The Bright Buck Moon Hangs Low, Morning Mars Takes Aim at Uranus, and Sights for Moonlit Nights!

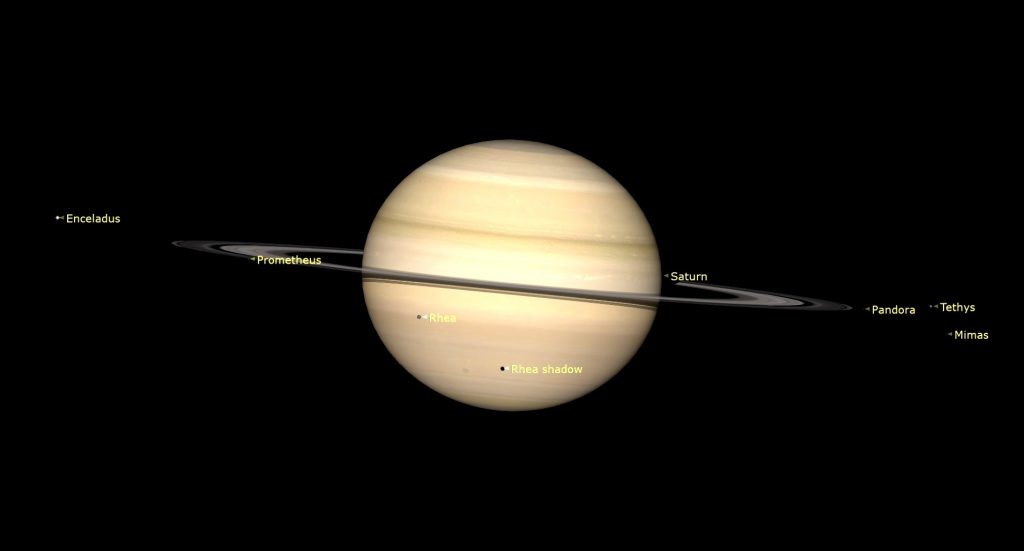

This image taken by the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter shows the fascinating Aristarchus Plateau. The crater Aristarchus at lower right is very prominent, and can be seen even with unaided eyes as a very bright patch. To its left is the similar-sized, but darker crater Herodotus. Vallis Schröteri, the largest sinuous rille on the moon, starts at a broad section near Herodotus, called the Cobra’s Head, and winds to the north, tapering along the way. All of those features sit within the elevated, rough-surfaced, diamond-shaped plateau.

Hi, mid-July Stargazers!

Here are your Astronomy Skylights for the week of July 14th, 2024 by Chris Vaughan. Feel free to pass this along to your friends and send me your comments, questions, and suggested topics. You can also follow me on Twitter as @astrogeoguy! Unless otherwise noted, all times are expressed in Eastern Time. To subscribe to these emails please click this MailChimp link.

If you’d like me to bring my Digital Starlab portable inflatable planetarium to your school or other daytime or evening event in Simcoe, Grey, and Bruce Counties, or deliver a virtual session anywhere, contact me through AstroGeo.ca, and we’ll tour the Universe, or the Earth’s interior, together! My book with John A. Read entitled 110 Things to See With a Telescope is a guide to viewing the deep sky objects in the Messier List – for both beginners and seasoned astronomers. DM me to order a signed copy!

The moon will dominate the evening and overnight sky this week as it waxes toward full next weekend, so I share some interesting aspects of it to check out, and share some ideas for stargazing on bright moonlit evenings with unaided eyes and binoculars. Mercury reaches max visibility in the west after sunset, Saturn holds court after midnight, and Jupiter watches Mars brush with Uranus before sunrise. Read on for your Skylights!

The Moon

Earth’s natural night-light will gleam in the evening and late-night sky worldwide this week as it waxes toward full. That will spoil our enjoyment of the summer Milky Way. Fortunately, the advancing sunset times in late summer and early autumn let us enjoy summer delights beyond their season!

Today (Sunday) the moon will rise in mid-afternoon. It’s perfectly safe – and fun – to observe the moon in the daytime as long as you avoid aiming any optics towards the sun. To enhance the contrast, wear polarized sun glasses or the 3D glasses you get at the movies. Tilt your head and watch the sky darken around the moon.

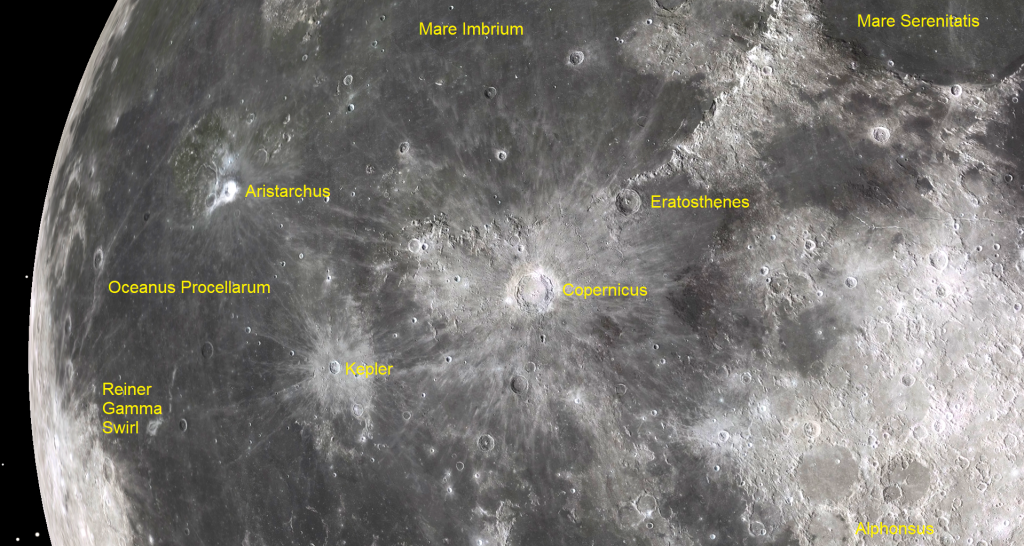

The pole-to-pole terminator will pass north-south through the large and circular Imbrium Basin, alternatively known as Mare Imbrium. Use any size of telescope to look for sinuous wrinkle ridges slithering over the seemingly flat floor of that large mare. The three spectacular and tall mountain ranges that ring the eastern half of the basin will still look spectacular. The dark, round, and smooth crater named Plato will break up the northern arc of the Alpine Mountains. A curving chain of little mountain peaks will poke out of Imbrium’s gray floor below Plato. Those include Montes Recti, Montes Teneriffe, and the single peaks of Mons Pico and Mons Piton. At the southern edge of the big circle, the Apennine Mountain range sinks almost out of sight after it passes the peaked crater Eratosthenes.

The only bright star near Sunday evening’s moon will be Spica, which it occulted yesterday. The moon will spend Sunday in Virgo (the Maiden) and then slide east into Libra (the Scales) for Monday. On Tuesday evening, the bright, waxing gibbous moon will pose to the right (or celestial west) of the up-down row of medium-bright stars that form Scorpius’ claws. You might need binoculars to see them against the 79%-illuminated moon.

On Tuesday, all of Mare Imbrium will be illuminated, plus a good amount of the dark expanse of Oceanus Procellarum to its west. Early astronomers coined the term maria (Latin for “seas”) for the dark patches on the moon. Later, telescopes revealed that they were actually not wet at all! The very large, round, dark mare filling the northwestern part of the moon is Mare Imbrium “the Sea of Showers”. The maria to its south are patchy and interconnected. Mare Insularum “the Sea of Islands” is located directly south of it. Mare Cognitum “Sea that has Become Known” sits to its south. Small Mare Humorum “Sea of Moisture” and larger Mare Nubium “Sea of Clouds” are southernmost, to the left and right, respectively. There is an excellent enlargeable, labelled moon map here.

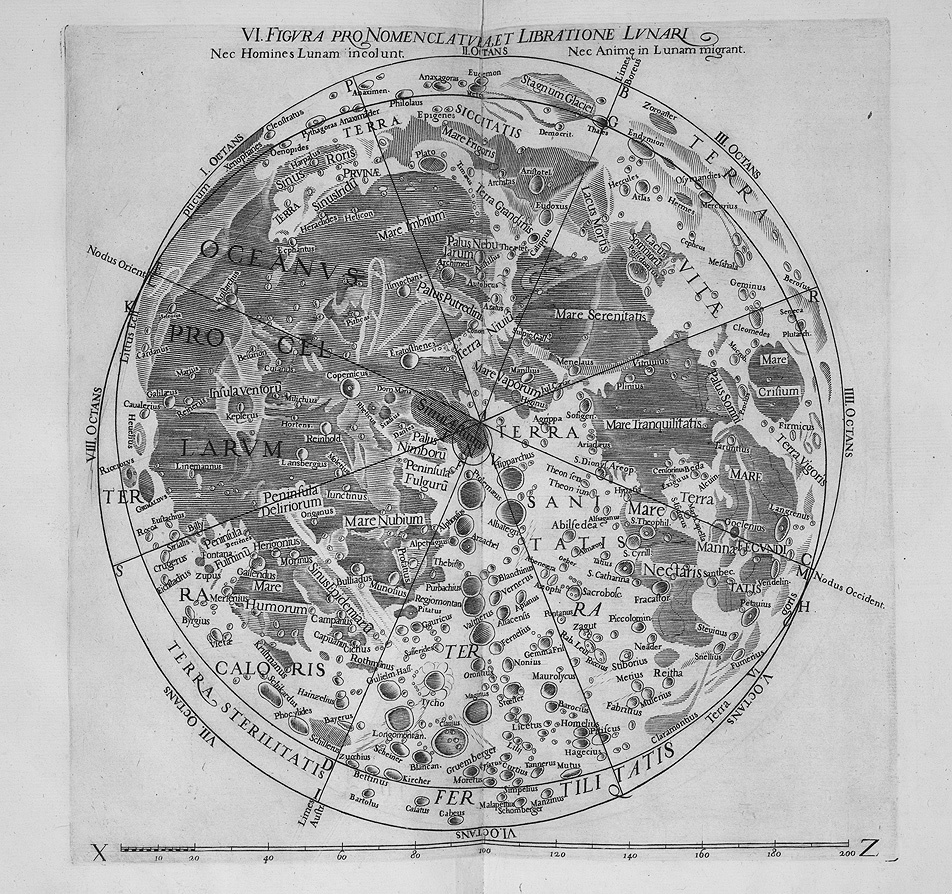

The terms maria and terra (the heavily cratered bright regions) were coined by Galileo Galilei after he began to view the moon in his little telescope starting in late 1609. The rest of the moon’s naming system was largely developed by Jesuit priest Giovanni Riccioli, who published a labeled moon map in 1651 that modern maps built upon. Riccioli used the names of living and dead scientists and philosophers for the craters, assigning ancient notables to the north of the moon and “modern” (to him, anyway) personages in the south. He placed teachers and their famous students together. The International Astronomical Union (IAU) has continued that policy.

The maria are all named for weather and human states of mind, except for Mare Humboldtianum and Mare Smythii, who were famous explorers, and for Mare Moscoviense, which was discovered later on the moon’s far side. Fittingly, Riccioli placed the radical proponents of the heliocentric theory, the scientists Copernicus, Aristarchus, and Kepler, within the Ocean of Storms – and he honoured fellow Jesuits Grimaldi and Clavius with prominent craters. Grimaldi’s big, dark crater will be visible right along the moon’s terminator on Sunday night and then farther from it on Monday.

From Tuesday through Friday, the western half of the moon will fill with light, leaving a diminishing strip of shadow to grace the moon’s western cheek. That zone will continue to reward magnified views.

In the time since the basins were formed, several large (and many small) craters have been punched into them. The prominent crater Copernicus is located in eastern Oceanus Procellarum – due south of Mare Imbrium and slightly northwest of the moon’s centre. Copernicus’ 800 million year old impact scar is visible with unaided eyes and binoculars – but telescope views will reveal many more interesting aspects of lunar geology. Several nights before the moon reaches its full phase, Copernicus exhibits heavily terraced edges (due to slumping), an extensive ejecta blanket outside the crater rim, a complex central peak, and both smooth and rough terrain on the crater’s floor. Around each full moon, Copernicus’ ray system, extending 800 km in all directions, becomes prominent. Use high magnification to look around Copernicus for small craters with bright floors and black haloes – impacts punched through Copernicus’ white ejecta that excavated dark Oceanus Procellarum basalt and even deeper highlands anorthosite.

On Wednesday evening in the Americas, the 87%-lit moon will shine a few finger widths to the left (or celestial east) of Scorpius’ brightest star. The red giant star Antares represents the heart of the scorpion. Its name means “Rival of Mars”, the red planet it resembles and occasionally shines close to. Hours earlier, observers with sharp eyes and binoculars or telescopes across the southern continental Africa and Madagascar can watch the moon cross in front of (or occult) Antares. Surrounding regions will only see the moon pass close to (or graze) the star. You can use an app like Stellarium to look up the circumstances of the occultation for your location.

By the time we see the moon on Thursday evening in the Americas, it will be stepping into the constellation of Sagittarius (the Archer), though you will likely only notice one nearby star – bright Antares twinkling off to the moon’s right. Three prominent craters break up the expanse of Oceanus Procellarum, the widespread dark region on the moon’s left-hand side. Large Copernicus is the easternmost of the craters. Its extensive, ragged ray system intermingles with that of the smaller crater Kepler to its southwest. The very bright crater Aristarchus positioned northwest of them occupies the southeastern corner of a diamond-shaped plateau that is one of the most colorful regions on the moon. NASA orbiters have detected high levels of radioactive radon there. Use a telescope and high magnification to view features like the large, sinuous rille named Vallis Schröteri. Its snake-like form begins between Aristarchus and next-door crater Herodotus and meanders across the plateau.

For observers in the Western Hemisphere the moon will look full on Saturday night – but a razor-thin band along its western limb will still be dark. That’s the left-hand edge for folks viewing the moon from the Northern Hemisphere, and the left-hand edge for southerners. Craters there will still cast shadows while the rest of the moon will look less dramatic under magnification. The moon only appears full when it is opposite the sun in the sky, so full moons always rise in the east as the sun is setting, and set in the west at sunrise. Since sunlight is hitting the moon face-on at that time, no shadows are cast. All of the variations in brightness you see arise from differences in the reflectivity, or albedo, of the lunar surface rocks, making the moon look less arresting under magnification.

The moon will reach its full phase on Sunday at 6:17 am EDT or 3:17 am PDT and 10:17 Greenwich Mean Time, after it has set in the Eastern Time Zone. (Moon phases occur independently of Earth’s rotation.) When you see the bright moon rise in the east around 10 pm next Sunday night, the band of shadow will have switched over to the eastern limb. The rest of the moon will be streaked by lunar rays, material ejected from the younger craters. They are very obvious in binoculars!

The moon’s orbit is inclined by about 5.1° to the ecliptic. That allows it to wander by up to that distance above (north) or below (south) the ecliptic. (The wandering also prevents us from having solar and lunar eclipses monthly.) This full moon and last month’s full moon both occur close to the June solstice, the time when the ecliptic and sun will be highest at local noon. That will once again put the full moon unusually low in the sky because the midnight ecliptic will be low and the moon will be at its near-maximum excursion south of that low ecliptic. The full moon in January, 2025 will be extra high for the same reasons.

The July full moon, commonly called the Buck Moon, Thunder Moon, or Hay Moon, always shines in or near the stars of Sagittarius or Capricornus (the Sea-Goat). The indigenous Ojibwe people of the Great Lakes region call this moon Abitaa-niibini Giizis, the Halfway Summer Moon, or Mskomini Giizis, the Raspberry Moon. The Cherokees call it Guyegwoni, the Corn in Tassel Moon. The Cree Nation of central Canada calls the July full moon Opaskowipisim, the Feather Moulting Moon (referring to wild water-fowl habits), and the Mohawks call it Ohiarihkó:wa, the Fruits are Ripened Moon. All of these names reflect what is happening in nature during this time of the year.

Sights for Moonlit Nights

While the bright moon ruins our views of summertime nebulas this week, we can still enjoy the bright stars, and find a few treats for binoculars.

On mid-July evenings the first stars to appear after dusk are Arcturus and the bright white stars of the Summer Triangle asterism, an unofficial pattern formed using the brightest stars of three different constellations. (Anyone can make up their own asterism!) After dusk, the triangle is halfway up the eastern sky. When you face east, Vega is the topmost star and first to appear. Less-brilliant Deneb sits two fist diameters to Vega’s lower left (or 23° to the celestial east). Altair sparkles three fist diameters to Vega’s lower right (or celestial south) – so the triangle is taller than wide. Despite its name, the asterism appears every summer and remains visible until the end of December!

At magnitude 0.03, Vega is the brightest star in the summer sky, mainly due to its relative proximity to the sun of only 25 light-years. Altair is only 17 light-years from the sun, but Deneb is a staggering 2,600 light-years away. It’s appears bright despite its greater distance because of its far greater inherent luminosity at visible wavelengths.

Keen eyes might reveal that the star Epsilon Lyrae, located just one finger’s width to the lower left (or celestial east) of Vega, is a double star. Binoculars or a small telescope will certainly show you two close-together stars. Examining Epsilon at even higher magnification will reveal that each of those stars is itself a double – hence its nick-name, “the double-double”. Epsilon Lyrae was given its name long before astronomers could see its extra stars using telescopes. The quartet, plus a fainter fifth companion star, are bound together by their mutual gravity, and are slowly orbiting one another in a “cosmic square dance”!

Deneb marks the tail of great bird Cygnus (the Swan). Look for a medium-bright star sitting about two fist diameters to the right (or 22° to the celestial southwest) of Deneb. That’s Albireo, a colourful double star that marks the swan’s head. (I like to think of Albireo as the centre of Doc Brown’s flux capacitor from Back to the Future. The summer triangle’s stars are that gadget’s corners!) Albireo was given only one name before telescopes revealed that it was composed of two stars!

The most southerly of the triangle’s corners is marked by Altair – the head of the great eagle Aquila. In fact, its name translates from “the flying eagle”. At only 16.8 light-years distance, Altair is one of the nearest bright stars – so close that its surface has been imaged! The star also seems to be spinning 100 times faster than our sun, probably generating an equatorial bulge. Like Cygnus, the Aquila the eagle is oriented with its wingtips up-down. The tail bends to the lower right. Two little stars named Tarazed (above, or north) and Alshain (below, or south) sit on either side of Altair, like a balance. As a matter of fact, those two little stars’ names derive from an old-fashioned scale balance. In the Chinese folk tale of The Cowherd and the Weaver Girl, Tarazed and Alshain are children of the cowherd Niú láng 牛郎 (the star Altair), and the princess Zhīnü 织女 (the star Vega).

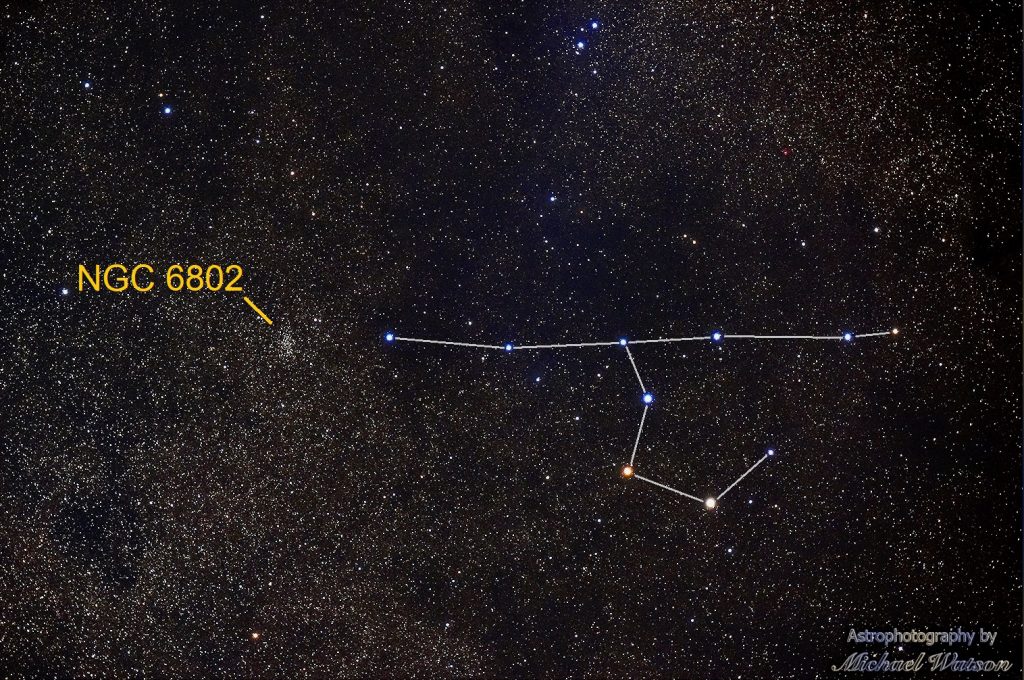

Grab your binoculars and look about midway between Vega and Altair for a little grouping of stars called the Coathangar. It’s composed of a rod made by a line of six stars spanning a thumb’s width in length, plus a hook made up of four stars. (Hint: For North American observers, it’s oriented with the hook downwards to the right.) Its fancier names include Brocchi’s Cluster, Al Sufi’s Cluster, and Collinder 399. A Closer look will show that most of the stars are hot, white A- and B-class stars. The other three are cooler, reddish K- and M-class stars.

About 1.3 fist diameters to the left (or 13° to the celestial northeast) of Altair is cute little Delphinus (the Dolphin). Four stars form a diamond-shaped body and another star to the lower right of that makes the tail! The proper names for Delphinus’ two brightest stars are Sualocin and Rotanev, which are the Latinized form of the English-translated name of Italian astronomer Niccolò Cacciatore, i.e., Nicolaus Venator. Cacciatore wrote the names backwards in a star catalog in 1814 (as a joke, perhaps?), and they snuck through and remained in use!

Stars shine with a colour that indicates their surface temperatures, and this is captured in their spectral classification. Our sun is a yellowish G-class star with a surface temperature of 5,800 Kelvin (or K, for short). The stars of the Summer Triangle are A-class stars that appear blue-white to the eye and have higher temperatures, in the range of 7,500 to 10,000 K. (Being massive balls of gas, stars don’t have a surface. But they do have a radius where they become opaque to visible light, effectively given them the appearance of having a spherical surface.)

High in the southwest, the very bright and orange-tinted star Arcturus might pop into view before Vega. It will spend all evening descending the western sky, and set during the wee hours. Arcturus, which dominates the kite-shaped constellation of Boötes (the Herdsman), is a K-class giant star with a temperature of only 4,300 K. It was once whiter, but it has swelled up and cooled down in old age. Arcturus’ name is derived from Arabic for “follower of the bear”, referring to Ursa Major (the Big Bear). The Big Dipper asterism, made from part of Ursa Major, stretches across the northwestern sky during evening. The dipper’s curved handle “arcs to Arcturus”. Look closely at Mizar, the star where the dipper’s handle bends. A little star named Alcor is close to it. In a telescope, Mizar itself splits into a double star.

Reddish Antares, the heart of Scorpius (the Scorpion), which sits low in the southern sky, is an old M-class star with a surface temperature of 3,500 K. Here’s another trick to see star colours. Aim your telescope or binoculars at a star and unfocus the view so that the point-like star swells into a disk (or donut). You should be able to see that star’s colour better.

The Planets

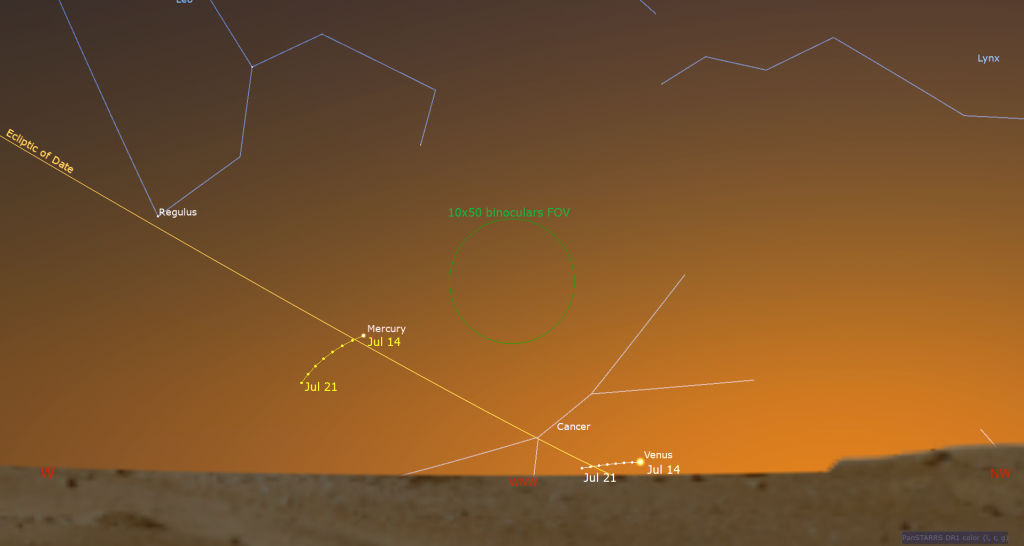

If you are careful to wait until the sun has fully set, you can once again use binoculars to seek out both Venus and Mercury above the west-northwestern horizon on any evening this week. The key will be to have an unobstructed view that is free of clouds and excessive haze.

Venus, currently in Cancer (the Crab), will appear near the place on the horizon where the sun disappeared. At mid-northern latitudes, the best time to look for Venus will start at about 9:15 pm local time. Don’t worry if you miss it, though – Venus will be our brilliant “Evening Star” throughout this coming Fall and Winter.

Mercury will be easier to see because it is much farther from the sun, which lets it set about 1.25 hours after sunset. Next week, Mercury will reach its maximum visibility for its current apparition. For now, at mid-northern latitudes you can start looking for Mercury above the horizon, nearly a fist’s diameter to the left of where the sun set, starting around 9:45 pm local time.

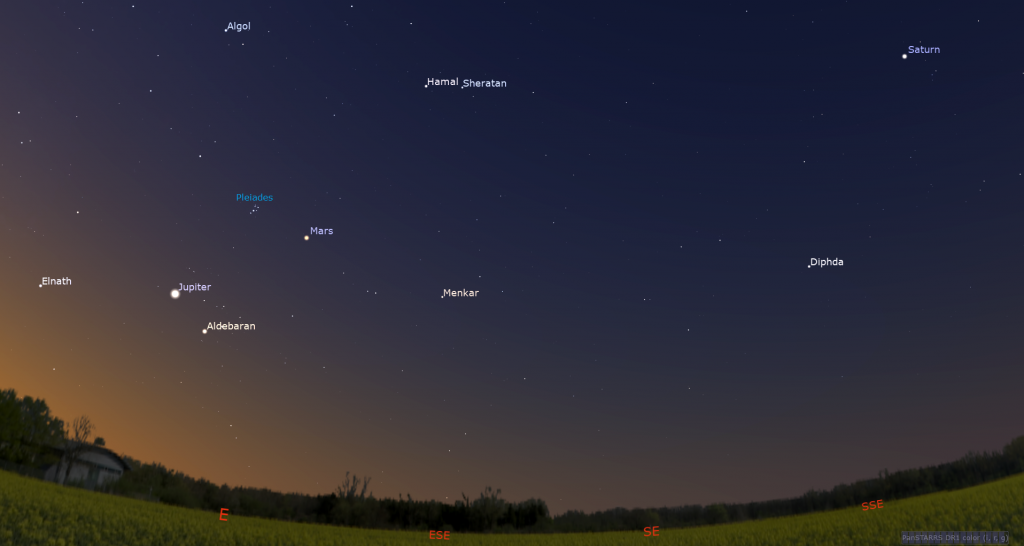

The crowd-favorite planet Saturn will rise over the eastern rooftops by about midnight local time this week. That time will arrive 30 minutes earlier each week. Saturn will spend the next 10 months among the stars of eastern Aquarius (the Water-Bearer). Saturn’s rings, which will effectively disappear when they become edge-on to Earth next March, already look very narrow against the planet’s globe. Good binoculars can hint at Saturn’s rings, and any telescope will show them to you. For telescope-owners, Earth’s perspective of the Saturn system this year and next will cause its moons to align in the plane of the rings and produce frequent transits of Saturn’s moons and their black shadows across its disk.

Neptune will rise about 25 minutes after Saturn and chase it across the sky every night. The remote, blue planet will be spending this year in western Pisces (the Fishes), a generous fist’s width to the lower left (or 11° to the celestial ENE) of Saturn. Neptune will also be located a bit more than a thumb’s width to the upper left (or 2° north) of a medium-bright star named 27 Piscium, allowing them to share the view in binoculars. Other less-brilliant stars nearby named 29 Piscium, 24 Piscium, and 20 Piscium will help guide you to Neptune with a backyard telescope or good, strong binoculars. For now, you’ll need to look at Neptune while it’s higher and the sky is dark between about 1 and 4:30 am local time.

The next planets to appear will be bright, reddish Mars and far fainter Uranus. Both planets will rise at about 2 am local time because they will be holding a morning meeting this week! Mars will remain visible until dawn, when it will appear partway up the eastern sky, with brilliant Jupiter to its lower left. If you head outside while the sky is still dark, the brightest stars of Aries (the Ram) and Perseus (the Hero) will twinkle well above it. In a telescope, Mars will display a small, rusty-coloured disk. Its position on the far side of the sun from Earth will keep the planet looking small until later this year. While everything else rises earlier each week as the sky shifts west due to Earth’s motion around the sun, Mars is traveling in the other direction, like a fish suspended in a flowing river.

Mars’ limited eastward motion has been carrying it towards Uranus. On Monday morning, bright, magnitude 0.95 Mars will pass only 0.55 degrees (or about the full moon’s diameter) south of 86 times fainter, blue-green Uranus. The two planets will be close enough to share the view in binoculars until July 23. On Monday, Uranus’ speck will sit just to Mars’ upper left. From Tuesday onwards, Uranus will shift farther to the upper right of Mars. The duo will share the view in a backyard telescope until Wednesday, but your telescope will likely mirror and/or flip their arrangement. If you check them out, notice that Mars is only 90%-illuminated because its angle from the sun is so great.

The giant planet Jupiter is now well and truly dominating the eastern sky before sunrise. This week it will be rising around 2:45 am local time and then gleaming in the east until sunrise. Take note of the brightest star in Taurus (the Bull), the red giant Aldebaran, shining to Jupiter’s lower right. The planet and the bull will eventually migrate into the late-night and then evening sky later this year as the Earth swings around the sun and varies our perspective of the night sky.

Public Astronomy-Themed Events

Every Monday evening, York University’s Allan I. Carswell Observatory runs an online star party – broadcasting views from four telescopes/cameras, answering viewer questions, and taking requests! Details are here. They host in-person viewing on the first clear Wednesday night each month. Other Wednesdays they stream views online via the observatory YouTube channel. Details are here.

On the first clear weeknight this week (July 15-19) the public are invited to Binoculars Stargazing on the lawn at the David Dunlap Observatory. Arrive for this free program at sunset. You’ll learn to use star charts and basic observing techniques, and then use your binoculars to follow a guided tour through the night sky by RASC Toronto Centre astronomers, and stay after the tour to practice your new skills. Please wear / bring appropriate supplies for being outside. Note that there is no building or washroom access during this program. All participants under the age of 16 must be accompanied by an adult. As this program is weather dependent, please visit RASC Toronto’s home page or Facebook page for a GO or NO-GO call.

On Friday, July 19 from 10 pm to midnight, RASC Toronto Centre will host Family Night at the David Dunlap Observatory for visitors aged 7 and up. You will tour the sky, visit the giant 74” telescope, and view celestial sights through telescopes if the sky is clear. This program runs rain or shine. Details are here, and the link for tickets is at ActiveRH.

Keep your eyes on the skies! I love getting questions and requests. Send me some!