Moonless Nights Provide Plenty of Planets, Meagre Meteors, a Comet, a Pulsing Eye, and Some Tricky Treats!

NGC 457, better known as the Owl Cluster, ET Cluster, and Dragonfly Cluster, was imaged by “Astrodoc” Ron Brecher of Guelph, Ontario. The bright stars are the eyes. The body and feet extend down to the right. Squint to see the upswept, curving chains of stars for the wings.This image covers a finger’s width of the sky left-to-right. View Ron’s other images at www.astrodoc.ca

Hello, Spooky Stargazers!

Here are your Astronomy Skylights for the week of October 27th, 2024 by Chris Vaughan. Feel free to pass this along to your friends and send me your comments, questions, and suggested topics. You can also follow me on Twitter as @astrogeoguy! Unless otherwise noted, all times are expressed in Eastern Time. To subscribe to these emails please click this MailChimp link.

If you’d like me to bring my Digital Starlab portable inflatable planetarium to your school or other daytime or evening event in Simcoe, Grey, and Bruce Counties, or deliver a virtual session anywhere, contact me through AstroGeo.ca, and we’ll tour the Universe, or the Earth’s interior, together! My book with John A. Read entitled 110 Things to See With a Telescope is a guide to viewing the deep sky objects in the Messier List – for both beginners and seasoned astronomers. DM me to order a signed copy!

The moon will spend this week in the predawn sky approaching its new moon phase. That will control the timing of Diwali and deliver dark evenings ideal for viewing departing comet Tsuchinshan, and a late-night sky ready for a few meteors and lots of spooky celestial objects. Meanwhile, all the planets will be available to view, although Mercury will be tough for northerners, and late-rising Mars will be better viewed before dawn. Halloween brings mid-autumn and clocks revert next weekend.Read on for your Skylights!

Halloween Marks Mid-Autumn

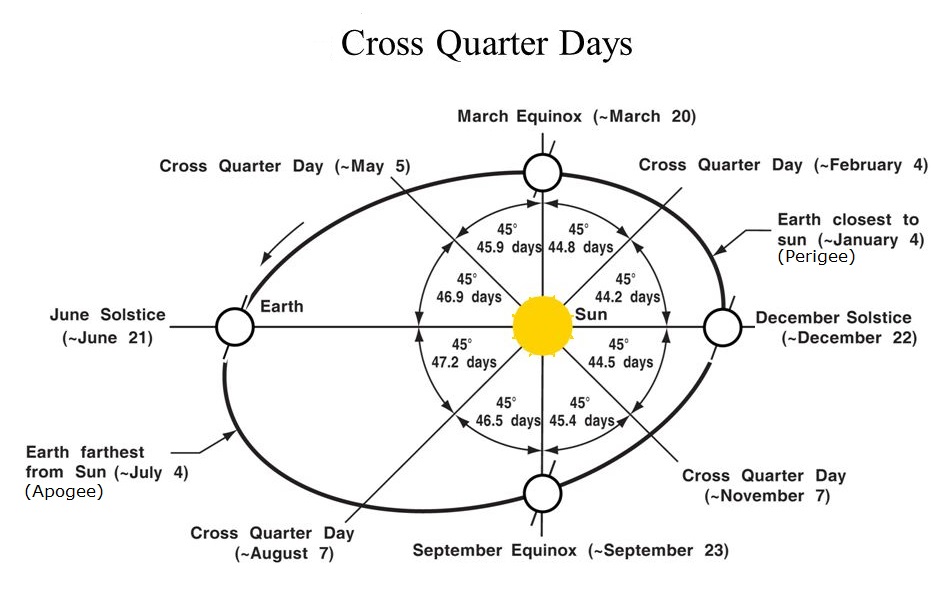

Halloween, or All Hallows’ Eve, has been pinned to the date of October 31 every year. It actually originated from Samhain, a festival observed by the ancient Celts and Druids that was held to mark the end of harvest season and the beginning of winter weather. The Pagan Thanksgiving, perhaps? Astronomically speaking, samhain is one of the four cross-quarter days, the seasonal midpoints that occur halfway between each solstice and equinox.

In modern times, observers of Samhain celebrate it on November 1 – but the true mid-point of autumn will occur next week at 5:21 Eastern time on November 6, 2024. At that time, the ecliptic longitude of the sun will be 225° – extremely close to the double star Zubenelgenubi in Libra (the Scales). The other three cross-quarter days in 2024 are Groundhog Day (or Imbolc) on February 4, May Day (Beltane) on May 4, and Lughnasath or Lammas on August 6.

You can’t merely divide our 365.25-day year into four 91.3-day seasons and then count half that many days to reach the cross-quarters. Planets with elliptical orbits move faster when they are closer to the sun and slower when they are farther away. Since Earth is moving slower at aphelion in July, summers in the Northern Hemisphere are about five days longer than winters!

Happy Diwali!

Like many traditional observances around the world, the timing of the South Asian festival of Diwali, or the Festival of Lights, has an astronomical connection. It lasts five days, always beginning just before the new moon phase that falls between mid-October and mid-November – dubbed “the darkest night of the year”. In 2024, Diwali will commence on Thursday evening, October 31, just hours before Friday morning’s new moon. Expect to hear some fireworks, or to see some colourful lights from celebrants!

Diwali celebrates the triumph of good over evil after the fall harvest. The festival’s name arises from the Sanskrit expression deepa avali, or “rows of lighted clay lamps” – which were set outside when there was no moon to light the way at night.

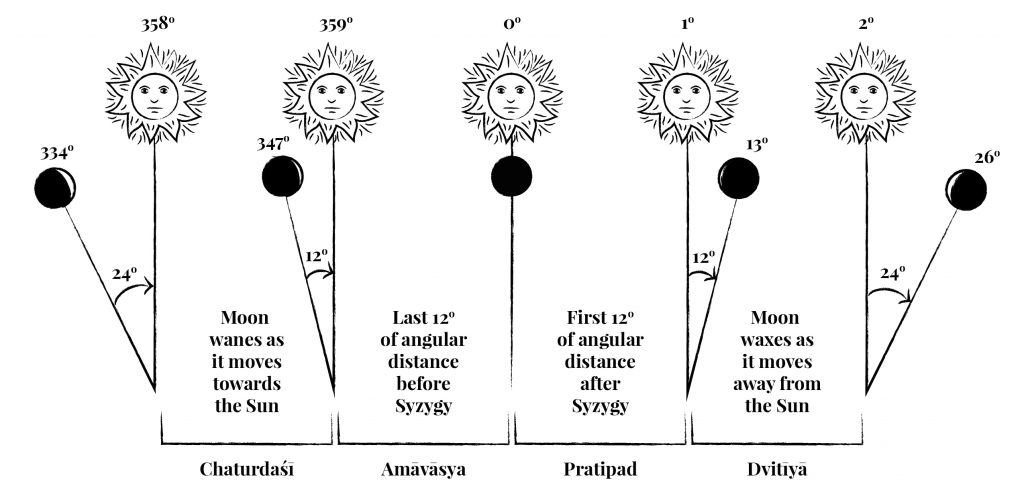

The Hindu lunisolar calendar employs twelve 30-day months within a 360-day year. To avoid calendar drift caused by its annual five day shortfall, it adds an extra (intercalary) month every two or three years, in a pattern that repeats every 19 years. Months commence at the full moon, and are followed by a “bright” fortnight. Each mid-month’s new moon kicks off a “dark” fortnight. The Hindu new year begins around the March equinox. The Hindu month that commences around mid-October on the Gregorian calendar is named Kartik or Kartika.

During its orbit around Earth, the moon varies its angle from the sun by about 12 degrees per day, resulting in 30 unique phases, half of them waxing and the other half waning. Each day of the Hindu lunar month is called a tithi, with each tithi bearing a name associated with a particular illuminated phase. On the day before new moon (or syzygy), the moon is less than 12 degrees west of the sun, and appears as a slim waning crescent. That tithi is called Amāvásyā (Sanskrit: अमावस्या), which literally translates to “no moon there”, since it’s rarely observable. The tithi for the day following new moon (slim waxing crescent) is Pratipada. Diwali always commences on Amāvásyā, the 15th day of Kartika.

Falling Back

For jurisdictions that employ Daylight Saving Time (or DST, for short), clocks should be set back by one hour at 2 am local time on Sunday morning, November 3 – or before you go to sleep on Saturday night. I’ll share some more interesting information about DST next week.

Comet Tsuchinshan Update

Comet C/2023 A3 (Tsuchinshan-ATLAS) has continued to deliver for observers around the globe! The comet is in the western sky during early evening. With the moon gone from the evening sky this week, you can expect to see the comet well through binoculars from a relatively dark location and through any size of telescope under suburban skies – if you know where to look. On Thursday, I saw it with my unaided eyes under a dark, rural sky, where it looked like a true comet with a substantial tail about two finger widths long sweeping up and to the left. The comet will gradually fade as it flies farther and farther from Earth and the sun in the coming weeks.

Comets this prominent are rare, so, it’s worth trying to see this one. I’ll post a sky map showing the comet’s nightly location here. Over this week, its orbital motion will carry it up and to the left (or celestial east) each night through the stars of the lesser-known constellation of Ophiuchus (the Serpent-Bearer). It will move by almost a fist’s diameter over seven nights. At mid-northern latitudes the comet will be setting shortly before 11 pm local time and the sky will be darkening nicely after 7:30 pm. Darkness makes the comet easier to see, but its descent in the western sky will make us see it through more and more of Earth’s atmosphere, dimming it, so the best time to look with your eyes will be between 8 and 9 pm local time. Binoculars and telescopes will work from dusk until about 9:30 pm, when it will be preparing to touch the treetops.

Tonight (Sunday), the comet will be positioned a thumb’s width below (or celestial southwest of) the bright star named Cebalrai (or Beta Ophiuchi). Watch for a nice star cluster named the Summer Beehive sprinkled just above Cebalrai. On Monday the comet will shift to that star’s lower left and become flanked on the left by another star named Muliphen. On Tuesday it will move to a finger’s width above Muliphen. From Wednesday to next Sunday, it will slide above the stars p Ophiuchi and 67 Ophiuchi. The comet is approaching a rich part of the Milky Way, so imagers should frame their photos to include some of the star clusters in the vicinity of the comet, especially the small globular cluster NGC 6426 on Monday and the Summer Beehive until mid-week. Good luck!

Halloween Treats for Binoculars and Backyard Telescopes

It’s time to seek out some spooky treats in honour of Halloween. Before we delve into the night sky, though, take a moment to look west after sunset and spot the bright, orange star Arcturus. During the week before Halloween, that star becomes the Ghost of the Summer Sun! That’s because its sits at the same altitude and azimuth in the sky that the sun did, exactly four months earlier at the same time of the evening – in broad daylight, though. I posted a comparison picture of them here.

One of my favorite spooky objects can be seen in binoculars or any backyard telescope. It’s a large, charming open star cluster designated NGC 457 in W-shaped Cassiopeia (the Queen), but I prefer its common names – the Owl Cluster, ET Cluster, or Dragonfly Cluster. Cassiopeia is located high in the northeastern sky on autumn evenings. The star at the middle of the W is Navi or Gamma Cas. The next bright star below Navi is Ruchbah.

The Owl Cluster consists of two prominent, brighter yellow stars that form the eyes, a sprinkling of dimmer stars that form the owl’s body and feet, and two curved chains of stars that look like upswept wings. Be aware that the critter is positioned with its head pointing away from Cassiopeia. Locate the owl by taking the stars Navi and Ruchbah and making them the two vertices of a right-angle triangle. The cluster sits at the third vertex, where the 90 degree corner is. It’s about four finger widths above Ruchbah – as if the queen is bouncing a baby owl on her knee! Binoculars will show you a tiny bright patch dominated by those yellow eyes. A telescope will see her take flight!

Cassiopeia is surrounded by many big, bright star clusters. Scan around the W on the next clear night and see what treats you can scare up!

The bright, western arc of the giant Cygnus Loop, or Veil Nebula in Cygnus (the Swan), extends through a bright foreground star named 52 Cygni. It’s also nick-named the Witch’s Broom Nebula. Look for it below the left-hand wing of the swan, which sits high in the southwestern sky in evening. Lower in the sky, in the right-hand wing of Aquila (the Eagle), owners of large telescopes can try for the Ghost of the Moon Nebula or NGC 6781. This large planetary nebula is a round, faint, ring nearly four times larger than the full moon! Be warned – it’s faint!

The Skull Nebula (also designated NGC 246) in Cetus (the Whale) is located in the southeastern sky in mid-evening. This planetary nebula’s oval shape and dark voids within it resemble a skull. For a challenge, try to spot Mirach’s Ghost (NGC 404), a magnitude 11.7 galaxy tucked just above the bright star Mirach in Andromeda (the Princess).

Night owls can try for the Witch Head Nebula (NGC 1909 and IC 2118), which will be rising after 10 pm local time this week. This object is actually a reflection nebula – the light from a bright is scattering off of the interstellar dust that it is embedded within – making the same type of blue we see in the sky in daytime. The object is large, too – it measures 3 finger widths high by 1 finger width across. It is centred 2.5 finger widths to the upper right (or to the celestial east) of the bright star Rigel in Orion (the Hunter). It’s a bit dim to see visually.

The Mysterious Demon Star

The star Algol in the constellation of Perseus (the Hero) represents the glowing eye of Medusa from Greek mythology. Also designated Beta Persei, it is among the most accessible variable stars for skywatchers. During a ten-hour period that repeats like clockwork every 2 days, 20 hours, and 49 minutes, Algol dims noticeably and re-brightens by about a third when a fainter companion star with an orbit nearly edge-on to Earth crosses in front of its much brighter primary, reducing the total light output we perceive. Astronomers call that arrangement an eclipsing binary star.

Algol normally shines at magnitude 2.1, similar to the nearby star Almach (aka Gamma Andromedae). But while fully dimmed, Algol’s brightness of magnitude 3.4 is almost identical to Rho Persei (or Gorgonea Tertia or ρ Per), the star sitting 2.25 degrees to Algol’s south. On Wednesday evening, October 30 at 8:53 pm EDT or 00:53 Greenwich Mean Time, Algol will be at its minimum brightness. At that time it will be located in the lower part of the east-northeastern sky. Five hours later the star will return to full intensity from a perch nearly overhead. Observers in more westerly time zones can see the latter stages of the brightening. (Anyone can look up their own dimming times at https://skyandtelescope.org/observing/the-minima-of-algol/.)

Meteor Watching

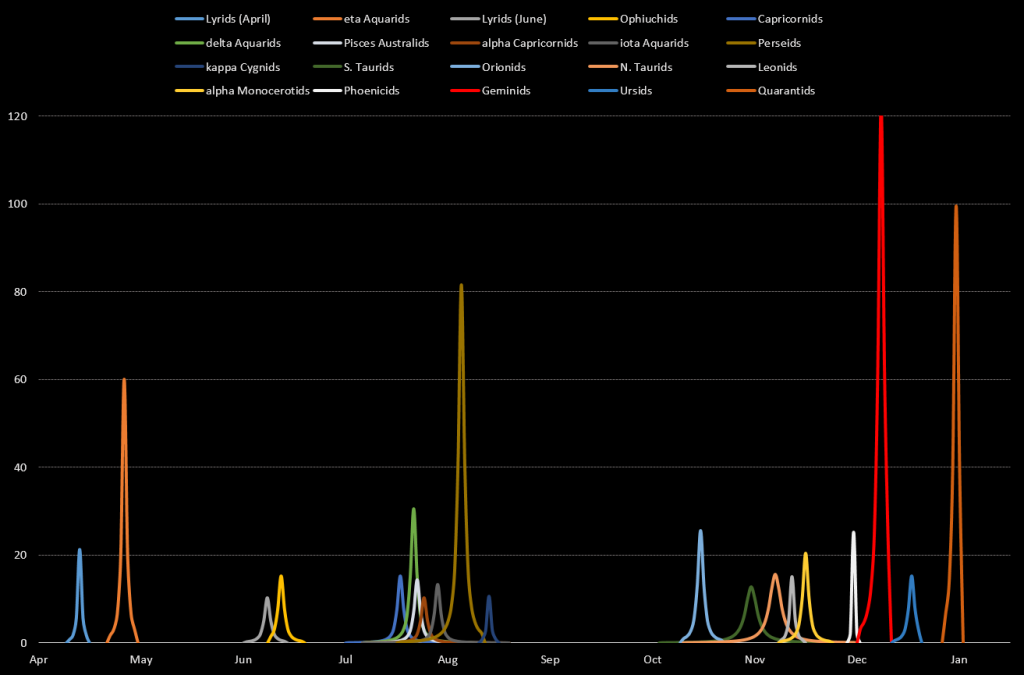

Meteor shower season is well underway! From now until January, Earth will experience eight meteor showers. My late friend Blake Nancarrow created a very informative graph of meteor shower intensity throughout the year.

Now that the moon has left the evening and late-night sky, conditions are ideal for seeing a few shootings stars on any clear night this week. The Orionids Meteor Shower, which is observable world-wide, peaked in the Americas last Sunday, but you should see a few bright and fast-moving stragglers as the shower tapers off over the next few weeks. True Orionids will be travelling in a direction away from a radiant point in the sky near the bright red star Betelgeuse in the constellation of Orion (the Hunter).

Another two minor showers, both derived from debris dropped by periodic comet 2P/Encke, are ramping up. The Southern Taurids meteor shower will peak next Monday night and the Northern Taurids meteor shower will peak on November 11. Both are worldwide showers. (Some showers benefit observers in one hemisphere over the other.) Taurids will be streaking away from a point in the sky between Saturn and Jupiter.

The prolific Leonids meteor shower will start its ramp-up next Sunday.

The Moon

It seems forever since the moon has been gone from the evening sky, but this is the week of the lunar month when our planet’s natural satellite will only be visible after it rises in the east during the pre-dawn hours. It will cross the daytime sky ahead of the sun until it meets our star at new moon on Friday morning and then enter the western sky after sunset on the coming weekend.

If you are outside before sunrise on Monday morning, clear skies will gift you with a view of the pretty, waning crescent moon shining below the stars of Leo (the Lion) and brilliant Jupiter and reddish Mars gleaming high in the south with the winter constellations. Have you wanted to see Orion (the Hunter) without needing your parka and long underwear? Just head outside on late October mornings!

The show will repeat on Tuesday and Wednesday, but the moon will be slimmer and lower – by then in the stars of Virgo (the Maiden). That will be your last view of the moon until next Monday.

The moon will formally reach its new phase on Friday, November 1 at 8:47 am EDT, 5:47 am PDT, or 12:47 Greenwich Mean Time. At that time our natural satellite will be located in western Libra (the Scales) and positioned 3.5 degrees south of the sun. While new, the moon is travelling between Earth and the sun. Since sunlight can only reach the far side of the moon, and the moon is in the same region of the sky as the sun, the moon becomes unobservable from anywhere on Earth for about a day (except during a solar eclipse).

The Planets

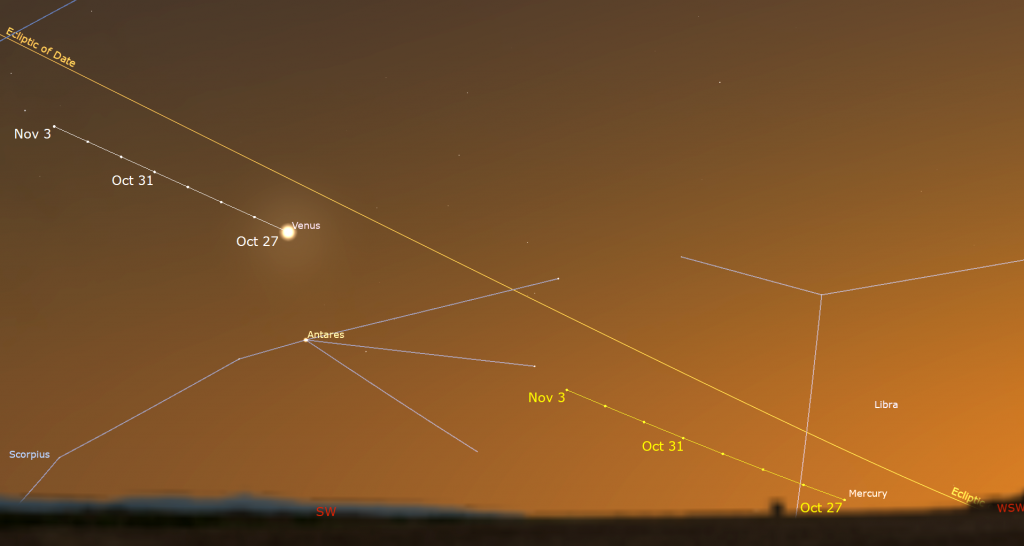

The innermost planet Mercury alternates its appearances between dawn and dusk, staying in view for a while each time and then becoming hidden while it moves past the sun. Since we view Mercury from the moving platform of Earth, Mercury’s appearance intervals alternate between 73 days and 45 days and the number of days we can see it during an apparition varies. For mid-northern latitude observers in Canada and the northern USA, Asia, Europe, and northern Africa, Mercury recently started lurking above the west-southwestern horizon after sunset. Its position 1.5 degrees below (or south of) the severely slanted evening ecliptic is keeping the planet too low in the sky for easy viewing, but if you live close to the tropics or in the Southern Hemisphere, Mercury is putting on a fine and easy showing for you, exhibiting a waning gibbous shape that grows larger every day as it draws closer to Earth.

From now until Mercury once again becomes hidden by the sun’s glare at the end of November, all of the planets will be in the evening sky – yes, including Pluto, which is in the southern sky after dusk. That remote, icy world is too faint to see without an enormous telescope or a set of photos taken over several nights to detect the westward shift of its speck against the background stars of western Capricornus (the Sea-Goat).

Venus is currently twice as far to the east of the sun than Mercury is. That lets the brilliant planet set an hour after Mercury does and lifts it higher above the horizon. The magnitude -4.0 planet will catch your eye low in the southwestern sky after sunset, though you might need to walk around a bit if trees or buildings are blocking your view in that direction. (If you see something bright that is moving left or right, or blinking, it’s an airplane.) Tonight (Sunday) Venus will gleam two finger widths above Scorpius’ brightest star, Antares. The planet is 100x times brighter than that prominent star. After tonight Venus will shift left (or celestial east) with respect to that star.

While Venus increases its angle from the sun every evening, it is waning in illuminated phase and growing larger in telescopes. The distant stars set 4 minutes earlier every night due to Earth’s motion around the sun, but Venus continues to set at about 8 pm local time every night because its eastward orbital motion is counteracting the sky’s westward shift. No matter where you live, Venus will be safe to view through binoculars or a telescope after the sun has completely disappeared. Under magnification the planet will show a blurry (due to the extra air you are looking through) 77%-illuminated disk – like a football.

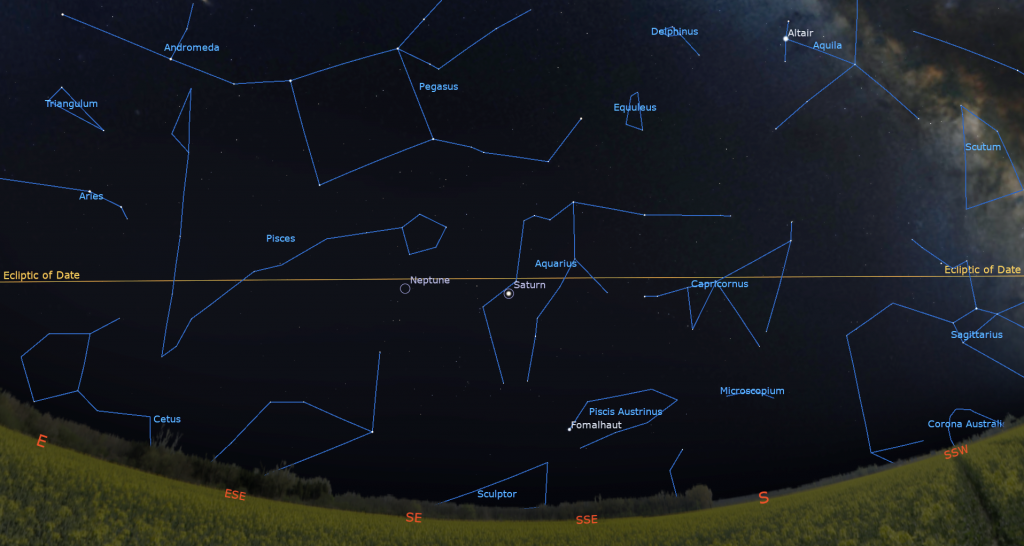

Once Mercury and Venus have set, try for the comet (see above), and then swing around and look southeast for Saturn’s prominent yellowish dot in the lower part of the sky. If your horizon is unobstructed, the bright star Fomalhaut in the constellation of Piscis Austrinus (the Southern Fish) should be twinkling about two fist diameters below, and a little to the right of, Saturn.

The ringed planet will rise in the east in late afternoon, then cross the southern sky all evening long with the faintish stars of Aquarius (the Water-Bearer), and then set the west around 3 am local time. Sharp eyes and binoculars will show you a bent-line trio of stars collectively named Psi1,2,3 Aquarii sparkling to Saturn’s lower left. See if you can tell that the lower two are white, while the higher one is golden. Two redder stars named Phi and Chi Aquarii will appear to Saturn’s left and lower left, respectively. The entire group will fit in your binoculars’ field of view. An even brighter water-bearer star named Hydor will appear just to Saturn’s upper right (or celestial WNW). Saturn is in the midst of a westward retrograde loop, so its position compared to the surrounding stars can easily be detected by looking at them every few days.

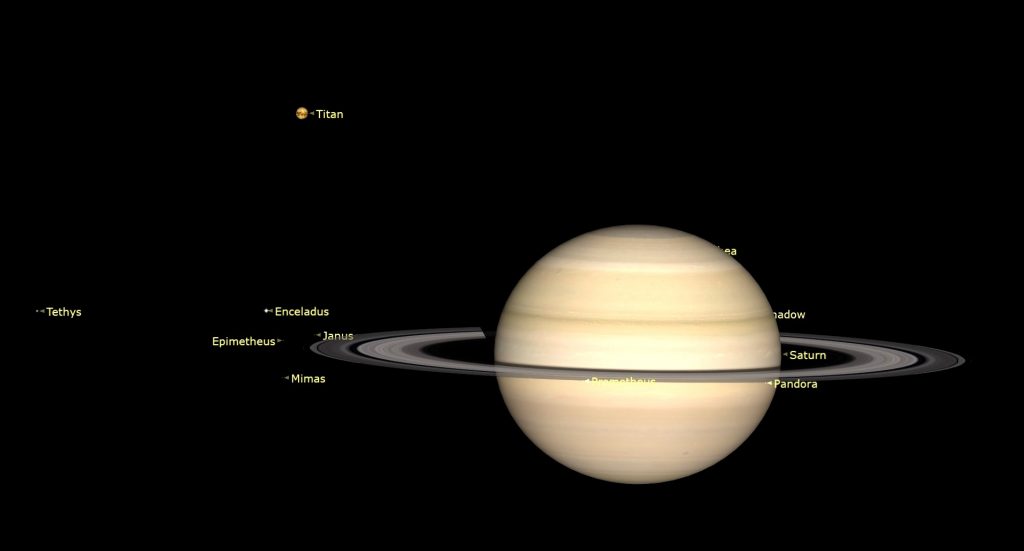

Saturn’s bright, but extremely thin rings effectively disappear when they become edge-on to Earth every 15 years. Since they will do that in late March (while in the pre-dawn sky), the rings already look like a thick line drawn through the planet. Good binoculars can hint that Saturn has rings, but any size of telescope will show the rings and some of Saturn’s larger moons, too. In most years, Saturn’s moons are sprinkled around the planet, unlike Jupiter’s Galileans moons, which are always in a line. But while Earth is close to being aligned with Saturn’s ring plane, its moons fall into an imaginary line drawn through the rings.

Saturn’s largest and brightest moon Titan “TIE-tan” never wanders more than five times the width of Saturn’s rings from the planet. The much fainter moon named Iapetus “eye-YA-pet-us” can stray up to twelve times the ring width during its 80-day orbit of Saturn. The next brightest moons Rhea “REE-ya”, Dione “Dee-OWN-ee”, Tethys “Teth-EES”, Enceladus “En-SELL-a-dus”, and Mimas “MY-mass” all stay within one ring-width of Saturn. You may be surprised at how many of those six you can see through your telescope if you look closely when the sky is clear, dark, and calm.

During this week, Titan will move from above the planet tonight (Sunday), drift well to Saturn’s lower left (celestial east) by Thursday, and then back closer on Saturn’s left by next Sunday night. (Remember that your telescope will probably flip the view around.) The rest of the moons will be tiny specks in a line near the rings. Earth’s perspective of the Saturn system will also cause Saturn’s moons and their small black shadows to frequently cross its disk – but you’ll need a very high quality telescope to watch those.

The distant blue planet Neptune is following Saturn across the sky and setting towards dawn, but viewing that planet requires a large pair of binoculars or a decent backyard telescope. Slow-moving Neptune will spend all of this year in western Pisces (the Fishes). During evening it’s located in the southeastern sky about 1.5 fist widths to the lower left (or 15° to the celestial ENE) of Saturn and a palm’s width below the circle of stars that forms Pisces’ western fish. Use binoculars to find the upright rectangle formed by the medium-bright stars 27, 29, 30, and 33 Piscium. Neptune will be the bluish, dull “star” sitting about two finger widths above (or 2° celestial north of) that box.

The blue-green planet Uranus, which is brighter and easier to see than Neptune, will be climbing the eastern sky during evening. The slow-moving planet will remain about a palm’s width to the right (or celestial southwest) of the bright little Pleiades star cluster in Taurus (the Bull) until 2027! Uranus will climb high enough for viewing in binoculars or a backyard telescope after 9 pm local time. To get you in the vicinity of Uranus, look for the bright star Menkar shining 2.2 fist diameters off to the right of the Pleiades. Uranus will be on the line joining the bottom star of the Pleiades to Menkar.

If you face east after about 9:30 pm, your attention will be drawn to extremely bright, white Jupiter. The big planet will climb the eastern sky through the night and end up very high in the western sky by sunrise. This fall and winter, Jupiter will be positioned between the horn stars of Taurus (the Bull) and a fist’s diameter to the lower left (or celestial east) of the bull’s brightest star, reddish Aldebaran. Jupiter’s westward retrograde loop, which will last until early February, will shift it relative to the bright horn-tip stars Elnath and Zeta Tauri to its upper left and lower left, respectively. Jupiter’s retrograde loop will cover a fist’s diameter in total, but the bull’s horns are more than long enough to contain it.

Any binoculars will show Jupiter’s four Galilean moons named Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto lined up beside the planet. Those moons complete orbits of the planet every 1.7, 3.6, 7.2, and 16.7 days, respectively. If you see fewer than four moons, then one or more of them is crossing in front of or behind Jupiter, or hiding in Jupiter’s dark shadow – or two of the moons are very close together, or one moon is eclipsing or occulting another one. All of the moons will gather to one side of the planet on Wednesday night.

Even a small, but decent quality telescope can show you Jupiter’s dark belts and light zones, which are aligned parallel to its equator. With a better grade of optics, Jupiter’s Great Red Spot, a cyclonic storm that has raged for hundreds of years, becomes visible for several hours when it crosses the planet every 2nd or 3rd night. For observers in the Americas, that GRS will cross Jupiter’s disk on Sunday, Friday, and next Sunday night, and before dawn on Tuesday, Thursday, and Saturday morning. If you have any coloured filters or nebula filters for your telescope, try enhancing the spot with them.

From time to time, observers with good quality telescopes can watch the black shadows of the Galilean moons travel across Jupiter’s disk. In the Americas, the shadow of Europa will cross with Jupiter’s red spot on Sunday night, October 27 between 9:36 pm and 12:55 am EDT (or 01:55 to 04:55 GMT on Monday). Ganymede’s larger shadow will cross Jupiter’s southern polar region on Saturday night between 10:51 pm and 12:41 am EDT (or 02:51 to 04:41 GMT on Sunday).

The reddish dot of Mars will follow Jupiter across the sky after it rises in the northeast at around 11 pm local time this week. Castor and Pollux, the “twin” stars of Gemini will glitter a hand’s width above the red planet. As with Jupiter, you can head outside before sunrise to see Mars sitting high in the southern sky. Mars’ relatively faster orbital motion will increase its separation from Jupiter a little more each morning. On Wednesday, Mars will escape Gemini’s embrace and enter Cancer (the Crab). In a telescope this week, the red planet will appear as a small, reddish disk. Starting next week, Mars will become closer to Earth than the sun is. As it approaches, we will see Mars grow in apparent size and brighten every day until its opposition night on January 15-16.

Public Astronomy-Themed Events

Every Monday evening, York University’s Allan I. Carswell Observatory runs an online star party – broadcasting views from four telescopes/cameras, answering viewer questions, and taking requests! Details are here. They host in-person viewing on the first clear Wednesday night each month. Other Wednesdays they stream views online via the observatory YouTube channel. Details are here.

Keep your eyes on the skies! I love getting questions and requests. Send me some!