The Terminator Tips Over, a Lonely Lunar X, and the Gibbous Moon Greets Ceres in the Winter Football!

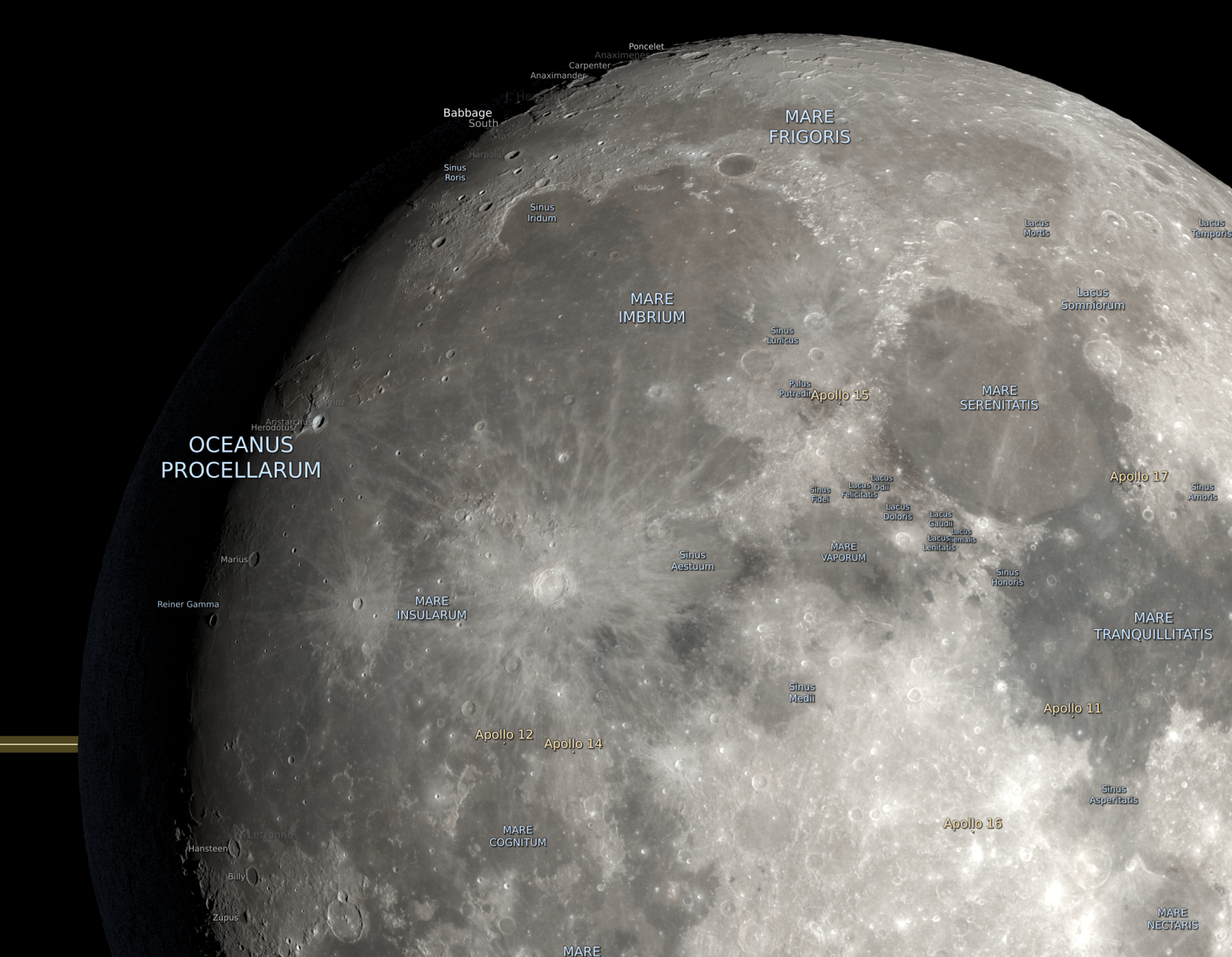

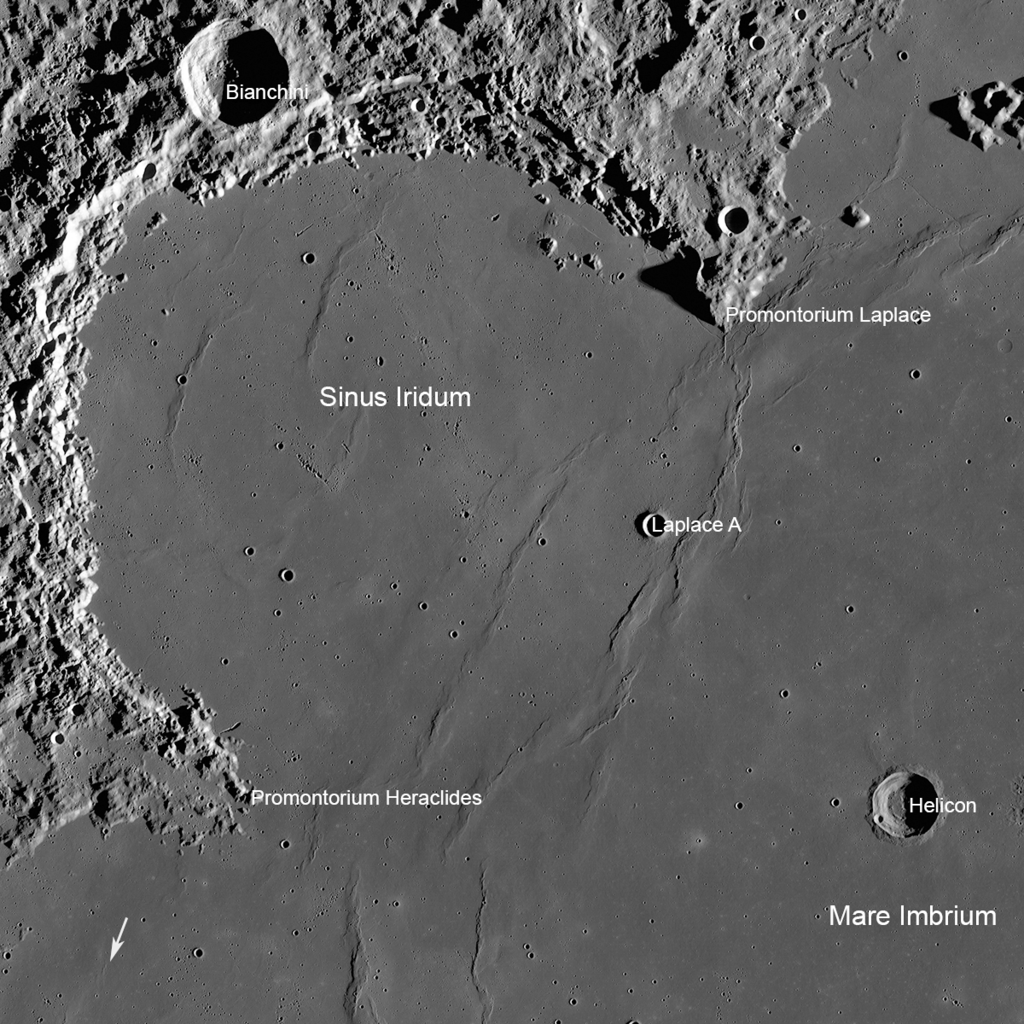

A portion of a frame from NASA’s Lunar Visualization Tool, showing the northwestern quadrant of the moon at 9 pm on January 14, 2022, annotated. The Dial-A-Moon page is at https://svs.gsfc.nasa.gov/4955

Hello, January Stargazers!

Here are your Astronomy Skylights for the week of January 9th, 2022 by Chris Vaughan. Feel free to pass this along to your friends and send me your comments, questions, and suggested topics. You can also follow me on Twitter as @astrogeoguy! Unless otherwise noted, all times are expressed in Eastern Time. To subscribe to these emails please click this MailChimp link.

If you’d like me to bring my Digital Starlab portable inflatable planetarium to your school or other daytime or evening event, or teach a session online, contact me through AstroGeo.ca, and we’ll tour the Universe, or the Earth’s interior, together! My terrific new book with John A. Read entitled 110 Things to See With a Telescope is a guide to viewing the deep sky objects in the Messier List – for both beginners and seasoned astronomers. DM me to order a signed copy!

The night sky will be dominated by the waxing gibbous moon this week. Thank goodness there is so much to see on our natural satellite! The moon will sport a Lunar X on Sunday night – the only one for the Great Lakes this year. Mercury will dance near Saturn and Jupiter in evening, and Mars will shine in the morning. Read on for your Skylights!

Sirius and the Winter Football!

If you’ve been out on a night lately, you can’t have missed the sprinkling of incredibly bright and colourful stars in the eastern evening sky. Some of the brightest stars form a huge six-sided star pattern (or asterism) called the Winter Hexagon (or Winter Football, for NFL fans).

By 8 pm local time, all of the stars that we’ll need to form the asterism are visible. The huge pattern will stand upright in the southeastern sky – extending from 14 degrees above the horizon to nearly overhead. Let’s trace it out.

The very bright, white star hugging the southeastern horizon is Sirius, nicknamed the Dog Star, in the constellation of Canis Major (the Big Dog). After our sun, Sirius is the brightest star in all the sky. Not only is it about 25 times more luminous than our sun, but it is also located a mere 8.6 light-years away! Moreover, Sirius is actually heading towards us, and will brighten in Earth’s skies during the next millennia!

Sirius is famous for exhibiting flashes of intense colour as it twinkles. This is due to combining its brightness with the extra blanket of air it must shine though when it is low in the sky. The ancient Egyptians linked their calendar to the arrival of Sirius in the pre-dawn sky because it signaled the onset of the Nile floods around the beginning of summer. In China, Sirius is called Tiān Láng天狼, aka “the Celestial Wolf”. Many First Nations cultures saw a dog’s shape in Canis Major’s stars and called Sirius the Moon Dog Star (Inuit), the Wolf Star (Pawnee), and the Coyote Star.

The constellation of Canis Major forms a very obvious dog shape – with its head upwards, its tail to the lower left, and its feet to the right (or celestial west). Moving counter-clockwise around the hexagon, look above and to the right of Sirius for the bright, bluish star Rigel, which marks the foot of Orion (the Hunter). Can you see the rather faint stars of the constellation Lepus (the Rabbit) below Rigel? The big dog is chasing it!

Almost three fist diameters above (or 26° to the celestial north of) Rigel you’ll find the orange star Aldebaran in the constellation of Taurus (the Bull). Aldebaran is an old, red-giant star more that forty times the diameter of our sun – having swelled in size as it ages.

Three fist diameters to the upper left (or 31° north) of Aldebaran sits the bright yellow star Capella, the Goat Star, in the constellation of Auriga (the Charioteer). In form, Auriga is an egg-shaped ring of medium-bright stars. Capella, at the top, might be “the diamond” in that ring. Moving three fist diameters down and to the left (or 32° southeast) of Capella we encounter a pair of bright stars – the twins Castor (higher) and Pollux (lower) in the zodiac constellation of Gemini. Castor is a pretty double star in a small telescope. The bodies of the twins extend sideways towards Orion. They’re not actually twin stars, however – Pollux is brighter and more yellowish.

On our way to completing the hexagon, look about midway between Gemini’s twins and Sirius for the bright, blue-white star Procyon in Canis Minor (the Little Dog). At only 11 light-years away, it’s another next-door neighbour! Unlike his big brother, the constellation Canis Minor has only two significant stars – Procyon, and a dim star named Gomeisa that sits four finger widths to the upper right of Procyon.

The surface temperature of stars (although they have photospheres, not surfaces) varies depending on their size, composition, and age, and this affects what colour we see them as. Our sun is a yellow star burning at about 5,500 degrees Celsius. Orange and red stars’ surfaces are cooler, with Aldebaran estimated to be at 3,600 degrees. White and blue stars are hotter. Sirius’ temperature is estimated to be nearly 10,000 degrees! One thing they all have in common – the cores inside the stars are at temperatures of millions of degrees! This is where the nuclear fusion that makes them shine is happening.

We can turn our football into a capital letter “G” by connecting Rigel to the bright, reddish star Betelgeuse (many pronounce it as “beetle juice”), which marks the eastern shoulder of Orion. This star is a true giant – believed to be more than 600 times the size of the sun! It’s also nearing the end of its life cycle. It will one day explode as a tremendous supernova; but we’re in no danger when it does since it’s so far away. Notice that Betelgeuse is not quite as strongly coloured as Aldebaran.

The Winter Hexagon is visible on the same dates and times every year, and will remain in view until about mid-April. The Winter Milky Way rises up through it – and the moon and planets wander through those stars as they travel along the ecliptic. The nearly full moon will cross through the hexagon from Friday to Sunday this week.

Don’t forget to turn and look west after dusk, there you’ll find another famous asterism, the Summer Triangle. The very bright star Vega will shine at the lower right vertex, with Altair to its lower left, and Deneb shining well above and between them. The most famous asterism of all, the Big Dipper, will be clearing the trees by around 7 pm local time and then climbing the northeastern sky for most of the night.

Lunar X Alert

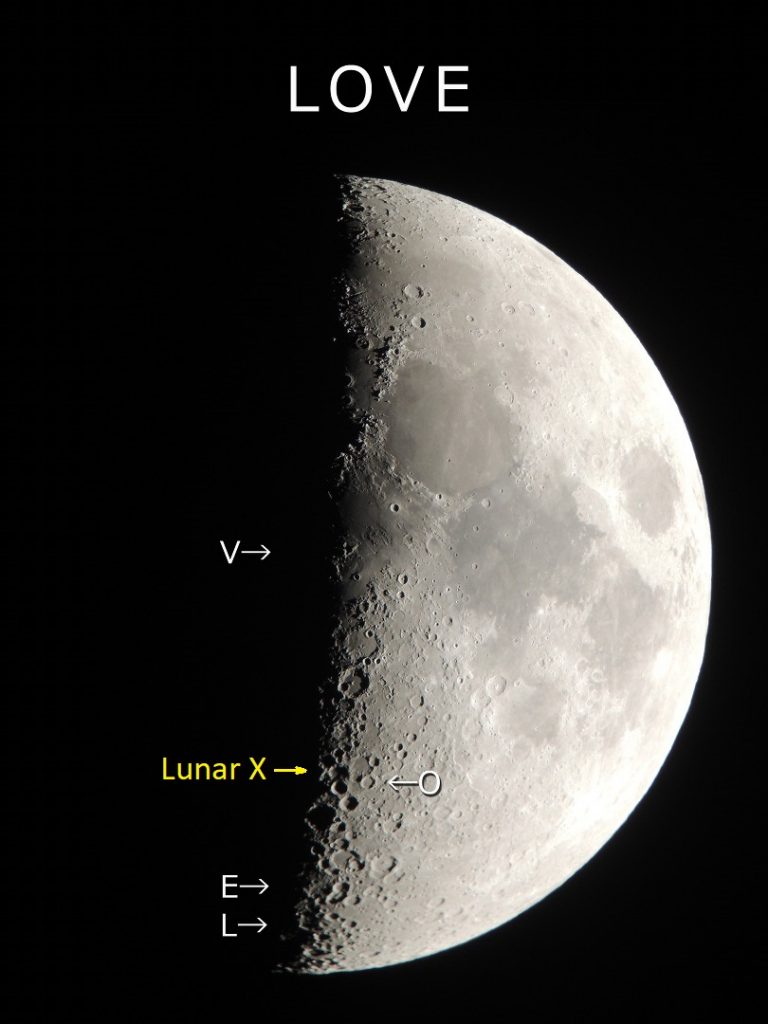

Several times a year, for a few hours near its first quarter phase, a feature on the moon called the Lunar X becomes visible in powerful, tripod-mounted binoculars and through any sized backyard telescope. When the rims of the craters Purbach, la Caille, and Blanchinus are illuminated from a particular angle by the sun, they form a small, but very obvious X-shape. On Sunday night, January 9, North Americans with clear skies will see their only Lunar X in a dark sky for all of 2022. (There will be several daytime occurrences).

The phenomenon is an example of pareidolia – the tendency of the human mind to see familiar objects when looking at random patterns. The Lunar X is located near the terminator, about one third of the way up from the southern pole of the moon (at lunar coordinates 2° East, 24° South). A prominent, round crater named Werner sits to its lower right (or lunar southeast).

The ‘X’ is predicted to start developing after 9 pm EST on Sunday night (or 01:00 Greenwich Mean Time on Monday). When the sun’s light first touches the crater rims, the X will be indistinct. The shape will intensify until around 11 pm EDT (or 03:00 GMT), and then gradually fade out over the following couple of hours. The Lunar X will be visible from anywhere on Earth where the moon is shining, especially in a dark sky, during the hours I indicated.

Observers in other time zones will have their own Lunar X events in 2022. Here is a list of the peak times for Lunar X events during the rest of this year, rounded to the nearest half-hour. If the GMT time converts to evening in your local time zone, mark your calendar!

Date Peak Time (convert to local time by adding/subtracting hours)

Feb 8, 2022 17:30 GMT

Mar 10, 2022 08:00 GMT

Apr 8, 2022 22:00 GMT

May 8, 2022 10:30 GMT

Jun 6, 2022 21:30 GMT

Jul 6, 2022 09:30 GMT

Aug 4, 2022 20:00 GMT

Sep 3, 2022 08:00 GMT

Oct 2, 2022 19:00 GMT

Nov 1, 2022 07:00 GMT

Nov 30, 2022 21:00 GMT

During a Lunar X event, you can also look for the Lunar V and the Lunar L. The “V” is produced by combining the small crater named Ukert with some ridges to the east and west of it. It is located a short distance above the moon’s equator at lunar coordinates 1.5° East, 8° North. For a further challenge, see if you can see the letter “L” down near the moon’s southern pole. Its position is to the southwest of three prominent and adjoining craters named Licetus, Cuvier, and Heraclitus which, in combination, resemble Mickey Mouse’s head and ears.

The Moon

The moon will dominate our night skies worldwide this week as it waxes from first quarter to full moon next Monday. Let’s take a peek at what you can see on our celestial sibling. Above, I highlighted the bright stars you can still enjoy under moonlight.

Today (Sunday) at 1:11 pm EST (or 18:11 Greenwich Mean Time), the moon will complete the first quarter of its orbit around Earth. At this phase, the relative positions of the Earth, sun, and moon will cause us to see the moon half-illuminated – on its eastern side. The terminator, the pole-to-pole boundary separating the moon’s lit and dark hemispheres, will make a straight line through the moon’s middle.

At first quarter, the moon always rises around noon and sets around midnight, so it is also visible in the afternoon daytime sky. If you look at the moon in mid-afternoon today, the terminator will be tilted with the top end toward the left. When the moon climbs to its highest position in the southern sky at around 6:30 pm local time today, the terminator will become vertical. During evening, the terminator will tilt to the right. And when the moon prepares to set towards midnight, the terminator will be so canted over that the moon’s lit half will be on the bottom.

The moon itself is not tilting. The effect is caused by our location on Earth combined with the change in perspective as we view the moon from a rotating Earth. You can re-create the effect by extending your left arm straight out, with your thumb parallel to the ground, i.e., pointing behind you. Without twisting your arm or wrist, swing your arm in front of you – your thumb will turn upwards. Continue the motion to the right, and your thumb will tilt to the right. Your thumb is the terminator! Constellations rotate the same way. Try it on Orion!

For the rest of this week, the terminator will shift west on the moon, filling it with light as the moon’s angle from the sun increases each day. Monday and Tuesday will be excellent nights to see the three impressive, curved mountain chains that encircle the eastern rim of dark Mare Imbrium. That giant impact basin, covering much of the north-central portion of the moon’s Earth-facing hemisphere, will be half in light and half in shadow. Those mountains, actually segments of the old crater rim, will be starkly illuminated by slanted sunlight.

The most northerly arc of mountains is the Lunar Alps, or Montes Alpes. Their peaks reach up to 2400 metres above the moon’s average surface. Use binoculars or a telescope to look for a gash cutting through them called the Alpine Valley, or Vallis Alpes. It’s a rift valley, up to 10 km wide, where the moon’s crust has dropped due to faulting. To the lower right (lunar southeast) of the Alps are the Caucasus Mountains, or Montes Caucasus. This stubby, but high (up to 6000 metres tall) mountain range disappears under a lava-flooded zone connecting Mare Imbrium with Mare Serenitatis. The mountains resume along the southeastern edge of Mare Imbrium as the lengthy Apennine Mountains, or Montes Apenninus. They, too, peter out near the prominent crater Eratosthenes, and the larger crater Copernicus beyond it. The Apennines have several large peaks reaching 5000 metres high.

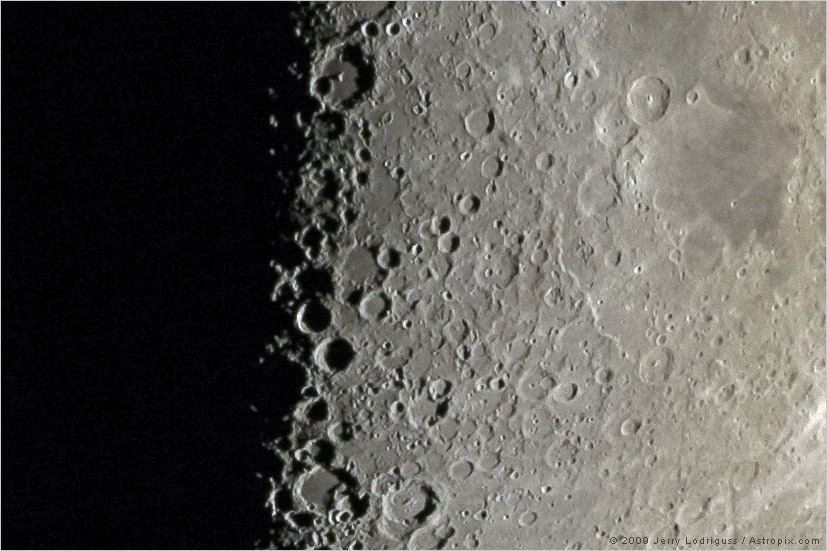

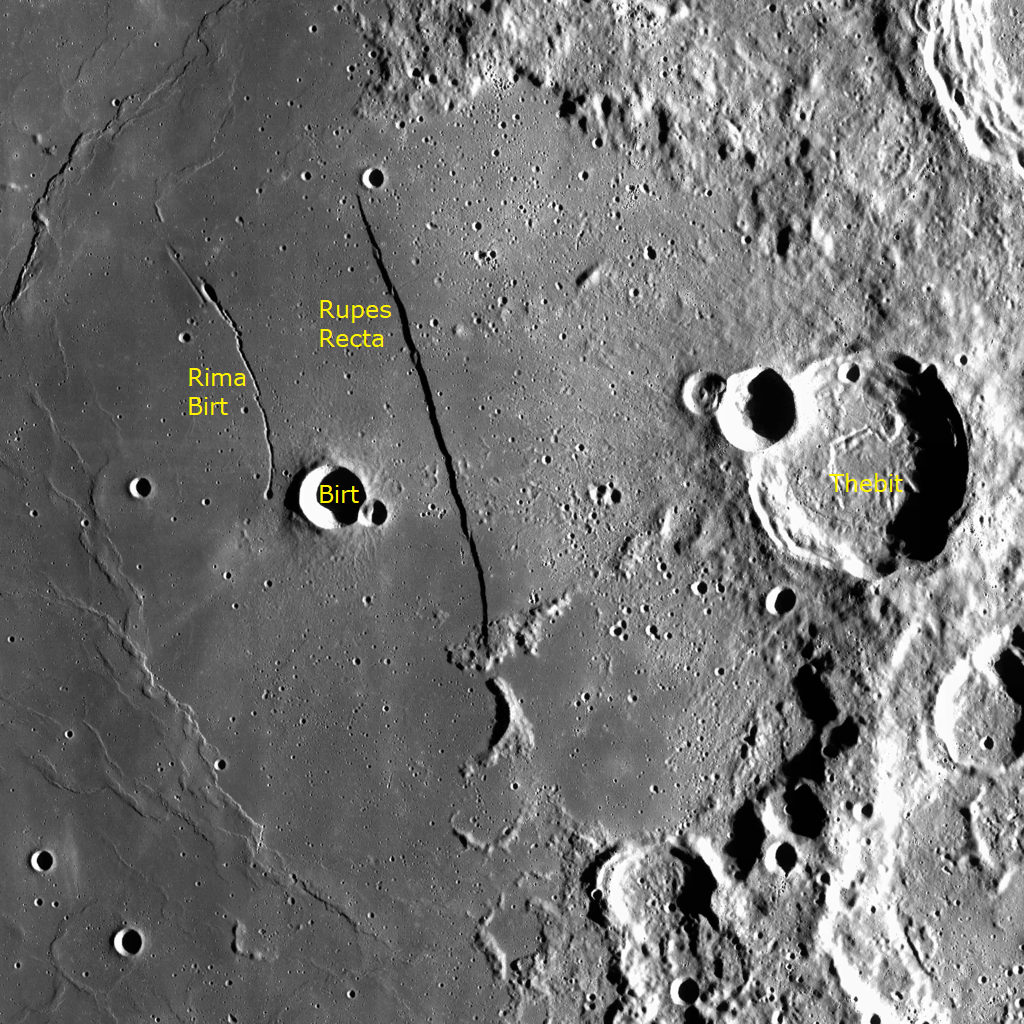

On Wednesday night, the 80%-illuminated moon will enter Taurus (the Bull) just a slim palm’s width below (or 5° to the celestial south of) the bright little Pleiades star cluster. On Tuesday and Wednesday evening, the terminator will fall just to the left (or lunar west) of Rupes Recta, also known as the Lunar Straight Wall. The rupes, Latin for “cliff”, is a north-south aligned fault scarp that extends for 110 km across the southeastern part of Mare Nubium. That’s the dark patch sitting in the lower third of the moon’s Earth-facing hemisphere. The wall, which is very easy to see in good binoculars and backyard telescopes, is located above the very bright crater Tycho.

Wednesday and Thursday night will be great for looking at the prominent crater Copernicus, located in eastern Oceanus Procellarum – which is due south of big Mare Imbrium and slightly northwest of the moon’s centre. Copernicus’ 800 million year old impact scar is visible with unaided eyes and binoculars – but telescope views will reveal many more interesting aspects of lunar geology. Several nights before the moon reaches its full phase, Copernicus exhibits heavily terraced edges (due to slumping), an extensive ejecta blanket outside the crater rim, a complex central peak, and both smooth and rough terrain on the crater’s floor. Around full moon, Copernicus’ ray system, extending 800 km in all directions, becomes prominent. Use high magnification to look around Copernicus for small craters with bright floors and black haloes around them. Impacts through Copernicus’ white ejecta blanket excavated dark Oceanus Procellarum basalt and even deeper highlands anorthosite.

On Thursday night, the terminator will fall to the left (or lunar west) of Sinus Iridum, the Bay of Rainbows. The circular, 249 km diameter feature is a large impact crater that was flooded by the same basalts that filled the much larger Mare Imbrium to its right (lunar east) – forming a rounded, handle-shape on the western edge of that mare. You can see it with sharp eyes – and easily in binoculars and backyard telescopes. The “Golden Handle” is produced when slanted sunlight brightly illuminates the eastern side of the prominent, curved Montes Jura mountain range that surrounds the bay on the top and left (north and west), and by a pair of protruding promontories named Heraclides and Laplace to the bottom and top, respectively. Sinus Iridum is almost craterless, but hosts a set of northeast-oriented dorsae or “wrinkle ridges” that are revealed under magnification at this phase. Friday night will also be good for Sinus Iridum.

On the coming weekend, the moon will be more than 95% full. Scan to the left of Copernicus for the bright craters Kepler and Aristarchus. All three of those craters are surrounded by large, but ragged rays – a combination of excavated ejecta and chains of secondary impact craters strewn on the dark lavas of Oceanus Procellarum, or the Ocean of Storms.

In 1651 the Jesuit priest Giovanni Riccioli published a labelled map of the moon. We still use his names today. He useed living and dead scientists and philosophers to name the craters, assigning ancient notables to the north of the moon and “modern” (to him, anyway) personages in the south. He placed teachers and their famous students together.

He named that dark maria for weather and states of mind, except for Mare Humboldtianum and Mare Smythii, who were famous explorers, and Mare Cognitum and Mare Moscoviense, which were discovered later on the moon’s far side. Riccioli placed the radical (but correct) proponents of the heliocentric theory for the solar system’s structure, Copernicus, Aristarchus, and Kepler in the Ocean of Storms – and he honoured fellow Jesuits Grimaldi and Clavius with prominent craters.

Don’t forget that, from Friday night to next Sunday night, the nearly full moon will be crossing through the giant Winter Hexagon or Winter Football asterism.

The Planets

After dusk for the first few nights this week, Mercury, Saturn, and Jupiter will form a neat line extending upwards to the left, along the ecliptic, starting from the west-southwestern horizon. Mercury, which reached its widest angle from the sun last Friday, and maximum visibility, will be fading in brightness, dropping sunward, and shifting to the right (celestial north) each night. The optimal viewing windows at mid-northern latitudes will be around 6 pm local time. Viewed in a telescope the planet will exhibit a waning, less than half-illuminated phase. (Ensure that sun has completely disappeared before pointing optics towards Mercury.)

Saturn, in central Capricornus (the Sea-Goat), is next in the line. Once the sky is sufficiently dark, the creamy-coloured, magnitude 0.70 planet will appear above the southwestern horizon. It will set a little before 7 pm, so don’t delay! On the evenings surrounding Thursday, January 13, speedy Mercury will move to within only a few finger widths to the lower right (or 3.5 degrees to the celestial west) of Saturn. The pair will be close enough to share the field of view in binoculars all week.

The brightest of the row of three planets, magnitude -2.1 Jupiter is among the stars of Aquarius (the Water-Bearer). The planet will set at about 8:30 pm local time – so observe it as early as you can spot it, while it’s higher. Remember to take long, lingering looks through the eyepiece – so that you can catch moments of perfect atmospheric clarity. Once Jupiter becomes too low to see in a few weeks, we’ll have to wait until August to see a bright evening planet (Saturn)! Jupiter and Mars won’t return until autumn.

Binoculars and small telescopes will show you the Jupiter’s four large Galilean moons named Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto. Since Jupiter’s axial tilt is a miniscule 3°, those moons always look like beads strung on a line that passes through the planet, and parallel to Jupiter’s dark equatorial belts. That line of moons, and the belts, tilt as Jupiter crosses the sky. The moons’ arrangement varies from night to night. Io, for example, orbits Jupiter once every 42 hours. From one night to the next night, 24 hours has elapsed on Earth – time for Io to complete half an orbit and shift from one side of Jupiter to the other. The other Galilean moons move less rapidly, taking between 3.5 and 16.7 days to orbit Jupiter. This week was the 412th anniversary of Galileo’s discovery of those moons – but he didn’t name them.

For observers in the Eastern Time Zone with good telescopes, the Great Red Spot (or GRS) will be visible while it crosses Jupiter after dusk on Thursday and Saturday, and in mid-evening on Monday. From time to time, the small, round, black shadows cast by Jupiter’s Galilean moons become visible in amateur telescopes when they cross (or transit) the planet’s disk. On Tuesday evening, January 11, observers in the Americas with telescopes can watch the round shadow of Jupiter’s moon Europa cross the planet between 5:05 pm EST and 7:45 pm EST (or 21:05 and 23:45 GMT).

Distant, dim Neptune is in the evening sky, too – near the border between Aquarius (the Water-Bearer) and western Pisces (the Fishes). The magnitude 7.9 planet is almost two fist diameters to the upper left (or 19° to the celestial east) of Jupiter. Try to view Neptune in early evening, while it sits higher in the sky. It’ll set around 10 pm local time.

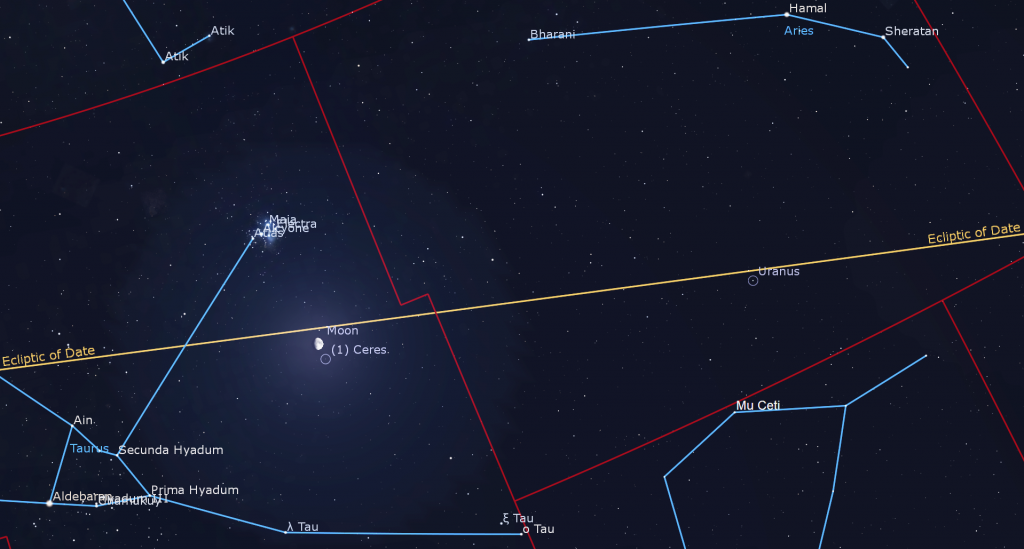

Uranus is shining at magnitude 5.7. Look for the planet’s small, blue-green dot moving slowly retrograde westwards in southern Aries (the Ram), a fist’s width below (or 11.5 degrees southeast of) that constellation’s brightest stars, Hamal and Sheratan. Or use binoculars to locate Uranus using the nearby star Mu Ceti. Uranus is also about 1.6 fist diameters to the upper right (or 16 degrees to the celestial west-southwest) of the Pleiades star cluster. This week Uranus will be observable for most of the night – especially around 7:30 pm local time, when it will have climbed more than halfway up the southern sky.

About 1.7 fist diameters farther east, towards the Pleiades cluster and the bright, reddish star Aldebaran in Taurus (the Bull), you’ll find the dwarf planet named (1) Ceres. On Wednesday evening, the orbital motion of the waxing gibbous moon will carry it very close to Ceres, the largest object in the belt between Mars and Jupiter, and the first asteroid discovered. In 2006, Ceres was reclassified as a dwarf planet. After dusk, the moon will be positioned in the southeastern sky with the tiny dot of magnitude 8.0 Ceres situated less than a lunar diameter below it, i.e., to the celestial SSE. For best results, hide the bright moon outside of the top of your field of view of binoculars. The duo will be telescope-close, too – but your optics will flip and/or invert the scene. Over the course of Wednesday night, the moon’s separation above Ceres will increase to several finger widths. Next Sunday, the motion of (1) Ceres across the background stars will pause while it completes a retrograde loop that began on October 8, 2021. Retrograde loops are tricks of parallax caused when Earth, on the inside track around the sun, overtakes a more distant object. They last for several months.

Early risers can watch for Mars, which will continue its year-long journey to a bright showing at opposition in December, 2022. Mars will rise at about 5:45 am local time. You might spot the magnitude 1.48 planet shining low in the southeastern sky, well to the lower left of its rival, the bright star Antares in Scorpius (the Scorpion) until about 7 am local time. Take care to turn binoculars and telescopes away from the eastern horizon well before the sun rises.

Public Astro-Themed Events

Every Monday evening, York University’s Allan I. Carswell Observatory runs an online star party – broadcasting views from four telescopes/cameras, answering viewer questions, and taking requests! Details are here. Their in-person Wednesday night viewing has been converted to online via the observatory YouTube channel.

On Tuesday, January 11 from 7 to 8 pm EDT, the Dunlap Institute at University of Toronto will stream their popular Astro Trivia Night. The live free event will feature lots of fun and prizes. Details are here. Watch it here.

On Thursday, January 13 at 8 pm EDT, the Dunlap Institute at University of Toronto will stream their AstroTour. The live free event will feature Ajay Gill discussing Cosmology with Galaxy Clusters. Details are here.

RASC’s in-person sessions at the David Dunlap Observatory may not be running at the moment, but they are pleased to offer some virtual experiences instead, in partnership with Richmond Hill. The modest fee supports RASC’s education and public outreach efforts at DDO. On Saturday night, January 15 from 7 to 8:30 pm EST, tune in for Up in the Sky. During the family-friendly session, RASC astronomers will live-stream views through their telescopes and the giant 74” telescope at DDO (pre-recorded views will be used if skies are cloudy). Only one registration per household is required. Deadline to register for this program is Wed., January 12, 2021 at 3 pm. Prior to the start of the program, registrants will be emailed the virtual program links. The registration link is here.

On Sunday afternoon, January 16 from 1 to 2 pm EDT, join me for Ask an Astronomer. During these family-friendly sessions, I’ll answer your questions about the universe and review what’s up nowadays. Only one registration per household is required. Deadline to register for this program is Wed., January 12, 2021 at 3 pm. Prior to the start of the program, registrants will be emailed the virtual program links. The registration link is here.

My free, family-friendly Insider’s Guide to the Galaxy webcasts with Samantha Jewett of RASC National return on Tuesday, January 18 at 3:30 pm EST, when we’ll talk about Observing Programs and the certificates and pins you can earn for completing them. You can find more details and the schedule of future sessions here.

Don’t forget to take advantage of the astronomy-themed YouTube videos posted by RASC Toronto Centre and RASC Canada.

Space Station Flyovers

The ISS (or International Space Station) will not be visible over the GTA this week. My Insider’s Guide to the Galaxy session about satellites is on YouTube here.

Keep looking up, and enjoy the sky when you do. I love questions and requests. Send me some!