The Full Egg Moon Produces Passover and Easter, Major Venus and Mercury and Meagre Mars Shine in Evening, and Bright Stars Make Patterns!

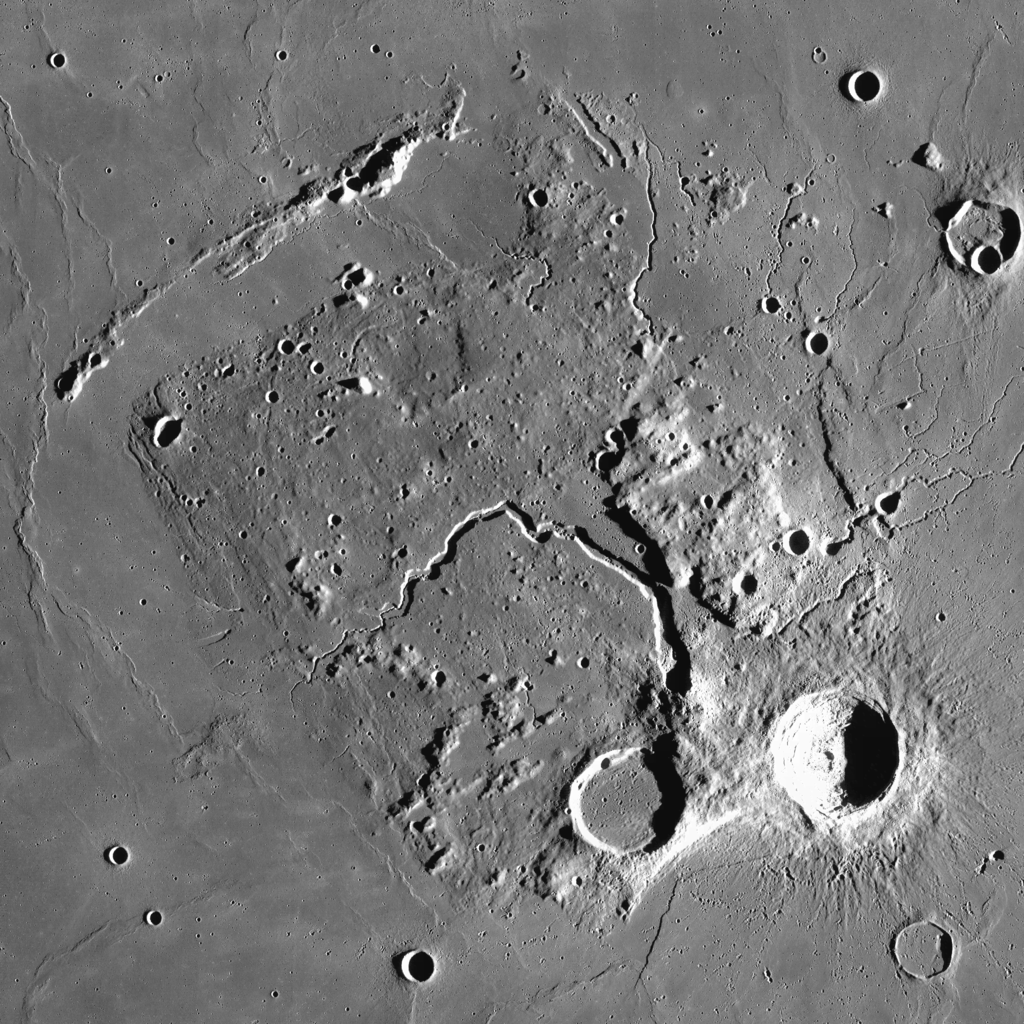

This image taken by the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter shows the fascinating Aristarchus Plateau. The crater Aristarchus at lower right is very prominent, and can be seen even with unaided eyes as a very bright patch. To its left is the similar-sized, but darker crater Herodotus. Vallis Schröteri, the largest sinuous rille on the moon, starts at a broad section near Herodotus, called the Cobra’s Head, and winds to the north, tapering along the way. All of those features sit within the elevated, rough-surfaced, diamond-shaped plateau.

Hello, April Stargazers!

Here are your Astronomy Skylights for the week of April 2nd, 2023 by Chris Vaughan. Feel free to pass this along to your friends and send me your comments, questions, and suggested topics. You can also follow me on Twitter as @astrogeoguy! Unless otherwise noted, all times are expressed in Eastern Time. To subscribe to these emails please click this MailChimp link.

If you’d like me to bring my Digital Starlab portable inflatable planetarium to your school or other daytime or evening event, or deliver a session online, contact me through AstroGeo.ca, and we’ll tour the Universe, or the Earth’s interior, together! My terrific book with John A. Read entitled 110 Things to See With a Telescope is a guide to viewing the deep sky objects in the Messier List – for both beginners and seasoned astronomers. DM me to order a signed copy!

The light of the moon will dominate the night sky worldwide this week as it waxes through full, so I highlight the moon’s influence on Easter and Pesach and some of the lunar features to view in binoculars or a backyard telescope. The inner planets will shine brightly over the western horizon in early evening, with fainter Uranus and Mars near them. Read on for your Skylights!

Easter, Passover, and the Full Moon

The moon will officially reach its full phase at 12:34 am EDT or 04:34 Greenwich Mean Time on Thursday, April 6. April’s full moon always shines in or near the stars of Virgo (the Maiden) or Libra (the Scales). Full moons are, by definition, opposite to the sun in the sky, so they always rise in the east as the sun sets, and set in the west at sunrise. But lunar phases occur independently of Earth’s rotation. The moon will look full from Wednesday evening to Thursday morning in the Americas – but only observers at longitudes around 18° E (central Europe and Africa) will see this one rising at sunset.

Every culture around the world has developed its own set of stories for the moon, and every month’s full moon now has one or more names. The indigenous Ojibwe groups of the Great Lakes region call the April full moon Iskigamizige-giizis “Maple Sap Boiling Moon” or Namebine-giizis, the “Sucker Moon”. For them it signifies a time to learn cleansing and healing ways. The Cree of North America call it Niskipisim, the “the Goose Moon” – the time when the geese return with spring. For the Mi’kmaw people of Eastern Canada, this is Penatmuiku’s, the Birds Laying Eggs Time moon. The Cherokee call it Kawonuhi, the “the Flower Moon”, when the plants bloom. For Europeans, it is commonly called the Pink Moon, Sprouting Grass Moon, Egg Moon, or Fish Moon. All of these terms reflect the changes in the natural environment at this time of year. It seems that “pink” refers to the phlox flowers that bloom first during spring in eastern forests – and NOT to the way the moon will appear!

Greetings to those who observe Easter and Passover! Easter Sunday and Pesach (Passover) have an astronomical connection to the full moon, with the Jewish Passover pre-dating the Christian Easter. Some believe that a full moon allowed for safer travelling by religious pilgrims of the time.

In 325 CE the Council of Nicaea determined that the moveable feast of Easter should be observed on the Sunday following the first full moon that occurs after the vernal equinox, officially known as the Paschal Full Moon. The council fixed the equinox at March 21, but the astronomical timing of the equinox actually varies a little bit, and even occurs a full day early on leap years. This year, the equinox occurred on March 20 at 5:24 pm EDT, so the coming weekend will contain Good Friday and Holy or Easter Sunday. The name “paschal” is derived from “Pascha”, a transliteration of the Aramaic word meaning Passover.

The Paschal moon controls the timing of Easter and Passover in different ways. Passover or Pesach is celebrated from the 15th through the 22nd of the Hebrew month of Nissan in the Jewish lunar calendar. Nissan began on March 23, when the new moon could first be spotted in Israel, so Passover will commence at sundown on Wednesday, April 5 and end at nightfall on Thursday, April 13. Easter and Passover can occur as much as a month apart, with Easter always the later of the two. Lunar calendars drift from solar calendars because there are 12.3 lunar months in a 365.25 day solar year. To correct for that, an intercalary or leap-month is inserted about every three years. In years when the post-equinox full moon occurs early, Jewish religious leaders will delay Passover by inserting a second month of Adar, called Adar II, to ensure that spring-like weather conditions (warmer temperatures and flowers in bloom) have arrived in Israel. The earliest that Passover can occur in our Gregorian calendar is March 25, which will next happen in 2089.

The Moon

The moon will shine brightly in the night sky worldwide this week. Tonight (Sunday) it’s 90%-illuminated orb will rise in late afternoon and then gleam among the bold stars of Leo (the Lion) all night long. The moon will rise about 65 minutes later each night. It will wax fuller until Thursday’s full moon and then begin to wane. It will remain in Leo on Monday night, and then spend Tuesday to Thursday crossing the lengthy form of Virgo (the Maiden).

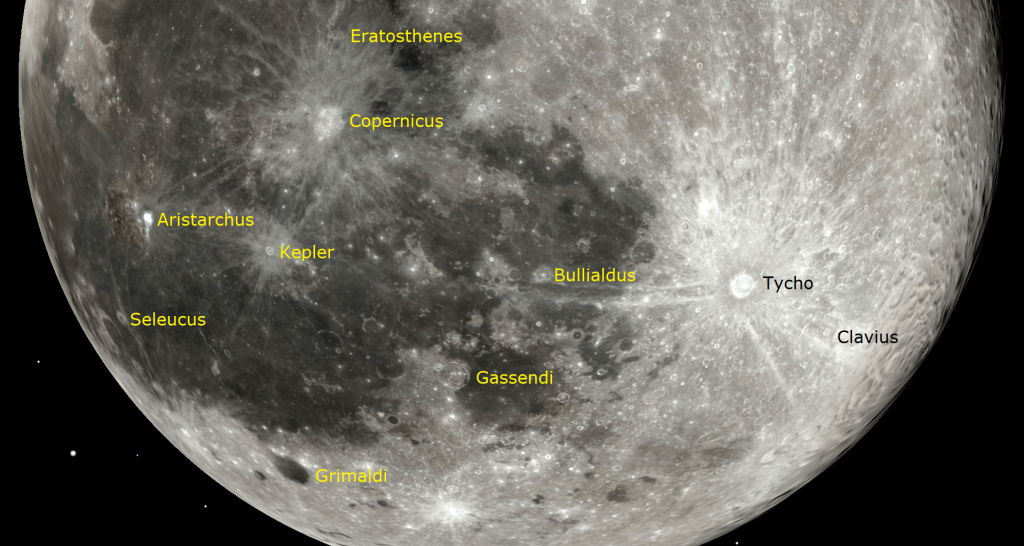

Grab your binoculars and look at the many ray systems sprayed across the moon’s Earth-facing hemisphere. The rays are straight lines composed of material that has been thrown radially outwards when the most recent craters were formed. The rays are particularly apparent when the moon is lit face-on, as it is around the full phase. Viewed in a telescope, major rays can be shown to be chains of small secondary impact craters excavated by the falling chunks of excavated rock (or ejecta), and by the scattered debris itself. Impacts on the light-coloured lunar highland rocks tended to spread white rays over the surrounding darker mare regions – but sometimes the inverse happens.

Some ray systems are enormous – spanning half the moon’s disk! The ray system of the crater Tycho is a fine example. Tycho is the very bright crater located in the south central part of the moon. Its rays are largely missing on the left-hand (lunar western) side, suggesting that its impactor, an asteroid 8 to 10 km in diameter, arrived from the west at an angle less than 45° above the lunar surface, throwing the ejecta in front of it, mainly to the east. In a telescope, you can see that Tycho is encircled by an asymmetrical dark blanket of rubble that is about as wide as the crater’s 85 km diameter. The dark colour is probably basaltic rock excavated from deep below the crust. Tycho and its rays are bright because it is a relatively young crater – only about 109 million years old. The dinosaurs were walking the Earth when the violent event happened! It’s too bad they couldn’t tell us what they saw!

The small crater Proclus is located at the lower left edge of Mare Crisium, the round grey basin near the moon’s upper right edge (northeast on the moon). Proclus’ bright rays only extend toward the right-hand side of the crater, mainly onto Crisium – again due to a very shallow impact trajectory. Many of the dark maria have the single streak of white ray across them. Can you trace it back to its origin?

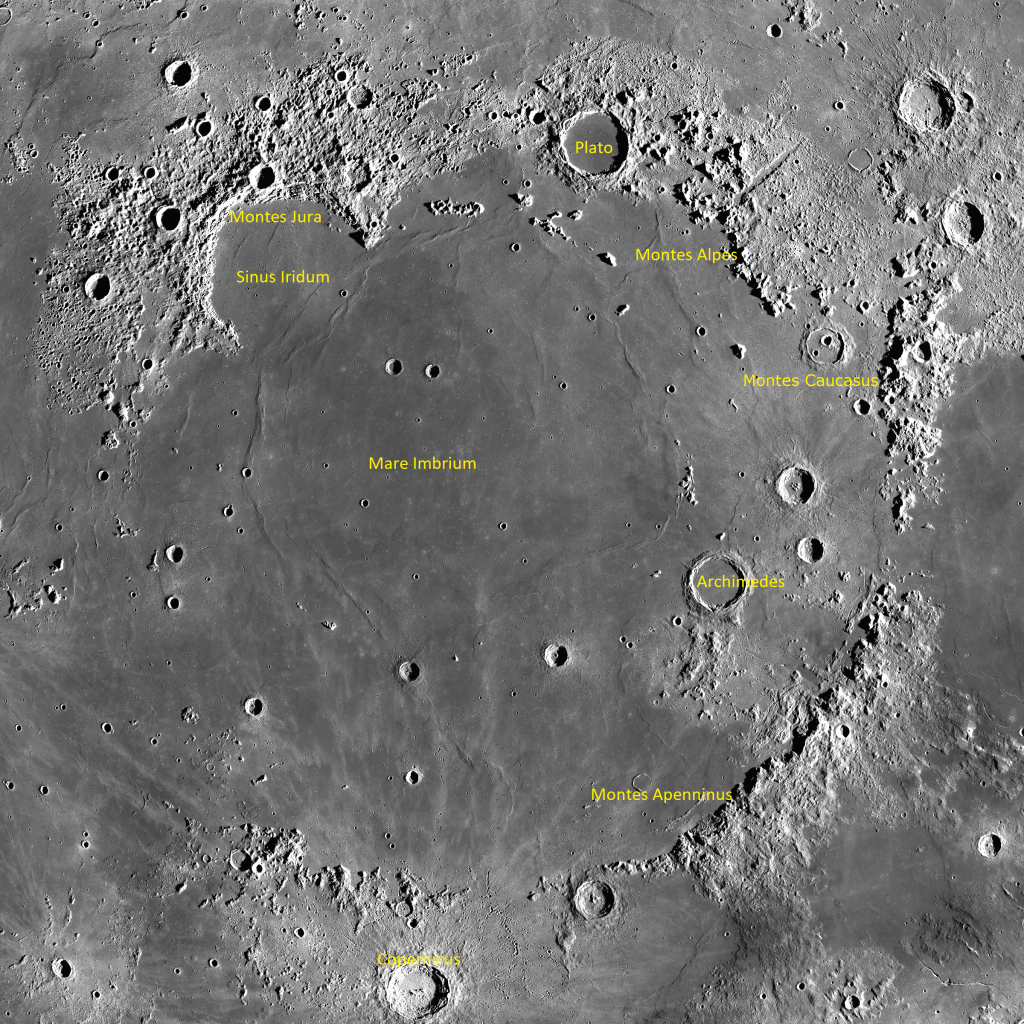

This week will also be ideal for exploring the western half of the moon. It is dominated by the large and irregular Oceanus Procellarum, the Ocean of Storms, and round Mare Imbrium, the Sea of Rains, which adjoins Procellarum to the upper right (or lunar northeast). Both are ancient basins that were excavated by huge impactors and later flooded with dark, iron-rich basalts that leaked through their floors from the moon’s interior. Since they formed after the time the moon was being heavily bombarded, the dark lunar maria are far less cratered than the bright highlands – but they are not featureless. Binoculars and telescope views reveal that the basalts vary in color and darkness due to their chemistry. When the lunar terminator is near a mare, slanted sunlight reveals the curved wrinkle ridges that ring each mare’s interior.

Mare Imbrium, the Sea of Rains, is the moon’s largest impact basin, measuring more than 1,145 km in diameter. It was formed during the late heavy bombardment period approximately 3.94 billion years ago. Binoculars and backyard telescope views of Mare Imbrium this week will reveal ejecta blankets around its major craters Aristillus, Autolycus, and Archimedes, the nearly-submerged ghost craters Cassini and Wallace, the isolated mountain ranges Recti, Teneriffe, and Spitzbergen, and its interior ring of subtle wrinkle ridges. The half-circle of Sinus Iridum, the Bay of Rainbows, interrupts Imbrium’s western edge.

Three prominent craters break up the expanse of Oceanus Procellarum. Large Copernicus is the easternmost. Its extensive, ragged ray system intermingles with the rays of the smaller crater Kepler to its southwest. The very bright crater Aristarchus positioned to the upper left (lunar northwest) of them occupies the southeastern corner of a diamond-shaped plateau that is one of the most colorful regions on the moon. NASA orbiters have detected high levels of radioactive radon there. Use a telescope and high magnification to view features like the large, sinuous rille named Vallis Schröteri. Its snake-like form begins between Aristarchus and next-door crater Herodotus and slithers across the plateau.

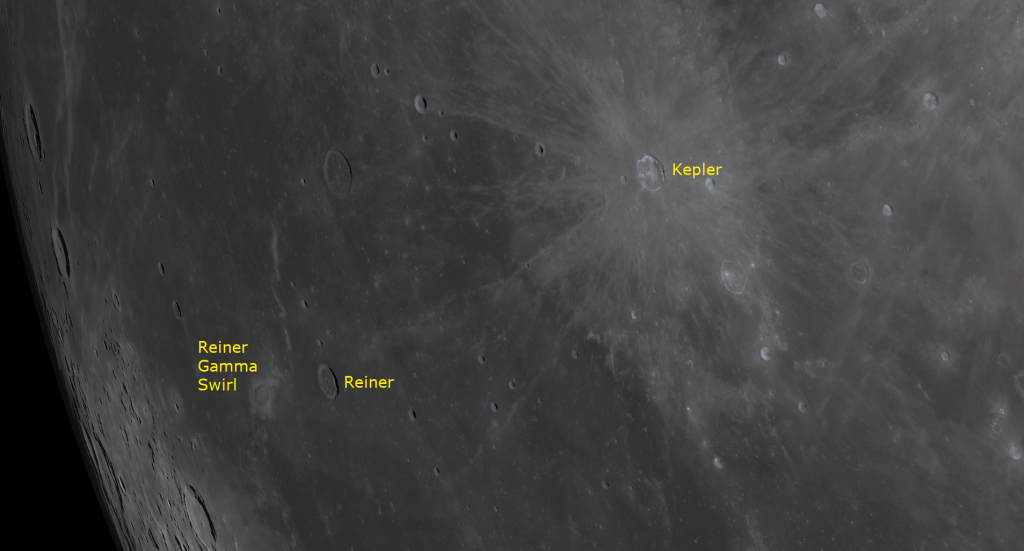

The Reiner Gamma Lunar Swirl is a small, high-albedo (i.e., light in colour) area located just inside the western edge of Procellarum, above (due north) of the dark, round crater Grimaldi and to the left (due west) of Kepler. It is best seen a night or two after the moon’s full phase. The easily seen 30 km diameter crater of Reiner is located a short hop to the right (east-southeast) of Reiner Gamma. The swirl is composed of ancient lunar basalt that has not been darkened by weathering, likely due to protection from cosmic rays by a strong localized magnetic field – the swirl has one of the strongest magnetic anomalies on the moon! At high magnification, its complex, fish-like shape is fascinating. Take a look!

On Friday and Saturday, the bright waning gibbous moon will shine starting in late evening among the stars of Libra (the Scales). When the moon rises over the southeastern horizon around midnight local time next Sunday night, it will be shining very close to the upper left (or celestial northeast) of bright reddish star Antares, the heart of Scorpius, the Scorpion. On the following mornings, the moon will linger low in the southwestern sky for a short time after sunrise.

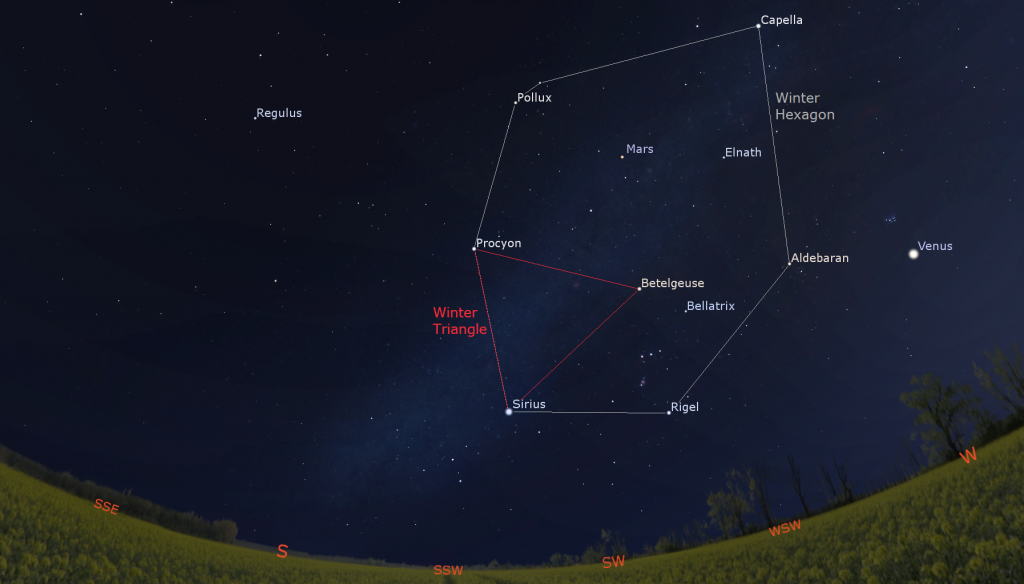

The Winter Triangle

The lower part of the south and western sky on early April evenings is dominated by the three stars of the Winter Triangle. The prominent asterism, visible even while the bright moon is shining, is anchored on the bottom by the magnitude -1.45 star Sirius or Alpha Canis Majoris, the brightest star in the night sky. Above Sirius (to the celestial NNE) shines the white, magnitude 0.34 star Procyon or Alpha Canis Minoris. The third, northwestern vertex is occupied by the reddish, magnitude 0.50 star Betelgeuse or Alpha Orionis. The Winter Triangle first appears in late evening during November. By the end of April it will be disappearing into the western post-sunset twilight.

The bright moon also won’t prevent us from seeing the big Winter Hexagon asterism. Also called the Winter Football, the Winter Circle, it is composed of the brightest stars in the constellations of Canis Major, Orion, Taurus, Auriga, Gemini, and Canis Minor – specifically Sirius, Rigel, Aldebaran, Capella, Castor & Pollux, and Procyon. I wrote more about it recently here.

Finally, if you are outside late at night this week, you can turn and face east to see the three bright stars of the Summer Triangle. Vega (Alpha Lyrae) will rise first at 9:30 pm local time, followed fifteen minutes later by Deneb (Alpha Cygni). Altair (Alpha Aquilae) will join them after 1:30 am. That delay is produced by Altair’s much more southerly declination. It’s 30° farther south than the other two stars. Scorpius (the Scorpion) and Ophiuchus (the Serpent Bearer) will be visible, too. Summer is just around the corner!

The Planets

The two inner planets Venus and Mercury will take centre stage in evening this week – though meagre Mars and unseen Uranus will accompany them. Last week’s media hype about a planetary alignment was way overblown. Planets are always “aligned” because they are strung along the imaginary arc across the sky that traces the plane of our solar system. Once or twice a year, a few of the bright planets will occupy the same sector of the sky. We like that these picturesque conjunctions and groupings get people outside to look up!

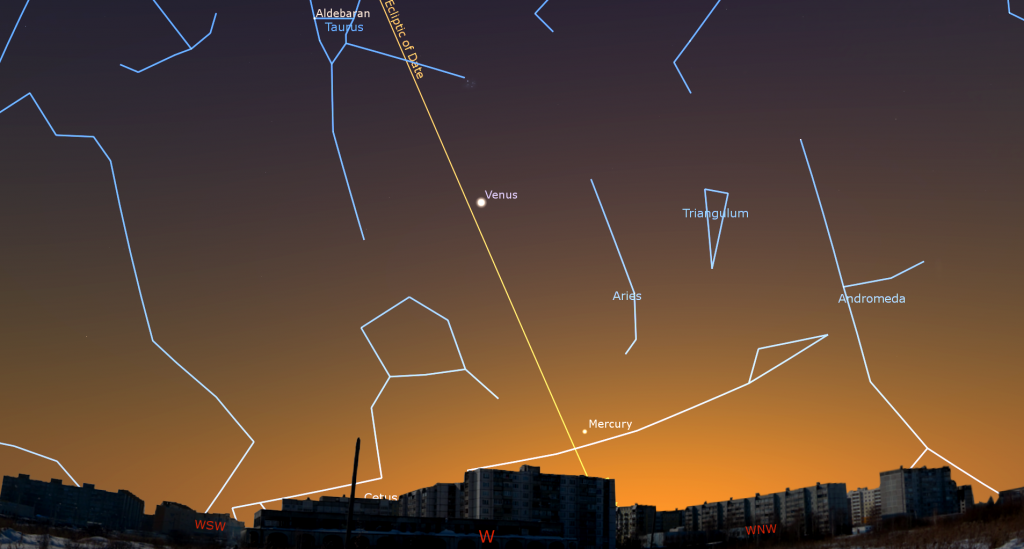

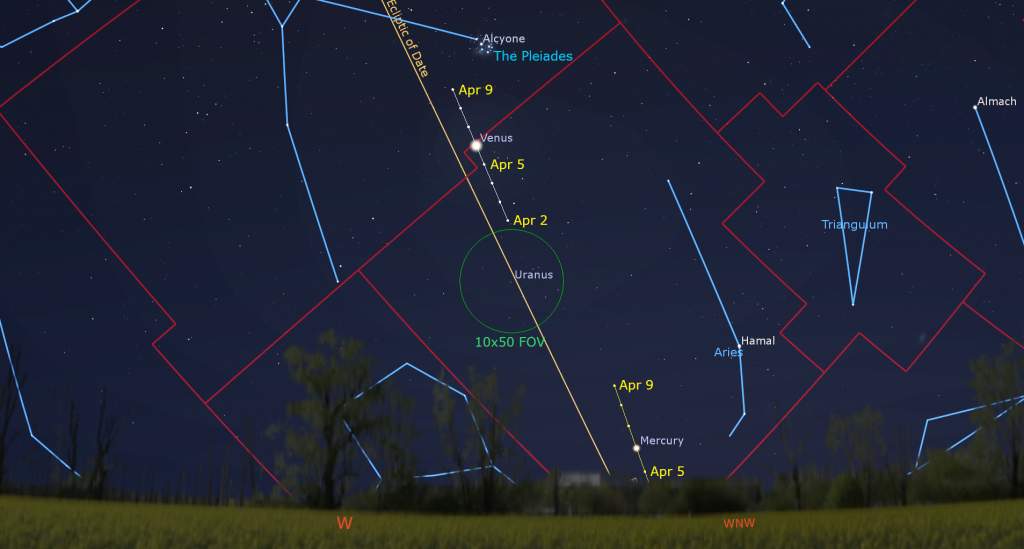

Extremely bright Venus will catch your eye on every clear night while it blazes away in the lower part of the western sky starting after sunset. Venus will brighten and climb higher each week. This week the planet will descend and set around 11 pm in your local time zone. Long before then the darkening sky will reveal the brightest stars of Aries (the Ram) and Taurus (the Bull) around it. Venus’s orbital motion has been carrying it towards the Pleiades star cluster in Taurus. Tonight (Sunday), that bright little clump will sit a fist’s diameter above (or 10° to the celestial east-northeast) of Venus. Starting on Thursday, the planet and the cluster will share the view in your binoculars. On next Sunday night, they’ll be only a few finger widths apart, and still closing.

Viewed in a telescope this week, Venus will display a gibbous 75%-illuminated disk that is waning daily. To see Venus’ rugby ball shape most clearly in a telescope, view the planet as soon as you can locate it through your optics, when it will be higher and shining through less intervening air.

Speedy Mercury has already swung far enough from the sun to be visible above the western horizon after sunset. This visit by Mercury will develop into its best evening appearance of the year for mid-Northern latitude observers. Mercury will reach maximum visibility next Tuesday – but there’s no need to wait. Once the sun has completely disappeared, you can begin to sweep the sky above the western horizon. The planet should be most visible after 8:15 pm – but it will only be a generous palm’s width high then. It’ll climb a little higher each night. A telescope will show a blurry view of its half-illuminated disk. Take care to avoid aiming a telescope or binoculars near the sun.

Last Thursday, Venus climbed past the planet Uranus. Now it is moving farther away from Uranus every day. For tonight (Sunday) and Monday Uranus’ magnitude 5.8 dot, which is visible in binoculars and backyard telescopes, will sit a few finger widths below (or celestial southwest of) Venus – close enough for them to share the field of view in binoculars. By the end of the week, Uranus will sit about midway between Venus and Mercury.

Mars’ easterly orbital motion beside the ecliptic continues to help it to delay its inevitable descent into the west until July. To see its motion for yourself, note its position with respect to the stars near it every few nights. Meanwhile, Mars continues to fade in brightness and become smaller in telescopes as Earth increases its distance from the red planet. After dusk tonight (Sunday), the red-tinted dot of Mars will appear in western Gemini (the Twins), about two-thirds of the way up the southwestern sky. That will be its best telescope viewing time – while it’s perched on high – but it will look tiny under any magnification. Mars will form a large red triangle above ruddy Betelgeuse at Orion’s shoulder and to the upper left of bright, reddish star Aldebaran, which marks the angry eye of Taurus (the Bull). Mars is noticeably fainter than those stars now. The planet will set during the wee hours of the night.

Over the coming weeks Saturn will gradually return to visibility above the eastern horizon before sunrise, especially if you live closer to the tropics.

Public Astro-Themed Events

Every Monday evening, York University’s Allan I. Carswell Observatory runs an online star party – broadcasting views from four telescopes/cameras (weather permitting), answering viewer questions, and taking requests! Details are here. They host in-person viewing on the first clear Wednesday night each month. On Wednesdays they stream views online via the observatory YouTube channel. Details are here.

On Wednesday evening, April 5 at 7:30 pm EDT, the RASC Toronto Centre will host their in-person monthly Recreational Astronomy Night Meeting in the Gemini East Room at the Ontario Science Centre. The meeting will also be live streamed at https://www.youtube.com/rasctoronto/live. Talks include The Sky This Month, red giant stars, and predicting aurorae. Details are here.

On Sunday afternoon, April 9 from 12:30 to 1 pm EDT, tune in for DDO Sunday Sungazing. Safely observe the sun with RASC, from the comfort of your home! During these family-friendly sessions, a DDO Astronomer will answer your questions about our closest star: the sun! Learn how the sun works and how it affects our home planet. Live-streamed views of the sun through small telescopes will be included, weather permitting. Only one registration per household is required. Deadline to register for this program is Wednesday, April 5, 2023 at 3 pm. Prior to the start of the program, registrants will be emailed the virtual program links. More information is here and the registration link is here.

My free, family-friendly Insider’s Guide to the Galaxy webcast with RASC National returns on Tuesday, April 11 at 3:30 pm EST. We’ll talk about the inner planets Mercury and Venus and how to see them. Then we’ll wrap up by highlighting our next batch of spring RASC Finest NGC objects. You can find more details and the schedule of future sessions here.

Keep looking up, and enjoy the sky when you do. I love questions and requests. Send me some!