A Missing Moon Lets Us Walk the Dog in Evening and Run the Messier Marathon All Night, and the Planet Parade Trades Saturn for Mercury!

This spectacular image of the Seagull Nebula or IC 2177 in northern Canis Major was captured and processed by Mohammed Srour in February, 2024. the reddish colour is ionized interstellar hydrogen located about 1825 light-years from our sun. The wings of the bird span 2.5 degrees, or five times the width of the moon. Mohammad’s image and more of his work can be seen on Reddit at https://www.reddit.com/r/astrophotography/comments/1azhtyl/the_seagull_nebula_stock_dslr/

Hello, Late-February Stargazers!

Here are your Astronomy Skylights for the week of February 23rd, 2025 by Chris Vaughan. Feel free to pass this along to your friends and send me your comments, questions, and suggested topics. You can also follow me on FaceBook, Instagram, Threads, and Bluesky as astrogeoguy! Unless otherwise noted, all times are expressed in Eastern Time. To subscribe to these emails please click this MailChimp link.

If you’d like me to bring my Digital Starlab portable inflatable planetarium to your school or other daytime or evening event in Simcoe, Grey, and Bruce Counties, or deliver a virtual session anywhere, contact me through AstroGeo.ca, and we’ll tour the Universe, or the Earth’s interior, together! My book with John A. Read entitled 110 Things to See With a Telescope is a guide to viewing the deep sky objects in the Messier List – for both beginners and seasoned astronomers. DM me to order a signed copy!

The moon will be visiting the sun and missing from the evening sky until late this week. That will allow us to attempt to view all of the objects on Charles Messier’s list of deep sky objects in an all night long marathon, or just take a casual stroll through the stars of the Canis Major (the Big Dog) on any evening. The planet parade will drop Saturn and Neptune while adding Mercury, setting up a twilight planetary conjunction on Monday evening. Read on for your Skylights!

Walking the Big Dog

Although it has to compete with the brilliant planets Venus and Jupiter this winter, the night sky’s brightest star Sirius should also catch your eye during evening at this time of the year. For those of us living at mid-northern latitudes on Earth (i.e., North America, Europe, Asia), once the sky has darkened sufficiently, say after about 7:30 pm local time, Sirius will be sparkling less than a third of the way up the southern sky. Orion (the Hunter) and his famous belt will be located to Sirius’ upper right. Sirius will reach its highest position over the southern horizon at 8:45 pm and then descend in the southwestern sky and set by 1:45 am local time.

Sirius’ name means “searing” or “scorching” in Greek. It’s also commonly known as the Dog Star and Alpha Canis Majoris (or α CMa, for short) because it is the brightest star in the constellation of Canis Major (the Big Dog). To my eyes, the constellation genuinely resembles a wiener dog, with Sirius sparkling as the dog’s collar tag! The pup’s head is formed by a triangle of medium-bright stars to Sirius’ upper left (celestial east), but those are near the limit of visibility in urban skies. Nose to tail, the constellation covers about 19°, or two fist diameters. From ears to paws, he’s about one fist diameter across. The rest of the dog’s body, composed of more easily visible stars, extends to the lower left (or celestial southeast) of Sirius. Fido is rearing up and facing west, as if he is begging Orion for a treat.

Canis Major’s location only about 20° south of the celestial equator allows it to be visible at times from everywhere on Earth except far northern latitudes. That has made the distinctive star pattern a feature of many cultures’ sky. Perhaps directed by Orion, the Big Dog is chasing Lepus (the Hare), which shines to his right (celestial west). Above (north of) the dog are the faint stars of Monoceros (the Unicorn). Observers at latitudes south of Canada can also see the constellations Puppis (the P**p Deck) and Columba (the Dove) underneath him.

In mythology, the dog was the hound Laelaps, a gift from Zeus (or Artemis, the Huntress) to Europa. He was said to always catch his prey. After passing through several owners, Laelaps was sent to hunt the enormous Teumessian Fox, which was destined to never be caught. Their interminable chase was finally ended when Zeus turned them both to stone and placed them in the sky as the constellations we now know as Canis Major and Canis Minor (the Little Dog).

In China, Sirius is called Tiān Láng 天狼, aka “the Celestial Wolf”. Many First Nations cultures saw a dog’s shape in these stars and called Sirius the Moon Dog Star (Inuit), the Wolf Star (Pawnee), and the Coyote Star.

The bright star Wezen (δ CMa), which marks the dog’s, um, “bottom” sparkles about a fist’s diameter below Sirius. Wezen, from the Arabic phrase Al Wazn “weight” is a rare, massive, yellow supergiant star. One day it will explode in a supernova. The tip of the dog’s tail, marked by a fainter star named Aludra (η CMa), is four finger widths (or 4°) to the lower left of Wezen. Two finger widths above Wezen you’ll find two less conspicuous stars positioned side-by-side and separated by two finger widths. They nicely demark the dog’s slim torso. The left-hand (celestial eastern) star is whitish Al Zara. To the right is fainter and orange-tinted Udra.

Both stars are designated Omicron Canis Majoris (o CMa). Al Zara is Omicron2 CMa. This modest point of light, 2,760 light-years away from Earth, is a massive supergiant star – one of the most luminous stars known. It radiates about 220,000 times as much visible light as the sun. Since 1943, the spectrum of Al Zara has served as one of the reference points from which other stars are classified. Udra or Omicron1 CMa is also a supergiant that has inflated and cooled. It’s about 3,500 light-years away.

If you aim binoculars or any size of telescope slightly more than double the distance from Udra to Al Zara, you’ll land on the double star designated 145 CMa and HR2764, but better known as the Winter Albireo. It will appear as a delightful coloured pair of stars – one orange and one blue – snuggled close together.

Several finger widths (or 4°) to the lower right of Wezen, a bright star named Adhara (ε CMa) represents the dog’s rear legs. (Some representations of him include two dimmer stars for the rear paws.) Adhara is a hot blue giant star with a surface temperature of a whopping 21,000 K and located about 34 light-years from the sun. It’s the brightest star in the sky when viewed in ultraviolet light, and it, too, is on its way to death by supernova. Arabic astronomers associated the stars Adhara, Aludra, Wezen, and Al Zara with the Maidens in one of their stories.

The dog’s front legs are formed by the bright star Mirzam (β CMa), which is located about a palm’s width to the right of Sirius. Mirzam, which means “the Herald” because it rises just before Sirius, is 60 times more luminous than Sirius. If that star were located where Sirius is, instead of 500 light-years away from us, it would appear 15 times brighter than Venus!

A tall triangle of stars to the left of Sirius form the dog’s head. They include the bright, blue-white, giant star Muliphein (γ CMa) marking his eye, the orange giant star Theta CMa above it that marks his nose, and the slightly fainter star Iota CMa that is closest to Sirius. Iota is a blue-white supergiant star 46,000 times more luminous than the sun and located 300 times farther away than Sirius!

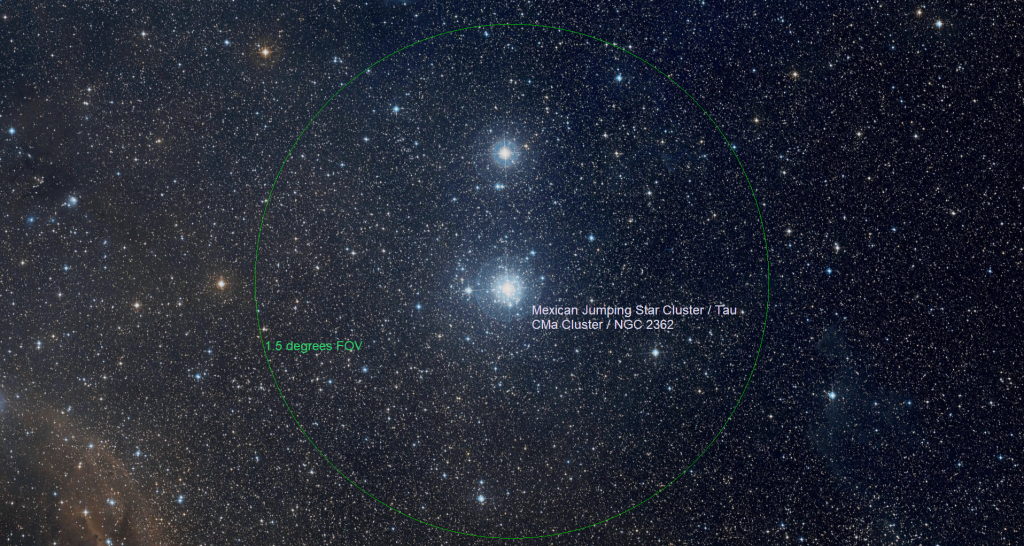

In the heart of Canis Major, about four finger widths below Sirius, is a bright little cluster of stars designated Messier 41 and the Little Beehive Cluster. Binoculars will show it easily. The cluster, which is about 2,300 light-years away from our sun, consists of several brighter golden stars and numerous fainter ones. Another nice cluster named NGC 2354 sits about 2.5 finger widths to the upper left of Wezen. An even nicer, but smaller, cluster sits three finger widths to the left (celestial east) of Wezen. It’s formally known as the Tau CMa Cluster and NGC 2362, and also the Mexican Jumping Star and Pirate’s Jewels Cluster. In a telescope, it reminded me of a sideways glittering Eiffel Tower!

A bright little nebula with an unusual shape is located almost a fist’s diameter to the upper left (or 8.8 degrees to the celestial northeast of Sirius. NGC 2359 is aglow with a mixture of reddish light from ionized hydrogen and some blue light scattered by interstellar dust. “Wings” of gas flanking the main zone have given it the nick-names Thor’s Helmet, the Duck Nebula, and the Flying eye Nebula. Scan around that area of sky with your binoculars – the winter Milky Way has populated Canis Major with many such dog treats. A long exposure image centred just a few degrees to the left of the dog’s nose star Theta CMa will reveal the large and beautiful Seagull Nebula or IC 2177.

Sirius appears so bright because it is about 25 times more luminous than our Sun, and is only a mere 8.6 light-years away from Earth. (Most stars you see are hundreds of light-years away.) Furthermore, Sirius is heading towards our sun, and will continuously brighten over the next millennia! A large, good quality telescope can show you Sirius’ tiny companion – a white dwarf star designated Sirius B, that some astronomers call the Pup. I prefer to call it the Flea! For the next several years of Sirius B’s 50-years-long orbit, it will remain far enough away from Sirius to allow us to see it more easily against the big star’s glare.

Sirius is famous for exhibiting flashes of intense colour as it twinkles. This is because northern hemisphere observers usually see the star positioned low in the sky, so that its very bright light is passing through a thicker blanket of air. The pockets of turbulence in our atmosphere that makes stars twinkle also work like tiny refracting prisms – splitting apart Sirius’ white light and randomly sending different colours (wavelengths) to our eyes.

The ancient Egyptians linked their calendar to the arrival of Sirius in the pre-dawn sky because it signaled the onset of the Nile floods around the beginning of summer. That phenomenon also gave us the expression “Dog Days of Summer” since the star was known to be crossing the daytime sky with the sun. On the next clear evening, have a look at our bright neighbour!

Messier Marathon Weekend is Coming!

Charles Messier’s list of the best and brightest showpieces in the night sky is popular with astronomers of all experience levels. During the new moon periods in early spring each year, it’s possible for lovers of deep sky objects (nebulae, galaxies, and clusters) who live anywhere on Earth between latitudes 20° south and 55° north to observe every one of the 110 objects on Messier’s list within a single night. For many amateur astronomers, this observing challenge is a bucket list item known as the Messier Marathon. This coming weekend is your first chance for 2025!

The Messier List (or catalog) objects are designated by their “M-codes”, M1 through M110 (or Messier 1 through Messier 110). Astronomers commonly refer to the group as the Messiers. Most of these famous objects also have proper names, such as the Whirlpool Galaxy (M51), the Pleiades (M45), and the Wild Duck Cluster (M11).

The objects in the list are distributed throughout the night sky visible from mid-northern latitudes. (Messier and his contemporaries observed them from Paris in the mid 18th Century.) None of the objects reside in the stars between Pisces and Aquarius, so when the sun’s trip along the ecliptic carries it between those two constellations in March every year, it allows us to see all of the Messier objects between dusk and dawn. The idea of a running a “Messier Marathon” originated in 1979 with another comet hunter, Californian Don Machholz, and others. Sadly, Don passed away in 2022. More info about him is at https://donmachholz.com/.

To see the fainter Messiers, we need a night within a day or two of the new moon, which occurs overnight this Thursday, February 27. A clear sky all night long is a must, so check the forecast and choose the night that offers the best conditions. If more than one night looks promising, make your attempt on the first night, so you have the option for a second try. This year, March 29 is a back-up date.

Pick a site free from direct lights and light pollution, with open sightlines to the horizon, especially to the west and the southeast. To improve your site selection, use a star chart, planisphere, or astronomy app to preview where the objects will be, especially the ones that will be observed when they’re near the horizon. A site at higher elevation will also give you more time to observe the low objects. Bring warm clothes, and stock up on snacks and drinks – you’ll be awake all night!

Many Messier objects are visible in binoculars – 10×50 models offer a good compromise between weight and performance. The dimmer objects will require a telescope. A 3-inch diameter (80 millimeter) telescope will work under very dark sky conditions, but a larger aperture telescope will make the job easier. Low power, wide field of view eyepieces are recommended. Be sure to set up your telescope, and organize your other equipment, well before sunset.

To start your marathon, you will need to quickly catch the objects that set in the west after sunset – specifically the dim galaxies M77 and M74. By the time the sky has grown dark enough to see these galaxies, they will be nearing the horizon. It’s a good idea to limit the time spent on the first galaxy so as not to miss the other one. Immediately after viewing those two, you’ll look for M33, the large face-on spiral galaxy in the constellation of Triangulum (the Triangle), and then the Andromeda Galaxy trio of M31, M32, and M110.

From this point, you will have time to work your way systematically across the sky from west to east. As you do so, more objects will rise in the east. By late evening, you should arrive at the Virgo Cluster of galaxies. When you have viewed the 17 objects there, you can take a break until the next group of Messiers rises into view at around 3 am local time. Here’s a website with a recommended viewing order. The objects aren’t ordered simply by their setting time, because brighter objects can be picked out during twilight, while dimmer objects need a darker sky. (Be careful not to confuse the viewing order with the Messier number.)

The final wave of objects includes M55, M75, M72, M73, and M2, which rise in the pre-dawn. The last Messier is the globular cluster M30, which will rise in the east as dawn starts to break. Observers in southerly latitudes will have an advantage because the sun rises and sets more vertically, giving them a shorter twilight period. Observers near the latitude of Toronto will not be able to see M30 this year. Several friends will join me at my local rural observatory to make the attempt this year. Fingers crossed!

Several astronomy organizations will recognize your achievement if you observe all of the Messier objects – and they don’t require you to do it in one night. The Royal Astronomical Society of Canada will issue an RASC Messier Certificate to members who complete the list and provide documentation. The society recognizes both the computerized Go-to telescope and manual approaches. The USA-based Astronomical League will send a Messier Program Certificate to members-at-large or members of affiliated astronomical societies who provide observational notes for 70 objects found without a Go-to telescope. The organization will send a lapel pin and honorary membership certificate for completing the entire list (over any time frame). Both groups’ websites have information and observing forms to download and print out.

Good luck! If you’d like more details, I’ve published additional Messier Marathon information in Space.com’s Run the ‘Messier Marathon’ to Finish This Astronomical Bucket List and SkyNews magazine’s ‘Running’ the Messier marathon. More marathon planning links include The Messier Marathon Planner by Larry McNish and Rob’s Guide to the Messier Marathon.

The Moon

The moon will give us one more week of dark evening skies worldwide, and then it will return to view after sunset in the west.

Until Thursday, our natural satellite will be approaching the sun in the eastern sky before dawn. On Monday morning, its delicate crescent will shine to the lower left (or celestial east) of the Teapot-shaped stars of Sagittarius (the Archer) while the sky is still dark, around 6 am local time.

As I was alerted to by Anton Jopko of the North Shore Erie Amateur Astronomers on FaceBook, the moon is currently near it maximum angle below (or south of) the ecliptic, placing it much lower in the sky than is usual. You might catch a glimpse of its even slimmer crescent on Tuesday and Wednesday, but then it will be competing with the already brightening sky, hiding the stars of Capricornus (the Sea-Goat) that will be hosting it.

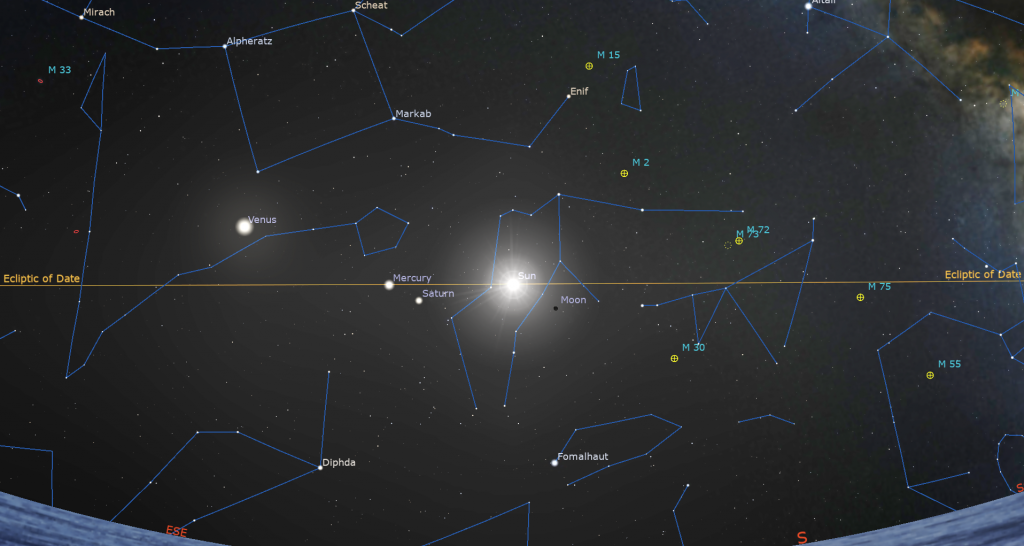

The moon will reach its new phase on Thursday, February 27 at 7:45 pm EST or 4:45 pm PST, which converts to 00:45 Greenwich Mean Time on Friday. At that time our natural satellite will be located in Aquarius (the Water-Bearer) and only 1.9 degrees south of the sun. While new, the moon is travelling between Earth and the sun. Since sunlight can only reach the far side of the moon, and the moon is in the same region of the sky as the sun, the moon becomes unobservable from anywhere on Earth for about a day. The exception to that is during a solar eclipse. A partial eclipse will happen for northeastern Canada and across the Atlantic Ocean to the UK and northwestern Europe and Africa on the morning of March 29.

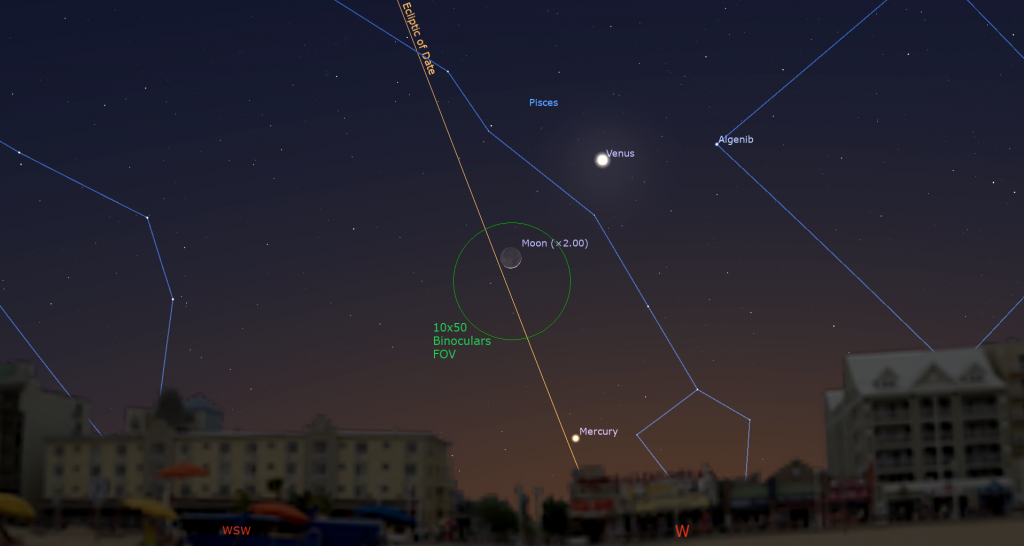

The near-vertical angle of the ecliptic, and also the moon’s orbit, after sunset at this time of year might allow some sharp-eyed observers to catch sight of the extremely thin crescent moon positioned between Saturn and Mercury on Friday after sunset. Only after the sun has completely disappeared, scan with binoculars a few finger widths above the horizon. I’ll post a simulated view of them here.

On Saturday evening, the moon’s slightly thicker crescent will shine higher, above Mercury and to the lower left of brilliant Venus in a true photo opportunity! By the time Mercury readies to set around 7:30 pm local time, the surrounding stars of Pisces (the Fishes) will start to appear.

The moon will wax fuller in phase and linger longer after sunset every night. Next Sunday night, it will pose to Venus’ upper left while still swimming among the Fishes. Watch for the distinctive grey oval of Mare Crisium “the Sea of Crises” within the moon’s lit crescent that night, kicking off the best moon-viewing period of the current lunar month.

The Planets

The rather overblown “Great Planetary Alignment” will reach its climax this week when Mercury returns to the western sky after sunset a few days before Saturn takes its final bow for 2024-25. While seven planets will all be above the horizon for a short period after sunset, only three of them will be easy for anyone to see. The other four will be either too faint or too immersed in the post-sunset haze and bright sky to be seen without your friendly neighbourhood astronomer to guide you. The planets will NOT be arranged in a uniformly-spaced line across the sky as depicted in A LOT of social media posts. Sigh.

Mercury is in the opening days of a good evening apparition (the fancy word that astronomers use for its occasional visits) that will last until about mid-March. Every day the planet will swing a little wider of the sun, causing it to linger a bit longer after sunset and climb a bit higher in the western sky. The planet is relatively bright recently, allowing you to see it with your unaided eyes and through binoculars – but only after the sun has completely set.

Meanwhile, the rest of the sky is shifting westward towards the sun every day due to Earth’s orbit around the sun. That causes objects in the west to drop lower day by day and objects in the east to climb higher day by day. That’s in addition to the “setting in the west” that everything celestial does due to Earth’s rotation. You can separate out the two effects by watching a particular star at exactly the same time of the evening over a few days and note how it drops lower with respect to the trees and rooftops night over night. To see the star in the same location, you’d need to look 4 minutes earlier each day.

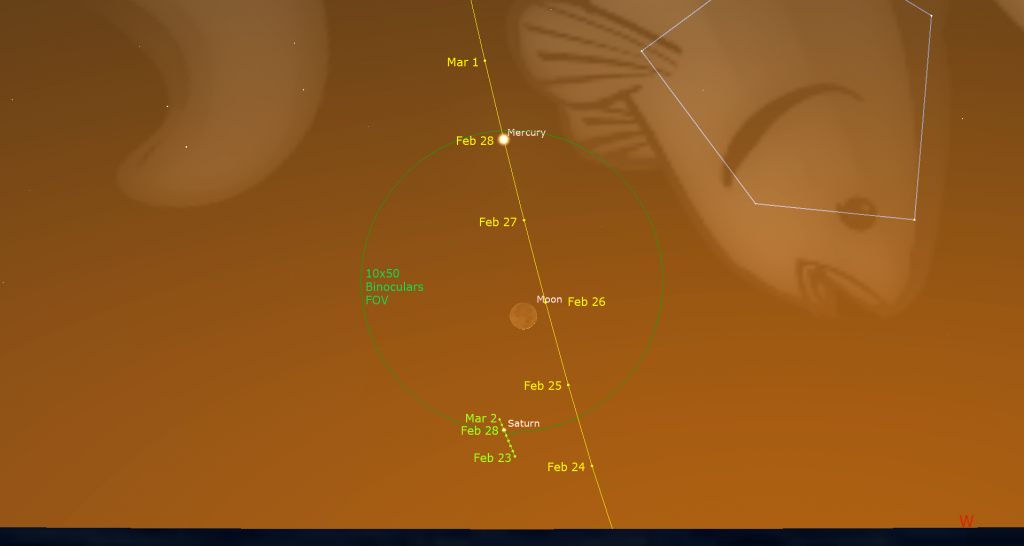

Every day, Saturn and the surrounding stars of Aquarius (the Water-Bearer) are being carried downward into the sunset while Mercury is swinging up and away from the sun, causing the two planets to pass one another in a twilight planetary conjunction on Monday. Mercury’s bright speck will start to be visible a palm’s width above the western horizon by about 6:15 pm local time. Nine times fainter Saturn will require binoculars and a darker sky. Both planets will be a bit tricky to see against the twilit sky around them and the haze above the horizon. Wait until the sun has fully disappeared before using binoculars or a telescope.

Tonight (Sunday), Mercury will be located several finger widths to the lower right (or 3° to the celestial WSW) of Saturn. Both will fit into the same view in your binoculars. On Monday, Saturn will shine a thumb’s width to Mercury’s left. On Tuesday, Saturn will be a thicker thumb’s width to Mercury’s lower left. On Wednesday and beyond, Saturn will be farther and farther below Mercury. They’ll appear in binoculars together only until Friday, when the young crescent moon will also pose between them. That’s fun!

I’m afraid that’s about it for Saturn. No one on Earth will easily see the ringed planet again until after it passes the sun at solar conjunction on March 12 and enters the eastern pre-dawn sky. That’s a shame because Saturn’s rings will almost disappear when they become aligned edge-on towards Earth in late March. For that once in every 15 years event, observers viewing Saturn from South America, South Africa, Australia and New Zealand will have the best chance to see an unadorned Saturn before sunrise for a week or so.

If you are able to see Mercury in your telescope, it will have a gibbous, rugby ball shape that wanes in illuminated phase over the week. Saturn will actually be about three times larger than Mercury.

Venus is still shining near its maximum brilliance in the western sky every evening. It will rapidly drop lower over the next few weeks, so enjoy it while you still can. Venus’ rapid departure from the sky is the combined effect of the western sky’s daily downward shift added to the planet’s own orbital motion sunward. This week Venus will drop into the trees by about 8 pm local time. To see the planet’s very slim crescent shape most clearly, wait until the sun has fully set and then aim your telescope at Venus while the sky is still bright. That way Venus will be higher, shining through less intervening air, and her glare will be lessened. Good binoculars can hint at Venus’ non-round shape, too.

Faint blue Neptune is located low in the western sky below Venus and above Mercury. Mercury’s climb will bring it a thick thumb’s width to Neptune’s right on the coming weekend, but the distant planet really isn’t observable right now, despite what the Planet Parade proponents claim.

Very bright white Jupiter and medium-bright, reddish Mars will shine high in the south even before the sky has fully darkened.

As the night wears on Jupiter will cross the western sky and then set during the wee hours. This month, Jupiter is positioned above Taurus’ brightest star, reddish Aldebaran, which marks the eye of the bull. The rest of his triangular face is composed of a group of farther-away, medium-bright whitish stars – all celestial siblings in the Hyades Cluster. They’ll be sprinkled to the lower right of Jupiter.

Another smaller, but brighter star cluster named the Pleiades, the Seven Sisters, or Messier 45 is located a fist’s diameter to the upper right of Jupiter and Aldebaran. It’s easy to see with your unaided eyes, but it looks particularly spectacular in binoculars. The distant ice giant planet Uranus is located a palm’s width to the lower right of the Pleiades this year. It will be observable from the end of evening twilight until midnight, but not easily with unaided eyes. If you use your binoculars to find the medium-bright stars named Botein and Epsilon Arietis, Uranus will be the dull-looking blue-green “star” located several finger widths to the left (or southeast of) them. In a backyard telescope, it will appear as a fairly prominent, non-twinkling blue-green dot.

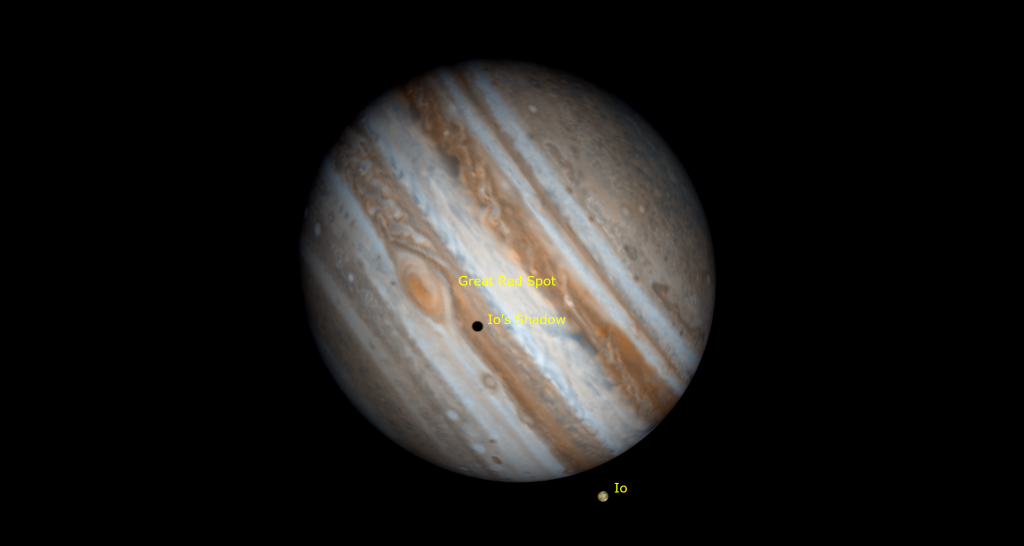

Viewed in any size of telescope, Jupiter will display a large disk striped with brownish dark belts and creamy light zones, both aligned parallel to its equator. With a better grade of optics, Jupiter’s Great Red Spot, a cyclonic storm that has raged for hundreds of years, becomes visible for several hours when it crosses the planet every 2nd or 3rd night. For observers in the Americas, that GRS will cross Jupiter’s disk during early evening on Tuesday, Thursday, and Saturday, and also after 10 pm Eastern time on Monday, Wednesday, and Saturday night. If you have any coloured filters or nebula filters for your telescope, try enhancing the spot with them.

Any size of binoculars will show you Jupiter’s four Galilean moons named Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto lined up beside the planet. Those moons complete orbits of the planet every 1.7, 3.6, 7.2, and 16.7 days, respectively. If you see fewer than four moons, then one or more of them is crossing in front of or behind Jupiter, or hiding in Jupiter’s dark shadow – or two of the moons are very close together, or one moon is eclipsing or occulting another one. All four moons will clump up on one side of Jupiter on Monday evening, and again, but spread out more, on Tuesday.

From time to time, observers with good quality telescopes can watch the black shadows of the Galilean moons travel across Jupiter’s disk. In the Americas, Io’s small shadow will lead the Great Red Spot across Jupiter on Monday evening, February 24 between 8:05 pm and 10:16 pm EST (or 01:05 to 03:16 GMT on Tuesday). Additional shadow crossings will be visible in other time zones.

Mars is the tail end of the planet parade. Its bright, reddish dot will shine high in the southeastern sky after dusk, forming a triangle to the right (or celestial southwest) of Gemini’s bright stars Pollux and Castor. Mars will be highest due south at 9:15 pm local time and set in the northwest around 5 am local time. At 123 million km away and receding every night, Mars is still close enough to Earth to show us its bright polar cap and dark patches on its small reddish globe when viewed through a quality backyard telescope – but those features are less distinct with each passing week.

Today (Sunday, February 23), Mars will cease its westward motion through the stars of northern Gemini, ending a retrograde loop that it began in early December. From now on, Mars will resume its regular easterly prograde motion by moving downwards compared to Castor and Pollux. The planet will also more rapidly fade in brightness while Earth moves farther and farther from it. We can continue to observe Mars until late July.

Evening Zodiacal Light

If you live in a mid-northern latitude location where the sky is free from light pollution, you might be able to spot a phenomenon called the zodiacal light during the two weeks that precede the new moon arriving on February 27. After the evening twilight has faded, you’ll have about half an hour to check the western sky for a broad wedge of faint light extending upwards from the horizon and centered on the ecliptic below the planets Venus and Saturn. That glow is the zodiacal light – sunlight scattered from countless small particles of material that populate the plane of our solar system. Don’t confuse it with the brighter Milky Way, which extends upwards from the northwestern evening horizon at this time of year. Pranvera Hyseni recently posted a nice photo of it on her FaceBook page here.

Eyeing Orion

If you missed last week’s tour of the eye-catching constellation of Orion (the Hunter) and his famous three-starred belt, I posted it here.

Public Astronomy-Themed Events

Every Monday evening, York University’s Allan I. Carswell Observatory runs an online star party – broadcasting views from four telescopes/cameras, answering viewer questions, and taking requests! Details are here. They host in-person viewing on the first clear Wednesday night each month. Other Wednesdays they stream views online via the observatory YouTube channel. Details are here.

On Saturday, March 1 from 7 to 9 pm EST, the in-person Astronomy Speakers Night program at the David Dunlap Observatory in Richmond Hill, Ontario will feature Benjamin Law. His talk will be Seeing Double (Stars).After the presentation, participants will view interesting celestial objects through telescopes on the lawn (weather permitting). More information and the registration link is at ActiveRH.

Keep your eye on the skies! I love getting questions and requests. Send me some!