A Sun-Hugging Moon Lets Us See Subsiding Perseids, Planets Peak Overnight, and We Fly With Eagle Aquila!

This image of the Wild Duck Cluster, also known as Messier 11 and NGC 6705, was captured by the European southern Observatory. Note the blue and yellow stars, and the odd red one. The entire photograph covers about the size of the full moon in the sky, making M11 one of the easiest-to-see Summer Milky Way objects for binoculars. (ESO Wikipedia)

Hello, mid-August Stargazers!

Here are your Astronomy Skylights for the week of August 13th, 2023 by Chris Vaughan. Feel free to pass this along to your friends and send me your comments, questions, and suggested topics. You can also follow me on Twitter as @astrogeoguy! Unless otherwise noted, all times are expressed in Eastern Time. To subscribe to these emails please click this MailChimp link.

If you’d like me to bring my Digital Starlab portable inflatable planetarium to your school or other daytime or evening event, or deliver a session online, contact me through AstroGeo.ca, and we’ll tour the Universe, or the Earth’s interior, together! My terrific book with John A. Read entitled 110 Things to See With a Telescope is a guide to viewing the deep sky objects in the Messier List – for both beginners and seasoned astronomers. DM me to order a signed copy!

The moon will largely remain out of sight this week while it passes the sun, only returning as a thin crescent in the western, post-sunset sky starting next weekend. The intervening moonless nights will be ideal for catching leftover Perseids meteors and for touring the summer Milky Way, so I highlight the sights in Aquila (the Eagle). The bright gas giant planets and their fainter ice giant companions Neptune and Uranus rise late and shine overnight until dawn. Read on for your Skylights!

Perseids Meteor Shower

The annual Perseids Meteor Shower, which happens when Earth travels through debris ejected from a periodic comet named 109P/Swift-Tuttle, peaked this morning (Sunday), will taper off between now and September 1. There will be less morning moonlight to interfere its “shooting stars” this week. I shared viewing tips and posted some nice Perseids photos here last week. Good luck!

The Moon

The moon will be out of the evening and overnight sky again this week while it passes the sun, allowing us to see more of the Perseids meteors as they taper off. Meteor-watchers who are outside in the hours before dawn on Monday can see the pretty sight of the old crescent moon in Cancer (the Crab) after it rises in the east around 4 am local time. Gemini’s brightest stars Pollux and Castor will shine above the moon until the brightening sky hides them. On Tuesday morning, the razor-thin moon will still be travelling through the Crab, but effectively out of sight in the pre-sunrise twilight.

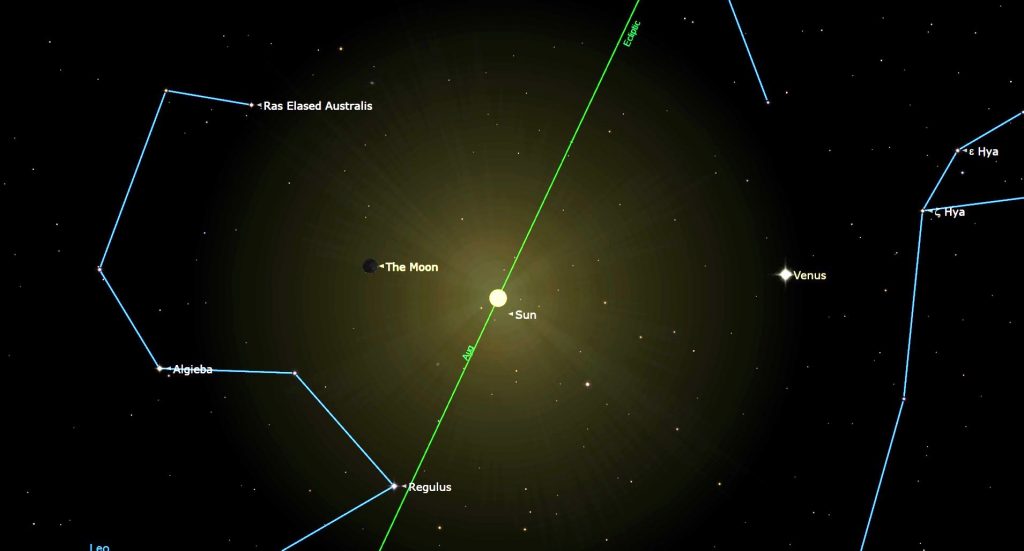

On Wednesday at 5:38 am EDT, 2:38 am PDT, or 09:38 Greenwich Mean Time, the moon will officially reach its new moon phase. At that time our natural satellite will be located in Leo (the Lion), 4.3 degrees northeast of the sun. While new, the moon is travelling in the space between Earth and the sun. Since sunlight can only touch the far side of the moon, and the moon’s unlit Earth-facing side is in the same region of the sky as the bright sun, our natural satellite becomes completely hidden from view from anywhere on Earth for about a day. Only if there’s a solar eclipse, as there will be on October 14, can we see a new moon.

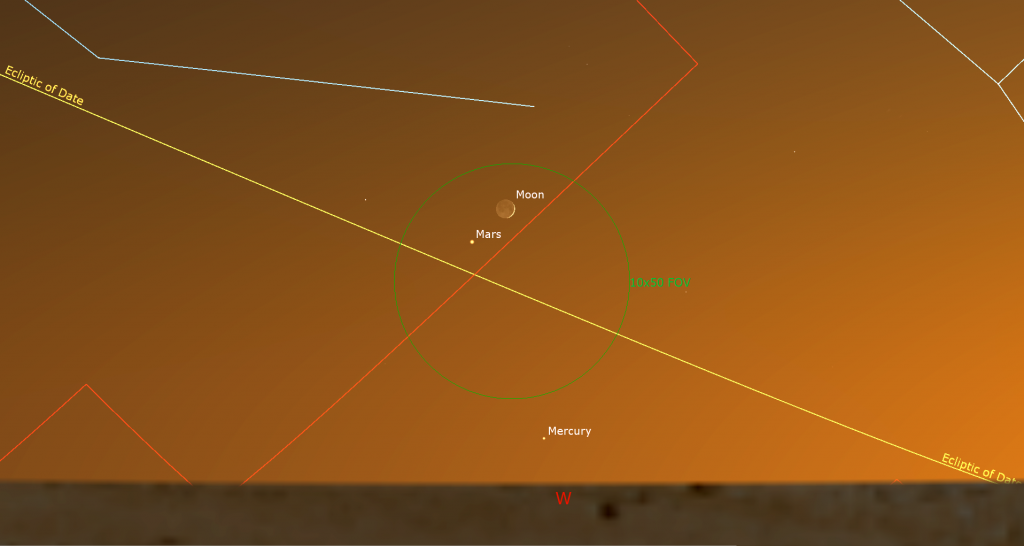

The young crescent moon, still in Leo, will join the western evening sky on Thursday – but its thin crescent will be far too close to the sun to be visible unless you live near the tropics. The moon will be much easier to spot on Friday. After the sun has completely set, use binoculars to scan the western sky above the horizon. For mid-northern latitude skywatchers, the moon will be positioned about a thumb’s width to the upper right (or 1.4 degrees to the celestial north) of Mars’ faint speck – close enough for them to share the view in binoculars. Mercury, which will shine nearly three times brighter than Mars, might be visible a palm’s width below the moon and Mars. Initially, all three objects will be surrounded by twilight, but the Moon and Mars should become easier to see in a darker sky shortly before they set after 9 pm local time. Observers at lower latitudes will see the trio more easily in a darker sky.

The moon will wax fuller and set about half and hour later each evening. On Saturday, its pretty crescent will be joined by the stars of Virgo (the Maiden) once the sky darkens enough. The moon will end the week posing a palm’s width to the right (or 6° to the celestial northwest) of the Maiden’s brightest star Spica next Sunday evening. Grab your binoculars or a backyard telescope and take a look at the waxing moon. Keep them handy, though – next week will be even better.

The Planets

We’re stuck in a transition period for planet-gazing. Mercury and Mars are lurking above the western horizon after sunset each night for another week or so, but they will be very difficult to see unless you live at tropical latitudes. Saturn will be shining in late evening, and Jupiter after midnight – but Venus is hidden near the sun. Since Saturn and Jupiter are rising about half an hour earlier each week, and Venus will be breaking free of the morning twilight soon, our prime time to see the planets will be September through January.

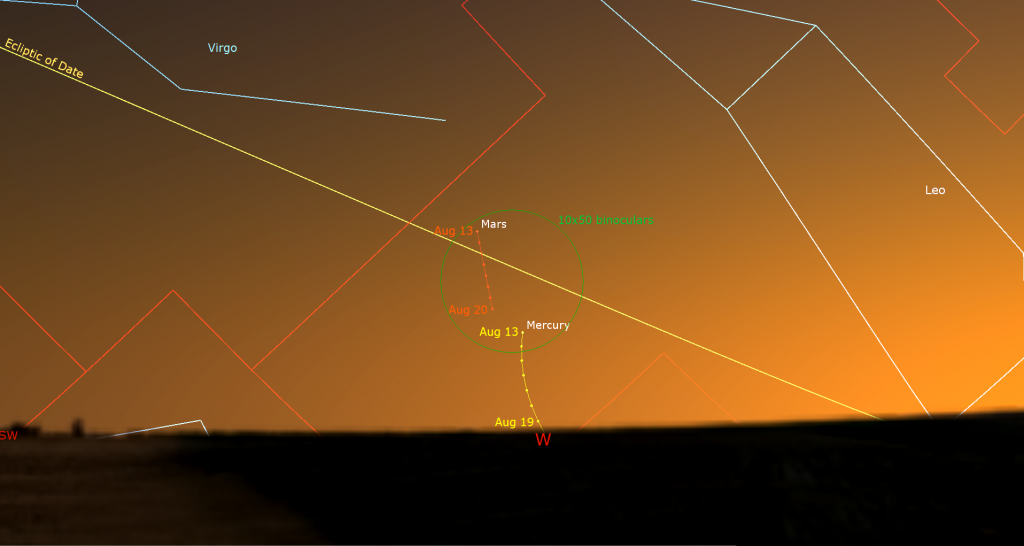

This week, if you have an unobstructed view towards the western horizon, and haze-free skies, you can seek out the medium-bright dot of Mercury just above the horizon after sunset. It’ll be sinking lower with each passing day, however, so you’ll only have a few minutes around 9 pm local time to see it.

Much fainter Mars will start this week positioned a few finger widths to Mercury’s upper left, their minimum separation. By next week, Mercury will drop to a palm’s width below Mars. The young crescent moon will shine a fist’s diameter to the right of the two planets on Thursday, and just to Mars’ upper right on Friday. While Mercury descends through Leo (the Lion), Mars’ easterly motion will see it step over the border from Leo into Virgo (the Maiden) on Thursday. Mars will set at about 9:30 pm local time at mid-northern latitudes.

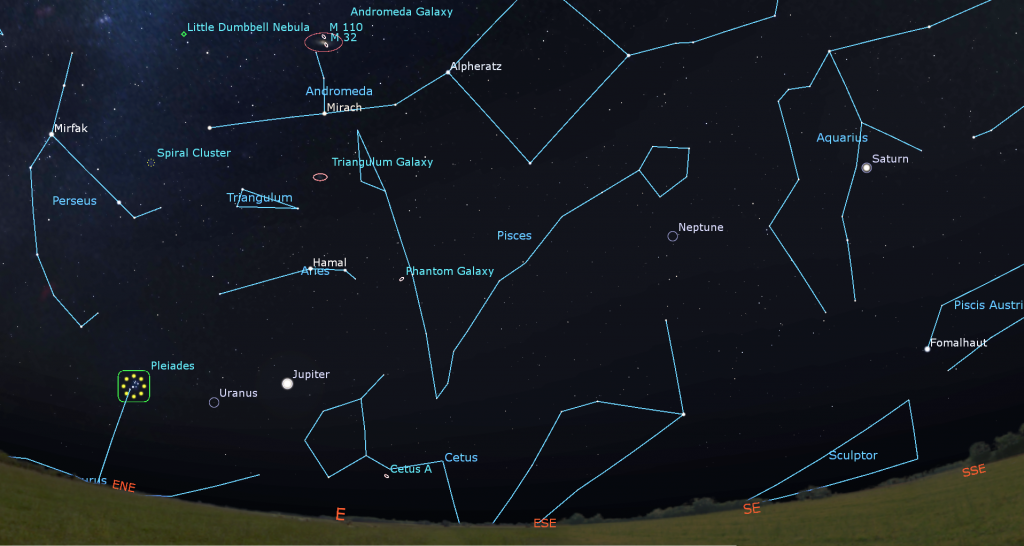

By the time Mercury and Mars are setting, the much brighter, yellowish dot of Saturn will be shining over the east-southeastern horizon. It’ll climb high enough to clear the rooftops by about 10 pm – but you’ll get the clearest views of Saturn in a telescope between 11:30 pm and 5 am. If you head outside by then, you’ll still be able to see the stars of Aquarius (the Water-Bearer) shining around Saturn, and the bright trio of the Summer Triangle asterism stars getting ready to set well off to Saturn’s upper right. The very bright star Fomalhaut (or Alpha Piscis Austrini, the Southern Fish) will shine two fist diameters below Saturn during this year.

Saturn’s beautiful rings are visible in any size of telescope. If your optics are of good quality and the air is steady, try to see the Cassini Division, a narrow gap curving between the outer and inner rings, and a faint belt of dark clouds that encircle the planet’s globe. Remember to take long, lingering looks through the eyepiece – so that you can catch moments of perfect atmospheric clarity. Good binoculars can hint at Saturn’s rings, too.

From here on Earth, Saturn’s axial tilt of 26.7° lets us see the top of its ring plane, and allows its brighter moons to array themselves above, below, and alongside the planet. Saturn’s largest and brightest moon Titan never wanders more than five times the width of Saturn’s rings from the planet. The much fainter moon named Iapetus can stray up to twelve times the ring width during its 80-day orbit of Saturn. The next brightest moons Rhea, Dione, Tethys, Enceladus, and Mimas all stay within one ring-width of Saturn.

During this week, Titan will migrate counter-clockwise around Saturn, moving from just to the planet’s lower left (celestial east) tonight (Sunday) to Saturn’s upper right (celestial west-northwest) next Sunday night. (Remember that your telescope will probably flip the view around.) How many of the moons can you see in your telescope? You may be surprised at how many you can see if you look closely. Saturn will be available for our evening viewing pleasure through its opposition in late August and then on until mid-winter! This summer the blue ice giant planet Neptune, currently 840 times fainter than Saturn, will be lurking two fist diameters to Saturn’s left, or 22° to its celestial northeast.

Brilliant, white Jupiter, which currently shines about 15 times brighter than Saturn, will rise around 11:30 pm local time this week. This year Hamal and Sheratan, the brightest stars of Aries (the Ram), will shine a generous fist’s diameter above the giant planet. Jupiter might catch your eye while it gleams high in the southern sky before sunrise.

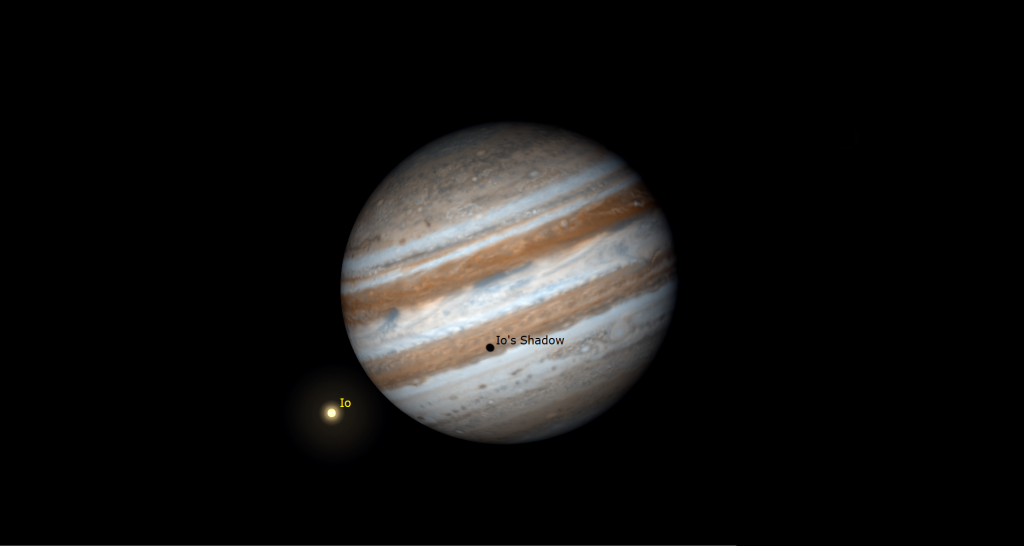

Binoculars will show you Jupiter’s four Galilean moons in a line beside the planet. Named Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto in order of their orbital distance from Jupiter, those moons complete orbits of the planet every 1.7, 3.6, 7.2, and 16.7 days, respectively. If you see fewer than four moons, then one or more of them is crossing in front of or behind Jupiter, or hiding in Jupiter’s dark shadow – or two of the moons are very close together or occulting one another. All four of them will huddle to the west of Jupiter next Sunday night.

Jupiter will climb high enough for good telescope views after about 1 am local time. It’ll look even better from then until dawn. Even a small, but decent quality telescope can show you Jupiter’s dark belts and light zones, which are aligned parallel to its equator. With a better grade of optics, Jupiter’s Great Red Spot, a cyclonic storm that has raged for hundreds of years, becomes visible for several hours when it crosses the planet every 2nd or 3rd night. For observers in the Americas, that GRS will cross Jupiter’s disk on early on Wednesday and Friday morning, and before dawn on Tuesday, Thursday and next Sunday morning. If you have any coloured filters or nebula filters for your telescope, try enhancing the spot with them.

From time to time, the small, round, black shadows cast by Jupiter’s Galilean moons become visible in amateur telescopes when they cross (or transit) the planet’s disk. On Monday morning, August 14, Europa’s small shadow will cross Jupiter’s southern hemisphere from 3:28 to 5:43 am EDT (or 07:28 to 09:43 GMT). On Saturday morning, August 19, Io’s small shadow will cross Jupiter’s equatorial region from 3:05 to 5:09 am EDT (or 07:05 to 09:09 GMT).

The blue-green ice giant planet Uranus will be following Jupiter across the sky this year. This week it will be located less than a fist’s diameter to the bright planet’s lower left (or 8.2° to the celestial east). The bright little Pleiades Star Cluster will be located a similar distance to Uranus’ left. Magnitude 5.8 Uranus is visible in binoculars and small telescopes if you know where to look. I’ll get more specific in the coming weeks when it will climb higher.

Aquila the Eagle

Look halfway up the southern sky on mid-August evenings, and you’ll easily spot the bright, white star Altair sitting at the bottom corner of the Summer Triangle asterism below very bright Vega and almost-as-bright Deneb. Altair is the brightest star in the venerable constellation of Aquila (the Eagle) and marks the great bird’s head. The eagle’s body and tail extend downwards to the right (or celestial southwest), more or less following the Milky Way. The wings extend upwards and downwards.

The great bird’s location close to the Milky Way has populated it with rich star fields. The celestial equator passes through it – allowing it to be seen easily by both Northern and Southern Hemisphere skywatchers. On the right (west) it is bordered by Scutum (the Shield), Serpens Cauda (the Snake’s Tail), and Ophiuchus (the Serpent-Bearer). Sagittarius (the Archer) and Capricornus (the Sea-Goat) are below it (south), and cute little Delphinus (the Dolphin) and Sagitta (the Arrow) above (north). A section of Hercules (the Hero) touches the eagle’s northern wingtip. In area, the bird spans three fist diameters square, or 30° by 30°, but the bright stars only cover about 20°, from head to tail and wing tip to tip.

Aquila so clearly resembles a bird that many cultures saw the same pattern in its stars, including the Babylonians. In Greek mythology, it was the eagle that held Zeus’ thunderbolts. The Romans called it Vultur volans “the flying vulture”. The Hindus associated the stars with the half eagle-half human god Garuda.

Classic Chinese poetry told a well-known story about the Weaver Girl and the Cowherd, one of their four great folktales. In the story, Zhī Nǚ (织女) the weaver girl was in love with Niú Láng (牛郎) the cowherd. To prevent their forbidden love, they were banished to the heavens. Zhi Nu, represented by the nearby bright star Vega, and Niu Lan, represented by Altair, were separated by the Silver River, i.e., the Milky Way. The two small stars which are visible just above and below Altair represent their children. As the story goes, each year on the 7th day of the 7th month in the Chinese lunisolar calendar, a flock of magpies would form a bridge, reuniting the lovers for one night only. In some years, the lunisolar calendar begins at the end of January, putting their 7th month into August. I suspect that those magpies were actually Perseids meteors, which travel parallel to the Milky Way every August.

The name Altair arises from the Arabic expression for “flying eagle”. The star itself is warm-white and of spectral class A7Vn, about ten times larger than our sun. It’s a mere 17 light-years away, making it the twelfth brightest star in the night sky worldwide. Altair’s 10-hour rotation rate is one of the fastest known for stars, spinning so rapidly that the star has an oblate shape (wider at the equator than it is tall). In the sky, Altair is symmetrically flanked by two small stars named Alshain and Tarazed, or β and γ Aquilae, respectively. Because the three stars resemble a weighing balance, their names are derived from the Arabic phrase for one: “shahin-i tarazu”.

The trio spans about three finger widths, or 5° of sky. Higher (more northerly) and brighter Tarazed is interesting. This orange, K3II-class star is 395 light-years-away. It is young, but highly evolved – already burning core helium, and it emits almost 3,000 times the luminosity of our sun. It also emits an abundance of X-rays! Magnitude 3.7 Alshain is located two finger widths below (or 2.7° south-southeast of) Altair. This 44.7 light-years-away, yellowish G8IV-class star has also exhausted its core hydrogen and is evolving into a giant star.

The rest of Aquila’s main stars are fainter, but nonetheless visible to unaided eyes under a dark sky. Almost a fist’s diameter to the lower right (southwest) of Altair is the star Delta Aquilae, or Almizan I, representing the eagle’s body. The wings, each a generous fist’s diameter (11°) in length, extend up and down from that star. The upper wingtip is marked by the white star Deneb al Okab Australis, or Zeta Aquilae, and a slightly dimmer star named Deneb al Okab Borealis. Those names mean the southern and northern “tail of the eagle”. (The reference to the tail arose by using a different interpretation of the star patterns.)

The lower wing is formed by two widely spaced stars. Almizan II is at the elbow, and Almizan III is at the wingtip. (Some apps use the designations Eta Aquilae and Theta Aquilae, respectively.) The eagle’s tail is marked by a pair of small stars separated by a finger’s width. The brighter tail star is named Al Thalimain Prior “the front ostrich”. The Pioneer 11 spacecraft, launched in 1973, is coasting towards this star, with an arrival time in about 4 million years! The “rear ostrich” is the star Al Thalimain Posterior or Iota Aquilae, which sits above and between the tail and the lower wingtip. Those names appear to be left-over from a previous version of the constellation.

Almizan II, the lower elbow star, is a Cepheid variable star that doubles in visible brightness from magnitude 3.5 to 4.4 on a 7.18 day cycle. At maximum, it shines almost as brightly as Lambda Aquilae, the tail of the eagle. At minimum, it’s as faint as Iota Aquilae, the “rear ostrich”. Try comparing the brightness of those three stars on different nights and see the difference!

Sweep your binoculars though the area around and above Aquila to see an abundance of stars from the nearby galactic plane, and a dark dust lane. About three finger widths to the right (or 4° WSW) of the eagle’s tail, in the next-door constellation Scutum (the Shield), you’ll easily spot another avian object – the Wild Duck Cluster or Messier 11 – a famous bright open cluster.

Within a binoculars’ field of view to the lower right of Okab are two more open star clusters named NGC 6738 and NGC 6709. Another binoculars’ field diameter to their lower right is a bigger, brighter cluster called the Tweedledee Cluster, or Graff’s Cluster, which is in Serpens. Staying within Aquila, another pair of open star clusters can be found between Almizan I and the bright star Alya (Theta Serpentis) that shines to its right. The clusters are NGC 6755 and smaller NGC 6756, sometimes called the Possible Binary Clusters.

If you have a large telescope, or if you are observing Aquila under dark, rural skies, aim your telescope a few finger widths along the eagle’s upper wing and look at the round planetary nebula named the Snowglobe Nebula or Ghost of the Moon Nebula (or NGC 6781). It’s not very bright, but it’s huge – more than twice as large as Jupiter! Once done, sweep the sky 4.5° to the lower right (or celestial southwest) of Almizan I and look for the small fuzzy patches of the globular star clusters designated NGC 6749 and NGC 6760.

More little deep sky gems are sprinkled onto the eagle. Let me know your search goes.

A Look at Lyra

If you missed last week’s look at the constellation of Lyra (the Harp), I posted it here.

Public Astronomy-Themed Events

Every Monday evening, York University’s Allan I. Carswell Observatory runs an online star party – broadcasting views from four telescopes/cameras, answering viewer questions, and taking requests! Details are here. They host in-person viewing on the first clear Wednesday night each month. Other Wednesdays they stream views online via the observatory YouTube channel. Details are here.

My free, family-friendly Insider’s Guide to the Galaxy webcast with RASC National returns on Tuesday, August 29 at 3:30 pm EST. The Insider’s Guide to the Galaxy team will head to York University’s Allan I. Carswell Observatory for a live tour and chat about York U’s astronomy program and outreach activities. We’ll end the show by highlighting our final batch of RASC Finest NGC objects. You can find more details and the schedule of future sessions here.

Space Station Flyovers

The ISS (or International Space Station) will not be visible over the Greater Toronto Area this week. Morning appearances commence next week.

Keep looking up, and enjoy the sky when you do. I love questions and requests. Send me some!