Looking at Lyrids Meteors, Seeing Spring Galaxies, and the Pretty Moon Poses with Venus!

This image taken by Ron Brecher of Guelph, Ontario on March 16, 2019 shows the bright, narrow appearance of the Whale Galaxy (or NGC 4631) at top left and the dimmer Hockey Stick or Crowbar Galaxy (or NGC 4656) at bottom right.These galaxies are about 25 and 30 million light years away from us, respectively. The area of sky shown here is about one finger’s width or 1 degree across, and should fit within the field of view of a telescope at low magnification. Note that your telescope’s optics will probably flip this view around. Ron hosts his gallery of astro-images at www.astrodoc.ca.

Hello, Galaxy Enthusiasts!

Here are your Astronomy Skylights for the week of April 19th, 2020 by Chris Vaughan. Feel free to pass this along to your friends and send me your comments, questions, and suggested topics. You can also follow me on Twitter as @astrogeoguy! Unless otherwise noted, all times are expressed in Eastern Time. To subscribe to these emails please click this MailChimp link.

I can bring my Digital Starlab portable inflatable planetarium to your school or other daytime or evening event, or we can meet-up online. Contact me through AstroGeo.ca, and we’ll tour the Universe together!

The moon will be out of sight until after it passes its new moon phase overnight on Wednesday. That will leave the skies all over the world nice and dark for enjoying the Lyrids Meteor Shower early in the week, and for viewing some spring galaxies. When the moon returns to the post-sunset western sky during the coming weekend, it will pose with bright Venus. And the three bright planets continue to dance before dawn. Here are your Skylights!

The Moon and Planets

The moon will be out of sight near the sun until Thursday or Friday after sunset, when you can glimpse its slim silvery crescent sitting low over the western horizon after sunset. The new moon phase will officially occur on Wednesday night at 10:26 pm EDT. The re-appearance of the young moon on Friday will also trigger the holy month of Ramadan.

On Saturday evening, look for pretty sight of the crescent moon sitting below bright Venus and just to the right of the bright, warm-tinted star Aldebaran in Taurus (the Bull). The Pleiades star cluster sitting a fist’s width to the lower right of the moon will add to the photogenic scene. Take a picture!

Venus will be setting at about midnight in your local time zone this week. It will finally reach its peak brightness of magnitude -4.73 next Monday. Viewed through a telescope this week, the planet will show a nice, large, and slim crescent shape. If you want to see Venus’ less-than-fully-illuminated disk, aim your telescope at the planet as soon as you can pick it out of the darkening sky. In a twilit sky, Venus’ out-of-round shape will be more apparent. And, when Venus is higher in the sky you’ll be viewing the planet more clearly – through less of Earth’s distorting atmosphere.

On Sunday night the moon will climb higher to pose for another picture beside Venus. Meanwhile, commencing at about 11:40 GMT on April 26, observers in parts of China, Southeast Asia, Philippines, and Southern Japan can see the crescent moon move in front of (or occult) the large main belt asteroid Vesta.

The southeastern pre-dawn sky continues to host three bright planets – Jupiter, Saturn, and Mars. They are strung out in a rough line measuring nearly two fist diameters in length. Jupiter leads the parade when it rises first at about 2:30 am local time. Yellowish Saturn will rise next, and then Mars will round out the trio – rising about an hour later than Jupiter. All three planets will remain visible until almost sunrise – with bright Jupiter hanging on a bit longer than the other two. During the week, Mars will continue to move away from the two gas giants.

In the Eastern time zone, Jupiter’s Great Red Spot will be crossing the planet’s disk on Tuesday morning and Sunday morning. Jupiter’s moon Io will cast its small, round, black shadow on Jupiter on Monday morning.

Lyrids Meteor Shower

The Lyrids Meteor Shower will peak before dawn on Wednesday morning, April 22 – but you can start to watch for the streaks of Lyrids meteors as soon as the sky is dark on Tuesday evening. In fact, within a couple of nights before and after the peak date, the quantity of meteors will be reduced somewhat, but still well worth looking up for. This year, the moon will be close to the sun on the peak date, leaving skies all over the world nice and dark – ideal for meteor-watching.

Meteor showers are events that re-occur annually when the Earth passes through zones of debris shed by the repeating traverses of periodic comets that have orbits that intersect Earth’s. (The analogy would be the material tossed out of a dump truck as it rattles along. The roadway gets pretty dirty if the truck drives the same route a number of times!) Over centuries, or longer, the dust-sized and sand-sized particles accumulate and spread out into a cloud along the comet’s orbit. They are more densely distributed in the core of the cloud.

When the Earth plows through one of those clouds of cemetery debris, particles are attracted by our gravity and burn up as they fall through the atmosphere at speeds on the order of 200,000 km/hr. The grains moving so fast through the air, they generate intense heat. That ionizes the air in a long, narrow tunnel surrounding the particle – producing the long glowing trails we see. The duration of a meteor shower depends on the width of the debris cloud. The shower’s intensity depends on whether we pass through the densest region, or merely skirt its edges. Since the Earth passes through the same part of the solar system on the same date every year, meteor showers repeat annually.

The source particles for the Lyrids shower is thought to be 416-year-period comet named C/1861 G1 (Thatcher), after its discoverer A. E. Thatcher. The active period for this shower is April 16 through April 25 every year. The Lyrids shower is known for producing up to 18 meteors per hour at the peak – some manifesting as bright, sputtering fireballs!

While visible anywhere in the night sky, Lyrids meteors will appear to radiate from a location in the sky (called the radiant) that is located near the bright star Vega in Lyra (the Harp), which gives this shower its name. The radiant sits partway up the eastern sky during late-April evenings – and is nearly overhead by dawn. Meteor showers are best observed in the dark skies before dawn, because that’s the time when the sky overhead is plowing directly into the oncoming debris field, like bugs splatting on a moving car’s windshield.

The highest Lyrid meteor rates this year are expected to occur on from Tuesday night into Wednesday morning April 21-22, when the Earth will be closest to the orbit of comet Thatcher and the densest part of its debris field. If you begin to watch after dark on Tuesday evening, you might catch very long meteors that are skimming the Earth’s upper atmosphere. These are fewer, but spectacular. As the night rolls on, the radiant of the meteors will rise higher in the sky, revealing more meteors because they are no longer hidden by the bulk of the Earth. The absolute best time to watch is between 4 and 5 am in your local time zone, when the radiant will be almost overhead.

For best results, try to find a safe viewing location with as much open sky as possible. You can start watching as soon as it is dark. Don’t bother to watching the radiant. Meteors near it will be heading directly towards you and will have very short trails. But do try extrapolating the streak of meteors backwards to their source, which should be near the radiant.

Bring a blanket for warmth and a chaise to avoid neck strain, plus snacks and drinks. Try to keep watching the sky even when chatting with friends or family – they’ll understand. Call out when you see one; a bit of friendly competition is fun! You’ll also see plenty of satellites gliding silently and smoothly across the sky. (Airplanes have lights that flash while satellites emit a steady or slowly pulsing glow of reflected sunlight.)

Keep your phone or tablet tucked away – its bright screen will spoil your dark adaptation. Alternatively, if you are able to, minimize the brightness or cover the screen with red film. Disabling app notifications will reduce the chances of unexpected bright light, too. And remember that binoculars and telescopes will not help you see meteors because they have fields of view that are too narrow. Good luck!

By the way, the nickname for meteors is “shooting stars” or “falling stars”. But meteors bear no physical connection to the distant stars at all. All of your favourite constellations will look the same as ever at the end of the shower!

It’s Spring Galaxy Time!

Every spring in the Northern Hemisphere, the obscuring stars, gas and dust of our own Milky Way galaxy vacate the night sky overhead, leaving a literal window of opportunity for observers to see distant galaxies. This week’s new moon will provide us with especially dark skies for hunting these faint, but majestic objects. If you don’t have clear skies, the window will re-open in mid-May.

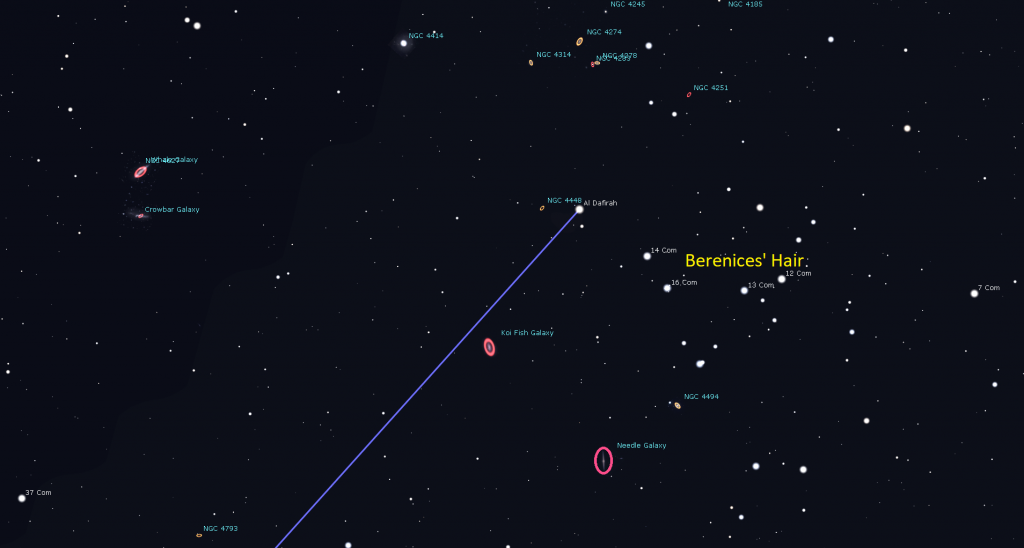

On the next clear evening this week, head outside and find a spot away from city lights and look east. About halfway up the sky, to the upper right of the bright star Arcturus, is the constellation of Coma Berenices, or “Bernice’s Hair.” This patch of sky contains the north galactic pole and therefore far fewer stars than the rest of the sky. It’s more or less overhead during late evening in April (and mid-evening in May) – perfect for viewing distant galaxies through the least amount of Earth’s distorting atmosphere. Coma Berenices and the constellations around it — Virgo (the Maiden), Leo (the Lion), Ursa Major (The Big Dipper’s home) and Canes Venatici (the Hunting Dogs) – all host a great many galaxies.

If you have a good-sized telescope (say 4” or 102 mm in aperture, or larger) and a dark location that is free of much light pollution, put your lowest power eyepiece (or lens) in it. That’s the one with the largest number printed on it. That long focal length eyepiece will show the largest possible patch of sky through the telescope – making finding galaxies easier.

Now aim your telescope at the medium-bright star named Denebola, which marks the tail of Leo (the Lion) in the southeastern sky, and focus your telescope until Denebola is a pinpoint of light. Next, without changing the focus, move your telescope to point to a spot exactly midway between Denebola and the medium-bright star Vindemiatrix in Virgo (the Maiden), which sits nearly two outstretched fist diameters to the lower left (or 17 degrees to the celestial east) of Denebola.

If your sky is dark and your eyes are dark-adapted, you should see a number of dim fuzzy patches in the eyepiece. Those are galaxies! They are members of the Virgo Cluster of Galaxies – some larger, some smaller. If you can’t be sure you’re seeing them, try lightly tapping telescope tube while you are looking. The smudges will jump around a little, allowing your brain’s wiring to see them better. Scan around to see how many you can find. (There are dozens in that patch of sky). If you mess up the focus, just start over.

Galaxies that are oriented edge-on towards Earth appear in telescopes as short, indistinct, streaks of dim light. That’s because we’re seeing the collective light from all of that galaxy’s stars squeezed into a much smaller area of sky. Try to find the star named Gamma (γ) Comae Berenices or Al Dafirah. It’s close to the limit of visibility in light polluted skies, but easier to see in rural locations. It’s the uppermost of Coma Berenices’ three main stars. A collection of slightly dimmer stars gathered just to the right of Al Difirah represents the hair of Berenice. They are see easy pick out using binoculars.

From Al Darirah, aim your telescope a slim palm’s width to the left (or 5.5 degrees to the celestial northeast). There you might glimpse the Whale Galaxy (or NGC 4631). It’s called that because, when combined with a second, smaller galaxy sitting just beside it, it resembles a whale blowing water from its spout. Another prominent galaxy called the Crowbar Galaxy, or Hockey Stick Galaxy (or NGC 4656) is positioned close enough to the whale to show up in the same field of view of your telescope. It, too, appears as a slim, fuzzy slash of light. Those two major galaxies are about 25 and 30 million light years away from us, respectively.

Returning to Al Dafirah, scan your telescope two finger widths to the lower left (or 2 degrees to the celestial east) of that star and look for the Koi Fish Galaxy (or NGC 4559). Finally, point your telescope a few fingers widths below (or 3 degrees to the celestial southeast of) Al Dafirah. There you can look for the Needle Galaxy (or NGC 4565). This galaxy is dimmer than the other two, but it sits exactly edge-on to us – making it easier to see. It is located about 57 million light-years away from our solar system!

On Space.com, you can read a column I wrote last year about classifying and viewing galaxies at https://www.space.com/skywatching. Let me know how you make out with your galaxy search!

The Insider’s Guide to the Galaxy LiveStream for Families

Insider’s Guide to the Galaxy, our weekly one-hour, live daytime astronomy broadcasts geared towards families in partnership with the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada, will resume on April 21. I hope you’ll join me and my co-host, the terrific Jenna Hinds, Youth Coordinator at RASC.

More information, the schedule, and the Zoom link to sign up are all here. If we reach Zoom’s capacity of 500 viewers, you can watch the sessions on the RASC’s YouTube channel in real time, or later on. The past sessions are all posted there, too.

Public Astro-Themed Events

Due to the COVID-19 virus, in-person public star parties and lectures have been cancelled or postponed for the moment. Here are some Internet-based astro-themed activities.

On Friday evening, April 24 at 7 pm EDT, RASC President Chris Gainor will deliver an online talk about the 30th Anniversary of the Hubble Space Telescope. For see more information and the link to register for the Zoom session, click here.

Many astronomers are running broadcasts of the views through cameras attached to their telescopes while they describe the item and take questions. A search for the terms “star party” on YouTube and FaceBook should let you find live or pre-recorded sessions.

The Canadian organization Discover the Universe is offering astronomy broadcasts for students called Astro at Home. Their website is here, and their YouTube channel is here.

On many evenings, the University of Toronto’s Dunlap Institute is delivering live broadcasts. The streams can be watched live, or later on their YouTube channel here.

The Perimeter Institute in Waterloo, Ontario has a library of videos from their past public lectures. Their Lectures on Demand page is here.

Keep looking up, and enjoy the sky when you do. I love questions and requests. Send me some!