Moon Maps, Full Flower Moon Floods Night with Light, and Planets Prefer Predawn!

Hello, Mid-May Stargazers!

Here are your Astronomy Skylights for the week of May 19th, 2024 by Chris Vaughan. Feel free to pass this along to your friends and send me your comments, questions, and suggested topics. You can also follow me on Twitter as @astrogeoguy! Unless otherwise noted, all times are expressed in Eastern Time. To subscribe to these emails please click this MailChimp link.

If you’d like me to bring my Digital Starlab portable inflatable planetarium to your school or other daytime or evening event in Simcoe, Grey, and Bruce Counties, or deliver a virtual session anywhere, contact me through AstroGeo.ca, and we’ll tour the Universe, or the Earth’s interior, together! My book with John A. Read entitled 110 Things to See With a Telescope is a guide to viewing the deep sky objects in the Messier List – for both beginners and seasoned astronomers. DM me to order a signed copy!

The bright moon will make stargazing tough this week until it wanes after its Full Flower phase on Thursday, so we highlight some things to see on the full moon and how folks have mapped it. The planets will all align in the east before sunrise, but only two of them are very visible. Read on for your Skylights!

The Moon

The bright moon will flood the evening sky with light until late this week as it waxes to full. On the coming weekend the moon will be rising late enough for us to see the stars.

Today (Sunday) the 88%-illuminated, waxing gibbous moon will rise in the late afternoon daylight. Once the sky darkens several hours later, the star Spica, the brightest one in Virgo (the Maiden), will be visible to the very bright moon’s lower right (or celestial southeast). Binoculars will better show the star against the moon’s glare. As the hours pass the moon’s continuous eastward orbital motion will be apparent as it changes its distance from Spica.

The moon will remain in Virgo on Monday, and then slide into next-door Libra (the Scales) for Tuesday and Wednesday. By mid-week the moon will be rising at dusk and setting in the west before dawn. If you don’t mind waiting for it to climb above the trees after about 10 pm, the western edge of the moon will reveal nice texture in binoculars and any small telescope.

From tonight until Wednesday, the pole-to-pole lunar terminator will migrate west on the moon, revealing more and more of the broad, dark expanse of Oceanus Procellarum, which spreads across much of the moon’s western Earth-facing hemisphere. That “Ocean of Storms” covers about 4 million square km, equal to about the western half of Canada. Early in the moon’s history, a large object smashed into the moon at high speed, excavating a shallow bowl, 3,000 km wide, in the moon’s still-cooling crust. Later, dark, iron-enriched magma leaked out of the interior of the moon and flooded that basin with the dark rock we see today.

The moon will officially reach its full phase on Thursday, May 23 at 9:53 am EDT, 6:53 am PDT, or 13:53 Greenwich Mean Time. The moon only appears full when it is opposite the sun in the sky, so full moons always rise in the east as the sun is setting, and set in the west at sunrise. The full moon will rise at sunset only for the longitudes near Kabul, Afghanistan and Karachi, Pakistan. In the Americas, the moon will appear to be full on Wednesday, but closer inspection will reveal a strip of shadow curving along the moon’s left limb. When the moon rises on Thursday evening, that strip of shadow will have transferred over to the moon’s right (or eastern) limb.

Full moons in May always shine in or near the zodiac constellations of Libra or Scorpius. The sun travels along the ecliptic. That circle more or less expresses the plane of our solar system across the sky and crosses through the zodiac constellations. The planets are always found on or near the ecliptic, while the 5° tilt of the moon’s orbit around Earth keeps our natural satellite within a palm’s width of the ecliptic, too. When full, the moon sits on one side of the teeter-totter of the ecliptic while the sun is at the opposite end. Since the sun is high at noontime during May, June, and July, the midnight full moons in those months are low in the night sky. The reverse happens in winter.

Since sunlight is hitting the moon face-on when its full, no shadows are cast from its topography. Instead, the moon’s geology is enhanced – especially the contrast between the bright, ancient, cratered highlands and the darker, younger, smoother maria. All of the variations in brightness you see arise from differences in the reflectivity, or albedo, of the lunar surface rocks.

Early astronomers coined the term maria “seas” for the dark patches on the moon before telescopes revealed that they were actually not wet at all! The very large, round, dark mare in the upper left (northwestern) part of the moon is Mare Imbrium “the Sea of Showers”. The maria to its south are patchy and interconnected. Mare Insularum “the Sea of Islands” is located directly south of it. Mare Cognitum “the Sea that has become Known” sits to its south. Small Mare Humorum “Sea of Moisture” and larger Mare Nubium “Sea of Clouds” are southernmost, to the left and right, respectively.

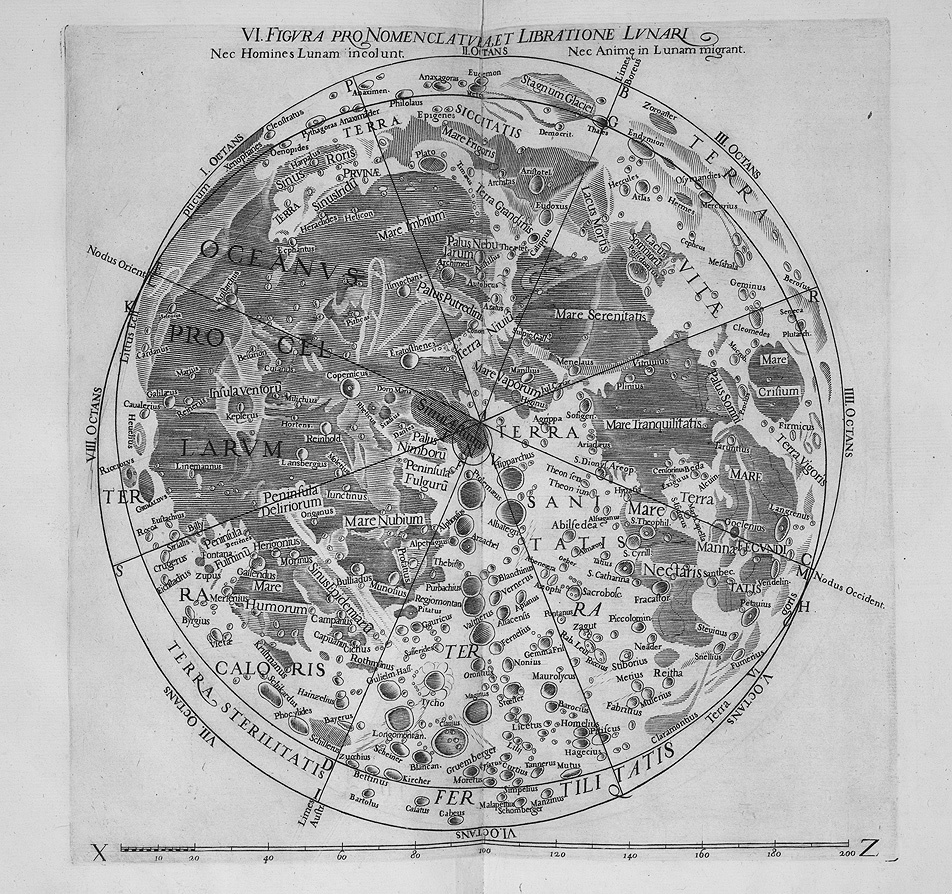

The terms “maria” (the dark regions) and “terra” (the heavily cratered bright regions) were coined by Galileo Galilei after he began to view the moon in his little telescope around 1610. By the middle of that century telescopes were readily available and many scientists set about documenting the heavens. A Dutch cartographer Michael van Langren (1598-1675) aka Langrenus published a complete map of the moon in 1645, but his nomenclature, which mostly corresponded to Catholic monarchs, scientists and artists, was never widely adopted. For example, Oceanus Procellarum on his map was Oceanus Philippicus, named for his sponsor/patron King Philip IV of Spain. In 1647 Polish astronomer Johannes Hevelius published Selenographia. For five years, he carefully observed and sketched the moon, then engraved his maps onto 40 copper plates. He was among the first to highlight the lunar libration effect, the wobble that lets us see more than 50% of the moon’s surface from Earth. His cumbersome naming system classified lunar features as continents, islands, seas, bays, rocks, swamps, marshes and other terrains found on Earth. You can view his map here.

The most popular lunar naming system was developed by Jesuit priest Giovanni Battista Riccioli. Working at the University of Bologna, in 1651 he and his cartographer Jesuit Francesco Maria Grimaldi published a labeled moon map that modern maps have built upon. Riccioli used the names of living and dead scientists and philosophers for the craters, assigning ancient notables to the north of the moon and “modern” (to him, anyway) personages in the south. He placed teachers and their famous students together. The International Astronomical Union (IAU) has continued that policy.

Ricciolo’s maria are all named for weather and states of mind, except for Mare Humboldtianum and Mare Smythii, who were famous explorers, and for Mare Cognitum and Mare Moscoviense, discovered later on the moon’s far side. Fittingly, Riccioli placed the radical proponents of the heliocentric theory, Copernicus, Aristarchus, and Kepler in the Ocean of Storms – and he honoured fellow Jesuits Grimaldi and Clavius with prominent craters.

In the years since the basins were formed, several large craters have been overlain upon them. The prominent crater Copernicus is located in eastern Oceanus Procellarum – due south of Mare Imbrium and slightly northwest of the moon’s centre. Copernicus’ 800 million year old impact scar is visible with unaided eyes and binoculars – but telescope views will reveal many more interesting aspects of lunar geology. Several nights before the moon reaches its full phase, Copernicus exhibits heavily terraced edges (due to slumping), an extensive ejecta blanket outside the crater rim, a complex central peak, and both smooth and rough terrain on the crater’s floor. Around full moon, Copernicus’ ray system, extending 800 km in all directions, becomes prominent. Use high magnification to look around Copernicus for small craters with bright floors and black haloes – impacts through Copernicus’ white ejecta that excavated dark Oceanus Procellarum basalt and even deeper highlands anorthosite.

Grab your binoculars and look for the many ray systems spreading across the full moon’s face. The rays are composed of material that has been thrown radially outwards when objects that slammed into the moon created its more recent craters. The rays are particularly apparent when the moon is lit face-on, as it is around the full phase. Viewed in a telescope, major rays can be shown to be chains of small secondary impact craters excavated by the falling chunks of excavated rock (or ejecta), and by the scattered debris itself. Impacts on the light-coloured lunar highland rocks tended to spread white rays over the surrounding darker mare regions – but sometimes the inverse happens.

Some ray systems are enormous – spanning half the moon’s disk! The ray system of the crater Tycho is a fine example of that. Tycho is the very bright crater located in the south central part of the moon. Its rays are largely missing on the left-hand (lunar western) side, suggesting that its impactor, an asteroid 8 to 10 km in diameter, arrived from the west at an angle less than 45° above the lunar surface, throwing the ejecta in front of it, mainly to the east. In a telescope, you can see that Tycho is encircled by an asymmetrical dark blanket of rubble that is about as wide as the crater’s 85 km diameter. The dark colour is probably basaltic rock excavated from deep below the crust. Tycho and its rays are bright because it is a relatively young crater – only about 109 million years old. The dinosaurs were walking the Earth when the violent event happened! It’s too bad they couldn’t leave us a record of what they saw!

The small crater Proclus is located at the lower left edge of Mare Crisium, the round grey basin near the moon’s upper right edge (northeast on the moon). Proclus’ bright rays only extend toward the right-hand side of the crater, mainly onto Crisium – again due to a very shallow impact trajectory. Many of the dark maria have a single white ray crossing them. Can you trace them back to their origin?

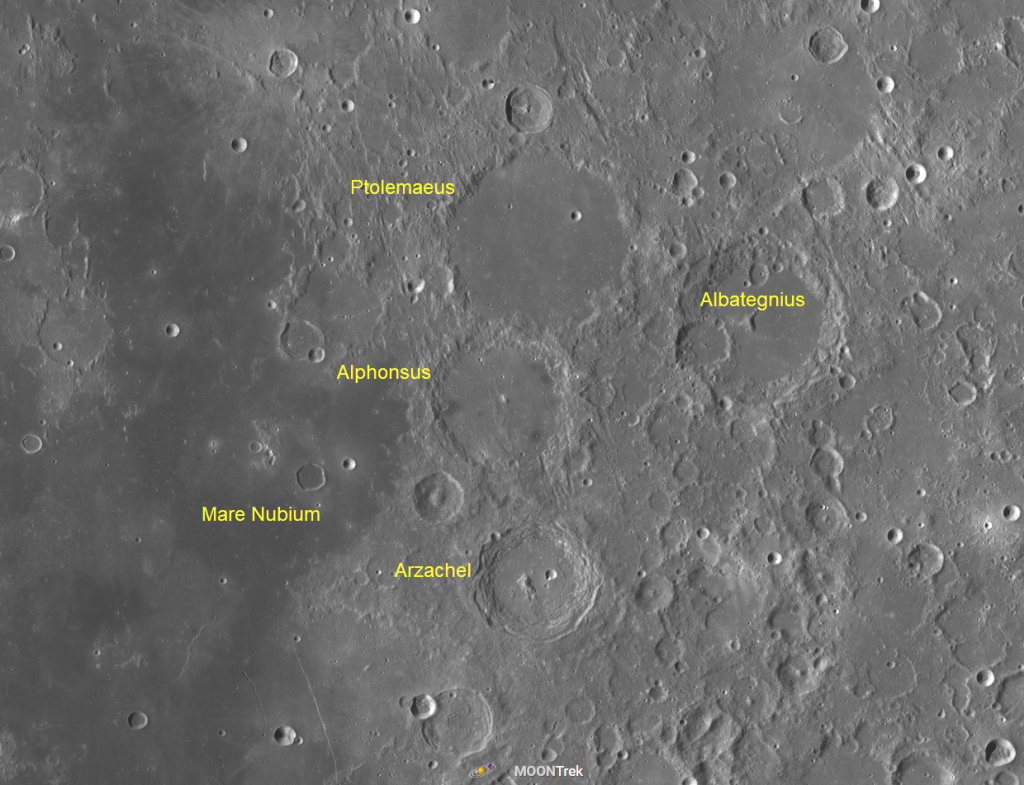

While the moon is quite full, you can use your telescope to look at the dark stains left behind by extinct volcanoes on the moon! Alphonsus is a 110 km wide crater located just south of the moon’s centre, on the upper right shore of Mare Nubium. Any size of telescope will reveal a triangle formed by dark spots on the crater’s floor near its left and right rims. Those are ash deposits. Atlas, another crater with similar markings, sits in the northern region of the moon, about halfway between the northern shore of Mare Serenitatis and the edge of the moon.

Every culture around the world has developed its own stories about the full moon, and has assigned special names to each full moon. The indigenous Ojibwe groups of the Great Lakes region call the May full moon Zaagibagaa-giizis “Budding Moon” or Namebine-giizis, the “Sucker Moon”. For them it signifies a time when Mother Earth again provides healing medicines. The Cree of North America call it Athikipisim, the “the Frog Moon” – the time when frogs become active in ponds and swamps. The Cherokee call it Ahnisguti, the “the Planting Moon”, when the fields are plowed and sown. In the Mi’kmaq lunar calendar, this is Etquljewiku, the Frog-Croaking Moon. In European cultures, the moon is commonly called the Full Milk Moon, Full Flower Moon, or Full Corn Planting Moon.

In the Americas, Thursday evening’s “full” moon will be shining very close to Scorpius’ brightest star, reddish Antares. Skywatchers located in southeastern North America, across northern and eastern South America, the Ascension Islands, and across the Atlantic to west central Africa will be able to watch the moon cross in front of (or occult) Antares through binoculars and backyard telescopes. The surrounding regions will see the moon pass very close to the star. Use an app like Stellarium to look up your own times for the event. In Miami, the moon will cover the star from 9:13 to 10:19 pm EDT.

After Thursday, the moon will wane in phase and rise about an hour later each night, leaving the sky after evening twilight darker for stargazing. On Friday night it will rise at about 10:30 pm local time. It will spend Saturday night shining within the constellation of Sagittarius (the Archer) and then lingering into morning daylight in the southwest on Sunday morning.

The Planets

As of this morning (Sunday) all the planets are positioned west of the sun on the ecliptic. In other words, they will all be rising before the sun in the eastern morning sky. You may have seen some posts on social media excitedly trumpeting a planetary alignment. While technically true, these gatherings happen every few years and don’t trigger anything cataclysmic. Moreover, bright Venus and Jupiter, plus rather faint Uranus, will all be too close to the bright sun to be seen from anywhere on Earth.

The planets will be the most “tightly” spaced together on Thursday, when both Jupiter and Venus (again, not visible from anywhere) will be 71° from Saturn, or about seven fist widths held at arm’s length. Mercury, Mars, and Neptune, which ARE visible, will be strung in a line between them. I’m not setting my alarm. Oh – and for Pluto fans, that distant object will be in the morning sky, too – but 46° even farther west from Saturn.

Only two planets will be easily to see with your unaided eyes – and then only until the brightening sky hides them. The medium-bright, yellowish dot of Saturn will rise just before 3 am local time and clear the rooftops in the east about an hour later. Reddish Mars will rise around 4 am. Mars will appear to be a wee bit brighter than Saturn. Far fainter, blue Neptune will be located on the line joining Saturn and Mars, a fist’s diameter to the lower left (or 11° to the celestial east) of Saturn. This year, Neptune will be positioned a bit more than a thumb’s width to the upper left of a medium-bright star named 27 Piscium. They’ll share the view in binoculars. Other less-brilliant stars nearby named 29 Piscium, 24 Piscium, and 20 Piscium will help guide you to Neptune.

The outermost planet will become easier to see with each passing week. The tipped-over ecliptic is keeping all the planets low in the morning sky. As we get closer to the June solstice, the ecliptic will climb closer to vertical and lift the planets under it. Furthermore, everything is rising about half an hour earlier per week due to our orbit around the sun. For example, on July 7, Saturn will start rising before midnight and Jupiter will join the evening sky from September 4 onwards. Like Saturn, Neptune will be a star-party target from late summer on.

Saturn’s rings, which will effectively disappear when they become edge-on to Earth next March, already appear as a very narrow slash across the planet’s globe. Good binoculars can hint at Saturn’s rings and any telescope will show them. For telescope-owners, Earth’s perspective of the Saturn system this year and next will produce frequent transits of Saturn’s moons and their black shadows across its disk. In a telescope, Mars’ position on the far side of the sun from Earth will keep the planet looking small.

Observers located in the tropics who have unobstructed views to the east-northeast will be able to spot Mercury shining just above the horizon before sunrise this week. The speedy planet will be heading back toward the sun every morning so the viewing opportunity is closing. Turn all optics away from the eastern horizon before the sun rises.

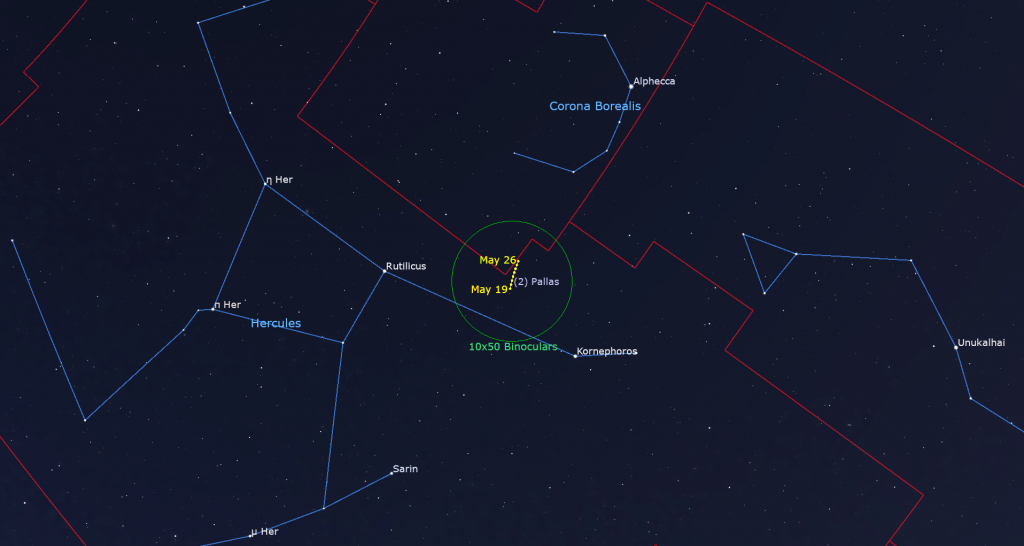

Today, Sunday, May 19, the main belt asteroid designated (2) Pallas will reach opposition, its closest approach to Earth for the year. On the nights around opposition, Pallas will shine with a peak visual magnitude of 9.1, which is within reach of a backyard telescope. The asteroid will be located above and between the bright double star Zeta Herculis, which marks the upper right corner of Hercules’ keystone shaped body, and the star Kornephoros, which shines at Hercules’ elbow. Pallas itself will spend May sliding downward (to the celestial south) between those stars. The asteroid and nearby stars will already be climbing the eastern sky after dusk and will spend the night crossing the sky together.

Public Astronomy-Themed Events

Every Monday evening, York University’s Allan I. Carswell Observatory runs an online star party – broadcasting views from four telescopes/cameras, answering viewer questions, and taking requests! Details are here. They host in-person viewing on the first clear Wednesday night each month. Other Wednesdays they stream views online via the observatory YouTube channel. Details are here.

On the first clear weeknight this week (May 21 to 23) the public are invited to Binoculars Stargazing on the lawn at the David Dunlap Observatory. Arrive for this free program at sunset. You’ll learn to use star charts and basic observing techniques, and then use your binoculars to follow a guided tour through the night sky by RASC Toronto Centre astronomers, and stay after the tour to practice your new skills. Please wear / bring appropriate supplies for being outside. Note that there is no building or washroom access during this program. All participants under the age of 16 must be accompanied by an adult. As this program is weather dependent, please visit RASC Toronto’s home page or Facebook page for a GO or NO-GO call.

On Friday, May 24 from 9:30 pm to 11:30 pm, RASC Toronto Centre will host Family Night at the David Dunlap Observatory for visitors aged 7 and up. You will tour the sky, visit the giant 74” telescope, and view celestial sights through telescopes if the sky is clear. This program runs rain or shine. Details are here, and the link for tickets is here.

Spend some time in the other dome at the David Dunlap Observatory! On Saturday, May 25, you can join me in my Starlab Digital Planetarium for an interactive journey through the Universe at DDO. We’ll tour the night sky and see close-up views of galaxies, nebulas, and star clusters, view our Solar System’s planets and alien exo-planets, land on the moon, Mars – or the Sun, travel home to Earth from the edge of the Universe, hear indigenous starlore, and watch immersive fulldome movies! Ask me your burning questions, and see the answers in a planetarium setting – or sit back and soak it all in. Please note that all guests will sit on a clean floor. A registered adult must accompany all registered participants under the age of 16. We run sessions geared to junior astronomers in the morning and family sessions in the afternoon. Registration is required. More information and the registration links are here.

On Sunday afternoon, May 26 from 12:30 to 1 pm EDT, head to the David Dunlap Observatory for in-person DDO Sun Fun. Safely observe the sun with RASC Toronto astronomers! During the session, which is for ages 5 and up and runs rain or shine, a DDO Astronomer will answer your questions about our closest star – the sun! Registrants will learn how the sun works and how it affects our home planet, view the sun through solar telescopes, weather permitting, and visit the giant 74” telescope. More information is here and the registration link is at ActiveRH.

Keep your eyes on the skies! I love getting questions and requests. Send me some!