Bright Planets Bracket the Night, and Moonless Evenings Offer Stargazing Sights and a Messier Marathon Opportunity

This image by Martin Gembec of the Czech Republic shows the rich starfield of the Alpha-Persei Moving Group stars surrounding Mirfak (above centre), the brightest star in Perseus (the Hero). The photograph spans about 3.5 degrees of the sky, nearly filling the view in binoculars. Mirfak is the very bright star shining about halfway up the northwestern sky on March evenings. (Wikipedia)

Hello, Early March Stargazers!

Here are your Astronomy Skylights for the week of March 3rd, 2024 by Chris Vaughan. Feel free to pass this along to your friends and send me your comments, questions, and suggested topics. You can also follow me on Twitter as @astrogeoguy! Unless otherwise noted, all times are expressed in Eastern Time. To subscribe to these emails please click this MailChimp link.

If you’d like me to bring my Digital Starlab portable inflatable planetarium to your school or other daytime or evening event, or deliver a session online, contact me through AstroGeo.ca, and we’ll tour the Universe, or the Earth’s interior, together! My book with John A. Read entitled 110 Things to See With a Telescope is a guide to viewing the deep sky objects in the Messier List – for both beginners and seasoned astronomers. DM me to order a signed copy!

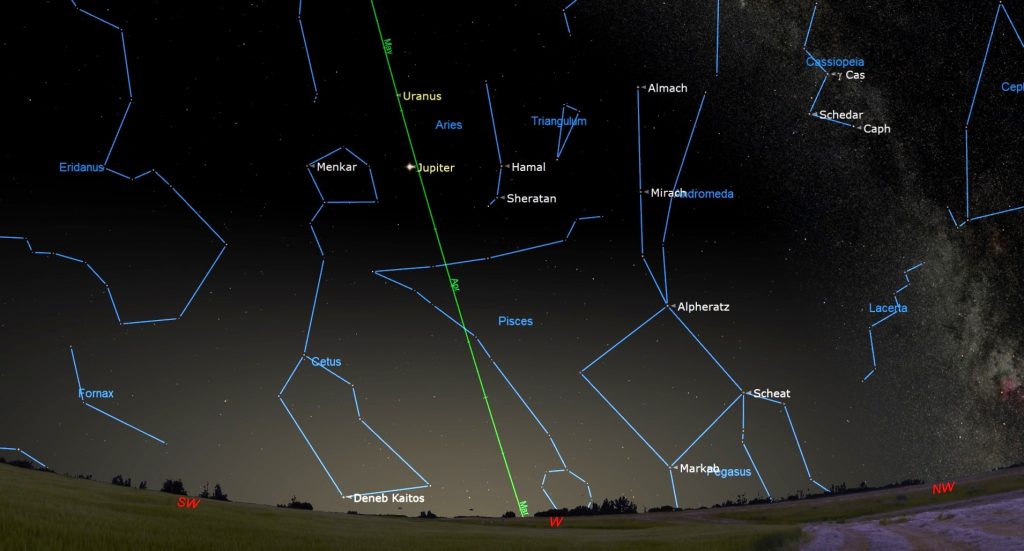

The moon will be sliding towards the morning sun this week, leaving the evenings nice and dark for viewing the best sights in the late winter sky, and for those interested in viewing all 110 deep sky objects in Charles Messier’s List. The bright planet Jupiter will dominate the western early evening sky with fainter Uranus, and brilliant Venus will gleam with fainter Mars above the eastern horizon before sunrise. Read on for your Skylights!

Evening Zodiacal Light

If you live in a location where the sky is free of light pollution, you might be able to spot a phenomenon called the zodiacal light from now until the new moon on March 10. After the evening twilight has faded, you’ll have about half an hour to check the western sky for a broad wedge of faint light extending upwards from the horizon and centered on the ecliptic below the planet Jupiter. That glow is the zodiacal light – sunlight scattered from countless small particles of material that populate the plane of our solar system. Don’t confuse it with the brighter Milky Way, which extends upwards from the northwestern evening horizon at this time of year. I posted a nice photo of it here.

The Moon

The moon will spend this week hanging out near the sun, leaving the evening and overnight sky free of moonlight for everyone on Earth.

The moon formally reached its third quarter phase this morning (Sunday) at 10:23 am EST or 7:23 am PST, which converts to 15:23 Greenwich Mean Time. Tonight, its nearly half-lit crescent will rise between the Teapot-shaped stars of Sagittarius (the Archer) and the curl of Scorpius (the Scorpion) during the wee hours and then linger into the lower part of the southern daytime sky until late morning. Each morning the moon will wane in phase. It will rise about an hour later and linger an hour longer into daytime.

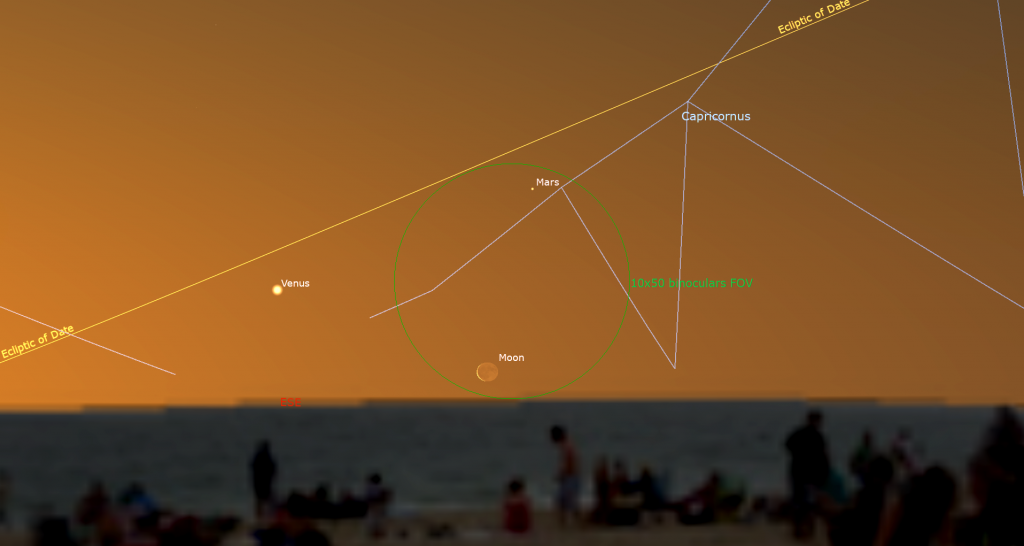

On Tuesday and Wednesday the moon will cross through the stars of Sagittarius. Then on Thursday morning before sunrise, early risers can catch sight of the pretty crescent moon shining to the right of brilliant Venus in a brightening sky above the southeastern horizon. The far fainter planet Mars will be between them, about a palm’s width from Venus towards the moon. To see Mars, you might need to use binoculars – or view their gathering from a southerly latitude.

The moon will hop closer to Venus on Friday morning, but it’ll be lower in the sky than the planet, so you may need to find an unobstructed vista to see it. Mars will perch less than a binoculars’ field of view above the moon – but point all optics away before the sun rises.

Friday will be our last glimpse of the old moon before it passes its new phase on next Sunday morning at 5:00 am EDT, 2:00 am PDT or 09:00 GMT. We’ll have switched to Daylight Saving Time a few hours before that. (I’ll share more about that next week.)

The Planets

This week, Jupiter’s brilliant dot will become visible about halfway up the western sky as things begin to darken after sunset. Plan to make your telescope viewing of Jupiter as soon as you can see the planet, while it’s higher in the sky and clearer in a telescope. Under steady air conditions, you’ll get reasonable views of Jupiter in any telescope until about 9 pm local time. Then the planet will set in the west around 11 pm local time. The bright stars of the winter constellations will be arrayed off to Jupiter’s upper left (or celestial southeast). Jupiter will be shuffling eastward through Aries (the Ram).

Any decent pair of binoculars can show you Jupiter’s four largest Galilean moons lined up on both sides of the planet. Named Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto in order of their orbital distance from Jupiter, those moons complete orbits of the planet every 1.7, 3.6, 7.2, and 16.7 days, respectively. If you see fewer than four moons, then one or more of them is crossing in front of or behind Jupiter, or hiding in Jupiter’s dark shadow – or two of the moons are very close together or occulting one another. All four moons will huddle close to Jupiter on next Sunday evening.

A small telescope will reveal Jupiter’s dark belts and light zones, which are aligned parallel to its equator. When Jupiter is descending in the west, those lines are tilted upright. With a better grade of optics, Jupiter’s Great Red Spot, a cyclonic storm that has raged for hundreds of years, is visible for several hours when it crosses the planet every 2nd or 3rd night. GRS appearances are fewer when the planet is only visible for a few hours each night. For observers in the Americas, the GRS will cross Jupiter’s disk in mid-evening Eastern Time on Monday, Thursday, and Saturday. The spot will appear later on Monday and Wednesday. The spot has been rather a pale pink in colour for some time now. If you have any coloured filters or nebula filters for your telescope, try enhancing the spot with them.

Blue-green Uranus is about 40 minutes behind Jupiter on the ecliptic. The magnitude 5.8 planet is quite easy to see in binoculars and backyard telescopes when the moon isn’t around. Look for Uranus less than a fist’s diameter to Jupiter’s upper left (or 7.9° to its celestial east). Uranus will also be positioned about two finger widths below the medium-bright star Botein. The bright Pleiades star cluster will sparkle a bit more than a fist’s width above Uranus (or 11.5° to its celestial northeast). Since Jupiter is closer to the sun than Uranus, its faster motion will carry it steadily closer to Uranus every night until they kiss in twilight on April 20.

Mercury, Saturn, and Neptune are all out of sight near the sun this week. Mercury will appear just above the western horizon after sunset towards the end of this week. The others will move into morning in the coming months.

Just as we will soon lose evening Jupiter to the sun’s glare, morning Venus will soon go away, too. This week the bright planet will rise at about 6 am local time, 45 minutes before sun. It will remain low until the brightening sky hides it. As I mentioned above, the old crescent moon will pay Venus a visit on Thursday and Friday. Much fainter Mars will be sliding a little farther from Venus’ upper right (or celestial west) every morning. Skywatchers living closer to the tropics will see Mars and Venus (and that old moon) more easily.

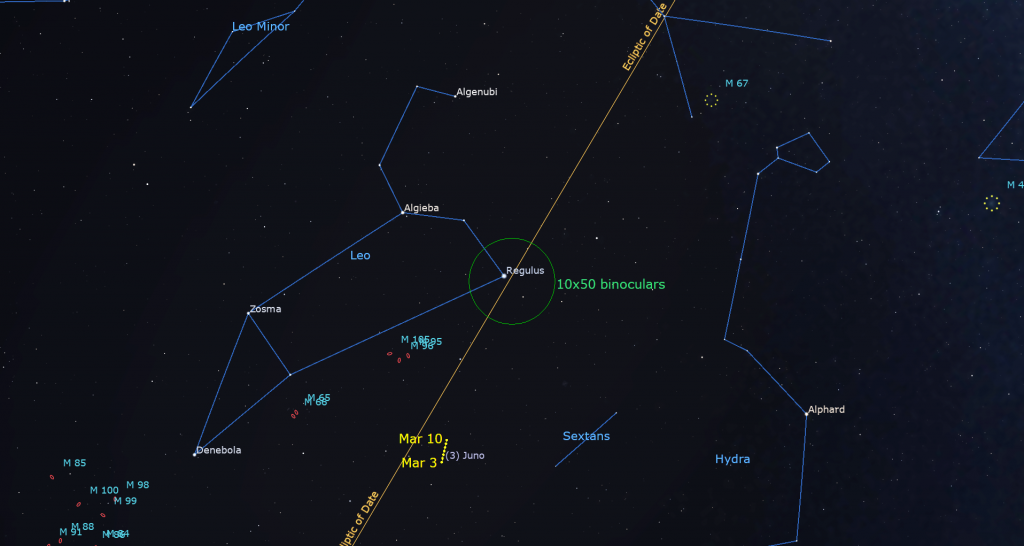

The major main belt asteroid named (3) Juno will reach opposition tonight (Sunday). At that time, Earth will be passing between the asteroid and the sun, minimizing our distance from Juno and causing it to appear at its brightest and largest for this year. The magnitude 8.7 object will be visible in backyard telescopes all night long. On opposition night, Juno will be positioned in a rather featureless part of the sky below (south of) the brightest stars of Leo – specifically, a slim fist’s diameter below the midpoint of the line connecting Regulus to Denebola. Those bright stars mark the lion’s chest and tail, respectively.

Stargazing Sights for Mid-March

With the moon vacating the evening sky, this week will be ideal for exploring the wonders of the dark sky in binoculars and backyard telescopes.

Once the sky becomes dark on a clear evening, head outside and look halfway up the northwestern sky for the distinctive W-shaped constellation of Cassiopeia (the Queen). A palm’s width to the left of her top star Segin you will find the Double Cluster. That pair of open star clusters, each 0.3 degrees across and approximately a finger’s width (or 0.45°) apart, form a spectacular one degree-wide sight in binoculars or a telescope at low magnification. (That’s twice the width of the full moon.) The lower, more westerly cluster, also known as NGC 869 is more compact, and contains more than 200 white and blue-white stars. NGC 884, the higher, easterly cluster, is slightly more spread out. The clusters reside in the Perseus Arm of the Milky Way and are located about 7,000 light-years from our sun. Their region of the sky is heavily loaded with opaque interstellar dust that makes the clusters dimmer than they really are.

The brightest star in Perseus (the Hero) is Mirfak or Alpha Persei (α Per). On March evenings, Mirfak gleams to the upper left of Cassiopeia (the Queen). Grab your binoculars! Mirfak’s golden light sparkles at the upper left (northwestern) edge of a large and loosely scattered cluster of about 100 hot, bright, blue-white B and A-class stars known as the Alpha Persei Moving Group, the Perseus OB Association, and Melotte 20. Those stars are siblings of Mirfak – born from the same molecular hydrogen cloud about 41 million years ago – and now travelling through the galaxy together with Mirfak. The open star cluster, which is sprinkled across 3 degrees of the sky, can be seen with unaided eyes, and looks wonderful in binoculars.

The constellation of Auriga (the Charioteer) is very high in the western sky during March evenings. The outer rim of our Milky Way galaxy passes directly through Auriga, so the constellation is rich in open star clusters that are visible as fuzzy patches with unaided eyes from dark sky locations. Binoculars and telescopes will readily show them in moderately light-polluted skies. The western (lower) region of Auriga contains the clusters NGC 1664, NGC 1778, and NGC 1857. The bright Starfish Cluster (or Messier 38 and NGC 1912), the nearby dimmer cluster NGC 1907, the bright Pinwheel Cluster (or Messier 36 and NGC 1960), and NGC 1893 are towards the centre of Auriga’s ring of stars. The bright open cluster called the Salt-and-Pepper Cluster (or Messier 37 and NGC 2099) sits above the ring’s upper left side. Another cluster named NGC 2281 is a fist’s diameter above the ring. How many of these patches of stars can you see?

Taurus (the Bull) hosts the Pleiades open star cluster, also known as the Seven Sisters and Messier 45. It is located in the western sky about two fist diameters above Jupiter. Visually, the cluster is made up of young, hot blue stars with the names Asterope (“as-ter-OH-pea”), Merope, Electra, Maia, Taygeta, Celaeno, and Alcyone. They are indeed related – born of the same primordial gas cloud. In Greek mythology, they were the daughters of Atlas, and half sisters of the Hyades (the triangular patch of stars that form the bull’s face).

To the unaided eye, only six of the “sister” stars are usually seen; their parents, the stars Atlas and Pleione, are huddled together at the east end of the grouping. Under magnification, hundreds of stars appear with them. Not surprisingly, many cultures, including Aztec, Maori, Sioux, Hindu, and more, have noted this object and developed stories around it – usually interpreting it as a hole in the sky or the portal to the afterlife. In Japan, it is called Suburu, and forms the logo of the eponymous car maker. Due to its shape, some people mistake the Pleiades for the Little Dipper.

The large, but not-very-bright constellation of Monoceros (the Unicorn) occupies the southern sky to the left (celestial east) of Orion (the Hunter). The unicorn fills the sky between the bright stars Procyon and Sirius. Often overlooked, this constellation straddles the winter Milky Way. Among its many treasures is the spectacular Rosette Nebula and the star cluster (NGC 2244 and NGC 2238) that sits inside it. The big rose is quite easy to see in binoculars. Aim them about a fist’s diameter to the left of Orion’s bright, reddish star Betelgeuse. Monoceros is also home to the Christmas Tree Cluster (NGC 2264) and its associated nebulosity, the Double Wedge Cluster (NGC 2232), and the spectacular triple star Beta Monoceros, which sits a fist’s diameter to the upper right (or 10° to the celestial north) of much brighter star Sirius.

Messier Marathon Weekend is Coming!

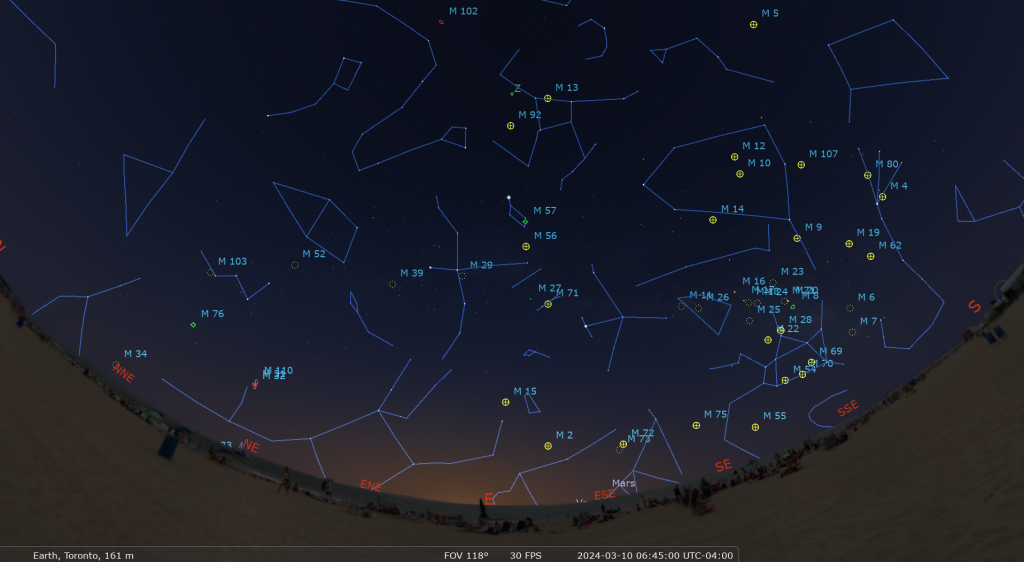

Charles Messier’s list of the best and brightest showpieces in the night sky is popular with astronomers of all experience levels. During the new moon periods in early spring each year, it’s possible for lovers of deep sky objects (nebulae, galaxies, and clusters) who live anywhere on Earth between latitudes 20° south and 55° north to observe every one of the 110 objects on Messier’s list within a single night. For many amateur astronomers, this observing challenge is a bucket list item known as the Messier Marathon. This coming weekend is your first chance for 2024!

The Messier List (or catalog) objects are designated by their “M-codes”, M1 through M110 (or Messier 1 through Messier 110). Astronomers commonly refer to the group as the Messiers. Most of these famous objects also have proper names, such as the Whirlpool Galaxy (M51), the Pleiades (M45), and the Beehive Cluster (M11).

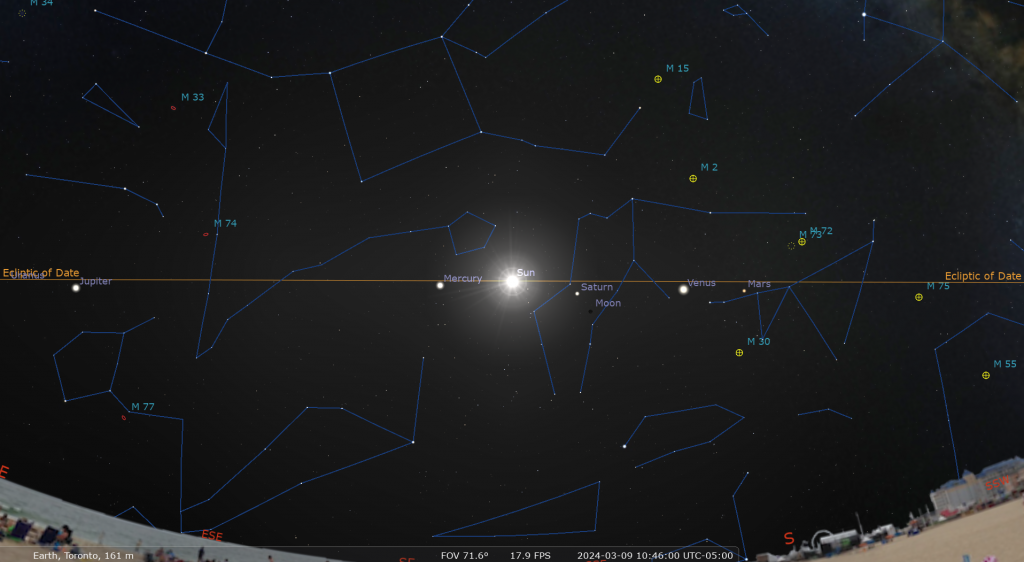

The objects in the list are distributed throughout the night sky visible from mid-northern latitudes. (Messier and his contemporaries observed them from Paris in the mid 18th Century.) None of the objects reside in the stars between Pisces and Aquarius, so when the sun’s trip along the ecliptic carries it between those two constellations in March every year, it allows us to see all of the Messier objects between dusk and dawn. The idea of a running a “Messier Marathon” originated in 1979 with another comet hunter, Californian Don Machholz, and others. Sadly, Don passed away in 2022. More info about him is at https://donmachholz.com/.

To see the fainter Messiers, we need a night within a day or two of the new moon, which occurs overnight this Saturday, March 9. A clear sky all night long is a must, so check the forecast and choose the night that offers the best conditions. If more than one night looks promising, make your attempt on the first night, so you have the option for a second try. This year, April 6 is a back-up date.

Pick a site free from direct lights and light pollution, with open sightlines to the horizon, especially to the west and the southeast. To improve your site selection, use a star chart, planisphere, or astronomy app to preview where the objects will be, especially the ones that will be observed when they’re near the horizon. A site at higher elevation will also give you more time to observe the low objects. Bring warm clothes, and stock up on snacks and drinks – you’ll be awake all night!

Many Messier objects are visible in binoculars – 10×50 models offer a good compromise between weight and performance. The dimmer objects will require a telescope. A 3-inch diameter (80 millimeter) telescope will work under very dark sky conditions, but a larger aperture telescope will make the job easier. Low power, wide field of view eyepieces are recommended. Be sure to set up your telescope, and organize your other equipment, well before sunset.

To start your marathon, you will need to quickly catch the objects that set in the west after sunset – specifically the dim galaxies M77 and M74. By the time the sky has grown dark enough to see these galaxies, they will be nearing the horizon. It’s a good idea to limit the time spent on the first galaxy so as not to miss the other one. Immediately after viewing those two, you’ll look for M33, the large face-on spiral galaxy in the constellation of Triangulum (the Triangle), and then the Andromeda Galaxy trio of M31, M32, and M110.

From this point, you will have time to work your way systematically across the sky from west to east. As you do so, more objects will rise in the east. By late evening, you should arrive at the Virgo Cluster of galaxies. When you have viewed the 17 objects there, you can take a break until the next group of Messiers rises into view at around 3 am local time. Here’s a website with a recommended viewing order. The objects aren’t ordered simply by their setting time, because brighter objects can be picked out during twilight, while dimmer objects need a darker sky. (Be careful not to confuse the viewing order with the Messier number.)

The final wave of objects includes M55, M75, M72, M73, and M2, which rise in the pre-dawn. The last Messier is the globular cluster M30, which will rise in the east as dawn starts to break – so it will be a challenge to see this object. Observers in southerly latitudes will have an advantage because the sun rises and sets more vertically, giving them a shorter twilight period. Observers near the latitude of Toronto will probably not be able to see M30 this year. Several friends will join me at my local rural observatory to make the attempt this year. Fingers crossed!

Several astronomy organizations will recognize your achievement if you observe all of the Messier objects – and they don’t require you to do it in one night. The Royal Astronomical Society of Canada will issue an RASC Messier Certificate to members who complete the list and provide documentation. The society recognizes both the computerized Go-to telescope and manual approaches. The USA-based Astronomical League will send a Messier Program Certificate to members-at-large or members of affiliated astronomical societies who provide observational notes for 70 objects found without a Go-to telescope. The organization will send a lapel pin and honorary membership certificate for completing the entire list (over any time frame). Both groups’ websites have information and observing forms to download and print out.

Good luck! If you’d like more details, I’ve published additional Messier Marathon information in Space.com’s Run the ‘Messier Marathon’ to Finish This Astronomical Bucket List and SkyNews magazine’s ‘Running’ the Messier marathon. More marathon planning links include The Messier Marathon Planner by Larry McNish and Rob’s Guide to the Messier Marathon.

Walking the Dog’s Stars

If you missed my information about the night sky’s brightest star Sirius and my tour of its home constellation of Canis Major (the Big Dog), I posted it with sky charts and pictures here.

Public Astronomy-Themed Events

Every Monday evening, York University’s Allan I. Carswell Observatory runs an online star party – broadcasting views from four telescopes/cameras, answering viewer questions, and taking requests! Details are here. They host in-person viewing on the first clear Wednesday night each month. Other Wednesdays they stream views online via the observatory YouTube channel. Details are here.

On Wednesday evening, March 6 at 7:30 pm EDT, the RASC Toronto Centre will host their free, public, in-person monthly Recreational Astronomy Night Meeting in the Gemini East Room at the Ontario Science Centre. The meeting will also be live streamed at https://www.youtube.com/rasctoronto/live. Talks include The Sky This Month, analyzing asteroids, and How to Photograph Eclipses: Solar and Lunar. Details are here.

On Saturday, March 9 from 10 am to noon, you can try out Solar Observing at the Ontario Science Centre! If it’s sunny, members of the RASC Toronto Centre will be setting up outside on the Teluscape in front of the main doors. They’ll have an array of special equipment designed to view the Sun safely. This is free to the public, but parking and admission fees inside the Science Centre will still apply. Check the RASC Toronto Centre website or their Facebook page for the Go or No-Go notification.

Keep your eyes on the skies! I love getting questions and requests. Send me some!