A Mini Full Wolf Moon, Saturn Slips Away at Sunset, Venus Joins Morning Mars, and a Peek at Perseus!

This image of the Alpha Persei Moving Group, also known as Melotte 20, was captured by Martin Gembec of Czechoslovakia in 2007. Mirfak is the very bright star above centre. The scattered bright stars are stellar siblings. The golden star to lower left is Sigma Persei. The entire image spans several finger widths left-to-right, or 4 degrees of sky. Wikipedia

Hello, mid-January Stargazers!

Here are your Astronomy Skylights for the week of January 16th, 2022 by Chris Vaughan. Feel free to pass this along to your friends and send me your comments, questions, and suggested topics. You can also follow me on Twitter as @astrogeoguy! Unless otherwise noted, all times are expressed in Eastern Time. To subscribe to these emails please click this MailChimp link.

If you’d like me to bring my Digital Starlab portable inflatable planetarium to your school or other daytime or evening event, or teach a session online, contact me through AstroGeo.ca, and we’ll tour the Universe, or the Earth’s interior, together! My terrific new book with John A. Read entitled 110 Things to See With a Telescope is a guide to viewing the deep sky objects in the Messier List – for both beginners and seasoned astronomers. DM me to order a signed copy!

The night sky worldwide this week will be dominated by the bright moon, starting with Monday’s Full Wolf Moon, the smallest of 2022. Mercury and Saturn will be disappearing sunward, leaving Jupiter and the ice giant planets to view in early evening. Meanwhile, Venus will join Mars in the morning before sunrise. I start a two-part look at the constellation of Perseus. Read on for your Skylights!

The Moon

The moon has always shone down upon the denizens of Earth. At some point, people began to seek to understand our natural environment and to take advantage of the annual variations in the seasons in order to schedule planting, harvesting, hunting, and celebrations. Full moons naturally became celestial time keepers since they were obvious to everyone and conveniently rose at sunset. Moreover, the full moon’s bright light allowed people to be out and about safely at night. It lit the way of the hunter or traveler before modern conveniences like electric lights, and let workers in the fields devote extra hours to get the harvest in.

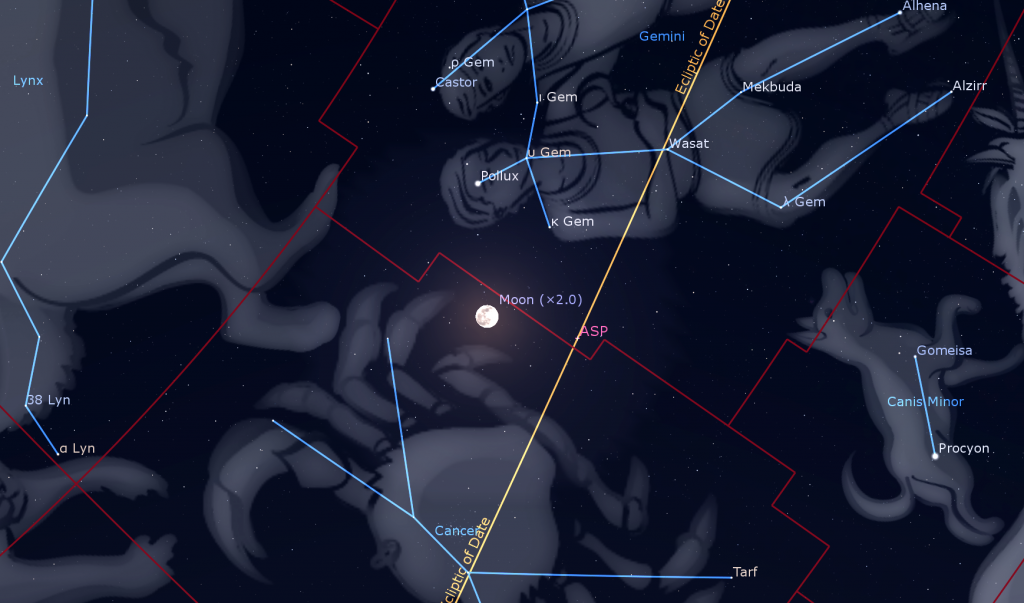

On Monday, January 17 at 6:48 pm EST (23:48 UT or Greenwich Mean Time), the moon will reach its full moon phase. Full moons in January always shine in or near the stars of Gemini (the Twins) or Cancer (the Crab). Since they are, by definition, opposite the sun on this day of the lunar month, full moons are always fully illuminated – rising at sunset and setting at sunrise. Full moons during the winter months at mid-northern latitudes climb as high in the sky as the summer noonday sun, and cast similar shadows.

The moon completes an orbit of the Earth every 27.3 days – its sidereal period. Since the Earth is moving around the sun at the same time, the lunar phases, which are controlled by the angle between the sun and moon in the sky, repeat every 29.5 days – or one synodic period. (The term comes from the Greek word synodikos – a meeting or conjunction of people, or celestial objects.) Doing some arithmetic will show you that there are more than 12 synodic periods in a calendar year – so every third year or so, we’re treated to an extra, thirteenth full moon. Those fall into different months each time, and are commonly referred to as blue moons. The second one in a calendar month is a monthly blue moon. The third one of four within a season is called a seasonal blue moon. The next monthly blue moon will occur on August 30-31, 2023, and the next seasonal blue moon will take place on August 19-20, 2024.

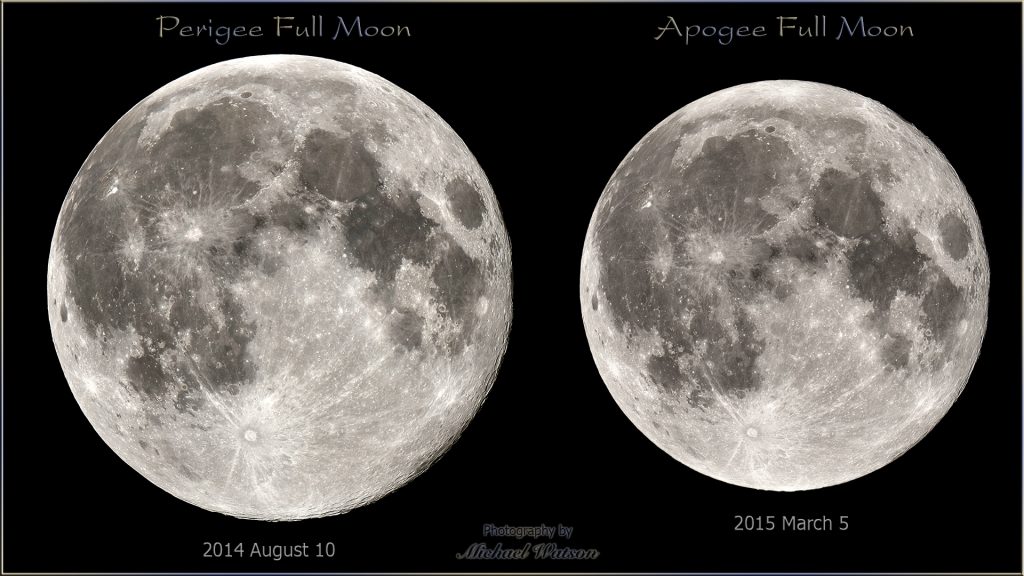

About every 14 months, the sidereal and synodic cycles synchronize for a few months, giving us a series of supermoons. Those are defined to occur when the moon is full while it’s also within 90% of its perigee (closest to Earth), making it look a little bigger and brighter. In 2022, supermoons will shine in June and July. In contrast, Monday’s full moon will occur while it’s near apogee – making this one a mini-moon!

Each society around the world developed its own set of stories for the moon, and every month’s full moon now has one or more nick-names related to human spirit or the natural environment. The Indigenous Ojibwe people of the Great Lakes region call the January full moon Gichi-manidoo Giizis, the “Great Spirit Moon”. (You might recall that name from hearing or singing Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s The Song of Hiawatha.) For the Ojibwe, January is a time to honour the silence, and recognize one’s place within all of Great Mystery’s creatures.

The Algonquin of the Great Lakes call it Squochee Kesos, “the sun has not strength to thaw” moon. The Haida’s of western Canada and Alaska use Táan Kungáay, the Bear Hunting Moon. The Cree of North America call the January full moon Opawahcikanasis, the “Frost Exploding Moon”, when trees crackle from the extreme cold temperatures. For Europeans, the January full moon is commonly known as the Wolf Moon, Old Moon, or Moon after Yule. The Wolf Moon name might be derived from North American First Nations traditions, although some think it has an Anglo-Saxon origin. In either case, it’s likely that the hungry wolves calling to one another in the dead of winter would leave an impression on anyone before our modern era.

Tonight (Sunday) the nearly full moon will be crossing through the giant Winter Hexagon or Winter Football asterism. A magnified view of the moon will show a little strip of darkening along its western (or left-hand) rim as it gleams between the twins of Gemini all night long. That non-illuminated zone will switch to the eastern (right-hand) rim of the moon on Tuesday night. For the balance of this week, Luna will rise later each night and wane in phase. The early sunsets of January allow us to see the waning moon without staying up very late. The same features we are used to enjoying in binoculars and telescopes will now be illuminated by sunlight arriving from the west instead of the east.

From Wednesday to Friday, the moon will be high enough to see after mid-evening while it traverses the stars of Leo (the Lion). On the coming weekend, the moon will be visiting the stars in the Maiden, Virgo – rising before midnight and then lingering into the daytime morning sky. Saturday night will offer a fantastic opportunity to see the mountains ringing the Imbrium Basin under reverse illumination. I described them last week here.

The Planets

We are quickly losing sight of the evening planets as Earth’s orbital motion carries them sunward. On Sunday and Monday after sunset, you might be able to spot Mercury and Saturn shining together just above the west-southwestern horizon. Mercury will be positioned almost a palm’s width to Saturn’s lower right (or ~5° to the celestial west). Visually, Mercury will appear slightly fainter than the Ringed Planet. Mercury will drop out of sight by mid-week, speeding towards inferior solar conjunction next week. Meanwhile, Saturn will exit more gradually – all but disappearing by the coming weekend (unless you live in the tropics, where it will persist a little longer). (Ensure that sun has completely disappeared before pointing optics towards Mercury or Saturn.)

The very bright, white dot of Jupiter will remain in view in the southwestern sky until it hits the trees sometime after 7 pm local time. By then the stars of Aquarius (the water-Bearer) will appear around it. This week, Jupiter will sit low enough in the sky after dusk that its light will be shining through a triple thickness of Earth’s distorting atmosphere – so observe Jupiter as early as you can spot it, while it’s higher. Take long, lingering looks through the eyepiece so that you can catch moments of better clarity. Once Jupiter disappears in a few weeks, we’ll have to wait until August to see a bright evening planet (Saturn)! Jupiter and Mars won’t return until autumn.

Binoculars and small telescopes will show you the Jupiter’s four large Galilean moons named Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto. Since Jupiter’s axial tilt is a miniscule 3°, those moons always look like beads strung on a line that passes through the planet, and parallel to Jupiter’s dark equatorial belts. That line of moons, and the belts, tilt as Jupiter crosses the sky. The moons’ arrangement varies from night to night. Io, for example, orbits Jupiter once every 42 hours. From one night to the next night, 24 hours has elapsed on Earth – time for Io to complete half an orbit and shift from one side of Jupiter to the other. The other Galilean moons move less rapidly, taking between 3.5 and 16.7 days to orbit Jupiter.

The blue planet Neptune is following Jupiter sunward. The distant, dim planet is near the border between Aquarius (the Water-Bearer) and western Pisces (the Fishes), about 1.6 fist diameters to the upper left (or 16° to the celestial east) of Jupiter. If the sky is very dark, Neptune can be seen in good binoculars and backyard telescopes. To locate it, use binoculars to find the sloped grouping of five medium-bright stars: Psi (a triple star), plus Chi, and Phi Aquarii (or ψ, X, and φ Aqr). Neptune’s non-twinkling speck will sit several finger widths to the upper left (or 3 degrees to the celestial NNE) of the top star, Phi. Viewed in a telescope, Neptune’s apparent disk size will be 2.2 arc-seconds. Try to view Neptune in early evening, while it sits higher in the sky. It’ll set by about 9 pm local time.

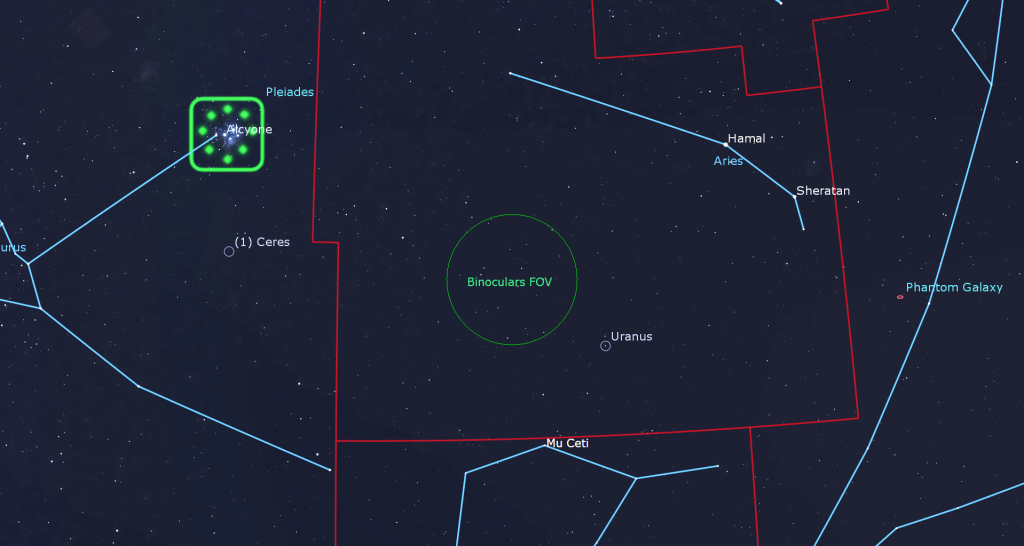

On Tuesday, January 18, the distant, blue-green planet Uranus will temporarily cease its motion through the distant stars of southern Aries – completing a westward retrograde loop that began in late August. After Tuesday, the planet will begin to move eastward again. At magnitude +5.7, Uranus can be seen easily in binoculars and backyard telescopes – and even with your unaided eyes, under dark skies. Look for the planet’s small dot positioned a fist’s width to the lower left of (or 11.5 degrees to the celestial southeast of) Aries’ brightest stars, Hamal and Sheratan. Or use binoculars to locate Uranus using the closer star Mu Ceti, which sits to its lower left. Uranus is also about two fist diameters to the upper right (or 19 degrees to the celestial west-southwest) of the Pleiades star cluster. This week Uranus will be observable all night long – especially around 7 pm local time, when it will have climbed more than halfway up the southern sky.

Early risers can watch for Mars, which will continue its year-long journey to a bright showing at opposition in December, 2022. This week, Mars will rise at about 5:10 am local time. You might spot the magnitude 1.45 planet shining low in the southeastern sky, well to the lower left of its rival, the bright star Antares in Scorpius (the Scorpion). Take care to turn binoculars and telescopes away from the eastern horizon well before the sun rises.

As this week progresses, Venus will join Mars. Look for the very bright, magnitude -4.3 planet gleaming above the east-southeastern horizon once it rises shortly after 6 am local time. Venus will rapidly slide toward Mars during the next couple of weeks. The minor planet designated (4) Vesta will be dancing between them.

A Peek at Perseus

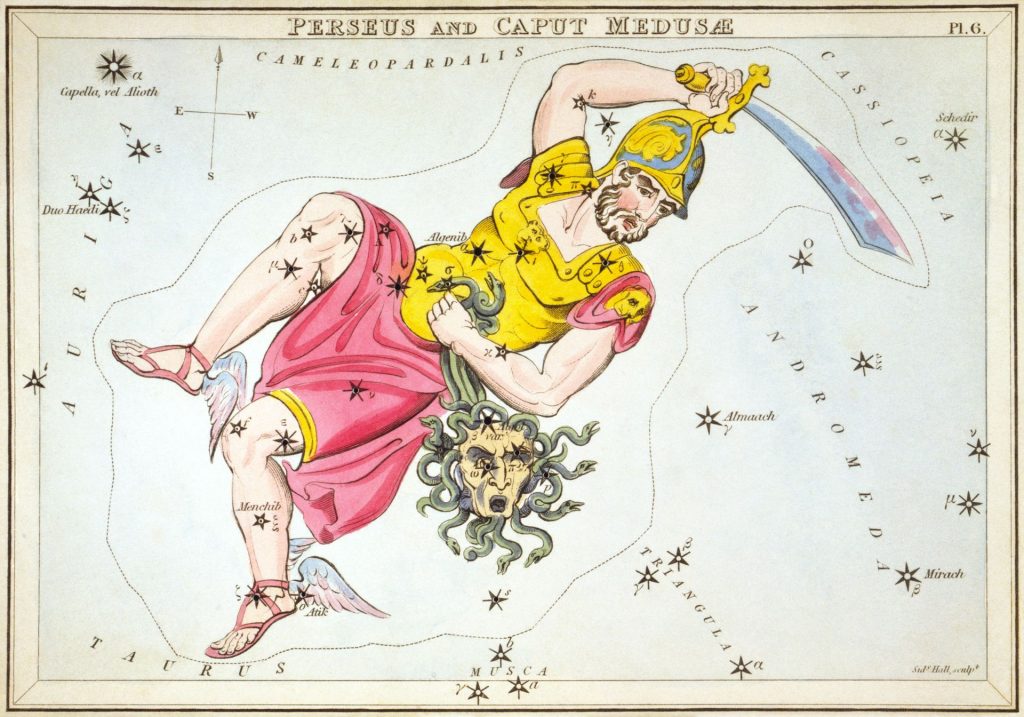

Fall and winter evenings host the constellations involved in the Greek mythology story of Perseus (the Hero) and Andromeda (the Princess). Once upon a time…

Andromeda was the beautiful daughter of Queen Cassiopeia and King Cepheus of Ancient Ethiopia. Through no fault of her own, the princess became the centre of a hair-raising story. After her mother angered the Nerieds (Sea Nymphs) by boasting of Andromeda’s unrivaled beauty, the god of the sea Poseidon (aka Neptune) sent Cetus, the Sea-monster to ravage Ethiopia’s coast. An oracle told King Cepheus that his only solution was to sacrifice Andromeda to Cetus. So she was chained to rocks by the sea-shore.

Meanwhile, King Polydectes of Seriphos had sent the hero Perseus to retrieve the head of the snake-headed Gorgon named Medusa. Before hunting Medusa, Perseus was given some magical gifts to aid him in his quest, including winged silver sandals called the Shoes of Swiftness. Immediately after slaying Medusa by cutting off her head, he flew into the air to avoid her two angry sisters. While hovering there, some of the gorgon’s blood dripped onto the seashore below. Poseidon, god of the Sea, mixed the blood with some sea foam, and the magical flying horse Pegasus, whose name is related to the Greek word for wellspring “pegai”, sprang from the sea.

Perseus, on his winged sandals, happened to be flying by on his way to Seriphos, just as Cetus was about to take Andromeda. She must have been beautiful indeed, because he instantly fell in love with her, slew the beast, and freed her from her chains. After more adventures, including one in which Perseus accidently killed his evil grandfather to fulfill a prophecy, the couple sailed to Argonis, where they raised a family of many children. Hercules was descended from them.

Perseus is one the 48 ancient constellations described by the Greek astronomer Ptolemy in the 2nd Century. His stars are centred midway between the Celestial Equator and Polaris – so part of him is circumpolar for mid-northern latitude observers. The entire constellation can be seen as far as 30° S latitude on Earth, but only during evenings from November to January, when he peeks above the northern horizon.

Perseus’ main stars are enclosed in a square spanning about 26° north-to-south and 22° east-to-west. A peninsula adjoining his northwestern corner grows his territory. Perseus is bordered by the prominent constellations of Taurus and Aries on the south, Auriga on the east, and Andromeda’s mother Cassiopeia to the northwest. Triangulum and Andromeda’s feet are west of him. The faint stars of Camelopardalis lay to his northeast.

In mid-January Perseus is located nearly overhead in the northern sky. The easiest way to identify the constellation is to look for Perseus’ brightest star, named Mirfak, which shines midway between the W of Cassiopeia (to its lower left) and the even brighter, yellowish star Capella in Auriga (to its right). Once you have Mirfak, look for two more stars stepping towards Cassiopeia. From those two, reverse course and travel back through Mirfak and then along a lengthy chain of medium-bright stars that arc towards the bright Pleiades star cluster. That’s his torso and eastern leg. His western leg is composed of another star chain that begins at a grouping representing Medusa’s head. (She’s slung on his hip or held in his western hand.) That leg curves northeast, past Mirfak, and converges towards his head. Together, the chains make a narrowing wedge which points toward the W.

Since the two arcs of stars resemble legs, many cultures saw a human figure in those stars. In contrast, Asian astronomers saw a boat’s keel in the eastern curve of stars, and the Romanians saw a mighty axe called Barda.

This constellation’s location straddling the outer reaches of the Milky Way has filled it with rich star clusters that are perfect for binoculars. The largest of these surrounds the bright star Mirfak, or Alpha Persei. The open star cluster Melotte 20, also known as the Alpha Persei Moving Group and the Perseus OB3 Association, is a collection of about 100 young, massive, hot B and A-class stars spanning 3 degrees of the sky. The cluster can be seen with unaided eyes, and improves in binoculars. It is approximately 600 light years from the sun and is moving through the galaxy as a group. Mirfak is moving with them. It is an elderly, yellow supergiant star that has evolved out of its blue phase and is now fusing helium into carbon and oxygen in its core.

Aim your binoculars midway between Mirfak and Cassiopeia’s W, the realm of the Double Cluster. These two open star clusters, each 0.3 degrees across and approximately 0.45 degrees apart, form a spectacular one degree-wide sight in binoculars or a telescope at low magnification. (That’s twice the width of the full moon!) The more westerly cluster NGC 869 is slightly closer to Cassiopeia. It is more compact, and contains more than 100 white and blue-white stars. NGC 884, the easterly cluster, is a bit more sparse and contains a handful of 8th magnitude golden suns. Use your telescope to see their double stars, mini-asterisms, and dark lanes of missing stars. The two clusters are inside the Perseus Arm of our Milky Way galaxy, about 7,300 light-years from the sun. Their visual brightness has been dramatically reduced by opaque interstellar dust in the foreground.

Next week, I’ll tour you through the interesting stars and objects in Perseus, including Algol (Beta Persei). Algol is nick-named the “Demon Star” Algol because it’s among the most accessible variable stars for beginner skywatchers.

Public Astro-Themed Events

Every Monday evening, York University’s Allan I. Carswell Observatory runs an online star party – broadcasting views from four telescopes/cameras, answering viewer questions, and taking requests! Details are here. Their in-person Wednesday night viewing has been converted to online via the observatory YouTube channel.

My free, family-friendly Insider’s Guide to the Galaxy webcast, now with Samantha Jewett, the Outreach Coordinator of RASC National, returns on Tuesday, January 18 at 3:30 pm EST. My friend Blake Nancarrow will join us to talk about RASC Observing Programs and the certificates and pins you can earn for completing their programs. You can find more details and the schedule of future sessions here.

On Wednesday evening, January 19 at 7:30 pm EDT, the RASC Toronto Centre will live stream their monthly Speakers Night meeting. This month will feature Sunna Withers, an MSc Candidate at York University. Her talk is titled High Redshift Galaxies and the Early Universe. Everyone is invited to watch the presentation live on the RASC Toronto Centre YouTube channel. Details are here.

Starting Friday afternoon, January 21 at 5 pm EST, Students for the Exploration and Development of Space (SEDS-Canada) will host a 3-day space event on the theme “To Infinity and Beyond: Innovation in Space”, covering opportunities in space and new technologies and innovations. Tickets and details are here.

RASC’s in-person sessions at the David Dunlap Observatory may not be running at the moment, but they are pleased to offer some virtual experiences instead, in partnership with Richmond Hill. The modest fee supports RASC’s education and public outreach efforts at DDO. On Sunday afternoon, January 23 from 12:30 to 1 pm EST, tune in for DDO Sunday Sungazing. Safely observe the sun with RASC, from the comfort of your home! During these family-friendly sessions, a DDO Astronomer will answer your questions about our closest star: the sun! Learn how the sun works and how it affects our home planet. Live-streamed views of the sun through small telescopes will be included, weather permitting. Only one registration per household is required. Deadline to register for this program is Wed., January 19, 2021 at 3 pm. Prior to the start of the program, registrants will be emailed the virtual program links. The registration link is here.

Don’t forget to take advantage of the astronomy-themed YouTube videos posted by RASC Toronto Centre and RASC Canada.

Keep looking up, and enjoy the sky when you do. I love questions and requests. Send me some!