Lunar Lighting Explained, the Moon Meets the Scorpion, a Modest Meteor Shower, and Planets Populate the Night!

This simulated 3D model of the solar system shows the position of Earth on July 30 while it is crossing through the debris field dropped along the orbit of comet P/2008 Y12 (SOHO), producing the peak of the Southern Delta-Aquariids Meteor Shower. You can manipulate the model at the website https://www.meteorshowers.org/

Hello, Summer Stargazers!

Here are your Astronomy Skylights for the week of July 23rd, 2023 by Chris Vaughan. Feel free to pass this along to your friends and send me your comments, questions, and suggested topics. You can also follow me on Twitter as @astrogeoguy! Unless otherwise noted, all times are expressed in Eastern Time. To subscribe to these emails please click this MailChimp link.

If you’d like me to bring my Digital Starlab portable inflatable planetarium to your school or other daytime or evening event, or deliver a session online, contact me through AstroGeo.ca, and we’ll tour the Universe, or the Earth’s interior, together! My terrific book with John A. Read entitled 110 Things to See With a Telescope is a guide to viewing the deep sky objects in the Messier List – for both beginners and seasoned astronomers. DM me to order a signed copy!

The waxing moon will continue its residence in the evening sky this week. I explain why the moon is missing sometimes, share some more information about the Southern Delta Aquariids meteor shower, and we bid farewell to Venus after sunset and welcome Jupiter to the late night sky. Read on for your Skylights!

The Moon

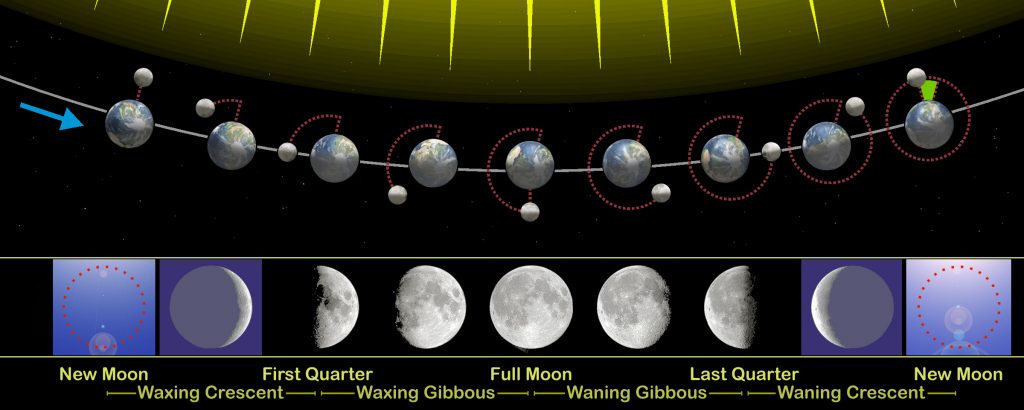

Everyone on Earth sees the same moon phase, though at times we need to wait for the Earth to rotate enough to place the moon above the horizon for our longitude/time zone. The way the moon looks to Earth-bound viewers depends on how it’s being illuminated at any given time, and that is dictated by the moon’s angle from the sun in the sky. When the moon’s orbit carries it through the space between us and the sun at new moon, no sunlight can directly reach the side of the moon facing Earth, and the sun’s glare hides objects near it, anyway. So the moon isn’t visible from anywhere on Earth – unless there’s a solar eclipse! Many cultures have adopted the “missing moon” day as the start of a new month.

While new, the moon is positioned less than about 12 degrees from the sun, in the pre-dawn east on the day before new and then in the post-sunset west on the day after. The rest of the time we can see the moon during at least some part of the day or night. It might linger only for a short time after sunset, rise in mid-day and then shine in evening, appear as the sun is setting and shine all night long, or rise in the morning before the sun, making it completely absent for stargazers who only venture out in evening or late night. The moon’s dance towards and away from the sun repeats every 29.53 days, or about a month. That’s why “moon” and “month” are similar words.

The moon’s phases are tied to the times of day I just described. Whenever the moon is in the afternoon and evening sky, it is waxing in phase – starting as a thickening crescent for about a week, appearing half-full at first quarter, and then showing a gibbous shape in the week before it’s full. Full moons shine all night long. After full moon night, the moon wanes in phase, showing as gibbous again in late night and early morning for about a week. It will appear half-full at third quarter, when it rises around midnight and sets towards noon. Finally, the moon will revert to a slimming crescent in the eastern pre-dawn sky for the week leading to new moon. And then the dance begins again.

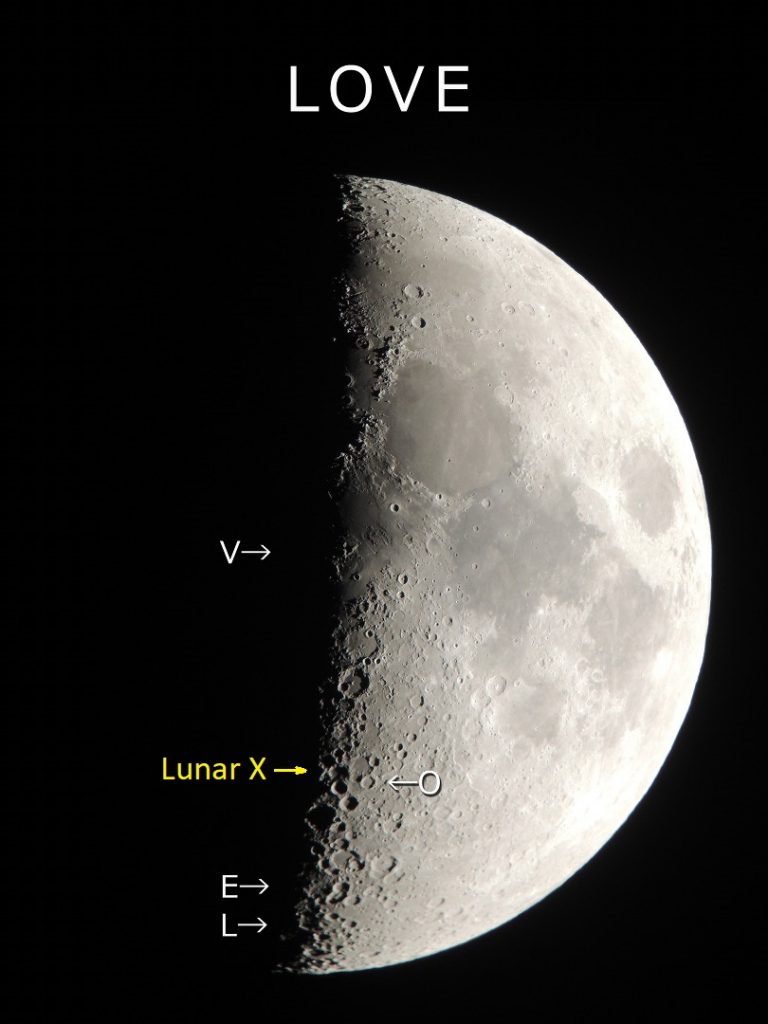

This week everyone on Earth will see the waxing moon in evening – the best circumstances for looking at the moon in binoculars and backyard telescopes. Since it will be rising in daytime, you can check it out in a blue sky long before junior astronomers have to head to bed – but ensure that no one aims optics anywhere near the sun. Under magnification, the lunar terrain along the curved, pole-to-pole terminator boundary line will be cast into stark relief by the nearly horizontal rays of sunlight illuminating it. New features are showcased each night! The only downside is that July evening moons don’t climb very high in the sky for mid-northern latitude observers – so their views will be contaminated by atmospheric turbulence and smoke or dust in the air. (It’ll be nice and high for Southern Hemisphere observers, though.)

Tonight (Sunday) the crescent moon will shine a short distance below the bright star Porrima in Virgo (the Maiden). In a backyard telescope, Porrima splits into a neat little pair. On Monday night, the nearly half-full moon will shine just to the right (celestial northwest) of Virgo’s brightest star Spica. The moon will complete the first quarter of its orbit around Earth, while still in Virgo, on Tuesday at 6:07 pm EDT or 3:07 pm PDT or 22:07 Greenwich Mean Time. The 90-degree angle formed by the Earth, sun, and moon at that time will cause us to see our natural satellite half-illuminated – on its eastern side. The terminator line will temporarily straighten.

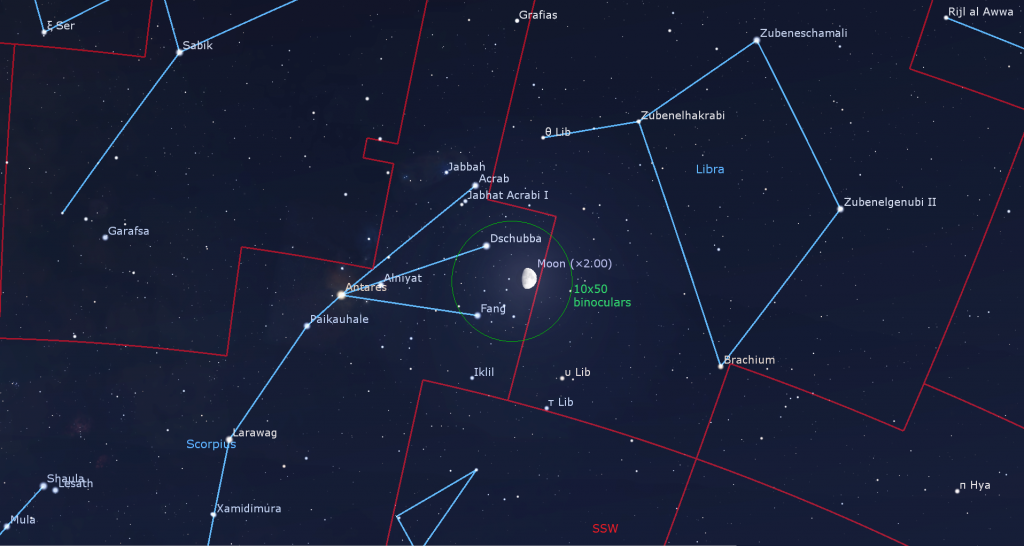

The slightly gibbous moon will spend Wednesday night among the stars of Libra (the Scales). The medium-bright star Zubenelgenubi will sparkle to the moon’s upper right (or celestial north). That nice double star is easily split in binoculars as well as a backyard telescope. Two prominent stars named Zubeneschamali and Brachium are located a fist’s width above and below Zubenelgenubi, respectively. Brachium is a reddish star. Zubenelgenubi and Zubeneschamali (the brightest star in Libra) used to mark the scorpion’s claw tips until those star were “stolen” to make up Libra. Their names mean northern and southern claw.

Speaking of the scorpion, after dusk on Thursday, the waxing gibbous moon will shine in western Scorpius just to the right of the up-down row of small white stars that form the scorpion’s claws nowadays. From top to bottom, the stars are named Jabbah or Nu Scorpii, Graffias or Acrab, Dschubba, Fang or Pi Scorpii, and Iklil or Rho Scorpii. Graffias, Dschubba, and Fang are the brightest. A backyard telescope at high magnification will reveal that Nu Scorpii, Graffias, and Dschubba are close-together double stars. On Friday the moon will hop east to shine a few finger widths to the left of Scorpius’ brightest star, the red giant Antares. Antares is located just 4 degrees south of the ecliptic. That means that the moon, and even the occasional planet, can pass in front of (or occult) it. Antares’ name arises from an ancient Greek expression for “rival to Ares”, which we know better as the planet Mars.

On the coming weekend the bright, nearly full moon will shine among the Teapot-shaped stars of Sagittarius (the Archer). The bright moon will obscure the rich Milky Way that fills the southern sky.

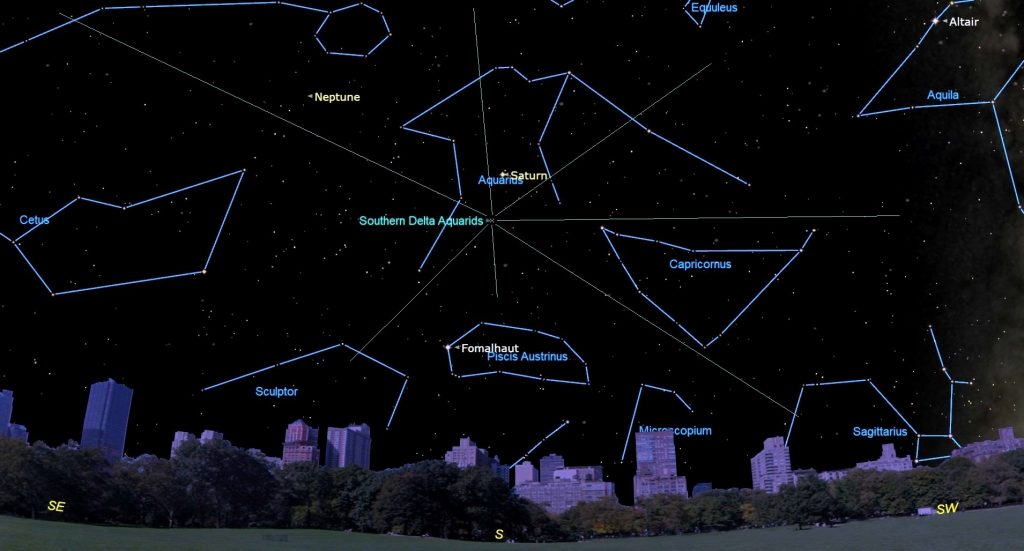

Southern Delta Aquariids Meteor Shower

The annual Southern Delta Aquariids meteor shower, which runs from July 18 to August 21, is caused when the Earth passes through a cloud of tiny particles dropped by a periodic comet – likely Comet P/2008 Y12 (SOHO). The shower will peak overnight on Saturday-Sunday, July 29-30, but is especially active for a week surrounding that date. This shower commonly generates 15-20 meteors per hour at the peak, but is best seen from the southern tropics, where the shower’s radiant, in Aquarius (the Water-Bearer), is positioned higher in the sky. Since there will be lots of moonlight around the peak, watch for fewer meteors early this week, when the sky will be darker. The prolific Perseids meteor shower, which runs annually between July 17 and August 26, has begun, too! That shower will peak on August 12-13.

Meteor showers are events that re-occur on the same dates every year when the Earth’s orbit carries us through zones of small particles left behind by multiple passes of periodic comets. (The analogy would be the material tossed out of a dump truck as it rattles along. The roadway gets pretty dirty if the truck drives the same route a number of times!) Over time, the dust-sized and sand-sized (and sometimes larger) particles accumulate and spread out into a ring-shaped cloud in interplanetary space.

When the Earth plows through the cloud, the particles are caught by our gravity and burn up as they fall through our atmosphere at speeds on the order of 200,000 km/hr. The friction caused by grains moving that quickly through the air generates intense heat that ionizes the air – producing the long glowing trails we see. The duration of a meteor shower depends on the width of the particle cloud – and therefore how long Earth takes to pass through it. The shower’s intensity depends on the type of particles in it, and on whether we pass through the densest portion, or merely skirt the edges. Not surprisingly, a shower’s performance can vary from year to year.

The nickname for meteors is “shooting stars” or “falling stars”, but they bear no physical connection to the distant stars. The action is taking place 100-200 km over your head and within Earth’s blanket of atmosphere. All of your favourite constellations will look the same as ever at the end of the shower!

While visible anywhere in the night sky, meteors will appear to be travelling away from a location in the sky called the radiant. The Southern Delta Aquariids meteor shower radiant is located in Aquarius (the Water-Bearer) – hence the name. This year, the bright planet Saturn will be shining a slim palm’s width above (celestial north) of the radiant – making it a nice signpost. The Southern Delta Aquariids radiant will rise above the southeastern horizon in late evening – and climb a third of the way up the southern sky around 3 am local time. Meteor showers are busiest in the hours before dawn because that’s the time when the sky overhead is plowing directly into the oncoming debris field, like bugs splatting on a moving car’s windshield. When the radiant constellation is highest, more of the sky is available for meteors. When it’s low, half of the meteors are hidden below the horizon.

To see the most meteors during any shower, try to find a safe, ideally rural, viewing location with as much open sky as possible. If you can hide bright lights behind a building or tree, that will help. You can start watching as soon as the sky becomes dark. That’s also a good time to catch the rarer, very long meteors produced by particles skipping across the Earth’s upper atmosphere. Don’t worry about watching the radiant. Meteors in that part of the sky will be heading directly towards you and will have very short trails. Instead, try to track the meteors’ paths backwards to find their radiant.

Bring a blanket for warmth and a chaise to avoid neck strain, plus snacks and drinks. Try to keep watching the sky even while chatting with friends or family – they’ll understand. Call out when you see one; a bit of friendly competition is fun!

Try not to look at your phone or tablet – its bright screen will spoil your dark adaptation. If you must use it, turn the brightness down, or cover the screen with red film. Disabling app notifications will reduce the chances of unexpected bright light, too. And remember that the narrow fields of view that binoculars and telescopes deliver will not help you see meteors. Good luck!

The Planets

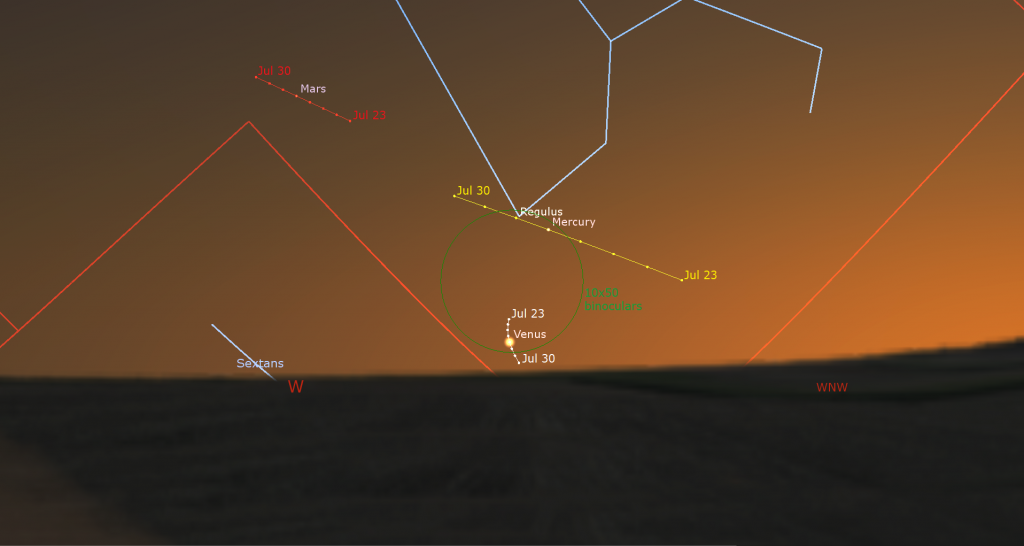

Three planetary neighbours of Earth are all gathered above the western horizon after sunset as this week begins – but only observers located south of about 30° N latitude, including the tropics and the Southern Hemisphere, will be able to see them easily.

Venus, the brightest of the trio, will emerge from the post-sunset twilight sky first. At the latitude of Toronto, you’ll need to stand in a spot with a low, unobstructed horizon to find it. Good binoculars might hint at the fact that Venus is now a slim crescent, and a backyard telescope should show a rather blurry, dancing image of the planet. Tonight (Sunday) at the latitude of Toronto, Venus will set around 8:30 pm local time. By about mid-week, we’ll lose sight of our sister planet altogether, ending its seven months-long stint as the “Evening Star”. After passing well south of the sun in mid-August, Venus will return to grace the eastern pre-dawn sky a few weeks later.

While Mercury is not “next door” to Earth as orbits go, it is, on average, the closest planet to us. Mercury will be swinging a little farther from the sun each night, allowing it to linger after Venus and Mars depart in the coming days. Mercury will be brightening a little more each night, too. Once the sun has set, look for Mercury’s dot positioned less than a palm’s width above the west-northwestern horizon, and to the upper right of Venus. Mercury’s current evening apparition will be the best one of the year for Southern Hemisphere observers, but its position just north of the very tilted evening ecliptic will keep the planet very low in the sky after sunset for mid-northerners – making this a lengthy, but poor quality showing for us.

In a telescope, Mercury will show a waning gibbous phase. On Friday, Mercury will be located just 7 arc-minutes (or about one-quarter of the moon’s diameter) to the lower left of Leo, the Lion’s brightest star, Regulus. Skywatchers at southerly latitudes will see their conjunction more easily. On the surrounding nights, Mercury will be farther from Regulus, but still telescope-close to it. On Thursday-Friday Venus will move to within a palm’s width below Mercury and Regulus.

Mars is in the western sky, too – bit it’s large distance from Earth has reduced its brightness to far below Venus and Mercury. You can try using binoculars to see its faint, reddish speck to the upper left (or celestial east) of Venus and Mercury. Mars and Mercury will cozy up a little in two weeks. Mars’ easterly motion along the ecliptic will delay its conjunction with the sun for a while yet.

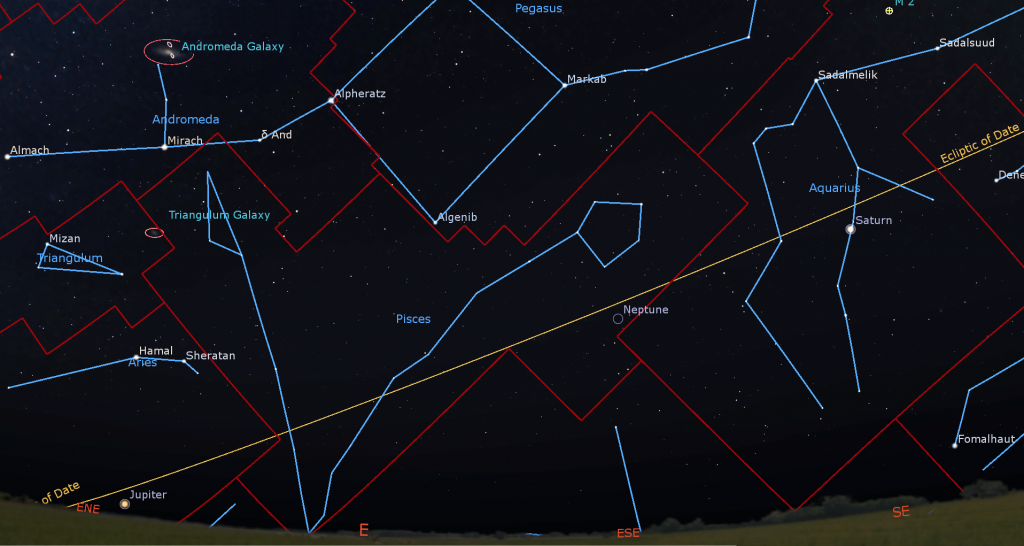

This week, the creamy-yellow dot of Saturn will rise in the east-southeast at about 10:15 pm. It’ll climb high enough to clear the rooftops about an hour later – but the best time to view Saturn in a telescope will be before dawn, when it will be located a third of the way up the southern sky. If you head outside by 5 am, you’ll be able to see the low-brightness stars of Aquarius (the Water-Bearer) shining around Saturn, and the bright trio of the Summer Triangle stars shining well off to the upper right. The very bright star Fomalhaut (or Alpha Piscis Austrini, the Southern Fish) will shine two fist diameters below Saturn during this year.

Saturn and its beautiful rings are visible in any size of telescope. If your telescope is good quality and the air is steady, try to see the Cassini Division, a narrow gap curving between the outer and inner rings, and a faint belt of dark clouds that encircle the planet. Remember to take long, lingering looks through the eyepiece – so that you can catch moments of perfect atmospheric clarity.

From here on Earth, Saturn’s axial tilt of 26.7° lets us see the top of its ring plane, and allows its brighter moons to array themselves above, below, and alongside the planet. Saturn’s largest and brightest moon Titan never wanders more than five times the width of Saturn’s rings from the planet. The much fainter moon named Iapetus can stray up to twelve times the ring width during its 80-day orbit of Saturn. The next brightest moons Rhea, Dione, Tethys, Enceladus, and Mimas all stay within one ring-width of Saturn.

During this week, Titan will migrate counter-clockwise around Saturn, moving from the left (celestial east) of Saturn on Monday morning to close in at Saturn’s lower left (celestial southeast) next Sunday morning. (Remember that your telescope will probably flip the view around.) How many of the moons can you see in your telescope? You may be surprised at how many moons you can see if you look closely. Saturn will be available for our evening viewing pleasure through its opposition in late August and then on until mid-winter! This summer the blue planet Neptune, 600 times fainter than Saturn, will be lurking two fist diameters to Saturn’s left, or 21° to its celestial northeast.

Bright, white Jupiter, which shines about 16 times brighter than Saturn, will rise at about 12:45 am local time this week. Hamal and Sheratan, the brightest stars of Aries (the Ram), will shine a generous fist’s diameter above the giant planet this year. Jupiter will be easy to see until almost sunrise, when it will shine halfway up the southeastern sky. Jupiter will be rising in late evening from the second week of August onward, and will pose for after dinner star party views until March, 2024.

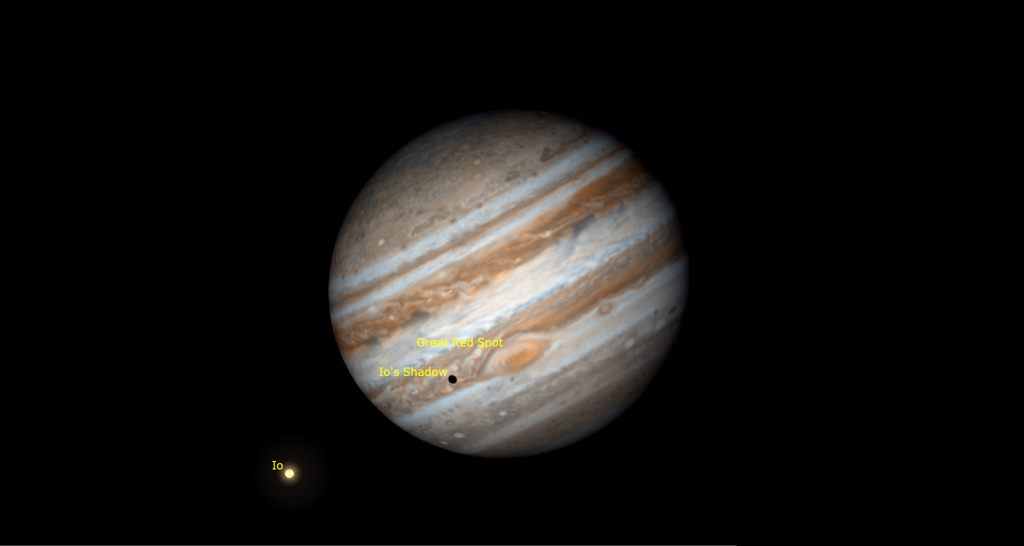

Binoculars will show Jupiter’s four Galilean moons lined up beside the planet. Named Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto, in order of their orbital distance from Jupiter, those moons complete orbits of the planet every 1.7, 3.6, 7.2, and 16.7 days, respectively. If you see fewer than four moons, then one or more of them is crossing in front of or behind Jupiter, or hiding in Jupiter’s dark shadow – or two of the moons are very close together or occulting one another. All four of them will huddle to the west of Jupiter next Saturday morning – but Europa will be hidden within Jupiter’s shadow for some of the time. From time to time, the small, round, black shadows cast by Jupiter’s Galilean moons become visible in amateur telescopes when they cross (or transit) the planet’s disk. On Wednesday morning, July 26, Ganymede’s large shadow will cross Jupiter near its south pole from 1:45 am to 3:40 am EDT (or 05:45 to 07:40 GMT). On Thursday morning, July 27, Io’s small shadow will follow the Great Red spot across Jupiter’s equatorial region from 2:55 to 5 am EDT (or 06:55 to 09:00 GMT).

Even a small, but decent quality telescope can show you Jupiter’s dark belts and light zones, which are aligned parallel to its equator. With a better grade of optics, Jupiter’s Great Red Spot, a cyclonic storm that has raged for hundreds of years, becomes visible for several hours when it crosses the planet every 2nd or 3rd night. For observers in the Americas, that GRS will cross Jupiter’s disk on Monday, Thursday, and Saturday morning. If you have any coloured filters or nebula filters for your telescope, try enhancing the spot with them.

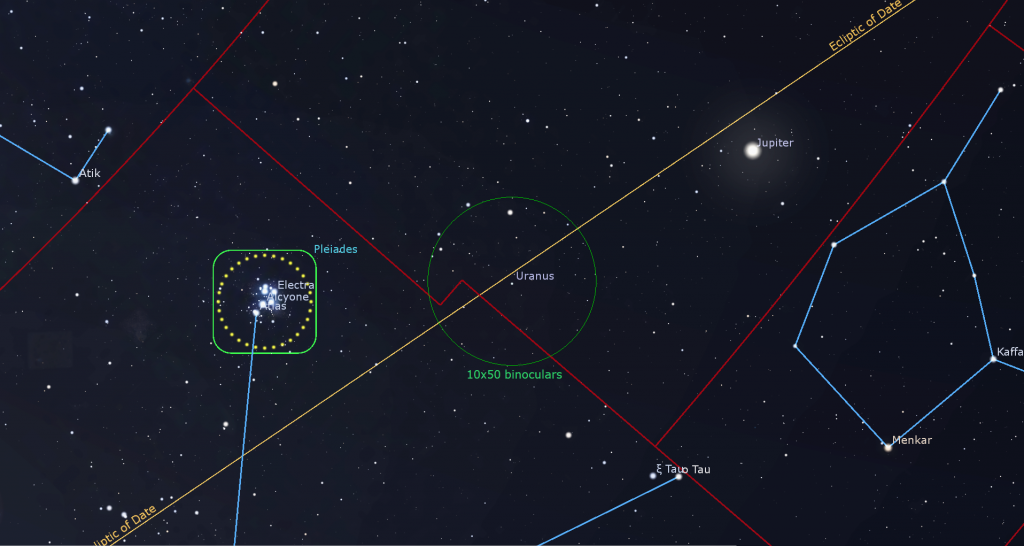

The blue-green ice giant planet Uranus is following Jupiter across the sky this year. Uranus is located a fist’s diameter to the bright planet’s lower left (or celestial east) this summer. The bright little Pleiades Star Cluster will be located almost as far to Uranus’ left. The magnitude 5.8 planet is visible in binoculars and small telescopes if you know where to look. It will become much easier to see in the coming weeks when it climbs higher.

Public Astronomy-Themed Events

Every Monday evening, York University’s Allan I. Carswell Observatory runs an online star party – broadcasting views from four telescopes/cameras, answering viewer questions, and taking requests! Details are here. They host in-person viewing on the first clear Wednesday night each month. Other Wednesdays they stream views online via the observatory YouTube channel. Details are here.

Taking advantage of the crescent moon in the sky this week, the RASC Toronto Centre astronomers will hold their monthly City Sky Star Party in Bayview Village Park (a short walk from the Bayview TTC subway station), starting after dusk on the first clear weeknight this week (Mon to Thu only). Check here for details, and check the banner on their website home page or Facebook page for the GO or NO-GO decision around 5 pm each day.

On the first clear weeknight this week (July 24-28) the public are invited to Binoculars Stargazing on the lawn at the David Dunlap Observatory. Arrive for this free program at sunset. You’ll learn to use star charts and basic observing techniques, and then use your binoculars to follow a guided tour through the night sky by RASC Toronto Centre astronomers, and stay after the tour to practice your new skills. Please wear / bring appropriate supplies for being outside. Note that there is no building or washroom access during this program. All participants under the age of 16 must be accompanied by an adult. As this program is weather dependent, please visit RASC Toronto’s home page or Facebook page for a GO or NO-GO call.

On Tuesday evening, July 25 at 7 pm EDT at the Richmond Hill Central Public Library, join Royal Astronomical Society astronomers for an intro to astronomy, an overview of celestial objects that can be seen from suburban backyards and cottage-country, and ideal observing targets for the season. This free public presentation will take place in Room A of the Central Library at 1 Atkinson Street, Richmond Hill. Register via Eventbrite here.

On Saturday, July 29 from 9:30 to 11:30 pm EDT, the in-person DDO Astronomy Speakers Night program will feature Quinton Weyrich, the outreach coordinator for the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada at the David Dunlap Observatory. He will speak on Taking Back the Night Sky: What We Can Do About Light Pollution.After the presentation, participants will tour the observatory and see a demonstration of the 74” telescope pointed to an interesting celestial object for the visitors to view (weather permitting). More information is here and the registration link is at ActiveRH.

My free, family-friendly Insider’s Guide to the Galaxy webcast with RASC National returns on Tuesday, August 1 at 3:30 pm EST. We’ll focus on an interesting topic in astronomy. Then we’ll highlight our next batch of RASC Finest NGC objects. You can find more details and the schedule of future sessions here.

Keep looking up, and enjoy the sky when you do. I love questions and requests. Send me some!