Venus is Globular, Jupiter Reaches Opposition, Mars Reverses near the Bees, a Picturesque Moon Occults Saturn, and we Peruse Perseus!

This image of the Fossil Footprint Nebula NGC 1491 in Perseus was captured by Adam Block at Mount Lemmon Observatory in Arizona. This image is nearly one degree wide, or about one finger’s width. (Wikipedia)

Happy December, Stargazers!

Here are your Astronomy Skylights for the week of December 1st, 2024 by Chris Vaughan. Feel free to pass this along to your friends and send me your comments, questions, and suggested topics. You can also follow me on Twitter as @astrogeoguy! Unless otherwise noted, all times are expressed in Eastern Time. To subscribe to these emails please click this MailChimp link.

If you’d like me to bring my Digital Starlab portable inflatable planetarium to your school or other daytime or evening event in Simcoe, Grey, and Bruce Counties, or deliver a virtual session anywhere, contact me through AstroGeo.ca, and we’ll tour the Universe, or the Earth’s interior, together! My book with John A. Read entitled 110 Things to See With a Telescope is a guide to viewing the deep sky objects in the Messier List – for both beginners and seasoned astronomers. DM me to order a signed copy!

The moon will gradually become bright enough to spoil stargazing this week, but we have time to peruse the stars of Perseus and view some lunar features. The busy planets have Venus passing a globular cluster, Saturn getting occulted by the moon, Mars starting a retrograde loop near the Beehive Cluster, and Jupiter reaching opposition while Mercury hides beside the sun. Read on for your Skylights!

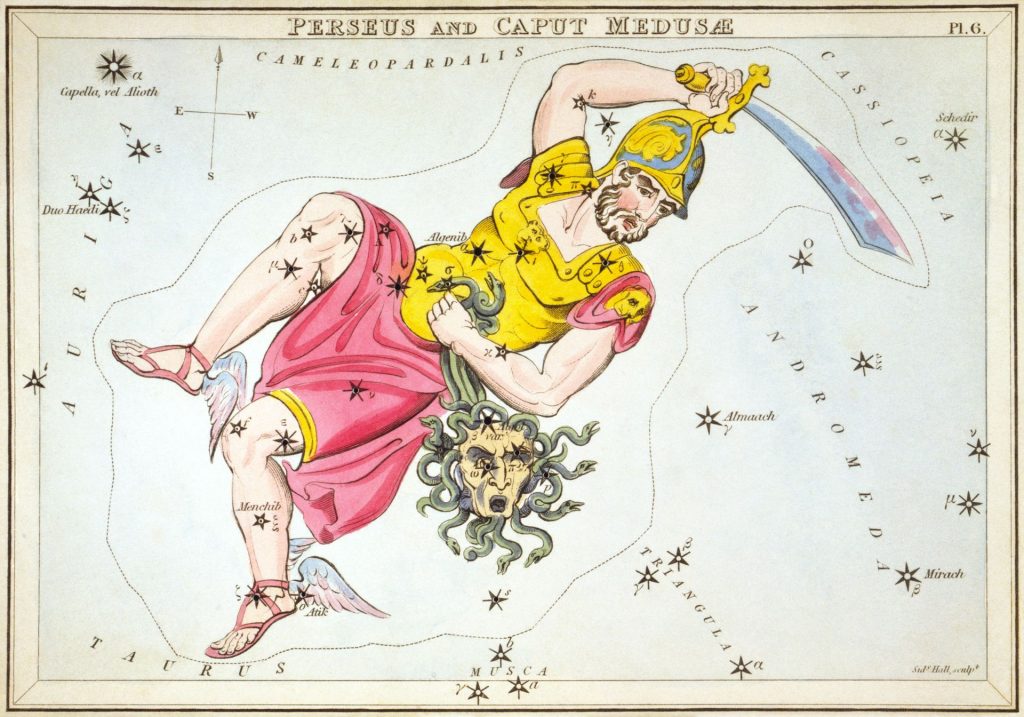

Perusing Perseus

Fall and winter evenings host the constellations involved in the Greek mythology story of Perseus (the Hero) and Andromeda (the Princess). Last week here I told the Perseus and Pegasus part of the story and toured Pegasus’ stars and deep sky objects. The moon won’t affect stargazing too much until the coming weekend, so let’s focus on the hero Perseus and his story. Once upon a time…

Andromeda was the beautiful daughter of Queen Cassiopeia and King Cepheus of Ancient Aethiopia. The regal duo are side-by-side constellations in the northern sky and circumpolar (i.e., they never set) for observers living north of the latitude of St. Louis, Missouri, Seoul, South Korea, and Athens, Greece.

After her mother angered the Nerieds (Sea Nymphs) by boasting of Andromeda’s unrivaled beauty, the god of the sea Poseidon (aka Neptune) sent Cetus, the Sea-monster to ravage Aethiopia’s coast. An oracle King Cepheus consulted told him that his only remedy was to sacrifice Andromeda to Cetus. So she was chained to rocks by the sea-shore…

Meanwhile, King Polydectes of Seriphos had sent the hero Perseus to retrieve the head of the snake-headed Gorgon named Medusa. Before hunting Medusa, Perseus was given some magical gifts to aid him in his quest, including winged silver sandals called the Shoes of Swiftness. Immediately after slaying Medusa by cutting off her head, he flew into the air to avoid her two angry sisters. While hovering there, some of the gorgon’s blood dripped onto the seashore below. Poseidon, god of the Sea, mixed the blood with some sea foam, and the magical flying horse Pegasus, whose name is related to the Greek word for wellspring “pegai”, sprang from the sea.

Perseus, using his winged sandals to fly back to Seriphos, happened to spot Andromeda just as Cetus was about to take her. She must have been beautiful indeed, because he instantly fell in love with her, slew the beast, and freed her from her chains. After more adventures, including one in which Perseus accidently killed his evil grandfather to fulfill a prophecy, the couple sailed to Argonis, where they raised a family of many children. Hercules, yet another constellation in western astronomy, was descended from them.

Perseus, whose name shares a root with the Persians, is one the 48 ancient constellations described by the Greek astronomer Ptolemy in the 2nd Century. His stars are centred midway between the Celestial Equator and Polaris – so part of him is circumpolar for mid-northern latitude observers. The entire constellation can be seen as far as 30° S latitude on Earth, but only during evenings from November to January, when he peeks above the northern horizon there.

Perseus’ main stars are enclosed in a square spanning about 26° north-to-south and 22° east-to-west. A peninsula appended to his northwestern corner adds to his territory. Perseus is bordered by the prominent constellations of Taurus and Aries on the south, Auriga on the east, and Andromeda’s mother Cassiopeia to the northwest. Triangulum and Andromeda’s feet are due west of him. The faint stars of Camelopardalis (the Giraffe) lay to his northeast.

In the evening during early December, Perseus is located relatively high in the northeastern sky. The easiest way to identify the constellation is to look for Perseus’ brightest star Mirfak, which shines midway between the W-shape of Cassiopeia and the even brighter, yellowish star Capella in Auriga (the Charioteer) below it. Once you have Mirfak, which represents the hero’s heart, look for two more stars extending a line towards Cassiopeia. They trace out his neck and head. To the lower right of Mirfak, you’ll see a lengthy chain of medium-bright stars that arc downwards towards the bright Pleiades star cluster in Taurus (the Bull). Those stars represent Perseus’ torso and eastern leg. His western leg is composed of another chain of stars that begins at a grouping representing Medusa’s head. (She’s slung on his hip or held in his western hand.) That leg curves northeast, passes above Mirfak, and converges towards his head. In the sky, the two arcs appear as a narrowing wedge which points toward the bottom end of the queen’s W.

Since the two chains of stars resemble legs, many cultures saw a human figure in them. In contrast, Asian astronomers saw a boat’s keel formed by the lower (eastern) curve of stars, the Egyptians saw a bird, and the Romanians saw a mighty axe called Barda.

Mirfak or Alpha Persei (α Per) is a golden, F5-class supergiant star located about 510 light-years from Earth. The name has been shortened from the Arabic expression Marfik al Thurayya, “the Elbow Nearest to the Many Little Ones”, referring to the Pleiades star cluster by their Arabic name, al Thurayya. Mirfak is several thousand times more luminous than our sun and about 42 times larger. It is an elderly, yellow supergiant star that has evolved out of its blue phase and is now fusing helium into carbon and oxygen in its core. Some ancient star charts labelled Mirfak as Algenib, from Al Janb “the Side” – but that name is nowadays used for Gamma Pegasi, the southeastern star in Pegasus’ Great Square.

Mirfak shines at the upper (northwestern) edge of a large and loosely scattered cluster of about 100 hot, bright, blue-white B and A-class stars known as the Alpha Persei Moving Group, the Perseus OB Association, and Melotte 20. Those stars are siblings of Mirfak – born from the same molecular hydrogen cloud about 41 million years ago – and now travelling through the galaxy together with Mirfak. The open star cluster, which is sprinkled across 3 degrees of the sky, can be seen with unaided eyes, and looks wonderful in binoculars.

Let’s inspect Perseus’ lower (easterly) chain of stars. The medium-bright star positioned several finger widths below (southeast of) Mirfak is Delta Persei (δ Per). It’s an outlying member of the OB Association. In a telescope, Delta Persei will split into a close double star pair. Some star charts depict Delta as Perseus’ eastern shoulder. A chain of half-as-bright stars, each about a thumb’s width apart, form his arm, which curves downwards (to celestial east). In order, those stars are c Persei, Mu Persei (μ Per), b Persei, and Lambda Persei (λ Per).

Two relatively bright open star clusters named NGC 1528 and NGC 1545 are positioned within a finger’s width of the star b Perseii – one to the upper left and one below it, respectively. Together, they are named the m & m Double Cluster. Less than a finger’s width to the upper left (celestial north of) Lambda Persei sits a beautiful clump of glowing gas with embedded stars called the Fossil Footprint Nebula or NGC 1491. In long exposure images it reaches the size of the full moon. Several more star clusters are in the same area. Scan around with your binoculars!

Resuming our tour back at Delta Persei, look nearly a fist’s diameter to the lower right for the star Epsilon Persei (ε Per), and then continue right for a few more finger widths to the less-bright star Menkib or Xi Persei (ξ Per), so named from the expression Mankib al Thurayya “shoulder of the Pleiades”. Menkib is a blue supergiant star, 12,700 times brighter than our sun. Its photosphere’s temperature of 35,000 K makes it one of the hottest stars you can see with your unaided eyes. The radiation from Menkib is causing the hydrogen gas in a nearby cloud to glow with red light, producing the gorgeous California Nebula, or NGC 1499. The very faint, elongated nebula, which stretches up-down just to the left of Menkib, covers a patch of sky larger than 1 x 5 moon diameters! A palm’s width below (or 6.4 degrees to the celestial east) of Menkib is a much smaller, but brighter glowing gas region called the Northern Trifid Nebula (NGC 1579), so-named because strips of dark foreground dust have separated the gas into lobes.

From Menkib we slide right (celestial south) by several finger widths to Zeta Persei (ζ Per), a bright star that marks Perseus’ eastern foot. Zeta is about 750 light years from us. In a telescope, look for two tiny stars huddled close together just to the lower right of it – its travelling companions. Two finger widths to the upper right (west) of Zeta, look for the medium-bright, white star named Atik or Omicron Persei (ο Per). Its name comes from Al Atik “the shoulder” – although I see it as the wing of his sandal.

Atik is part of a multiple star system. Under high magnification in a telescope it splits into a close together pair of stars. Binoculars should show you a little clump of stars below the pair, an open cluster named IC 348. A star named V718 Persei inside of IC 348 appears to be periodically eclipsed by an orbiting giant exo-planet every 4.7 years. Long exposure photos will reveal a large halo of blue nebulosity around both Atik and that cluster. Similar to the Pleiades, the glow is starlight scattering from interstellar dust in the foreground. The sky between Zeta Persei and Atik is sprinkled with little stars that show well in binoculars. Another pretty knot of glowing gas and stars named the Embryo Nebula (NGC 1333) is located a few finger widths to the upper right of Atik.

Starting back at our home base, bright Mirfak, let’s now travel up to Perseus’ head, towards Cassiopeia. Four finger widths to the upper left of Mirfak we find medium-bright, yellow Gamma Persei (γ Per), a sun-like star. Some charts label it Al Fakhbir or Alphecher, from the Arabic for “the Excellent One”. Gamma is an eclipsing binary star system that diminishes a little bit in apparent brightness for two weeks every 14.6 years. Thinking of Gamma as Perseus’ eastern eye, or ear, the less-bright, orange-tinted star shining a few finger widths to Gamma’s upper left marks the top of the hero’s head. That’s Eta Persei (η Per), sometimes called Miram. It’s located about 1,300 light-years away from us. Look for a faint white companion star nearby. Meteors from the annual Perseids Meteor Shower appear to radiate from a point in the sky near this star because Earth is traveling in that direction during the shower’s peak hours.

The sky several finger widths above Miram contains the bright Double Cluster. Those two open star clusters, each 0.3 degrees across and approximately 0.45 degrees apart, form a spectacular one-finger-wide sight in binoculars or a telescope at low magnification. (That’s twice the width of the full moon!) The higher, more westerly cluster NGC 869 is slightly closer to Cassiopeia. It is more compact, and contains more than 100 white and blue-white stars. NGC 884, the lower, easterly cluster, is a bit sparser and contains a handful of 8th magnitude golden suns. Zoom in close with your telescope to see their double stars, mini-asterisms, and dark lanes of missing stars. The two clusters formed inside the Perseus Arm of our Milky Way galaxy, about 7,300 light-years from the sun. Their visual brightness has been dramatically reduced by opaque interstellar dust in the foreground.

Shifting to the right (celestial south) by a few finger widths from Eta, we find the hero’s western eye, or ear – the star Kerb or Tau Persei (τ Per). As with Gamma below it, Tau is a G8-class, sunlike star. It has the same familiar yellowish tint, but shines only half as brightly as Gamma. It’s another eclipsing binary system, with a period of 4.15 years. Use your binoculars to look for a star located a finger’s width to the lower right of Tau Persei. In a telescope, that star divides into a close together pair, the double star named Struve 331 or Σ331! (The name comes from father and son astronomers Friedrich Georg Wilhelm von Struve and Otto Wilhelm von Struve, who catalogued double stars.)

Continuing down and to the right from Kerb brings us to medium-bright Iota Persei (ι Per). It’s another yellow star, positioned about two finger widths above Mirfak. Extend the line from Mirfak upwards through Iota and beyond to trace out a long, bent row of stars, all of about the same brightness, that represent Perseus’ western arm or outstretched sword. It continues with Theta Persei (θ Per) about a palm’s width above Mirfak. From Theta, look a few finger widths to the upper left for the widely spaced trio of stars named 64, 65, and 66 Andromedae (the border with Andromeda jogs left and right in this area so they are assigned to her). After passing a solitary star named 6 Persei, Perseus’ arm ends a palm’s width beyond the trio at the medium-bright, white star Phi Persei (φ Per). That’s a total length of 1.4 fist diameters (14 degrees). Phi has a fainter reddish companion sitting just to the upper right it. A finger’s width below Phi (or 0.9 degrees to the north-northwest) you’ll find Messier 76, also known as the Little Dumbbell Nebula. It’s a planetary nebula – the corpse of a star with the mass of our sun that blew off its outer layers at the end of its life. This little gem, 5600 light-years distant, can be seen in a backyard telescope under dark skies.

Returning your steps back to Iota Persei, shift your gaze four finger widths to the right (south) to yellow-orange Kappa Persei (κ Per). At 112 light-years away, it’s among Perseus’ closest stars to Earth. Its traditional name Misam comes from the Arabic miʽṣam “wrist”. It has evolved from a sunlike G-class star into a red giant fusing helium in its core. It may actually have been ejected from the Pleiades or Hyades clusters to the south! NGC 1245, a nice open cluster, the same size as the moon, is located just a finger’s width below the midpoint between Iota and Kappa. Its nickname, the Patrick Starfish Cluster, comes from the TV show SpongeBob Squarepants.

The bright star positioned a few finger widths to the right (or 4 degrees to the celestial south of) Kappa, and almost a fist’s diameter to the right of Mirfak, is Beta Persei (β Per), better known as Algol, from the Arabic expression Ra’s al-Ghul, which means “the Demon’s Head”. The star represented the god Horus in Egyptian mythology and was Rosh ha Satan “Satan’s Head” in Hebrew. Before we focus our attention on Algol and the stars forming Medusa’s head, aim your binoculars or telescope four finger widths above (celestial northwest) Algol and look for the big and bright open star cluster Messier 34, also called the Spiral Cluster and NGC 1039. Many of its brightest stars are arranged in curved chains, hence the nickname.

The area around Algol is littered with distant galaxies! A galaxy cluster named the Perseus Cluster or Abell 426 contains thousands of them, including an active peculiar galaxy named NGC 1275 or Perseus A that is the brightest object in X-ray wavelengths in the entire sky, despite it being more than 225 million light-years away! NGC 1275 and some of the galaxies near it are visible in larger backyard telescopes and long exposure photographs. The cluster is centred two finger widths to the lower left (celestial east-northeast) of Algol.

Algol is among the most accessible variable stars for beginner skywatchers. Like clockwork, this star’s visual brightness dims noticeably once every 2 days, 20 hours, and 49 minutes. That happens because a dim companion star orbiting nearly edge-on to Earth crosses behind the much brighter main star. Once the eclipse begins, the light we see steadily drops in brightness for five hours. Then it ramps up again during another five hours – until the eclipse is over. Algol is the archetype for all eclipsing binary star systems.

Algol represents the pulsing eye of Medusa the Gorgon, whose severed head Perseus is carrying, hence its scary nickname. Yet another name for Algol is Gorgonea Prima “the First Gorgon”. The star that sits two finger widths to the right of Algol is Gorgonea Tertia “the Third Gorgon” or Rho Persei (ρ Per). In binoculars, that star appears markedly red due to its cool, M4-class spectrum. Gorgonea Secunda “the Second Gorgon” and Gorgonea Quarta “the Fourth Gorgon” are the stars Pi Persei (π Per) and Omega Perseii (ω Per). They are located to the upper right and lower right of Algol, respectively. The four Gorgonea stars combine to form Medusa’s box-shaped head. Algol is located about 90 light-years from Earth – but the other three stars are all about 300 light-years distant.

The easiest way to detect Algol’s variability is to note how bright that star looks compared to other, non-varying stars near it. When it isn’t dimmed, Algol is as bright as Almach, the bright star located a fist’s diameter above Algol (or celestial west) in Andromeda. Although Gorgonea Tertia (Rho Persei) is somewhat variable, too – it’s pulsing due to old age – Algol shines at about the same brightness while dimmed. Going forward, I’ll let you know when Algol’s dimming happens at convenient times.

The next few months will be a great time to explore Perseus, Andromeda, Cassiopeia, and the other story characters Cepheus and Pegasus. Just gaze up at their stars on a dark night, or use any binoculars or a backyard telescope to zoom in on their treasures.

The Moon

After being absent for a while, the moon will return to shine in the western sky in the evening the world over this week. But the early sunsets for northerners means that it won’t hinder our stargazing very much until late this week.

Our natural satellite passed its new moon phase last night. Observers living near the tropics and in the Southern Hemisphere might see the extremely thin crescent moon sinking above the southwestern horizon after sunset today (Sunday) and Monday, but the rest of us will need to wait until Tuesday, when the moon will shine prettily well to the lower right of the brilliant planet Venus.

The moon will wax in phase and linger an hour longer after sunset every night. As the sky is darkening after sunset on Wednesday, look low in the southwest to see the pretty, waxing crescent moon shining just below (or several degrees to the celestial south of) Venus. The pair will be cozy enough to share the view in binoculars and will make a pretty photo until they drop into the trees around 6:30 pm local time. By then the stars will be out.

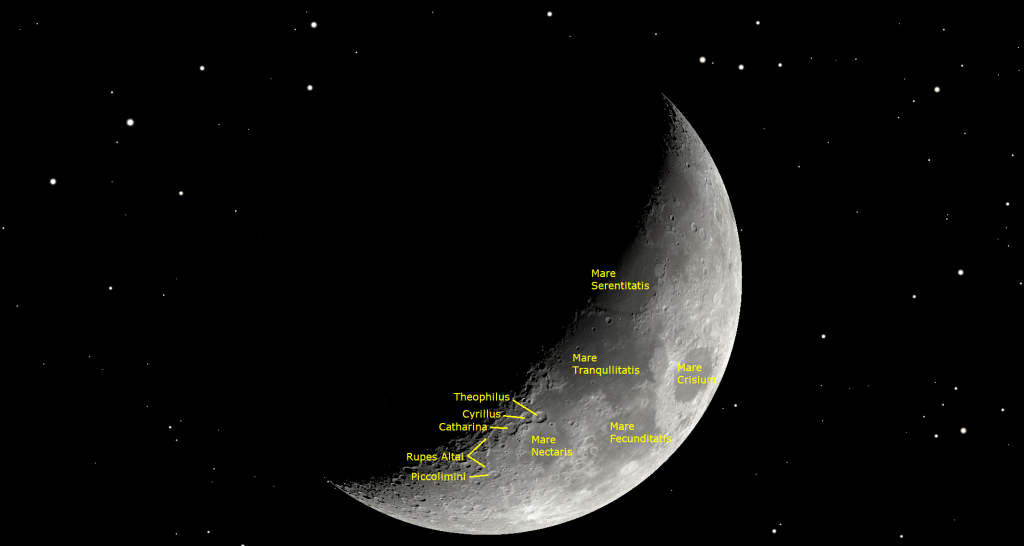

This part of the moon’s 29.5-day cycle, or lunar month, will be the best period for viewing it. While your unaided eyes will be able to appreciate its poetic crescent and its larger features in patterns of dark and light, any amount of magnification will reveal breathtaking vistas, especially along the sunny side of the curved, pole-to-pole lunar terminator. That’s where the sun is just clearing the horizon, and the sunlight is near-horizontal.

Wednesday’s crescent will be anchored by the dark oval of Mare Crisium., the “Sea of Crises”, with dark, blotchy Mare Fecunditatis, “the Sea of Fertility” to its lower left. On Thursday, the slightly fuller crescent will shine within the bounds of Capricornus (the Sea-Goat) and to the upper left of Venus. That evening, the terminator will arc just to the left (or lunar west) of ancient Mare Nectaris, the dark and roughly circular patch located just south of the moon’s equator. A prominent crater named Piccolomini is located in the lunar highlands a small distance to the lower left of Nectaris. The 88 km wide crater has a sharp rim and a tall central mountain peak. A backyard telescope will show that the central peak is complex and that the crater’s inner walls have collapsed to form terraces.

Come back to it on Friday to see the curved escarpment named Rupes Altai extending to the upper left (or lunar northwest) from Piccolomini. Piccolomini and are Nectaris are highlighted during evening every lunar month when the waxing moon is about 5 days past new and again before sunrise when the waning moon is approaching third quarter.

Friday evening’s terminator will also fall just to the left of a trio of large craters named Theophilus, Cyrillus, and Catharina that curve along the western edge of Mare Nectaris. You can tell in what order the craters were formed in by observing how sharp and fresh Theophilus’ rim appears, and by the way it has partially overprinted neighboring Cyrillus to its lower left (or lunar southwest). Under magnification, Theophilus’ terraced rim and craggy central mountain peak are evident. Cyrillus hosts a trio of degraded central peaks inside a hexagonal rim, while much older Catharina’s peak has been submerged, her edges blurred and her floor overprinted by smaller, more recent craters.

Friday’s moon, still residing in Capricornus, will drop below the rooftops and trees by about 8:45 pm, leaving the rest of the night moonless and dark. On Saturday evening in the Americas, the waxing and just shy of half-full moon, will shine a palm’s width to the lower right (or celestial west) of Saturn while both shine in Aquarius (the Water-Bearer). The pair will be due south after dusk and then set in the west towards 11 pm local time.

The moon will complete the first quarter of its trip around Earth on Sunday morning in the Americas. On Sunday night, the half-illuminated first quarter moon will hop east to shine to Saturn’s upper left. In the interim, observers located in a zone extending from eastern Indonesia and the Philippines, and northeast across most of Japan to the Aleutian Islands can see the moon cross in front of (or occult) Saturn on Sunday evening. Use a stargazing app to look up the occultation timings for your specific location.

The Planets

Four of the five bright planets – and both of the fainter, farther ones – will be visible in the evening sky this week.

Venus is the very bright “star” gleaming in the southwestern sky at sunset every night. Now that it has been lifted a little higher by its increasing angle away from the sun and by the plane of the solar system rotating to a more vertical orientation, you can hardly fail to miss it! Venus will begin in a twilit sky, but the stars will appear around it by the time it sets around 7:45 pm local time. On Friday Venus will slip from Sagittarius (the Archer) into next-door Capricornus (the Sea-Goat). The pretty crescent moon will pose below it on Wednesday.

Through a telescope, or very strong binoculars, Venus will show a waning gibbous phase. On the evenings surrounding Friday, December 6, the eastward orbital motion of the bright planet will cause it to pass a small distance from the distant globular star cluster designated Messier 75. From Thursday to Saturday they’ll be tightly spaced enough to share the view in a telescope eyepiece, but the far fainter cluster will be easier to see if you hide Venus just outside the field of view. For observers located closer to the tropics or in the Southern Hemisphere, the duo will be higher and in a dark sky. As a bonus, during the same few nights, the minor planet Ceres, named for the Greek goddess that gave us the word “cereal”, will be passing less than a palm’s width to Messier 75’s lower left (or ~5.5° to the celestial south).

Even before the sky gets very dark, turn south to spot the yellowish dot of Saturn shining not too high up in the sky. In a dark sky, you might also see the bright star Fomalhaut in the constellation of Piscis Austrinus (the Southern Fish) twinkling about two fist diameters below, and a little to the right, of Saturn. Saturn and the faintish stars of Aquarius (the Water-Bearer) surrounding it will set the west around midnight local time, but you’ll have clear views of the planet in any backyard telescope until about 10 pm. Don’t forget that the pretty moon will shine near the ringed planet (and occult it for parts of the world) on Friday-Saturday.

Saturn’s bright, but extremely thin rings effectively disappear when they become edge-on to Earth every 15 years. Since we are only four months away from that, in late March, 2025, the rings already appear as a thick line drawn through the planet. Good binoculars can hint that Saturn has rings, but any size of telescope will show the rings and some of Saturn’s larger moons, too. In most years, Saturn’s moons are sprinkled around the planet, unlike Jupiter’s Galileans moons, which are always in a line. But while Earth is within months of being aligned with Saturn’s ring plane, its moons remain within a zone drawn through the rings.

Saturn’s largest and brightest moon Titan “TIE-tan” never wanders more than five times the width of Saturn’s rings from the planet. The much fainter moon named Iapetus “eye-YA-pet-us” can stray up to twelve times the ring width during its 80-day orbit of Saturn. The next brightest moons Rhea “REE-ya”, Dione “Dee-OWN-ee”, Tethys “Teth-EES”, Enceladus “En-SELL-a-dus”, and Mimas “MY-mass” all stay within one ring-width of Saturn. You may be surprised at how many of those six you can see through your telescope if you look closely when the sky is clear, dark, and calm.

During early evening this week, Titan will start from a position off to Saturn’s upper left (or celestial east) tonight (Sunday), pass just below (celestial south of) Saturn from Thursday to Friday, and then extend to Saturn’s lower right (or celestial west) by next Sunday night. (Remember that your telescope will probably flip the view around.) The rest of the moons will be tiny specks in a line near the rings. Earth’s perspective of the Saturn system will also cause Saturn’s moons and their small black shadows to frequently cross its disk – but you’ll need a very high quality telescope to watch those.

Distant, blue Neptune can be seen in a backyard telescope when the moon isn’t too bright nor too close to it (as it will be next Sunday night). It follows Saturn across the sky every night, just shy of 1.5 fist widths to the upper left (or celestial ENE) of Saturn and a palm’s width to the lower left of the circle of faint stars that forms Pisces’ western fish. Use binoculars to find the upright, tilted rectangle formed by the medium-bright stars 27, 29, 30, and 33 Piscium. Neptune will be the bluish, dull “star” sitting about two finger widths to the upper right (or 2° to the celestial north) of that box.

As Venus is setting in the west, the brilliant, white planet Jupiter will be climbing in the east. From now until early February, Jupiter will be moving west between the horn stars of Taurus (the Bull), Elnath and Zeta Tauri. Those stars will shine to Jupiter’s upper left and lower left, respectively. Jupiter’s westerly motion will also carry it steadily closer to Taurus’ brightest star, reddish Aldebaran, which marks the eye of the bull. This week, Jupiter and Aldebaran will be less than a fist’s diameter apart, and closing. The winter constellations will shine below Jupiter every day from late evening onward, and then become rotated to the planet’s left after midnight.

This is a big week for Jupiter! On Saturday night, it will reach opposition for 2024. At opposition, planets rise in the east at sunset and cross the sky all night long before setting in the west at sunrise. Jupiter will be at its minimum distance from Earth for this year of 611.8 million km or 34 light-minutes, boosting its brilliance to magnitude -2.8. If that night is cloudy, any other night close to that date will be as good.

Viewed in any size of telescope, the planet will display a generous, 48.2 arc-seconds-wide disk striped with brown dark belts and creamy light zones, which are aligned parallel to its equator. With a better grade of optics, Jupiter’s Great Red Spot, a cyclonic storm that has raged for hundreds of years, becomes visible for several hours when it crosses the planet every 2nd or 3rd night. For observers in the Americas, that GRS will cross Jupiter’s disk during early evening on Tuesday, Thursday and Saturday, and also towards midnight Eastern time on Monday and Wednesday night. If you have any coloured filters or nebula filters for your telescope, try enhancing the spot with them.

Any size of binoculars will show you Jupiter’s four Galilean moons named Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto lined up beside the planet. Those moons complete orbits of the planet every 1.7, 3.6, 7.2, and 16.7 days, respectively. If you see fewer than four moons, then one or more of them is crossing in front of or behind Jupiter, or hiding in Jupiter’s dark shadow – or two of the moons are very close together, or one moon is eclipsing or occulting another one.

From time to time, observers with good quality telescopes can watch the black shadows of the Galilean moons travel across Jupiter’s disk. In the Americas, Io’s little shadow will cross on Sunday, December 1 between 9 pm and 11:11 pm EST (or 02:00 to 03:11 GMT). Europa’s little shadow will cross on Thursday, December 5 between 10:12 pm and 12:44 am EST (or 03:12 to 05:44 GMT).

I skipped over Uranus since Jupiter is so much easier to see – but that distant ice giant planet is observable all night long, if you know where to look. This month Uranus is located about a palm’s width to the right (or celestial southwest) of the bright little Pleiades star cluster in Taurus (the Bull). If you use your binoculars to find the medium-bright stars named Botein and Epsilon Arietis, Uranus will be the dull-looking blue-green “star” located several finger widths below (or southeast of) them. To get you in the vicinity of Uranus, look for the bright star Menkar shining 2.2 fist diameters off to the right of the Pleiades and down a little. Uranus will be a quarter of the way along the line joining the bottom star of the Pleiades to Menkar.

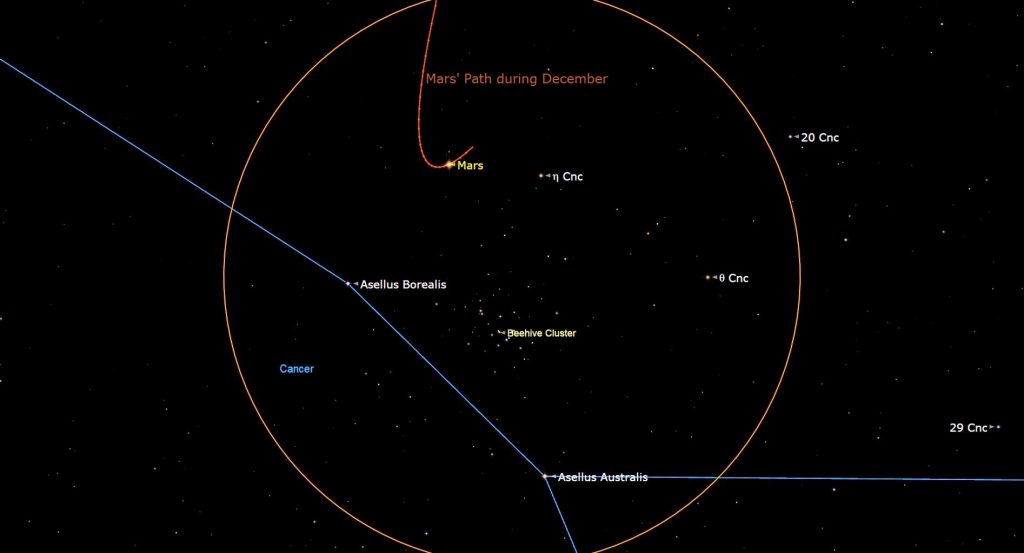

Last up – literally – will be Mars! The famous red planet will clear the trees in the east by 10 pm local time. It will cross the sky all night long, chasing Jupiter and Uranus, and end up halfway up the southwestern sky before dawn. Mars is growing bigger and brighter every day as the distance between our two planets diminishes. This week it will be about 117 million km away. In a telescope this week, the red planet will display a small, reddish disk. We’ll start seeing surface details as Mars gets closer to Earth every day until its opposition night on January 15-16.

Mars will be shining more than a fist’s diameter below the bright star Pollux, the lower of the “twin” stars of Gemini, but the planet is actually in central Cancer (the Crab). On Saturday, Mars’ easterly orbital motion will slow to a stop in order for it to begin a westerly retrograde loop that will last through its mid-January opposition and into late February. This week, the planet will be shining just above (or celestial north of) the large open star cluster in Cancer known as the Beehive, Praesepe, and Messier 44. Mars and the stellar “bees”, which will be scattered across an area more than twice the size of a full moon, will fit into the field of view in binoculars for several weeks. The planet will be closest to the cluster from now until Friday and then it will be increasingly farther above the cluster in December.

Public Astronomy-Themed Events

Every Monday evening, York University’s Allan I. Carswell Observatory runs an online star party – broadcasting views from four telescopes/cameras, answering viewer questions, and taking requests! Details are here. They host in-person viewing on the first clear Wednesday night each month. Other Wednesdays they stream views online via the observatory YouTube channel. Details are here.

On Wednesday evening, December 4 at 7:30 pm EDT, the RASC Toronto Centre will host their free, public Recreational Astronomy Night Meeting, at the Petrie Science building at York University and also live streamed at https://www.youtube.com/rasctoronto/live. Talks will include The Sky This Month, discovering exoplanets, and more. Details are here.

On Thursday, December 5, starting at 7 pm EDT, U of T’s AstroTour at McLennan Physical Laboratories, 60 St George St., Toronto, will present a free public lecture by U of T Graduate Student Tanisha Ghosal. Her talk will be What our Sun Can Teach Us About the Plasma-Filled Universe. The talk will be followed by astronomy demos and telescope tours (weather permitting). Details are at https://uoft.me/astrotours.

Keep your eyes on the skies! I love getting questions and requests. Send me some!