All Planets Apparent, Maori Matariki, the Moon in Morning, and Hercules on High!

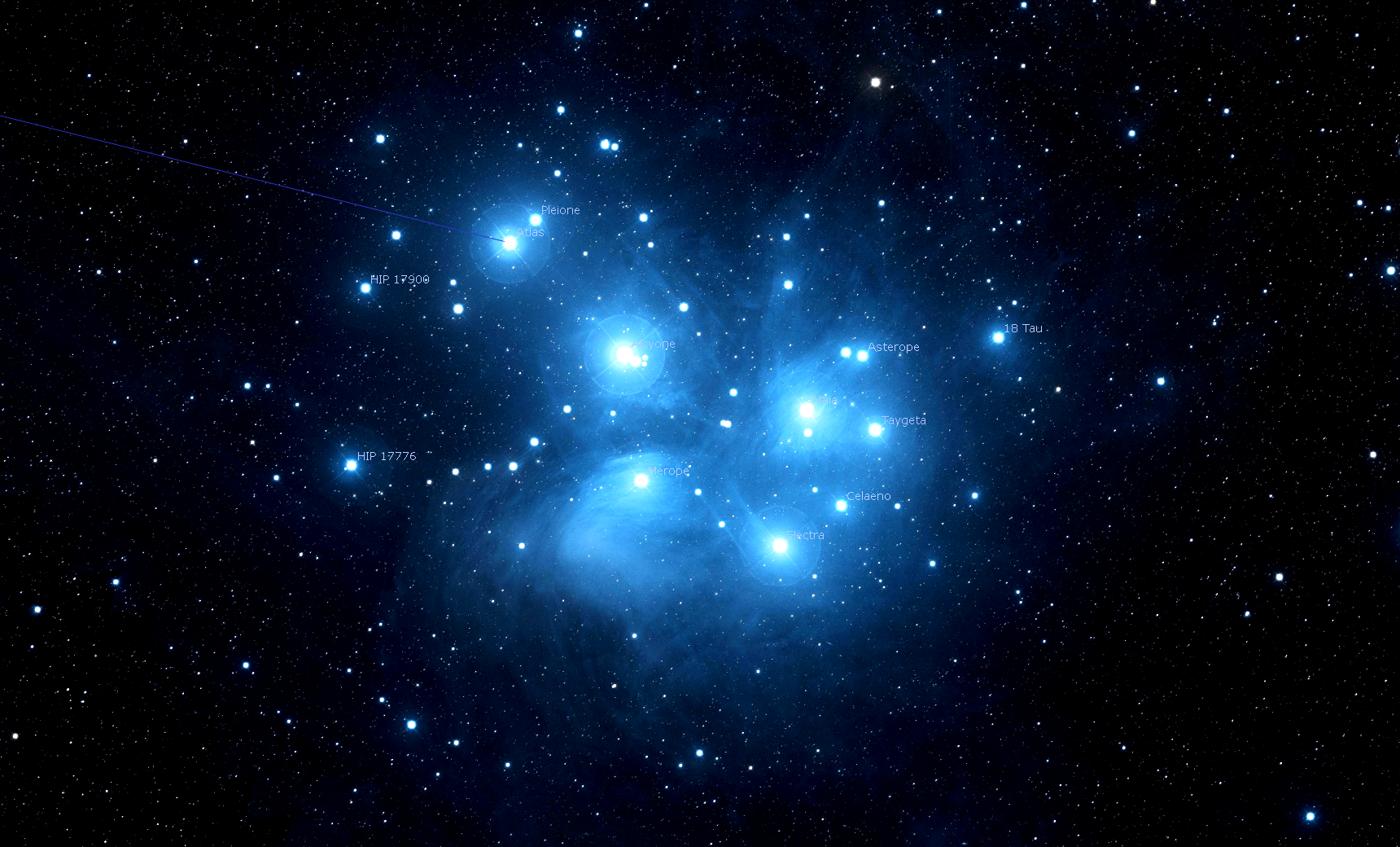

The well-known Pleiades open star cluster (Messier 45) has long been the centre of indigenous star stories around the world, including South Pacific island groups. The Maori of New Zealand tie their new year to the appearance of the Pleiades in the pre-dawn sky during June/July. The area of sky shown here spans 2 degrees.

Hello, Canada Day Stargazers!

Here are your Astronomy Skylights for the week of June 27th, 2021 by Chris Vaughan. Feel free to pass this along to your friends and send me your comments, questions, and suggested topics. You can also follow me on Twitter as @astrogeoguy! Unless otherwise noted, all times are expressed in Eastern Time. To subscribe to these emails please click this MailChimp link.

I can bring my Digital Starlab portable inflatable planetarium to your school or other daytime or evening event, or teach a session online. Contact me through AstroGeo.ca, and we’ll tour the Universe, or the Earth’s interior, together!

This week, the moon will be waning in the post-midnight sky all around the world. In the western sky after sunset dim Mars and brilliant Venus draw closer together, and Mercury’s arrival before dawn will allow all the planets to be observed between dusk and dawn! The dark, moonless sky will be ideal for viewing the sights in Hercules overhead. Read on for your Skylights!

It’s Matariki!

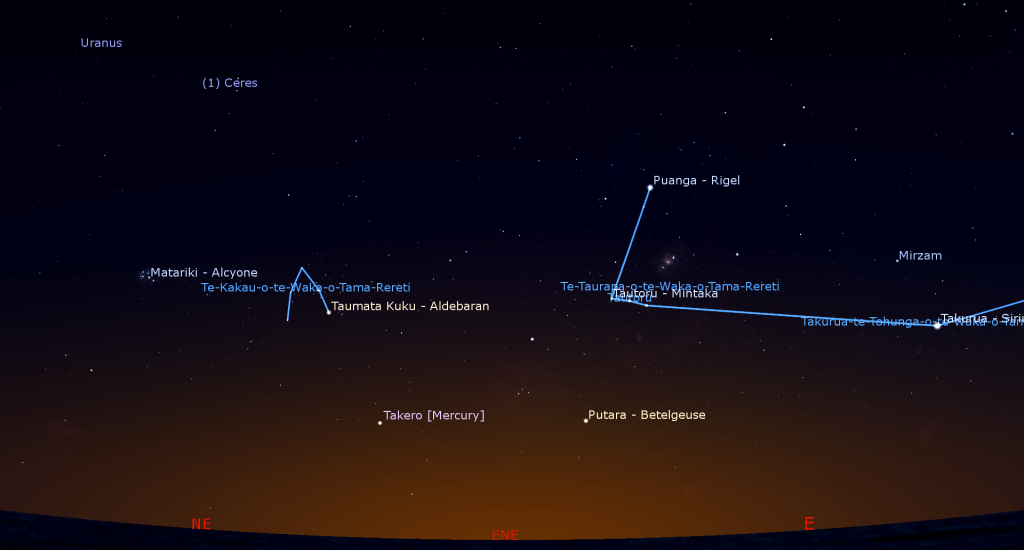

Matariki is the Māori name for the Pleiades star cluster in Taurus (the Bull). At this time of year, Taurus rises long enough before sunrise for the cluster to become visible low in the eastern sky after several months of absence from the sky. Matariki’s return to sight during Pipiri (June/July) marks the beginning of the Māori new year. This year, Matariki begins on July 2. Some groups opt to use the return of the bright star Puanga, better known as Rigel in Orion (the Hunter), instead. In 2022, Matariki will become a national holiday in New Zealand – because of astronomy!

The word Matariki is an abbreviation of Ngā Mata o te Ariki, “Eyes of God” – referring to Tāwhirimātea, the god of the wind and weather. In the Maori story of creation, Tāne Mahuta, the god of the forest, separated his parents Ranginui and Papatūānuku. His upset brother Tāwhirimātea tore out his eyes, crushed them into pieces, and threw them into the sky as stars.

Traditionally, Maori communities, or iwi, would gather together at night during a time of the constellation’s prominence, making use of the period between harvests to celebrate and make offerings for a bountiful future.

Traditions hold that the visual appearance of the Pleiades cluster was said to predict the success of the season ahead. Clear, bright stars are a good omen, and hazy stars predict that the rest of winter during July-August will be cold and harsh. The brightness of each individual star predicts the fortunes of a specific thing that star represents, such as the wind, or food that grows in trees.

The Moon

This will be the first of two consecutive weeks when the moon will be out of the evening skies the world over – perfect conditions for seeing the delights at night! For those who prefer the moon’s company, take heart – you can see Selene by getting up before sunrise, or by casting an eye to the daytime sky before mid-day!

Normally, the moon rises almost an hour later each night. But, because the angle is very acute between the ecliptic (and the moon’s orbit) and the eastern horizon at this time of year, the moon’s location change in the sky is much more right-to-left than up-to-down – so moonrise is only delayed by about 20-25 minutes from one night to the next.

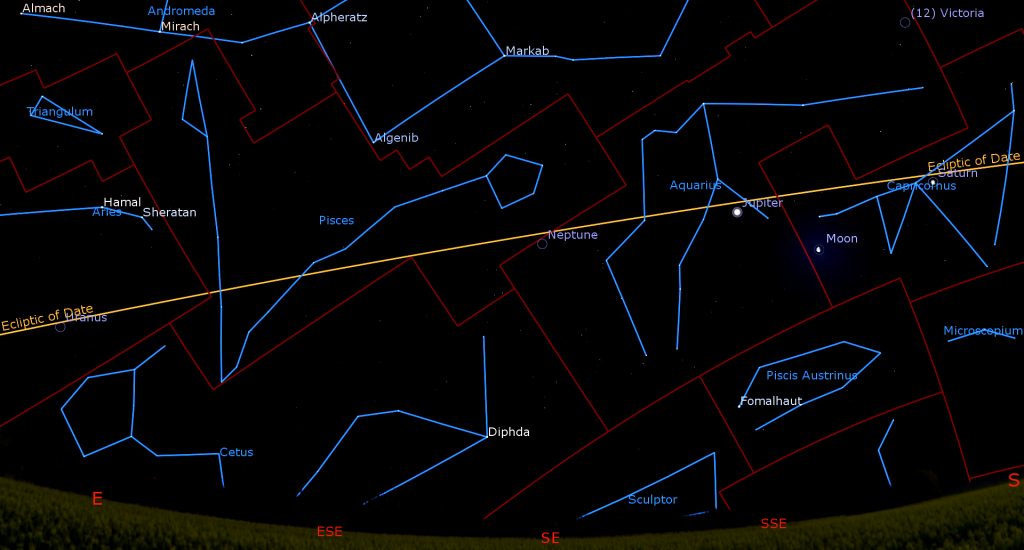

Today (Sunday) the waning gibbous moon will rise at about midnight local time. When it does, it will be making its monthly visit with the gas giant planets! The bright moon will be positioned in Capricornus (the Sea-Goat), below and between bright Jupiter on the left (or celestial east) and fainter Saturn on the right (or celestial west). The trio will make a gorgeous wide field photograph when composed with some interesting landscape scenery! On Tuesday morning the moon will slide to the east to sit under Jupiter in Aquarius (the Water-Bearer). (The trio will meet again in the evening sky on July 24, and monthly thereafter.)

From Wednesday morning to Saturday morning, the waning crescent moon will wade through the water constellations of Pisces (the Fishes) and Cetus (the Whale). The moon will officially reach its third quarter phase at 5:10 pm EDT (or 21:10 Greenwich Mean Time) on Thursday, July 1. The name for this phase refers not to the moon’s appearance – half-illuminated, on its western side, towards the pre-dawn sun – but to the fact that it has completed three quarters of its orbit around Earth, measuring from the previous new moon.

Finally, the crescent moon will end this week by rising in southern Aries (the Ram) next Sunday morning. That moon will be positioned a slim palm’s width to the lower right (or 5 degrees to the celestial southwest) of the magnitude 5.8 planet Uranus – close enough for them to share the view through binoculars. Try to find the planet before about 4:30 am local time. After that, the brightening dawn sky will overwhelm it, but will leave the moon visible. (And don’t fret if you’re not an early bird. Uranus will start to rise in the evening in early August, and the moon will visit it on August 1 and 28.)

The Planets

By the end of this week, it will be possible to see all of the planets between sunset and sunrise!

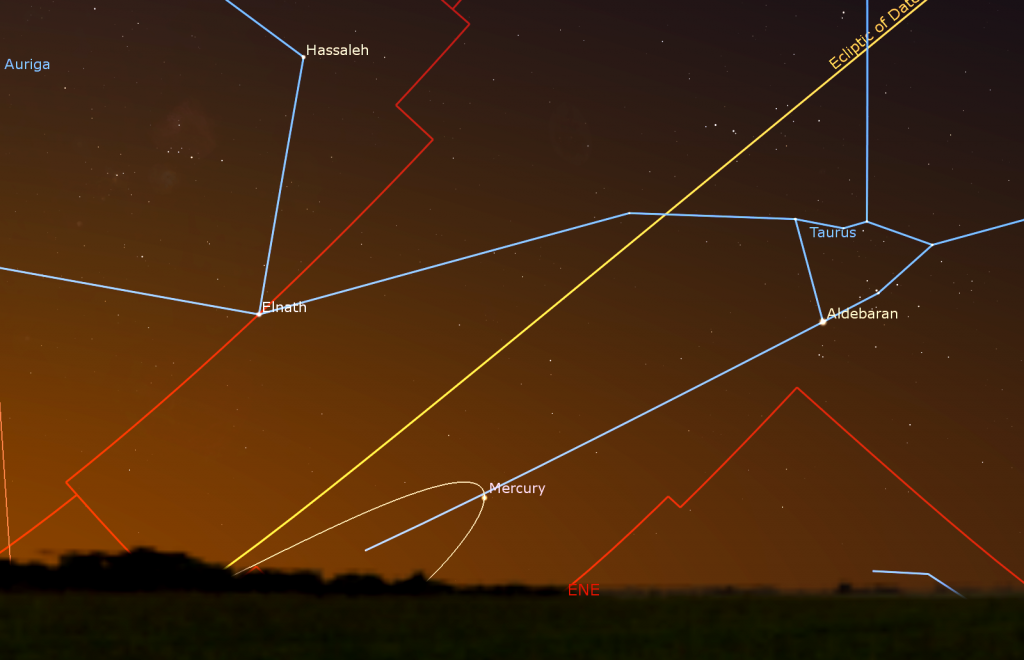

Mercury will spend all of July in the eastern pre-dawn sky. Its position below (or to the celestial south of) the dawn ecliptic will prevent Mercury from rising very long before the sun – making this apparition a poor one for Northern Hemisphere observers, but a good one for people viewing the planet from south of the equator. Mercury will reach greatest western elongation and peak visibility on Sunday, July 4, when it will stretch to 21.6° away from the sun. At mid-northern latitudes this week, the best time to see Mercury will be at about 4:45 am local time – but it will sit extremely low over the east-northeastern horizon.

You can use the very bright star Aldebaran, which marks Taurus, the Bull’s eye, to help you find Mercury. Somewhat brighter Mercury will be located a fist’s diameter to Aldebaran’s lower left. Viewed in a telescope (but only before the sun comes up) this week, the speedy planet will wax in illuminated phase from a squashed 22%-lit crescent on Monday morning to 36%-illuminated next Sunday. Meanwhile the planet’s apparent disk diameter of 9.4 arc-seconds, and its brightness, will be increasing all month long.

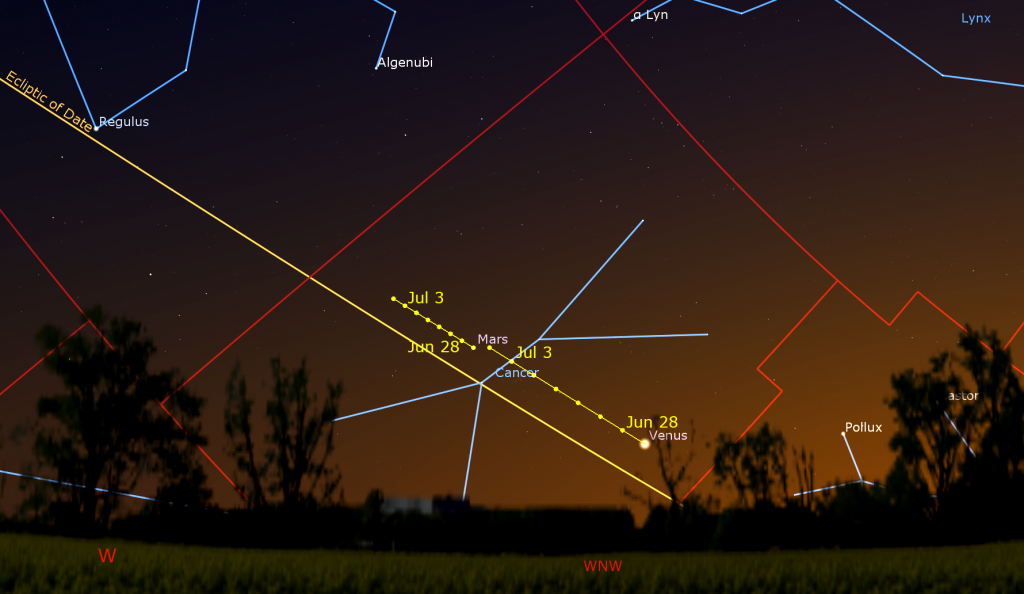

The upcoming conjunction between Venus and Mars among the stars of Cancer (the Crab) will start to become apparent this week. Tonight (Sunday), extremely bright, white Venus will pop out of the darkening sky, a little to the left of where the sun went down, at about 9:30 pm local time. If you have an unobstructed view toward the west-northwest, you can see the planet’s brilliant speck of light sitting less than a fist’s diameter above the horizon, and then descend until it sets at about 10:40 pm local time. Its setting time barely changes night after night because Venus’ eastward orbital motion is counter-acting the westward motion of the sky produced by Earth’s orbit of the sun.

Right now Venus is on the far side of the sun from Earth. That, plus its angle of 25° east of the sun, are combining to make the planet look smaller than average and only 90% illuminated – producing a slightly squashed shape in your telescope. Aim your telescope at Venus as soon as you can find the planet. That way, it will be higher, and shining through less distorting atmosphere. Ensure that the sun has completely disappeared first!

The sky will need to get much darker before the faint reddish dot of Mars appears in the west. At magnitude +1.82, Mars is nearly 200 times fainter than magnitude -3.85 Venus! Tonight Mars will be positioned less than a fist’s diameter to Venus’ upper right (or 9 degrees to the celestial east). By next Sunday that separation will be reduced almost by half. While both Venus and Mars are travelling eastward along the ecliptic, slower Mars is not able to offset the westward migration of the sky, while Venus can – so they appear to be traveling towards one another. On July 12-13, Venus will overtake and pass Mars, leaving Venus to shine as the “Evening Star” all year long while Mars disappears into the sunset and solar conjunction. For now, you can see Mars until it sets at about 11 pm local time.

This week, yellow-tinted, magnitude 0.4 Saturn will rise within the stars of central Capricornus (the Sea-Goat) just before 11 pm local time and then linger to shine in the southwestern sky before dawn. It will be chased across the sky by 16 times brighter Jupiter. Each night, Saturn’s westerly retrograde motion is increasing its distance from a medium-bright star to its lower left (east) named Theta Capricorni. If you get up early, or stay up late, to see the gas giant planets, watch for the Milky Way and the teapot-shaped stars of Sagittarius (the Archer) sitting several fist diameters off to Saturn’s right (celestial west).

Even a small telescope will show Saturn’s rings and several of its brighter moons – especially its largest moon, Titan! Because Saturn’s axis of rotation is tipped about 27° from its orbital plane (a bit more than Earth’s tilt), we can see the top surface of its rings, and its moons can arrange themselves above, below, or to either side of the planet. During this week, Titan will migrate counter-clockwise around Saturn, moving from the upper right (west) of Saturn on Sunday night to the lower left (celestial east) of the planet next Sunday. (Remember that your telescope will probably flip the view around.)

This week Jupiter will join Saturn in late evening, and beyond. Alternatively, early risers can see it in the southern sky until almost sunrise! The very bright, white, magnitude -2.6 planet is now moving slowly westward across the distant stars of central Aquarius (the Water-Bearer), a parallax effect produced when Earth, on a faster orbit, passes Jupiter on the “inside track” around the sun.

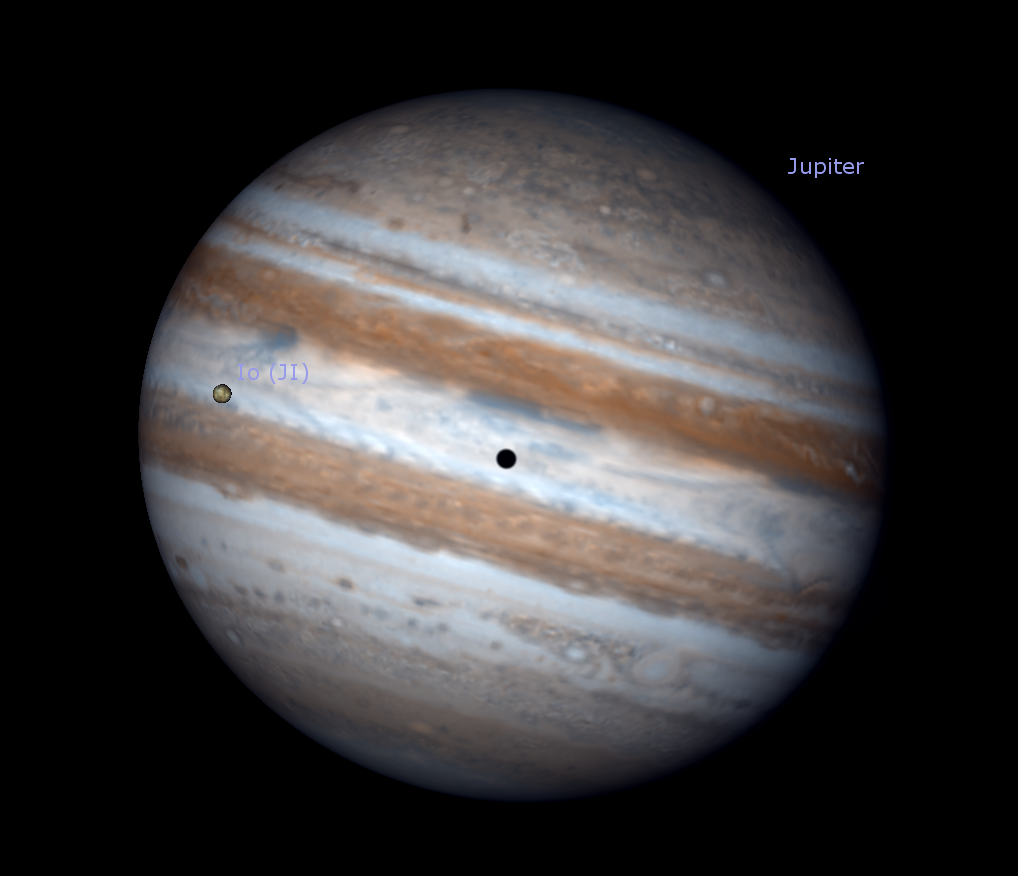

For Eastern Time Zone observers the Great Red Spot (or GRS) will be visible crossing Jupiter during the wee hours of Wednesday and Friday, and before dawn on Tuesday and Sunday morning. From time to time, the small round black shadows cast by Jupiter’s four Galilean moons become visible in amateur telescopes when they cross (or transit) the planet’s disk. On Saturday morning from 3 am to 5:15 am EDT (or 07:00 to 09:15 GMT) Io’s small shadow will cross Jupiter.

Dim, blue Neptune is following Jupiter across the sky. It rises at about 12:30 am local time, and sits about 2 fist diameters to the left (celestial east) of Jupiter – near the border between Aquarius and Pisces (the Fishes). Magnitude 5.8 Uranus is bright enough to see in binoculars and backyard telescopes, even near cities. This week it will rise below the bright stars in Aries (the Ram) at about 2 am local time – but that time will move earlier by about half an hour per week.

So – you can see Venus and Mars after sunset, Jupiter and Saturn after midnight, then Neptune and Uranus during the wee hours, and Mercury before sunrise!

Exploring Hercules

The moon out of the evening sky worldwide this week and next will produce excellent conditions for viewing the sky’s best sights. Shortly after it becomes dark on the next clear evening, head outside point your finger directly overhead. That’s the zenith. While objects occupy that position, they will always appear at their best because you are looking through the least amount of intervening air. During late evening in late-June every year, the constellations of Boötes (the Herdsman), Corona Borealis (the Northern Crown), and Hercules sit just below the zenith, high in the southern sky. Let’s focus on Hercules, which contains one of the summer season’s best objects!

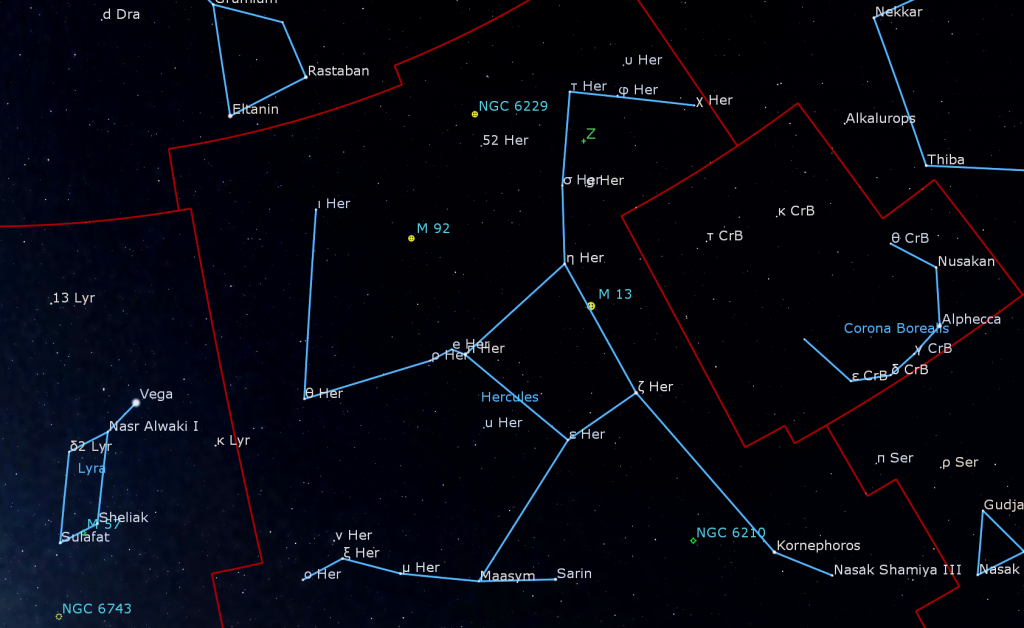

Hercules isn’t composed of bright stars, but you can still find it very easily, even from mildly light-polluted skies. Face southeast and look for a very bright, white star sitting about halfway up the sky. That’s Vega, the extremely bright star in Lyra. Higher than Vega, in the southern sky, is another prominent star, orange-tinted Arcturus. Between these two stellar signposts is the realm of mighty Hercules.

Hercules’ body is defined by a very distinctive keystone-shaped quartet of modestly bright stars. The keystone is about 6° across (a palm’s width), with its wide end to the north (towards your left) and its narrow end pointed southwards (towards the lower right). The hero of mythology is upside down for Northern Hemisphere observers. His sharply bent legs extend upwards to the left, and his two arms are outstretched downward. The star that marks his eastern hand, named Maasym, or Lambda (λ) Herculis, is below the keystone. It combines with four other stars to form a loose chain of five stars running left-right, each separated by a couple of finger widths. In classical drawings Hercules is grasping the three-headed dog Cerberus, which he was tasked with capturing as one of his twelve labours.

Hercules is the fifth largest constellation by area, and was one of the original 48 constellations tabulated in the Almagest, an early astronomy book produced in ancient Greece by Ptolemy. The early Greeks depicted Hercules, with his legs bent – as “The Kneeler” praying to his father Zeus to aid him in an upcoming battle. Beyond his feet, to our upper left, are the stars of Draco (the Dragon), ready to be crushed under his feet. To the upper right (or celestial west) of Hercules is the little circlet of stars that form the distinctive constellation of Corona Borealis (the Northern Crown).

Hercules’ location 30 degrees north of the celestial equator has allowed its stars to be seen everywhere on Earth except the southern tip of South America and Antarctica. Other cultures have formed patterns with the same stars. The indigenous Lokono or Arawak people of northern coastal South America call these stars Katarokoya (the Spirit of the Green Sea Turtle). The Ojibwe of North America used some of Hercules’ stars to form Noondeshin Bemaadizid (the Exhausted Bather) next to Madoodiswan (the Sweat Lodge), from the stars of Corona Borealis.

Let’s tour Hercules. Starting in the keystone, the right-most and brightest star is designated Zeta Herculis (or ζ Her for short). This is a binary star system situated about 35 light-years away from us, where the pair of stars orbit around one another. Both stars are yellow sun-like stars, although the brighter star is more massive and luminous. Moving clockwise and downwards, we arrive at the dimmer white star Epsilon (ε) Herculis. Next, at lower left, is Pi (π) Herculis. It’s a giant, orange-tinted, cool star situated about ten times farther away than Zeta. At the upper left corner of the keystone sits Eta (η) Herculis. It is a yellowish, sun-like star, about ten times the diameter of the sun, but a bit cooler than our sun.

Hercules contains quite a few double and binary stars within reach of a backyard telescope. One of the nicest ones is modest Rasalgethi, or Ras Algethi “Head of the Kneeler”, which sits about 1.6 fist diameters to the lower right (or 16° to the celestial southwest) of Epsilon Herculis. A medium-bright star named Rasalhague sits a slim palm’s width below Rasalgethi. In a small telescope, Rasalgethi easily splits into a lovely pair of orange and greenish stars. The slightly brighter one is a red giant class star that varies in brightness randomly over months to years. The partner is a yellow sun-like star that is itself a binary star too tightly spaced to resolve. The stars are about 360 light-years away and are orbiting one another with a period of 3,600 years. This double star, like many others, was given a single name centuries before telescopes revealed that there was more than one star there.

The brightest star in Hercules, Kornephoros “Club-bearer”, sits a fist’s diameter to the lower right of the keystone, where Hercules’ elbow would be. Only about two finger widths to the lower right (or 3° to the southwest) of Kornephoros is the double star Gamma (γ) Herculis. This is another pair that easily splits into two yellow stars in a modest telescope. But this double is a line-of-sight double star. The fainter star is actually much closer to us! Marsic or Marfik, which means “the Elbow” even though it’s at the end of his arm, is another “line of sight” double star that’s easy in a small telescope. Look for it about four finger widths to the right of Gamma.

Hercules contains one of my favorite objects, a globular cluster known as the Great Hercules Cluster or Messier 13 (or M13). This object is a tightly packed ball of at least 300,000 old stars. At magnitude 5.9, it is visible with unaided eyes under dark skies as a faint smudge, but reveals much more under magnification! It is located along the western (upper) edge of the keystone, about one-third of the way from the wide end. Your binoculars should pick it up. Midway between Hercules’ knees there is another, smaller globular cluster called Messier 92. This one is also readily visible in binoculars. A third, fainter globular cluster designated NGC 6229 sits 6.5°, or a palm’s diameter, to the lower right of M92.

Globular clusters are one of the most interesting classes of objects for stargazers. These spherical concentrations of old, densely packed stars orbit in the region just outside our Milky Way galaxy, and we’ve observed many of them around other galaxies, such as the Andromeda Galaxy. Viewed in a telescope under dark skies, they will look like a pile of salt poured onto black velvet – with a dense white center surrounded by a sprinkling of outlying stars. Each cluster looks different, varying in the scattering of stars. Photographs reveal that these objects contain a mixture of reddish, blue, and yellow stars in different proportions.

The Great Hercules Globular Cluster was first observed by British astronomer Edmund Halley in 1714 and later included as number thirteen in Charles Messier’s famous list of “not-a-comet” objects. At 21,500 light-years away, it is a relatively close member of that class of objects. It shines with a relatively bright magnitude of 5.8, and it actually covers an area of sky spanning 20 arc-minutes (or two thirds of the moon’s diameter)!

More than 150 of these clusters have been mapped around our galaxy. They are so densely packed that the stars in their interiors are extremely close together, stirring the imagination of those contemplating extraterrestrial intelligent life. Advanced civilizations on planets around stars embedded deep inside a globular cluster would be able to exchange radio messages on timescales of weeks or months – and travel between adjacent solar systems would not require the decades or centuries we would need to visit our nearest neighbours. In fact, M13 was also one of the first targets for potential contact with other civilizations, when a radio message was beamed there from the Arecibo Radio Observatory in 1974.

The stars of Hercules are host to at least fifteen known exoplanets, including one named TrES-4. At 1.7 times the mass of Jupiter, it’s one of the most massive exoplanets yet discovered. However, its calculated density is extremely low, about the same as cork! This is one of the hot-Jupiter class of exoplanets, with a surface temperature in excess of 2,000 C.

Let me know how your exploration of Hercules goes.

Public Astro-Themed Events

Every Monday evening, York University’s Allan I. Carswell Observatory runs an online star party – broadcasting views from four telescopes/cameras, answering viewer questions, and taking requests! Details are here. Their in-person Wednesday night viewing has been converted to online via the observatory YouTube channel. This week, they’ll be hosting a celebration in honour of Professor Paul Delaney, who is stepping down as a director of the observatory. Details are here.

Don’t forget to take advantage of the astronomy-themed YouTube videos posted by RASC Toronto Centre and RASC Canada.

On Monday, June 28 at 5 pm EDT, University of Toronto’s Astronomy & Space Exploration Society (ASX) will present a free online Star Talk by Dr. Daniel Gilman, Postdoctoral Fellow at the University of Toronto’s David A. Dunlap Department of Astronomy & Astrophysics. His talk is entitled Revealing the Nature of Dark Matter with Strong Gravitational Lensing. Details and the Zoom registration link are here.

My free, family-friendly Insider’s Guide to the Galaxy webcasts with Jenna Hinds of RASC National will return in July with a Summer Planets Spectacular! You can find more details, and the schedule of future sessions, here and here.

Keep looking up, and enjoy the sky when you do. I love questions and requests. Send me some!