Diwali Details, Mercury Meets Mars, the Waxing Moon Passes Planets, Letters on Luna, and Taurids Tempt Us!

An image of the moon by Michael Watson of Toronto, taken five hours after reaching first quarter on November 7, 2016 . More of Michael’s moon images can be enjoyed at https://www.flickr.com/photos/97587627@N06/albums/72157634160736057

Welcome to the Darker skies of November, Stargazers!

Here are your Astronomy Skylights for the week of November 7th, 2021 by Chris Vaughan. Feel free to pass this along to your friends and send me your comments, questions, and suggested topics. You can also follow me on Twitter as @astrogeoguy! Unless otherwise noted, all times are expressed in Eastern Time. To subscribe to these emails please click this MailChimp link.

I can bring my Digital Starlab portable inflatable planetarium to your school or other daytime or evening event, or teach a session online. Contact me through AstroGeo.ca, and we’ll tour the Universe, or the Earth’s interior, together! My terrific new book with John A. Read entitled 110 Things to See With a Telescope is a guide to viewing the deep sky objects in the Messier List – for both beginners and seasoned astronomers. DM me to order a copy!

I describe Diwali’s astronomy. The moon will dominate the evening sky worldwide this week as it waxes through first quarter and sports a Lunar X and V for the Americas. Three bright planets will shine in evening, and Mercury will brush past Mars in the pre-dawn. Meanwhile, Taurus will emit some meteors while Ceres crosses its V-shaped face. Read on for your Skylights!

Falling Back

Did you remember to set your clocks back an hour last night? With the end of Daylight Savings Time, we’re back to our regularly scheduled program of sunrises and sunsets. Your time zone abbreviation has changed, too. For example, 8 pm Eastern Daylight Time (EDT) is now 7 pm Eastern Standard Time (EST).

For those of us in Toronto, the sun is rising at about 7 am EST and setting at 5 pm EST. The amount of daylight is decreasing by a whopping 2.5 minutes every day – or 18 minutes every week! The end of astronomical twilight, when the sun is far enough below the horizon for the sky to reach maximum darkness, ends at about 6:38 pm. As a stargazer, I do appreciate being able to pull out the telescope earlier – but I’m not a fan of the colder temperatures and the cloudier skies of November.

By the way, if you plan to use your telescope on chilly nights, place it in a secure spot outside, with the lens cap on, at least an hour before you head out. That will give the air inside it a chance to equalize with the outside temperature – yielding sharper views through it. Before you bring it back in, put the lens caps back on to keep the optics from frosting up – or zip it into its case, if you have one. (Or snug a garbage bag around it while it warms to room temperature.)

Happy Diwali!

Like many traditional observances around the world, the timing of the South Asian festival of Diwali, or the Festival of Lights, has an astronomical connection. Diwali, which commenced last Thursday, November 4 and lasts five days, always begins just before the new moon phase that falls between mid-October and mid-November – dubbed “the darkest night of the year”. Diwali celebrates the triumph of good over evil after the fall harvest. The festival’s name arises from the Sanskrit expression deepa avali, or “rows of lighted clay lamps” – which were set outside when there was no moon to light the way at night.

The Hindu lunisolar calendar employs twelve 30-day months within a 360-day year. To avoid calendar drift caused by its annual five day shortfall, it adds an extra (intercalary) month every two or three years, in a pattern that repeats every 19 years. Months commence at the full moon, and are followed by a “bright” fortnight. Each mid-month’s new moon kicks off a “dark” fortnight. The Hindu new year begins around the March equinox. The Hindu month that commences around mid-October on the Gregorian calendar is named Kartik or Kartika.

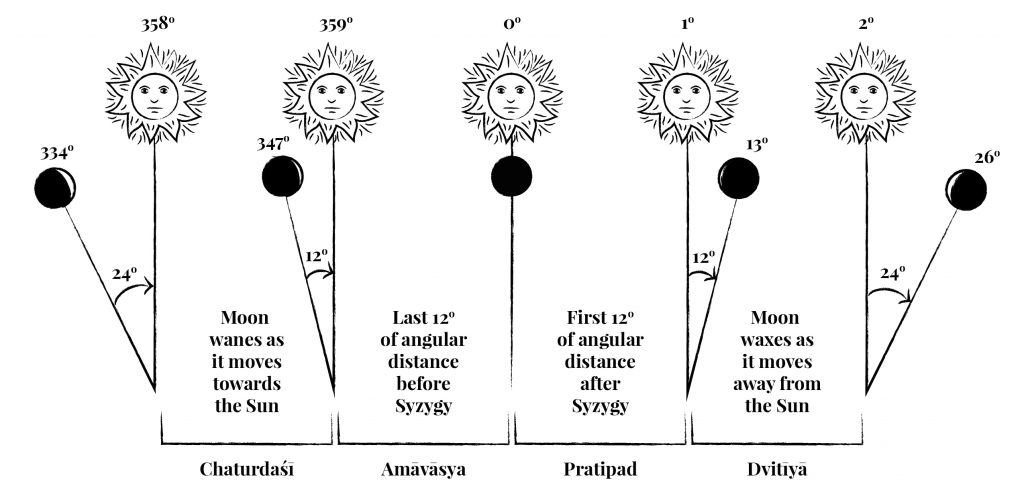

During its orbit around Earth, the moon varies its angle from the sun by about 12 degrees per day, resulting in 30 unique phases, half of them waxing and the other half waning. Each day of the Hindu lunar month is called a tithi, with each tithi bearing a name associated with a particular illuminated phase. On the day before new moon (or syzygy), the moon is less than 12 degrees west of the sun, and appears as a slim waning crescent. That tithi is called Amāvásyā (Sanskrit: अमावस्या), which literally translates to “no moon there”, since it’s rarely observable. The tithi for the day following new moon (slim waxing crescent) is Pratipada. Diwali always commences on Amāvásyā, the 15th day of Kartika.

Northern Taurids Meteor Shower

The Southern Taurids meteor shower, which reached its maximum rate of about 5 meteors per hour last Thursday, will now taper off until December 2.

Meteors from the Northern Taurids meteor shower, which appear worldwide from October 13 to December 2 annually, will reach a maximum rate of about 5 per hour from Thursday night to Friday morning, November 12. The long-lasting, weak shower is the second of two consecutive showers derived from debris dropped by the passage of periodic Comet 2P/Encke. The larger-than-average grain sizes of the comet’s debris often produce colorful fireballs.

The best viewing time for Northern Taurids will fall around 1 am local time on Friday, when the shower’s radiant, located in northwestern Taurus near the Pleiades star cluster, will be highest in the southern sky. (When a shower’s radiant is lower, many of its meteors are hidden below your local horizon.)

At this year’s peak, a first quarter moon will set by midnight, allowing more meteors to be seen after that. While you are looking up, keep an eye out for early meteors of the Leonids shower. They’ll appear to be traveling from east to west across the sky. That shower will peak next week on November 17-18.

The Moon – with Bonus Letters!

For the next two weeks the moon will be of particular interest! This week, we’ll see a Lunar X, and next week will bring a partial lunar eclipse!

Tonight (Sunday, November 7) in the southwestern sky after sunset, the young crescent moon will shine several finger widths to the lower right (or 5 degrees to the celestial west) of the very bright planet Venus – close enough for them to share the field of view in binoculars. The duo will set at about 7 pm local time. Hours later, in midday on November 8, observers in parts of northeastern Asia and the western Aleutian Islands can see the moon pass in front of, or occult, Venus. (Surrounding regions will only see the moon pass very close to that planet.)

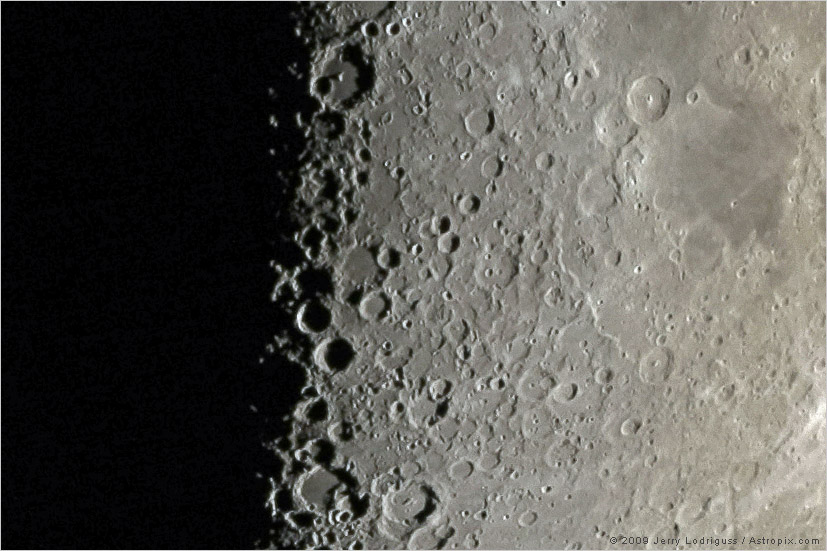

On Monday and Tuesday night, the moon’s crescent will grow a little thicker as the moon sidles eastward through the constellation of Sagittarius (the Archer). The moon will also linger longer in the evening sky than Venus. This week will be an ideal time to view the moon in binoculars and small telescopes during early evening. That’s because the sunlight striking the moon along the pole-to-pole terminator is nearly horizontal – casting deep, black shadows to the west of every bump, hill, mountain, and crater rim. As the moon’s angle from the sun increases each night, the terminator shifts west, highlighting new vistas. Look often!

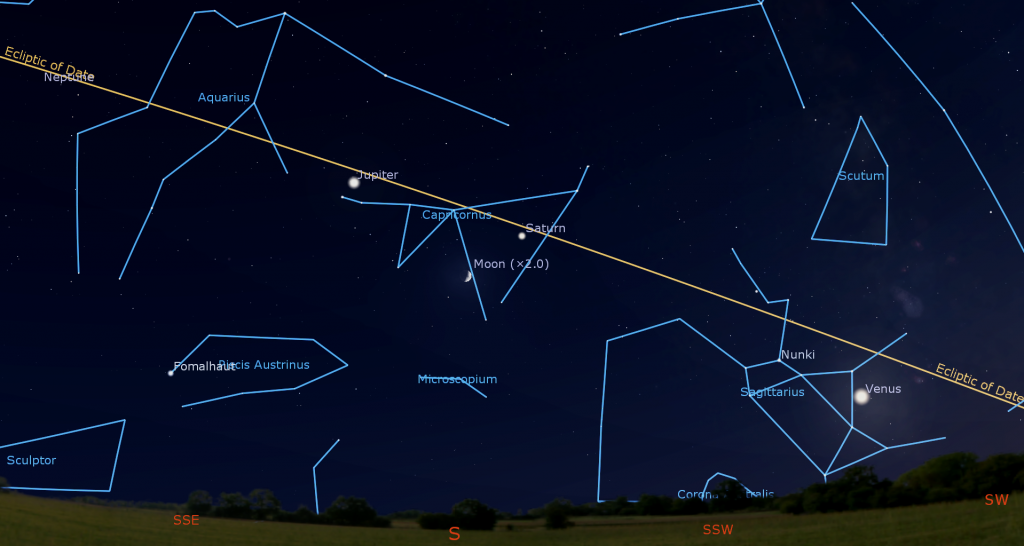

This week will also feature the moon’s monthly trip past the bright gas giant planets Jupiter and Saturn! On Tuesday, the 33%-illuminated moon will shine a fist’s diameter to the lower right (or 11° to the celestial southwest) of Saturn, with brighter Jupiter off to their upper left. On Wednesday night, the moon will hop to sit below and between those two planets, and close enough to show Saturn and the moon together in binoculars. It’ll also be a nice wide-field photo opportunity. On Thursday night, the 55%-illuminated moon will sit less than a palm’s width below (or 5° south of) Jupiter – close enough for them to share the field of view in binoculars. If you are able to photograph the trio on one, two, or three of the nights, let me know! The moon will bid adieu to the bright planets after Thursday, until it visits them again on December 7-9.

Also on Thursday, the moon will complete the first quarter of its journey around Earth at 7:46 am EST or 12:46 Greenwich Mean Time. At first quarter phase, its 90 degree angle from the sun will cause us to see the moon exactly half-illuminated – on its eastern side. At first quarter, the moon always rises around mid-day and sets around midnight, so it is also visible in the afternoon daytime sky.

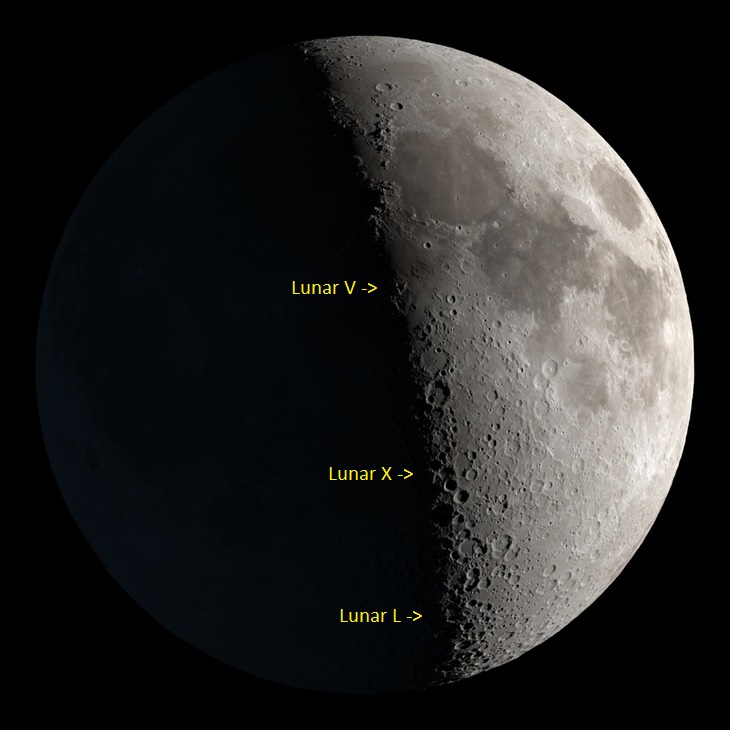

Several times a year, for a few hours near its first quarter phase, a feature on the moon called the Lunar X becomes visible in powerful, tripod-mounted binoculars and any size of backyard telescope. When the rims of the craters Purbach, la Caille, and Blanchinus are illuminated from a particular angle by the sun, they form a small, but very obvious X-shape.

The phenomenon is an example of pareidolia – the tendency of the human mind to see familiar objects when looking at random patterns. The Lunar X is located near the terminator, about one third of the way up from the southern pole of the moon (at lunar coordinates 2° East, 24° South). A prominent round crater named Werner sits to its lower right (or lunar southeast).

During a Lunar X event, you can also look for the Lunar V and the Lunar L. The “V” is produced by combining the small crater named Ukert with some ridges to the east and west of it. It is located a short distance above the moon’s equator at lunar coordinates 1.5° East, 8° North. For a further challenge, see if you can see the letter “L” down near the moon’s southern pole. Its position is to the southwest of three prominent and adjoining craters named Licetus, Cuvier, and Heraclitus which, in combination, resemble Mickey Mouse’s head and ears. In some photographs, a backwards “E” shows above the “L”, allowing you to spell out “L-O-V-E” by using any round crater!

On Thursday, November 11 the lunar letters are predicted to start developing at around 5 pm EST (or 22:00 GMT), peak in intensity around 7 pm EST (or 00:00 GMT on Friday), and then disappear within two hours. The phenomenon will be observable anywhere on Earth where the moon is visible, especially in a dark sky, between about 22:00 GMT on November 11 and 02:00 GMT on November 12.

On Friday and Saturday, the waxing gibbous moon (i.e., more than half-illuminated) will journey through the dull stars of Aquarius (the Water-Bearer). Saturday night’s bright moon will shine a few finger widths below distant, dim Neptune – but that’s not the preferred circumstance for seeing the magnitude 7.85 blue planet.

Those same nights, the terminator will be positioned to the left (or lunar west) of Rupes Recta, also known as the Lunar Straight Wall. The feature is very obvious in a backyard telescope. The rupes, Latin for “cliff”, is a north-south-aligned fault scarp that extends for 110 km across the southeastern part of Mare Nubium, the Sea of Clouds. That’s the large, dark region located in the lower third of the moon’s Earth-facing hemisphere. The Straight Wall is always prominent a day or two after first quarter, and shows well again just before third quarter. For reference, the Straight Wall is located above (to the lunar north) of the bright, prominent crater Tycho, which is famous for its lengthy and arrow-straight rays extending across much of the moon’s disk. That ray system is composed of material blasted out when Tycho was formed. (Tycho will be partly shadowed on Friday.)

The moon will end this week swimming between the aquatic constellations of Cetus (the Whale) and Pisces (the Fishes).

The Planets

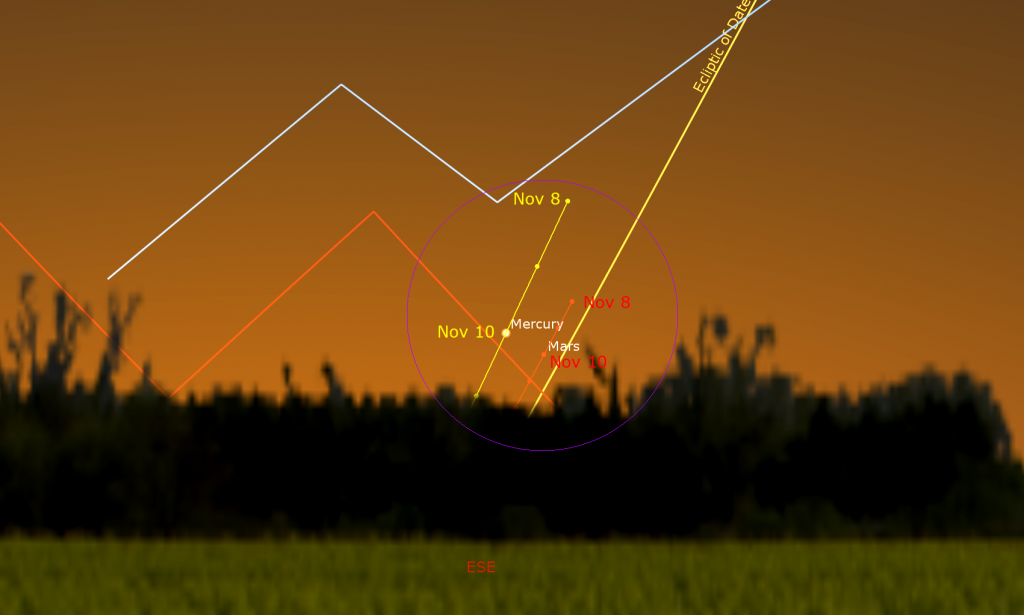

The pre-dawn sky will host a close conjunction of Mercury and Mars this week. Look just above the east-southeastern horizon before sunrise on Wednesday morning, November 10 to see Mercury situated less than a finger’s width to the upper left (or 57 arc-minutes to the celestial north) of Mars. You’ll need access to an unobstructed horizon and haze-free skies to see them. For this conjunction Mars will appear one-tenth as bright as magnitude -0.9 Mercury. In mid-northern latitudes, the best viewing time will be around 6:30 am local time, when the two planets will sit a few degrees above the horizon, in a brightening sky. The duo will be close enough to appear together in the field of view of a low-magnification backyard telescope from Tuesday to Thursday, and will be binoculars-close from November 5 to 15 – but be sure to turn your optical aids away from the eastern horizon well before the sun rises. Tropical latitude observers will see the two planets more easily – higher and in a darker sky.

Mercury will be descending sunward all week long, and will disappear into the sun’s glare by week’s end. Meanwhile, even though Mars is also traveling east compared to the background stars, the red planet is increasing its angle from the sun by Earth’s motion. Mars is just beginning a year-long journey to a bright showing at opposition in December, 2022.

The rest of the planets are in the evening sky nowadays. This week, Venus will set in the southwest at about 7:25 pm local time. Venus’ position well below (south of) a canted-over evening ecliptic will keep the magnitude -4.7 planet low in the sky for mid-northern latitude observers until later in the month. You might even need to walk around to find a view of the planet between the trees or buildings after sunset.

Viewed in a telescope, Venus will appear half-illuminated, on its sun-facing side. Aim your telescope at Venus as soon as you can spot the planet in the sky (but ensure that the sun has completely disappeared first). That way, the planet will be higher and shining through less distorting atmosphere – giving you a clearer view of it. A light sky will also allow Venus’ shape to be seen more readily. The planet will grow in size and wane in phase every week for the rest of this year because Venus will be traveling into the space between Earth and the sun.

Jupiter and Saturn are both moving eastward through the stars at the opposite sides of the constellation of Capricornus (the Sea-Goat) – but not faster than the nightly sky migrates west. The two planets will get close to Venus during December. For now, Jupiter’s bright, white dot will become visible, sitting less than a third of the way up the south-southeastern sky, a short time after dusk. 18 times fainter Saturn will appear, parked 1.5 fist diameters to the right (or 15.5° to the celestial west) of Jupiter, once the sky darkens a bit more. They’ll reach their highest elevation in the sky, over the southern horizon, at around 6:15 pm local time – and then set in the west before midnight.

Saturn and its beautiful rings are visible in any size of telescope. If your optics are sharp and the air is steady, try to see the Cassini Division, a narrow gap between the outer and inner rings, and a faint belt of dark clouds encircling the planet. Remember to take long, lingering looks through the eyepiece – so that you can catch moments of perfect atmospheric clarity.

From here on Earth, Saturn’s axial tilt of 26.7° lets us see the top of its ring plane, and allows its brighter moons to array themselves all around the planet. Saturn’s largest and brightest moon Titan never wanders more than five times the width of Saturn’s rings from the planet. The much fainter moon named Iapetus can stray up to twelve times the ring width during its 80-day orbit of Saturn. The next brightest moons Rhea, Dione, Tethys, Enceladus, and Mimas all stay within one ring-width of Saturn.

During this week, Titan will migrate counter-clockwise around Saturn, moving from the upper left (celestial northeast) of Saturn tonight to below (celestial south of) Saturn next Sunday. (Remember that your telescope will probably flip the view around.) How many of the moons can you see in your telescope?

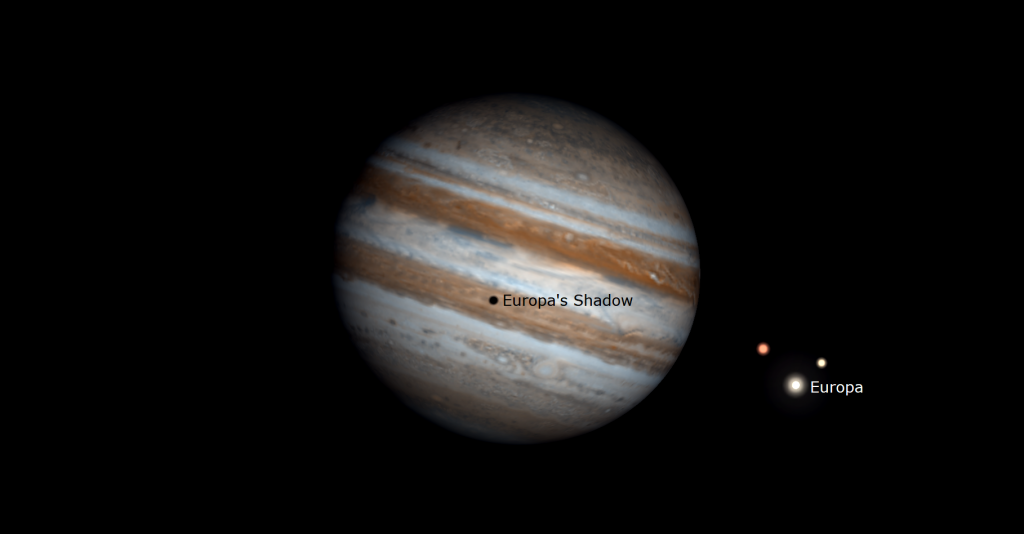

Binoculars and small telescopes will show you the Jupiter’s four large Galilean moons named Io, Europa, Callisto, and Ganymede. Since Jupiter’s axial tilt is a miniscule 3°, those moons always look like beads strung on a line that passes through the planet, and parallel to Jupiter’s dark equatorial belts. That line of moons, and the belts, tilt as Jupiter crosses the sky. The moons’ arrangement varies from night to night. Io, for example, orbits Jupiter once every 42 hours. From one night to the next night, 24 hours has elapsed on Earth – time for Io to complete half an orbit and shift from one side of Jupiter to the other. The other Galilean moons move less rapidly, taking between 3.5 and 16.7 days to orbit Jupiter.

For observers in the Eastern Time Zone with good telescopes, the Great Red Spot (or GRS) will be visible while it crosses Jupiter after dusk tonight (Sunday), on Tuesday, and next Sunday, and in mid-evening on Monday, Thursday, and Saturday.

From time to time, the small, round, black shadows cast by Jupiter’s Galilean moons become visible in amateur telescopes when they cross (or transit) the planet’s disk. On Monday night, November 8 Europa’s shadow will cross Jupiter from 5:30 pm to 8:05 pm EST. On Friday night, November 12 Io’s small shadow will cross Jupiter from 8 pm to 10:10 pm EST.

Uranus reached opposition on Friday – so it’s still close to its minimal distance from Earth this week, shining at a peak brightness of magnitude 5.65 and appearing slightly larger in telescopes. Look for the planet’s small, blue-green dot moving slowly retrograde westwards in southern Aries (the Ram), a fist’s width below (or 11.5 degrees southeast of) that constellation’s brightest stars, Hamal and Sheratan. Or use binoculars to locate Uranus using the nearby star Mu Ceti. It’s also about 1.6 fist diameters to the upper right (or 16 degrees to the celestial west-southwest) of the Pleiades star cluster. This week Uranus will be observable all night long – especially after midnight, when it will have climbed more than halfway up the southeastern sky. But the bright moon will be swinging closer to it by the weekend.

Distant, dim Neptune is in the sky all night long, near the border between Aquarius (the Water-Bearer) and western Pisces (the Fishes) – and nearly three fist diameters to the left (or celestial east) of Jupiter. The moon will pass close to it on Saturday, so look for the magnitude 7.85 planet early this week. The main belt asteroid named (2) Pallas is not far away. This week, Pallas will be traveling slowly downward (or southward) through Aquarius, a few finger widths below (celestial southwest of) the medium-bright star Hydor.

See Ceres

The orbital motion of the dwarf planet named (1) Ceres is carrying it directly through the Hyades, the large open star cluster that forms the V-shaped face of Taurus (the Bull). Magnitude 7.6 Ceres is bright enough to see in a backyard telescope. Tonight (Sunday), Ceres, will be positioned only a finger’s width to the upper right (or 49 arc-minutes west) of the very bright star Aldebaran. For the rest of this week, Ceres will travel westward toward the centre of the bull’s face.

The Water Constellations – The Lucky Stars of Aquarius

If you missed last week’s story and tour through Aquarius (the Water-Bearer), I posted it with some photos of its splendors here.

Public Astro-Themed Events

Every Monday evening, York University’s Allan I. Carswell Observatory runs an online star party – broadcasting views from four telescopes/cameras, answering viewer questions, and taking requests! Details are here. Their in-person Wednesday night viewing has been converted to online via the observatory YouTube channel.

My free, family-friendly Insider’s Guide to the Galaxy webcasts with Jenna Hinds of RASC National returns on Tuesday, November 9 when we’ll cover viewing the moon’s geology and the upcoming Lunar X and partial lunar eclipse events. You can find more details and the schedule of future sessions here.

On Tuesday evening, November 9 from 7 to 8:30 pm EST, the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada will stream their latest free public speakers series presentation, The James Webb Space Telescope: Canada’s Role in the Exploration of the Universe. The panelists will be Dr. Jean Dupuis, a senior mission scientist in space astronomy at the Canadian Space Agency (CSA), and Dr. Nathalie Ouellette, astrophysicist and science communicator, coordinator of the Exoplanet Research Institute at the Université de Montréal, and the scientific coordinator for the James Webb Space Telescope in Canada. You can join the session on Zoom or watch it on YouTube. Details are here.

In-person sessions at the David Dunlap Observatory may not be running at the moment, but RASC are pleased to offer some virtual experiences instead, in partnership with Richmond Hill. The modest fee supports RASC’s education and public outreach efforts at DDO. On Saturday night, November 13 from 8:30 to 10 pm EDT, tune in for Up in the Sky. During the family-friendly session, RASC astronomers will live-stream views through their telescopes and the giant 74” telescope at DDO (pre-recorded views will be used if skies are cloudy). Only one registration per household is required. Deadline to register for this program is Wed., November 10, 2021 at 3 pm. Prior to the start of the program, registrants will be emailed the virtual program links. The registration link is here.

On Sunday afternoon, November 14 from 1 to 2 pm EDT, join me for Ask an Astronomer. During these family-friendly sessions, I’ll answer your questions about the universe and review what’s up nowadays. Only one registration per household is required. Deadline to register for this program is Wed., November 10, 2021 at 3 pm. Prior to the start of the program, registrants will be emailed the virtual program links. The registration link is here.

Don’t forget to take advantage of the astronomy-themed YouTube videos posted by RASC Toronto Centre and RASC Canada.

Keep looking up, and enjoy the sky when you do. I love questions and requests. Send me some!