Gemini is Generous with Meteors, a Southern Solar Eclipse, and the Great Conjunction’s Coming!

A composite image by Yin Hao of 37 frames spanning 8.5 hours of time on Dec 12/13 of the 2017 Geminids Meteor Shower. The meteors, streaks of ionized gas in Earth’s upper atmosphere, appear to be radiating from the twin stars Castor and Pollux at upper left – while Orion at lower right looks on. NASA APOD for December 15, 2017

Hello, mid-December Stargazers!

Here are your Astronomy Skylights for the week of December 13th, 2020 by Chris Vaughan. Feel free to pass this along to your friends and send me your comments, questions, and suggested topics.You can also follow me on Twitter as @astrogeoguy! Unless otherwise noted, all times are expressed in Eastern Time. To subscribe to these emails please click this MailChimp link.

I can bring my Digital Starlab portable inflatable planetarium to your school or other daytime or evening event, or teach a session online. Contact me through AstroGeo.ca, and we’ll tour the Universe, or the Earth’s interior, together!

It’s a big week for astronomy! Sunday night brings the peak of the year’s best meteor shower – under moonless skies. On Monday Morning, South America and the surrounding region will be treated to a total solar eclipse. And the Great Conjunction of Jupiter and Saturn looms closer. Read on for your Skylights!

Geminids Meteor Shower

Meteor showers occur when the Earth passes through zones of debris left in interplanetary space by periodic comets (and, in some cases, asteroids). Over many, many years, the 1-2 gram particles that range in size from sand grains to small pebbles, accumulate and spread out into an elongated “cloud” along the comet’s orbit. (A good analogy is the material tossed out of a dump truck as it rattles along. The roadway gets quite dirty if the truck drives the same route many times!) If Earth’s orbit intersects the comet’s orbit, we experience a meteor shower that repeats annually because Earth returns to the same location in space on the same date every year.

As we traverse the debris, Earth’s gravity attracts the particles, and they burn up as “shooting stars” while falling through Earth’s atmosphere. The particles enter our atmosphere at speeds between 40,000 and 256,000 km/h. As each particle’s kinetic energy ionizes the air molecules it encounters, it leaves a long trail of glowing gas that is less than a metre wide, but many kilometres long. Most trails occur in the thermosphere, the region of our atmosphere located about 80 to 120 km above the ground. Slower meteors need to reach the denser atmosphere at lower altitudes before they will form a trail. Viewed from the Earth’s surface, on a clear, dark night, we see the meteors glowing briefly as they streak across the sky – but those “shooting stars” have nothing at all to do with the distant stars of our galaxy.

Because the Earth’s orbit intersects the orbit of the source comet, we get a shower every time we return to that place in space every year. The duration and intensity of any shower depends on the breadth of the particle cloud, whether we traverse it obliquely or straight-on, and whether we pass through the core or merely skirt its edge. The quality of the shower we see depends on whether the moon is absent (yay!) or present and bright (boo!). For any given shower, the moon phase varies from one year to the next.

If you think of the Earth as a race car speeding around the sun, the meteors are like bugs hitting its windshield. The constellation that the “car” is driving towards during the shower’s active period gives the shower its name. During a shower, meteors can appear anywhere in the sky, but the members of a given shower will all appear to be traveling away from a particular location in the sky, called the radiant, that lies within the particular constellation. (This direction-of-travel rule can be broken when two showers are underway at the same time, and also by random meteors, called sporadics, which aren’t part of the main debris field, but instead are isolated particles drifting in interplanetary space.)

The Geminids Meteor Shower, always one of the most spectacular of the year, runs from December 4 to 16 annually. The Geminids will deliver a peak number of meteors after midnight on Sunday night, December 13, and then the shower will rapidly taper off during the following days. Geminids meteors are often bright, intensely coloured, and slower moving than average because they are produced by sand-sized grains dropped by an asteroid designated 3200 Phaethon.

The best time to watch for Geminids will be from full darkness on Sunday until dawn on Monday morning. At about 2 am local time, the sky directly overhead, which will be positioned near the bright star Castor in Gemini (the Twins), will be plowing into the densest part of the debris field. True Geminids will travel away from that part of the sky, but don’t just watch that location – the meteors will be shortest there, and they can appear anywhere in the sky.

This year the whole world will have moonless skies on the peak night, when up to 120 meteors per hour are possible under dark sky conditions. To be clear – that’s a maximum of two meteors per minute – and not the steady stream of them you might be seeing in photos and videos on social media or on weather channels. (Do check the weather, though – as we can’t see meteors in cloudy skies.)

To see the most meteors (during any shower), find a safe, wide-open, dark location, preferably away from the city lights, and just watch the sky with your unaided eyes for a good long while. Binoculars and telescopes are not useful for meteors – their field of view are too narrow. Try not to look at your phone’s bright screen because it’ll ruin your night vision. And keep your eyes heavenward, even while you are chatting with companions. I streamed an Insider’s Guide to the Galaxy session about meteors and meteorites. It’s on YouTube here.

Total Solar Eclipse

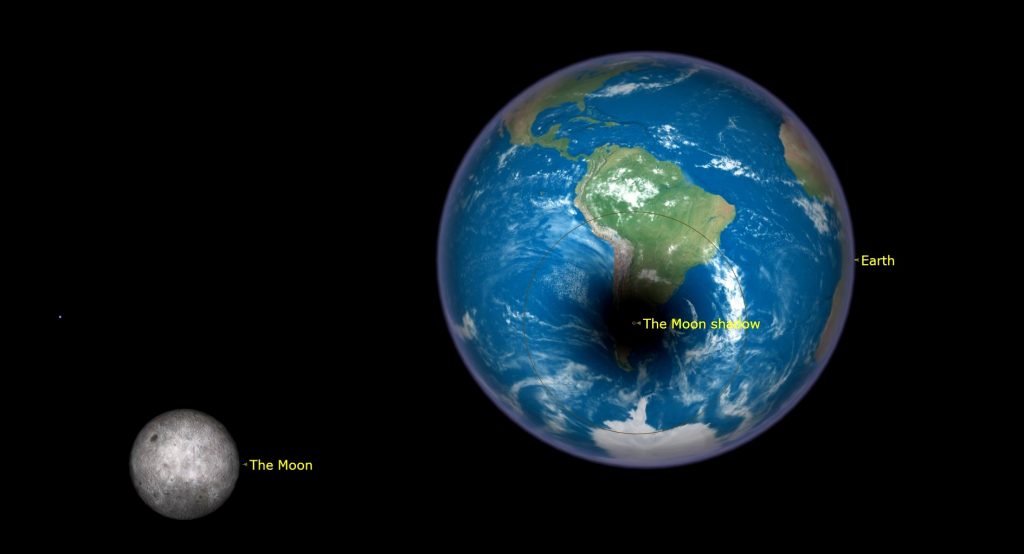

The moon will start the week off by creeping closer to the predawn sun and arriving at its new moon phase at 11:16 am EST (or 16:16 Greenwich Mean time) on Monday morning. At its new phase, the moon is travelling between Earth and the sun. Since sunlight can only reach the far side of the moon, and the moon is in the same region of the sky as the sun, the moon becomes completely hidden from view for about a day.

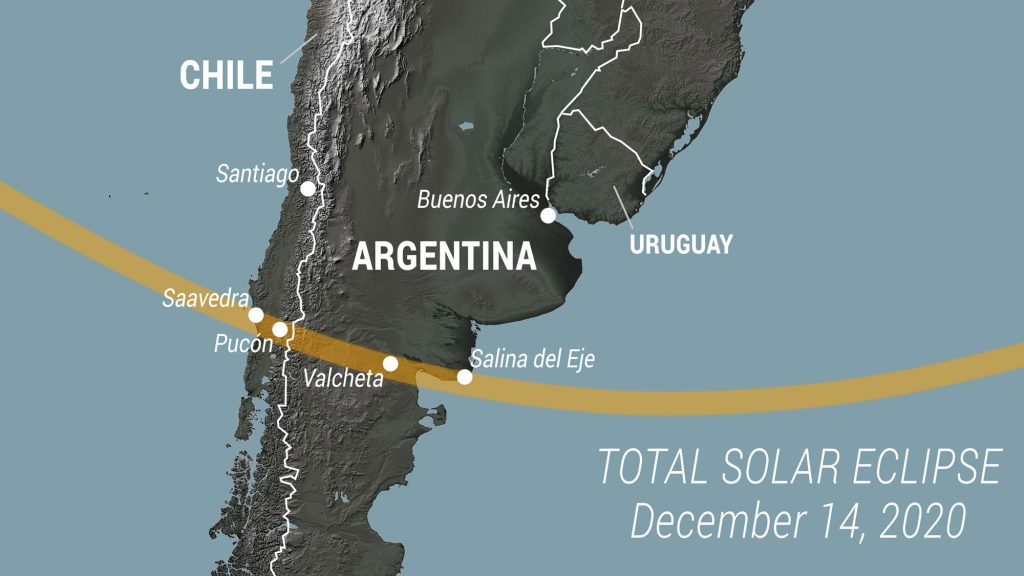

This new moon will also produce a total solar eclipse that will be visible inside a narrow track from the South Pacific Ocean, across southern South America, and ending at sunset in the South Atlantic Ocean. Areas that will receive a partial eclipse encompass about 2/3 of South America, plus much of the oceans to either side. The moon’s shadow will first contact the Earth at 14:33 GMT in the Pacific Ocean about 3900 km southeast of Hawaii. During the 97 minutes required for the moon’s umbra to reach landfall on the coast of Chile at 16:00 GMT, the path of totality will widen to 90 km. There, the sun will be at an altitude of 71°, and totality will last 2 minutes 8 seconds. Greatest eclipse will occur in Argentina at 16:13:29 GMT, with a totality of 2 minutes 10 seconds. The rest of the total eclipse will not see landfall, leaving the Earth at 17:54 GMT just 360 km west of the coast of Namibia.

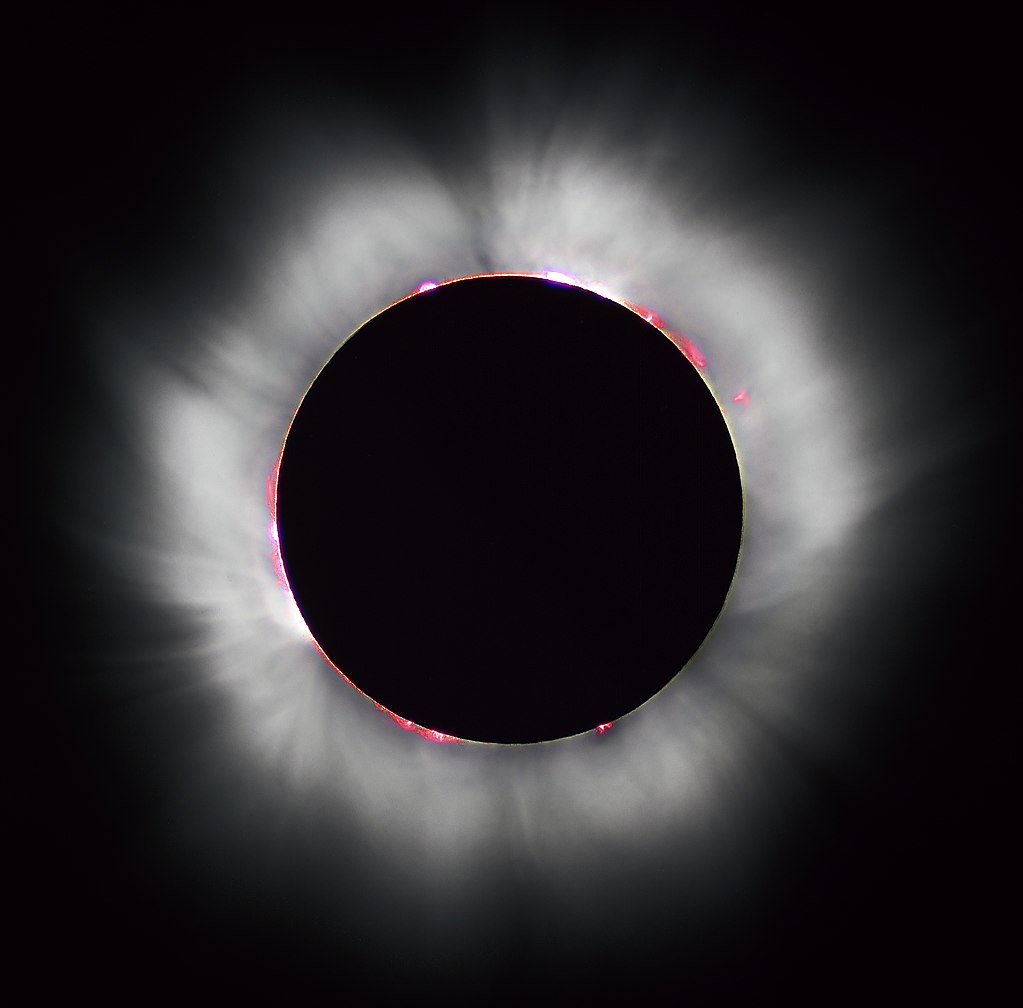

It is NEVER safe to look at a Solar Eclipse without eye protection, with one exception. Observers during the few minutes of totality may turn their gaze upon the Moon-obscured Sun and see the glorious corona and red solar prominences that rise from the Sun’s photosphere. When not totally eclipsed, part of the Sun’s disk is always exposed, and any amount of unprotected viewing is harmful to your eyes. Sunglasses are NOT enough to protect your eyes. They may make the sunlight dim enough to seem comfortable, but they do not filter out the harmful invisible ultraviolet (UV) and infrared (IR) radiation that damages eye tissue. Your retinas do not have pain receptors that will alert you to the damage you’re doing to them.

Safe methods of observing solar eclipses include special eclipse glasses (commonly inserted into astronomy magazines published prior to major eclipses), #14 or darker welder’s glass, pinhole projection setups, and special telescope filters. NEVER pass unfiltered sunlight through a telescope or binoculars. Damage to vision will be instantaneous, the equipment will likely suffer damage, and there is risk of fire, too. Solar eclipses are safe to watch when broadcast online.

NASA will be broadcasting the eclipse, with live views from Chile, beginning at 9:40 am EST (14:40 GMT). You can watch the stream through NASA’s website. The Slooh online observatory will broadcast the eclipse, beginning at 9:30 am EST (14:30 GMT) and broadcast on their Facebook page. TimeAndDate.com will also be broadcasting the eclipse on their website here beginning at 9:30 am EST (14:30 GMT).

The Moon

After Monday’s eclipse, our celestial junior sibling will return to view in the post-sunset sky on Tuesday, when you might glimpse the moon as a very slender crescent sitting just above the southwestern horizon. For the rest of this week, the moon will increase its angle from the sun – setting later and waxing fuller. That will allow observers worldwide to enjoy views of the moon during early evening.

During this week of the lunar month, the moon will look amazing in binoculars and backyard telescopes. As the moon fills with more light every night, the regions alongside the pole-to-pole boundary that separates the lit and dark hemispheres are bathed in sunlight that is arriving at a very shallow angle – brightly illuminating every peak and crater rim, and casting deep black shadows from every raised surface. Along the unlit side of the boundary, watch for isolated mountain peaks catching the sun – and for deep craters on the lit side of the moon that will exhibit dark floors until the sun rises higher. That terminator boundary line shifts east to west (or right to left for Northern Hemisphere observers) night after night, and even hour after hour – so check back regularly, if you have clear skies.

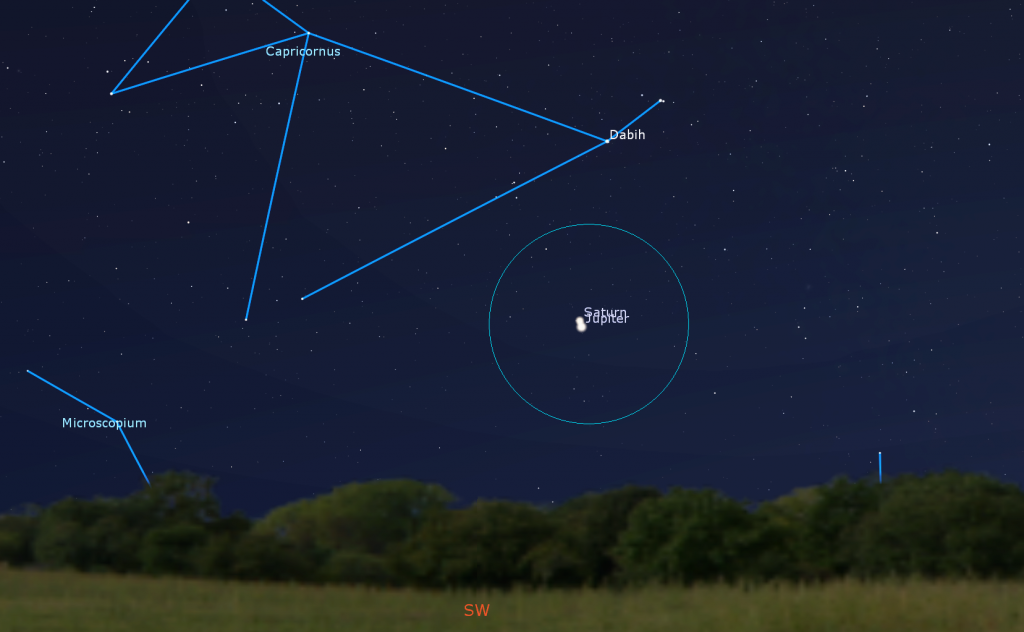

On Wednesday evening, the crescent moon will start its monthly visit with the gas giant planets. Look low in the southwestern sky at dusk for the young crescent moon sitting a slim palm’s width below the bright, close-together duo of Jupiter and Saturn. The grouping will make a wonderful photo opportunity when composed with some interesting foreground scenery. The fun will continue on Thursday when, after 24 hours, the moon’s orbital motion will have carried it a fist’s diameter to the upper left (or 9.5 degrees to the celestial southeast) of the two planets. Jupiter and Saturn will set at about 7:15 pm local time and the Moon will set 30 minutes after them.

The crescent moon will spend Thursday and Friday among the stars of Capricornus (the Sea-Goat), and then it will move into Aquarius (the Water-Bearer) for Saturday and Sunday night.

The Planets

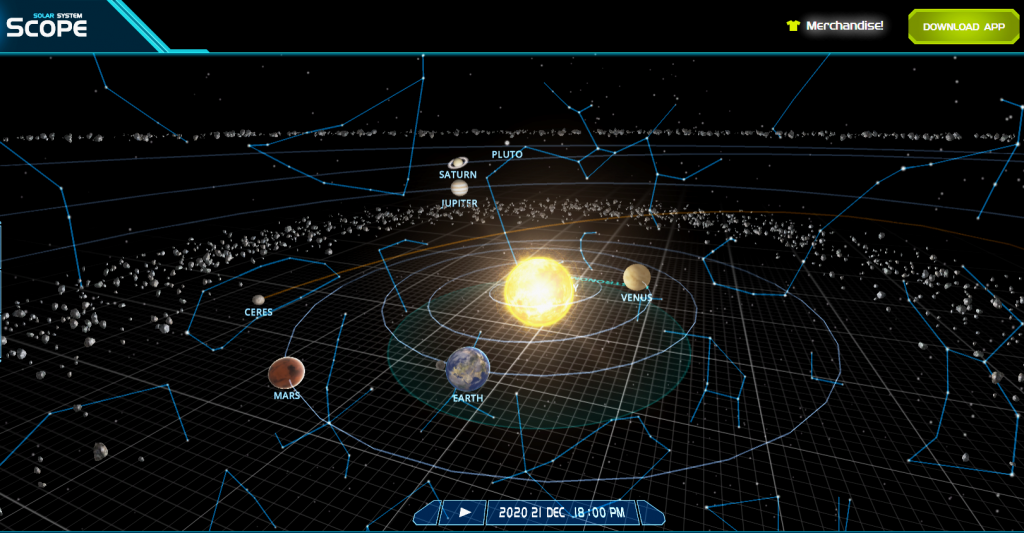

This week will take us almost to the so-called Great Conjunction on Monday, December 21, when Jupiter and Saturn will look like a single, bright ”Solstice Star” shining in the southwestern sky after sunset. You don’t need any special equipment to see the event! Just head outside after sunset and look low in the southwestern sky for bright Jupiter and one-tenth as bright Saturn sitting just to its upper left. If you can’t see them, they might be blocked by a nearby building or hill. At 6 pm local time, the planets will only be about a fist’s diameter above the horizon – and descending! With cloudy skies more frequent in December, attempt to see them every night this week! They are already close together enough to view them at the same time in most telescopes.

Here’s what’s happening. Because Jupiter is closer to the sun than Saturn is, Jupiter is moving eastward faster than Saturn. It’ll catch up and then pass Saturn on December 21. In the meantime, we can see their separation decrease every night. Tonight (Sunday), the yellowish ringed planet will sit only be a finger’s width (or 0.9 degrees) to Jupiter’s upper left. A week from now, they’ll be all but touching!

Jupiter orbits the sun once every 11.86 years, while Saturn takes 29.44 years to complete one orbit. When you crunch the numbers, those two planets meet up, on average, every 19.76 years, as viewed from Earth. (Our view of them from the moving Earth complicates the math a little.) Since each planet’s orbit is inclined a different amount from the plane of the solar system, Jupiter usually sits about a finger’s width above or below Saturn when it slips past it.

This meeting will be particularly close. On December 21, they’ll be only 6.25 arc-minutes, or 0.1 degrees apart. (The full moon’s diameter is 30 arc-minutes, or 0.5 degrees.) The last time they were this close together was July 16, 1623, when they were only 5 arc minutes apart. At that time, Galileo had been using his telescope for only a few years – but they were so close to the sun in the sky that they would not really have been visible after sunset, unless you lived near the equator. And, even then, it would have been a challenge to see them. About 800 years ago, on March 5, 1226, they were even closer together AND they were nice and high in the pre-dawn sky. Their next 6 arc-minutes separation will be an easy-to-see meet-up in the pre-dawn sky on March 15, 2080. By the way, some speculate that a close pairing like this (or an even rarer triple planet conjunction with Venus) could explain the Biblical story of the star the Magi followed.

Start enjoying views of those two planets in your binoculars and telescope now, while they are farther from the sun. That’s because every night carries them closer to the post-sunset twilight. Thankfully, the earlier sunsets are granting us a little more viewing time. You should be able to locate the planets by about 5:30 pm local time. An hour later, they will be getting quite low in the southwestern sky, and therefore shining through a much thicker blanket of Earth’s distorting atmosphere. You might even see them twinkle a little bit before they set!

Backyard telescopes of any size, or good binoculars, should let you see the four large Jupiter moons that Galileo Galilei discovered in January, 1610. Named Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto, they dance around the planet from night to night – although one or more can be hidden by Jupiter at any given time. The telescope will also be able to show you Saturn’s rings, and possibly Saturn’s largest, brightest moon, Titan!

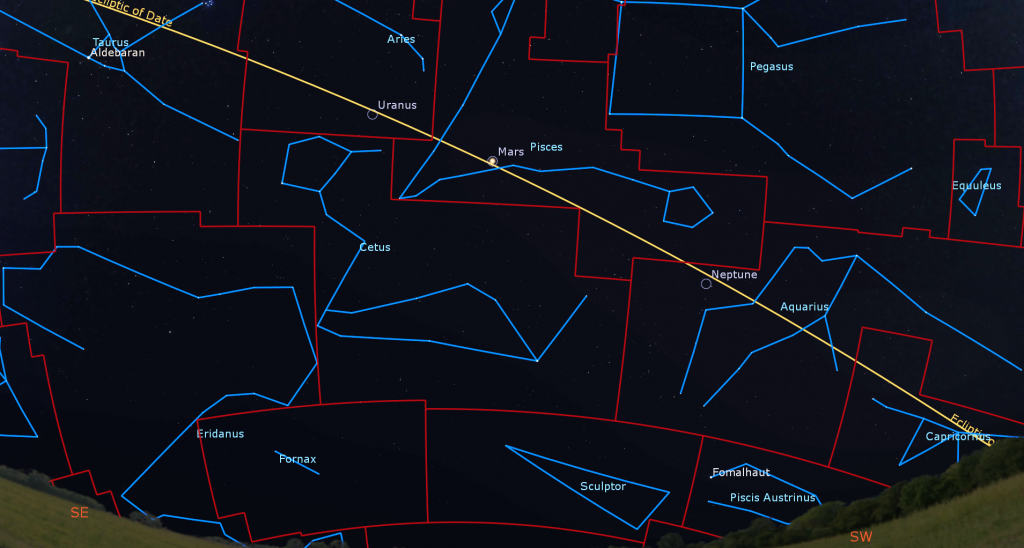

Mars is still a wonderful evening target! This week, the bright, reddish-tinted planet will already be shining in the lower part of the southeastern sky after dusk. Mars will climb to its highest point and best viewing position – more than halfway up the southern sky – shortly before 8 pm local time. Mars will set in the west during the wee hours. The planet is moving slowly eastward, and will move to inside the V-shaped stars of Pisces (the Fishes) at mid-week. Mars is rapidly fading in brightness and size from this point forward – so view it at the earliest opportunity.

Blue-green Uranus is among the stars of southern Aries (the Ram) – a fist’s diameter below and between Aries’ two brightest stars Hamal and Sheratan. For context, that region of the sky is just less than two fist diameters to the left (or 15° to the celestial east) of Mars. At magnitude 5.7, Uranus is usually within reach of backyard telescopes, binoculars, and even sharp, unaided eyes – especially with the bright moon out of the evening sky.

Deep blue Neptune is located about three fist diameters to the lower right (or 34 degrees to the celestial west) of Mars – to the left of the stars of northeastern Aquarius (the Water-Bearer). The dim, magnitude 7.86 planet is sitting less than a finger’s width to the upper left (or 0.7 degrees to the celestial east) of the medium-bright star Phi Aquarii or φ Aqr. This week, dim and distant planet will already be in the lower part of the southern sky, and descending, after dusk. So try to view it right after full darkness sets in.

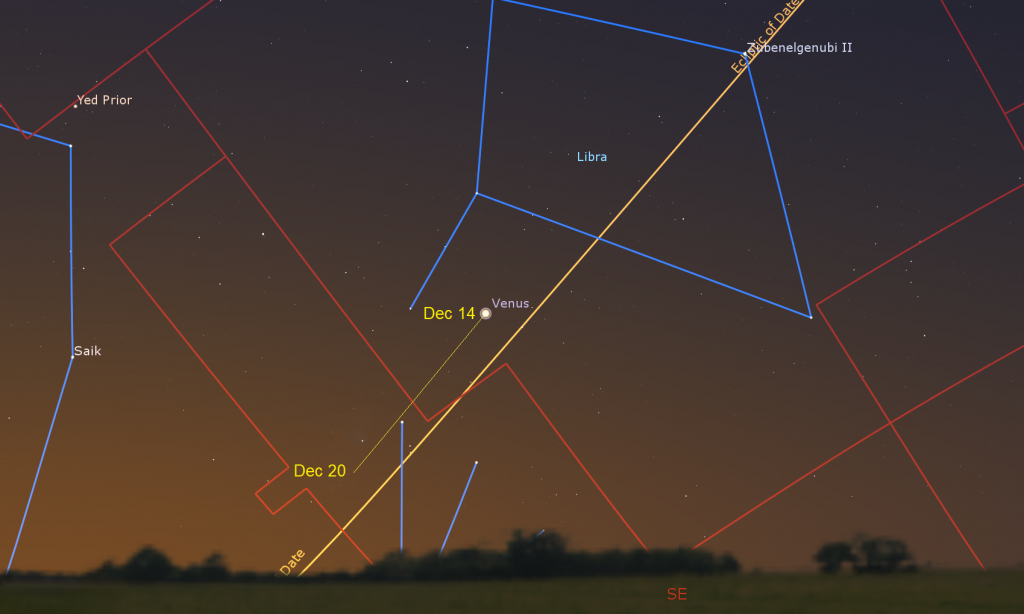

Venus has been gleaming in the eastern pre-dawn sky for some time now – but it will leave us shortly. This week Venus will rise at about 5:45 am local time, and then remain visible in the eastern sky until sunrise while it is carried higher by the rotation of the Earth. Viewed in a backyard telescope, Venus will show a slightly less than round shape. This week, the planet will be traveling down (or celestial eastward) – out of the stars of Libra (the Scales) and nearing the claw stars of Scorpius (the Scorpion). At the end of this week, Venus will start to be surrounded by the pre-dawn twilight.

Cassiopeia: Andromeda’s Story in the Stars

If you missed last week’s tour of the constellation of Cassiopeia (the Queen), I posted it with a sky chart and some photos of the best objects here.

Public Astro-Themed Events

Every Monday evening, York University’s Allan I. Carswell Observatory runs an online star party – broadcasting views from four telescopes/cameras, answering viewer questions, and taking requests! Details are here. Their in-person Wednesday night viewing has been converted to online via the observatory Youtube channel, where they offer free online viewing through their rooftop telescopes, including their new 1-metre telescope! Details are here.

On Monday evening, December 14 from 7 to 8 pm, McMaster University’s Origins Institute will livestream a free presentation entitled Understanding Planets Outside of the Solar System: From Star to Planet to Microbe. By Dr. Natalie Hinkel, a Senior Research Scientist at the Southwest Research Institute in San Antonio and a Co-Investigator for the Nexus for Exoplanet System Science (NExSS) research network at Arizona State University. More details, and the registration link, are here.

My free, family-friendly Insider’s Guide to the Galaxy webcasts with Jenna Hinds of RASC National will return on Tuesday, December 15. We’re going to talk about binoculars and winter binoculars targets! You can find more details, and the schedule of future sessions, here and here.

Our public sessions at the David Dunlap Observatory may not be running at the moment, but we are pleased to offer some virtual experiences instead in partnership with Richmond Hill. On Sunday afternoon, December 20, join me for Ask the Astronomer. We’ll talk about what’s up in the sky lately and answer your space-related questions! Depending on the weather, you may even be able to see views of the sun through a solar scope! Deadline to register for this program is Thursday December 17, 2020 at 3:00 pm. Prior to the start of the program Richmond Hill will email you information on the virtual program links and any specific information relating to your program. The registration link is here.

Keep looking up, and enjoy the sky when you do. I love questions and requests. Send me some!