The Missing Moon Brings More Meteors and Comet Views, Mars Nears Uranus, and Summer Triangle Treats the Animals!

The Dumbbell Nebula, imaged by Steve McKinney, is a large planetary nebula in Vulpecula (the Fox). It’s visible (without colour) in a backyard telescope. Planetary nebulae are the corpses of stars with mass similar to our sun. This one resembles and apple core! This image covers a patch of sky about as wide as a full moon.

Hello, late-July Stargazers!

Here are your Astronomy Skylights for the week of July 24th, 2022 by Chris Vaughan. Feel free to pass this along to your friends and send me your comments, questions, and suggested topics. You can also follow me on Twitter as @astrogeoguy! Unless otherwise noted, all times are expressed in Eastern Time. To subscribe to these emails please click this MailChimp link.

If you’d like me to bring my Digital Starlab portable inflatable planetarium to your school or other daytime or evening event, or deliver a session online, contact me through AstroGeo.ca, and we’ll tour the Universe, or the Earth’s interior, together! My terrific new book with John A. Read entitled 110 Things to See With a Telescope is a guide to viewing the deep sky objects in the Messier List – for both beginners and seasoned astronomers. DM me to order a signed copy!

The moon will be missing from evening skies worldwide until it returns as a slender crescent in the western sky after sunset, near Mercury, at week’s end. That will leave skies dark for yet more views of evening comet c/2021 K2 (Panstarrs), for Delta Aquariids meteors, and for exploring the sights to see around the Summer Triangle. Bright planets appear by midnight. Read on for your Skylights!

Southern Delta Aquariids Meteor Shower

The Southern Delta Aquariids meteor shower runs annually from July 21 to August 23. It will peak overnight on Friday-Saturday, July 29-30, but is especially active for a week surrounding that date, so you can keep an eye out for shooting stars all week long. The prolific Perseids meteor shower, which runs annually between July 17 and August 26, has begun, too! That shower will peak on August 12.

Meteor showers are events that re-occur on the same dates every year when the Earth’s orbit carries us through zones of small particles left behind by multiple passes of periodic comets. (The analogy would be the material tossed out of a dump truck as it rattles along. The roadway gets pretty dirty if the truck drives the same route a number of times!) Over time, the dust-sized and sand-sized (and sometimes larger) particles accumulate and spread out into a ring-shaped cloud in interplanetary space.

When the Earth plows through the cloud, the particles are caught by our gravity and burn up as they fall through our atmosphere at speeds on the order of 200,000 km/hr. The friction caused by grains moving that quickly through the air generates intense heat that ionizes the air – producing the long glowing trails we see. The duration of a meteor shower depends on the width of the particle cloud – and therefore how long Earth takes to pass through it. The shower’s intensity depends on the type of particles in it, and on whether we pass through the densest portion, or merely skirt the edges. Not surprisingly, a shower’s performance can vary from year to year.

The nickname for meteors is “shooting stars” or “falling stars”, but they bear no physical connection to the distant stars. The action is taking place 100-200 km over your head and within Earth’s blanket of atmosphere. All of your favourite constellations will look the same as ever at the end of the shower!

While visible anywhere in the night sky, meteors will appear to be travelling away from a location in the sky called the radiant. The Southern Delta Aquariids meteor shower radiant is located in Aquarius (the Water-Bearer) – hence the name. This year, the bright planet Saturn will be shining a fist’s diameter to the right (celestial west) of the radiant – making a nice signpost. The Southern Delta Aquariids radiant will rise above the southeastern horizon in late evening – and climb a third of the way up the southern sky around 3 am local time. Meteor showers are busiest in the hours before dawn because that’s the time when the sky overhead is plowing directly into the oncoming debris field, like bugs splatting on a moving car’s windshield. When the radiant constellation is highest, more of the sky is available for meteors. When it’s low, half of the meteors are hidden below the horizon.

This shower, produced by debris dropped from periodic Comet 96P/Machholz, commonly generates 15-20 meteors per hour at the peak. It is best enjoyed from the southern tropics, where the shower’s radiant climbs higher in the sky. Meteors showers can be spoiled by moonlight. Fortunately, the moon will follow the sun down after dusk on this year’s peak nights, leaving the overnight sky nice and dark around the world.

To see the most meteors during any shower, try to find a safe, ideally rural, viewing location with as much open sky as possible. If you can hide bright lights behind a building or tree, that will help. You can start watching as soon as the sky becomes dark. That’s also a good time to catch the rarer, very long meteors produced by particles skipping across the Earth’s upper atmosphere. Don’t worry about watching the radiant. Meteors in that part of the sky will be heading directly towards you and will have very short trails. Instead, try to track the meteors’ paths backwards to find their radiant.

Bring a blanket for warmth and a chaise to avoid neck strain, plus snacks and drinks. Try to keep watching the sky even while chatting with friends or family – they’ll understand. Call out when you see one; a bit of friendly competition is fun!

Don’t look at your phone or tablet – its bright screen will spoil your dark adaptation. If you must use it, turn the brightness down, or cover the screen with red film. Disabling app notifications will reduce the chances of unexpected bright light, too. And remember that the narrow fields of view that binoculars and telescopes deliver will not help you see meteors. Good luck!

The Moon

The moon will be completely absent from the evening sky worldwide until the coming weekend – so skywatchers will enjoy especially dark skies this week.

Overnight tonight (Sunday) the waning moon’s pretty crescent will rise between the horn-tip stars of Taurus (the Bull) at about 3 am local time. The bright winter-time stars Capella and Aldebaran will bracket the moon to the upper left and right, respectively. Set the alarm for about 5 am on Monday morning to see the bright planet Venus gleaming below the moon before sunrise hides it. On Tuesday morning, the even slimmer moon will descend to shine a few finger widths above (or 4° to the celestial north of) Venus – close enough to share the view in binoculars. Both objects will be among the stars of Gemini (the Twins). On Wednesday morning the old moon might be glimpsed in the brightening sky a fist’s diameter to the lower left of Venus.

You probably feel that my extra references to the celestial angle between two objects disrupt the flow of the Skylights text. I include them because up-down-left-right descriptions will be completely wrong for Skylights readers in the Southern Hemisphere. Forgive me.

On Thursday at 1:55 pm EDT or 10:55 am PDT (17:55 Greenwich Mean Time), the moon will officially reach its new moon phase. At that time our natural satellite will be located in Cancer (the Crab), 4.5 degrees above (north of) the sun. While new, the moon is travelling between Earth and the sun. Since sunlight can only illuminate the far side of the moon, and the moon is in the same region of the sky as the sun, it becomes completely hidden from view from anywhere on Earth for about a day.

It will be theoretically possible to glimpse the young crescent moon above the west-northwestern horizon right after sunset on Thursday. If you have a cloud-free, unobstructed horizon, give it a try – but do not use binoculars to look for it until the sun has completely set. The planet Mercury will be located a fist’s diameter to the moon’s left.

On Friday, the moon will have travelled far enough above the sun to give you a real chance to see its crescent after sunset. At that time, Mercury’s dot will be just two finger widths below (or 2.5° to the celestial south of) the moon. On Saturday, the moon will shine prettily in the west – and a fist’s diameter to Mercury’s upper left – while the sky darkens after sunset. Sunday will be easy, too. On both evenings, the surrounding stars of Leo (the Lion) might appear as the moon sets.

The Planets

Summer planet-gazing keeps on getting better. Mercury is slowly climbing in the post-sunset glare in the west, and two bright, late-night planets are becoming more observable.

The steady slide of Earth around the sun causes the stars to rise four minutes earlier each night. That results in fresh constellations joining the eastern sky with each passing month, while those that have completed their time in the spotlight sink into the sunset. The same is more or less true for the planets. The ones orbiting far from the sun barely move compared to the stars around them – so they, too, rise about four minutes earlier each night. Saturn began to rise before midnight around June 21. Now, its medium-bright, yellowish dot is already shining in the southeastern sky by 10:30 pm local time. It’ll have climbed high enough for reasonable telescope views an hour later, and that timing will shift half an hour earlier with each passing week! We’ll be able to enjoy Saturn until early January.

This year Saturn will be shining among the modest stars of eastern Capricornus (the Sea-Goat). Since Saturn is now moving slowly westward in a retrograde loop that will last until late October, you can watch it shift more to the right (celestial west) above Capricornus’ easterly tail star Deneb Algedi over the next few weeks. Retrograde loops occur when Earth, on a faster orbit closer to the sun, passes the distant planets “on the inside track”, making them appear to move backwards across the stars. You can view the ringed planet all night long – but the clearest views will come during the wee hours, when it will be highest in the south, and seen through less of Earth’s distorting atmosphere. Any size of telescope will show you Saturn’s globe extending above and below its tilted rings, and a handful of its moons arrayed around the planet.

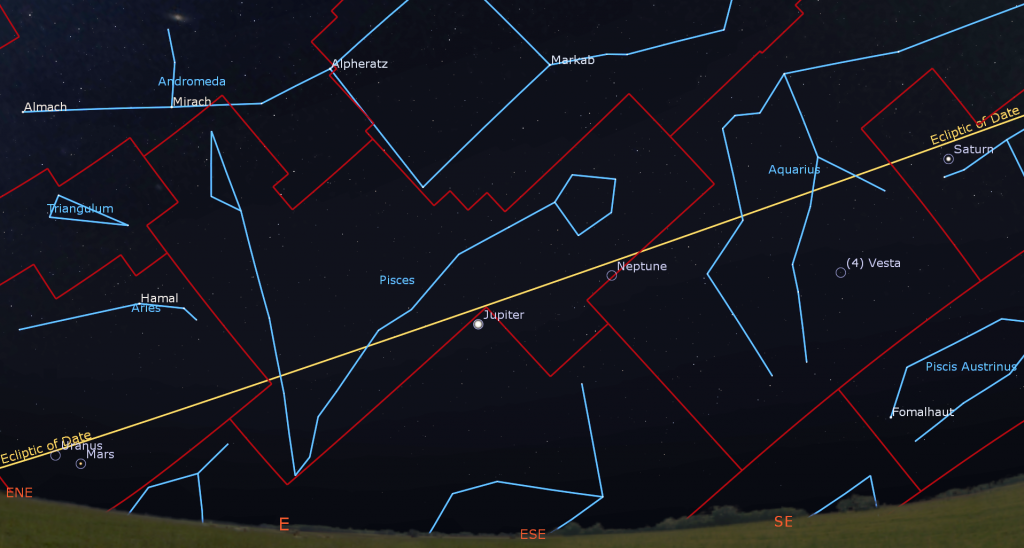

The main belt asteroid designated (4) Vesta is currently positioned 1.4 fist diameters to Saturn’s lower left (or 14° to its celestial east). Vesta’s own retrograde loop will reduce its spacing from Saturn in the coming weeks. Its magnitude 6.2 speck will be observable in binoculars and small telescopes, especially between about 1 and 4 am local time (i.e., while it’s highest in a dark sky). Look for Vesta several finger widths to the upper right (or 3 degrees to the celestial northwest) of the medium-bright star Skat (aka Delta Aquarii), and two finger widths to the right of the fainter star Tau Aquarii.

The planet party levels up when the very bright, white dot of Jupiter joins Saturn around midnight. This year Jupiter will occupy the northwestern corner of Cetus (the Whale), shining about 4.4 fist diameters to the lower left (or 44° to the celestial northeast) of Saturn. On Friday, the eastward prograde motion of Jupiter through those background stars will slow to a stop. After that, Jupiter will commence a westward retrograde loop that will last until the end of November.

Jupiter will climb high enough to look good in a telescope from 1 am local time onward. Just before sunrise, the planet will reach halfway up the southeastern sky. Good binoculars will show Jupiter’s disk flanked by its row of four Galilean moons, which form a different arrangement each day. Any size of telescope will show dark bands running parallel to Jupiter’s equator. For observers in the Americas, the Great Red Spot will cross Jupiter in the wee hours of Monday, Tuesday, Thursday, and Saturday morning. No good shadow transits this week.

The faint blue speck of Neptune will be sharing the sky near Jupiter. The magnitude 7.8 planet will be positioned 1.3 fist diameters to Jupiter’s right, and a finger’s width to the upper right (or 1° to the celestial west) of a small star named 20 Piscium, which sits on the line joining Jupiter to Saturn.

The rest of the planets can be enjoyed between midnight and sunrise. Medium-bright, reddish Mars will clear the eastern rooftops after about 2 am local time. Mars will shine about 3.5 fist diameters to the lower left of Jupiter on Monday, but its distance from Jupiter will increase a little bit every morning. In a telescope, Mars will show a tiny, 85%-illuminated disk. The red planet will brighten and grow larger gradually as Earth’s faster orbit draws us closer to it over the coming months.

Mars’ relatively rapid eastward orbital motion will cause it to pass slowpoke Uranus after the coming weekend. Magnitude 5.8 Uranus is easily visible in binoculars and backyard telescopes this week, especially between 3 am and dawn. After the two planets rise on Monday morning, Mars will be located less than a binoculars’ field of view to the right (or 5° to the celestial west-southwest) of Uranus. Next Sunday morning, Mars will shine only a thumb’s width to the lower right of Uranus – close enough to share the eyepiece in a backyard telescope (although the telescope will likely flip and/or mirror their arrangement). When Mars isn’t nearby, the brightest guidepost to Uranus is the medium-bright star named Botein (or Delta Arietis). Uranus is several finger widths to its right (or 4° to the celestial southwest).

Extremely bright Venus will clear the east-northeastern treetops by 5 am local time every morning – but it won’t climb very high by sunrise – unless you live in the tropics. Venus will exhibit a waxing, nearly-round shape when viewed in a telescope or in good binoculars. The planet is slowly shifting closer to the sun. The lengthy string of planets from Venus to Saturn roughly traces out the ecliptic and the plane of our solar system.

Faint Comet Update

This week’s absent moon will allow more views of comet C/2017 K2 (PanSTARRS). The comet is still near to its peak brightness of about magnitude 8.5, which is within reach of most telescopes. It passed its closest point to the sun (perihelion) and to the Earth (perigee) last week. From now on it will gradually fade in brightness as its climbs out of the plane of the solar system and increasingly farther from us and the sun. You can play with an online 3D model of the comet’s orbit at https://theskylive.com/3dsolarsystem?obj=c2017k2

The comet is observable from full darkness until well beyond midnight. It will be moving through the stars of the Dalek-shaped constellation of Ophiuchus (the Serpent-Bearer), which sits about halfway up the southern sky in late evening. During this week, the comet will be travelling downwards to the right (or celestial southwestward) near the bright star Saik, which marks the mid-point of the bottom edge of Ophiuchus (the Serpent-Bearer). Tonight (Sunday) the comet will be positioned two finger widths above (or 2.7° to the celestial north of) Saik. On Wednesday and Thursday night, the comet will pass a thumb’s width to the star’s upper right (or celestial northwest) – close enough to share the view in a backyard telescope. (Your telescope will like flip and/or mirror the view.) Next Sunday night, Comet c/2017 K2 will sit two finger widths to Saik’s right.

A Summer Triangle Tour

When you are outside on the next clear night, be sure to look for the three bright and beautiful blue-white stars of the Summer Triangle asterism, which shines high in the eastern sky in late July and early August. Once you have it identified, you can find some treasures within it, and follow its progress across the night sky until it finally disappears in late fall.

Find an open area and face east. The very bright star Vega will be almost straight over your head. It’s the fifth brightest star in the entire night sky, and one of the first stars to appear after dusk. Now look for the other two corners of the triangle. Altair, not as bright as Vega, sits about 3.5 outstretched fist diameters to the lower right of it (or 34° to the celestial SSE). The third star, Deneb, is about 2.5 fist diameters to the lower left of Vega (or 24° to the celestial east), and is higher up than Altair. It’s a very big triangle!

Can you see the four fainter stars forming a small, upright parallelogram just below Vega? That shape is about a thumb’s width wide and a few finger widths tall. This box is the body of the musical harp that makes up the constellation of Lyra (the Lyre). Vega marks the top of the instrument’s neck. Vega’s visual magnitude, or brightness, is the zero reference point for the scale we use to define stars’ brightness values. Objects brighter than Vega have values lower than zero, and vice versa. Antares, the bright, reddish star sitting over the southern horizon in Scorpius (the Scorpion), has a value of about 1.0, making it 2.5 times dimmer than Vega. (It’s a logarithmic scale.)

Vega also forms a little triangle with two other dim stars, each about a finger’s width apart. The star to Vega’s upper left is named Epsilon Lyrae, also known as the Double Double. Can you tell it’s actually two stars crammed tightly together? Try using binoculars. When magnified in a telescope, each of those stars splits again!

Deneb marks the tail of great bird Cygnus (the Swan). Look for a modest star sitting about two fist diameters to the right (or 22° to the celestial southwest) of Deneb. That’s Albireo, a colourful double star that marks the swan’s head. (I like to think of Albireo as the centre of Doc Brown’s flux capacitor from Back to the Future. The summer triangle’s stars are that gadget’s corners!) Albireo was given only one name before telescopes revealed that it was composed of two stars!

A widely spaced string of medium-bright stars aligned up-down traces out the swan’s wings. (Look closer to Deneb than Albireo for them – swans have long necks!) The brighter star in the middle of the wing span is Sadr, marking the swan’s belly. If you are in a dark location, you should also be able to see that the Milky Way runs right through Cygnus, as if she is about to land for a swim on that celestial river! Use your binoculars to explore the swan from head to tail. You’re bound to find little clumps of stars and glowing gas!

The most southerly of the triangle’s corners is marked by Altair – the head of the great eagle Aquila. In fact, its name translates from “the flying eagle”. At only 16.8 light-years distance, Altair is one of the nearest bright stars – so close that its surface has been imaged! The star also seems to be spinning 100 times faster than our sun, probably generating an equatorial bulge. Like Cygnus, the Aquila the eagle is oriented with its wingtips up-down. The tail bends to the lower right. Two little stars named Tarazed (above, or north) and Alshain (below, or south) sit on either side of Altair, like a balance. As a matter of fact, those two little stars’ names derive from an old-fashioned scale balance. In the Chinese folk tale of The Cowherd and the Weaver Girl, Tarazed and Alshain are children of the cowherd Niú láng 牛郎 (the star Altair), and the princess Zhīnü 织女 (the star Vega).

Grab your binoculars and look about midway between Vega and Altair for a little grouping of stars called the Coathangar. It’s composed of a rod made by a line of six stars spanning a thumb’s width in length, plus a hook made up of four stars. (Hint: For North American observers, it’s oriented with the hook downwards to the right.) Its fancier names include Brocchi’s Cluster, Al Sufi’s Cluster, and Collinder 399. A Closer look will show that most of the stars are hot, white A- and B-class stars. The other three are cooler, reddish K- and M-class stars.

Finally, have a look for two little constellations in the area. Sagitta (the Arrow) comprises five faint stars, aligned left-right, located midway between Altair and Albireo. The three stars on its right (western) end form the feathers. Just below the middle of the arrow’s span is a fairly bright globular star cluster named Messier 71 or the Angelfish Cluster. Under a dark sky, binoculars should show it as a small, faint, fuzzy star. In a backyard telescope it will resemble a mound of sugar sprinkled on black velvet.

Below Sagitta, and about 1.3 fist diameters to the left (or 13° to the celestial northeast) of Altair is cute little Delphinus (the Dolphin). Four stars form a diamond-shaped body and another star to the lower right of that makes the tail! The proper names for Delphinus’ two brightest stars are Sualocin and Rotanev, which are the Latinized form of the English-translated name of Italian astronomer Niccolò Cacciatore, i.e., Nicolaus Venator . Cacciatore wrote them in a star catalog in 1814 (as a joke, perhaps?), and they snuck through and remained in use!

There’s one more small constellation inside the summer triangle, but its dim stars make it difficult to see from the city. It’s called Vulpecula (the Fox). It is made up of only two magnitude 4.5 stars, and is located a palm’s width above (north of) Sagitta, near Albireo. One of Velpecula’s claims to fame, however, is the spectacular planetary nebula known as the Dumbbell, also known as Messier 27 and NGC 6853. From a dark location aim your telescope just two finger widths above (or 3° to the celestial north-northwest) of Sagitta’s arrow tip and look for a small, faintly glowing cloud of gas that resembles an apple core.

Two birds, a dolphin, and a fox! Keep a look out for the lizard Lacerta just to the east of these, and the little foal Equuleus sitting below Delphinus! Enjoy your tour of the triangle and visit to this celestial zoo!

Viewing the JWST Objects

Of the first five images released from the James Webb Space Telescope, two of the objects are observable from mid-northern latitudes by amateur astronomers with telescopes on July evenings! I described them here.

Touring the Dark Southern Sky

If you missed my short tour of the stars and deep sky treats visible with unaided eyes and binoculars in the Milky Way in mid-July, I posted it here. This week will also be terrific for viewing those sights.

Public Astro-Themed Events

Every Monday evening, York University’s Allan I. Carswell Observatory runs an online star party – broadcasting views from four telescopes/cameras, answering viewer questions, and taking requests! Details are here. They host in-person viewing on the first clear Wednesday night each month. Other Wednesdays they stream views online via the observatory YouTube channel. Details are here.

My free, family-friendly Insider’s Guide to the Galaxy webcasts with Samantha Jewett of RASC National returns on Tuesday, August 16 at 3:30 pm EDT, when we’ll do a summer planet preview! Plus, we’ll continue with our Messier Objects observing certificate program. You can find more details and the schedule of future sessions here.

Don’t forget to take advantage of the astronomy-themed YouTube videos posted by RASC Toronto Centre and RASC Canada.

Keep looking up, and enjoy the sky when you do. I love questions and requests. Send me some!