Falling Back, the Beaver Moon Entirely Eclipsed, Evening Mars Makes its Move, Max Uranus, and Taurus Shoots Stars!

This terrific image of a total lunar eclipse was captured and processed by Michael Watson of Toronto on October 8, 2014. The circumstances were similar to the total lunar eclipse that North americans will witness during the morning hours of Tuesday, November 8, 2022. As with this previous eclipse, the northern hemisphere of the moon won’t dip as deeply into Earth’s shadow on Tuesday, lightening it. More of Michael’s images can be enjoyed on his Flickr page at https://www.flickr.com/photos/97587627@N06/albums/with/72157644114323234.

Hello, Dark Evening Stargazers!

Here are your Astronomy Skylights for the week of November 6th, 2022 by Chris Vaughan. Feel free to pass this along to your friends and send me your comments, questions, and suggested topics. You can also follow me on Twitter as @astrogeoguy! Unless otherwise noted, all times are expressed in Eastern Time. To subscribe to these emails please click this MailChimp link.

If you’d like me to bring my Digital Starlab portable inflatable planetarium to your school or other daytime or evening event, or deliver a session online, contact me through AstroGeo.ca, and we’ll tour the Universe, or the Earth’s interior, together! My terrific book with John A. Read entitled 110 Things to See With a Telescope is a guide to viewing the deep sky objects in the Messier List – for both beginners and seasoned astronomers. DM me to order a signed copy!

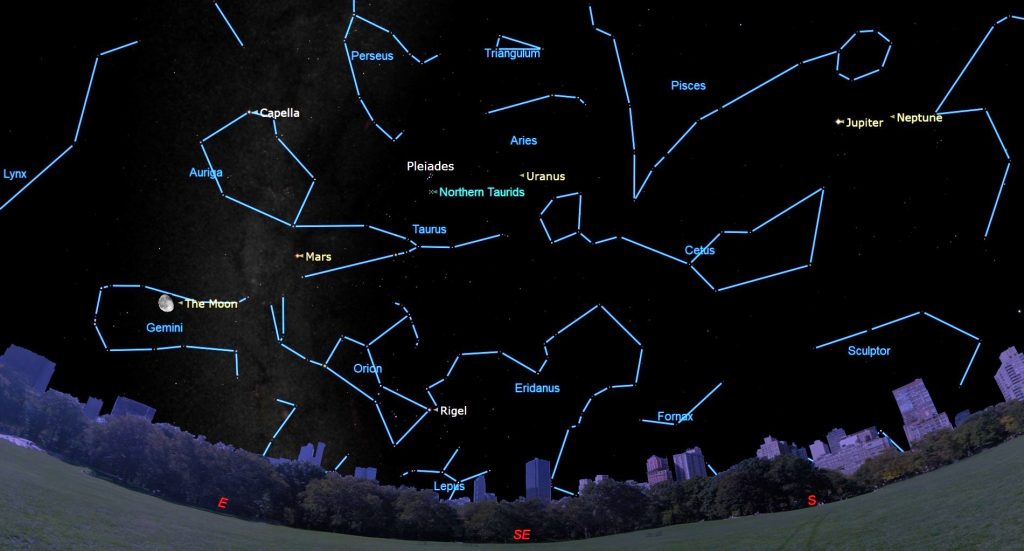

Now that North America has fallen back, the skies are darker earlier. But this week the moon will be full and bright worldwide, except on Tuesday morning when a total lunar eclipse will occur for North America! The moon will also interfere with the Northern Taurids meteor shower. Three bright planets Saturn, Jupiter, and especially Mars will parade during evening – and Uranus will reach peak visibility for the year at midweek. Read on for your Skylights!

Falling Back

Did you remember to set your clocks back by an hour? For jurisdictions that employ Daylight Saving Time (or DST, for short), clocks should have been set back by one hour at 2 am local time on Sunday morning, November 6 – or before you went to sleep on Saturday night. In North America the “Fall Back” will remain in effect until Daylight Saving Time reverts to Standard Time when we “Spring Forward” on Sunday, March 13, 2023. The changes occur on the second Sunday morning in March and the first one in November. In the Southern Hemisphere, where the seasons are flipped, the clock changes are in the opposite sense.

With the end of Daylight Saving Time we’re back to our regularly scheduled program of sunrises and sunsets. Your time zone abbreviation has changed, too. For example, 8 pm Eastern Daylight Time (EDT) is now 7 pm Eastern Standard Time (EST). For those who deal with the timing of astronomical events, the difference between your local time and the international standard of Greenwich Mean Time (or GMT), and the astronomers’ Universal Time (UT), is increased by one hour when DST ends.

For those of us in Toronto, the sun is now rising at about 7 am EST and setting at 5 pm EST. The amount of daylight is decreasing by a whopping 2.5 minutes every day – or 18 minutes every week! The end of astronomical twilight, when the sun is far enough below the horizon for the sky to reach maximum darkness, ends at about 6:39 pm. As a stargazer, I do appreciate being able to pull out the telescope earlier – but I’m not a fan of the colder temperatures and the cloudier skies of November.

By the way, if you plan to use your telescope on chilly nights, place it in a secure spot outside, with the lens cap on, at least an hour before you head out. That will give the air inside it a chance to equalize with the outside temperature – yielding sharper views. Before you bring the telescope back in, put the lens caps back on to keep the optics from frosting up – or zip it into its case, if you have one. (Or snug a garbage bag around it while it warms to room temperature.)

For most of human history people woke with the sun and went to bed at dusk. At equatorial latitudes, where most people lived, hunted, and farmed, the number of hours of daylight through the year didn’t vary too much – so that approach worked well. But, as communities spread around the world and began to use standardize working hours – especially at latitudes farther from the equator where the days lengthened and shortened dramatically throughout the year – people were forced to use artificial light indoors when the sun wasn’t shining into windows.

Scientist/naturalist Benjamin Franklin, in a satire he published while living in Paris in 1784, proposed that Parisians get out of bed earlier to take advantage of the early sunrises in summer – and thereby save money on candles and oil in evening. For the same reason, during the 19th Century it became common for schools and businesses to adjust their operating hours with the seasons – but that practice wasn’t standardized.

New Zealand entomologist George Hudson first proposed what became Daylight Saving Time in 1895 – but he wanted the clocks to shift by 2 hours! The idea then spread to England where prominent English builder and outdoorsman William Willett, who was also an avid golfer, noted that more work (and golf) could be fit into the day if the clocks were advanced during the warm months. While the British parliament toyed with the proposal for years, it was Canada that led the way on Daylight Saving Time!

The first city in the world to enact DST, on July 1, 1908, was Port Arthur, Ontario, Canada – followed soon after by Orillia, Ontario. The German Empire and Austria-Hungary adopted DST on April 30, 1916 as a way to conserve coal during World War I. Britain and most of its allies, plus many European neutrals soon followed. The USA adopted DST in 1918. Except for Canada, the UK, France, Ireland, and the United States, DST was abandoned after the war; but it was re-instated during World War II and then widely adopted as a result of the energy crisis of the 1970’s.

The Yukon, most of Saskatchewan, and parts of British Columbia don’t change their clocks, nor do India, China, Russia and swaths of Africa and Australia. The inconvenience of twice-yearly clock changes has led to calls to abandon the practice. Some jurisdictions, including Ontario, Canada and the United States, are proposing to remain on DST year-round. I’d prefer to remain on Standard Time and adjust the school bell times. For stargazers, advancing clocks by one hour, plus the fact that sunset occurs 1 minute later with each passing day near the March equinox, means that spring and summer star parties and dark-sky observing cannot begin until much later in the evening – usually after the bedtime of junior astronomers! Staying on DST will also mean that existing sundials will be permanently wrong because solar noon will occur at 1 pm, and not at 12 pm.

More Taurids Meteors

The Southern Taurids meteor shower, which reached its maximum last night (Saturday), will now taper off until December 2.

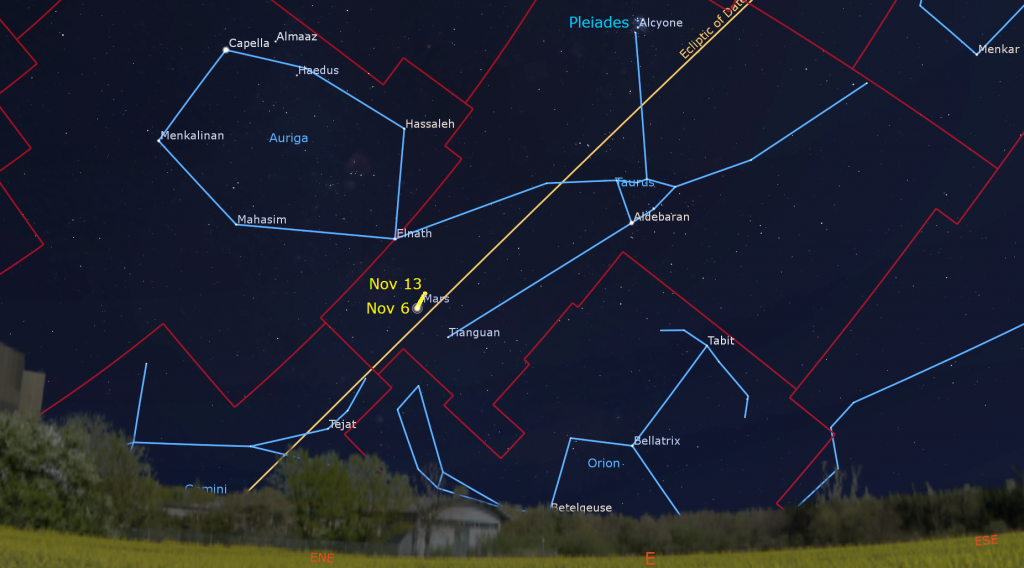

Meteors from the Northern Taurids meteor shower, which appear worldwide from October 20 to December 10 annually, will reach its own maximum on Saturday afternoon, November 12 in the Americas. Since meteors require a dark sky, the best viewing time for North American skywatchers will be off-peak – on Saturday morning before dawn and late on Saturday evening, November 13. At those times, the shower’s radiant near the Pleiades star cluster in Taurus will be well above the horizon in a dark sky.

The long-lasting, weak shower is the second of two consecutive showers derived from debris dropped by the passage of periodic Comet 2P/Encke. The larger-than-average grain sizes of the comet’s debris often produce colorful fireballs. The Northern Taurids shower typically delivers 5 meteors per hour at its peak period – but 2022 could see an upswing, according to the International Meteor Organization. At this year’s peak, a bright, waning gibbous moon will shine near the radiant, reducing the number of meteors we see.

The Moon

The moon will dominate the evening sky for most of this week. While stargazers typically stay indoors and watch movies while the moon is close to full, this one will deliver a silver lining!

As this week begins, the moon is nearly opposite the sun in the sky. So when the sun goes to bed around 5 pm for mid-northern latitude observers, the moon will toss off the covers and rise to shine over the eastern rooftops not long after that time! Tonight’s 98%-illuminated moon will overwhelm the faint stars of Pisces (the Fishes) that surrounds it. Jupiter will gleam to the moon’s upper right (or celestial west-southwest). Watch their separation widen every night this week.

When the moon rises late on Monday afternoon, it will be occupying Aries (the Ram), and only hours away from its full moon phase, which will occur on Tuesday morning at 6:02 am EST, 5:02 am CST, or 11:02 GMT. If you look closely at the moon on Monday evening, you should be able to tell that it’s not quite full. A thin sliver on its upper right edge will still be dark – making it lookslightly less than perfectly round. When the moon rises at sunset on Tuesday evening, that darkened sliver will have jumped to moon’s opposite, left-hand edge – because the moon’s angle from the sun will have changed from 175 degrees east of the sun, to 173 degrees west of it. Tuesday morning’s full moon will also deliver a pre-dawn total lunar eclipse! See below for the details.

The November Full Moon, traditionally known as the Beaver Moon or Frost Moon, always shines in or near the stars of Taurus and Aries. Indigenous groups have their own names for the full moons, which lit the way of the hunter or traveler at night before modern conveniences like flashlights. The Anishinaabe people of the Great Lakes region call this one Mnidoons Giizis Oonhg, the “Little Spirit Moon”, a time of healing. The Cree Nation of central Canada calls it Kaskatinowipisim, the “Rivers Freeze-up Moon”, when the lakes and rivers start to freeze. The Haudenosaunee Confederacy (Iroquois / Mohawk) of Eastern North America call it Kentenhko:wa, the “Time of Much Poverty Moon”.

From Tuesday evening onwards, the moon will wane in phase and rise later, allowing it to linger into the western morning sky, too. On Wednesday, the bright gibbous moon will start a journey through Taurus (the Bull). Starting around mid-evening on Thursday, look in the lower part of the eastern sky to see the bright, reddish dot of Mars positioned a palm’s width to the moon’s lower left. As the duo crosses the night sky together the moon’s eastward orbital motion will carry it closer to Mars, allowing them to share the view in binoculars. Early risers on Friday can watch for the moon and Mars shining in the western sky before dawn. By then, the diurnal rotation of the sky will have lifted Mars to the Moon’s upper left.

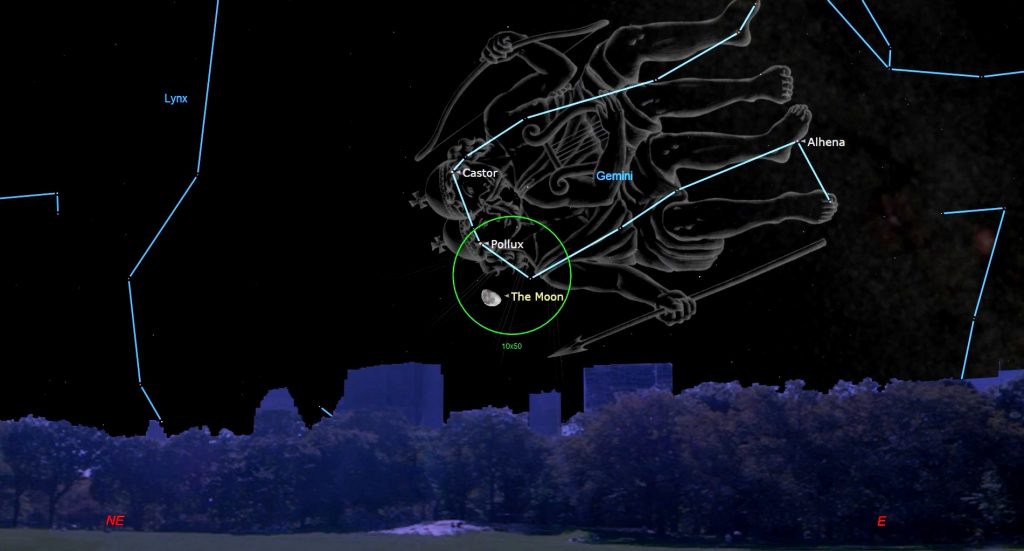

On Friday, the moon will rise at around 7 pm local time and shine near the toe stars of Gemini (the Twins). It will spend Saturday between those siblings. On Sunday night, the 72%-lit moon will be aligned with Gemini’s brightest stars Pollux and Castor. When the trio rises in the east during mid-evening, the moon will appear several finger widths below (or 3.5 degrees to the celestial southeast of) Pollux – close enough to share the view in binoculars. Somewhat less-bright Castor will shine above them. By dawn, the eastward orbital motion of the moon will carry it a little farther from Pollux and bend their alignment. Meanwhile, the diurnal rotation of the sky will pivot their line to horizontal.

Tuesday Morning’s Total Lunar Eclipse

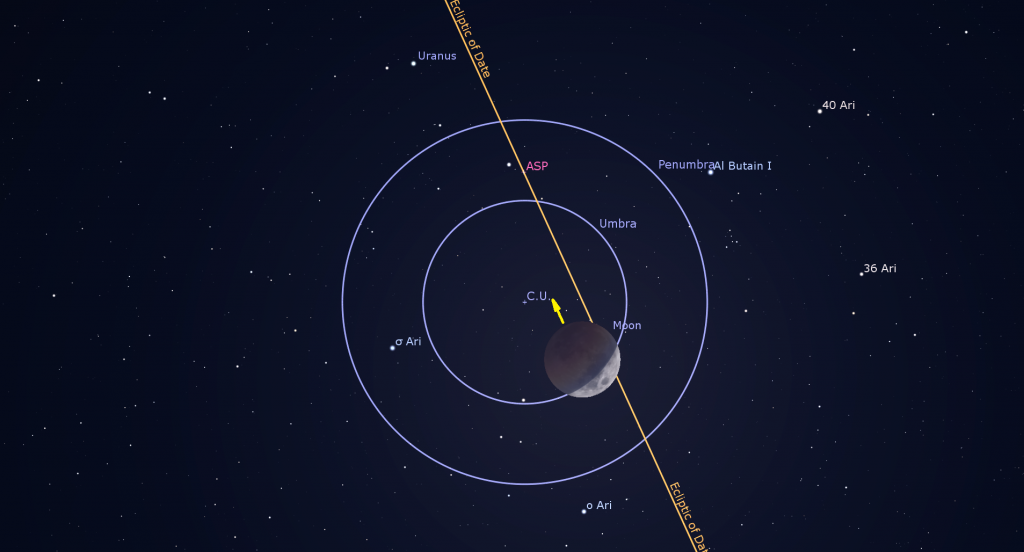

Because the Earth is a solid sphere with sunlight shining upon it, it casts a circular shadow into space that is opposite from the sun and close to the ecliptic. That black shadow is invisible against the black sky background. But if an object, such as the International Space Station or the moon, passes through it, Earth’s solid bulk will prevent the sunlight from reaching the object, and darken it. If you watch satellites on a clear, dark night, and note where in the sky they disappear (entering Earth’s shadow) or suddenly appear (exiting Earth’s shadow), you can trace out Earth’s shadow. It’s always there!

The zone where the sun is completely obscured by the Earth is called the umbra (that’s where the word “umbrella” – a sun shade – comes from). Surrounding this is a much larger circle called the penumbra, where some portion of the sun can still shine on an object. Objects passing through the penumbra will appear darkened, but still visible, for those of us on Earth.

The diameter of the shadowed region decreases as you move farther from Earth. At the moon’s distance, the umbra is about 1.25 degrees (or a thumb’s width) in diameter. The moon’s orbit is tilted by about 5 degrees compared to the ecliptic. That allows the moon to cross the ecliptic, and stray to the north and south of it by up to a palm’s width. Lunar eclipses occur whenever a full moon phase occurs while the moon is close enough to the ecliptic for it to dip fully or partly into Earth’s shadow. These alignments, or syzygys, of the sun, Earth, and moon happen 2 to 5 times per year.

If the moon completely enters the umbra, we see a total lunar eclipse. If part of the moon remains in the penumbra, we see a partial lunar eclipse. Either way, lunar eclipses are 100% safe to look at with unprotected eyes, both directly, and through binoculars – and to photograph. A telescope can even reveal the Earth’s shadow creeping across the moon’s surface in real time.

Earth’s atmosphere refracts (or bends) rays of sunlight because it slows the light down a little. Refraction allows sunlight to bend around the Earth’s horizon, letting some light reach even a fully eclipsed moon. The extra-long trip that sunlight must take while it skims through Earth’s blanket of air preferentially scatters away the shorter, bluer wavelengths, leaving the longer wavelength red light – turning the eclipsed moon reddish with sunset-coloured light, hence the nickname “blood moon”. If you could view the Earth from the surface of the moon during a total lunar eclipse, our dark globe would be encircled by a beautiful, narrow ring of reddish light!

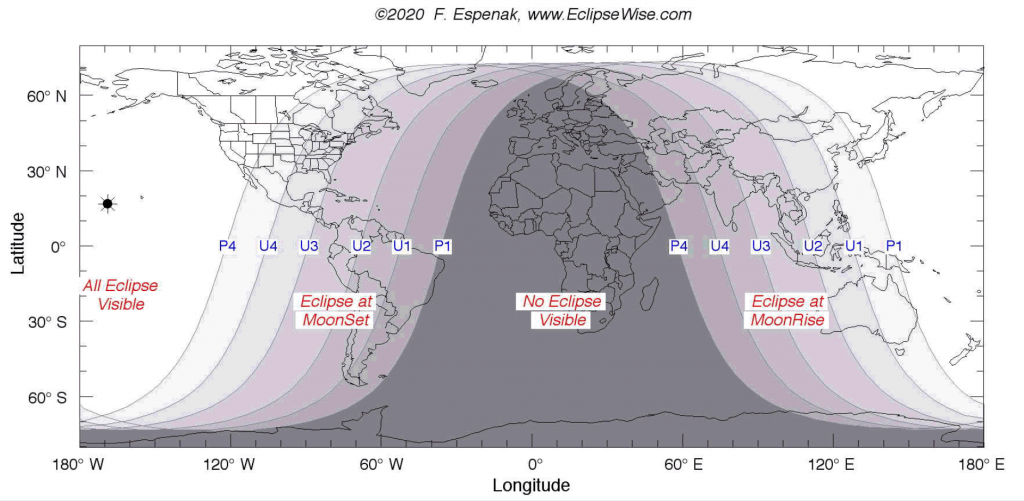

Tuesday’s full moon will produce the second total lunar eclipse of 2022! Unfortunately, this one will happen during the wee hours for much of the Americas. Any given lunar eclipse will be visible over about half the Earth’s globe. This entire eclipse will be visible across northwestern North America, the Pacific Ocean, and northeastern Asia. For the rest of North America, the moon will set while it is fully eclipsed. None of this eclipse will be visible from Africa or Europe.

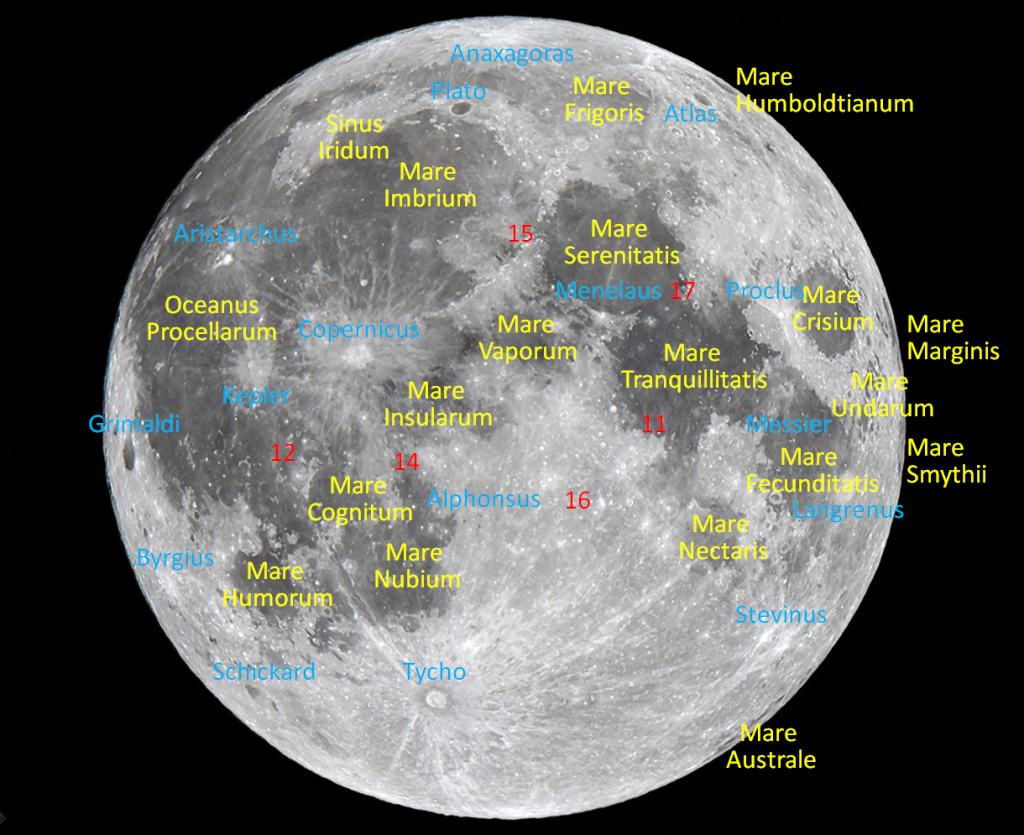

The moon moves east by about its own diameter every hour. At 3:02 am EST or 8:02 Greenwich Mean Time, the moon will first touch the edge of Earth’s penumbra. As it sinks deeper into it, the moon will darken very slightly. The moon will first contact the umbra at 4:08:49 am EST, or 9:08:49 GMT. That’s when you’ll begin to see the “bite” being taken out of the full moon – the beginning of the partial phase of the eclipse. The moon will be fully eclipsed for 85.66 minutes, shining with a deep red color between 5:16 am and 6:42 am EST (ending in twilight as the moon sets in the Eastern Time zone). That corresponds to from 3:16 am to 4:42 am MST, from 2:16 am to 3:42 am PST (where the moon will be nice and high in a dark sky), and from 10:16 to 11:42 GMT.

Around maximum eclipse at 5:59:11 am EST, 3:59:11 am MST, 2:59:11 am PST or 10:59:11 GMT, the moon’s northern edge will be passing through the outer reaches of Earth’s umbra, causing the southern part of the moon to be noticeably darker than the northern.

The moon will start to rebrighten when it moves beyond the umbra starting at 5:16:12 am EST. It will completely leave Earth’s umbra at 5:49:24 am MST or 11:49:24 GMT. The penumbral eclipse will end at 6:56:32 am MST, or 13:56:32 GMT. The lunar limb near the crater Langrenus will contact the shadow last.

During maximum eclipse, objects around the dimmed full moon, such as the nearby Pleiades Star Cluster, will return to their full glory. You do not need to drive to a special site to see this eclipse, but you will want to ensure that the moon won’t be blocked by buildings or trees, especially if you plan to photograph the stages of the event. In the Greater Toronto Area, the moon will be 30 degrees above the west-southwestern horizon when the partial phase begins, only 10 degrees above the western horizon at maximum eclipse. The eclipsed moon will be much higher in the sky if you live farther west. Check the weather forecast before setting your alarm, and let me know if you see it!

Around 12:00 GMT, observers in Asia, Alaska, and the Yukon can watch the partially-eclipsed moon occult the planet Uranus! The exact times vary by location. For Tokyo, the lunar occultation will run from 8:41 pm to 9:22 pm JST.

Details for any lunar or solar eclipse can be found at Fred Espenak’s terrific Eclipsewise.com site. His page for this eclipse is here. The Virtual Telescope Project, featuring some of my friends’ cameras, will start a livestream of the eclipse at 4:30 am EST (or 9:30 GMT) on Tuesday morning. Timeanddate.com will have a stream here, too.

Try to catch this eclipse if your weather allows it. The next total lunar eclipse for Canada will not be until March 14, 2025, when we’ll see another pre-dawn event with totality lasting from 2:26 am to 3:32 am Eastern Time.

The Planets

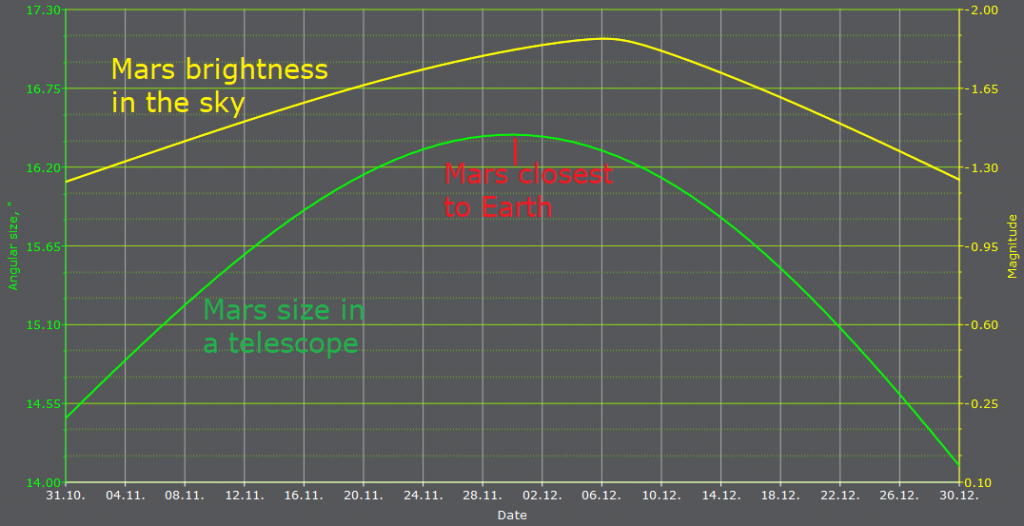

Mars is making its move in the evening sky worldwide! Over the next several weeks, Mars will dramatically swell in apparent size (in your telescope’s eyepiece) and ramp up in visual brightness in the sky (currently at magnitude -1.37) – all because Earth is passing the red planet on the inside track. The two planets’ minimum separation, which happens every 27.5 months, will occur overnight on November 30. This week, we’re 89 million km, or 4.9 light-minutes away, and closing.

The switch from Daylight Saving Time has made Mars much more accessible to northern hemisphere skywatchers. This week, the planet will be rising in the northeastern sky by about 7 pm in your local time zone – joining 3.5 times bright Jupiter and 7 times fainter Saturn off to its right (or celestial west). Mars’ rising time will shift earlier by 4-5 minutes each night. Next Sunday it will be up at 6:30 pm!

Mars is a terrific object to view in a backyard telescope when it gets this close. Planets look best when they are highest in the sky, since you’re then seeing them through less of Earth’s turbulent atmosphere. This week, Mars will climb highest, and sit due south, around 2 am local time – but any viewing during late evening will be nearly as good. Viewed in a telescope this week, Mars will show a waxing, 96%-illuminated disk. If the air is steady you might see some dark markings wrapping around the planet and the white patch of its northern polar cap. I posted a labelled Mars map here. If you have coloured filters for your telescope, see if the blue, orange, or red one improves the view.

Due to Earth’s faster motion, Mars is experiencing a westerly retrograde loop that will last through its December opposition and into mid-January. This week, Mars will be positioned between the two horn tips of the bull, composed of the medium-bright stars Zeta Tauri (the lower one) and Elnath or Beta Tauri (the higher one). Over the next month, you can watch Mars swing between those stars and then race west towards bright orange Aldebaran and the Pleiades star cluster. The bright moon will shine near Mars on Thursday night.

The extremely bright, magnitude -2.8 planet Jupiter will catch your eye as dusk arrives, when it will gleam in the lower part of the southeastern sky. Jupiter will climb highest in the sky (or culminate over southern horizon) shortly after 9 pm local time. Then it will set in the west around 3 am local time.

Any decent pair of binoculars will show Jupiter as a small disk flanked by its string of four Galilean moons named Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto. They complete orbits of the planet every 1.7, 3.6, 7.2, and 16.7 days, respectively. If you see fewer than four moons, then one or more of them is crossing in front of or behind Jupiter, or lurking in Jupiter’s dark shadow – or two of the moons are occulting one another. Their arrangement varies each night.

Use your binoculars to seek out a pentagon-shaped ring of stars shining about a fist’s diameter above Jupiter. They make up the western head of Pisces (the Fishes). All five stars should almost fit within your binoculars’ field of view. The brightest two stars are Iota Piscium (on the left) and Gamma Piscium (on the right). Those stars shine at about the magnitude limit that you can see without aid under suburban skies. The rest of Pisces forms a huge V of faint stars to Jupiter’s left (or celestial east).

A telescope can show you Jupiter’s dark belts and light bands, which are aligned parallel to its equator. Jupiter’s Great Red Spot, a cyclonic storm that has raged for hundreds of years, is visible for several hours when it crosses the planet. Because Jupiter rotates once every 10 Earth-hours, the GRS appears every 2nd or 3rd night. You can see it with a good quality backyard telescope. For observers in the Americas, that GRS will cross Jupiter’s disk in early evening on Sunday, Tuesday, Friday, and Sunday, late on Monday, Thursday, and Saturday evening, and during the wee hours of Tuesday, Thursday, and Sunday. If you have any coloured filters or nebula filters for your telescope, try enhancing the GRS with them.

The round, black shadows of Jupiter’s Galilean moons are visible through a good backyard telescope when they cross the planet’s disk. For observers in the America’s, Io’s shadow will cross Jupiter’s equator on Tuesday evening between 9:35 pm and 11:35 pm EST. On Wednesday evening, the small shadow of Europa will cross the southern hemisphere of the planet from 8:05 pm to 10:30 pm EST. From 11:25 pm to 2 am EST that same night, the much larger shadow of Ganymede will follow it. Don’t forget to adjust these quoted times into your own time zone.

The yellowish, medium-bright dot of magnitude 0.68 Saturn will join Jupiter once the sky darkens a little more – shining above the stars of Capricornus (the Sea-Goat). Saturn recently resumed its regular easterly prograde motion. In the coming months, it will slide to the left above the left-right pair of stars that form the sea-goat’s tail, Deneb Algedi (on the left, celestial east) and Nashira (on the right, celestial west). I plotted its path here.

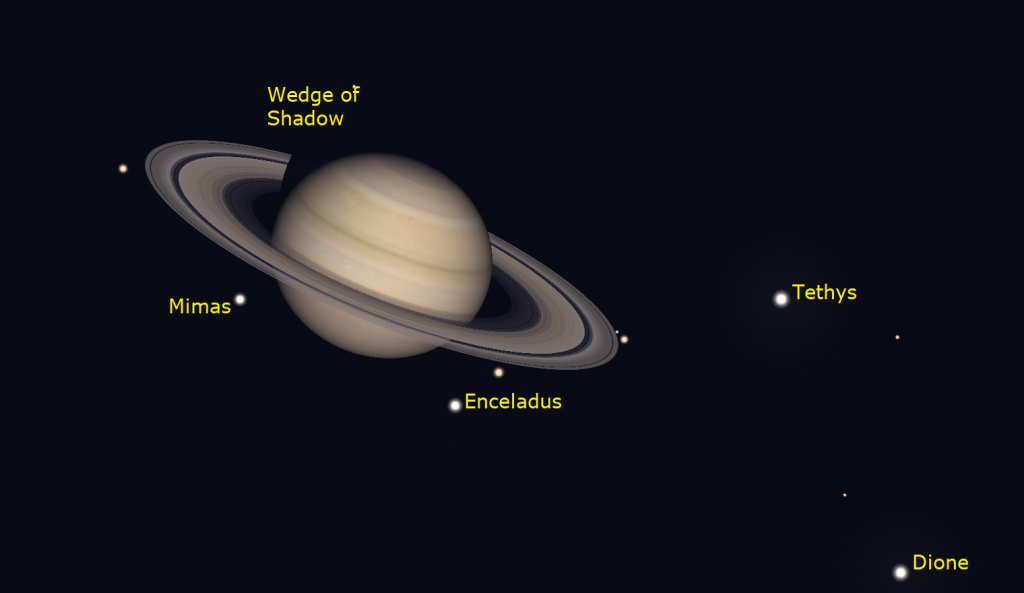

Saturn will be highest in the south at dusk, and then it will set in the west towards midnight. Very good binoculars should show Saturn and its rings as a tiny oval. On a good night, even a small telescope can show Saturn’s subtly banded globe encircled by its glorious rings, which are sufficiently edge-on to us to allow Saturn’s southern polar region to extend well beyond the ring plane. See if you can make out the Cassini Division, a narrow, dark zone that separates Saturn’s main inner ring (named B) from its bright outer ring (named A).

Saturn’s position far to the west of the anti-solar point has caused the planet’s globe to cast a widening wedge of dark shadow onto the rings where they emerge from behind the eastern limb of the planet. This week that wedge of shadow will reach its maximum size when Saturn is 90° away from the sun in the sky. Where you see that shadow will depend upon how your telescope flips and/or mirrors the view. In a refractor or SCT telescope, it’s toward the upper right. In a Newtonian reflector, it will be toward lower right. An equatorial mount will rotate the scene, too.

A small telescope can also show several of Saturn’s moons – especially its largest, brightest moon, Titan! From here on Earth, Saturn’s axial tilt of 26.7° lets us see the top of its ring plane, and allows its brighter moons to array themselves all around the planet. Titan never wanders more than five times the width of Saturn’s rings from the planet. The much fainter moon named Iapetus can stray up to twelve times the rings’ width during its 80-day orbit of Saturn. The next brightest moons Rhea, Dione, Tethys, Enceladus, and Mimas all stay within one ring-width of Saturn. During evening this week, Titan will migrate counter-clockwise around Saturn, moving from the right (or celestial west) of Saturn tonight (Sunday) to the left (or celestial east) of Saturn next Sunday. (Remember that your telescope might flip that view around.) How many of the moons can you see in your telescope?

Magnitude 7.8 Neptune is located a generous palm’s width to the right (or 7° to the celestial west-southwest) of Jupiter, which will slide a wee bit closer to the distant planet every night. Neptune’s apparent disk size is 2.4 arc-seconds (20 times smaller than Jupiter’s). Try for Neptune while it is highest, around 9 pm. I recently posted a finder chart for Neptune here.

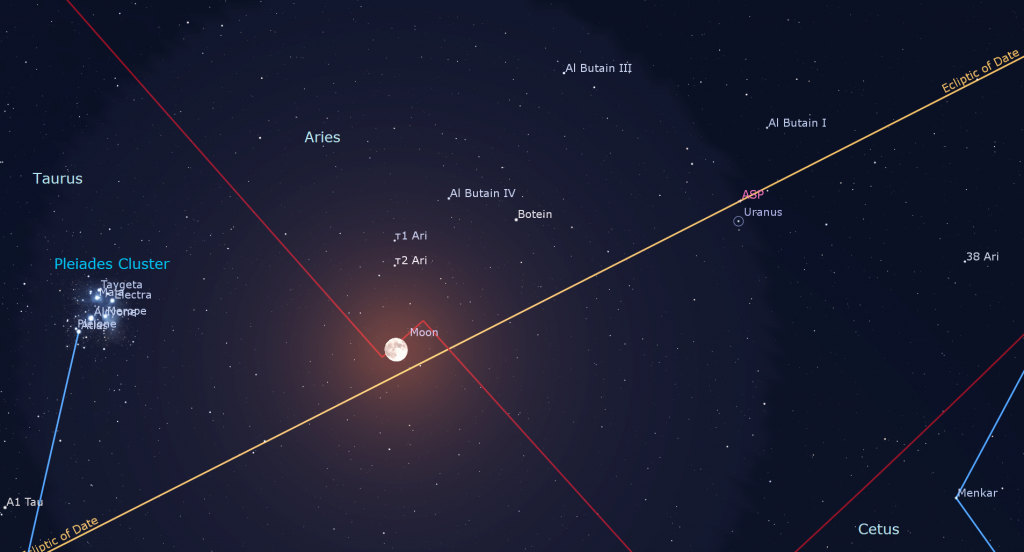

Uranus is located about midway between Mars and Jupiter, and about 1.3 fist widths to the upper right (or 13° to the celestial west-southwest) of the Pleiades star cluster. Closer guideposts to Uranus are several medium-bright stars named Botein (or Delta Arietis), Al Butain II (or Rho Arietis), and Sigma Arietis which will appear several finger widths from Uranus. Those stars mark the feet of the Aries (the Ram). The magnitude 5.7 planet will be high enough for telescope-viewing, in the lower part of the eastern sky, by 9 pm local time this week. Uranus will reach opposition on Tuesday night / Wednesday morning. At that time it will be closest to Earth for this year – a distance of 2.80 billion km, or 155 light-minutes. Uranus’ slightly reduced distance from Earth will cause it to shine at a peak brightness of magnitude 5.64 – but the recently full moon shining a palm’s width to Uranus’ left (or celestial east) will make seeing it difficult. Since Uranus will appear slightly larger in telescopes for a week or so centered on opposition night, view it on a night when the moon isn’t as close to it.

The large asteroids designated (4) Vesta and (3) Juno are currently between Jupiter and Saturn, too.

Public Astro-Themed Events

Every Monday evening, York University’s Allan I. Carswell Observatory runs an online star party – broadcasting views from four telescopes/cameras, answering viewer questions, and taking requests! Details are here. They host in-person viewing on the first clear Wednesday night each month. On Wednesdays they stream views online via the observatory YouTube channel. Details are here.

My free, family-friendly Insider’s Guide to the Galaxy webcasts with Samantha Jewett of RASC National returns on Tuesday, November 8 at 3:30 pm EST. RASC President Charles Ennis has been creating a catalogue of the star patterns employed by a myriad of cultures around the world. He’ll join us as a special guest to take us through his World Asterism Project and share his favorites. You can find more details and the schedule of future sessions here.

On Wednesday evening, November 9 at 6:30 pm EST, the International Issues Discussion (IID) series at Toronto Metropolitan University is proud to present its third virtual talk of the Fall 2022 term. Today’s Leading Space Issues will feature Dr. John M. Logsdon, Professor Emeritus of Political Science and International Affairs at George Washington University’s Elliott School of International Affairs. Details and the Eventbrite registration link are here.

On Thursday, November 10 at 7:30 pm EST, McMaster University’s Origins Institute will live stream a free talk by Dr. Ryan Cloutier titled The Long Path Towards Finding Habitable Exo-Worlds. Details and the Zoon registration link can be found here.

On Friday, November 11 at 8 pm EST, adults can enjoy some suds with their science at Astronomy on Tap T.O. at the Great Hall on Queen St. in Toronto. The free event hosted by the U of T Astronomy Department features talks, trivia, contest giveaways, and more! Details and the Eventbrite link are here.

RASC’s in-person sessions at the David Dunlap Observatory will soon be resuming! In the meantime they are pleased to offer some virtual experiences instead in partnership with Richmond Hill. The modest fee supports RASC’s education and public outreach efforts at DDO. Only one registration per household is required. Prior to the start of the program, registrants will be emailed the virtual program link.

On Saturday, November 12 from 6:30 to 8 pm EDT, the online DDO Astronomy Speakers Night program will feature Maheen Hemani, a student at York University’s Allan I Carswell Observatory. She’ll speak on Astronomical Research at the Undergraduate Level. There will also be a virtual tour of the DDO and live-streamed views from the DDO’s 74-Inch telescope (weather permitting). The deadline to register for this program is Wednesday, November 9, 2022 at 4 pm. More information is here and the registration link is here.

On Sunday, November 13 from 12:30 to 1 pm EDT, tune in for DDO Sunday Sungazing. Safely observe the sun with RASC, from the comfort of your home! During these family-friendly sessions, a DDO Astronomer will answer your questions about our closest star: the sun! Learn how the sun works and how it affects our home planet. Live-streamed views of the sun through small telescopes will be included, weather permitting. Only one registration per household is required. Deadline to register for this program is Wednesday, November 9, 2022 at 3 pm. More information is here and the registration link is here.

On Monday, November 28 from 8 to 9:30 pm EST, Blake Nancarrow, Chair of the RASC Observing Committee, will present a free, public online webinar during which he will introduce and demonstrate the popular and powerful, and free! Stellarium astronomy program. No prior experience is necessary. Details and the Zoom registration link can be found here.

Keep looking up, and enjoy the sky when you do. I love questions and requests. Send me some!