The Moon’s Mostly Missing Crescent Covers Planets, See Ceres Crossing Star-Shooting Taurus, and Aquarius’ Lucky Stars!

This colour-composite image of the Helix Nebula (NGC 7293) was created from images obtained using the Wide Field Imager camera on the 2.2-metre ESO telescope at the La Silla observatory in Chile. The colours arise from a shell of gases energized by the radiation of the tiny central star. This image spans the same diameter as the full moon.

Happy Halloween, Stargazers!

Here are your Astronomy Skylights for the week of October 31st, 2021 by Chris Vaughan. Feel free to pass this along to your friends and send me your comments, questions, and suggested topics. You can also follow me on Twitter as @astrogeoguy! Unless otherwise noted, all times are expressed in Eastern Time. To subscribe to these emails please click this MailChimp link.

I can bring my Digital Starlab portable inflatable planetarium to your school or other daytime or evening event, or teach a session online. Contact me through AstroGeo.ca, and we’ll tour the Universe, or the Earth’s interior, together! My terrific new book with John A. Read entitled 110 Things to See With a Telescope is a guide to viewing the deep sky objects in the Messier List – for both beginners and seasoned astronomers. DM me to order a copy!

The moon will absent from the evening sky worldwide for nearly all of this week as it approaches the sun at new moon. Before and after new moon it will occult the planets Mercury and Venus! The darker nights will be ideal for viewing the sights in Aquarius, spooky Halloween treats, and some meteors! Meanwhile, Ceres will cross the face of Taurus. Read on for your Skylights!

Halloween Marks Mid-Autumn

Halloween, or All Hallows’ Eve, has been pinned to the date of October 31 every year. It actually originated from Samhain, a festival observed by the ancient Celts and Druids that was held to mark the end of harvest season and the beginning of winter weather. Pagan Thanksgiving, perhaps? Astronomically speaking, samhain is one of the four cross-quarter days, the season midpoints that occur halfway between each solstice and equinox.

In modern times, observers of Samhain celebrate it on November 1 – but the true mid-point of autumn will occur in the wee hours of November 7, 2021. At that time, the ecliptic longitude of the sun will be 225° – extremely close to the double star Zubenelgenubi in Libra (the Scales). The other three cross-quarter days are Groundhog Day (or Imbolc) on February 3, May Day (Beltane) on May 5, and Lughnasath or Lammas on August 7.

You can’t merely divide our 365.25-day year into four 91.3-day seasons and then count half that many days to reach the cross-quarters. Planets with elliptical orbits move faster when they are closer to the sun and slower when they are farther away. Since Earth is moving slower at aphelion in July, summers in the Northern Hemisphere are about five days longer than winters!

Southern Taurids Meteor Shower

The Southern Taurids meteor shower is active from September 28 to December 2 every year. The shower will reach a maximum rate of about 5 meteors per hour on Thursday, November 5. The long-lasting, but weak shower is the first of two consecutive meteor showers produced by debris dropped by the passage of periodic Comet 2P/Encke. The larger-than-average grain sizes of the comet’s debris often produce colourful fireballs.

Although Earth will be traversing the densest part of the comet’s debris during Thursday in the Americas, the best viewing time will occur hours later, at around 2 am local time on Friday, when the shower’s radiant, located near the Taurus-Aries boundary, will be high in the southern sky. (When radiants are lower, many of a shower’s meteors are hidden below your local horizon.) This year’s peak night will be moonless, favoring more meteors. Keep an eye out for meteors on Thursday evening, too.

While you are looking up, keep an eye out for early meteors of the Leonids shower. They’ll appear to be traveling from east to west across the sky. That shower will peak on November 17-18.

The Moon

The moon will be missing from evening skies worldwide for nearly all of this week – letting the stars twinkle a little more boldly, and allowing subtle objects like the Andromeda Galaxy and the Pleiades stars cluster to stand out. I’ll tour you through a November constellation below.

The moon won’t be visible on Halloween tonight. Last year its full orb lit the way for trick-or-treaters! Instead, the waning crescent moon will rise tonight at about 4 am local time. Early risers on Monday morning can see it shining in the eastern sky among the stars of western Virgo (the Maiden).

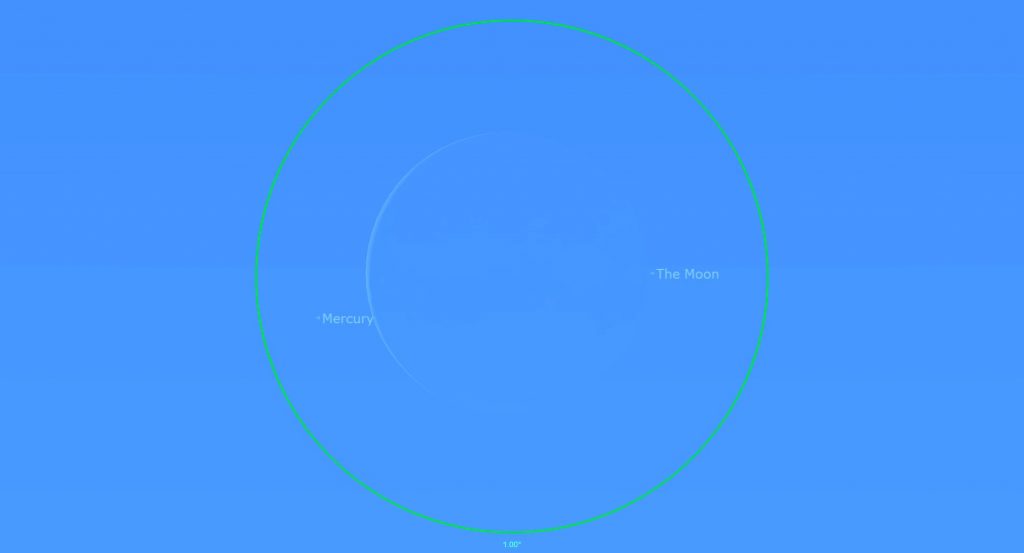

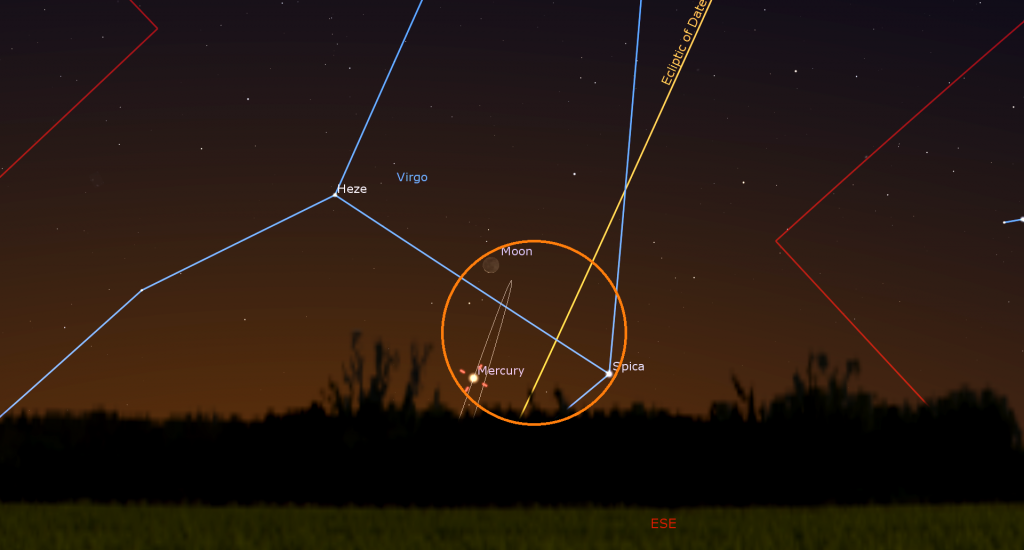

The moon will spend Tuesday and Wednesday travelling through Virgo. Look very low in the east-southeastern sky before sunrise on Wednesday to see the old crescent moon will shining prettily several finger widths above (or 4 degrees to the celestial northwest of) Mercury’s bright dot. Virgo’s brightest star Spica will be positioned a few finger widths to their right. The three objects will share the field of view in binoculars, but be sure to turn your optics away from the eastern horizon before the sun appears. Observers near the latitude of the Great Lakes should aim to be outside at about 7 am – but check the morning weather forecast before making the effort. You’ll need an unobstructed view towards the east-southeast and a cloud-free horizon.

During the daytime on Wednesday, November 3, the moon’s orbital motion will draw it closer to Mercury, culminating in a daytime lunar occultation of the planet observable in amateur telescopes from the eastern USA and Canada, and the Caribbean. Good binoculars might work, too. For Toronto, the lit crescent of the moon will cover Mercury at 3:35 pm EDT (or 19:35 Greenwich Mean Time). The planet will pop into view from behind the moon’s opposite, dark limb at 4:33 pm EDT (or 20:33 GMT). Those times will vary by location, so begin to watch several minutes early, or use an astronomy app to determine the timing where you live. An experienced observer and/or a GoTo telescope will help you find the pale moon in daytime. (Caution: Never point unfiltered optics anywhere near the sun.)

The moon will reach its new phase on Thursday at 5:14 pm EDT or 21:14 GMT. While new, the moon is travelling between Earth and the sun. Since sunlight can only reach the far side of the moon, and the moon is in the same region of the sky as the sun, the moon becomes unobservable from anywhere on Earth for about a day (except during a solar eclipse). This new phase will occur one day before the moon’s closest approach to Earth, or perigee, resulting in larger tides worldwide.

Lucky skywatchers might catch sight of the freshly minted, young crescent moon sitting very low over the west-southwestern horizon immediately after sunset on Friday. It’ll be easier to see the moon on Saturday after about 6:30 pm local time – but you’ll still need an unobstructed view and cloud-free skies.

An even prettier sight will arrive on Sunday, November 7. In the southwestern sky after sunset, the young crescent moon will shine several finger widths to the lower right (or 5 degrees to the celestial west) of the very bright planet Venus – close enough for them to share the field of view in binoculars. The duo will set at about 7 pm local time. Hours later, in midday on November 8, observers in parts of northeastern Asia and the western Aleutian Islands can see the moon pass in front of, or occult, Venus – while surrounding regions will see the moon pass very close to the planet.

The Planets

During the coming week, speedy Mercury will finish up a splendid pre-dawn appearance for mid-northern latitude observers. On Monday morning its very bright dot will be visible low in the east-southeastern sky between the time it rises (at around 6:30 am local time) and about 7:30 am. Viewed in a telescope, Mercury will show a waxing gibbous (i.e., more than 80%-illuminated) disk that will shrink daily from an initial 5.8 arc-seconds diameter. (For safety, be sure to put your optics away before the sun rises.) On each subsequent morning, Mercury will descend sunward – so make your attempt sooner than later.

Mercury’s downward trajectory will also move it directly toward Mars! The red planet is commencing a year-long journey to a bright showing at opposition in December, 2022. Mercury will be positioned a few finger widths above (or 3 degrees to the celestial northwest of) Mars next Sunday morning – but Mars will be much, much fainter. Only observers living near the tropics, where the sky is darker immediately before dawn are likely to be able to see both planets. Those planets will be even closer next week.

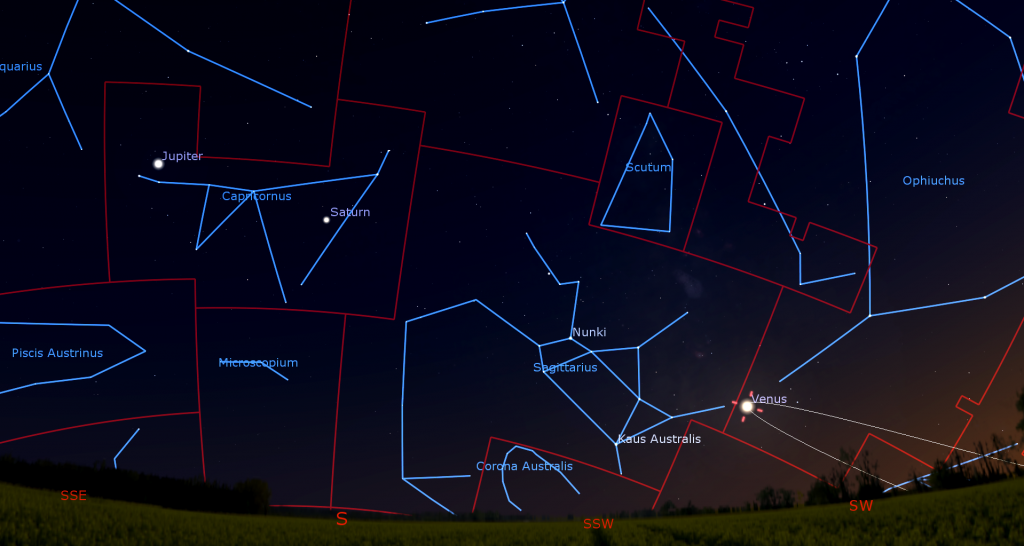

After many months in the western post-sunset sky, extremely bright Venus reached greatest elongation, 47 degrees east of the sun, last Friday. Our sister planet will continue to dominate the early evening sky for some time to come, but its position well south of a canted-over evening ecliptic will keep the magnitude -4.7 planet low in the sky for mid-northern latitude observers until later in November. This week, Venus will set in the southwest at about 8:25 pm local time. You might need to walk around to find a view of the planet between the trees or buildings.

Viewed in a telescope, Venus will appear half-illuminated, on its sun-facing side. Aim your telescope at Venus as soon as you can spot the planet in the sky (but ensure that the sun has completely disappeared first). That way, the planet will be higher and shining through less distorting atmosphere – giving you a clearer view of it. A brighter sky will also allow Venus’ shape to be seen more readily. The planet will grow in size and wane in phase every week for the rest of this year because Venus will be traveling into the space between Earth and the sun.

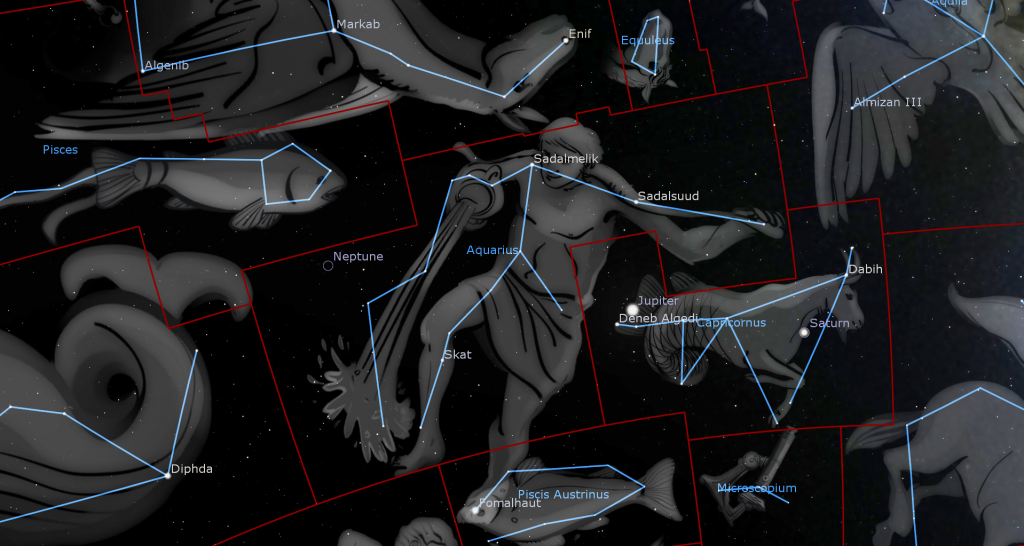

Jupiter and Saturn are now in the same quadrant of the sky as Venus. The trio of bright planets will get cosy during December, and Mercury will join them at year-end. For now, Jupiter’s bright, white dot will become visible, sitting less than a third of the way up the south-southeastern sky, a short time after dusk. 18 times fainter Saturn will join the party once the sky darkens a bit more. Binoculars will reveal Saturn’s creamy speck sitting 1.5 fist diameters to the right (or 15.5° to the celestial west) of Jupiter. At around 7:45 pm local time, they’ll reach their highest elevation in the sky, over the southern horizon. They’ll set in the west just after midnight. Jupiter and Saturn are both moving Prograde eastward at the opposite ends if the constellation of Capricornus (the Sea-Goat).

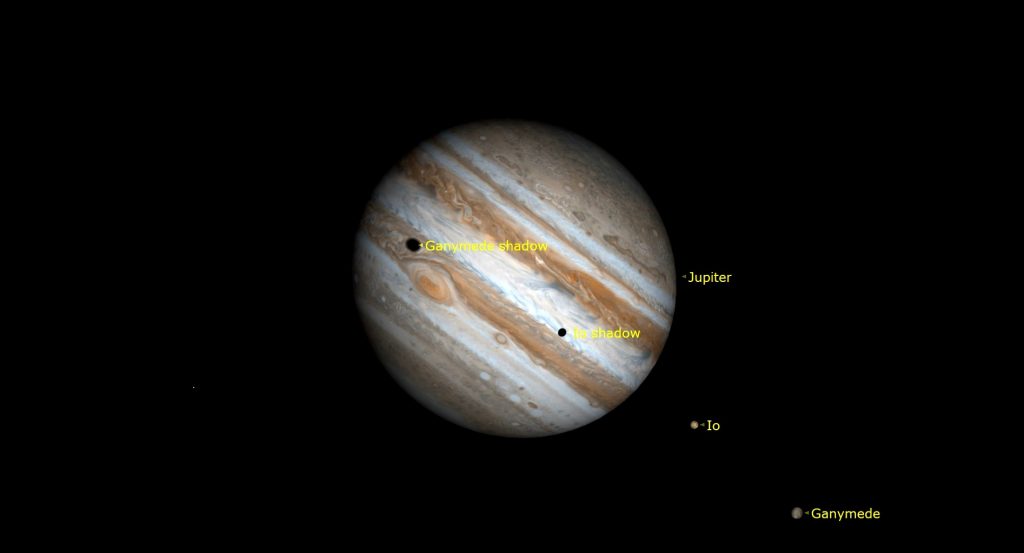

Binoculars and small telescopes will show you the Jupiter’s four large Galilean moons named Io, Europa, Callisto, and Ganymede. Since Jupiter’s axial tilt is a miniscule 3°, those moons always look like beads strung on a line that passes through the planet, and parallel to Jupiter’s dark equatorial belts. That line of moons, and the belts, tilt as Jupiter crosses the sky. The moons’ arrangement varies from night to night. Io, for example, orbits Jupiter once every 42 hours. From one night to the next night, 24 hours has elapsed on Earth – time for Io to complete half an orbit and shift from one side of Jupiter to the other. The other Galilean moons move less rapidly, taking between 3.5 and 16.7 days to orbit Jupiter.

For observers in the Eastern Time Zone with good telescopes, the Great Red Spot (or GRS) will be visible while it crosses Jupiter after dusk on Tuesday, Thursday, and Sunday; in mid-evening on Monday and Saturday, and around midnight on both Wednesday (with Io’s shadow).

From time to time, the small, round, black shadows cast by Jupiter’s Galilean moons become visible in amateur telescopes when they cross (or transit) the planet’s disk. On Tuesday evening, November 5, observers with telescopes in locations from northern Asia to Australia can watch the Great Red Spot and the small black shadows of two of Jupiter’s moons cross the planet’s disk at the same time. At 8 pm Japan Standard Time or 11:00 GMT, the Great Red Spot and Ganymede’s large shadow will join Io’s smaller shadow already in transit. The two shadows will dot Jupiter’s disk for 75 minutes, and then Io’s shadow will move off the planet. On Wednesday night, November 3 observers west of the Eastern Time Zone can see Io’s small shadow cross Jupiter from 10:35 pm to 12:45 am MDT, accompanied by the Great Red Spot! And from 7 pm until 9:15 pm EDT on Friday, Io’s shadow will cross again.

Saturn and its beautiful rings are visible in any size of telescope. If your optics are sharp and the air is steady, try to see the Cassini Division, a narrow gap between the outer and inner rings, and a faint belt of dark clouds encircling the planet. Remember to take long, lingering looks through the eyepiece – so that you can catch moments of perfect atmospheric clarity.

From here on Earth, Saturn’s axial tilt of 26.7° lets us see the top of its ring plane, and allows its brighter moons to array themselves all around the planet. Saturn’s largest and brightest moon Titan never wanders more than five times the width of Saturn’s rings from the planet. The much fainter moon named Iapetus can stray up to twelve times the ring width during its 80-day orbit of Saturn. Iapetus is dark on one hemisphere and bright on the other, so it looks dimmer when it is east of Saturn, and it looks brighter when it is west of Saturn. Iapetus reached its minimum brightness of magnitude 11.46 on Friday, October 29 and then it will double in brightness to magnitude 11.59 on December 8. It will pass very close to Saturn on November 18. The next brightest moons Rhea, Dione, Tethys, Enceladus, and Mimas all stay within one ring-width of Saturn.

During this week, Titan will migrate counter-clockwise around Saturn, moving from the right (celestial west) of Saturn tonight to the upper left (celestial northeast) of Saturn next Sunday. (Remember that your telescope will probably flip the view around.) How many of the moons can you see in your telescope?

Slow-moving Uranus will reach opposition on Friday, November 5. On that night it will be closest to Earth for this year – a distance of 2.80 billion km, or 156 light-minutes. Uranus’ minimal distance from Earth will cause it to shine at a peak brightness of magnitude 5.65 and to appear slightly larger in telescopes for a week or so centered on opposition night. At opposition, planets are above the horizon from sunset to sunrise. During autumn this year, look for the planet’s small, blue-green dot moving slowly retrograde westwards in southern Aries (the Ram), a fist’s width below (or 11.5 degrees southeast of) that constellation’s brightest stars, Hamal and Sheratan. Or use binoculars to locate Uranus using the nearby star Mu Ceti. It’s also about 1.6 fist diameters to the upper right (or 16 degrees to the celestial west-southwest) of the Pleiades star cluster. This week Uranus will be observable all night long – especially after midnight, when it will have climbed more than halfway up the southeastern sky. The moonless sky will also help you to see the planet in binoculars, telescopes, and perhaps even your unaided eyes!

Distant, dim Neptune is in the sky all night long, near the border between Aquarius (the Water-Bearer) and western Pisces (the Fishes) – and nearly three fist diameters to the left (or celestial east) of Jupiter. Moonless skies will let you see the blue, outermost planet in binoculars and backyard telescopes. The main belt asteroid named (2) Pallas is not far away. This week, Pallas will be traveling slowly downward (or southward) through Aquarius, about two finger widths to the right (celestial west of) the medium-bright star Hydor.

See Ceres

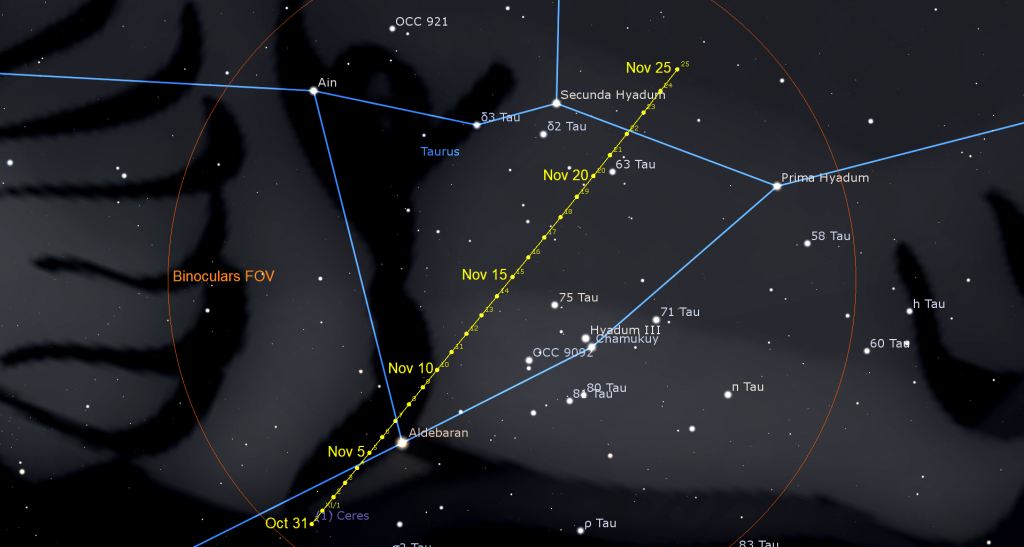

Starting on Tuesday, November 2, the orbital motion of the dwarf planet named (1) Ceres will carry it directly through the Hyades, the large open star cluster that forms the V-shaped face of Taurus (the Bull). Magnitude 6.9 Ceres is bright enough to see in binoculars and backyard telescopes. On Tuesday, Ceres, will be positioned only 7 arc-minutes (a quarter of the moon’s diameter) to the lower right of the very bright star Aldebaran. During the following weeks, Ceres will travel westward every night, eventually completely crossing the bull’s entire face diagonally.

The Water Constellations – The Lucky Stars of Aquarius

Autumn evenings feature a group of water-related constellations over the southern horizon. They aren’t very prominent – consisting mainly of dim stars – but this week’s moonless sky will offer an opportunity to see them more easily. Despite their modest appearance, you will definitely have heard of them, because they straddle the ecliptic, and are therefore zodiac constellations.

This year, Jupiter and Saturn have been travelling Capricornus (the Sea-Goat), the second dimmest constellation of the heavens, and the most westerly of the set. This week, I’ll focus on the sea-goat’s eastern neighbour Aquarius (the Water-Bearer).

Aquarius is one of the oldest recorded constellations, probably because of its place on the ecliptic / zodiac and because it re-appeared in the morning sky at the time of year that brought the return of desperately needed rains and the flooding of the Nile in ancient Egypt. It certainly was not because of its stars. The constellation is composed of about 14 modestly-bright stars with visual magnitudes that are near the limit for suburban observers.

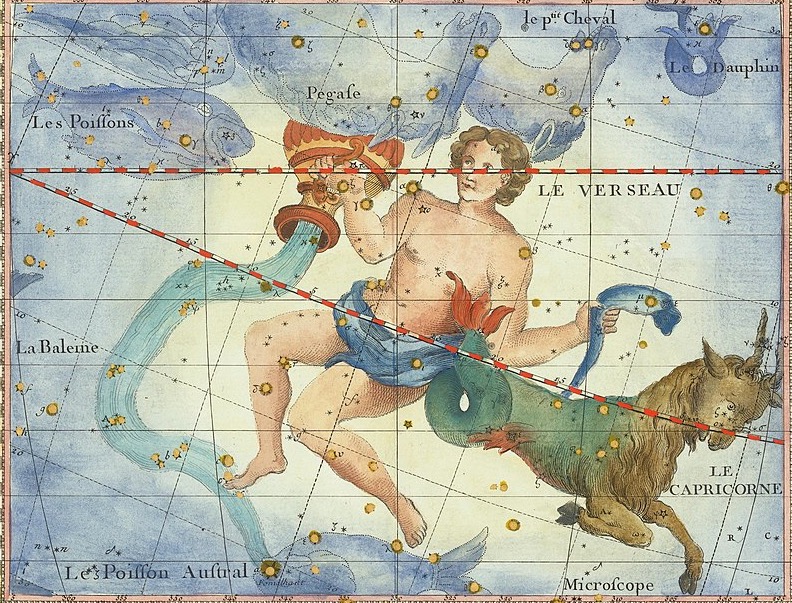

Aquarius spans an area that measures about 3.5 outstretched fist diameters wide by 2 diameters high (or 35 by 20 degrees). It is traditionally depicted as a kneeling figure, facing east, who is pouring water from a vessel. A crooked horizontal string of stars represents his right arm outstretched towards the west. To their left are the stars of his bowed head and shoulders, and finally his left hand, which bears the jug. The jug is the most easily seen part of the constellation. Descending from that line is a loose chain of stars representing the flowing water and another chain representing his torso and legs. In some stories, those stars are Zeus pouring out the water of life upon the world. In others, the waters are those of the biblical flood, a story handed down from the Sumerians. The pre-Islamic Arabs envisioned the next-door Great Square of Pegasus as al Dalw, the water well. As we’ll soon see, the stars of Aquarius are “lucky”.

By the time the sky has darkened enough to see it, Aquarius has almost completed half of its nightly trip across the sky, and is positioned due south. For mid-northern latitude observers, it’s centred midway between the southern horizon and the zenith. Since it also touches the celestial equator, Aquarius will be nearly overhead for observers viewing it from near the Earth’s equator. That celestial real estate also means that Aquarius is visible from everywhere on Earth, except the northern polar region.

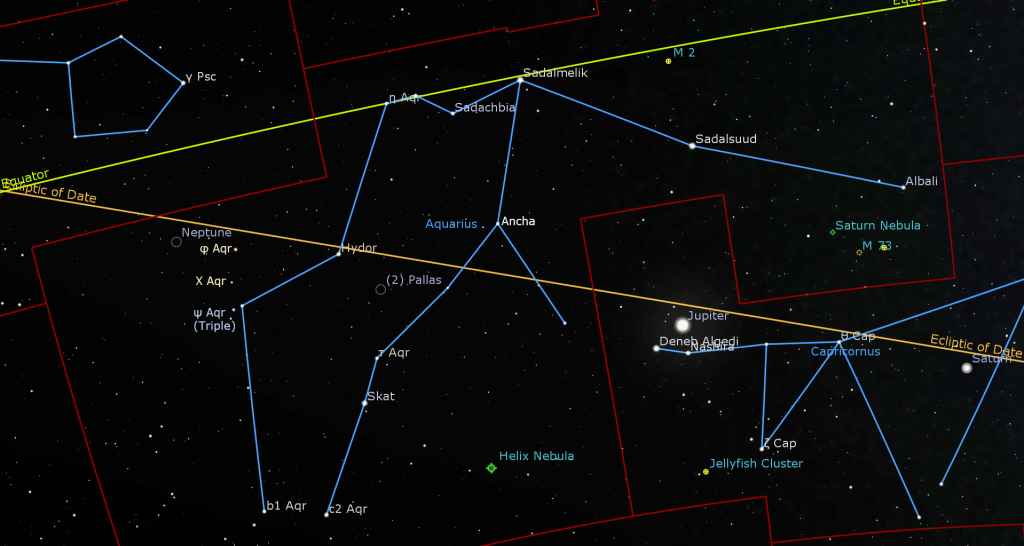

To help you find Aquarius, use the great square (or baseball diamond) of Pegasus, which sits much higher in the sky and to Aquarius’ left (i.e., to the celestial northeast). With Pegasus’ “home plate” as the bottom star, extend an imaginary line from third base to first base, and continue in the same direction by the same distance (about two fist diameters) to Aquarius’ highest and brightest star, Sadalmelik.

In a dark sky, up to 100 stars can be counted within Aquarius, but only a few are easily seen near city lights. Try to spot the four stars that extend a wide palm’s width from Sadelmalik eastward to the left. One of the four stars is a bit lower than the other three. At the eastern end of the foursome sits a modest star designated Eta Aquarii. The radiant of the springtime Eta Aquariid Meteor Shower is located close to that star.

Jumping 1.5 finger widths to the right of Eta brings us to a closely spaced double star that’s only 91 light-years away from us named Sadaltager “Luck of the Merchant”. Two finger widths to the lower right of Sadaltager is the white star Sadachbia, which comes from the Arabic phrase sa’d al-akhbiya “Lucky Stars of the Tents”. Then we hop higher again and westward to Sadalmelik, meaning “Lucky Stars of the King”. Sadalmelik is a very mature, yellow supergiant star located about 520 light-years away from us. It’s a bit cooler than our Sun, but 60 times larger in diameter, making it much more luminous.

Ten degrees (a fist’s diameter) to the right of Sadalmelik, marking the water-bearer’s elbow, sits another of the constellation’s brighter stars, Sadalsuud “Luckiest of the Lucky”. This is another yellow giant very similar to Sadalmelik and about as distant. Finally, Aquarius’ western hand is marked by a fainter, blue-white star named Albali “Good Fortune of the Swallower”, which sits a fist’s width to the lower right of Sadalsuud.

The rest of the constellation, descending in two crooked lines from the lucky stars, is fairly dim. About halfway along them, both lines take a jog to the left (east). The magnitude 3.7 star Hydor, named for the Greek word for “Water”, Hydro. Also known as Theta Aquarii, it sits where the eastern line jogs – a fat fist’s width below (or 8.6 degrees to the southeast of) Eta Aqr. Its western counterpart, below Sadalmelik, is Ancha “the Hip”.

Aim your binoculars to the lower left of Hydor and look for an up-down grouping of five medium-bright stars Psi, Chi, and Phi Aquarii (or ψ, X, and φ Aqr). Psi, the lowest, is a triple star!

Aquarius contains only a few significant deep sky objects because it is situated away from the Milky Way, our galaxy’s central plane. The bright globular star cluster designated Messier 2, which can be spotted in binoculars or small telescopes, is only 4 finger widths above (or 5 degrees to the north of) Sadalsuud. It’s 37,000 light-years away! A small planetary nebula named the Saturn Nebula (and also designated Caldwell 55) is located a similar span to the lower left of Albali. At 650 light-years away, it’s among the closest such objects to us. The huge Helix Nebula (or Caldwell 63), another planetary, is located near the lower, southerly border of the constellation. The Helix is faint, but is almost the size of a full moon! Those two stellar corpses are visible in backyard telescopes. A second, dimmer globular cluster named Messier 72 sits below and between Albali and the Saturn Nebula.

Fittingly, the planet Neptune, named for the god of the seas, has been situated in Aquarius since 2011. At present, Neptune is located less than a fist’s diameter to the left (east) of Phi Aquarii. Neptune won’t swim out of Aquarius permanently until 2024! The main belt asteroid (2) Pallas has been travelling just to the west of Hydor this month.

Halloween Treats

Last week here, I wrote about some spooky celestial treats in honour of Halloween – and we covered Halloween Astronomy during Insider’s Guide to the Galaxy – including the Ghost of the Summer Sun! Watch it on YouTube here.

Public Astro-Themed Events

Every Monday evening, York University’s Allan I. Carswell Observatory runs an online star party – broadcasting views from four telescopes/cameras, answering viewer questions, and taking requests! Details are here. Their in-person Wednesday night viewing has been converted to online via the observatory YouTube channel.

On Wednesday evening, November 3 at 7:30 pm EDT, the RASC Toronto Centre will live stream their monthly Recreational Astronomy Night Meeting at https://www.youtube.com/rasctoronto/live. Talks include The Sky This Month, stargazing with big binoculars, and using free NASA imagery. Details are here.

On Wednesday evening, November 3 at 7 pm EDT, the Perimeter Institute for Theoretical Physics will live stream a free talk by Manuel Calderón de la Barca Sánchez, physics professor at the University of California, Davis. The topic is the new film Secrets of the Universe. Details are here.

My free, family-friendly Insider’s Guide to the Galaxy webcasts with Jenna Hinds of RASC National returns on Tuesday, November 9 when we’ll cover the moon’s geology and the upcoming lunar eclipse. You can find more details and the schedule of future sessions here.

Don’t forget to take advantage of the astronomy-themed YouTube videos posted by RASC Toronto Centre and RASC Canada.

Keep looking up, and enjoy the sky when you do. I love questions and requests. Send me some!