Bright Planets Bracket Evening, Medusa Winks, the Morning Moon Covers Spica, and a Peek at Pegasus!

NGC 7479 aka the Superman Galaxy and the Propeller Galaxy is located below (south of) the bright star Markab in Pegasus. One of my favourite galaxies, it is considered peculiar due to its asymmetrical arms. It spans about 1/15th the diameter of a full moon and is visible in larger telescopes on dark nights. This image was taken at the RASC E.C. Carr Observatory by Ian Wheelband in 2017

Hello, End-of-November Stargazers!

Here are your Astronomy Skylights for the week of November 24th, 2024 by Chris Vaughan. Feel free to pass this along to your friends and send me your comments, questions, and suggested topics. You can also follow me on Twitter as @astrogeoguy! Unless otherwise noted, all times are expressed in Eastern Time. To subscribe to these emails please click this MailChimp link.

If you’d like me to bring my Digital Starlab portable inflatable planetarium to your school or other daytime or evening event in Simcoe, Grey, and Bruce Counties, or deliver a virtual session anywhere, contact me through AstroGeo.ca, and we’ll tour the Universe, or the Earth’s interior, together! My book with John A. Read entitled 110 Things to See With a Telescope is a guide to viewing the deep sky objects in the Messier List – for both beginners and seasoned astronomers. DM me to order a signed copy!

The moon will only shine in the morning sky worldwide. It will cover up Spica on Wednesday and reach its new moon phase on the coming weekend. That means we can better see the stars in evening, so I take you on a grand tour of the legendary constellation of Pegasus. Brilliant Venus and Jupiter will gleam on opposite sides of the early evening sky, and then all of them except Mercury and Venus will be observable for many hours of the night. Catch Mars shining near the Beehive. It’s also the time of year when we can watch Medusa close her eye occasionally. Read on for your Skylights!

Medusa’s Eye Pulses

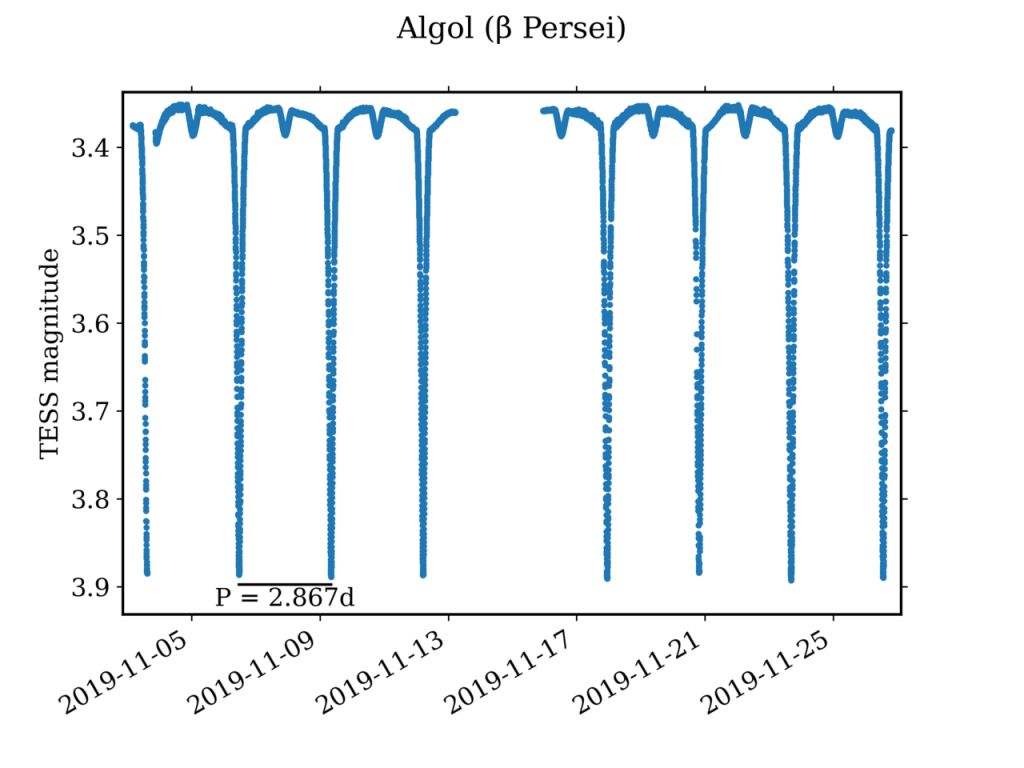

The star Algol in the constellation of Perseus (the Hero) represents the glowing eye of Medusa from Greek mythology. Also designated Beta Persei, it is among the most accessible variable stars for skywatchers. During a ten-hour period that repeats like clockwork every 2 days, 20 hours, and 49 minutes, Algol dims to one-third of its usual brightness and then re-brightens while a fainter companion star with an orbit nearly edge-on to Earth crosses in front of its much brighter primary star, reducing the total light output we perceive. Astronomers call that arrangement an eclipsing binary star system.

Algol normally shines at magnitude 2.1, similar to the nearby star Almach (aka Gamma Andromedae). But while fully dimmed, Algol’s brightness of magnitude 3.4 is almost identical to Rho Persei (or Gorgonea Tertia or ρ Per), the star sitting just two finger widths to Algol’s lower right (or 2.25 degrees to the celestial south).

On Thursday evening, November 28 at 6:03 pm EST or 23:03 Greenwich Mean Time, Algol will be at its minimum brightness. At that time it will be located one third of the way up the east-northeastern sky, with Jupiter well underneath it. Five hours later the star will return to full intensity from a perch nearly overhead. Observers in more westerly time zones can see the latter stages of the brightening.

If you don’t want to wait around for Algol to brighten again, just head out and note the similarity in brightness to Rho Persei and then look again on another night. You can also look up when Algol will be dim by using a nice tool at the Sky & Telescope website, https://skyandtelescope.org/observing/the-minima-of-algol/.

Pegasus Flies on High

Fall and winter evening skies feature a group of easy-to-see constellations that are characters in a grand story from Greek mythology – the tale of Princess Andromeda and her rescue by the hero Perseus. I’ll relate that tale in a future Skylights. This week, we’ll look at Pegasus – the westernmost constellation in the myth. But, first, let’s flesh out that story a little more…

Before hunting the Gorgon Medusa, Perseus was given some magical gifts to aid him in his quest, including winged silver sandals called the Shoes of Swiftness. Immediately after slaying the snake-haired Medusa by cutting off her head, he flew into the air to avoid Medusa’s angry sisters. While hovering there, some of the gorgon’s blood dripped onto the seashore below. Poseidon, god of the Sea, mixed the blood with some sea foam, and the magical flying horse Pegasus, whose name is related to the Greek word for wellspring “pegai”, sprang from the sea.

Pegasus has traditionally been associated with beauty, wisdom, and poetry. In some stories, the majestic, wild, white stallion was tamed by the warrior Bellerophon, the most successful hero of ancient Greece (until Hercules came along later). After many heroic deeds astride Pegasus, Bellerophon felt that the he was worthy of living in Olympus with the gods, and attempted to ride Pegasus there. But the Olympians denied him – sending a bee to sting Pegasus, who bucked and tossed Bellerophon from his saddle. The hero died from the fall to Earth, but he has an interesting role among the stars – as we’ll cover below. Zeus then added Pegasus to his stables, using him to transport thunderbolts. As a reward for his service, at the end of the horse’s days, he was granted a place among the stars.

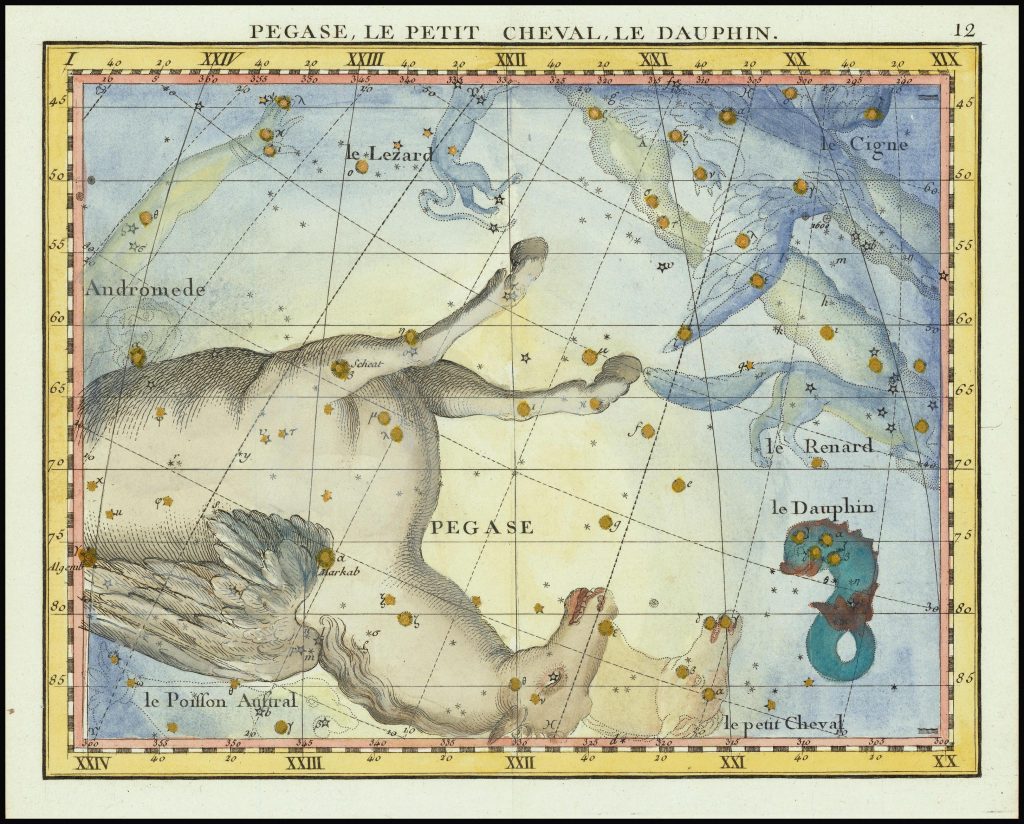

Every year, the constellation Pegasus (the Winged Horse) appears in the eastern evening sky in September, becomes well placed for evening astronomy, high in the southern sky from October to December, and then gradually sinks into the western twilight by February. It is one of the largest and oldest of the 88 modern constellations – 7th by area. Since it occupies a place in the sky just north of the celestial equator, it is visible from almost everywhere on Earth. Only Antarctica never sees it rise.

When viewed from the Northern Hemisphere of Earth, Pegasus has traditionally been depicted as upside-down, with a square of stars representing his wings, and chains of stars extending westward forming his head and neck, and two front legs. The stars where the rest of him should be are occupied by the water constellation of Pisces (the Fishes) – with Aquarius (the Water-Bearer) situated to the right (west), below Pegasus’ head. According to some scholars the ancient Phoenicians envisioned Pegasus as a bridled horse affixed to the prow of their ships – explaining his missing hindquarters and the nautical theme of the surrounding constellations.

To the right (or celestial west) of Pegasus’ head is a tiny and dim constellation composed of four stars called Equuleus (the Little Horse). Some cultures referred to Pegasus as the Second Horse, because Equuleus rose first and led the way across the sky. Beyond Pegasus’ forelegs sits the prominent constellation of Cygnus (the Swan), with its bright Summer Triangle star Deneb. Between Cygnus and Equuleus swims tiny Delphinus (the Dolphin). Lacerta (the Lizard) scampers to the north of Pegasus – “under” the horse’s front feet. Finally, adjoining Pegasus on the left-hand (eastern) side, and sharing one major star with him, is Andromeda (the Princess). Her parents Cassiopeia and Cepheus circle the north celestial pole above her.

Pegasus contains one of the most obvious asterisms in the sky – a giant square made from four, equally bright stars called the Great Square of Pegasus. Its shape will probably remind you of a baseball diamond when you see it, because it’s usually tilted with one corner downwards. An asterism is a shape or pattern in the sky made up of prominent stars – either stars from a single constellation, or a combination of stars from adjacent constellations. The Big Dipper is an asterism that uses only part of its large constellation Ursa Major.

For the Lakota people, the square represented the great shell of Keya, the Turtle. The Anishinaabe of the Great Lakes region view the square as the torso of Mooz, the Moose. Using unaided eyes only, from the suburbs, the Great Square appears empty. Look carefully for two dim stars offset slightly upper right from the centre of the square – they represent the moose’s heart. Hunting of the moose is only allowed while Mooz is visible in the night sky. That way, the calves can be safely born in spring.

In Chinese astronomy, the stars of Pegasus make up the Black Tortoise of the North, one of the four legendary Benevolent Animals in the stars. The pre-Islamic nomadic Arabs saw the square as Al Dalw, the “Water bucket” of Aquarius. To draw water from a deep well, desert travelers would take a water skin and prop the mouth open using crossed sticks lashed to each corner, forming a square opening. When empty, the water skin could be stowed flat or rolled up on the flanks of a camel. The square may also have been, “Al ‘Arkuwah”, the well in which such a bucket was used.

In Arabic astrology, the westerly stars of the Great Square, Markab and Scheat, were together called Al Fargh al Mukdim, the fore-spout (of the bucket). The eastern two stars, Algenib and Alpheratz, were called Al Fargh al Thani, the rear spout. Those two fainter stars inside the square, today designated Tau Pegasi and Upsilon Pegasi, were Salm “a Leather Bucket” and Al Karab “the Bucket-rope”. They may also represent the intersection of the lashed-together sticks holding the bucket open!

Let’s tour Pegasus’s stars. As soon as the sky becomes dark, face the southeastern sky. The square’s edges are about 16° long (or 1.6 fist widths when held at arm’s length), and about 20° from corner to corner. In late November at 6:30 pm local time, the square’s centre is relatively high in the sky. It will reach its highest point in the southern sky at 7:30 pm local time and then set in the west during the wee hours.

The star at the bottom (southeastern) corner of the diamond is Algenib, derived from the Arabic الجنب Al-janb or Al-jānib, “the flank”. It’s a very hot blue-white star of moderate brightness that is located about 350 light-years away from us. It actually emits 4,000 times more light than our sun! Traveling the square counter-clockwise, the white star at the right-hand corner is Markab “the Saddle”. This star appears slightly brighter than Algenib. It emits less light than Algenib, but it looks just as bright because it is closer to us – only 140 light-years away. In some old star atlases, Markab was labelled Matn al Faras, “the horse’s withers”, or “shoulder”.

From Markab, look farther to the right (west) for the dimmer stars that trace the horse’s neck and head. A palm’s width from Markab is the blue star Homam from the Arabic Sa’d al Humām “Man of High Spirit”. Another fist’s width further is Biham, named from S’ad al Biham “lucky stars of the young beasts”. Both stars shine with the same brightness. A somewhat fainter star named Al Fum al Faras “the mouth of the horse” is located a thumb’s width to the right of Biham.

From Biham look a palm’s width higher to the right for bright star Enif, named from الأنف Al’anf “the Nose”. Enif is a low-temperature, orange supergiant star located 670 light-years away from us. It is nearing the last stages of its life cycle. You should be able to perceive that its warm colour. Enif is huge! Were it to replace our Sun, it would span 40° of Earth’s sky, eighty times wider than the sun or moon! Enif is just at the lower mass limit for becoming a supernova. Use binoculars to scan the sky about four fingers widths to the upper right (celestial west) of Enif. You’ll find a small, dim, but pretty, fuzzy patch of stars designated Messier 15. That globular star cluster of 100,000 stars is 33,000 light-years away from us. In a telescope, it will resemble salt sprinkled on velvet.

Resuming our trip around the diamond, the fairly bright, magnitude 2.4 star at the top (northwestern) corner is Scheat “the Foreleg”, the second brightest star in the constellation. That name may arise from the expression Al Sā’id “the upper part of the arm”. Scheat is a cool, red giant star located 200 light-years away from us. Pegasus’ two front legs start at Scheat and extend upwards to the right. Five degrees to the right of Scheat is the dim yellow star Matar, from سعد المطر Al Saʽd al Maṭar “Lucky Star of Rain”. The leg terminates a palm’s width farther in the same direction – at a double star designated Pi Pegasi or π Peg. Using binoculars you should be able to see that Pi consists of two close-together, yellow-white stars.

The second foreleg takes a jog to the lower right (celestial southwest) before bending back up parallel to the first one. A well-spaced pair of yellowish stars named Sadalbari “auspicious star of the splendid one” and Sadalnazi “auspicious star of the camel”, or Lambda Pegasi (λ Peg), marks the knee. That leg continues to the faint white star Iota Pegasi, parked a fist’s width to the upper right, and ends at a dim white star farther along that line named Kappa Pegasi.

There’s a dim yellow star sitting a thumb’s width just outside of the baseball diamond, midway between the top and right corners. This is the sunlike star designated 51 Pegasi. It hosts the first exoplanet ever discovered, in 1995 – a Jupiter-sized planet that orbits that star every 4.23 days at a distance much closer than Mercury does in our solar system. Planets like this are called hot Jupiters. Initially, the planet was nick-named Bellerophon, one of the original riders of Pegasus in Greek mythology. Now it is officially named Dimidium, the Latin word for “half” – since the planet has half the mass of Jupiter. Take a look at the star in your binoculars and let your imagination soar, like Bellerophon!

The final star of the square, at the upper left (northeastern) corner, is called Alpheratz, a name derived from the Arabic phrase سرة الفرس Surrat al-faras “navel of the mare/horse”. It’s another hot, blue-white supergiant star, but it is located only 97 light-years away from us. The spectrum of this star’s light indicates that it is highly enriched in the metal Mercury. In actuality, Alpheratz does not belong to Pegasus. It’s the brightest star in Andromeda, and marks the princess’ head – but that’s a tour for another night!

For Skylights readers with larger aperture telescopes or astro-cameras, Pegasus is loaded with galaxies! This is because the constellation is well away from the obscuring gas and dust of our Milky Way, allowing us to peer deeper into the Universe. One of my favorite sights is NGC 7479, also designated Caldwell 44, an S-shaped spiral galaxy that resembles Superman’s sigil. In fact – the galaxy’s nickname is the Superman Galaxy! Another is the Propeller Galaxy.

A few finger widths above (or 3 degrees to the celestial north of) the midway point along the line joining Matar to Eta Peg, you’ll find a particularly busy assortment of galaxies! The Deer Lick Group is composed of the large, magnitude 9.48 spiral galaxy named NGC 7331, plus a number of minor satellite galaxies, the “Fleas”. Although discovered in 1784 by William Herschel, the unusual name was apparently coined by astronomer Tomm Lorenzin, co-author of “1000+ The Amateur Astronomers’ Field Guide to Deep Sky Observing”, who observed it from Deer Lick Gap in the mountains of North Carolina.

Just half a degree below (south) of the Deer Lick you’ll find the tight little Stephan’s Quintet – a gravitationally bound set of five galaxies. Both sets will all appear together in the field of view of a large aperture telescope at low magnification. It was the subject of one of the first pictures released from the James Webb Space Telescope.

Before you call it a night, take a moment to seek out the Andromeda Galaxy. It is climbing the eastern evening sky. An all-night target, this large spiral galaxy, also designated Messier 31, is only 2.5 million light years away from us, and subtends an area of sky measuring 3 by 1 degrees – that’s six full moon diameters by two! Under dark skies, the galaxy can be seen with unaided eyes as a faint smudge located 1.4 fist diameters to the left (or 14 degrees to the northeast) of the square of Pegasus. The three westernmost stars of Cassiopeia (the Queen) – namely Caph, Shedar, and Navi, also conveniently form a triangle that points downwards towards Messier 31. Binoculars will reveal the galaxy better. In a telescope, use low magnification and look for M31’s two smaller companion galaxies, the foreground Messier 32 and more distant Messier 110.

Next week, I’ll tell you Andromeda’s story.

The Moon

The moon will be completely absent from the evening sky worldwide this week, allowing us to enjoy the celestial sights of the autumn sky after dinner. From now until Saturday, our natural satellite will show a lovely, waning crescent phase while it slides steadily closer to the sun in the eastern pre-dawn sky. It will rise about an hour later every day and linger longer in the morning daylight before setting in the west in the afternoon.

When the moon rises in the east with the stars of Virgo (the Maiden) during the wee hours of Monday morning it will display an orange-wedge of a crescent. The moon will cruise through the maiden’s stars until Thursday. She’s very elongated!

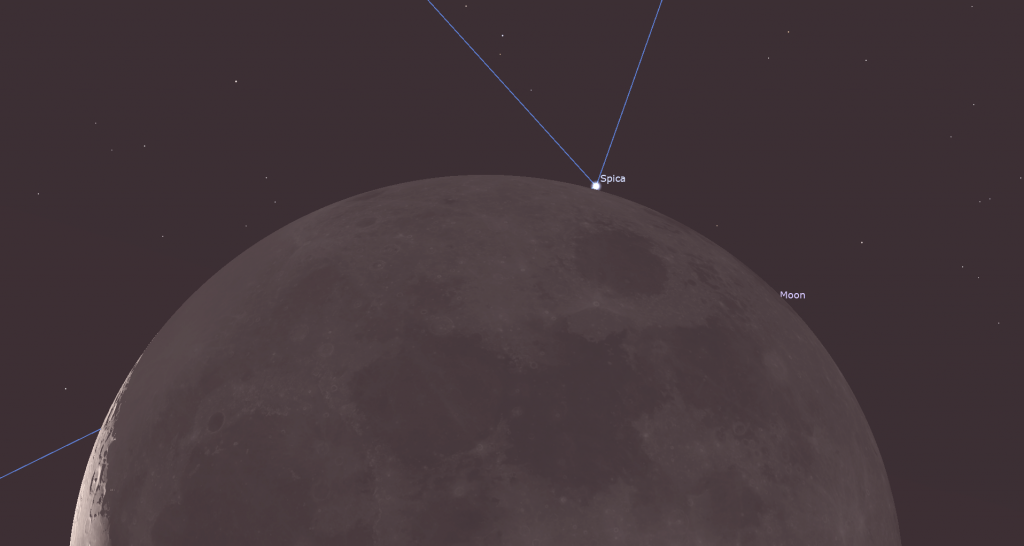

For observers located in a zone covering most of the eastern continental USA and Canada, the old, waning crescent moon will pass in front of (or occult) Virgo’s brightest star, Spica shortly after it has cleared the trees in the east on Wednesday morning, November 27 before sunrise. You can use an app like Stellarium or Star Walk or Sky Safari to look up the times for the occultation where you live.

In Toronto and the surrounding regions, Spica will disappear behind the moon’s lit crescent at about 5:33 am Eastern Time. The star will pop into view from behind the dark limb of the moon near Mare Crisium around 6:44 am EST, as the sky is beginning to brighten. Lunar occultations are safe to view with your unaided eyes. Binoculars or any size of telescope will show the event at its best. Start watching a few minutes before each stage of the event.

After another night in Virgo, the extremely thin crescent moon will slide into Libra (the Scales) for Friday – but by the time the moon has cleared the rooftops in the southeast, morning twilight will have stolen the stars. That will be our last glimpse of the moon before it meets the sun.

The moon will reach its new phase next Sunday at 1:21 am EST or 06:21 GMT (which converts to 10:21 pm PST on Saturday evening). At that time our natural satellite will be located within Scorpius and 4.5 degrees south of the sun. While it’s new, the moon is travelling between Earth and the sun. Since sunlight can only reach the far side of the moon, and the moon is in the same region of the sky as the sun, the moon becomes unobservable from anywhere on Earth for about a day (except during a solar eclipse).

Next week, Earth’s planetary partner will return to shine in the western sky after sunset.

The Planets

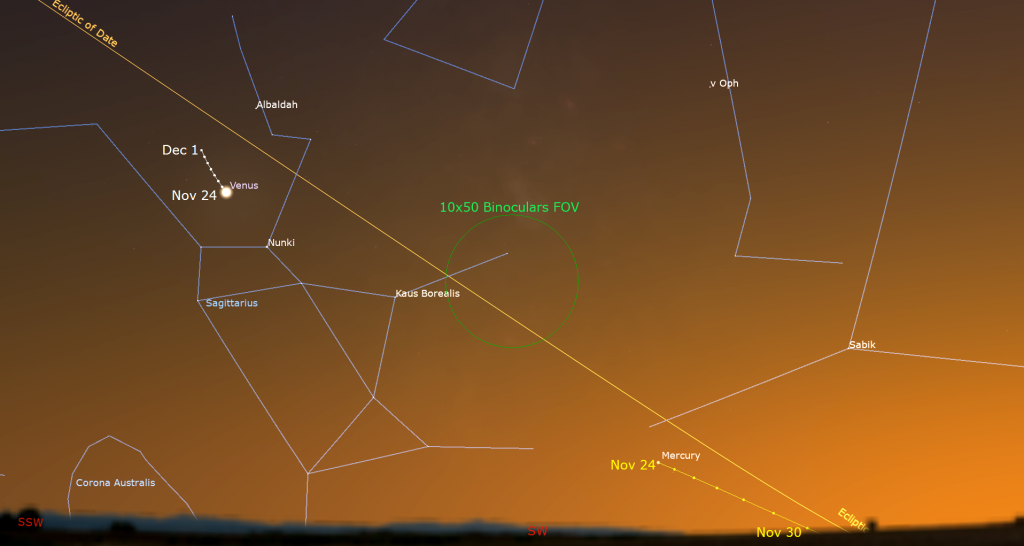

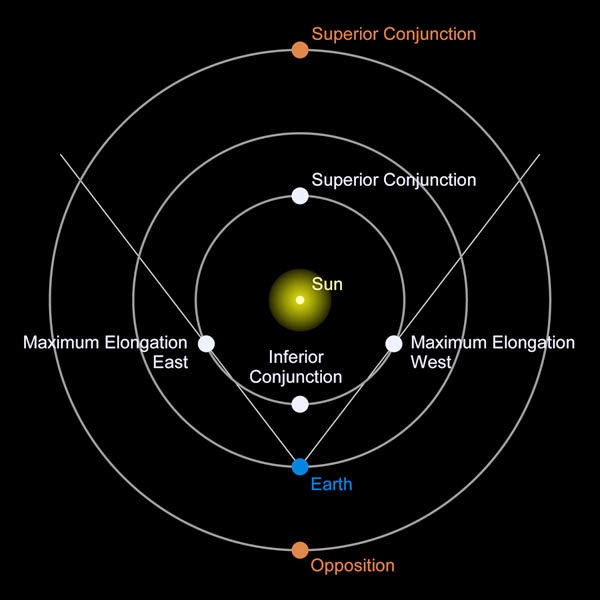

Mercury will be too low and too close to the sun to be seen easily this week, but the speedy planet will be a small distance above the horizon right after sunset and dropping lower daily. Mercury will pass the sun at inferior solar conjunction on December 5 and then pop back up in the eastern pre-dawn sky towards mid-December. “Inferior solar conjunction” means that the planet has passed the sun in the sky by traversing the space between Earth and the sun, i.e., Mercury is closer to us than the sun is. Venus and Mercury are the only planets that can experience inferior conjunction. Every new moon is an inferior conjunction, too. In a superior conjunction, a planet passes the sun in the sky while it is farther from Earth than the sun is, i.e., it’s on the far side of the solar system from Earth.

The rest of the planets will continue to be visible in the evening and late-night sky during the coming months. Brilliant Venus will gleam in the lower part of the south-southwestern sky after sunset this week. It will catch your eye before the sky has darkened much, but you might need to stand where trees or buildings don’t block your view of it. Venus will be setting around 7:30 pm local time, or about 2.75 hours after sunset, so you have plenty of time to enjoy it. (If you see something bright that is moving left or right, or blinking, it’s an airplane.) The stars of Sagittarius (the Archer) around Venus will have appeared before Venus sets.

Venus’ orbit will increase its angle from the sun every day and swing it closer to Earth, causing the planet to slowly wane in illuminated phase and grow larger in telescopes. Venus will be safe to view through binoculars or a telescope after the sun has completely disappeared. Under magnification the planet will show a 69%-illuminated, bowl shape.

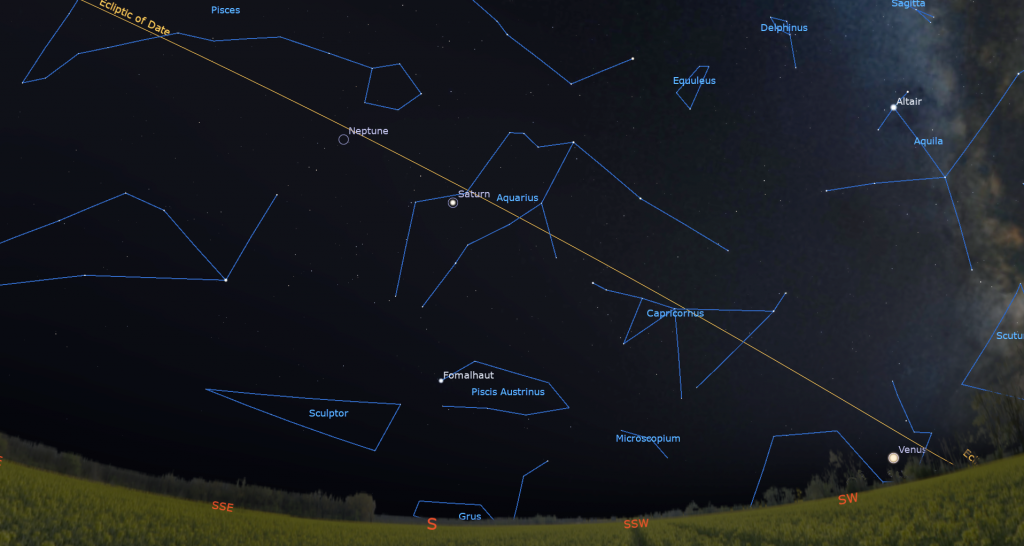

Once the sky is nearly dark, you can see the yellowish dot of Saturn shining not too high up in the southern sky. If you live in a place south of 55° N latitude (where Thompson, Manitoba is, for example), you might also see the bright star Fomalhaut in the constellation of Piscis Austrinus (the Southern Fish) twinkling about two fist diameters below, and a little to the right, of Saturn.

Saturn and the faintish stars of Aquarius (the Water-Bearer) surrounding it will set the west around 12:30 am local time, but you’ll have clear views of the planet in any backyard telescope until about 10:30 pm. Sharp eyes and binoculars will show you a bent-line trio of stars collectively named Psi1,2,3 Aquarii sparkling a few finger widths to Saturn’s lower left, and two redder stars named Phi and Chi Aquarii to Saturn’s left and lower left, respectively. The entire group will fit in your binoculars’ field of view. An even brighter star named Hydor will appear a thumb’s width to Saturn’s upper right (or celestial WNW).

Saturn’s bright, but extremely thin rings effectively disappear when they become edge-on to Earth every 15 years. Since they will do that in late March, 2025, the rings already appear as a thick line drawn through the planet. Good binoculars can hint that Saturn has rings, but any size of telescope will show the rings and some of Saturn’s larger moons, too. In most years, Saturn’s moons are sprinkled around the planet, unlike Jupiter’s Galileans moons, which are always in a line. But while Earth is within months of being aligned with Saturn’s ring plane, its moons remain within a zone drawn through the rings.

Saturn’s largest and brightest moon Titan “TIE-tan” never wanders more than five times the width of Saturn’s rings from the planet. The much fainter moon named Iapetus “eye-YA-pet-us” can stray up to twelve times the ring width during its 80-day orbit of Saturn. The next brightest moons Rhea “REE-ya”, Dione “Dee-OWN-ee”, Tethys “Teth-EES”, Enceladus “En-SELL-a-dus”, and Mimas “MY-mass” all stay within one ring-width of Saturn. You may be surprised at how many of those six you can see through your telescope if you look closely when the sky is clear, dark, and calm.

During early evening this week, Titan will start from off to Saturn’s right (or celestial west) tonight (Sunday), pass just above (celestial north of) Saturn on Thursday, and then swing out to Saturn’s left (or celestial east) by next Sunday night. (Remember that your telescope will probably flip the view around.) The rest of the moons will be tiny specks in a line near the rings. Earth’s perspective of the Saturn system will also cause Saturn’s moons and their small black shadows to frequently cross its disk – but you’ll need a very high quality telescope to watch those.

The distant blue planet Neptune can be seen in a backyard telescope as it follows Saturn across the sky every night, especially while the moon is gone this week. During early evening, search for the slow-moving outer planet in the southern sky, just shy of 1.5 fist widths to the left (or celestial ENE) of Saturn and a palm’s width below the circle of faint stars that forms Pisces’ western fish. Use binoculars to find the upright rectangle formed by the medium-bright stars 27, 29, 30, and 33 Piscium. Neptune will be the bluish, dull “star” sitting about two finger widths above (or 2° celestial north of) that box.

Uranus, Jupiter, and Mars are over in the eastern evening sky. Uranus is located about a palm’s width to the right (or celestial southwest) of the bright little Pleiades star cluster in Taurus (the Bull). If you use your binoculars to find the medium-bright stars named Botein and Epsilon Arietis, Uranus will be the dull-looking blue-green “star” located several finger widths below (or southeast of) them. To get you in the vicinity of Uranus, look for the bright star Menkar shining 2.2 fist diameters off to the right of the Pleiades and down a little. Uranus will be a quarter of the way along the line joining the bottom star of the Pleiades to Menkar. Uranus will look clearest in a backyard telescope after 7 pm local time.

The brilliant planet Jupiter will be rising in the east while Venus is setting in the west. The two bright planets will be at about the same height around 6:20 pm local time. From now until early February, Jupiter will be drifting west between the horn stars of Taurus (the Bull), Elnath and Zeta Tauri. Those stars will shine to Jupiter’s upper left and lower left, respectively. Jupiter’s westerly motion will also carry it steadily closer to the bright, reddish star Aldebaran, which marks the eye of the bull. This week, Jupiter and Aldebaran will be less than a fist’s diameter apart, and closing. Aldebaran, which represents the angry eye of the bull is only 66 light-years away from us. The stars of the Hyades Cluster that form the rest of the bull’s triangular face are considerably farther away, all born of the same collapsed gas cloud.

The winter constellations will shine below Jupiter every day from late evening onward, and then become rotated to the planet’s left after midnight. Jupiter will reach its highest point in the sky, due south, during the wee hours. Then it will descend the western sky and set 30 minutes after sunrise.

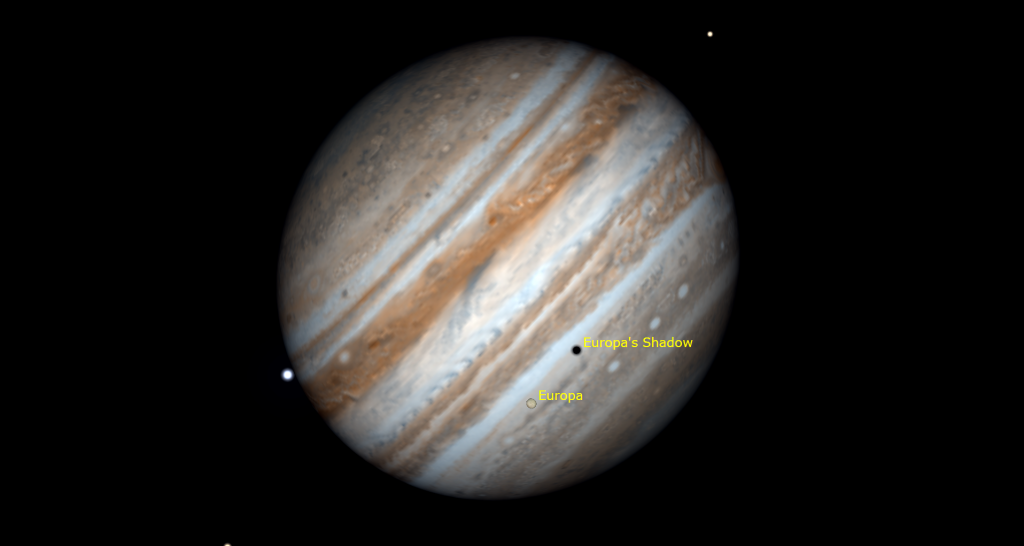

Any size of binoculars will show you Jupiter’s four Galilean moons named Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto lined up beside the planet. Those moons complete orbits of the planet every 1.7, 3.6, 7.2, and 16.7 days, respectively. If you see fewer than four moons, then one or more of them is crossing in front of or behind Jupiter, or hiding in Jupiter’s dark shadow – or two of the moons are very close together, or one moon is eclipsing or occulting another one.

Jupiter will continue to get a little brighter and a little larger until its opposition night on December 7. Even a small, but decent quality telescope can show you Jupiter’s dark belts and light zones, which are aligned parallel to its equator. With a better grade of optics, Jupiter’s Great Red Spot, a cyclonic storm that has raged for hundreds of years, becomes visible for several hours when it crosses the planet every 2nd or 3rd night. For observers in the Americas, that GRS will cross Jupiter’s disk during early evening on Thursday and next Sunday night, and also towards midnight Eastern time on Monday, Wednesday, and Friday night. If you have any coloured filters or nebula filters for your telescope, try enhancing the spot with them.

From time to time, observers with good quality telescopes can watch the black shadows of the Galilean moons travel across Jupiter’s disk. In the Americas, Europa’s little shadow will cross on Thursday, November 28 between 7:37 pm and 10:08 pm EST (or 00:37 to 03:08 GMT).

Mars is getting noticeably brighter now that our distance to has dropped to “only” 119 million km. It will clear the rooftops in the east by about 10 pm local time and ascend the sky a generous fist’s diameter below the bright star Pollux, the lower of the “twin” stars of Gemini. The motion of the red planet through the faint stars of Cancer (the Crab) is slowing as it prepares to start a retrograde loop on December 7. This week, the planet will be shining just above (or celestial north of) the large open star cluster in Cancer known as the Beehive, Praesepe, and Messier 44. Mars and the stellar “bees”, which will be scattered across an area more than twice the size of a full moon, will fit into the field of view in binoculars for several weeks. The planet will be closest to the cluster from next Sunday to Friday and then it will be increasingly farther above the cluster in December.

Early risers can easily see Mars shining high in the southwestern sky at sunrise to the upper left of Jupiter. The winter constellations will be arrayed between those two planets. In a telescope this week, the red planet will display a small, reddish disk. We’ll start seeing surface details as Mars gets closer to Earth every day until its opposition night on January 15-16.

Public Astronomy-Themed Events

Every Monday evening, York University’s Allan I. Carswell Observatory runs an online star party – broadcasting views from four telescopes/cameras, answering viewer questions, and taking requests! Details are here. They host in-person viewing on the first clear Wednesday night each month. Other Wednesdays they stream views online via the observatory YouTube channel. Details are here.

On Sunday afternoon, November 24 from 12:30 to 1:30 pm EDT, head to the David Dunlap Observatory for in-person DDO Sunday Sungazing. Safely observe the sun with RASC Toronto astronomers! During the session, which is for ages 7 and up, a DDO Astronomer will answer your questions about our closest star – the sun! Registrants will be given an eclipse viewer, learn how the sun works and how it affects our home planet, view the sun through solar telescopes, weather permitting. More information is here and the registration link is at ActiveRH.

Keep your eyes on the skies! I love getting questions and requests. Send me some!