Maximum Mercury in Evening, Morning Moon Passes Planets as Venus Kisses King Jupiter, and a Galaxy Facts Blast!

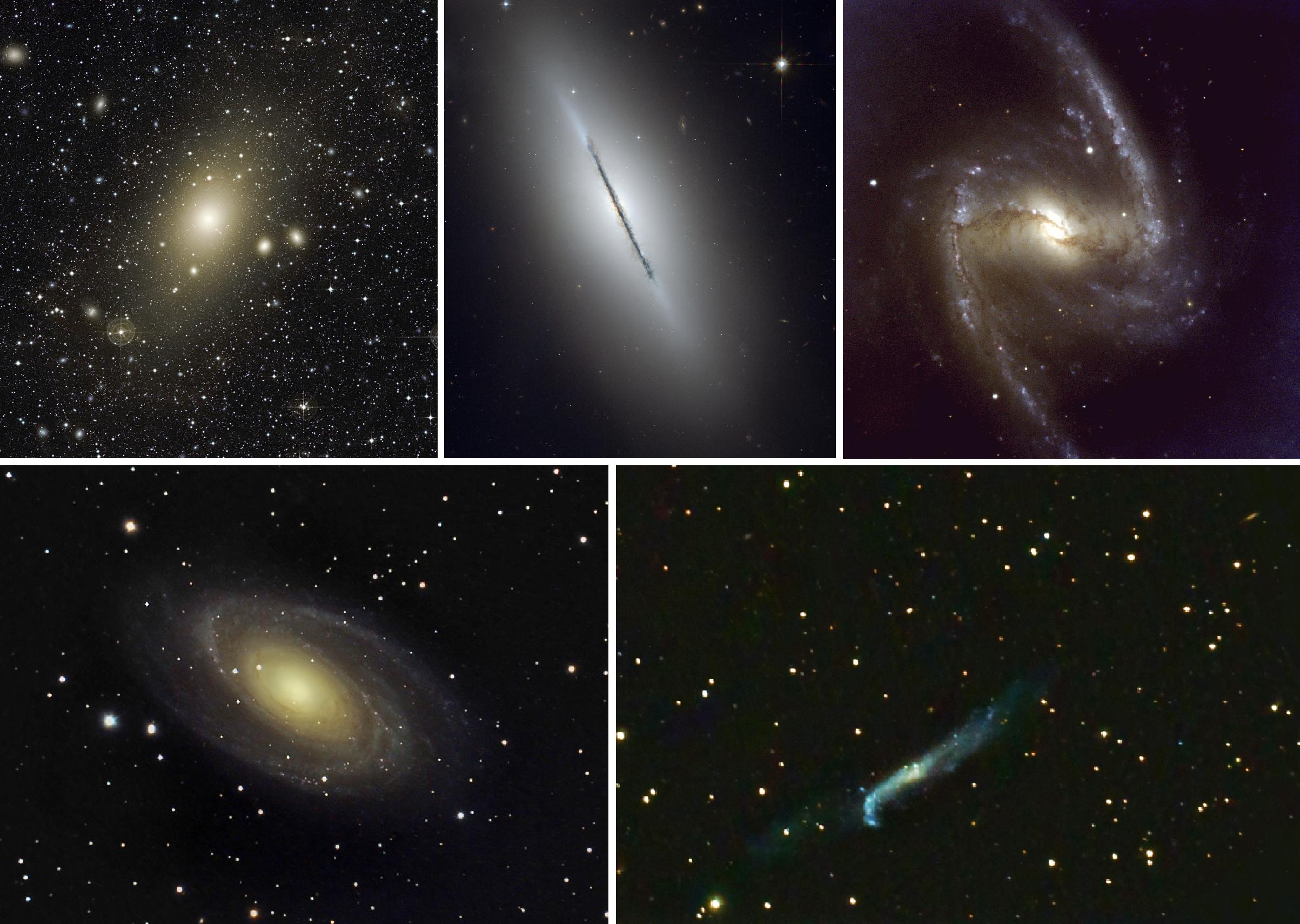

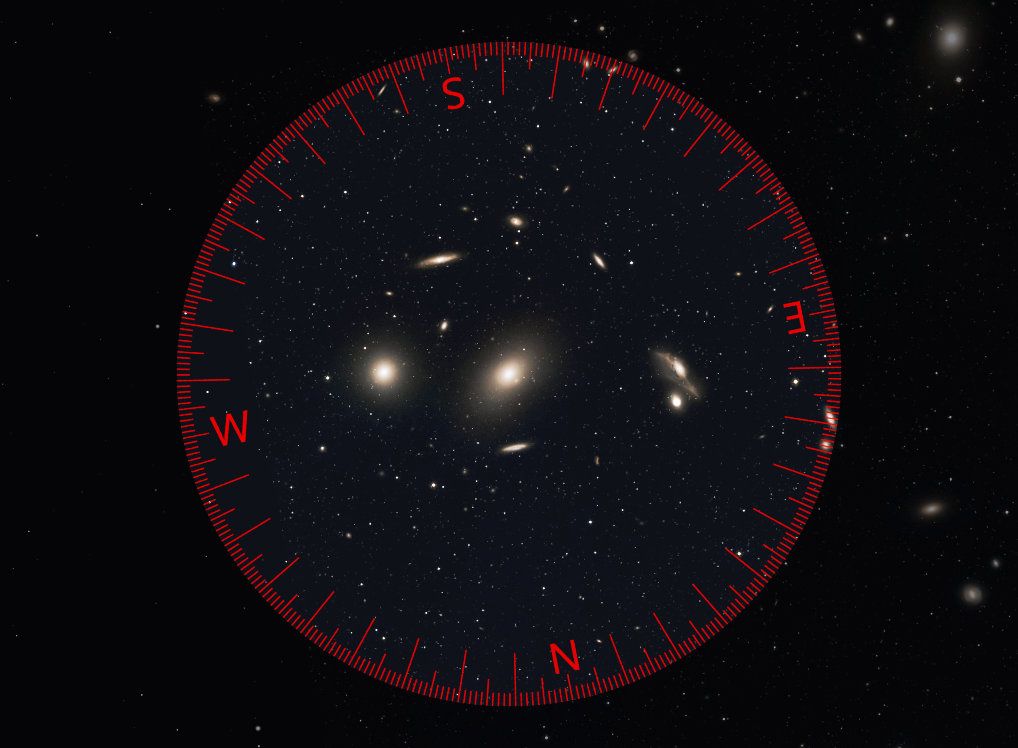

A sampling of galaxy forms. Clockwise from upper left: Messier 87 “Virgo A” (elliptical), Messier 102 “Spindle” (lenticular), NGC 1365 (barred spiral), NGC 4656 “the Crowbar” (irregular), and Messier 81 “Bode’s Nebula” (spiral). All except NGC 1365 are visible on spring evenings from mid-northern latitudes.

Hello, late-April Stargazers!

Here are your Astronomy Skylights for the week of April 24th, 2022 by Chris Vaughan. Feel free to pass this along to your friends and send me your comments, questions, and suggested topics. You can also follow me on Twitter as @astrogeoguy! Unless otherwise noted, all times are expressed in Eastern Time. To subscribe to these emails please click this MailChimp link.

If you’d like me to bring my Digital Starlab portable inflatable planetarium to your school or other daytime or evening event, or deliver a session online, contact me through AstroGeo.ca, and we’ll tour the Universe, or the Earth’s interior, together! My terrific new book with John A. Read entitled 110 Things to See With a Telescope is a guide to viewing the deep sky objects in the Messier List – for both beginners and seasoned astronomers. DM me to order a signed copy!

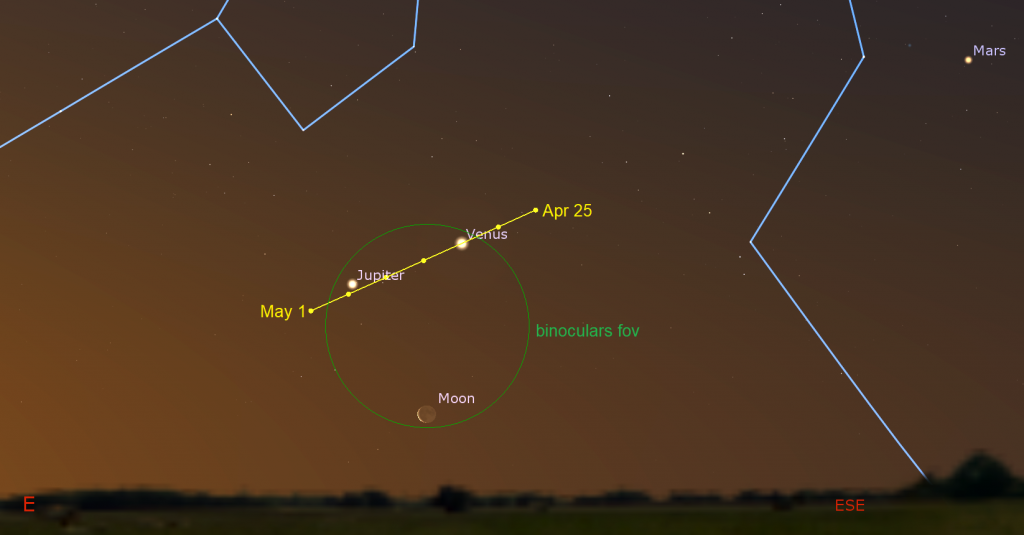

The waning crescent moon will take a trip past four bright morning planets this week. Venus will kiss Jupiter on the weekend. Meanwhile, Mercury will ascend the western sky after sunset – for maximum visibility and a close meeting with the Pleiades Cluster at week’s end. The dark, moonless skies worldwide will be ideal to see galaxies, so I share some tips. Read on for your Skylights!

The Moon

Over the course of this week of the lunar month, the moon will be shifting towards the predawn sun – so you will see it only if you are outside early; and only until about Thursday. That early morning jaunt will reward you with the picturesque sight of the old crescent moon traveling past four bright planets!

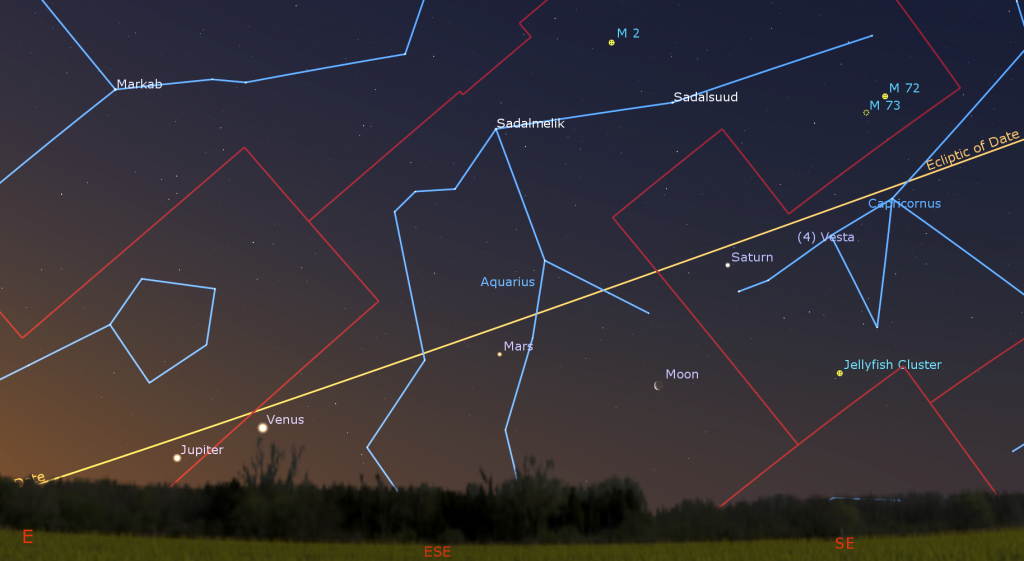

On Monday morning, the moon will shine below and between reddish Mars and yellowish Saturn – with extremely bright Venus and bright Jupiter off to their lower left (celestial east). The moon and Venus will stay visible until sunrise, at about 6:20 am local time, but fainter Mars and Saturn will fade from view by about 6 am. They’ll still show in binoculars, though. For eye safety, turn optics away from the eastern horizon before the sun rises.

Check that there is a cloud-free forecast for morning and set the alarm, especially if you want to catch the stars of Capricornus (the Sea-Goat) and Aquarius (the Water-Bearer) shining around the planets at 5 am. The moon always shifts east by about 12 degrees per day. On Tuesday, the waning moon will sit below Venus and Mars. On Wednesday, it will be parked below Jupiter and Venus. On Thursday morning, our natural satellite will drop to shine faintly about 1.3 fist diameters to the lower left of those planets. If you capture any pictures of the moon and planets, tag me or let me know!

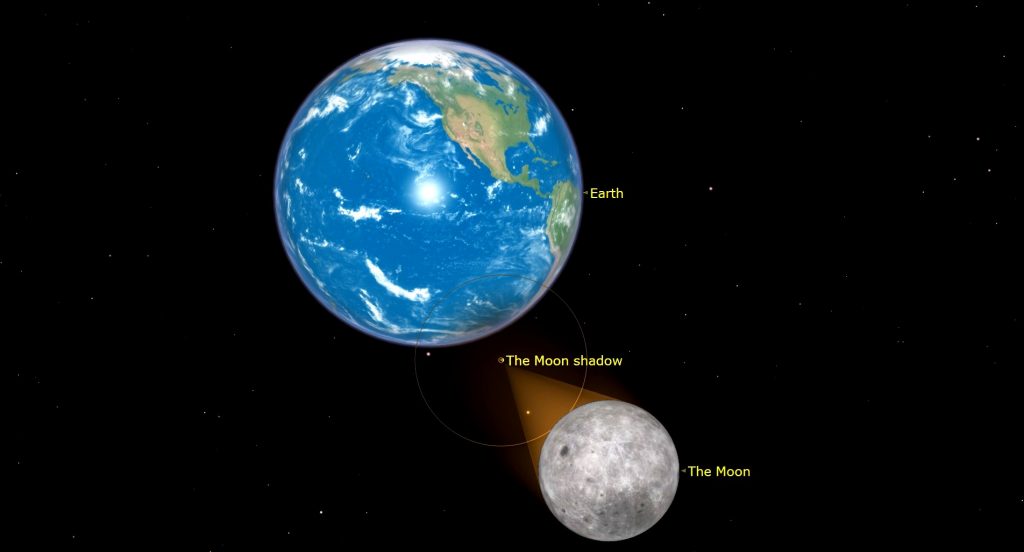

On Friday and Saturday the moon will be out of sight while it approaches and then passes the sun. The second new moon phase in this calendar month will occur at 4:28 pm EDT or 20:28 Greenwich Mean Time on Saturday, April 30. This new moon will also feature a deep partial solar eclipse that will be visible across southeastern South America, the Ellsworth Land coast of Antarctica, and the South Pacific Ocean. After the moon’s penumbral shadow first contacts Earth at 18:45 GMT, it will sweep eastward and north through Chile and Argentina until it lifts off Earth at 22:38 GMT. The instant of greatest eclipse, with the moon blocking 0.64 of the sun’s diameter, will occur at sea south of Tierra del Fuego, Chile at 20:41:26 GMT. This solar eclipse will be followed by a total lunar eclipse visible in the Americas on the night of May 15-16.

The young crescent moon will return to visibility over the western horizon after sunset next Sunday evening.

The Planets

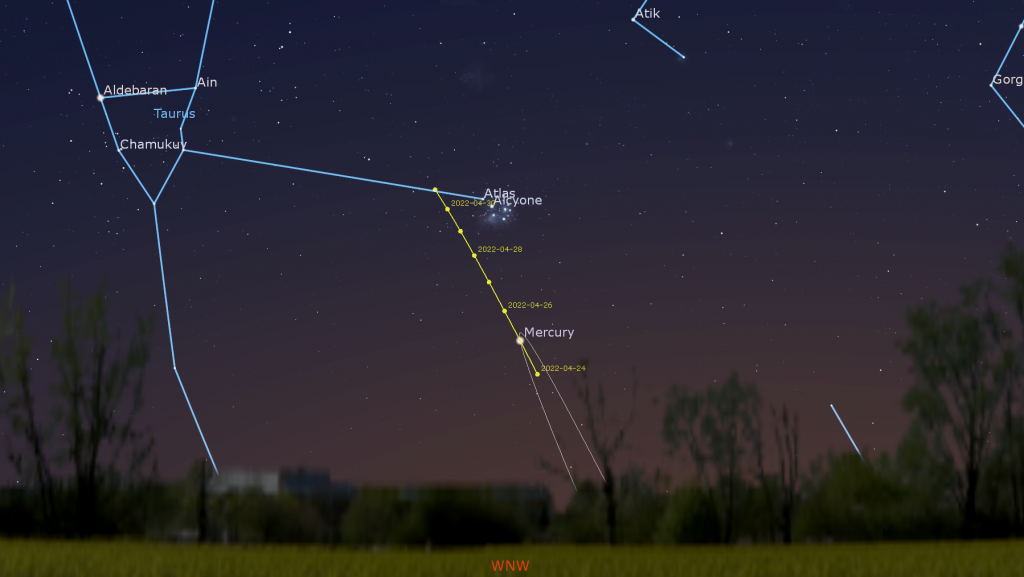

For observers located along mid-Northern latitudes, this week will offer a fantastic opportunity to see the elusive planet Mercury – a bucket-list item for many. Look for Mercury’s bright dot shining about a fist’s diameter (10 degrees) above the west-northwestern horizon as the sky begins to darken. The optimal viewing window will start shortly before 9 pm local time. The planet will climb higher on each subsequent night this week. While it’s the best evening showing for 2022 for those folks, it will be the worst appearance of Mercury for observers in the Southern Hemisphere.

On Thursday, Mercury will reach its greatest angle from the sun, and maximum visibility. Greatest eastern elongation of 21 degrees will occur on Thursday morning in the Americas, so the planet will be as good on both Wednesday and Thursday. In a telescope this week, Mercury will show a half-illuminated, waning disk and an apparent disk diameter of 7.8 arc-seconds. Always ensure that the sun has completely set before aiming binoculars or a backyard telescope towards the western horizon.

As the sky darkens towards 9:30 pm local time, Mercury will descend; but the bright Pleiades star cluster in Taurus (the Bull) will stand out above it. Mercury will climb towards the Pleiades every night, allowing the planet and the cluster to share the view in binoculars all week. On Friday, Mercury will pass less than a thumb’s width to the left (or 1.5 degrees to the celestial south) of the Pleiades; but from Thursday to Sunday, you’ll be able to see the planet and part of the cluster together in a telescope with a low power eyepiece! Take a picture!

The four bright planets that have been arrayed like beads on a string in the eastern pre-dawn sky will still be there this week – but a change will happen. Yellow-tinted Saturn will start the party when it rises after 3:30 am local time. Reddish Mars, positioned about 1.6 fist diameters to its left (celestial east), will follow about 40 minutes later. The much brighter duo of Venus and Jupiter will gleam a similar distance to Mars’ lower left from 5 am onwards. Their linear arrangement is showing you the plane of our solar system.

Head outside by about 5:30 am local time if you want to see the planets shining in a dark sky, surrounded by the stars of Capricornus (the Sea-Goat) and Aquarius (the Water-Bearer). As the sky brightens, the fainter planets Mars and Saturn will fade from sight first. As I mentioned above, the waning crescent moon will travel eastward past the planets until Thursday.

Venus will exhibit a football-shaped, half-illuminated shape in a backyard telescope. Good binoculars can reveal Venus’ shape, too. Any size of telescope will show you Saturn’s full globe, its rings, and perhaps a few of its moons. Mars will exhibit a tiny, 90%-illuminated disk. Jupiter will also get a little higher and farther from the sun with each passing day, allowing you to enjoy its dark equatorial bands, Great Red Spot, and four Galilean moons. Turn all optics away from the east before sunrise, please!

Our trip around the sun makes constellations rise about four minutes earlier every morning. Over a week, that’s half an hour – over a month, it’s two hours! That’s why the constellations change with the seasons. Meanwhile, the easterly orbital motion of all the planets causes them to move compared to those distant background stars. Distant planets like Jupiter and Saturn traverse the stars slowly – but they are still carried across the sky. Those two planets will enter our evening skies in late June and late July, respectively.

Being closer to the sun, a faster-moving planet like Mars can spend weeks in the same location in the sky while the stars roll past it – like a salmon parked in a flowing river. The inner planets Venus and Mercury are faster yet, and they can “swim” both upstream and down! You may already have noticed that Venus has been racing along the ecliptic towards the sun. In early March, it passed Mars. A month ago, it passed Saturn. (Mars and Saturn traded places over that interval.) Since then, Venus has been running towards Jupiter. They’ll kiss on the coming weekend!

During this week, and next, Venus and Jupiter will share the view in binoculars. At closest approach on Saturday, and again on the following morning, the two bright planets will appear together in the eyepiece of a backyard telescope, where six times brighter Venus will exhibit a 67%-illuminated disk, and Jupiter will be accompanied by its four Galilean moons. It’ll make a nice photo opportunity. From Sunday onwards, Venus will be the last of the four planets to rise.

It’s Spring Galaxy Time!

Last week here I wrote about the galaxies you can see most easily during the moonless weeks of April and May. This week’s evening skies will be terrific, too.

How we Describe (Classify) Galaxies

During early 1920’s at Palomar Observatory in California, astronomer Edwin Hubble was using the recently discovered Cepheid variable star period-luminosity formula to estimate the dimensions of our Milky Way galaxy. Cepheid variable stars vary in brightness over a period of time in direct proportion to their true (intrinsic) brightness. By comparing how bright the star appears with how bright it actually would be if you were a specified distance from it, astronomers could estimate how far away that star is and build up a framework for the shape and size of the galaxy.

At the time, before large telescopes were available, astronomers did not know that many of the fuzzy patches they were observing in the sky were objects outside of our galaxy; that they were completely other galaxies. They just called them “nebulas”. When Hubble found Cepheids in some of those “nebulas”, such as the one we now call the Andromeda Galaxy (Messier 31), and calculated their distances, he was astonished. Knowing how large our Milky Way galaxy is, he realized that those nebulas must be other galaxies unto themselves!

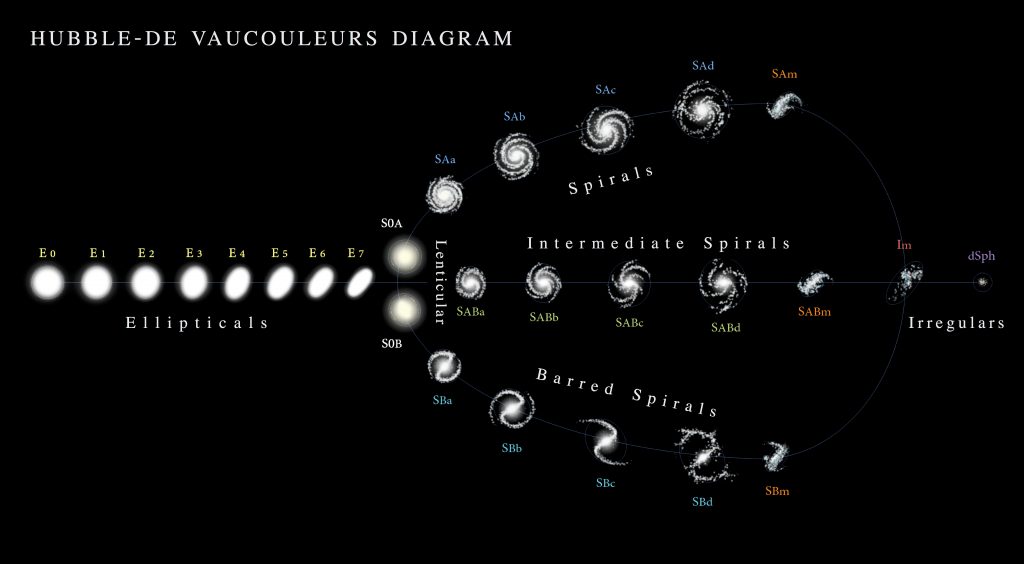

Starting in 1926, Hubble began to classify galaxies into four styles, based upon the way they look in photographs and through a telescope. He used the terms elliptical (E), lenticular (SO), spiral (S), and irregular (I). Elliptical galaxies are rather dull-looking clumps of stars ranging from round (E0) to highly stretched (E7). But they are now known to be enormous – the product of multiple galaxies merging together and losing their original structures, each elliptical hosting a supergiant black hole in the centre. Our Milky Way galaxy and the Andromeda Galaxy will merge in several billion years, probably producing a new elliptical galaxy.

Spiral galaxies have a central core with arms wrapping around it in a flattened disk. The arms can be large or small, and loosely or tightly wound. There can be many arms, or as few as two. The central core can be round or elongated. Needing a way to manage all these differences, Hubble developed the Tuning Fork scheme, where one tine held the round-core spirals (the SA type), sorted by the tightness of their arms. The other tine did the same for galaxies with elongated, or barred, cores (the SO type). He added the letters “a” to “c” to indicate how tightly wound they were.

The ellipticals formed the handle of the fork. Where the fork split, Hubble placed the lenticular galaxies. Those have a central core but no apparent spiral arms, possibly because they have “relaxed” their arms with age – more like a Frisbee than an octopus.

Starting in 1959 French astronomer Gérard de Vaucouleurs and American astronomer Allan Sandage refined Hubble’s system. They added a middle branch for intermediate spirals (SAB type), and lengthened the tines with “d” for very loosely wound, plus “m” for a single arm (i.e., barely a spiral at all). At the far end he placed the leftovers, irregular galaxies. Those are probably gravitationally distorted versions of other galaxy types.

We classify galaxies based on how they look from Earth, so there’s ambiguity, especially if they are seen edge-on. We can use spectroscopy and images taken at other wavelengths of light to peer inside galaxies and determine their form – even the edge-on ones. The galaxy’s classification codes are often displayed in programs and apps like Stellarium and SkySafari.

Tips for galaxy viewing

Here are some tips for finding and viewing galaxies.

A dark, clear, and transparent sky is the key for success with galaxies! Choose cloud-free, moonless nights (from third quarter to new moon each lunar month) and a viewing site away from artificial lights and the city light domes that wash out the night sky. Humid air can dim faint objects, too – as can forest fire smoke and dust. To maximize your eyes’ ability to see faint galaxies, avoiding looking at white light sources for at least half an hour in advance, including car headlights, flashlights, and phone and tablet screens. Dim, red light won’t spoil your dark adaptation. Cover device screens with red film. If you plan to make notes at the eyepiece, use a red headlamp or flashlight. I even cover one white notebook page with dark paper while I write on the opposite page, to reduce the glare.

You can also maximize your eyes’ sensitivity by learning to use averted vision when looking through a telescope. That’s where you focus your attention towards the edge of the field of view and let your peripheral vision pick up the faint galaxy in the middle. It works because the most sensitive light receptors in your eyes aren’t the central ones. For more visual acuity, avoid consuming alcohol before observing, try to be comfortably seated, and breathe deeply to oxygenate your eyes.

If you can’t see your target at first, tap the telescope while viewing through it. Faint objects that are in motion will draw your attention better – again using different eye receptors and brain pathways. If objects seem dimmer than expected, check that you don’t have dew or frost on your lenses and/or mirrors. At home, a hair dryer set to cool and waved across the optics from 30 cm away can clean things up. A 12v blower/fan for camping will work, too. Strapping a chemical hand warmer around the underside of your telescope can help, in a pinch.

For telescope users, always start searching for galaxies with your lowest power, longest focal length eyepiece. I like a combination that gives me a 1.5° field of view, or three times the moon’s diameter. Once you have the target, note your initial impressions, and then swap in stronger eyepieces to enlarge it. Go easy on zooming in, though. Remember that many galaxies are quite large – a substantial fraction of the moon’s diameter!

Faint objects are tough to see in small aperture finderscopes. For searching, I recommend replacing the magnifying finderscope with a Telrad or another non-magnifying (1X) finder that projects dim red bull’s-eye rings onto a window that you look through while pointing the telescope. Those are terrific because you can always see the brighter stars around the galaxy. Just place those telrad rings on or between nearby bright stars. By the way, it’s a good idea to use stars near your galaxy to focus the telescope before you look for the galaxy itself.

If you are using a star atlas or an app to find your galaxy, remember that the view in the eyepiece will probably be flipped and/or mirror-imaged. Newtonian reflector telescopes (the big cannon-type) rotate the binoculars view by 180 degrees. With them, just turn the book upside down to match the eyepiece view! Refractor telescopes and Schmidt-Cassegrain telescopes (SCT) that use a right-angle mirror to hold the eyepiece will mirror-image the regular scene. It’s helpful to know the expected field of view delivered by your searching eyepiece, too. Some people like to make FOV circles to overlay on paper atlas pages. The better astronomy apps will let you display FOV circles and to flip the display to match your telescope.

My book with John A. Read entitled 110 Things to See With a Telescope is a guide to viewing the deep sky objects in the Messier List – for both beginners and seasoned astronomers. It’s available at booksellers. I have signed copies for anyone interested.

If the galaxy you are chasing is not conveniently located near any reference stars, you can start at the best star available and then “star-hop” following recognizable star patterns. Place distinct asterisms at the edge of the FOV opposite to your target. Later, note which stars you hopped to in your observing log. Remember to account for the flipped / mirror-imaged directions.

Finally, filters will not help for visual galaxy-observing! Galaxies emit starlight, and you want as much of that as you can get!

Public Astro-Themed Events

Every Monday evening, York University’s Allan I. Carswell Observatory runs an online star party – broadcasting views from four telescopes/cameras, answering viewer questions, and taking requests! Details are here. They host in-person viewing on the first clear Wednesday night each month. Other Wednesdays they stream views online via the observatory YouTube channel. Details are here.

My free, family-friendly Insider’s Guide to the Galaxy webcasts with Samantha Jewett of RASC National returns on Tuesday, April 26 at 3:30 pm EDT, when we’ll uncover the mysteries of the constellation Leo, the Lion. Plus, we’ll continue with our Messier Objects observing certificate program and share some galaxy-viewing tips. You can find more details and the schedule of future sessions here.

Don’t forget to take advantage of the astronomy-themed YouTube videos posted by RASC Toronto Centre and RASC Canada.

Keep looking up, and enjoy the sky when you do. I love questions and requests. Send me some!