Appreciating Pegasus While the Moon Abandons Evening, the Bull Bellows Meteors, and Mars Makes an Impression!

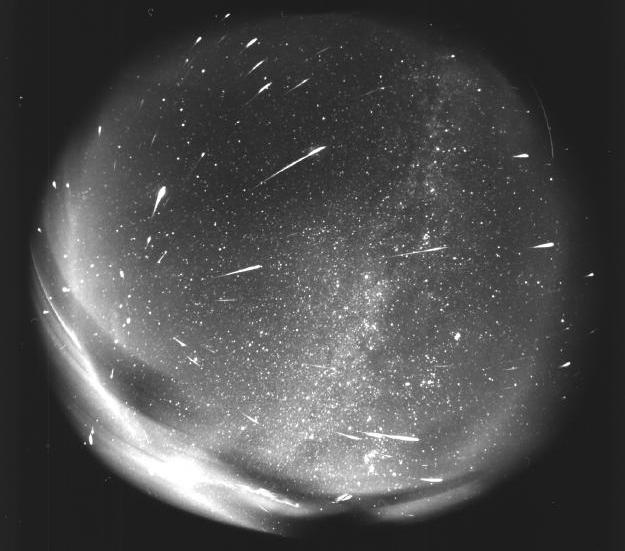

My friend Alan Dyer of Calgary, Alberta captured this wonderful wide-field image of the fully eclipsed moon on Tuesday morning, November 8, 2022. The brilliant white star Sirius (lower left), bright red Mars (top centre), and the blood red moon (far right) surround the winter stars of Orion and Taurus. Enjoy more of Alan’s work at https://www.amazingsky.com/

Hello, November Stargazers!

Here are your Astronomy Skylights for the week of November 13th, 2022 by Chris Vaughan. Feel free to pass this along to your friends and send me your comments, questions, and suggested topics. You can also follow me on Twitter as @astrogeoguy! Unless otherwise noted, all times are expressed in Eastern Time. To subscribe to these emails please click this MailChimp link.

If you’d like me to bring my Digital Starlab portable inflatable planetarium to your school or other daytime or evening event, or deliver a session online, contact me through AstroGeo.ca, and we’ll tour the Universe, or the Earth’s interior, together! My terrific book with John A. Read entitled 110 Things to See With a Telescope is a guide to viewing the deep sky objects in the Messier List – for both beginners and seasoned astronomers. DM me to order a signed copy!

The moon will wane and move into morning this week, where it will interfere with the Leonids meteor shower. Mercury and Venus are the only planets missing from evening skies. We dive deeply into Pegasus and de-mystify the celestial coordinate system. Read on for your Skylights!

More Meteors

Meteor season continues! Meteors from the Northern Taurids meteor shower, which appear worldwide from October 20 to December 10 annually, reached its maximum on Saturday afternoon, November 12 in the Americas. You can continue to look for those colorful fireballs streaking away from Taurus while they taper off during this week.

The Leonids Meteor Shower, which is derived from bits of material dropped when periodic Comet 55P/Tempel-Tuttle traverses the inner solar system every 33 years, runs from November 5 to December 2, annually. The peak of the shower, when up to 15 meteors per hour are typical, will occur on Thursday evening in the Americas. At that time Earth will be traveling through the densest part of the comet’s debris field. The particles hit the atmosphere over our heads at such a high speed that they ionize the air through friction, producing the streaks of light you see as “shooting stars”. Many Leonids have persistent trains and strong colour.

This shower is a worldwide event. The meteors can appear anywhere in a dark sky, but true Leonids will be travelling in a direction away from a location called the radiant that is positioned among the stars that form the head of Leo (the Lion). (The radiant’s location gives each shower its name.) Don’t focus your attention on the radiant – the meteors near it will have very short streaks because they are traveling directly towards you.

While you should see some Leonids after dusk on Thursday evening – many with persistent trains – more meteors will be apparent on Friday in the hours before dawn, when the radiant will be highest in the southeastern sky. Unfortunately, the bright waning crescent moon, which will rise at around 1 am local time on Friday morning, will reduce the quantity of fainter meteors we see. If you do venture out, find a safe, dark location with lots of open sky, get comfortable, and just look up.

To preserve your dark adaptation, try to keep your phone tucked away. If you must look at it, turn the screen brightness to minimum, and/or enabled the red screen mode available on some models. Don’t try to see meteors through binoculars or a telescope – those instruments have a field of view that is too narrow. But you can take long exposure photos of the sky and catch the meteors’ streaks. If the peak night is cloudy, don’t despair – the surrounding dates will still deliver some meteors. Happy viewing!

The Moon

This week, the moon will be waning in illuminated phase and rising later and later, delivering darker evening skies worldwide as the week wears on. Tonight (Sunday), when the bright gibbous (71%-illuminated) moon rises before 9 pm in your local time zone, it will be aligned with Gemini’s brightest stars Pollux and Castor. At first the moon will appear several finger widths below (or 3.5 degrees to the celestial southeast of) Pollux – close enough to share the view in binoculars. Somewhat less-bright Castor will shine above them. By 6 am on Monday, the eastward orbital motion of the moon will carry it a little farther from Pollux and bend their alignment. Meanwhile, the diurnal rotation of the sky will pivot their line to horizontal.

When the still-gibbous moon rises in the east during late evening on Monday, it will be positioned several finger widths to the upper left (or about 3 degrees to the celestial north) of the large open star cluster known as the Beehive (and Messier 44) in Cancer (the Crab). The moon and the cluster will fit within the field of view of binoculars, although the bright moonlight will obscure the cluster’s dimmer stars, which are loosely scattered over nearly triple the moon’s diameter. To better see the “bees”, hide the moon just beyond the upper left edge of your binoculars’ field of view. The cluster also looks spectacular in any size of telescope – but use your weakest, lower power, eyepiece.

From Tuesday to night, the late-rising moon will sneak through the large constellation of Leo (the Lion). Some observers prefer to flip the picture around and see the stars of Leo as a mouse. Watch out moon – it wants your cheese! You can see the moon with Leo fairly high in the southern sky before dawn from Wednesday to Friday morning. The moon will complete three quarters of its orbit around Earth, measured from the previous new moon, on Wednesday, November 16 at 8:27 am EST, 5:27 am PST, or 13:27 Greenwich Mean Time. At the third (or last) quarter phase the moon appears half-illuminated, on its western, sunward side. It will rise around midnight local time, and then remain visible until it sets in the western daytime sky in early afternoon. Third quarter moons are positioned ahead of the Earth in our trip around the Sun. About 3½ hours later, Earth will occupy that same location in space. The week of dark, moonless evening skies that follow this phase are the best ones for observing fainter deep sky targets.

To end this week, the gorgeous, elderly crescent moon will shine in the southeastern pre-dawn sky among the stars of Virgo (the Maiden).

The Planets

Mercury and Venus have both entered the western sky now – but they are still far too close to the sun to be observable from mid-northern latitudes. Lucky observers in the tropics and farther south should be able to spot Venus’ very bright magnitude -3.93 dot low above the west-southwestern horizon starting about 15 minutes after the sun has completely set.

By 7 pm in your local time zone, the rest of the planets – and two bright asteroids – will be above the horizon. Another asteroid will rise towards midnight. Let me break down your evening of planet-watching!

With the sun setting so early now at mid-northern latitudes, the pale yellow dot of Saturn will appear in the south as the sky darkens. Much brighter Jupiter to its left will draw your attention, but let’s focus on the magnitude 0.7 ringed planet, as it will set first – at about 11 pm local time. Planets appear most clearly in backyard telescopes when they are highest in the sky. Saturn will culminate (i.e., reach its highest point) just as the sky is fully darkening after 6 pm – so that’s your best time to view it.

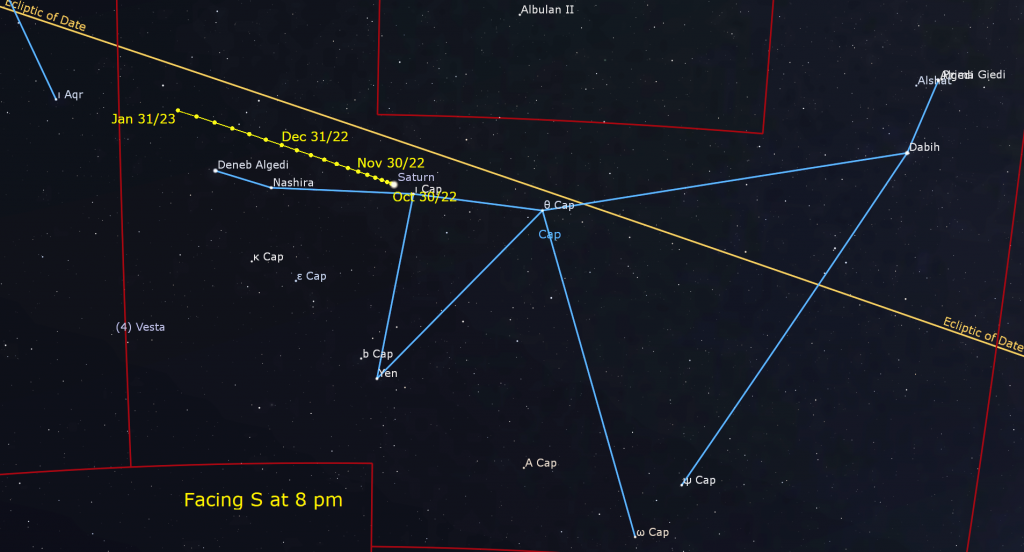

Saturn will be shining above the relatively faint stars of Capricornus (the Sea-Goat). In the coming months, you’ll be able to notice that Saturn is shifting to the left above the left-right pair of stars that form the sea-goat’s tail. They are Deneb Algedi on the left, or celestial east, and Nashira on the right, or celestial west. Binoculars will work particularly well for this kind of observation.

On a night with steady air, good binoculars in the range 10×42, 10×50, or larger should present Saturn and its rings as a tiny oval. On those nights, even a small telescope can show Saturn’s subtly banded globe encircled by its glorious rings, which are sufficiently edge-on to Earth to allow Saturn’s southern polar region to extend well below the ring plane. (Your telescope might flip the planet.) See if you can make out the Cassini Division, a narrow, dark gap that separates Saturn’s main inner ring (named B) from its bright outer ring (named A).

Saturn’s position far to the west of the anti-solar point has caused the planet’s globe to cast a widening wedge of dark shadow onto the rings where they emerge from behind the eastern limb of the planet. That wedge of shadow reached its maximum size last week, when Saturn was 90° away from the sun in the sky. From now on it will shrink. Where you see that shadow will depend upon how your telescope flips and/or mirrors the view. In a refractor or SCT telescope, it will show toward the upper right. In a Newtonian reflector, it will be toward lower right. An equatorial mount will rotate the scene, too.

A small telescope can also pick up several of Saturn’s moons – especially its largest, brightest moon, Titan! From here on Earth, Saturn’s axial tilt of 26.7° lets us see the top of its ring plane, and allows its brighter moons to array themselves all around the planet. If Jupiter had Saturn’s bright, icy ring, we would barely see it as a thin line through Jupiter’s centre because Jupiter’s axis is only tilted by 3°.

Titan never wanders more than five times the width of Saturn’s rings from the planet. The much fainter moon named Iapetus can stray up to twelve times the rings’ width during its 80-day orbit of Saturn. The next brightest moons Rhea, Dione, Tethys, Enceladus, and Mimas all stay within one ring-width of Saturn. During evening this week, Titan will migrate counter-clockwise around Saturn, moving from the left (or celestial east) of Saturn tonight (Sunday) to the right (or celestial west) of Saturn next Sunday. (Remember that your telescope might flip that view around.) How many of the moons can you see in your telescope?

In the darkening twilight after sunset, the extremely bright, magnitude -2.7 planet Jupiter will become visible in the southeast. Its gleam will definitely catch your eye as dusk arrives. Jupiter will culminate due south shortly around 9 pm local time. Then it will set in the west before 3 am local time.

Your binoculars will show Jupiter as a small disk flanked by its string of four Galilean moons named Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto. They complete orbits of the planet every 1.7, 3.6, 7.2, and 16.7 days, respectively. If you see fewer than four moons, then one or more of them is crossing in front of or behind Jupiter, or lurking in Jupiter’s dark shadow – or two of the moons are very close together or occulting one another. Their arrangement varies each night.

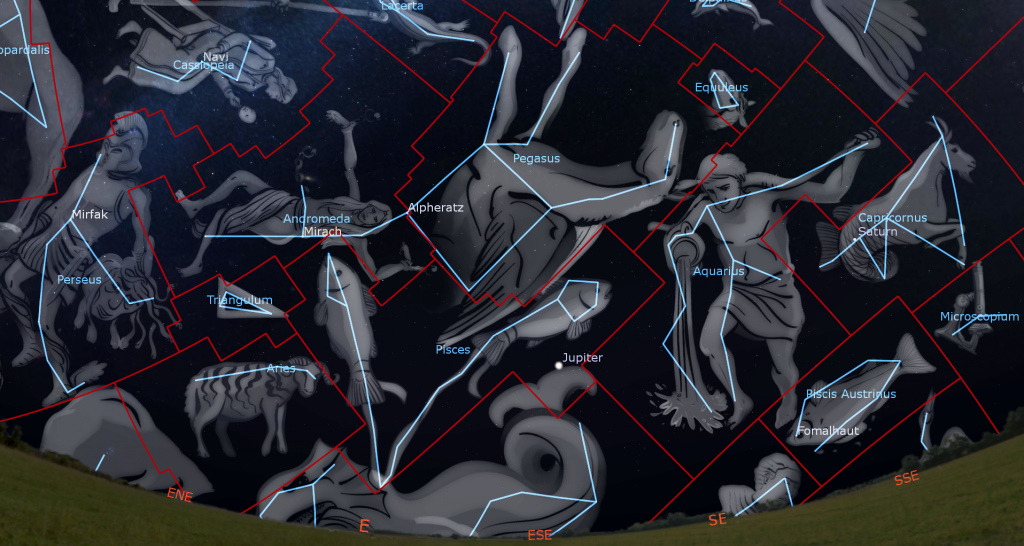

Use your binoculars to spy a pentagon-shaped ring of low-brightness stars shining about a fist’s diameter above Jupiter. They make up the western head of Pisces (the Fishes). Above those stars, the Great Square of Pegasus (the Flying Horse) will be visible, even with your unaided eyes. It’s located about 2.5 fist diameters above Jupiter. (More about Pegasus later.)

Any decent telescope can show you Jupiter’s dark belts and light bands, which are aligned parallel to its equator. With a better grade of optics, Jupiter’s Great Red Spot, a cyclonic storm that has raged for hundreds of years, is visible for several hours when it crosses the planet. Because Jupiter rotates once every 10 Earth-hours, the GRS appears every 2nd or 3rd night. You can see it with a good quality backyard telescope. For observers in the Americas, that GRS will cross Jupiter’s disk in early evening on Sunday, Wednesday, and Friday, late on Tuesday, Thursday, and Sunday evening, and after midnight on Tuesday and next Sunday. If you have any coloured filters or nebula filters for your telescope, try enhancing the GRS with them.

The round, black shadows of Jupiter’s Galilean moons are visible through a good backyard telescope when they cross the planet’s disk. For observers in the America’s, Io’s shadow will cross Jupiter’s equator on Tuesday night between 11:23 pm and 1:30 am EST. On Wednesday evening, the small shadow of Europa will cross the southern hemisphere of the planet from 10:45 pm to 1:05 am EST. Don’t forget to adjust these quoted times into your own time zone.

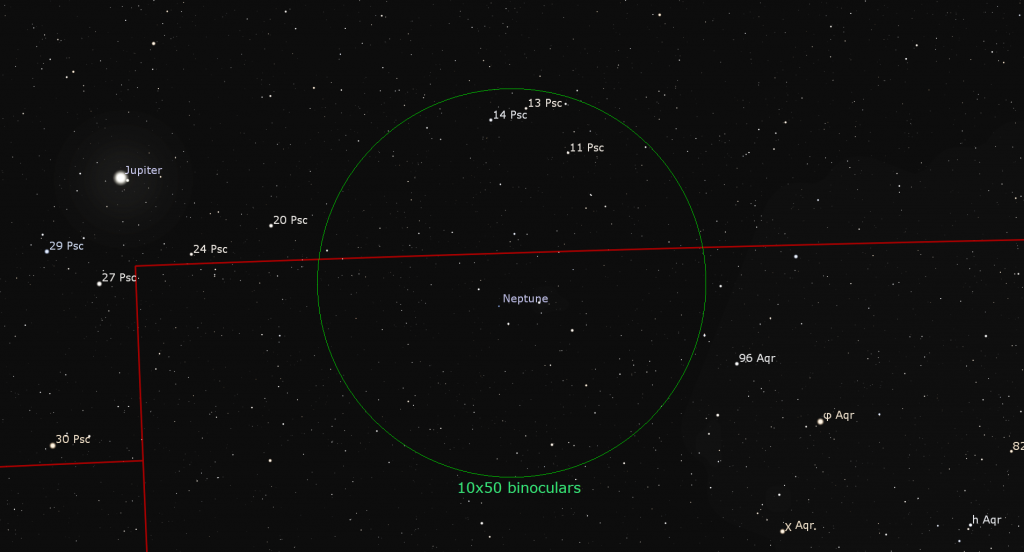

Magnitude 7.8 Neptune is located a palm’s width to the right (or 6° to the celestial west-southwest) of Jupiter, which will slide a wee bit closer to the distant planet every night. Neptune’s apparent disk size is 2.4 arc-seconds (20 times smaller than Jupiter’s). Try to view Neptune while it is highest, around 8:15 pm. Neptune is binoculars-close to several groups of medium-bright stars. The large asteroids designated (4) Vesta and (3) Juno are currently between Jupiter and Saturn, too.

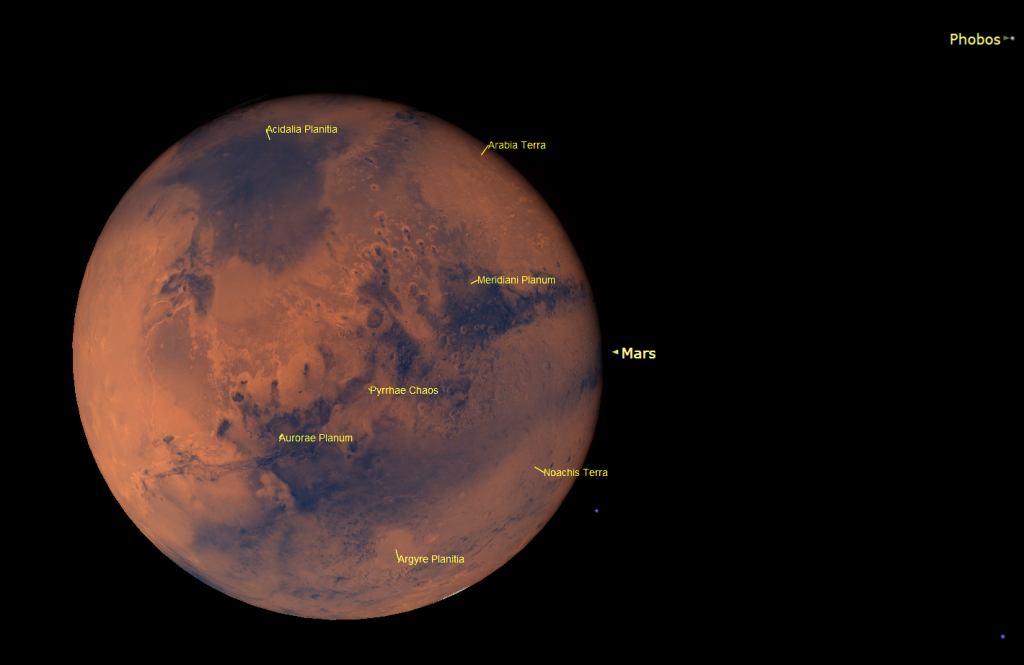

This week, the red planet Mars will be rising over the northeastern horizon by 6:30 pm in your local time zone – completing our full set of planets. (I’ll talk about Uranus below.) Mars’ rising time will shift earlier by 5 minutes each night – so that next Sunday it will be up by 6 pm!

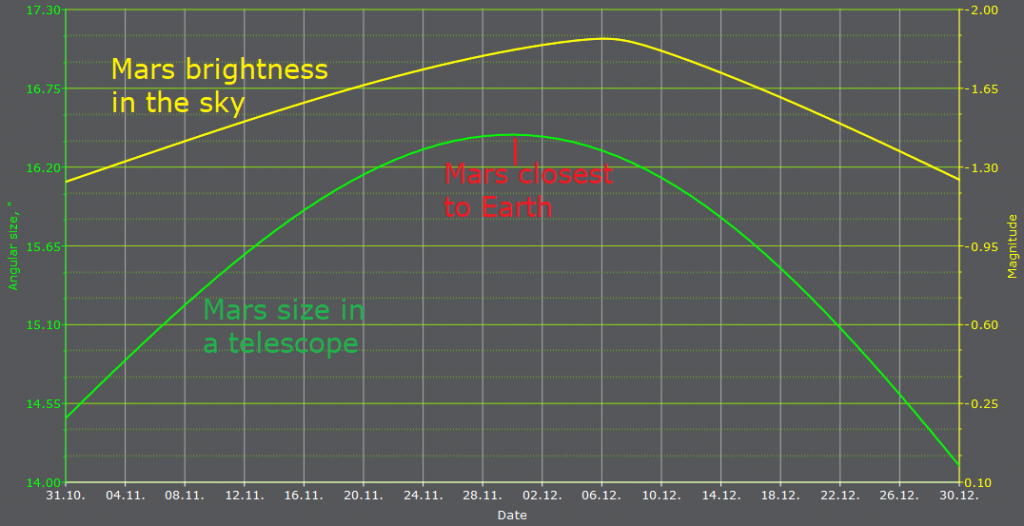

Over the next 2.5 weeks, Mars will grow in apparent size (in your telescope’s eyepiece) and increase its visual brightness in the sky (currently at magnitude -1.52) – all because Earth is passing the red planet on the inside track. The two planets’ minimum separation, which happens every 25.5 months, will occur around midnight Eastern Time on November 30. This week, we’re 85 million km, or 4.75 light-minutes away, and closing.

Mars is a terrific object to view in a backyard telescope when it gets this close. This week, Mars will climb highest, and sit due south, around 2 am local time – but views during late evening will be nearly as good. In a telescope this week, Mars will show a waxing, 97%-illuminated disk. If the air is steady you might see some dark markings wrapping around the planet and the white patch of its northern polar cap. Mars takes about 20 minutes longer than Earth to rotate once fully on its axis. So viewing the planet at the same local time on subsequent nights will show roughly the same view of it with surface markings turned by about 5°. If you have coloured filters for your telescope, see if the blue, orange, or red one improves the view.

Due to Earth’s faster motion, Mars is experiencing a westerly retrograde loop that will last through its December opposition and into mid-January. This week, Mars will be positioned between the two horn tips of the bull, composed of the medium-bright stars Zeta Tauri (the lower star) and Elnath or Beta Tauri (the higher star). Over the next month, you can watch Mars swing between those stars and then race west towards the bright orange star Aldebaran and the Pleiades star cluster.

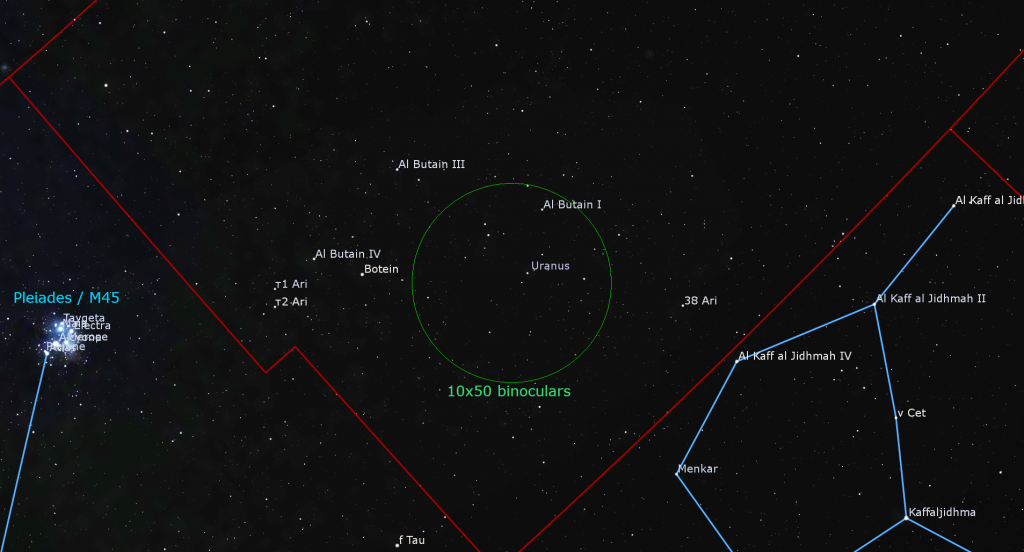

I skipped over Uranus until now because the distant blue-green planet is located about midway between Mars and Jupiter, and about 1.3 fist widths to the upper right (or 13° to the celestial west-southwest) of the Pleiades star cluster. Closer guideposts to Uranus are several medium-bright stars, including Botein (or Delta Arietis), Al Butain II (or Rho Arietis), and Sigma Arietis, which will appear several finger widths from the planet. Those stars mark the feet of the Aries (the Ram). I had no trouble seeing Uranus and those stars through my 10×42 binoculars during the lunar eclipse last week.

Magnitude 5.7 Uranus will be high enough for telescope-viewing, in the lower part of the eastern sky, by 8 pm local time this week. It will be highest, in the southern sky, approaching midnight. Uranus reached opposition last Tuesday night / Wednesday morning, so it is still nearly closest to Earth and shining at peak brightness for this year.

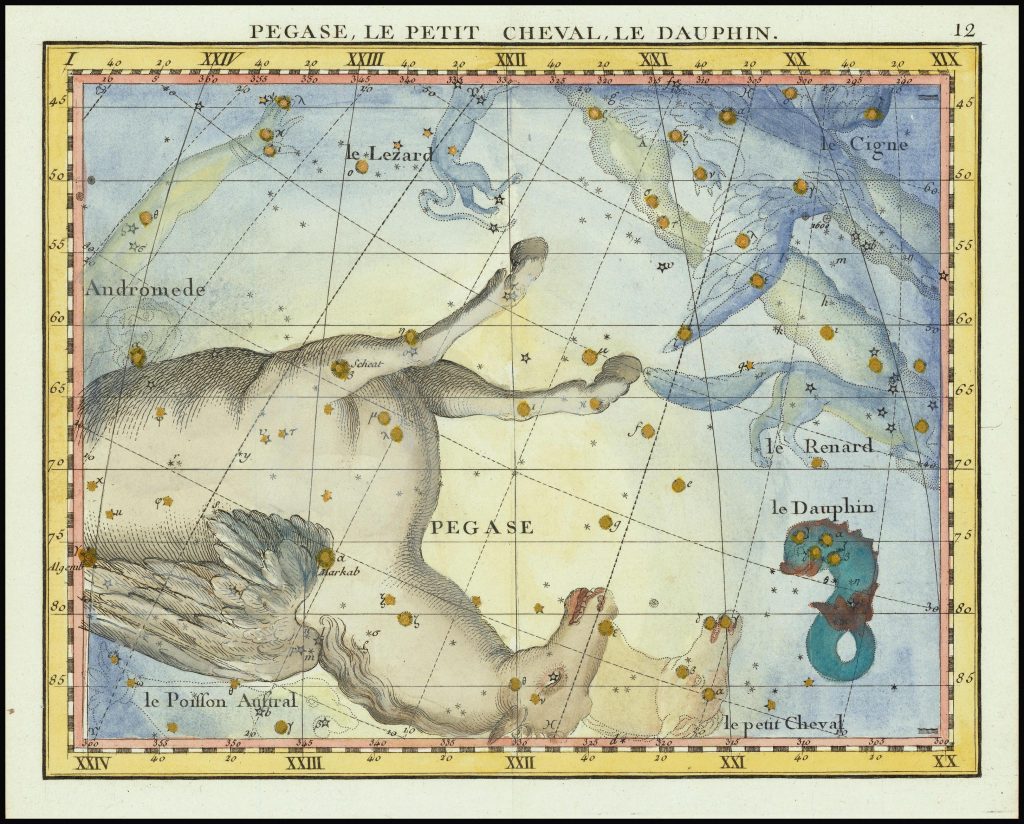

Pegasus Flies on High

Fall and winter evening skies feature a group of easy-to-see constellations that are characters in a grand story from Greek mythology – the tale of Princess Andromeda and her rescue by the hero Perseus. I’ll relate that tale in a future Skylights. This week, we’ll look at Pegasus – the westernmost constellation in the myth. But, first, let’s flesh out that story a little more…

Before hunting the Gorgon Medusa, Perseus was given some magical gifts to aid him in his quest, including winged silver sandals called the Shoes of Swiftness. Immediately after slaying the snake-haired Medusa by cutting off her head, he flew into the air to avoid Medusa’s angry sisters. While hovering there, some of the gorgon’s blood dripped onto the seashore below. Poseidon, god of the Sea, mixed the blood with some sea foam, and the magical flying horse Pegasus, whose name is related to the Greek word for wellspring “pegai”, sprang from the sea.

Pegasus has traditionally been associated with beauty, wisdom, and poetry. In some stories, the majestic, wild, white stallion was tamed by the warrior Bellerophon, the most successful hero of ancient Greece (until Hercules came along later). After many heroic deeds astride Pegasus, Bellerophon felt that the he was worthy of living in Olympus with the gods, and attempted to ride Pegasus there. But the Olympians denied him – sending a bee to sting Pegasus, who bucked and tossed Bellerophon from his saddle. The hero died from the fall to Earth, but he has an interesting role among the stars – as we’ll cover below. Zeus then added Pegasus to his stables, using him to transport thunderbolts. As a reward for his service, at the end of the horse’s days, he was granted a place among the stars.

The constellation Pegasus (the Winged Horse) appears in the eastern evening sky in September, becomes well placed for evening astronomy, high in the southern sky from October to December, and then gradually sinks into the western twilight by February. It is one of the largest and oldest of the 88 modern constellations – 7th by area. Since it occupies a place in the sky just north of the celestial equator, it is visible from almost everywhere on Earth. Only Antarctica never sees it rise.

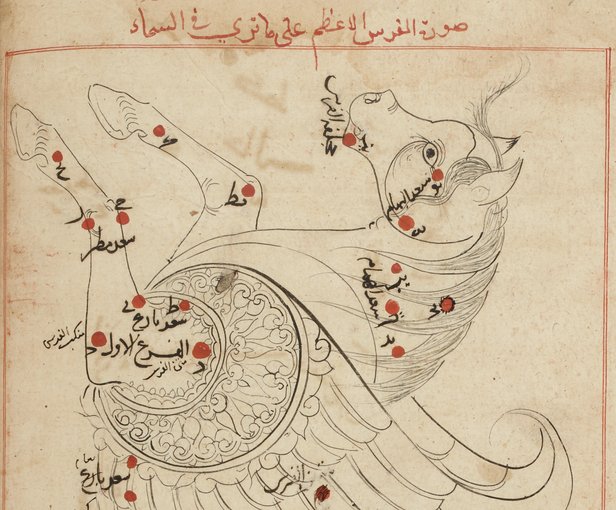

Pegasus has traditionally been depicted upside-down, with a square of stars representing his wings, and chains of stars extending westward forming his head and neck, and two front legs. The stars where the rest of him should be are occupied by the water constellation of Pisces (the Fishes) – with Aquarius (the Water-Bearer) situated to the right (west), below Pegasus’ head. According to some scholars the ancient Phoenicians envisioned Pegasus as a bridled horse affixed to the prow of their ships – explaining his missing hindquarters and the nautical theme of the surrounding constellations.

To the right (or celestial west) of Pegasus’ head is a tiny and dim constellation composed of four stars called Equuleus (the Little Horse). Some cultures referred to Pegasus as the Second Horse, because Equuleus rose first and led the way across the sky. Beyond Pegasus’ forelegs sits the prominent constellation of Cygnus (the Swan), with its bright Summer Triangle star Deneb. Between Cygnus and Equuleus swims tiny Delphinus (the Dolphin). Lacerta (the Lizard) scampers to the north of Pegasus – “under” the horse’s front feet. Finally, adjoining Pegasus on the left-hand (eastern) side, and sharing one major star with him, is Andromeda (the Princess).

Pegasus contains one of the most obvious asterisms in the sky – a giant square made from four, equally bright stars called the Great Square of Pegasus. Its shape will probably remind you of a baseball diamond when you see it, because it’s usually tilted with one corner downwards. An asterism is a shape or pattern in the sky made up of prominent stars – either stars from a single constellation, or a combination of stars from adjacent constellations. The Big Dipper is an asterism that uses only part of its large constellation Ursa Major.

For the Lakota people, the square represented the great shell of Keya, the Turtle. The Anishinaabe of the Great Lakes region view the square as the torso of Mooz, the Moose. Using unaided eyes only, from the suburbs, the Great Square appears empty. Look carefully for two dim stars offset slightly upper right from the centre of the square – they represent the moose’s heart. Hunting of the moose is only allowed while Mooz is visible in the night sky. That way, the calves can be safely born in spring.

In Chinese astronomy, the stars of Pegasus make up the Black Tortoise of the North, one of the four legendary Benevolent Animals in the stars. The pre-Islamic nomadic Arabs saw the square as “Al Dalw”, the “Water bucket” of Aquarius. To draw water from a deep well, desert travelers would take a water skin and prop the mouth open using crossed sticks lashed to each corner, forming a square opening. When empty, the water skin could be stowed flat or rolled up on the flanks of a camel. The square may also have been, “Al ‘Arkuwah”, the well in which such a bucket was used.

In Arabic astrology, the westerly stars of the Great Square, Markab and Scheat, were together called Al Fargh al Mukdim, the fore-spout (of the bucket). The eastern two stars, Algenib and Alpheratz, were called Al Fargh al Thani, the rear spout. Those two fainter stars inside the square, today designated Tau Pegasi and Upsilon Pegasi, were Salm “a Leather Bucket” and Al Karab “the Bucket-rope”. They may also represent the intersection of the lashed-together sticks holding the bucket open!

Let’s tour Pegasus’s stars. After it gets dark, face the southeastern sky. The square’s edges are about 16° long (or 1.6 fist widths when held at arm’s length), and about 20° from corner to corner. In mid-November at 7 pm local time, the square’s centre is halfway between the horizon and the zenith. It’s highest in the southern sky at 8:30 pm local time. It will set in the west during the wee hours.

The star at the bottom (southeastern) corner of the diamond is Algenib, derived from the Arabic الجنب Al-janb or Al-jānib, “the flank”. It’s a very hot blue-white star of moderate brightness that is located about 350 light-years away from us. It actually emits 4,000 times more light than our sun! Traveling the square counter-clockwise, the white star at the right-hand corner is Markab “the Saddle”. This star appears slightly brighter than Algenib. It emits less light than Algenib, but it looks just as bright because it is closer to us – only 140 light-years away. In some old star atlases, Markab was labelled Matn al Faras, “the horse’s withers”, or “shoulder”.

From Markab, look farther to the right (west) for the dimmer stars that trace the horse’s neck and head. A palm’s width from Markab is the blue star Homam from the Arabic Sa’d al Humām “Man of High Spirit”. Another fist’s width further is Biham, named from S’ad al Biham “lucky stars of the young beasts”. Both stars shine with the same brightness. A somewhat fainter star named Al Fum al Faras “the mouth of the horse” is located a thumb’s width to the right of Biham.

From Biham look a palm’s width higher to the right for bright star Enif, named from الأنف Al’anf “the Nose”. Enif is a low-temperature, orange supergiant star located 670 light-years away from us. It is nearing the last stages of its life cycle. You should be able to perceive that its warm colour. Enif is huge! Were it to replace our Sun, it would span 40° of Earth’s sky, eighty times wider than the sun or moon! Enif is just at the lower mass limit for becoming a supernova. Use binoculars to scan the sky about four fingers widths to the upper right (celestial west) of Enif. You’ll find a small, dim, but pretty, fuzzy patch of stars designated Messier 15. That globular star cluster of 100,000 stars is 33,000 light-years away from us. In a telescope, it will resemble salt sprinkled on velvet.

Resuming our trip around the diamond, the fairly bright, magnitude 2.4 star at the top (northwestern) corner is Scheat “the Foreleg”, the second brightest star in the constellation. That name may arise from the expression Al Sā’id “the upper part of the arm”. Scheat is a cool, red giant star located 200 light-years away from us. Pegasus’ two front legs start at Scheat and extend upwards to the right. Five degrees to the right of Scheat is the dim yellow star Matar, from سعد المطر Al Saʽd al Maṭar “Lucky Star of Rain”. The leg terminates a palm’s width farther in the same direction – at a double star designated Pi Pegasi or π Peg. Using binoculars you should be able to see that Pi consists of two close-together, yellow-white stars.

The second foreleg takes a jog to the lower right (celestial southwest) before bending back up parallel to the first one. A well-spaced pair of yellowish stars named Sadalbari “auspicious star of the splendid one” and Sadalnazi “auspicious star of the camel”, or Lambda Pegasi or λ Peg, marks the knee. That leg continues to the faint white star Iota Peg, parked a fist’s width to the upper right, and ends at a dim white star farther along that line named Kappa Peg.

There’s a dim yellow star sitting a thumb’s width just outside of the baseball diamond, midway between the top and right corners. This is the sunlike star designated 51 Pegasi. It hosts the first exoplanet ever discovered, in 1995 – a Jupiter-sized planet that orbits that star every 4.23 days at a distance much closer than Mercury does in our solar system. Planets like this are called hot Jupiters. Initially, the planet was nick-named Bellerophon, one of the original riders of Pegasus in Greek mythology. Now it is officially named Dimidium, the Latin word for “half” – since the planet has half the mass of Jupiter. Take a look at the star in your binoculars and let your imagination soar, like Bellerophon!

The final star of the square, at the upper left (northeastern) corner, is called Alpheratz, a name derived from the Arabic phrase سرة الفرس Surrat al-faras “navel of the mare/horse”. It’s another hot, blue-white supergiant star, but it is located only 97 light-years away from us. The spectrum of this star’s light indicates that it is highly enriched in the metal Mercury. In actuality, Alpheratz does not belong to Pegasus. It’s the brightest star in Andromeda, and marks the princess’ head – but that’s a tour for another night!

For Skylights readers with larger aperture telescopes or astro-cameras, Pegasus is loaded with galaxies! This is because the constellation is well away from the obscuring gas and dust of our Milky Way, allowing us to peer deeper into the Universe. One of my favorite sights is NGC 7479, also designated Caldwell 44, an S-shaped spiral galaxy that resembles Superman’s sigil. In fact – the galaxy’s nickname is the Superman Galaxy! Another is the Propeller Galaxy.

A few finger widths above (or 3 degrees to the celestial north of) the midway point along the line joining Matar to Eta Peg, you’ll find a particularly busy assortment of galaxies! The Deer Lick Group is composed of the large, magnitude 9.48 spiral galaxy named NGC 7331, plus a number of minor satellite galaxies, the “Fleas”. Although discovered in 1784 by William Herschel, the unusual name was apparently coined by astronomer Tomm Lorenzin, co-author of “1000+ The Amateur Astronomers’ Field Guide to Deep Sky Observing”, who observed it from Deer Lick Gap in the mountains of North Carolina.

Just half a degree below (south) of the Deer Lick you’ll find the tight little Stephan’s Quintet – a gravitationally bound set of five galaxies. Both sets will all appear together in the field of view of a large aperture telescope at low magnification.

Before you call it a night, take a moment to seek out the Andromeda Galaxy. It is climbing the eastern evening sky. An all-night target, this large spiral galaxy, also designated Messier 31, is only 2.5 million light years away from us, and subtends an area of sky measuring 3 by 1 degrees – that’s six full moon diameters by two! Under dark skies, the galaxy can be seen with unaided eyes as a faint smudge located 1.4 fist diameters to the left (or 14 degrees to the northeast) of the square of Pegasus. The three westernmost stars of Cassiopeia (the Queen) – namely Caph, Shedar, and Navi, also conveniently form a triangle that points downwards towards Messier 31. Binoculars will reveal the galaxy better. In a telescope, use low magnification and look for M31’s two smaller companion galaxies, the foreground Messier 32 and more distant Messier 110.

The Celestial Coordinate System

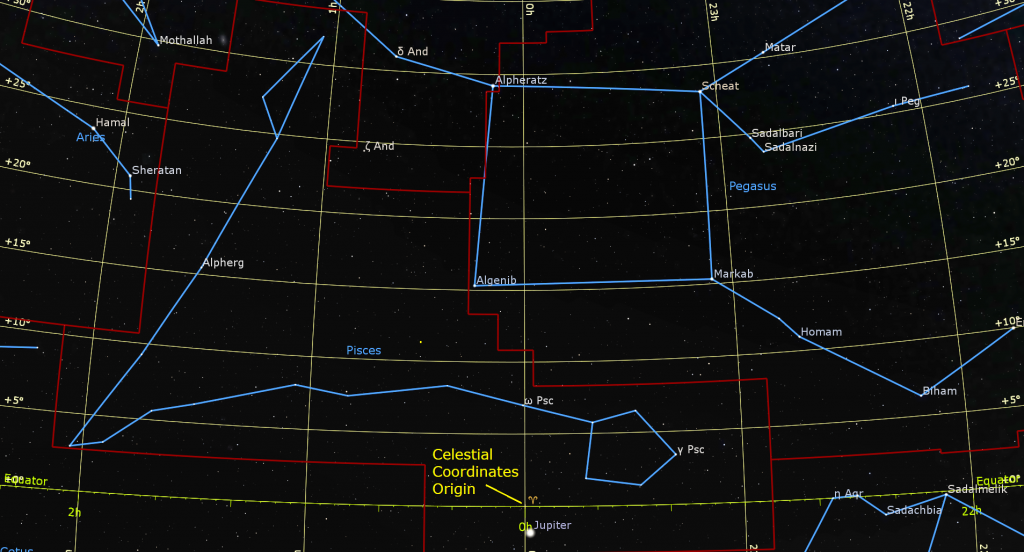

Before we turn away from Pegasus, take a moment to reflect that the left-hand, eastern side of the Great Square is close to, and nearly parallel to, the prime meridian of the celestial sphere. On Earth, the Prime Meridian stretches from the North Pole southward through Greenwich, UK, and then continues to the South Pole. Earth longitude coordinates are measured east and west from that line using degrees. For the sky’s globe, the prime meridian begins at the north celestial pole near Polaris, and extends southward through the constellations of Cepheus (the King), Pegasus, Aquarius (the Water-Bearer), Piscis Austrinus (the Southern Fish), and the lesser-known (for Northerners) constellations of Grus (the Crane) and Tucana (the Toucan) – ending at the south celestial pole in Octans (the Octant). Unfortunately, there is no bright star marking that pole.

To measure east-west in the sky, astronomers use Right Ascension, abbreviated R.A., instead of longitude. In lieu of circumventing the globe from 180 degrees east to 180 degrees west, with each degree subdivided into minutes and seconds, the Right Ascension units are time, employing the length of Earth’s day, from 0 to 24 hours. The sky coordinate for any object along the prime meridian is both 0 hours 0 minutes 0 seconds, or 00h00m00s, and 24h00m00s. Right Ascension values increase moving east in the sky because an easterly object will rise at a later time than a westerly object.

The square’s stars Alpheratz and Algenib are positioned at R.A. 00h09m30s and R.A. 00h14m21s, respectively, about two thumbs’ widths east of the prime meridian. Following that edge north toward Polaris, you’ll pass the bright star Caph in Cassiopeia (the Queen) at R.A. 00h10m19s.

Extending the meridian southward, you’ll cross the Celestial Equator (or declination 0°0m0s) a few finger widths below (or 3.5° to the celestial southeast of) the ring of stars that form the western fish in Pisces. That’s the origin point of the celestial coordinate system. The star that is closest to that spot and visible to your unaided eyes and binoculars is XZ Piscium, a magnitude 5.75, reddish M-class star. It’s only a finger’s width from the 0,0 coordinate. In November, 2022, Jupiter is sitting close to that spot in the sky.

That meridian was selected as prime because the sun passes that point in the sky every year at the Vernal Equinox in March. Over many years the slow precession, or wobble, of the Earth’s axis of rotation shifts the coordinate system. That’s why star charts are assigned an epoch, such as 2000.0. Apps like Stellarium often report the “of date” or current, coordinates.

Public Astro-Themed Events

Every Monday evening, York University’s Allan I. Carswell Observatory runs an online star party – broadcasting views from four telescopes/cameras, answering viewer questions, and taking requests! Details are here. They host in-person viewing on the first clear Wednesday night each month. On Wednesdays they stream views online via the observatory YouTube channel. Details are here.

On Wednesday evening, November 16 at 7:30 pm EDT, the RASC Toronto Centre will live stream their monthly Speakers Night meeting. This month will feature Ismaël Moumen of the Université Laval and the Canada France Hawaii Telescope. His talk is titled “Observation of galaxies in the era of 3D spectroscopy”. Everyone is invited to watch the presentation live on the RASC Toronto Centre YouTube channel. Details are here.

My free, family-friendly Insider’s Guide to the Galaxy webcast with Samantha Jewett of RASC National returns on Tuesday, November 22 at 3:30 pm EST. We’ll focus on the various catalogues we use to list deep sky objects (nebulae, galaxies, and clusters) and we’ll launch our tour through RASC’s Finest NGC objects observing program. You can find more details and the schedule of future sessions here.

Keep looking up, and enjoy the sky when you do. I love questions and requests. Send me some!