Early Aquariids Meteors, Daytime Moon Joins Jupiter, Space Telescope and Summer Milky Way Sights to See!

A comparison of images of Stephan’s Quintet of galaxies in Pegasus, taken in infrared by the James Webb Space Telescope in 2022 (left) and the visible and near-infrared wavelengths by the Hubble Space Telescope in 2009 (right). The spiral galaxy at left is NGC 7320. It is only 40 million light-years away. The rest of them are about 290 million light-years away.

Hello, mid-July Stargazers!

Here are your Astronomy Skylights for the week of July 17th, 2022 by Chris Vaughan. Feel free to pass this along to your friends and send me your comments, questions, and suggested topics. You can also follow me on Twitter as @astrogeoguy! Unless otherwise noted, all times are expressed in Eastern Time. To subscribe to these emails please click this MailChimp link.

If you’d like me to bring my Digital Starlab portable inflatable planetarium to your school or other daytime or evening event, or deliver a session online, contact me through AstroGeo.ca, and we’ll tour the Universe, or the Earth’s interior, together! My terrific new book with John A. Read entitled 110 Things to See With a Telescope is a guide to viewing the deep sky objects in the Messier List – for both beginners and seasoned astronomers. DM me to order a signed copy!

The moon will only shine after midnight this week as it wanes through third quarter, occults a bright star, and points to Jupiter in daytime. Moonless evening skies worldwide allow us to see Comet K2 and the delights in the summer Milky Way. I highlight the objects from the recent JWST image release that we can see for ourselves. The midnight-to-dawn string of bright planets continues and a few meteors should appear. Read on for your Skylights!

Southern Delta Aquariids Meteor Shower

The Southern Delta Aquariids meteor shower will begin around Thursday this week. The annual event, which runs from July 21 to August 23, is caused when the Earth passes through a cloud of tiny particles dropped by a periodic comet – likely Comet 96P/Machholtz. The shower will peak overnight on Friday-Saturday, July 29-30, but is especially active for a week surrounding that date. This shower commonly generates 15-20 meteors per hour at the peak, but is best seen from the southern tropics, where the shower’s radiant, in Aquarius (the Water-Bearer), is positioned higher in the sky. No moonlight will spoil the show this year. I’ll share some meteor shower tips next week.

The Moon

The moon will spend this week in the post-midnight sky, swimming through the aquatic constellations there as it wanes in phase and lingers into morning daylight. That will leave evenings worldwide nice and dark to enjoy summer meteors and deepsky delights.

Tonight (Sunday) the 74%-illuminated moon will rise around midnight among the stars at the border shared by Aquarius (the Water-Bearer), Pisces (the Fishes), and Cetus (the Whale). The bright point of light to the moon’s left (or celestial northeast) will be Jupiter. The moon and the planet will be carried into the southern sky as around the time that the sunrise hides Jupiter. On Monday night, the moon’s eastward orbital motion will shift it to sit several finger widths below (or 3 degrees to the celestial southeast of) the bright dot of Jupiter – easily close enough for them to share the view in binoculars. On Tuesday morning the moon will remain visible in the morning daytime sky, allowing you to seek out Jupiter in daylight by positioning the moon towards the left of your binoculars’ field of view. The moon will be steadily moving farther from Jupiter, so try to view them before mid-morning. Once you see Jupiter, try finding its bright pinpoint with your unaided eyes.

For the rest of the week, the moon won’t clear the rooftops until well after midnight, but then it will remain visible in the daytime sky until mid-day. In the wee hours of Wednesday, look for reddish Mars shining to the moon’s lower left and Jupiter to its upper right. If you have an unobstructed view of the eastern horizon, you can watch the moon pass in front of (or occult) the medium-bright star named Mu Piscium after midnight on Tuesday (i.e., Wednesday morning). The start time (or ingress) and the end time (or egress) vary by latitude. For the Greater Toronto Area, the leading edge of the moon will cover the star at 12:49 am EDT. The star will re-appear from behind the opposite, dark limb of the moon at 1:44 am. Binoculars or any size of telescope will show the event nicely. Be sure to start looking a few minutes before the times I’ve given. You can check the visibility for your own location by using the free online tool Stellarium Web.

The moon will officially complete three quarters of its orbit around Earth, measured from the previous new moon, on Wednesday, July 20 at 10:19 am EDT or 7:19 am PDT and 14:19 Greenwich Mean Time. At the third (or last) quarter phase the moon appears half-illuminated, on its western, sunward side. Serious sky-watchers consider the third quarter moon as the kick-off for their observing campaigns, since the evenings will be darkest from then until the end of July.

On Thursday morning, the now-waning crescent moon will shine several finger widths to the upper right (or 4 degrees to the celestial WSW) of Mars’ reddish dot in southern Aries (the Ram) – cosy enough to share the view in binoculars. By the time the sky begins to brighten around 5 am, the moon and Mars will be halfway up the southeastern sky. On Friday morning, the moon will hop to sit to Mars’ lower left (celestial east). In the interim, observers in eastern China, Japan, and northeastern Russia can watch the moon occult Mars around 15:00 GMT. Friday morning’s moon will also be poised just a finger’s width to the lower left (or 1° to the celestial east) of Uranus. Look for the planet’s magnitude 5.8 blue-green speck in binoculars or a backyard telescope.

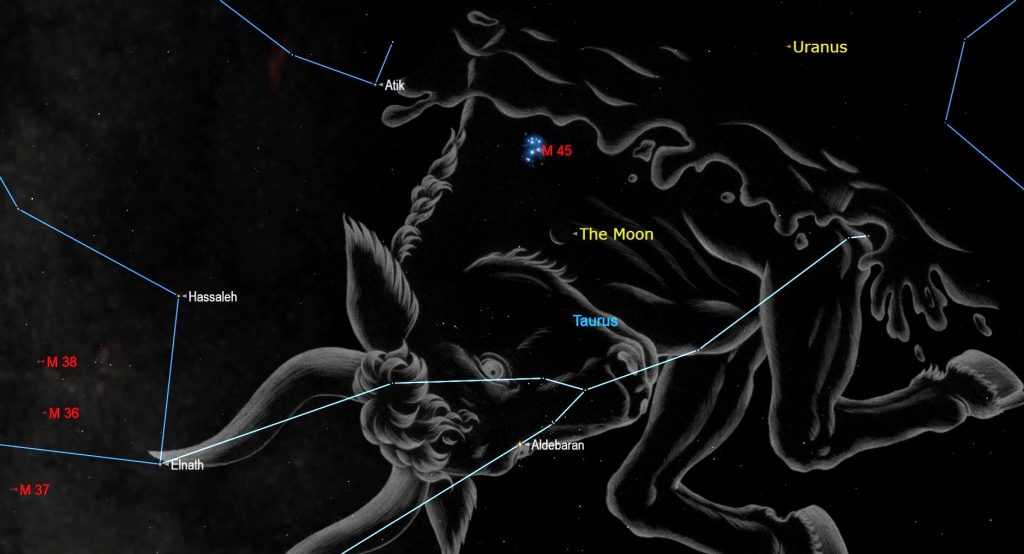

On the coming weekend, the pretty crescent moon will be travelling through Taurus (the Bull). A nice photo opportunity will arise on Saturday before sunrise, when the moon’s beautiful crescent will shine below the bright Pleiades star cluster and above the stars of the Hyades cluster. Together with the bright orange star Aldebaran, the Hyades forms the triangular face of the bull.

The Planets

What used to be a pre-dawn planet spectacle is now becoming a late-evening and overnight show! This week, Jupiter will officially enter the evening sky when it begins to rise above the eastern horizon before midnight local time, giving night-owls two bright planets to enjoy – so far. Before I highlight the bright planets, though…

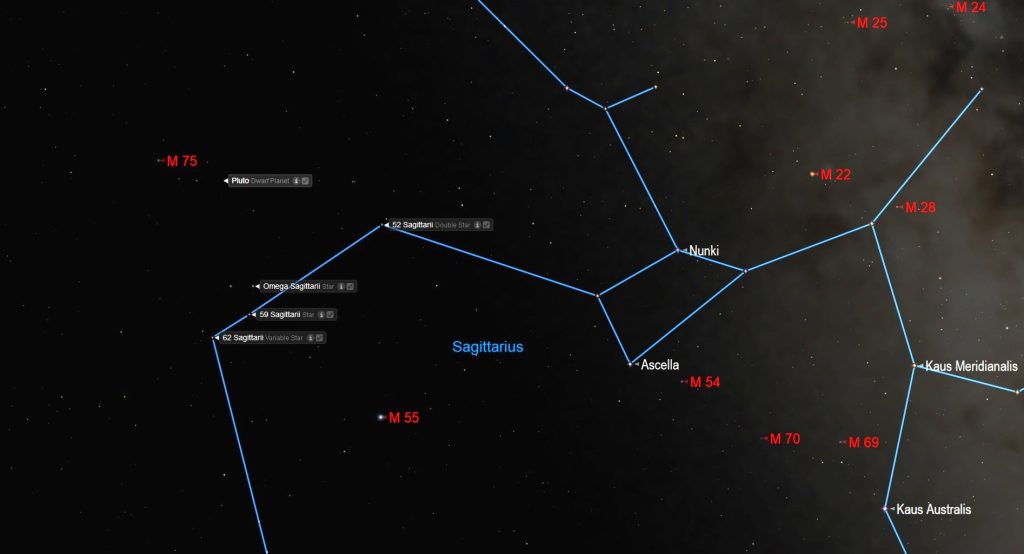

On Wednesday, July 20, the dim and distant dwarf planet designated (134340) Pluto will reach opposition for 2022. On that date, the Earth will be positioned between Pluto and the sun, minimizing our distance from that outer world and maximizing Pluto’s visibility. While at opposition, Pluto will be located 5.02 billion km, or 279 light-minutes from Earth. Unfortunately, it will shine with an extremely faint visual magnitude of +14.3 that is far too dim for visual observing through backyard telescopes.

Pluto will be low in the southern sky in evening, and will reach its highest point, due south, around 1:30 am local time. It will be located in the sky about 3 finger widths above (or 3.5 degrees to the celestial north of) the medium-bright star Omega Sagittarii, which shines well to the left (east) of Sagittarius’ Teapot-shaped asterism. Alternatively, seek out Pluto’s position two degrees to the lower right of the globular star cluster Messier 75. Even if you can’t see Pluto directly, you will know that it is there. Okay, back to your regularly scheduled Skylights…

The medium-bright, creamy yellow dot of Saturn will rise in the east-southeast at around 10 pm local time this week. Once it climbs high enough, it will shine among the modest stars of eastern Capricornus (the Sea-Goat). You can view the ringed planet until it fades from view in the lower part of the southwestern sky toward sunrise. Any size of telescope will show you Saturn’s globe extending above and below its tilted rings, and a handful of its moons arrayed around the planet. Since Saturn is now moving slowly westward in a retrograde loop that will last until late October, you can watch it shift more to the right above Capricornus’ easterly tail star Deneb Algedi for the next few weeks.

The main belt asteroid designated (4) Vesta will be positioned 1.4 fist diameters to Saturn’s lower left (or 14° to its celestial east). Its current retrograde loop will reduce its distance from Saturn in the coming weeks. In mid-July Vesta’s magnitude 6.2 speck will be observable in binoculars and small telescopes, especially between about 1:30 and 4:30 am local time (i.e., while it’s highest in a dark sky). Look for Vesta several finger widths to the upper right (or 3 degrees to the celestial northwest) of the medium-bright star Skat (aka Delta Aquarii) or two finger widths to the right of the fainter star Tau Aquarii.

During the same hours of the morning you can use a telescope to seek out the blue speck of magnitude 7.8 Neptune, which will be positioned a finger’s width to the upper right of a small star named 20 Piscium. That star sits a fist’s diameter to the right of Jupiter – on the line joining Jupiter to Saturn.

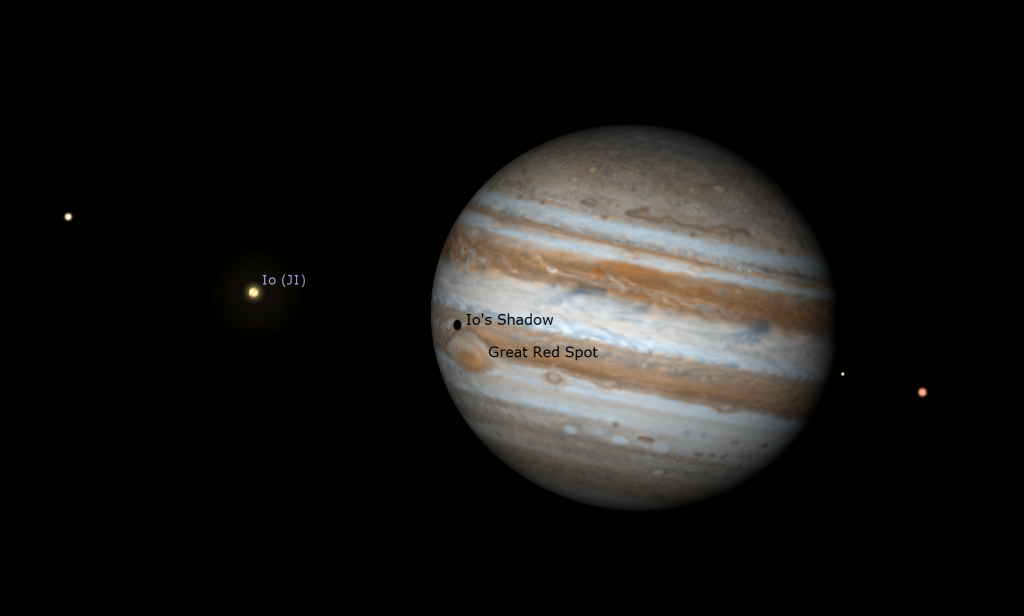

For the rest of summer and into autumn, the very bright, white dot of Jupiter will shine in the northwestern corner of Cetus (the Whale), about 4.4 fist diameters to the lower left (or 44° to the celestial northeast) of Saturn. By sunrise, Jupiter will climb to halfway up the southeastern sky. Good binoculars will show the planet’s little disk flanked by its row of four Galilean moons. They form a different arrangement each day. Planets look best in a telescope when they are higher in the sky. For Jupiter, that will be after about 1 am local time (and 30 minutes earlier than that with each passing week).

Any size of telescope will show dark bands running parallel to Jupiter’s equator. The Great Red Spot will cross Jupiter after 1 am EDT on Thursday and Saturday. Observers looking in the wee hours can see it on Monday and Wednesday morning. My long-time astronomer friend Frank Dempsey let me know that the spot looks very pale in colour nowadays – the Great Pink Spot, perhaps? Observers in western North America can see the large, black shadow of Ganymede crossing Jupiter on Monday morning, and the small shadow of Io (with the Great Red Spot) on Friday morning. The small shadow of Europa will cross on Tuesday morning.

The medium-bright, reddish dot of Mars will be obvious low in the eastern sky after it rises around 1 am local time. Mars will shine about 3 fist diameters to the lower left of Jupiter on Monday. Its distance from Jupiter will increase that by a little bit every morning. In a telescope, Mars will show a tiny, 85%-illuminated disk. The red planet will brighten and grow larger gradually as Earth’s faster orbit draws us closer to it over the coming months.

Mars’ relative quick eastward orbital motion will soon see it overtake slowpoke Uranus. This week, the magnitude 5.8 ice giant planet – easily captured in binoculars and backyard telescopes, especially between 3:30 and 4:30 am local time – will shine a fist’s diameter to the lower left of Mars. Next Sunday morning, that gap will be halved. The brightest guidepost to Uranus is the medium-bright star named Botein (or Delta Arietis). Uranus is several finger widths to its right (or 4° to the celestial southwest).

Extremely bright Venus will clear the east-northeastern treetops by 5 am local time every morning – but it won’t climb very high by sunrise – unless you live in the tropics. Venus will exhibit a waxing, nearly-round shape when viewed in a telescope or in good binoculars. The planet is creeping closer to the sun day by day. Turn all optics away from the eastern horizon before sunrise, please!

The lengthy string of planets roughly traces out the ecliptic and the plane of our solar system. Don’t forget to catch the waning moon’s passage through the planets this week.

Viewing the JWST Objects

Of the first five images released this week from the James Webb Space Telescope, two of the subjects are observable in visible wavelengths by amateur astronomers with telescopes at mid-northern latitudes on July evenings!

The Southern Ring Nebula aka NGC 6563 is a planetary nebula located just in front (or west) of the spout of Sagittarius’ Teapot-shaped asterism. The bright star at the base of the spout is Kaus Australis (Epsilon Sagittarii). The Southern Ring is positioned a generous thumb’s width to the upper right (or 2.5° to the celestial west-northwest) of that star. Although it’s a little bit low in the sky for Canadian observers, the nebula shines at magnitude 11.0, within reach of medium-sized telescopes on moonless nights. It will highest, in the southern sky, around midnight local time. It will appear as a tiny, egg-shaped orb spanning nearly 1 arc-minute in length (or 1/30 of the full moon’s diameter). If you have an eyepiece that delivers 150x or higher, it’ll show a reasonable size in the eyepiece. Once found, an Oxygen-III filter will make it easier to see. It’s certainly on my own to-view list! The JWST image is at https://www.nasa.gov/webbfirstimages#tab1-3.

The other observable JWST target is one I’ve looked several times. It’s the little group of galaxies known as Stephan’s Quintet. Discovered by Edouard M. Stephan in 1877, Stephan’s Quintet is the first compact galaxy group ever discovered. The group sits in northern Pegasus (the Flying Horse), which will be climbing the eastern sky after midnight. The spot they occupy is easily located by not quite doubling the line drawn upwards from the medium-bright star Mu Pegasi through Eta Pegasi, the knee stars in the winged horse’s forelegs. A much larger and brighter spiral galaxy, oddly-named the Deep Lick Group, is located right beside (celestial north of) the quintet.

You’ll need a 6” or larger aperture telescope and darks skies to see the Stephan’s Quintet. If you have a go-to telescope, try typing in that name, or enter one of its individual galaxies, NGC 7319, NGC 7320, NGC 7318, or NGC 7317. The quintet covers less than 4 arc-minutes of sky, so it will be difficult to see the individual members visually. Use averted vision, but no filters! Its largest member NGC 7320 is much closer to the sun than the other four – perhaps 40 million light-years, compared with 300 million light-years for the others. Its lower surface brightness makes it fainter, and its colour in images will be much bluer than its more highly red-shifted companions. Faint tidal tails, streams of stars produced by their mutual gravitational interactions and several more outlying galaxies, appear in the long-exposure images. The JWST image is at https://www.nasa.gov/webbfirstimages#tab1-2.

The other three JWST photos are of southern sky objects, namely: the Carina Nebula aka NGC 3372 in Carina (the Keel of Argo), extra-solar planet WASP-96b in Phoenix, and galaxy cluster SMACS 0723 in Volans (the Flying Fish). Of those, only the Carina Nebula is visible with unaided eyes.

Touring the Dark Southern Sky

With the moon rising after midnight and waning in phase and brightness, let’s grab bug spray and binoculars, or dust off the old telescope, and set up in a spot with a low and open southern horizon for a tour through the scorpion, the teapot, and the shield!

Once it’s getting nice and dark, face south and look for the Milky Way rising from the southern horizon. Due to haziness near the horizon, and more of Earth’s intervening atmosphere, The portion of the Milky Way higher in the sky, where it passes directly through Cygnus (the Swan), will be easier to see. By midnight local time, the great swan will be nearly overhead. The rest of the Milky Way will descend to the northeast. It thins as it passes through the “W” of Cassiopeia (the Queen) and Perseus (the Hero) because that area represents the outer edge of our galaxy’s disk.

Looking due south again – in mid-July, the distinctive constellation of Scorpius (the Scorpion) reaches its peak elevation over the southern horizon around 11 pm local time. That constellation’s brightest star is orange-tinted Antares, the “Rival of Mars”. Three white, medium-bright stars aligned in a roughly vertical line to the right (celestial west) of Antares mark the creature’s claws today – however the major stars of neighboring Libra (the Scales) used to have that role. The rest of the scorpion extends to the south, curling eastward into the Milky Way, and terminating in a bright double star named Shaula, which marks the poisonous stinger. Observers above mid-northern latitudes will struggle to see the southerly stars of the constellation. For Moana fans, the Maori of New Zealand consider those same stars to represent Maui’s fish hook pulling the Milky Way up every night!

For contrast with cool, reddish Antares, look at the two hot, white stars, both named Al Niyat, that flank the red supergiant. Magnitude 3.1 Al Niyat I (also known as Sigma Scorpii) is located 2 finger widths to the upper right (celestial northwest) of Antares. It is a B1-class star with a surface temperature of 36,200 K. Magnitude 2.8 Al Niyat II is located 2.25 degrees to the lower left (southeast) of Antares. Also known as Tau Scorpii and Paikauhale, it is a B0-class star with a surface temperature of 30,000 K. At 734 light-years from the sun, Al Niyat I is nearly twice as far away as Al Niyat II. Use binoculars to find a fuzzy patch that is sitting just a finger’s width to Antares’ right. It is a globular star cluster named Messier 4.

Late July evenings bring us one of the best asterisms in the sky, the Teapot in Sagittarius (the Archer). This informal star pattern features a flat bottom formed by the stars Ascella on the left and Kaus Australis on the right, a triangular pointed spout pointing right, marked by the star Alnasl, and a pointed lid marked by the star Kaus Borealis. The stars Nunki and Tau Sagittarii form its handle. The asterism is low in the sky, but it reaches maximum height above the southern horizon around midnight local time, when it will look as if it’s serving its hot beverage – with the steam rising as the Milky Way. By the way – the centre of our galaxy is located just 4.5 finger widths to the upper right of Alnasl!

Next, use your binoculars to explore the rich star fields and nebulae sprinkled along the Milky Way above Sagittarius. The bright star clusters known as Ptolemy’s Cluster (also designated Messier 7), the Sagittarius Star Cloud (Messier 24), and Messier 25 will appear as compact, bright, white clouds in binoculars. You can also look for the bright knots of nebulosity comprising the Lagoon Nebula (Messier 8), the Omega / Swan Nebula (Messier 17), and the Eagle Nebula (Messier 16). Higher up, you’ll discover more good clusters, including Messier 39 and Messier 29 in Cygnus, Caldwell 16 in Lacerta (the Lizard), the Wild Duck Cluster (Messier 11) and Messier 26 in Scutum (the Shield). Use your backyard telescope for a closer look at them!

Scutum (the Shield) was created by Johannes Hevelius in 1683 by stealing some of the stars from next-door Aquila (the Eagle). The small constellation (84th out of 88 by area) occupies some prime celestial real estate along the summertime Milky Way. Scutum, which reaches its highest position over the southern horizon at midnight local time in late July, has a background of rich star fields, which are overlain by some fine open star clusters, including the aforementioned Wild Duck Cluster. Use binoculars to trace out the dim stars that form the constellation and then follow up with your telescope.

Faint Comet Update

The late-rising moon will allow more views of comet C/2017 K2 (PanSTARRS) this week. The comet passed its closest point to the sun (perihelion) and to the Earth (perigee) several days ago. Over the coming weeks it will gradually fade as its climbs out of the plane of the solar system, increasingly farther from us. You can play with an online 3D model of the comet’s orbit at https://theskylive.com/3dsolarsystem?obj=c2017k2

The comet is still near its peak brightness of about magnitude 8.5. During this week, it will be travelling downwards to the right (or celestial southwestward) through central Ophiuchus (the Serpent-Bearer), roughly towards the bright star Saik. Ophiuchus’ Dalek-shaped, boxy form sits about halfway up the southern sky in late evening.

Brightest Lights of July

If you missed last week’s notes on the brightest stars on July evenings, I posted it here.

Public Astro-Themed Events

Every Monday evening, York University’s Allan I. Carswell Observatory runs an online star party – broadcasting views from four telescopes/cameras, answering viewer questions, and taking requests! Details are here. They host in-person viewing on the first clear Wednesday night each month. Other Wednesdays they stream views online via the observatory YouTube channel. Details are here.

On Monday, July 18 from 12:30 to 1:30 pm EDT, the McMaster University Alumni Association will present a free, online talk by Professor and University Scholar Laura Parker, who will discuss Hubble vs JWST. What’s the difference and why should we care? Details and the Zoom link are here.

My free, family-friendly Insider’s Guide to the Galaxy webcasts with Samantha Jewett of RASC National returns on Tuesday, August 16 at 3:30 pm EDT, when we’ll do a summer planet preview! Plus, we’ll continue with our Messier Objects observing certificate program. You can find more details and the schedule of future sessions here.

Don’t forget to take advantage of the astronomy-themed YouTube videos posted by RASC Toronto Centre and RASC Canada.

Keep looking up, and enjoy the sky when you do. I love questions and requests. Send me some!