Inner Planets after sunset, the Pretty Moon Slips Over Evening Spica, and the Summer Milky Way Hosts Peak Ceres!

This image from the Wide Field Imager attached to the MPG/ESO 2.2-metre telescope at ESO’s La Silla Observatory shows the spectacular globular star cluster Messier 4. This great ball of ancient stars is one of the closest of such stellar systems to the Earth and appears in the constellation of Scorpius (The Scorpion) close to the bright red star Antares.

Here are your Astronomy Skylights for the week of July 7th, 2024 by Chris Vaughan. Feel free to pass this along to your friends and send me your comments, questions, and suggested topics. You can also follow me on Twitter as @astrogeoguy! Unless otherwise noted, all times are expressed in Eastern Time. To subscribe to these emails please click this MailChimp link.

If you’d like me to bring my Digital Starlab portable inflatable planetarium to your school or other daytime or evening event in Simcoe, Grey, and Bruce Counties, or deliver a virtual session anywhere, contact me through AstroGeo.ca, and we’ll tour the Universe, or the Earth’s interior, together! My book with John A. Read entitled 110 Things to See With a Telescope is a guide to viewing the deep sky objects in the Messier List – for both beginners and seasoned astronomers. DM me to order a signed copy!

The moon will linger longer and grow brighter in the evening sky this week, making it a wonderful object of your attention. Before that, however, we can grab our binoculars and peruse the many sights to see in the summer Milky Way. On Saturday, the moon will occult the bright star Spica. The inner planets join the post-sunset sky, while Saturn holds court after midnight and Jupiter-Mars shine before sunrise. Read on for your Skylights!

The Moon

This will be the best week of the lunar month to enjoy views of our planet’s partner, worldwide. The moon will shine after dusk every evening while it coasts away from the sun and waxes in illuminated phase – gradually stealing the summer Milky Way by brightening the sky.

The moon is spherical, and its sunward hemisphere is always lit up (except during lunar eclipses). On the evenings after the moon has passed the sun at new moon, the moon is still more or less between Earth and the sun, so the lunar hemisphere that is lit up is the one facing away from Earth, and the “Dark Side of the Moon” is the side we are seeing! As the angle between the moon, you, and the sun increases, that lit hemisphere migrates more and more onto the Earth-facing side. We see that as the illuminated crescent growing thicker each evening. Once that moon-you-sun angle passes 90° the moon looks gibbous. When that angle reaches 180°, the moon is opposite from the sun in our sky and shines fully lit.

The border between the dark and lit hemispheres is called the terminator. Along that zone the sun is either rising or setting on the moon, so the sunlight striking the moon there is nearly horizontal. The two ends of the terminator, the “horn tips” of the crescent, are at the moon’s north and south poles. If you imagine a straight line connecting the two horn tips, you’ll notice that that line leans one way when the moon is rising in the east, it is vertical when the moon is due south, and it leans the other way while the moon is sinking in the west. That rotation isn’t happening because the moon is tipping. It happens because your whole body is tilting as you look up at the sky while you ride on the rotating ball of the Earth. (Planets and constellations tip the same way through the night.)

The sunlit side of the terminator line is spectacular under magnification. Every bump casts inky black shadows to its west, enhancing subtle terrain features. Since the terminator is constantly in motion as the moon orbits continuously around the Earth, the plays of light and shadow alongside the terminator vary hour-by-hour and night after night. Keep your binoculars (of any size) and backyard telescope ready to carry outside for a look.

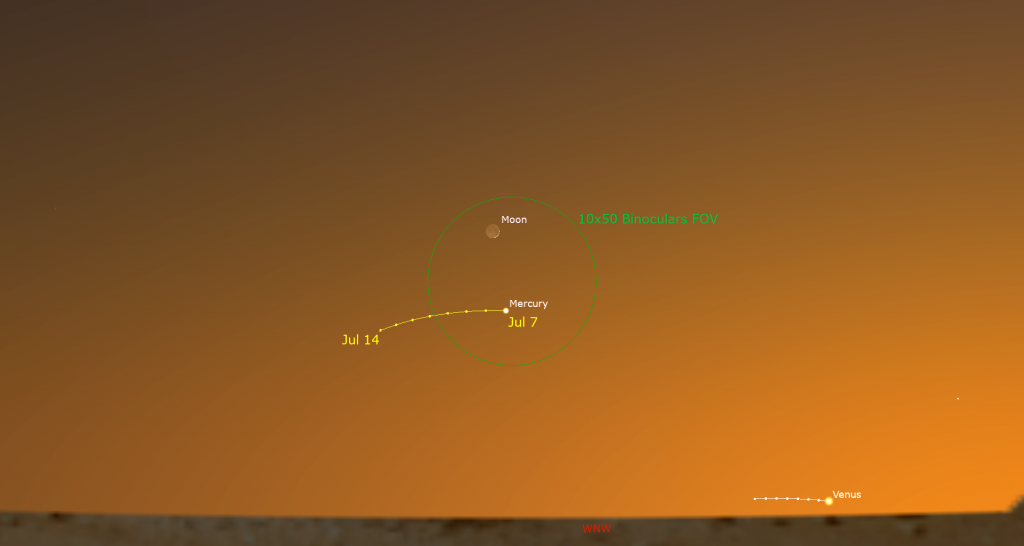

Tonight (Sunday), the extremely thin crescent moon will shine above the west-northwestern horizon for a short time after sunset. The dot of Mercury will be positioned a generous thumb’s width below (or 2.5 degrees to the celestial southwest) of the moon – easily close enough for them to share the view in binoculars. For eye safety, don’t aim optics in that direction until after the sun has completely set.

From Monday onward the moon will climb higher and linger longer into the evening, making it easier to see. Watch for Earthshine, also known as the Ashen Glow and “the old moon in the new moon’s arms”. That’s sunlight reflected off Earth and back toward the moon, slightly brightening the dark portion of the moon’s Earth-facing hemisphere. The phenomenon appears for several days after each new moon. Monday’s moon will shine in Leo (the Lion). Its brightest star Regulus will sparkle to the moon’s upper left.

On Tuesday, the moon will hop to Regulus’ upper left (or celestial east). On Wednesday, the moon will be sufficiently lit (24%) to spot it in the daytime sky. It will rise in late morning and then follow the sun across the sky until the lion’s stars appear around it after sunset.

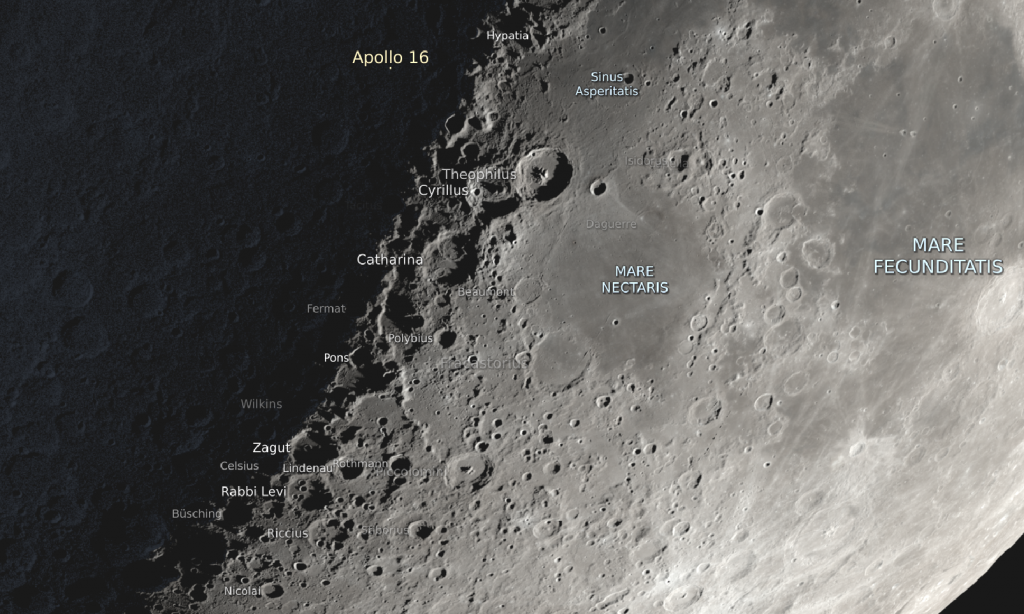

The waxing moon will spend the rest of this week gliding through the lengthy constellation of Virgo (the Maiden). On Thursday evening, the terminator will fall just to the left of a connected trio of large craters named Theophilus, Cyrillus, and Catharina that curve along the western edge of gray Mare Nectaris. You can tell what order the craters were formed in by observing how sharp and fresh Theophilus’ rim appears, and by the way it has partially overprinted neighboring Cyrillus to its lower left (or lunar southwest). Under magnification, Theophilus’ terraced rim and craggy central mountain peak are evident. Cyrillus hosts a trio of degraded central peaks inside a hexagonal rim (craters aren’t always round!), while much older Catharina’s peak has been submerged, her edges blurred and her floor overprinted by smaller, more recent craters.

The moon will complete the first quarter of its orbit around Earth, as measured from the previous new moon, on Saturday, July 13 at 6:49 pm EDT or 3:49 pm PDT and 22:49 Greenwich Mean Time. The 90° angle formed by the Earth, sun, and moon at that time will cause us to see our natural satellite half-illuminated on its eastern side and divided by a straight-line terminator. (The way the terminator curved, then straightened at first quarter, and then curved the opposite way afterwards told ancient astronomers that the moon was a sphere.)

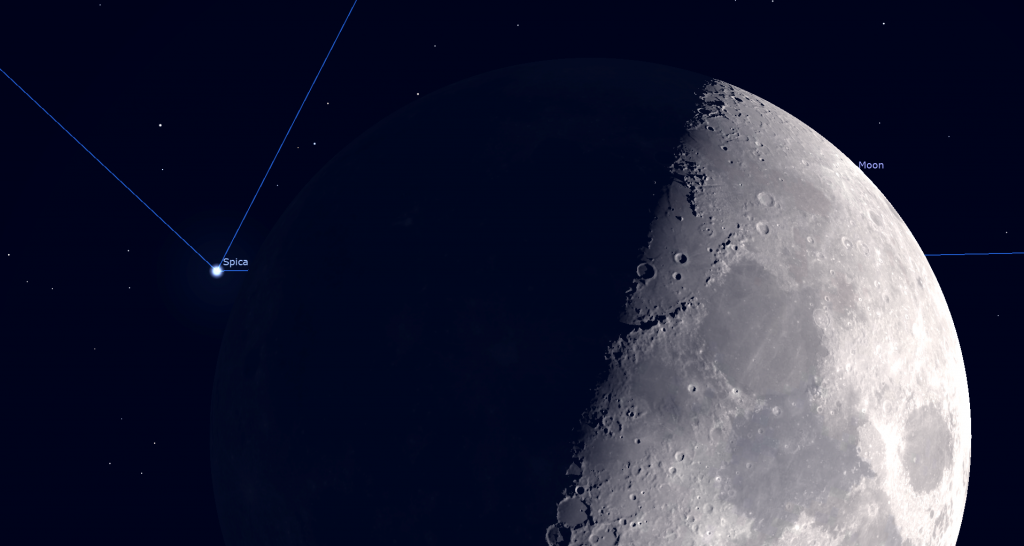

Thursday’s moon will also be shining very closely to the right (celestial west) of Virgo’s brightest star Spica. For observers across North and Central America, the Caribbean, and west to the eastern tip of Russia, the moon will pass in front of, or occult, Spica, after dusk. In the Eastern Time Zone, the dark, leading edge of the moon will begin to occult Spica just before they set in the west. Observers in the Central and Mountain Time Zones will see the entire occultation in a dark sky. For those located even farther west, the event will occur in a bright sky. Lunar occultations of bright stars can be seen with sharp, unaided eyes in a dark sky, and through binoculars and backyard telescopes – even when the sky is bright. Exact times for this event depend on your location, so use an app like Stellarium to look up your circumstances. You can also use the app to simulate where on the lit half of the moon the star will re-appear. In Toronto, Canada, the dark limb of the moon will cover Spica at 11:15 pm EDT. The star will emerge near Mare Crisium at 12:23 am EDT, as the moon is setting.

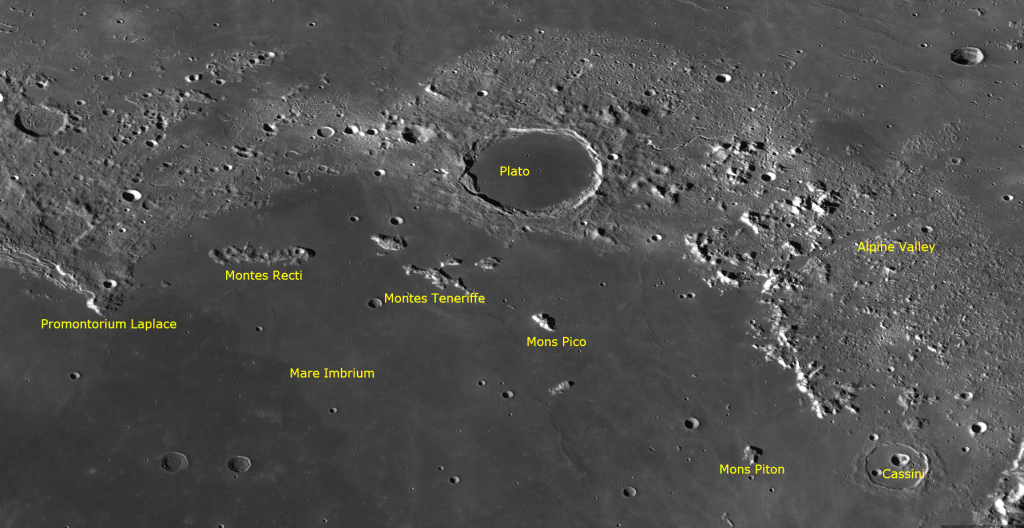

Next Sunday night, the terminator will pass north-south through the large and circular Imbrium Basin. Use any size of telescope to look for sinuous wrinkle ridges slithering over the seemingly flat floor of that large mare. The three spectacular and tall mountain ranges that ring the eastern half of the basin will still look spectacular. The dark, round, and smooth crater named Plato will break up the northern arc of the Alpine Mountains. A curving chain of little mountain peaks will poke out of Imbrium’s gray floor below Plato. Those include Montes Recti, Montes Teneriffe, and the single peaks of Mons Pico and Mons Piton. At the southern edge of the big circle, the Apennine Mountain range sinks almost out of sight after it passes the peaked crater Eratosthenes.

Touring the Dark Southern Sky

Before the moon gets bright late this week, let’s grab bug spray and binoculars, or dust off the old telescope, and set up in a spot with a low and open southern horizon for a tour through the scorpion, the teapot, and the shield!

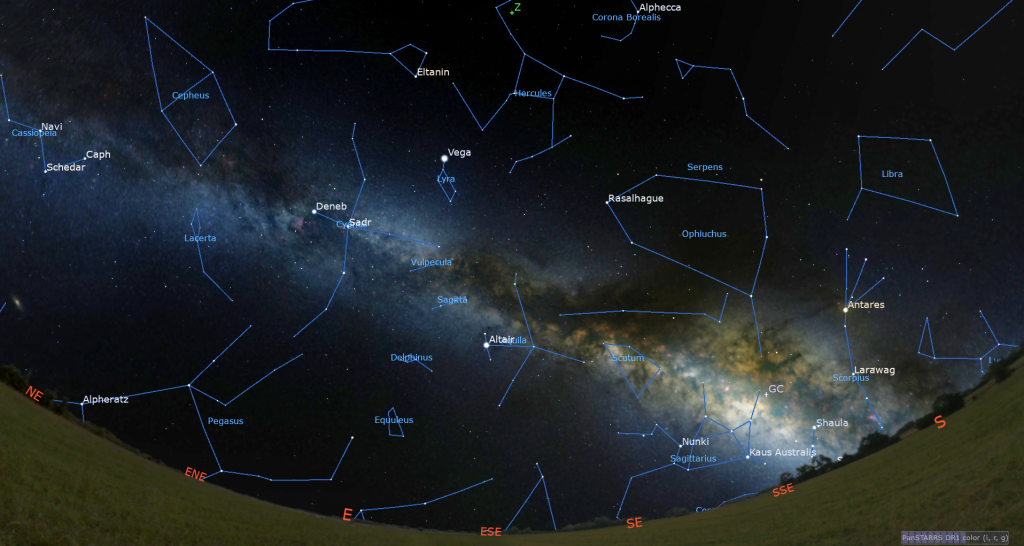

Once it’s getting nice and dark, face south and look for the Milky Way rising from the southern horizon. The brightened strip that forms the broad band of the Milky Way is the projection of our home galaxy’s disk-like plane on the night sky. It is composed of countless stars that are too far away to pick out individually by eye – but a good telescope will resolve many of them into a speckled backdrop. Humans from many cultures have long thought that this feature of the night sky resembled spilled milk. The Greeks called it galaxias, or “the milky vault”. Once humans discovered what the Milky Way glow actually was, we assigned the same word to all the other “islands of stars” in the Universe!

For mid-northern latitude observers, the Milky Way arcs overhead in the late-night summer sky. Due to haziness near the horizon, and more of Earth’s intervening atmosphere, the portion of the Milky Way higher in the sky, where it passes directly through Cygnus (the Swan), is easier to see. Around midnight local time, the great swan will be nearly overhead. The rest of the Milky Way descends to the northeast, thinning as it passes through the “W” of Cassiopeia (the Queen) and Perseus (the Hero) because that area represents the outer edge of our galaxy’s disk.

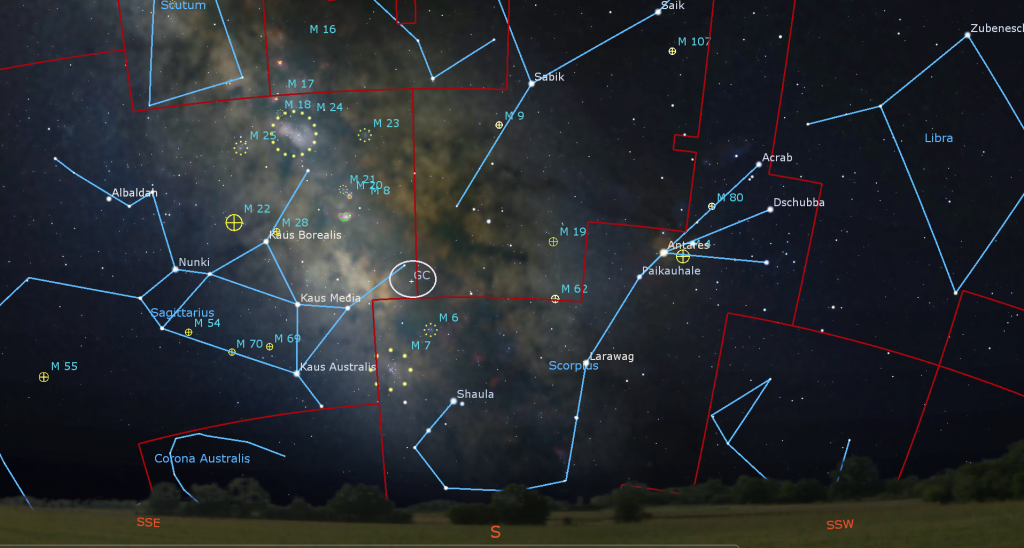

The centre of our galaxy, where lurks a supermassive black hole, is located near the place where the borders of the constellations Sagittarius (the Archer), Ophiuchus (the Serpent-Bearer), and Scorpius (the Scorpion) meet. For mid-northern latitude observers, the spot migrates to above the southern horizon only in evening from July to September. Folks in the tropics and the Southern Hemisphere see much more of our galaxy. In fact, some of the best sights in the sky are only visible from there!

Opaque interstellar dust concentrated in our galaxy’s plane obscures the stars beyond it. When you are tracing out the Milky Way on a dark, moonless night, watch for dark patches in Sagittarius and Scutum (the Shield), and long lanes of darkness that divides the way into two bands through Aquila and Cygnus.

Let’s highlight some of the best sights in the Milky Way. The distinctive constellation of Scorpius (the Scorpion) reaches its peak elevation over the southern horizon around 11 pm local time in late July. That constellation’s brightest star is orange-tinted Antares, the “Rival of Mars”. Three white, medium-bright stars aligned in a roughly vertical line to the right (or celestial west) of Antares mark the creature’s claws today – however the major stars of neighboring Libra (the Scales) used to play that role. The rest of the scorpion extends to the south, curling eastward into the Milky Way, and terminating in a bright double star named Shaula, which marks the poisonous stinger. The leftmost, easterly star, also known as Lambda Scorpii, is twice as bright as the other star, Upsilon Scorpii. Some people call them the Cat’s Eyes. Observers above mid-northern latitudes will struggle to see the southerly stars of this constellation. For Moana fans, the Maori of New Zealand consider those same stars to represent Maui’s fishhook pulling the Milky Way out of the sea every night!

For contrast with cool, reddish Antares, look at the two hot, white stars that flank the red supergiant. Magnitude 3.1 Al Niyat I (also known as Sigma Scorpii) is located 2 finger widths to the upper right (celestial northwest) of Antares. It is a B1-class star with a surface temperature of 36,200 K. The magnitude 2.8 star Tau Scorpii is located 2.25 degrees to the lower left (southeast) of Antares. Also known as Paikauhale, it is a B0-class star with a surface temperature of 30,000 K. At 734 light-years from the sun, Al Niyat I is nearly twice as far away as Tau. Use binoculars to find a fuzzy patch that is sitting just a finger’s width to Antares’ right. It is a globular star cluster named Messier 4 and it is huge in a telescope!

July evenings bring us another one of the best asterisms in the sky, the Teapot in Sagittarius (the Archer). This informal star pattern features a flat bottom formed by the stars Ascella on the left and Kaus Australis on the right, a triangular pointed spout pointing right, marked by the star Alnasl, and a pointed lid marked by the star Kaus Borealis. The stars Nunki and Tau Sagittarii form its handle. The asterism is low in the sky, but it reaches maximum height above the southern horizon around midnight local time, when it will look as if it’s serving its hot beverage – with the steam rising as the Milky Way. By the way – the centre of our galaxy is located just 4.5 finger widths to the upper right of Alnasl!

Next, use your binoculars to explore the rich star fields and nebulae sprinkled along the Milky Way above Sagittarius. The bright star clusters known as Ptolemy’s Cluster (also designated Messier 7), the Sagittarius Star Cloud (Messier 24), and Messier 25 will appear as compact, bright, white clouds in binoculars. You can also look for the bright knots of nebulosity comprising the Lagoon Nebula (Messier 8), the Omega / Swan Nebula (Messier 17), and the Eagle Nebula (Messier 16). Higher up, you’ll discover more good clusters, including Messier 39 and Messier 29 in Cygnus, Caldwell 16 in Lacerta (the Lizard), the Wild Duck Cluster (Messier 11) and Messier 26 in Scutum (the Shield). Use your backyard telescope for a closer look at them!

Scutum (the Shield) was created by Johannes Hevelius in 1683 by stealing some of the stars from next-door Aquila (the Eagle). The small constellation (84th out of 88, by area) occupies some prime celestial real estate along the summertime Milky Way. Scutum, which reaches its highest position over the southern horizon at midnight local time in late July, has a background of rich star fields, which are overlain by some fine open star clusters, including the aforementioned Wild Duck Cluster. Use binoculars to trace out the dim stars that form the constellation and then follow up with your telescope.

The Planets

If you are careful to wait until the sun has fully set, you can use binoculars to seek out both Venus and Mercury above the west-northwestern horizon on any evening this week. The key will be to have an unobstructed view that is free of clouds and excessive haze. Luckily, I saw both planets last night (Saturday). As I mentioned above, the young crescent moon will pose above Mercury tonight (Sunday). They’ll get easier to see through this week.

Venus will appear above the spot on the horizon where the sun disappeared. It will set about 40 minutes after the sun. At mid-northern latitudes, the best time to look will start at about 9:15 pm local time. Don’t worry if you miss it, though – Venus will be our brilliant “Evening Star” throughout this Fall/Winter. That time will also be good to begin looking for Mercury, which will be easier to see as the sky darkens. Mercury will be located a generous fist’s diameter to Venus’ upper left, even after the moon has left them behind. Each night, both planets will migrate a little to the left as they travel eastward across Cancer (the Crab). Mercury will step into next-door Leo (the Lion) next Sunday evening.

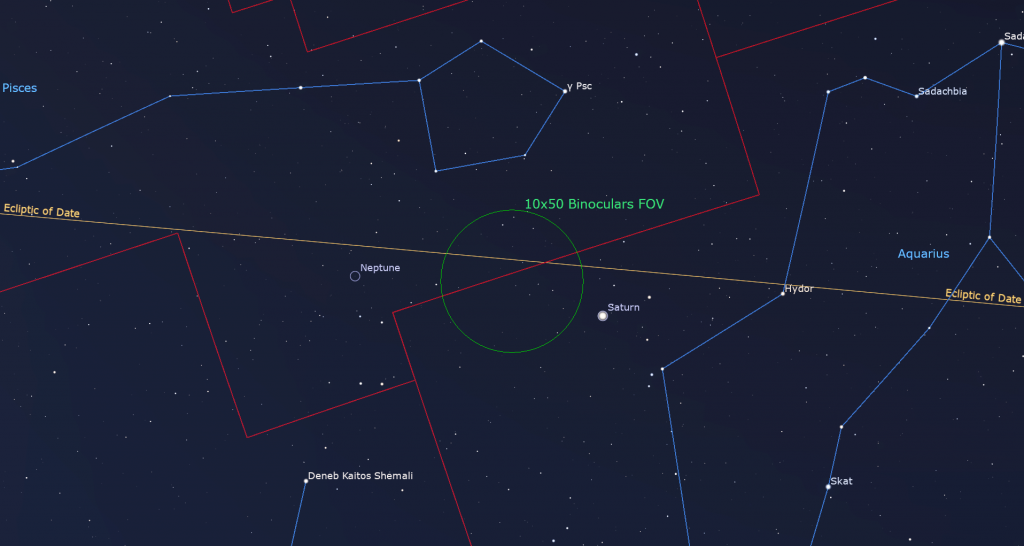

Next up, literally, will be Saturn. For everyone around the latitude of Toronto, the ringed planet will rise at about 11:45 pm local time. That time will advance by 30 minutes earlier each week. Saturn will spend the next 10 months among the stars of eastern Aquarius (the Water-Bearer).

Saturn’s rings, which will effectively disappear when they become edge-on to Earth next March, already look very narrow against the planet’s globe. Good binoculars can hint at Saturn’s rings, and any telescope will show them to you. For telescope-owners, Earth’s perspective of the Saturn system this year and next will cause its moons to align in the plane of the rings and produce frequent transits of Saturn’s moons and their black shadows across its disk.

Saturn recently started a retrograde loop westward across the stars of Aquarius (the Water-Bearer) that will last until mid-November. The apparent reversal in Saturn’s motion is an effect of parallax produced when Earth, on a faster orbit, passes the ringed planet on the “inside track”. You can observe the planet’s motion by noting how Saturn’s distance from the bright star to its right named Hydor (aka Lambda Aquarii) varies over the coming weeks. The outer planets are brighter and shine at convenient times during their retrograde periods.

Neptune will rise about 25 minutes after Saturn and follow it across the sky every night. Neptune also commenced its own retrograde loop last week. The remote, blue planet will spend this year in western Pisces (the Fishes), a generous fist’s width to the lower left (or 11° to the celestial ENE) of Saturn. Neptune will also be located a bit more than a thumb’s width to the upper left (or 2° north) of a medium-bright star named 27 Piscium, allowing them to share the view in binoculars. Other less-brilliant stars nearby named 29 Piscium, 24 Piscium, and 20 Piscium will help guide you to Neptune with a backyard telescope or good, strong binoculars. For now, you’ll need to look at Neptune while it’s higher and the sky is dark between about 1:30 and 4:30 am local time.

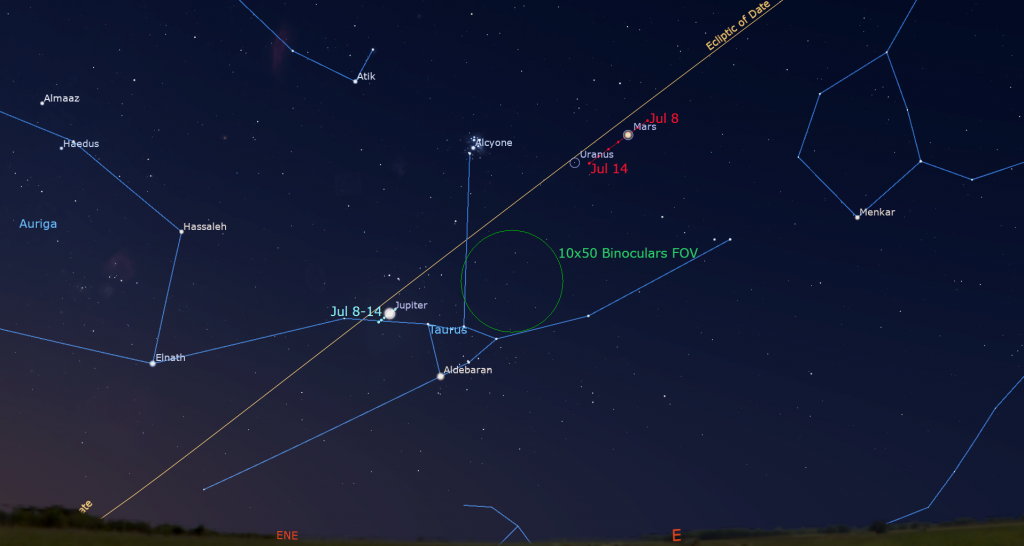

Reddish Mars will rise by 2:10 am local time and remain in sight until dawn. If you head out while the sky is still dark, the brightest stars of Aries (the Ram) and Perseus (the Hero) will twinkle well above it. Mars will appear to be very slightly brighter than Saturn. In a telescope, Mars will display a small, rusty-coloured disk. Its position on the far side of the sun from Earth will keep the planet looking small until later this year. While everything else rises earlier each week as the sky shifts west due to Earth’s motion around the sun, Mars is traveling in the other direction, like a fish suspended in a moving river. That’s why Mars isn’t yet rising much earlier.

Uranus will rise after Mars at about 2:20 am, and climb high enough to deliver reasonably clear views in a telescope for a short time before the brightening sky overwhelms it. To aid in your search, seek out the pretty, prominent Pleiades star cluster in your binoculars. Uranus will be positioned a palm’s width to its right. The cluster and planet will join the evening sky in September. Mars’ limited eastward motion is carrying it towards Uranus. They’ll be closest next Monday, but already cozy enough to share the view in a backyard telescope next Sunday.

Brilliant Jupiter is visible in the eastern pre-dawn sky from the time it rises around 3 am local time, until sunrise. Look out for the bright reddish star Aldebaran in Taurus (the Bull) shining to Jupiter’s lower right. From time to time, observers with good quality telescopes can watch the small, round, black shadows of the Galilean moons travel across Jupiter’s disk. On Saturday morning, July 13, sky-watchers located in western North America can watch two shadows cross the southern hemisphere of Jupiter, one after the other. At 2:49 am PDT (or 09:49 GMT), the small shadow of Europa will begin to cross Jupiter’s south polar zone. As it is leaving Jupiter’s disk at 5:10 am PDT (or 12:10 GMT), Io’s larger shadow will begin its own crossing. By the time its trip is complete, around 7:19 am PDT (or 14:19 GMT), the sky will be brightening.

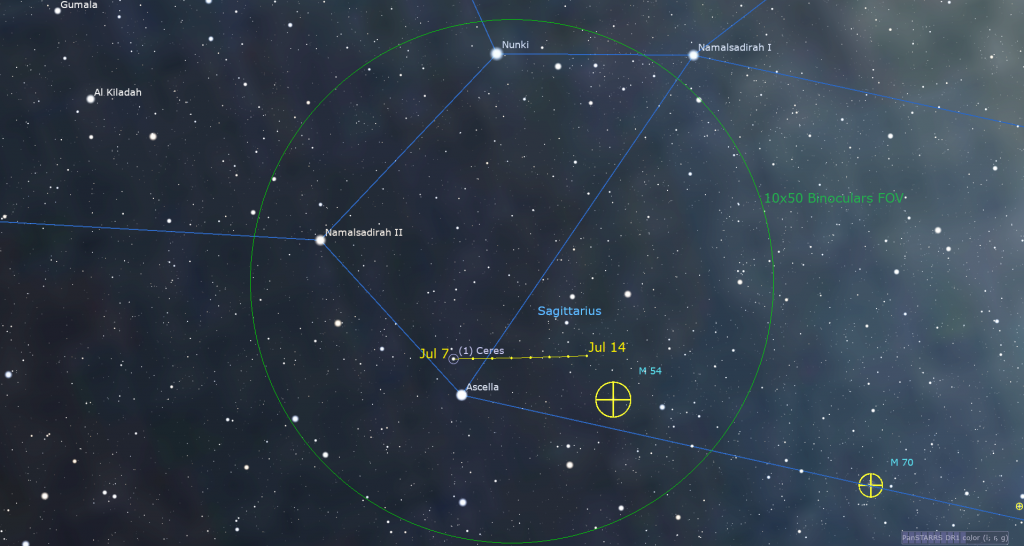

Several days ago, the dwarf planet Ceres reached opposition, its closest approach to Earth for the year. This largest resident of the main asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter is shining with a visual magnitude of 7.4, which is within reach of binoculars and backyard telescopes. Ceres is currently located in the lower left part of the Teapot-shaped asterism in Sagittarius (the Archer). It will begin this week above the bright star Ascella and then shift to the right nightly, ending this week above the nice globular star cluster named Messier 54 (aka NGC 6715). Ceres will ascend the southeastern sky after dusk, and then reach its highest elevation, and peak visibility, when due south around 1:20 am local time. It will spend the rest of July travelling west through the Teapot.

Hercules on High

If you missed last week’s tour of the constellation of Hercules, I posted it here.

Public Astronomy-Themed Events

Every Monday evening, York University’s Allan I. Carswell Observatory runs an online star party – broadcasting views from four telescopes/cameras, answering viewer questions, and taking requests! Details are here. They host in-person viewing on the first clear Wednesday night each month. Other Wednesdays they stream views online via the observatory YouTube channel. Details are here.

Taking advantage of the crescent moon in the sky this week, the RASC Toronto Centre astronomers will hold their monthly City Sky Star Party in Bayview Village Park (a short walk from the Bayview TTC subway station), starting after dusk on the first clear weeknight this week (Mon, Tue or Thu only). Check here for details, and check the banner on their website home page or Facebook page for the GO or NO-GO decision around 5 pm each day.

Eastern GTA sky watchers are invited to join the RASC Toronto Centre and Durham Skies for solar observing and stargazing at the edge of Lake Ontario in Millennium Square in Pickering on Friday evening, July 12, starting at 7 pm. Details are here. Before heading out, check the RASCTC home page for a Go/No-Go call – in case it’s too cloudy to observe.

Keep your eyes on the skies! I love getting questions and requests. Send me some!