that delivers maximal amounts of daylight and plenty of solar heating. The autumn and spring equinoxes occur “halfway” between the solstices.

Each of those four events occurs about three weeks into December, March, June, and September. But those of us living at middle latitudes are already seeing signs that the seasons are turning – leaves dropping from the trees, chillier nights, plants gone to seed, etc. For that reason, non-astronomers have adopted meteorological seasons that commence on the first day of each of those months. I can’t find much fault in that.

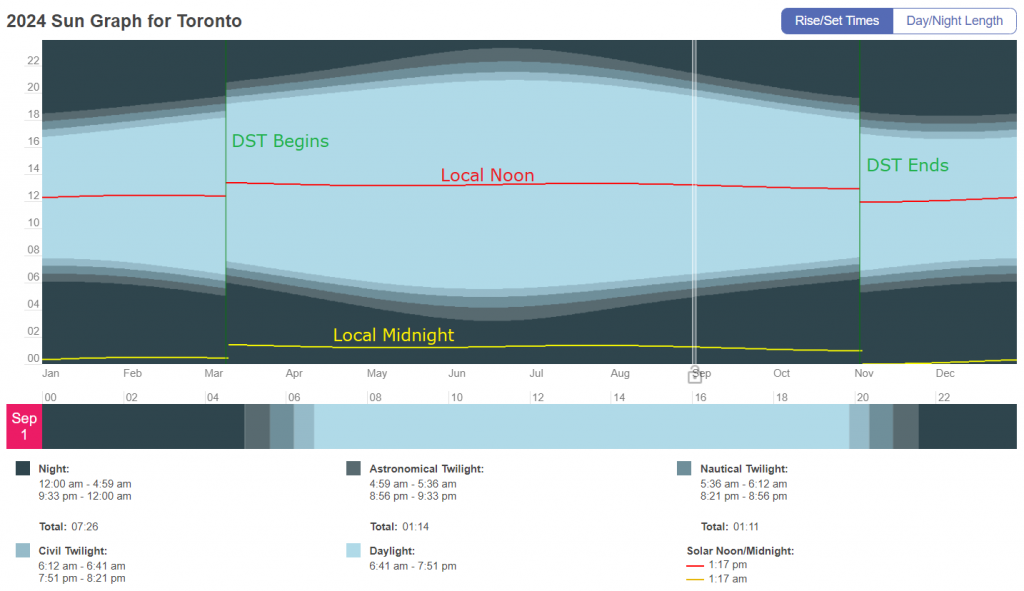

The balance between daylight and darkness varies through the year due to that axial tilt change. A yearly graph of the amount of minutes of daylight we receive each day at any particular latitude looks sinusoidal – and it gets more curvy the farther you are from the equator. The top of the curve (most daylight) falls on the summer solstice. The bottom of the curve (least daylight) is on the winter solstice. The graphs are close to horizontal for a few weeks around the solstices, so the amount of daylight on either side of those two events barely changes. That’s when winter really feels like it has come to stay.

The fun happens around the equinoxes where the graph is steepest. The rate that we gain or lose daylight is at a maximum – though it really picks up steam for a month ahead of each equinox and a month beyond it. For folks living at latitudes like Toronto, we are receiving 2.9 minutes less daylight with each passing day now – or 20 minutes less per week! The daylight reduction will max out at 2:97 minutes per day by September 22’s equinox. You can get your own graph at www.timeanddate.com/sun.

This week at 43° North latitude, sunset will occur around 7:45 pm Daylight Time. The sky will get dark enough to see the first “wishing stars” by 8:15 pm (the end of Civil Twilight), the medium-bright stars by around 8:50 pm (the end of Nautical Twilight), and the fully dark sky around 9:30 pm (the end of Astronomical Twilight). Remember – those times are advancing by 20 minutes per week! For early risers the sky will begin to brighten after 5 am local time.

Stargazers welcome autumn. During May-June-July we had to wait until 11 pm to see any stars! Now we can view them starting in mid-evening. It’s also a terrific time of the year for public star parties. We can see the summer stars after dark, the autumn stars in late evening, and the winter constellations after midnight. Youngsters can join in the fun, even on school nights. I’ll be setting up my scopes in public places around town soon. A Google search should turn up folks like me in your own town.

Put on a sweater, get outside, and look up! The summer bugs are gone and the winter snow hasn’t flown. Don’t put it off too long, though. Once we approach October in the Great Lakes region, we get a lot more cloudy nights.

Zodiacal Light Alert

During autumn at mid-northern latitudes every year, the ecliptic extends nearly vertically upward from the eastern horizon before dawn. That geometry favors the appearance of the faint zodiacal light in the eastern sky for about half an hour before dawn on moonless mornings. Zodiacal light is sunlight scattered by interplanetary particles that are concentrated in the plane of the solar system – the same material that produces meteor showers. It is more readily seen in areas free of urban light pollution.

Between now until the full moon on September 17, look for a broad wedge of faint light extending upwards from the eastern horizon and centered on the ecliptic. It will be strongest in the lower third of the sky below the twin stars of Gemini. Don’t confuse the zodiacal light with the Milky Way, which is positioned nearby in the southeastern sky.

The Moon

After spending a week in the predawn sky approaching the sun, the moon will return to evening this week all around the world – but the shallow angle that its orbit is making with the western horizon after sunset will keep the moon down among the trees, even though it will be setting later and waxing in phase every evening. That will give end of summer stargazers another week to peruse dark delights in the Milky Way!

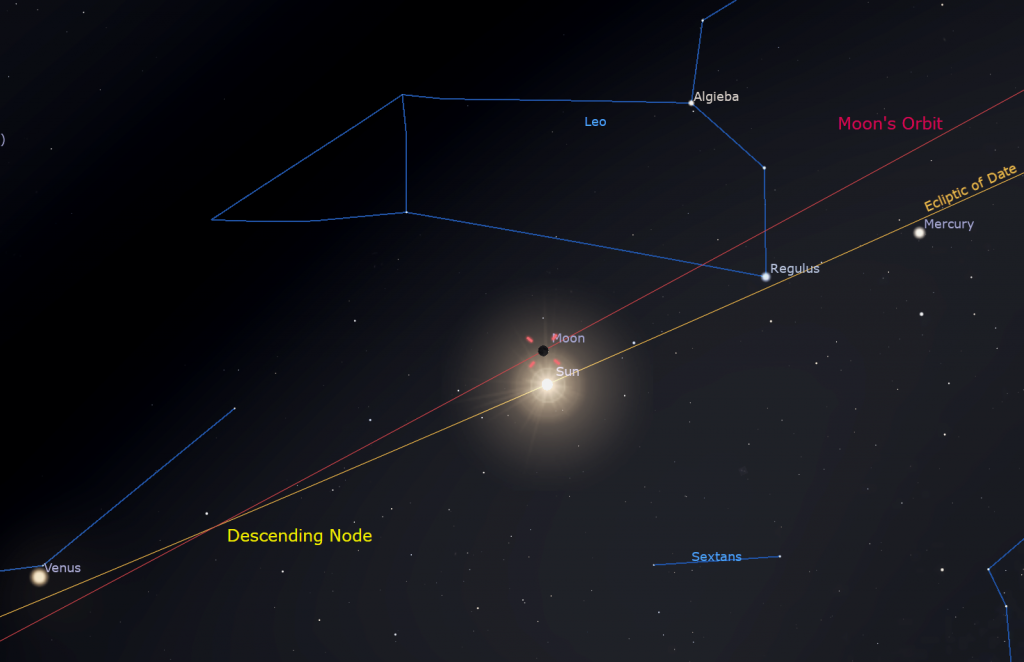

You may have glimpsed the very slender crescent moon posing with Mercury over the eastern horizon before sunrise this morning (Sunday). That was our final chance to see it before it passes the sun at new moon. That phase will arrive on Monday at 9:56 pm EDT or 6:56 pm PDT, which converts to 01:56 Greenwich Mean Time on Tuesday elsewhere on Earth. While new, our natural satellite will be located in Leo (the Lion), 1.5 degrees north of the sun.

The period that the phases of the moon repeat on is about two days longer than the time it takes to orbit the Earth, 27.32 days. That means that each new moon event occurs at a different place along the moon’s orbit – about 30° farther east each month. The moon’s orbit is tilted by 5.14° compared to the ecliptic, which is the sun’s path around the sky. Those two imaginary circles intersect at two places in the sky, like a pair of hula hoops. The intersection points are called nodes. When you hear about the moon or a planet being at its ascending node, it is sliding through its orbit-and-ecliptic intersection point “upwards”, into the northern sky side of the ecliptic. The moon’s descending node is in Virgo (the Maiden), which is next door to Leo. At the next new moon on October 2, the moon will pass much closer to the sun while they are both in Virgo, producing an annular solar eclipse that will only be visible way down at the southern end of South America. Much of South America will see a partial solar eclipse, but northerners will not.

For those of us at mid-northern latitudes, the young crescent moon will sit just to the upper left of the sun when it sets on Tuesday. But the time to try to spot it will be Wednesday, when the moon will be less than a binoculars’ field of view to brilliant Venus’ lower right for a short time after sunset. (Don’t train binoculars or a telescope on them until after the sun has completely set.)

On Thursday, the moon’s crescent will be a bit thicker, and the moon will be farther from the sun – making it easier to see. After 24 hours of orbital motion, the moon will be posing a palm’s width (still binoculars-close) to the left of Venus. To see either of those objects you’ll need an unobstructed, cloud-free view to the west. The story will continue through the week, with the moon hopping farther and farther to the left (celestial east) of Venus – but staying very low in the sky.

Your first easy view of the moon in a darkening sky will likely be on Saturday, when its 20%-illuminated crescent will still be above the horizon while the stars are starting to shine. The moon will end the week shining in Libra (the Scales) until mid-evening – still low, though!

The Planets

For the first half of September, you can see all the planets – though you’ll need to get up before sunrise for two of them.

Starting in evening, Venus remains stubbornly pinned above the western horizon after sunset for those of us viewing it from mid-northern latitudes, even though it is continuing to increase its angle from the sun every day. If your western horizon is unobstructed and free of cloud or haze, you can start to look for Venus’ very bright dot starting around 8 pm local time. The planet will be the bright, star-like object gleaming less than a fist’s width above the horizon. If the bright speck you see is moving left or right, it’s an aircraft. Wait until the sun has fully set before using binoculars. Folks living closer to the tropics are already easily seeing Venus gleaming between the palm trees after sunset. As we move past the September equinox, she will start to climb higher and become our brilliant “Evening Star” gleaming high in the western sky throughout fall and winter. Don’t forget that the young crescent moon will shine to Venus’ left (or celestial east) during this week.

Saturn will be the showpiece for evening planet-viewing this week. On Saturday, Saturn will reach opposition for 2024. Planets at opposition rise at sunset and set at sunrise because Earth is positioned between them and the sun. That also minimizes our distance from them. This weekend, Saturn will be at a distance of 1.295 billion km, or 72 light-minutes from Earth. It will shine at magnitude of 0.57 – its brightest for the year. In a telescope Saturn’s globe and rings will show maximum apparent diameters of 19 arc-seconds and 44 arc-seconds, respectively. Opposition is also the optimal time to view Saturn’s moons through a backyard telescope in a dark sky.

The ringed planet will clear the eastern rooftops by about 9 pm – but you’ll get the clearest views of Saturn in a telescope between 10 pm and 4 am, when it’s highest in the sky. (Thankfully, those times are advancing by half an hour each week.) The faint stars of Aquarius (the Water-Bearer) will be shining just to the right Saturn. Binoculars will show you a bent-line trio of stars named Psi Aquarii sparkling to Saturn’s lower right. The lower two are white, while the higher one is golden. Two redder stars named Phi and Chi Aquarii will appear to Saturn’s upper and lower right, respectively.

The bright trio of the Summer Triangle asterism stars will sparkle well above, and the Great Square of Pegasus stars will be off to the planet’s upper left. The very bright star Fomalhaut (or Alpha Piscis Austrini, the Southern Fish) will shine two fist diameters below Saturn all year. Despite its peak brightness, the white star Vega will outshine the yellowish planet.

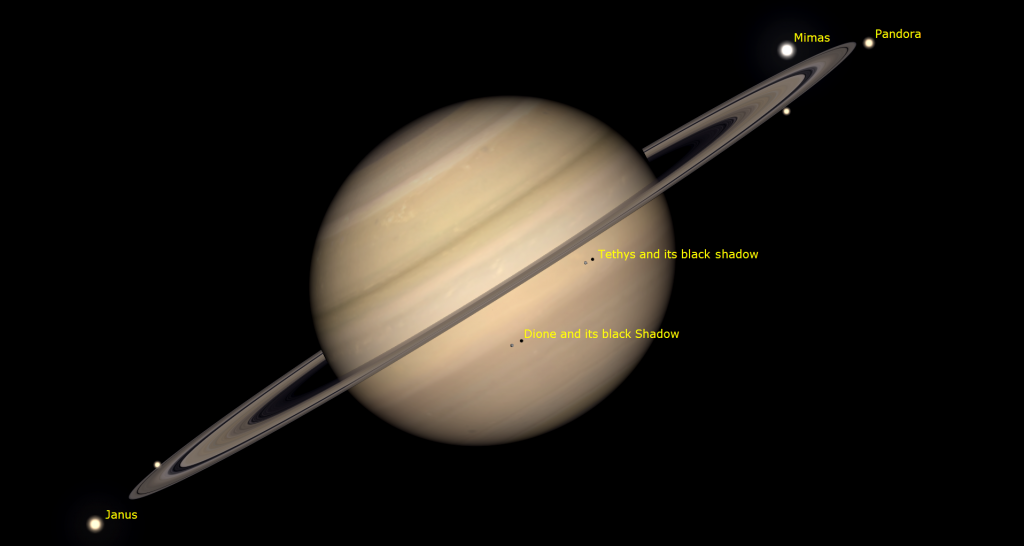

Saturn’s rings, which will effectively disappear when they become edge-on to Earth next March, already appear as a thick line drawn through the planet’s globe. Good binoculars can hint that Saturn has rings, and any size of telescope will show them and Saturn’s moons! Usually, Saturn’s moons are arrayed all around the planet – unlike Jupiter’s Galileans moons, which are always in a line. But Earth’s perspective of the Saturn system this year and next year will line up its moons with the rings.

Saturn’s largest and brightest moon Titan never wanders more than five times the width of Saturn’s rings from the planet. The much fainter moon named Iapetus “eye-YA-pet-us” can stray up to twelve times the ring width during its 80-day orbit of Saturn. The next brightest moons Rhea “REE-ya”, Dione “Dee-OWN-ee”, Tethys “Teth-EES”, Enceladus “En-SELL-a-dus”, and Mimas “MY-mass” all stay within one ring-width of Saturn.

Titan will move from just below Saturn (or celestial south of it) tonight, stretch far to Saturn’s upper right (celestial west) on Thursday-Friday, and then slide back toward Saturn. (Remember that your telescope will probably flip the view around.) The rest of the moons will be tiny specks in a line beyond the rings. You may be surprised at how many you can see through your telescope if you look closely.

Earth’s perspective of the Saturn system will also cause Saturn’s moons and their small black shadows to frequently cross its disk – but you’ll need a very high quality telescope to watch those. Tethys and its shadow will cross Saturn near the rings on Monday night from 9:25 pm to 12:15 am EDT, and Dione plus its shadow will join them after 10:10 pm EDT – a rare two transits at a time! Rhea and its shadow will cross Saturn’s mid-southern latitudes on next Sunday morning from 1:45 to 4:40 am EDT.

Neptune will rise 20 minutes after Saturn and follow it across the sky every night. The distant, blue planet will be spending this year in western Pisces (the Fishes), a generous fist’s width to the lower left (or 12° to the celestial ENE) of Saturn. Neptune doesn’t move very quickly through the stars. Neptune will also be located a palm’s width below the circle of stars that forms Pisces’ western fish, and about two finger widths above (or 2° celestial north) of the upright rectangle formed by the medium-bright stars 27, 29, 30, and 33 Piscium. For now, the best time to look at Neptune is while it’s higher up and the sky is dark – between about 10:30 pm and 5:30 am local time.

After today, Jupiter will rise before midnight every night – kicking off a nine-month residence in the evening sky. Generally speaking, anyone outside between about 1:15 am and sunrise will easily spot the giant planet blazing away as it climbs the eastern sky. The reddish dot of 16 times fainter Mars will be visible to the lower left of Jupiter. Mars’ relatively faster orbital motion will increase its separation from Jupiter each morning. Both planets are shining in Taurus (the Bull), between the critter’s horns about a fist’s width to the left (or 10° to the celestial ENE) of his brightest star, reddish Aldebaran.

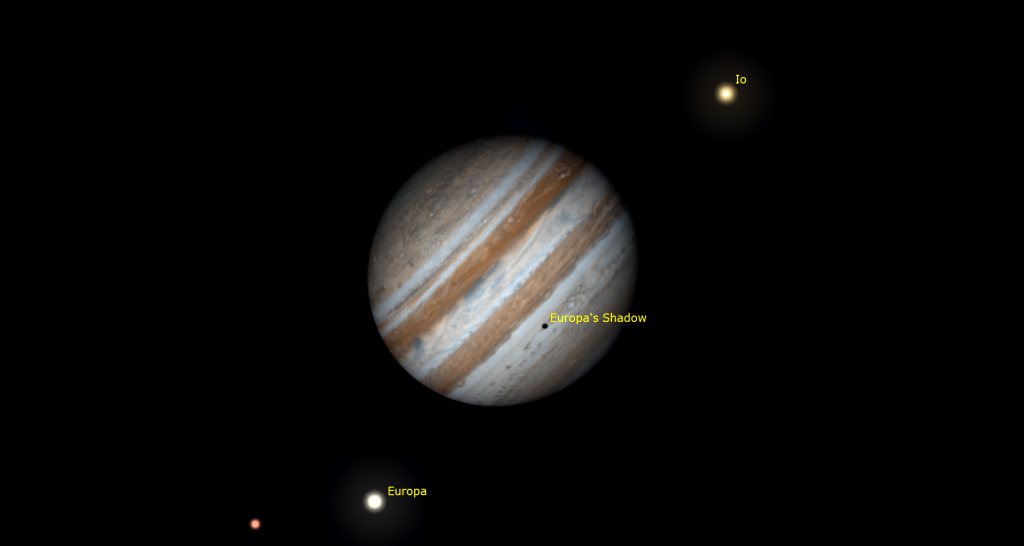

Any binoculars will show Jupiter’s four Galilean moons named Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto lined up beside the planet. Those moons complete orbits of the planet every 1.7, 3.6, 7.2, and 16.7 days, respectively. If you see fewer than four moons, then one or more of them is crossing in front of or behind Jupiter, or hiding in Jupiter’s dark shadow – or two of the moons are very close together, or one moon is eclipsing or occulting another one.

Even a small, but decent quality telescope can show you Jupiter’s dark belts and light zones, which are aligned parallel to its equator. With a better grade of optics, Jupiter’s Great Red Spot, a cyclonic storm that has raged for hundreds of years, becomes visible for several hours when it crosses the planet every 2nd or 3rd night. For observers in the Americas, that GRS will cross Jupiter’s disk in the wee hours of Monday, Thursday, and Saturday, and before dawn on Wednesday and Friday morning. If you have any coloured filters or nebula filters for your telescope, try enhancing the spot with them.

From time to time, observers with good quality telescopes can watch the black shadows of the Galilean moons travel across Jupiter’s disk. On Sunday morning, September 8, the black shadow of Europa will travel across Jupiter from 2:43 to 5:10 am EDT (or 06:43 to 09:10 GMT).

Mars will rise about 45 minutes after Jupiter, and fade from sight in the morning before Jupiter does. In a telescope, the red planet will appear as a small, ruddy-coloured disk. Its position on the far side of the sun from Earth is keeping the planet looking small until later this year. If you do check it out, take notice that Mars is only 88%-illuminated because its angle from the sun is 74°. Mars is currently travelling in front of the faint winter Milky Way and posing next to some star clusters. On Sunday night, September 8, Mars will pass less than a finger’s width to the lower right (or 0.9 degrees to the celestial south) of the large open star cluster in Gemini named the Shoe-Buckle Cluster, Messier 35, and NGC 2168. The planet and the distant cluster will share the field of view in a backyard telescope from Friday to Wednesday, and in binoculars from now to September 18. Mars will approach the cluster from the right (celestial west) this week, but your telescope will likely flip and/or mirror the view.

Uranus can be observed between midnight local time and dawn. The planet will rise around 10:40 pm this week and climb to high in the couth by morning. In binoculars and a backyard telescope Uranus will appear as a dull, non-twinkling, blue-green star positioned about a palm’s width to the lower right of the bright Pleiades star cluster. The slow-moving, distant planet will remain near that bejeweled patch until 2027! Uranus will begin its westward retrograde loop today. It will creep west against the stars, peak in size and brightness on opposition night November 17, and then return to its usual easterly motion at the end of January.

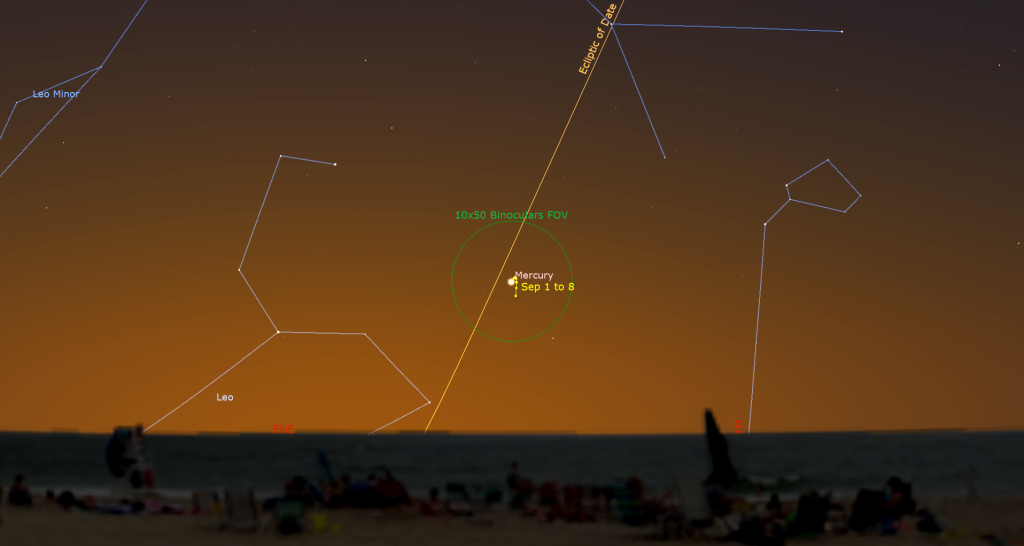

To round out our planetary perusal, Mercury will shine above the eastern horizon before sunrise this week and next. The planet has been swinging away from the morning sun in its best morning apparition of the year for Northern Hemisphere observers (but a very poor one for those at southern latitudes). The speedy planet will stretch to a maximum of 18° west the sun on Thursday, September 5 – with peak visibility arriving around 6 am local time for several mornings. You’ll need an unobstructed eastern view that is free of clouds and haze. Mercury will be a bright, unmoving dot a short distance above the horizon. (Any white specks that are shifting left or right will be aircraft.) It is safe to use binoculars for your search, but turn them away before the sun rises. In a telescope, Mercury will show a half-moon shape, though the planet may be blurry or “swimming” due to the extra-thick blanket of atmosphere you will be viewing it through.

Comet Olbers

While the moon setting early this week, conditions are still favourable for seeing Comet 13P/Olbers after dusk using large binoculars and backyard telescopes. Comets appear as faint, greyish fuzzballs – sometimes with a slight greenish tint – and sometimes with a tail. I’ll post an image of it that I got last night in my Seestar S50 robotic telescope, despite some bright streetlights here in Collingwood.

This comet has already passed its peak brightness, but it is currently conveniently positioned in the lower part of the western early-evening sky for mid-northern latitude observers. Recent brightness estimates have been in the magnitude 8.4 range.

This week comet 13P/Olbers will be travelling right-to-left (or celestial southeast) from the faint constellation of Coma Berenices (Berenice’s Hair) and into more prominent stars of Boötes (the Hunter), home of the very bright star Arcturus. Tonight (Sunday) it will appear several finger widths above the medium-bright star Diadem. By next Sunday it will have shifted to a similar distance below the brighter star Upsilon Boötis. Start your hunt for the comet as soon as the sky gets dark because it will drop too low for decent views by 10 pm local time. Note that your telescope will likely flip and/or mirror the view in my chart.

Galaxy Gazing on Moonless Nights

‘Tis the season to look for the farthest object a human eyeball can see without help* – the Andromeda Galaxy, or Messier 31. This large spiral galaxy is a big sister to our own Milky Way galaxy. It is 2.5 million light-years away from our sun, meaning that its stars’ light has been journeying to us for that length of time. That means that if there are alien astronomers living there and looking back at us, they are seeing our solar system as we appeared 2.5 million years ago!

In early September, the Andromeda Galaxy sits about one-third of the way up the east-northeastern sky at 9 pm local time. (It will be higher later on.) To locate it, you can first find the medium-bright star Mirach. It’s the second star when hopping left (celestial east) from Alpheratz, which marks the eastern corner star of the Great Square of Pegasus. Then look for a dimmer star shining a few finger widths above (or 4° NE of) Mirach. The Andromeda Galaxy is higher again by that same distance. Alternatively, you can use the highest three stars of the distinctive, W-shaped constellation Cassiopeia (the Queen). They form an arrow that points directly at M31.

Under dark skies, using your unaided eyes only, you should be able to see a faint fuzzy patch that is elongated left to right. Try directing your attention a little ways away from the galaxy and it will brighten – the averted vision trick! The galaxy spans six full moon diameters across the sky, but only its bright core and the surrounding, inner halo are usually seen visually. The galaxy is quite easy to see with binoculars. The giant galaxy is a cool object to see! Let me know if you view it.

Because telescopes have fields of view that are too narrow to see the entire galaxy, they’ll generally only show you Andromeda’s bright core. While looking, see if you can make out M31’s two small, fuzzy-looking companions, the small elliptical galaxies designated M32 and M110. M32 is closer to the main galaxy’s core and it situated just to the lower right (or to the celestial south). M110 is above (or northeast of) the main core and is slightly farther away. At 2.49 million light-years, M32 is closer to us than the Andromeda Galaxy; while M110 is 200,000 light-years farther away. (Most telescopes will flip and/or mirror image those directions.)

*Another large galaxy, called Messier 33 in Triangulum (the Triangle), is 2.75 million light-years away. Observers with very keen eyes under very dark sky conditions can sometimes see it, too – setting the record. This galaxy is tougher because it is oriented nearly face-on to Earth – so its light is spread across a large patch of sky (equal to 1.5 full moon diameters), making it dimmer overall. It sits only 1.3 fist diameters below M31, a palm’s width below the star Mirach. Wait until late evening to look for M33.

Public Astronomy-Themed Events

Every Monday evening, York University’s Allan I. Carswell Observatory runs an online star party – broadcasting views from four telescopes/cameras, answering viewer questions, and taking requests! Details are here. They host in-person viewing on the first clear Wednesday night each month. Other Wednesdays they stream views online via the observatory YouTube channel. Details are here.

On Wednesday evening, September 4 at 7:30 pm EDT, the RASC Toronto Centre will host their free, public Recreational Astronomy Night Meeting, live streamed at https://www.youtube.com/rasctoronto/live. Talks will include The Sky This Month, powering a telescope, and How Could a “Planet Killer” Help Save the Earth? A cosmic perspective. Details are here.

Eastern GTA sky watchers are invited to join the RASC Toronto Centre and Durham Skies for solar observing and stargazing at the edge of Lake Ontario in Millennium Square in Pickering on Friday evening, September 6, starting at 6 pm. Details are here. Before heading out, check the RASCTC home page for a Go/No-Go call – in case it’s too cloudy to observe.

On Friday, September 6 from 10 pm to midnight, RASC Toronto Centre will host Spectacular Saturn – The Ringed Planet at Opposition at the David Dunlap Observatory for visitors aged 7 and up. You will learn about Saturn, visit the giant 74” telescope, and view Saturn and other celestial sights through telescopes if the sky is clear. This program runs rain or shine. Details are here, and the link for tickets is at ActiveRH.

Keep your eyes on the skies! I love getting questions and requests. Send me some!