Late Moon Poses Near Planets and Leaves Evening Dark for a Dolphin Dive, Autumn Brings Meteors, a Comet Shows Potential, and Planets Rule the Night!

The globular cluster NGC 6934 in Delphinus as imaged by the Hubble Space Telescope. It is also known as Caldwell 47. This image covers about 3 arc-minutes of the sky, or 1/10th of the full moon’s diameter. (Wikipedia)

Hello, Autumn Stargazers!

Here are your Astronomy Skylights for the week of September 22nd, 2024 by Chris Vaughan. Feel free to pass this along to your friends and send me your comments, questions, and suggested topics. You can also follow me on Twitter as @astrogeoguy! Unless otherwise noted, all times are expressed in Eastern Time. To subscribe to these emails please click this MailChimp link.

If you’d like me to bring my Digital Starlab portable inflatable planetarium to your school or other daytime or evening event in Simcoe, Grey, and Bruce Counties, or deliver a virtual session anywhere, contact me through AstroGeo.ca, and we’ll tour the Universe, or the Earth’s interior, together! My book with John A. Read entitled 110 Things to See With a Telescope is a guide to viewing the deep sky objects in the Messier List – for both beginners and seasoned astronomers. DM me to order a signed copy!

With autumn comes earlier sunsets. The recently full moon will spend this week rising late and lingering into morning, posing with a few planets before sunrise. The moonless evenings will be fine for exploring the little dolphin constellation Delphinus. Meanwhile, a long-awaited comet is rounding the sun this week and might brighten dramatically, a couple of meteor showers start building, and we have plenty of planets from sunset to sunrise. Read on for your Skylights!

Happy Equinox and Other Musings

Welcome to northern autumn, which arrived this morning at 8:44 am EDT, 5:44 am PDT, or 12:44 Greenwich Mean Time. I wrote in detail about the September equinox last week here.

Meteor Watch

Keep an eye out for shooting stars. As fall begins we are entering a period of increasing meteor shower activity. This week the window for two showers will commence. The Orionids will build to a peak on October 20-21, and the Southern Taurids will grow to maximum on November 4-5. In both cases the meteors will appear to radiate from the eastern sky, where those two constellations will rise late at night.

Comet Tsuchinshan Arrives

A comet named C/2023 A3 (Tsuchinshan-ATLAS) has been mentioned on social media recently as a potential bright comet to see in late September-early October. There are always a few comets around, but most of them are too faint to see without a telescope. And, even then, they only look like small, fuzzy stars.

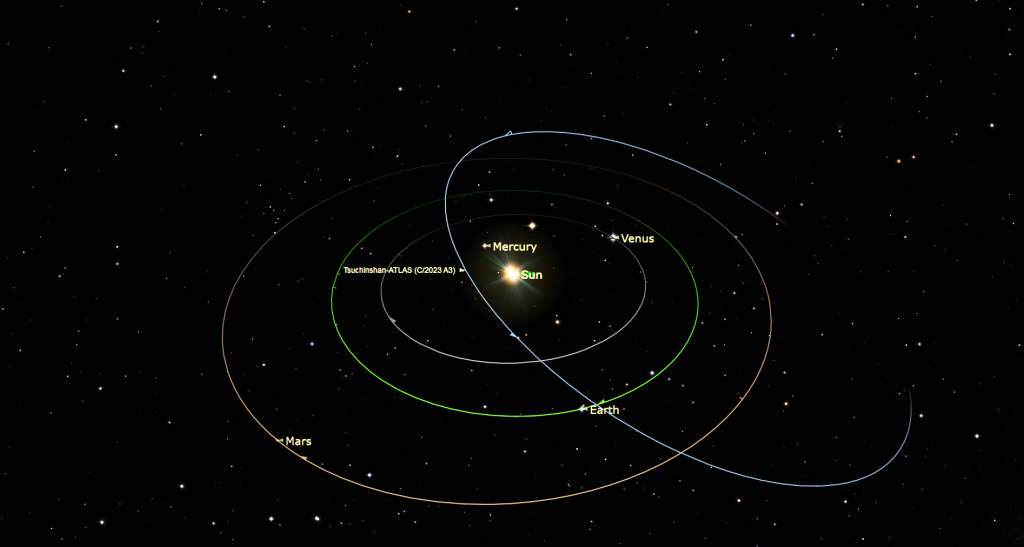

Many observatories have robotic camera systems that photograph the sky night after night and watch for “stars” that move compared to the fixed stars around them. A movement indicates that the speck is actually a comet or asteroid. We need to find as many of those as we can in order to ensure that nothing large enough to harm us will crash into the Earth without warning. Once an object is detected, it is photographed multiple times over days and weeks in order to calculate its orbit – and where it will go in the future.

Those camera systems are distributed around the globe because each Earth-based observatory can only see part of the sky. This comet was photographed on February 22, 2023 by the Asteroid Terrestrial-impact Last Alert System (or ATLAS) using the 50 cm telescope at the Sutherland Observatory in South Africa. At that time it was a teeny, 18th magnitude speck about 1 billion km away from the sun. That is closer than Saturn, but the comet itself is far smaller than any planet. Meanwhile, the object had also been photographed on January 9 by the Purple Mountain Observatory (or 紫金山天文台 Zǐjīnshān Tiānwéntái) located east of Nanjing, China. The word “Tsuchinshan” is another method of expressing “Purple Mountain” from Chinese to English. The comet’s complicated-seeming name C/2023 A3 (Tsuchinshan-ATLAS) tells us that it was the third comet discovered in the first fortnight (or two-week period) of 2023 and that both observatories have received credit for the discovery.

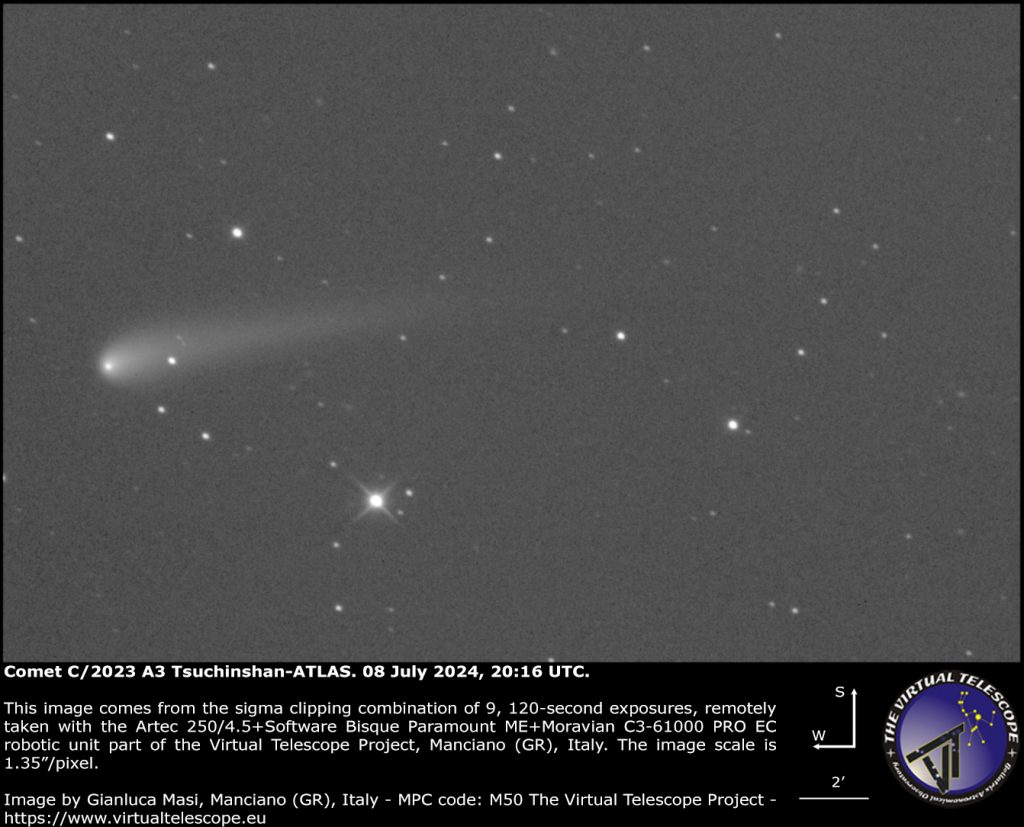

Images of the object taken in December, 2023 showed a small tail, indicating that it was a comet and not an asteroid. As it was pulled towards the sun, it steadily brightened and became observable in large backyard telescopes under dark skies. I looked at it back in May, while it was in Virgo (the Maiden). Even then, it was a tiny perfect comet!

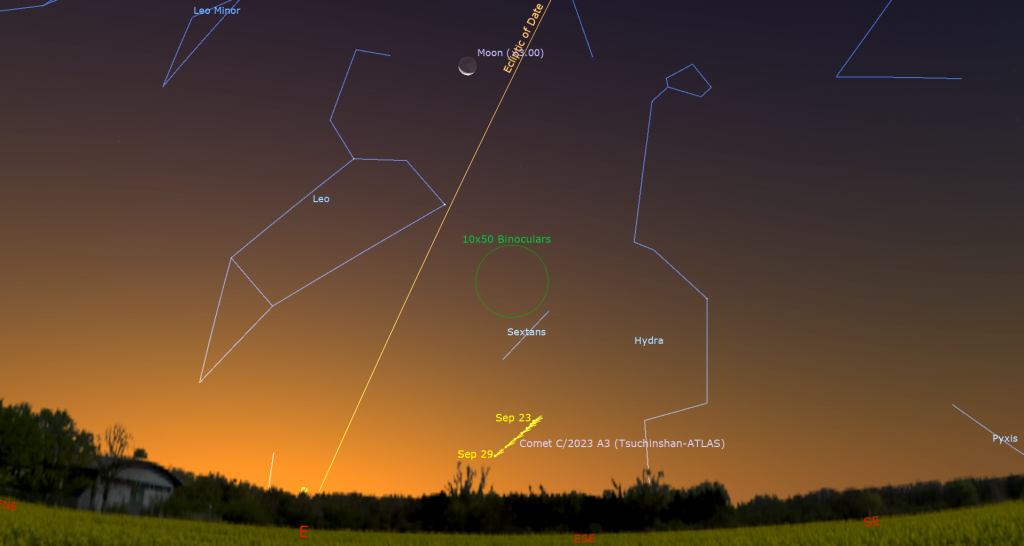

The region of the spring sky that the comet was moving in was carried into the sunset by the regular turnover of the constellations with the seasons – removing it from our view at mid-northern latitudes. At the same time, the comet’s orbit was pulling it closer to the sun. Comet Tsuchinshan-ATLAS passed solar conjunction, or the transition from evening to morning, as September began, and then became available to Southern Hemisphere observers. It’s also in the eastern sky before sunrise for those of us at mid-northern latitudes, but the section of sky it’s in is too bright for us to see it – yet!

When they aren’t sporting a tail, comets resemble a fuzzy nebula or galaxy in small telescopes. What allowed the astronomers of old, like Charles Messier, to discover comets was that they move rapidly from night to night whereas the genuine deep sky objects stayed put. This comet is moving faster now because it is approaching perihelion, its minimum distance from the sun. The increased solar warming is also encouraging it to eject more gas and dust – brightening it and boosting its tail. Those who can view it in a darker sky are reporting a magnitude value of 4.1, which is well within the range of any binoculars and telescope. Terry Lovejoy of Australia has posted some nice photos of the comet recently on FaceBook.

The comet will pass perihelion on this Friday, September 27, when it should brighten to magnitude 3.0. If it survives the maximum warming while it swings past the sun – and many comets don’t – it will then start to move closer to Earth, making it look larger and brighter for us. Over the next two weeks another phenomenon called forward scattering may make the comet look much brighter – potentially bright enough to see in daylight, if you know where to look! I’ll keep you posted.

In the meantime, you can try to see the comet from mid-northern latitudes just above the east-southeastern horizon this week after it rises at about 6 am local time. It will be positioned about 1.5 fist diameters (or 15°) to the right of where the sun will rise. Be sure to turn all of your optics away from the eastern horizon before the sun rises.

The Moon

Now that the moon has passed its full phase while opposite the sun in the sky, it will wane in phase and steadily reduce its angle from the sun. At this part of the lunar month, the moon always rises very late at night and lingers into the morning daylight for everyone around the world. That will give autumn stargazers moonless evenings to enjoy the sights of summer after sunset and the autumn stars toward midnight.

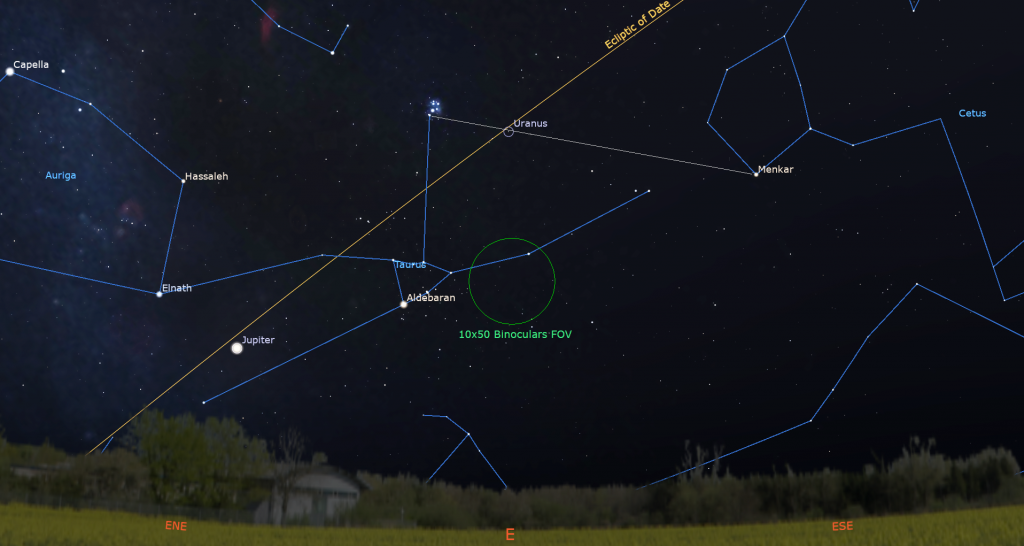

Tonight (Sunday) the gibbous moon (i.e., still more than half-illuminated) will rise at around 10 pm local time. If you are outside until midnight, or up for a glass of water in the wee hours of the night, you can see the moon shining between the bright little Pleiades star cluster and the brilliant dot of Jupiter. Aldebaran, the brightest star of Taurus (the Bull), will sparkle down to their right. Early risers on Monday can see the moon and Jupiter shining nearly overhead at dawn. The moon will sink in the western sky until noon hour.

Every night after that, the moon will rise about 45 minutes later and linger longer into the daytime afternoon while it wanes in phase. The moon will complete three quarters of its orbit around Earth, measured from the previous new moon, on Tuesday at 2:50 pm EDT, 11:50 am PDT or 18:50 Greenwich Mean Time. At the third (or last) quarter phase the moon always appears half-illuminated, on its western, sunward side. After third quarter it shows a waning crescent shape.

The moon’s eastward orbital motion across the stars will carry it through a gigantic ring of bright stars called the winter hexagon asterism, which is assembled by bright red Aldebaran in Taurus (the Bull), yellow Capella in Auriga (the Charioteer), white and yellowish Castor and Pollux in Gemini (the Twins), white Procyon in Canis Minor (the Little Dog), white Sirius in Canis Major (the Big Dog), and Rigel in Orion (the Hunter). Jupiter will spend the coming year wandering inside the hexagon. The moon will pass through it monthly.

Once the waning crescent moon has cleared the eastern treetops shortly after midnight on Wednesday morning, look for the medium-bright, reddish dot of Mars shining less than a palm’s width below it (or about 5 degrees to the celestial south). The pair will be close enough to share the view in binoculars, and will make a nice widefield photo when framed with bright Jupiter and the bright winter stars off to their upper right.

The moon will spend mid-week travelling the stars of Gemini (the Twins). Night owls and early risers on Wednesday night to Thursday morning can see the pretty sight of the waning crescent moon shining below Gemini’s brightest stars Pollux and Castor. The moon will be close enough to the lower star, warm-tinted Pollux, for them to share the field of view of binoculars and backyard telescopes. Reddish Mars will be shining to the moon’s upper right. With each passing hour, the moon will shift noticeably from right to left (or eastward) below Pollux.

On Friday morning the pretty crescent moon will be shining in the faint stars of Cancer (the Crab). The big open star cluster known as the Beehive, Praesepe, and Messier 44 will be positioned several finger widths to the moon’s lower right (or 3 degrees to the celestial south). The moon and the cluster, which is more than twice the size of the moon, will be cozy enough to share the field of binoculars, but you’ll see more of the scattered “bees” if you tuck the moon just out of sight on the upper left and look at them before the morning sky starts to brighten.

The moon will spend the coming weekend in the stars of Leo (the Lion). Its delightful crescent will be in the lower part of the eastern sky at sunrise. On next Sunday morning, keep an eye out for Leo’s brightest star Regulus sparkling just to the moon’s right.

The Planets

The dance of the planets has now delivered five of them into the evening sky worldwide – six if you don’t mind heading out after midnight or waking early! Venus, Saturn, and Jupiter are all very easy to spot. For faint Uranus and Neptune you will need binoculars or a telescope and some directions. Mars is an easy sight in the post-midnight to sunrise period. They’ll all get easier to see and available after dinner this autumn and winter – so now’s the time to get that telescope for planets! Only sun-bound Mercury will be absent over the next while.

Venus is bright enough to see even when it is surrounded by a fairly bright sky. The planet has been gradually increasing its distance from the sun every day, but the shallow angle of the ecliptic has kept the planet shining very low in the western sky. If you have an unobstructed, cloud-free view of the western horizon, you can start to look for Venus’ extremely bright, white, magnitude -3.9 dot about a palm’s width above the horizon starting a few minutes after sunset. It will be safe to use binoculars after the sun has completely disappeared. Search about two fist diameters to the left of where the sun went down. If you see something bright that is moving left or right, it’s an airplane. Venus will be higher and easier to see for folks living closer to the tropics.

Turn around and look above the eastern horizon after sunset to see the medium-bright yellowish dot of Saturn. It will climb higher while Venus drops, cross the sky all night long, and set in the west before dawn. You’ll get the clearest views of Saturn in a telescope when it’s higher in the sky between 9 pm and 4 am. The faint stars of Aquarius (the Water-Bearer) will be spread out to the right of Saturn. Binoculars will show you a bent-line trio of stars named Psi Aquarii sparkling to Saturn’s lower left. See if you can tell that the lower two are white, while the higher one is golden. Two redder stars named Phi and Chi Aquarii will appear to Saturn’s left and lower left, respectively.

We’ll be able to view Saturn on clear nights until the end of January. Saturn’s rings, which will effectively disappear when they become edge-on to Earth next March, already look like a thick line drawn through the planet’s globe. Good binoculars can hint that Saturn has rings. Any size of telescope will show the rings and Saturn’s moons! In most years, Saturn’s moons are spread all around the planet – unlike Jupiter’s Galileans moons, which are always in a line. But Earth’s perspective of the Saturn system this year and next year is making its moons line up with the rings.

Saturn’s largest and brightest moon Titan never wanders more than five times the width of Saturn’s rings from the planet. The much fainter moon named Iapetus “eye-YA-pet-us” can stray up to twelve times the ring width during its 80-day orbit of Saturn. The next brightest moons Rhea “REE-ya”, Dione “Dee-OWN-ee”, Tethys “Teth-EES”, Enceladus “En-SELL-a-dus”, and Mimas “MY-mass” all stay within one ring-width of Saturn.

During this week, Titan will move from the upper right of Saturn (or celestial west of it) tonight, pose closely above Saturn on Wednesday, and then stretch far to Saturn’s left (celestial east) on the coming weekend. (Remember that your telescope will probably flip the view around.) The rest of the moons will be tiny specks in a line beyond the rings. You may be surprised at how many you can see through your telescope if you look closely.

Earth’s perspective of the Saturn system will also cause Saturn’s moons and their small black shadows to frequently cross its disk – but you’ll need a very high quality telescope to watch those.

Last Friday night, the blue planet Neptune reached opposition, the day when it is closest approach to Earth for this year. This week’s views will be about as good. Neptune will rise at sunset and be visible all night long in a backyard telescopes – especially while it’s higher up and the sky is dark, after about 9 pm local time. During this week’s darker, moonless sky, even good binoculars can show you Neptune.

Slow-moving Neptune will spend all of this year in western Pisces (the Fishes). During evening it’s about 1.4 fist widths to the lower left (or 14° to the celestial ENE) of Saturn and a palm’s width below the circle of stars that forms Pisces’ western fish. Use binoculars to find the upright rectangle formed by the medium-bright stars 27, 29, 30, and 33 Piscium. Neptune will be the bluish, dull “star” sitting about two finger widths above (or 2° celestial north of) that box.

Uranus will spend this year as a non-twinkling, blue-green star positioned about a palm’s width to the right of the bright Pleiades star cluster in Taurus (the Bull). The slow-moving, distant planet will remain near those scattered gems until 2027! Uranus will rise around 9:15 pm local time and become high enough for viewing in binoculars or a backyard telescope after 11:30 pm. To get you in the ball-park, look for the bright star Menkar shining 2.2 fist diameters to the right of the Pleiades. Uranus will be on the line joining the bottom star of the Pleiades to Menkar.

The brilliant white dot of Jupiter will clear the treetops to the east by about midnight local time. The planet will climb to very high in the southern sky by sunrise. Jupiter will wander between the horns of Taurus (the Bull) for the next few months. It’s also about a fist’s width to the left (or 10° to the celestial ENE) of the bull’s brightest star, reddish Aldebaran. If you are look during the wee hours, or before sunrise, the reddish dot of Mars will shine to the lower left of Jupiter – like a similarly-bright reflection of Aldebaran. Mars’ relatively faster orbital motion will increase its separation from Jupiter a little more each morning.

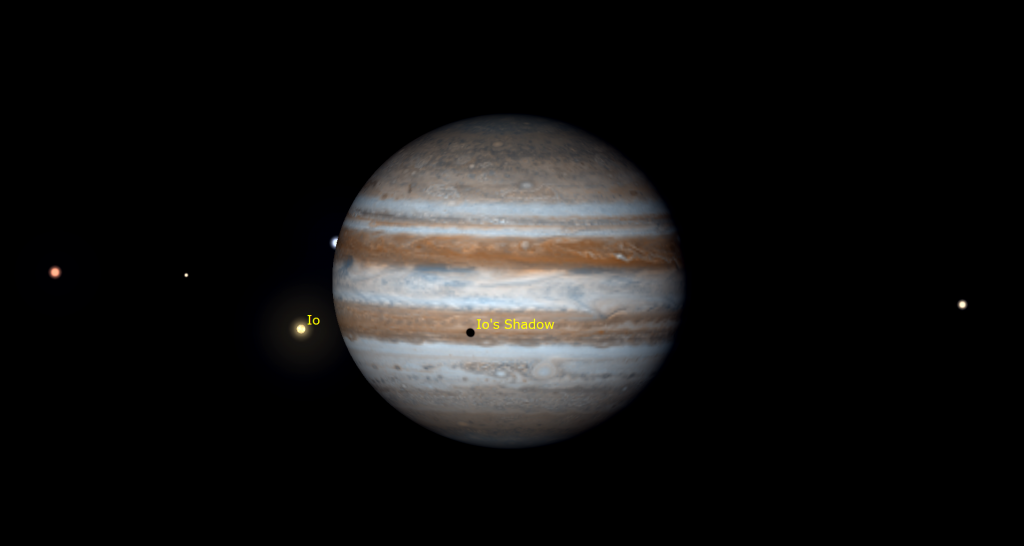

Any binoculars will show Jupiter’s four Galilean moons named Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto lined up beside the planet. Those moons complete orbits of the planet every 1.7, 3.6, 7.2, and 16.7 days, respectively. If you see fewer than four moons, then one or more of them is crossing in front of or behind Jupiter, or hiding in Jupiter’s dark shadow – or two of the moons are very close together, or one moon is eclipsing or occulting another one. On Wednesday morning in the Americas, all four moons will gather to one side of Jupiter.

Even a small, but decent quality telescope can show you Jupiter’s dark belts and light zones, which are aligned parallel to its equator. With a better grade of optics, Jupiter’s Great Red Spot, a cyclonic storm that has raged for hundreds of years, becomes visible for several hours when it crosses the planet every 2nd or 3rd night. For observers in the Americas, that GRS will cross Jupiter’s disk in the wee hours of Tuesday, Thursday, and next Sunday, and before dawn on Monday, Wednesday, and Saturday morning. If you have any coloured filters or nebula filters for your telescope, try enhancing the spot with them.

From time to time, observers with good quality telescopes can watch the black shadows of the Galilean moons travel across Jupiter’s disk. In the Americas, the large black shadow of Ganymede will cross Jupiter’s southern latitudes on Saturday, September 28 from 2:50 am to 4:40 am EDT (or 06:50 to 08:40 GMT). The smaller shadow of Io will cross Jupiter’s equator on Sunday morning, September 29 between 5 am and 7:08 am EDT (or 09:00 to 11:08 GMT).

At the end of this week, Mars begin to rise before midnight – about 90 minutes after Jupiter. It will follow the giant planet upwards to nearly overhead, but it will become hidden by the morning twilight long before brilliant Jupiter does. In a telescope, the red planet will appear as a small, rusty-coloured disk. Its position on the far side of the sun from Earth, 200 million km distant, will keep the planet looking small until later this year. This week, Mars will only be 88%-illuminated because its angle from the sun is 80°. The planet will spend this week trekking eastward near the legs of Castor in Gemini (the Twins). The pretty waning crescent moon will shine above Mars on Wednesday morning.

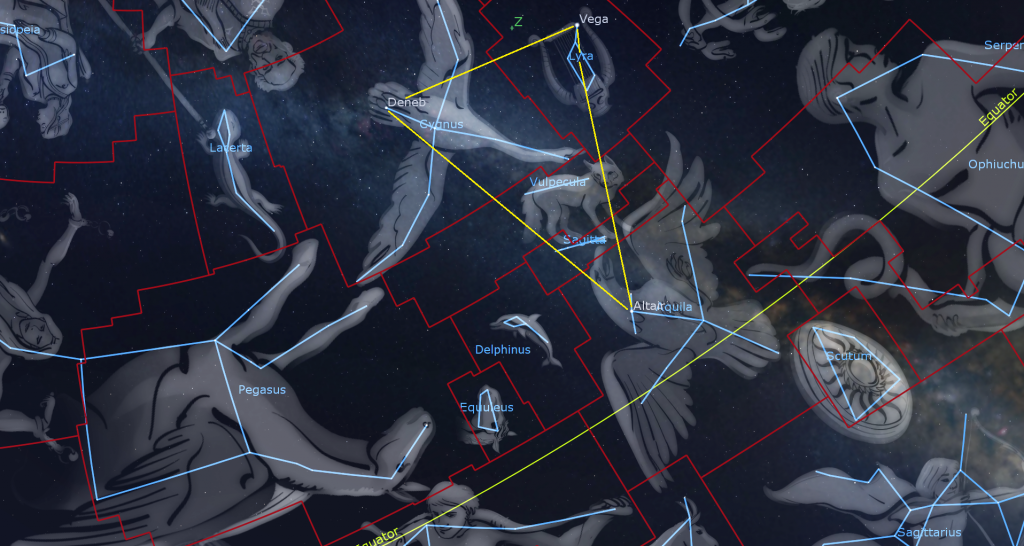

Diving into Delphinus

Sitting just to the lower left of the Summer Triangle asterism on late September evenings is a cute little constellation named Delphinus (the Dolphin). If you look southeast after dusk, the dolphin will be found swimming a little more than halfway up the sky, directly below the bright star Vega and bracketed by Deneb to its upper left and Altair to its right. The stars of the great horse Pegasus border it to the left (celestial east). Delphinus is ranked 69th in area among the 88 constellation. The even smaller constellations of Sagitta (the Arrow) and Equuleus (the Little Horse) are located above and below the dolphin, respectively. Only Crux is smaller than those two.

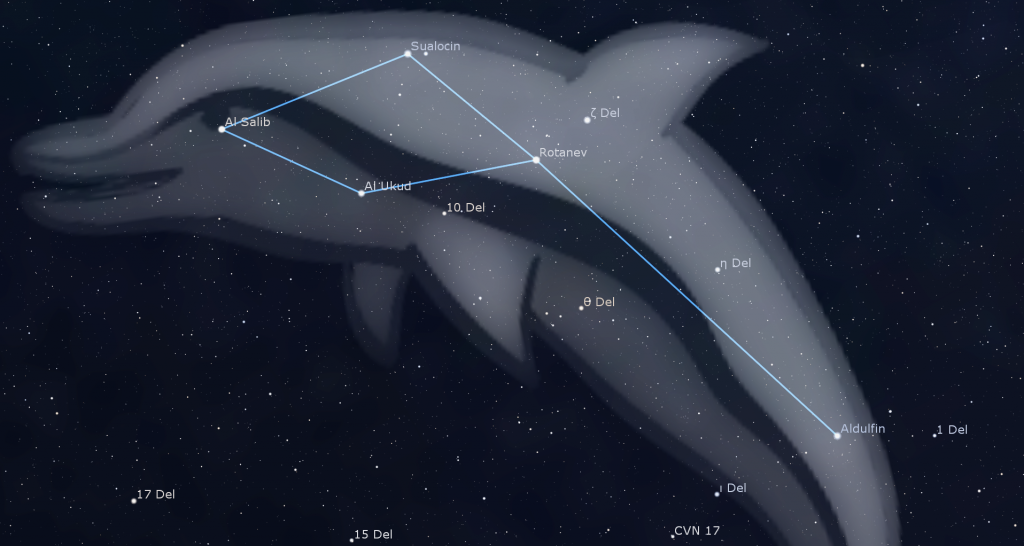

Delphinus consists of a small elongated diamond of four medium-bright stars (two finger widths across and one finger width tall) forming the head and body. The dolphin’s tail is composed of modest stars extending about three finger widths to the lower right (or celestial south) of the diamond. The creature’s five main stars can be seen with unaided eyes in a reasonably dark sky, and will all fit within most binoculars’ field of view. The little diamond of stars is also known as the asterism Job’s Coffin.

Delphinus’ location just 10° north of the celestial equator has allowed it to be enjoyed worldwide. One Greek legend tells the tale (pardon the pun) of Poseidon, god of the seas, being assisted in a matter of the heart by a friendly dolphin, and rewarding it with a place of honour in the heavens. In another story, a dolphin carried the famous 7th Century musician and poet Arion of Lesbos home to Greece after he jumped overboard to avoid being robbed and murdered by sailors on a voyage home. Apollo placed the heroic mammal in the sky next to Arion’s lyre, the constellation Lyra. Chinese astronomy sees the stars of Delphinus as a pair of gourds, and the Koreans a fruit. South American tribes saw an armadillo, while the south Pacific islanders saw the fish. To me, he could also be a Kiwi’s head!

Delphinus’ brightest two stars are bluish-white Sualocin (Alpha Delphini), where the blowhole would be, and whitish Rotanev (Beta Delphini), at the nape of the neck. Those funny names are actually the name of 19th century astronomer Nicolaus Venator spelled backwards. He participated in creation of a star catalogue, and inserted the two modest stars, for fun! Sualocin and Rotanev are 240 and 97 light-years away, respectively.

A large telescope will show that Rotanev is a very close-together double star with contrasting brightness and colour. It’s a binary system where the two stars orbit one another once every 27 years. A fainter star named Zeta Delphini that shines half a degree above Rotanev marks the dolphin’s fin. The star at the dolphin’s nose, named Al Salib or Gamma Delphini, is a somewhat wider-apart double star with one component a greenish colour. Look just below it for another easily split of stars named Struve 2725.

Use binoculars to seek out the whitish, magnitude 5.35 star named Eta Delphini sitting halfway between Rotanev and the white tail star Aldulphin, a name meaning “tail of the dolphin”. The star at the bottom corner of the diamond, marking the dolphin’s tummy, is a pulsating variable star named Al Ukud or Delta Delphini. It has an orange tint, as do the two fainter stars named 10 Del and Theta Del which are along a line between it and Aldulphin.

Delphinus lies near the Milky Way, so there are rich fields of stars to be seen throughout it. Scan around with your binoculars or telescope! The only prominent deep sky objects are two globular star clusters designated NGC 7006 and NGC 6934. They are also members of Sir Patrick Moore’s best of the sky Caldwell List, as numbers 42 and 47, respectively. Globular clusters are dense balls of stars that orbit the Milky Way galaxy, like bees around your lemonade. These two are not very bright, and need an 4” aperture telescope, or larger, to readily see them. At 135,000 light-years away, C42 is one of the most remote of our galaxy’s globulars.

Delphinus hosts several planetary nebulae, the glowing shells of gas left behind when stars similar to our sun reached the end of their lives. The Blue Flash Nebula (or NGC 6905) is located by extending a line from Al Akud to Sualocin by a palm’s width. In a good telescope it resembles a little blue egg with faint pointed ends.

Public Astronomy-Themed Events

Every Monday evening, York University’s Allan I. Carswell Observatory runs an online star party – broadcasting views from four telescopes/cameras, answering viewer questions, and taking requests! Details are here. They host in-person viewing on the first clear Wednesday night each month. Other Wednesdays they stream views online via the observatory YouTube channel. Details are here.

On Saturday, September 28 from 8:30 to 10:30 pm EDT, the in-person Astronomy Speakers Night program at the David Dunlap Observatory in Richmond Hill, Ontario will focus on observing and exploring the moon.After the presentation, participants will view interesting celestial objects through telescopes on the lawn (weather permitting). More information is here and the registration link is at ActiveRH.

On Sunday afternoon, September 29 from 12:30 to 1:30 pm EDT, head to the David Dunlap Observatory for in-person DDO Sunday Sungazing. Safely observe the sun with RASC Toronto astronomers! During the session, which is for ages 7 and up, a DDO Astronomer will answer your questions about our closest star – the sun! Registrants will be given an eclipse viewer, learn how the sun works and how it affects our home planet, view the sun through solar telescopes, weather permitting. More information is here and the registration link is at ActiveRH.

Keep your eyes on the skies! I love getting questions and requests. Send me some!