Planets Blaze in Evening, a Comet Peaks Midweek, a Bright Mini Moon, Maximum Mercury in Morning, and Will Willie See His Shadow?

This terrific image by Gabor Balazs shows the bright planet Mars (top centre) shining between the little Pleiades CLuster (right of centre) and the V-shaped Hyades Cluster, which forms the face of Taurus, the Bull in late December, 2022. The bright reddish star Aldebaran shines at the corner of the V. The image spans about two fist diameters (20 degrees) of the sky. It was the NASA APOD image for December 30, 2022. More of Gabor’s work is posted at https://www.asztrofoto.hu/adatlap/BGabor

Hello, Mid-winter Stargazers!

Here are your Astronomy Skylights for the week of January 29th, 2023 by Chris Vaughan. Feel free to pass this along to your friends and send me your comments, questions, and suggested topics. You can also follow me on Twitter as @astrogeoguy! Unless otherwise noted, all times are expressed in Eastern Time. To subscribe to these emails please click this MailChimp link.

If you’d like me to bring my Digital Starlab portable inflatable planetarium to your school or other daytime or evening event, or deliver a session online, contact me through AstroGeo.ca, and we’ll tour the Universe, or the Earth’s interior, together! My terrific book with John A. Read entitled 110 Things to See With a Telescope is a guide to viewing the deep sky objects in the Messier List – for both beginners and seasoned astronomers. DM me to order a signed copy!

The waxing moon will brighten the sky this week, somewhat spoiling the view of Comet C/2022 E3 (ZTF) during its closest approach to Earth. Consider rising between moonset and sunrise to see it. In the meantime, consider seeing the sights on the bright moon itself! Venus and Jupiter will blaze after sunset, the moon will cozy up to Mars at night, and Mercury will peak in visibility before sunrise. Oh, and Thursday is Groundhog Day! Read on for your Skylights!

Thursday is Groundhog Day

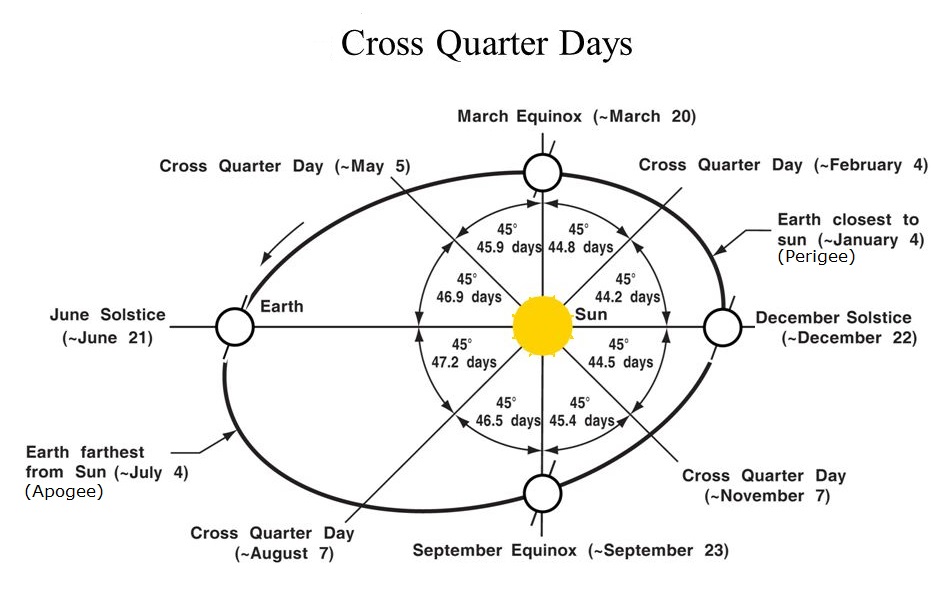

Hey! Thursday morning, February 2 is Groundhog Day! A cloudy day for Wiarton Willie and Punxsutawney Phil supposedly augurs for an early spring. But why does it fall on February 2 each year? That date aligns with one of the four so-called cross-quarter days, which are the midpoints between the solstices and equinoxes. February 2 is about midway between the winter solstice and the vernal equinox – so we can expect the weather to start being more spring-like and less winter-like afterwards – no matter what your local groundhog or other burrowing rodent sees. If an early spring means clear night skies, astronomers are all for it!

You cannot merely divide our 365.25-day year into four 91.3-day-long seasons and then count half that many days past each equinox or solstice to reach the cross-quarter points. Planets with elliptical orbits move faster when they are closer to the sun and slower when they are farther away. Since Earth is moving more slowly at aphelion in early July, summer in the Northern Hemisphere are about five days longer than winter. And winters are a couple of days shorter than 91.3. The timing of solstices and equinoxes can vary by 18 hours, so their dates aren’t always the same, either. The true mid-point of winter in 2023 will occur at 9:27 pm EST on Friday, February 3, which converts to 02:27 Greenwich Mean Time on February 4.

Groundhog Day has been observed since the 1880’s. It began as the German “Badger Day” observed on Candlemas, which is celebrated on February 2 by Roman Catholics. It marks the 40th and final day of the Christmas-Epiphany period. In contemporary paganism, the day is called Imbolc, a traditional time for initiations. Gaelics observe the traditional festival of Saint Brigid of Kildare. The other three cross-quarter days are May Day (Beltane) on May 1, and Lughnasath or Lammas on August 1, and All Hallow’s Day (Samhain) on November 1. I think you can guess which spooky “holiday” that last one connects to. Anyway – I guess those of us in wintry climes should cross our fingers and hope for cloudy skies on Thursday.

Have you noticed that the sky is brighter at dinner time nowadays? At this time of year in mid-northern latitudes, the sun sets about 2 minutes later every night and rises a minute earlier in the morning – dramatically lengthening our daylight hours with each passing week.

Hey! Thursday morning, February 2 is Groundhog Day! (See what I did there? J)

Comet Updates

Comet c/2022 E3 (ZTF) is predicted to appear brightest in the sky while it passes nearest to the Earth – at a distance of 43 million km – around midday on Wednesday, February 1. That means our absolute best times for viewing it in the Americas will be the dark sky period from moonset to the start of astronomical twilight – or about 5 to 6 am on Wednesday morning. Both Tuesday and Wednesday evening will allow us to view the comet when it’s high in the sky, but the nearly 90%-illuminated moon will spoil the view somewhat.

The comet’s orbit, which is nearly perpendicular to the plane of our solar system, has it diving down (southward) through the solar system between the orbits of Earth and Mars. Comets normally display their largest coma (fuzzy head) and tail while they are nearest the sun (or perihelion), which happened on January 12. They appear larger and brighter in the sky while they are closer to Earth. You can view and play with Comet E3’s orbit in 3D here.

The media have been calling Comet E3 a “rare green comet” and suggesting that it will be spectacular. Comets frequently look greenish when viewed in a big telescope or in a long exposure photograph. The green is produced when diatomic carbon released from the comet’s icy snowball core is ionized by solar radiation. It’s only rare in the sense that we seldom get a comet that’s visible without a telescope. In the past few days, astronomers have been reporting its brightness to be about magnitude 5.0. That’s almost at the limit of visibility for unaided human eyes in a dark sky. Thankfully, it is visible in full-size binoculars from a dark site and in backyard telescopes, where it will look like a faint grey or pale greenish fuzzy patch. Unfortunately, a bright moon will hamper our views this week. Prepare to be underwhelmed.

To find Comet E3, take your binoculars outside after it gets dark and face north. The comet is now circumpolar, meaning that it will never set below the horizon for observers at mid-northern latitudes. Since the sky revolves around the North Celestial Pole and nearby Polaris, the comet will travel in a big circle around Polaris during Earth’s 24 hour day. Tonight (Sunday) after dusk the comet will be located a fist’s diameter (10°) to the right of Polaris – on the line connecting Polaris to the bright star Dubhe in the Big Dipper’s bowl. The comet will be easiest to see when it’s highest in the sky during the wee hours of the night – but you can certainly take a look anytime of the night. Remember to account for the sky revolving around Polaris.

Comets are speedy! With each passing day the comet will glide a palm’s width (or 6.3°) higher in the evening sky, meaning that good quality views begin earlier and earlier. Its path this week will carry it toward the very bright star Capella in Auriga (the Charioteer), which sparkles nearly overhead in evening. On Wednesday, the peak night, the comet will be located in Camelopardalis (the Giraffe), almost exactly midway between Dubhe and the bright star Mirfak in Perseus (the Hero). It’ll be highest in the sky, with Polaris below it, around 9:45 pm local time. On next Sunday night, the comet will pass a thumb’s width to the right (or 1.5° to the celestial west) of Capella and will be highest at 8:30 pm.

Comets are known for their tails. Many comets sport two tails – a narrow, blueish one that is composed of glowing ionized particles spread out in a direct line away from the sun, and another broader, dusty tail that is composed of debris dropped as the comet moves through the solar system. That second tail follows the “road” the comet has travelled, so it can be curved. For Comet C/2022 E3 (ZTF), recent images have shown the long, but faint ion tail pointed toward celestial SW. The dust tail is a faint wedge on the northern side of the coma. In the evening sky, those directions will be towards the upper right and down, respectively – but a telescope will flip and/or mirror the view. Austrian astronomer Michael Jäger has been posting terrific still and animated images on Twitter as @Komet123Jager.

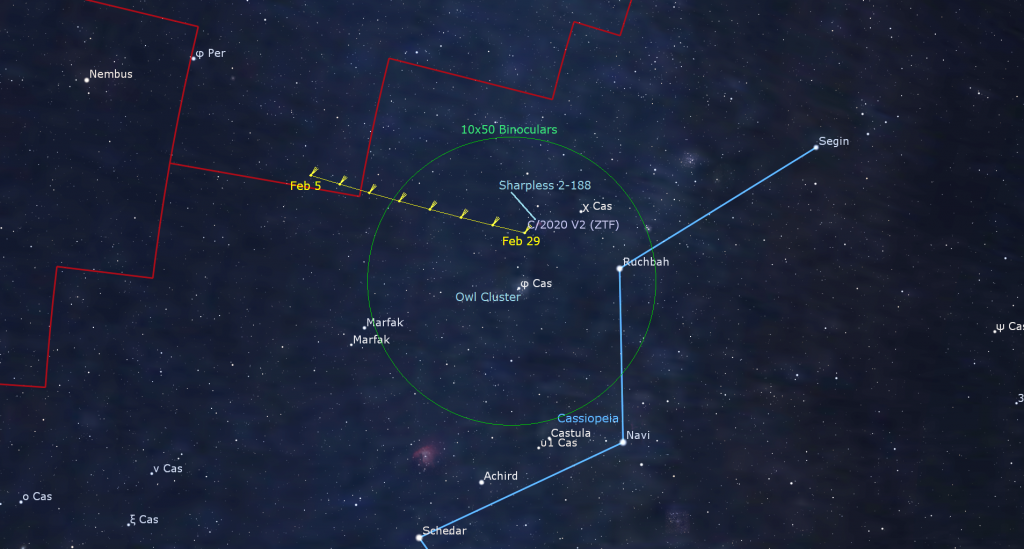

The other ZTF comet, named C/2020 V2 (ZTF), is in the northern sky, too – but on the opposite side of Polaris near the W-shaped stars of Cassiopeia (the Queen). It’s available for viewing between dusk and late evening – but you’ll need a telescope and a relatively dark location. Unfortunately, the bright moon will limit its visibility this week. Comet V2 passed closest to Earth in early January. It will remain at about the same magnitude 10 brightness over the month as it dives through the plane of the solar system between the orbits of Mars and Jupiter. Its perihelion will be later this year. You can play with a nice interactive 3D model of its orbital path here.

This week Comet V2 will be travelling celestial southward away from the star Ruchbah (or Delta Cassiopeiae), which marks the peak in the shallower half of W-shaped of Cassiopeia (the Queen). Since the northern sky rolls around the celestial pole during the night, that motion translates to towards the left during evening – in the direction away from Polaris.

This fainter comet is highest in the sky after dusk, and then it descends on the left-hand (western) side of Polaris during evening – so try to view it right after dinner. (Don’t forget to chill down your telescope, with its lens caps on, in a secure location for an hour or two ahead of viewing.) This comet is moving much more slowly. Tonight (Sunday) the comet will pass close to the faint emission nebula named Sharpless 2-188. The Dragonfly / Owl / ET Cluster (or NGC 457) will sparkle a finger’s width below the comet, too.

Both comets were discovered by the robotic widefield camera of the Zwicky Transient Facility (or ZTF) on Mount Palomar in California, one in 2020 and the other in 2022. The comets’ positions around the north celestial pole mean that only sky-watchers in the Northern Hemisphere can see them. Southern Hemisphere observers can view another comet named C/2017 K2 (Panstarrs) in binoculars. It’s climbing the southwestern evening sky.

The Moon

Everyone on Earth except Antarctica will enjoy some evening moonlight this week as our planetary partner waxes toward the February full moon. Let’s look at where the moon will be and what features you can view on it – with unaided eyes, binoculars, and backyard telescopes.

Tonight (Sunday) the moon will appear a little more than half illuminated while it shines several finger widths below the bright little Pleiades Cluster in Taurus (the Bull). You might need your binoculars to see the cluster’s stars against the bright sky. The moon will take until Wednesday afternoon to complete its passage through the big bull. In the meantime, you might spot the pale ghostly form of the moon in the afternoon daytime sky. Polarized eyeglasses will boost the contrast. Just tip your head left or right until the sky darkens the most. That works when using binoculars or a telescope, too.

On Monday night, the waxing gibbous moon will shine close enough to the bright reddish dot of Mars for them to share the view in a backyard telescope. After dusk in the Americas, look high in the southern sky to see the moon positioned a short distance to Mars’ right (or celestial southwest). Through the night, the moon’s eastward orbital motion will carry it closely past the red planet while the diurnal rotation of the sky alters the angle between them. Observers located in the southern USA, Mexico, Central America and northern South America can see the moon cross in front of (or occult) Mars around 1 am Eastern Time or 06:00 Greenwich Mean Time on Tuesday, January 31. Use an app like Stellarium to determine the exact start and end times where you live.

The moon’s visit with Mars will also kick off the moon’s monthly trip through the Winter Football! Also known as the Winter Hexagon and Winter Circle, it is an asterism composed of the brightest stars in the constellations of Canis Major, Orion, Taurus, Auriga, Gemini, and Canis Minor – specifically Sirius, Rigel, Aldebaran, Capella, Castor & Pollux, and Procyon. This year, the red planet Mars’ position in Taurus between Aldebaran and Capella has turned it into the Winter Heptagon! The waxing gibbous moon will cross the giant shape from Monday to Thursday.

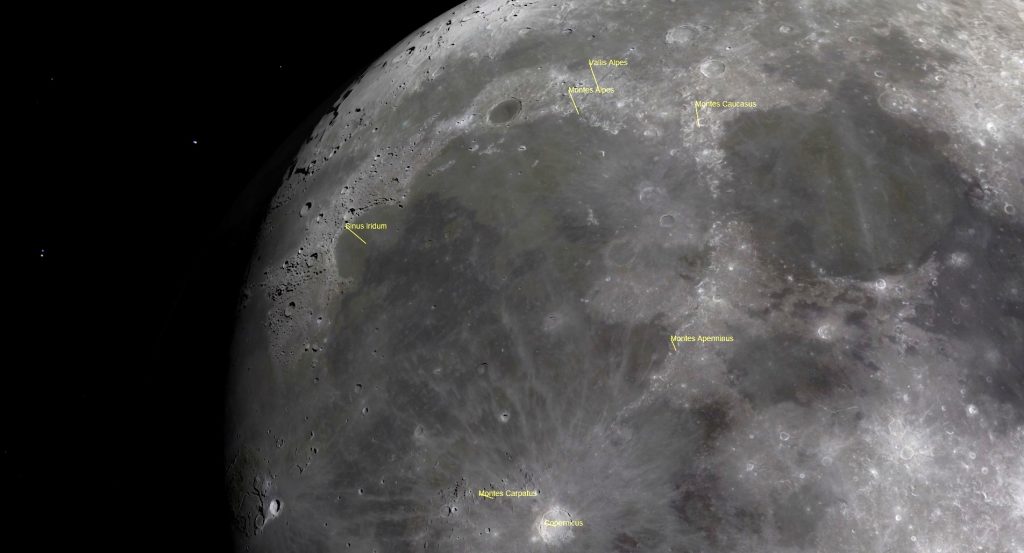

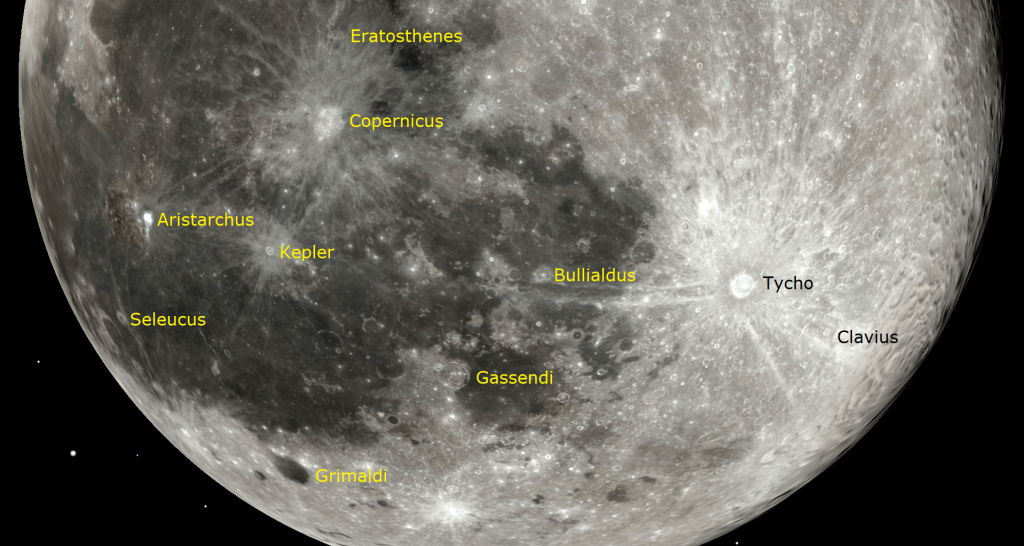

As the moon waxes fuller, the pole-to-pole terminator line slides to the left (lunar west), bringing new sections of the moon into sunlight. Sunday to Tuesday will be an excellent time to view the three impressive, curved mountain chains that encircle the eastern rim of dark Mare Imbrium. That giant impact basin, covering much of the north-central portion of the moon’s Earth-facing hemisphere, will be partly in light and partly in shadow. Those mountains, actually segments of the old crater rim, will be starkly illuminated by slanted sunlight. I’ll post a moon map showing them here.

The most northerly arc of mountains is the Lunar Alps, or Montes Alpes. Their peaks reach up to 2,400 metres above the moon’s average surface. Use binoculars or a telescope to look for a gash cutting through them called the Alpine Valley, or Vallis Alpes. It’s a rift valley, up to 10 km wide, where the moon’s crust has dropped due to faulting. To the lower right (lunar southeast) of the Alps are the Caucasus Mountains, or Montes Caucasus. This stubby, but high (up to 6,000 metres tall) mountain range disappears under a lava-flooded zone connecting Mare Imbrium with Mare Serenitatis. The mountains resume along the southeastern edge of Mare Imbrium as the lengthy Apennine Mountains, or Montes Apenninus. They, too, peter out near the prominent crater Eratosthenes, and the larger crater Copernicus beyond it. The Apennines have several large peaks reaching 5,000 metres high. On Monday, all three mountain ranges will be lit by sunlight.

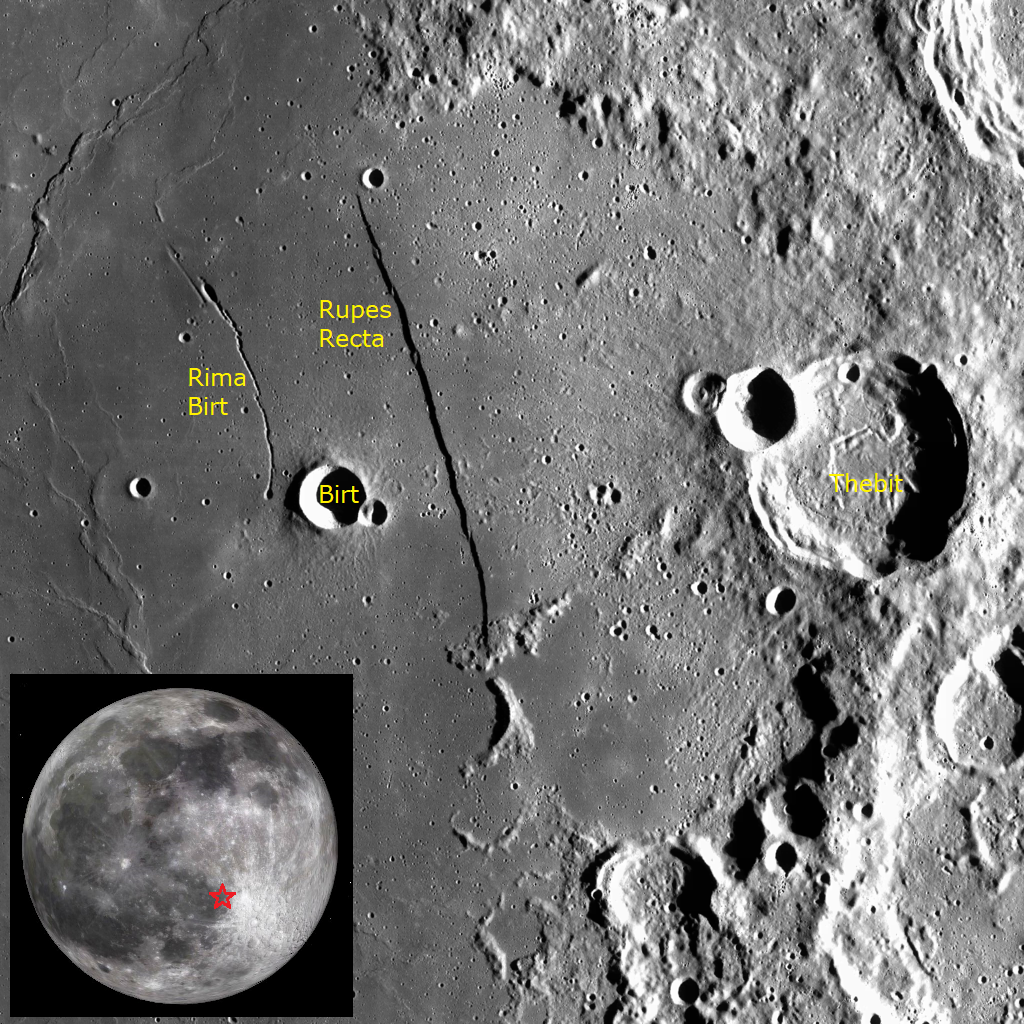

Also on Monday, the terminator will fall just to the left (or lunar west) of Rupes Recta, also known as the Lunar Straight Wall. The rupes, Latin for “cliff”, is a north-south aligned fault scarp that extends for 110 km across the southeastern part of Mare Nubium, the Sea of Clouds. That’s the dark patch sitting in the lower third of the moon’s Earth-facing hemisphere. The wall, which is very easy to see in good binoculars and backyard telescopes, is located above the very bright crater Tycho.

On Wednesday, the terminator will fall just west of Sinus Iridum “the Bay of Rainbows”. That semi-circular, 249 km diameter feature is a large impact crater that was later flooded by the same basalts that filled the much larger Mare Imbrium to its east – forming a rounded “handle” on the western edge of the mare. The “Golden Handle” effect is produced when low-angled sunlight strikes the prominent Montes Jura mountain range surrounding Sinus Iridum on the north and west – the former crater rim. Sinus Iridum is almost craterless, but hosts a set of northeast-oriented wrinkle ridges that are revealed at this phase.

The moon will spend Wednesday to Friday in Gemini (the Twins). In the eastern sky on Friday, the bright, nearly moon will shine several finger widths below (or 3 degrees to the celestial southeast) of Gemini’s bright star Pollux. The other, slightly fainter twin, the star Castor, will sparkle above them, forming a nearly straight line. As the trio crosses the sky during the night, the eastward orbital motion of the moon will carry it farther from Pollux, while the diurnal rotation of the sky rotates Gemini’s stars to the moon’s right. On Saturday the nearly full moon’s dazzling disk will overwhelm the faint stars of Cancer (the Crab) that surround it. The moon will end this week face to face with Leo (the Lion).

The full moon will occur on Sunday, February 5 at 1:28 pm EST, 10:28 am PST, or 18:28 GMT. February full moons culminate very high in the night sky and cast shadows similar to the summer midday sun. Because this moon will be full only 33 hours after the moon’s apogee, its greatest distance from Earth this month, it will look about 5% smaller than average – making it the opposite of a supermoon and the smallest full moon of 2023.

The moon has always shone down upon humans on Earth. At some point, people began to seek to understand our natural environment and to take advantage of the annual variations in the seasons to schedule planting, harvesting, hunting, and celebrating life events. The twelve (sometimes thirteen) full moons per year acted as obvious celestial markers. The full moon’s bright light allowed people to be out and about safely at night. It lit the way of the hunter or traveler before modern conveniences like electric lights, and workers in the fields devoting extra hours to get the harvest in. By the way – those extra, thirteenth full moons, which fall into different months each year, are commonly referred to as blue moons. The next one will happen in August, 2023.

Each society around the world developed its own set of stories for the moon, and every month’s full moon now has one or more nick-names related to human spirit or the natural environment. The indigenous Anishnaabe (Ojibwe and Chippewa) people of the Great Lakes region call the February full moon Namebini-giizis “Sucker Fish Moon” or Mikwa-giizis, the “Bear Moon”. For them it signifies a time to discover how to see beyond reality and to communicate through energy rather than sound. The Algonquin call it Wapicuummilcum, the “ice in river is gone” moon. The Cree of North America call it Kisipisim, the “the Great Moon”, a time when the animals remain hidden away and traps are empty. For Europeans, it is known as the Snow Moon or Hunger Moon.

Looking at the moon through binoculars and telescopes this week will show you the huge difference in the way sunlight illuminates the moon. Every month around first quarter (this weekend), the sun’s rays strike the moon from the side. In the zone alongside the pole-to-pole terminator line that separates the lit and dark hemispheres, the sun is just rising over the moon’s eastern horizon. With no atmosphere to scatter light, the shadows cast by every crater rim, mountain, and ridge are a deep black – and even very small bumps and ridges are highlighted, revealing otherwise hidden features on crater floors.

On the coming weekend, when the moon will be fully illuminated, the sunlight striking the moon will be coming from directly “behind you”, especially when you face the full moon. It’s analogous to the way the projector in the rear of a cinema lights up the movie screen in front of you. That sunlight is arriving straight-on to the moon’s surface, so it doesn’t generate any shadows. Every variation in brightness and colour you see on a full moon is due entirely to the moon’s geology, not its topography! At that time, you can easily distinguish the dark, grey, basalt rocks from the bright, white, aluminum-rich anorthosite rocks.

The basalts overlay the various lunar maria, Latin for “seas” – coined because people used to think they were water-filled. The maria are basins excavated by major impactors early in the moon’s geologic history and later flooded with molten rock that upwelled from the interior of the moon late in the moon’s geological history. That filling happened in stages. A backyard telescope will easily reveal terraces of lava that “froze” after each incursion – but those are best seen when the moon isn’t full.

The much older and brighter parts of the moon are composed of anorthosite rock. Those areas are higher in elevation and are also heavily cratered – because there has been no wind and water, or plate tectonics, to erase the scars of countless impacts. By the way, the bright, white appearance of anorthosite is produced by sunlight reflecting off of the crystals the rock is made of – the same sort of crystals you see in the granite countertops in Earth’s kitchens. And yes, there are coloured rocks on the moon.

Some of the violent impacts that created the craters in the highland regions also threw bright streams of ejected material long distances on top of the darker maria. We call those streaks lunar rays systems. Some rays are thousands of km in length – like the ones from the very bright 100 million-year-old crater Tycho in the moon’s southern central region.

Use your binoculars to scan around the moon. There are large and small ray systems everywhere! There are also places where craters recently blasted into the maria have tossed dark rays onto white rocks. And, since the dark basalt overlays the white, older rock underneath it, a small telescope will show lots of craters where a hole has been punched through the dark rock, producing a white-bottomed crater!

Several of the maria link together to form a curving chain across the northern half of the moon’s near-side. Mare Tranquillitatis the “Sea of Serenity”, where humankind first walked upon the moon, is the large, round mare in the centre of the chain. Sharp-eyes might detect that this mare is darker and bluer than the others, due to enrichment of the basalt by the metal titanium. That’s one of the reasons why Apollo 11 was sent there.

Now that you know more of the lunar terminology, here are some additional things to watch for…

The latter half of this week will also be ideal for viewing the prominent crater Copernicus in eastern Oceanus Procellarum, the “Ocean of Storms”, which is the large dark region located south of large Mare Imbrium. Copernicus is located slightly to the upper left (lunar northwest) of the moon’s centre. The Jesuit priest Giovanni Battista Riccioli, who published a labelled map of the moon in 1651, deliberately placed the craters named for astronomers Nicolaus Copernicus and Johannes Kepler, their defender Ismaël Bullialdus, and the Greek philosophers Aristarchus, Eratosthenes, and Seleucus, into the Ocean of Storms because they all dared to suggest that Earth revolved around the sun – in contravention to the church’s teachings. Riccioli honoured his fellow Jesuits Grimaldi and Clavius with prominent craters elsewhere on the moon.

The 800 million year old crater Copernicus is visible with unaided eyes and binoculars – but telescope views will reveal many more interesting aspects of lunar geology. Several nights before and after the moon reaches its full phase, Copernicus will exhibit heavily terraced edges (due to slumping), an extensive ejecta blanket outside the crater rim, a complex central peak, and both smooth and rough terrain on the crater’s floor. Around full moon, Copernicus’ rather ragged ray system, which extends 800 km in all directions, becomes prominent. Use high magnification to look around Copernicus for small craters with bright floors and black haloes – caused by impacts through Copernicus’ white ejecta that excavated dark Oceanus Procellarum basalt and even deeper highlands anorthosite.

The prominent crater Kepler is located to the lunar west of Copernicus. Smaller, but brighter Aristarchus is positioned north of them. It is one of the most colourful regions on the moon. NASA orbiters have detected high levels of radioactive radon at Aristarchus.

The Planets

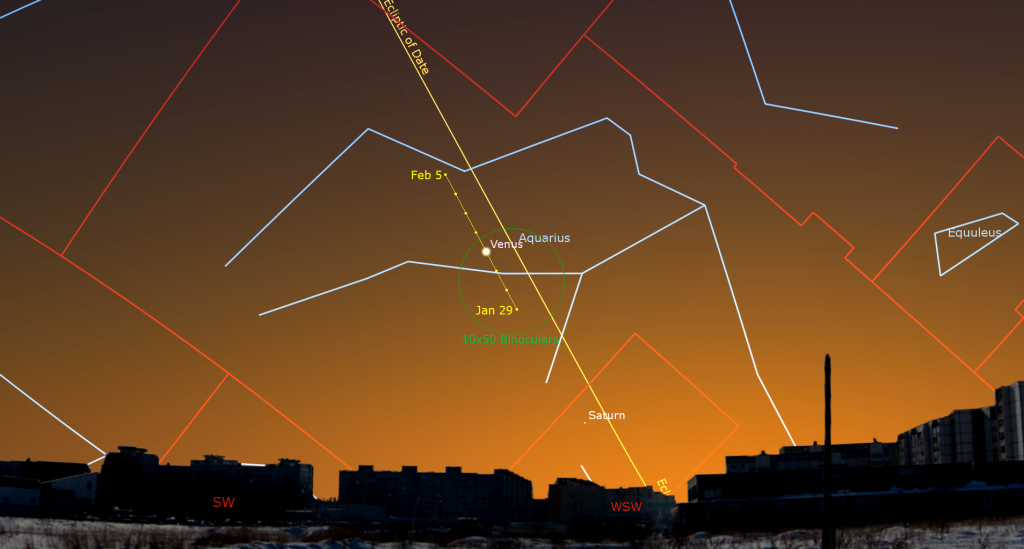

Venus has climbed far enough from the sun to gleam above the rooftops after sunset this week. The magnitude -3.86 planet will be the “Evening Star” until next July! In your telescope our cloud-shrouded sister planet will show a featureless, 91%-illuminated disk. To see its shape most clearly, look as soon as you can find it, when it will be higher and shining through less intervening air. Venus will set around 7:30 pm local time. If the bright dot you are seeing is blinking or flashing, or shifting to the left or right, it’s an aircraft. Keep searching!

Last week Venus passed 75 times fainter Saturn in a spectacular close planetary conjunction. Now Venus will climb higher while Saturn and the surrounding stars are carried lower and sunward by Earth’s orbital motion. The same effect causes the constellations to be replaced each season. You’ll find Saturn’s dot about a fist’s diameter below Venus, and a little to the right. Saturn’s descent means our time for clear views of it in a telescope are done for this year. It will pass the sun in solar conjunction on February 16, and then return to shine in the eastern pre-dawn sky starting around early April. It’ll return to the evening sky from July onward.

As Venus sinks below the treetops and the sky begins to darken well, bright Jupiter will pop into view in the lower third of the southwestern sky. Your binoculars should be able to show magnitude -2.2 Jupiter as a small disk bracketed by its line of four Galilean moons named Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto. Those moons complete orbits of the planet every 1.7, 3.6, 7.2, and 16.7 days, respectively. If you see fewer than four moons, then one or more of them is crossing in front of or behind Jupiter, or hiding in Jupiter’s dark shadow – or two of the moons are very close together or occulting one another. The moons’ arrangement varies each night. All four of them will swing to the same side of the planet on Wednesday night.

Jupiter will look best in a telescope as soon as you can spot it – while it is still reasonably high. It will sink lower through the evening and set in the west around 10 pm local time. Even a small, but decent quality telescope can show you Jupiter’s dark belts and light zones, which are aligned parallel to its equator. With a better grade of optics, Jupiter’s Great Red Spot, a cyclonic storm that has raged for hundreds of years, becomes visible for several hours when it crosses the planet every 2nd or 3rd night. For observers in the Americas, that GRS will cross Jupiter’s disk in early evening on Sunday, Tuesday, Friday, and Sunday, and during mid-evening on Tuesday, Thursday, and Saturday evening. If you have any coloured filters or nebula filters for your telescope, try enhancing the spot with them.

The round, black shadows of Jupiter’s Galilean moons are visible through a good backyard telescope when they cross the planet’s disk. On Wednesday evening, Io’s small shadow will cross Jupiter’s equator from 7:35 to 9:45 pm CST, but the event will be better viewed in more westerly time zones. The events are widely visible over the western hemisphere. Just adjust these quoted times into your own time zone.

The tiny, blue, magnitude 7.9 speck of Neptune will be located a generous fist’s width to the lower right (or 12° to the celestial west-southwest) of Jupiter this week. That’s a bit less than halfway to Venus. Like Jupiter, try to view Neptune while it is higher right after dusk. The large asteroid named (4) Vesta, equal in brightness to Neptune, will be positioned a slim palm’s width to the left of Neptune this week.

Since our closest approach back on November 30, the distance from Earth to Mars has increased dramatically. For that reason, the red planet has become dimmer in the sky and smaller in telescopes – but you can still use a small, but good quality telescope and a high magnification eyepiece to see some dark markings on its ruddy, 11 arc-seconds-wide disk. If you have coloured filters for your telescope, see if the blue, orange, or red one improves the view.

During early evening Mars will be positioned high in the southeastern sky above the stars of Orion (the Hunter) – and just above the very bright, reddish star Aldebaran, which marks the angry eye of Taurus (the Bull). The Pleiades star cluster will be twinkling less than a fist’s width to Mars’ upper right (celestial west). Over the next weeks, you’ll notice that Mars is shifting eastward above Aldebaran, and moving a bit farther away from the Pleiades each night. For now, Mars will climb very high in the south around 8 pm local time (its absolute best telescope viewing time), and then descend westward to set in the wee hours.

The blue-green dot of Uranus is located nearly halfway from Mars towards Jupiter. You can also search a generous fist’s width to the lower left (or 12.5° to the celestial southeast) of Hamal, the brightest star in Aries (the Ram). Closer guideposts to Uranus are several medium-bright stars, including Al Butain II (or Rho Arietis), Omicron Arietis, and Sigma Arietis, which will appear several finger widths from the planet – within the same binoculars field of view. Those faint stars mark the hooves of the Ram. Magnitude 5.7 Uranus will be ideally placed for telescope-viewing, high in the southern sky, after dusk this week. It will set around 1:30 am.

The main belt asteroid designated (2) Pallas is currently shining with a visual magnitude of 7.7, which is within reach of binoculars and backyard telescope. This week Pallas will still be situated in southwestern Canis Major (the Big Dog), a palm’s width to the upper right (or 6.5 degrees to the celestial west) of the bright, rear paw star Adhara. Over the next few weeks the asteroid will slide upwards (northwest) through the legs of the dog and closer to the bright star Sirius. Wait until the asteroid has risen higher, at around 10:15 pm, for the best views of it.

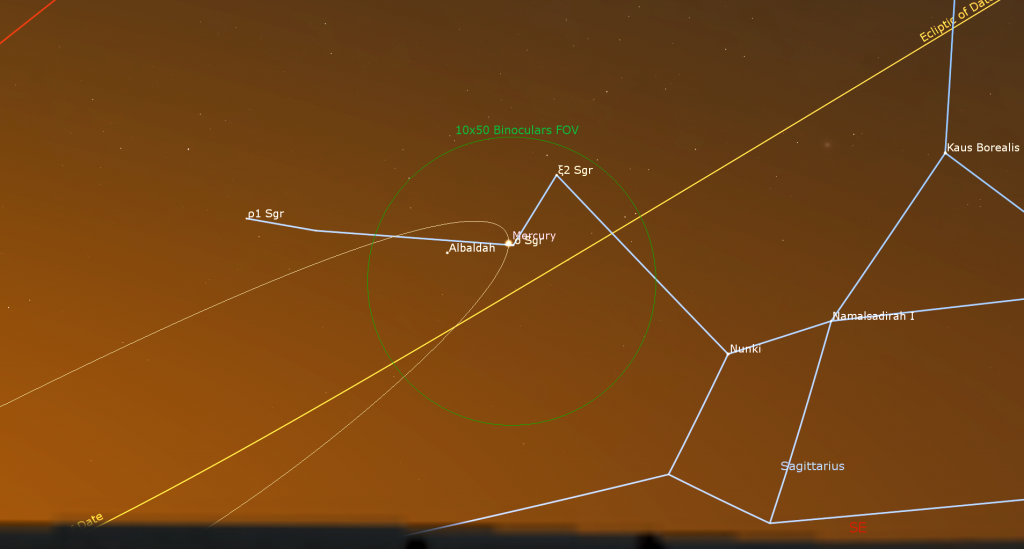

On Monday the innermost planet Mercury will reach its widest separation of 25 degrees west of the Sun, and maximum visibility for its current morning apparition. With Mercury positioned close to the tipped-over morning ecliptic in the southeastern sky, this appearance of the planet will be a relatively good one for both Northern and Southern Hemisphere observers. The optimal viewing times at mid-northern latitudes will start around 6:15 am local time. Viewed in a telescope the planet will exhibit a waxing, slightly gibbous phase. The medium-bright star Omicron Sagittarii will shine nearby.

Public Astro-Themed Events

Every Monday evening, York University’s Allan I. Carswell Observatory runs an online star party – broadcasting views from four telescopes/cameras (weather permitting), answering viewer questions, and taking requests! Details are here. They host in-person viewing on the first clear Wednesday night each month. On Wednesdays they stream views online via the observatory YouTube channel. Details are here.

My free, family-friendly Insider’s Guide to the Galaxy webcast with Samantha Jewett of RASC National returns on Tuesday, January 31 at 3:30 pm EST. We’ll focus on sights to see along the winter Milky Way and some cold weather stargazing tips. Then we’ll highlight the next batch of RASC’s Finest NGC objects. You can find more details and the schedule of future sessions here.

Keep looking up, and enjoy the sky when you do. I love questions and requests. Send me some!