Merry Perihelion and Happy New Year, Stars Shoot Briefly, the Brightest Lights of January, and the Young Moon Poses with Planets!

This spectacular, and very well planned, image of Jupiter shining over a neighbour’s tree was captured several years ago by my talented friend Kerry-Ann Lecky Hepburn. She recently shared it on her FaceBook page as a Christmas wish for peace, love, happiness and understanding over this holiday season and heading into the new year. In that same spirit, I’m sharing it with you! May you experience many nights under sparkling stars that connect you with the Universe! Follow Kerry-Ann on FaceBook and social media for more of these treats for the eyes. https://www.facebook.com/kerryann.hepburn

Merry Perihelion, Stargazers!

Here are your Astronomy Skylights for the week of December 29th, 2024 by Chris Vaughan. Feel free to pass this along to your friends and send me your comments, questions, and suggested topics. You can also follow me on Twitter as @astrogeoguy! Unless otherwise noted, all times are expressed in Eastern Time. To subscribe to these emails please click this MailChimp link.

If you’d like me to bring my Digital Starlab portable inflatable planetarium to your school or other daytime or evening event in Simcoe, Grey, and Bruce Counties, or deliver a virtual session anywhere, contact me through AstroGeo.ca, and we’ll tour the Universe, or the Earth’s interior, together! My book with John A. Read entitled 110 Things to See With a Telescope is a guide to viewing the deep sky objects in the Messier List – for both beginners and seasoned astronomers. DM me to order a signed copy!

We look at New Year’s Day, astronomically, and perihelion, the pretty, waxing moon returning to pose with some evening planets at week’s end, and a short meteor shower. You can view all the planets in the sky this week, and I tour you through January’s brightest stars. Read on for your Skylights!

Happy New Year’s Day and Merry Perihelion!

It’s interesting that we observe January 1 as New Year’s Day around the world. Since antiquity, many cultures have based their calendars on the motions of Earth around the sun and the phases of the moon. There are lots of calendars that pin New Year’s day to the March equinox. That’s the day when the sun obviously rises due east and Mother Nature is awakening after months of slumber due to the rapidly increasing amount of daylight at that time of year. Other systems used a solstice, when the sun was obviously highest or lowest in the noonday sky. The winter solstice, the day when the hours of daylight begin to increase, albeit slowly, is certainly worthy of celebration if you live at a middle latitude and experience the long, cold nights of winter. All of those phenomena were seen to repeat once 365.2422 days. We now know that interval represents one orbit of the Earth around the sun, or a solar year.

There is nothing astronomically significant about January 1, so someone had to decide to make it a special date – and that person was Julius Caesar. Originally, the Roman calendar, established by King Romulus, commenced on the March equinox and used ten lunar months of 30 or 31 days to cover the planting, growing, harvesting seasons. Our modern months September to December reflect that pattern in their names, which key off the numerals seven through ten. The rest of the year was merely lumped into winter, and largely untracked.

At some point, the months of January and February were introduced to fill the year more formally. January was dedicated to Janus, god of gateways and beginnings. February was named after the Latin term februum, which means “purification”. The months slid around a bit, since the 29.5-day cycle of the moon produces 12.36 moons per year. Like many ancient calendars, extra, or intercalary months, were inserted every two or three years to ensure that March landed in the springtime. In 46 BCE, Julius Caesar converted the Romans’ calendar to a purely solar one of 365.25 days – perhaps influenced by Egypt’s Queen Cleopatra, who used something similar? The Romans inserted extra days on leap years to ensure that the same dates would repeat, astronomically speaking, year over year. The 0.01-day error in the Romans’ solar year led to a significant calendar drift over the subsequent centuries – enough that Pope Gregory decreed a correction to the leap year system in October, 1582. That Gregorian Calendar continues to this day.

In a way, January 1 is linked to the winter solstice – just delayed by about ten days. But wait, there’s more…

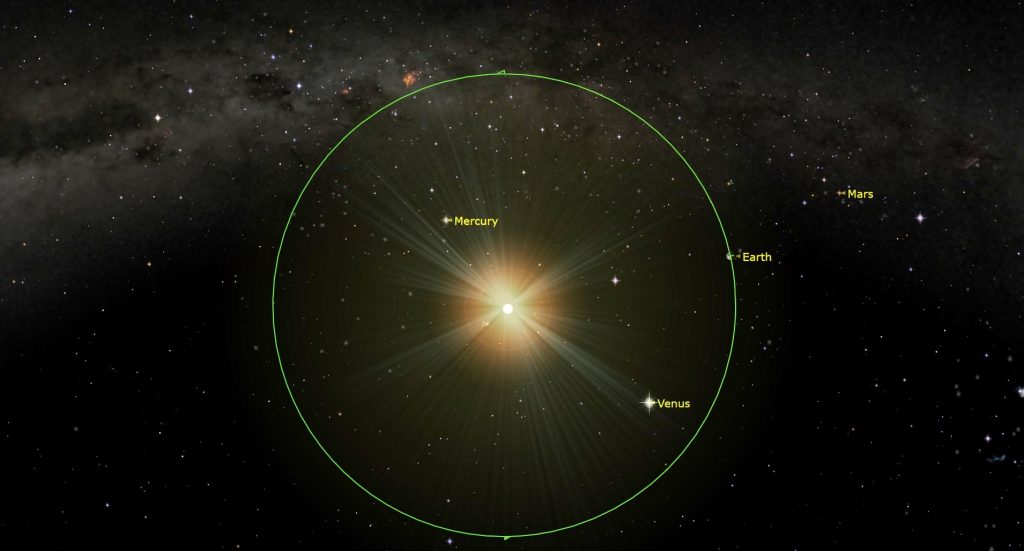

Various natural philosophers from the Greeks onward had known that the bright planets’ complicated motions through the stars could only be explained if their distance from us varied. Around 1605, Johannes Kepler developed and published his three laws of planetary motion, including that the Earth’s orbit was an ellipse that carried it closer and farther from the sun. It seems his calculations included knowing when the Earth was closer, a term he defined as perihelion. We can now calculate perihelion to a high degree of accuracy. Knowing Earth’s orbit precisely is necessary for sending spacecraft out to distant planets.

On Saturday, January 4 at 8 am EST or 5 am PST and 13:00 Greenwich Mean Time, the Earth will arrive at perihelion, its minimum distance from the sun for the year. At perihelion, Earth will be 147.101 million km from our star – or 1.67% closer than our mean distance of 1.0 Astronomical Unit (or 1.0 A.U.). Earth’s distance from the sun varies by 3.3%.

We don’t feel warmer at perihelion. As winter-chilled Northern Hemisphere dwellers will attest, daily temperatures on Earth are not controlled by our proximity to the sun, but by the number of hours of daylight we experience, which is only about 9 hours at this time of the year in the Great Lakes region. The perihelion date varies a bit year over year due to the extra quarter of a day contained in each solar year, but that error doesn’t accumulate too far because we add an extra day on those leap years I mentioned above, of which 2024 was one.

Julius Caesar didn’t set New Year’s Day on the perihelion. Perhaps if he’d known about it, he would have. Merry Perihelion everyone!

Having a Quick Meteor Shower

Named for a now-defunct, northerly constellation called Quadrans Muralis (the Mural Quadrant), which used the stars in northern Boötes (the Herdsman), the Quadrantids meteor shower occurs every year from December 26 to January 16. This particular shower’s most intense period, when 50 to 100 meteors per hour can occur, lasts for only about 6 hours surrounding the peak. You will only see that many meteors if your skies are both clear and dark during all or part of the 6-hour window. The 2025 peak will occur on Friday, January 3 at 15:00 Greenwich Mean Time. That converts to 10 am EST and 7 am PST in the Americas, favouring early risers that live on the west coast and the eastern Pacific Ocean. Moonlight will not interfere with this shower.

Meteor showers occur when Earth passes through a cloud of tiny particles in space that were deposited over time by the repeated passages of an asteroid or a periodic comet, in this case an asteroid designated 2003EH. When the particles strike our upper atmosphere at tremendous speed, they ionize the air molecules along a 1-metre-wide zone that can stretch for kilometres – producing the streaks of light we see overhead as meteors. Quadrantids commonly produce bright fireballs because its particles are stony and also burn up, adding to the spectacle. The duration of a shower depends on how quickly Earth gets through the cloud. The intensity is controlled by the particle density and whether we plough through the core or skirt its edge.

The meteors of any shower will appear to radiate from the part of the sky overhead that is pushing into the debris cloud, like bugs on a moving car’s windshield. The Quadrantids’ radiant lies beyond the tip of the Big Dipper’s handle. Meteor showers are usually worldwide events – but this one’s very northerly radiant will not climb above the horizon for observers in the Southern Hemisphere, reducing the numbers for them. Meteor-watchers near the equator will only see the half of the streaks not hidden below the Earth’s horizon.

To see the most meteors, find a safe, wide-open, dark location, preferably away from light polluted skies, and just look up with your unaided eyes. The fields of view of binoculars and telescopes are too narrow to be useful for meteors. Don’t spend too much time watching the radiant because the meteors appearing near that location will be short – but do take note of whether they can be traced backwards to the radiant. You might see some brief flashes of light near the radiant, though. Try not to look at your phone’s bright screen – it’ll ruin your night vision. Just keep your eyes heavenward – even while you are chatting with companions. Don’t forget to bundle up, and good luck!

The Bright Stars of January

We’re entering the cold (and hopefully, clear) nights of winter. Maybe it’s the crisp air, but winter’s stars seem to be the brightest stars. We also get to cheat a little because the three top stars of summer are still around in early evening. Here’s your guide to the brightest stars you can see with your unaided eyes (or binoculars) in the evening sky over the next month or so – even when the moon is around. I’ve put their brightness ranking (3rd brightest in the night sky, 7th, etc.) in brackets.

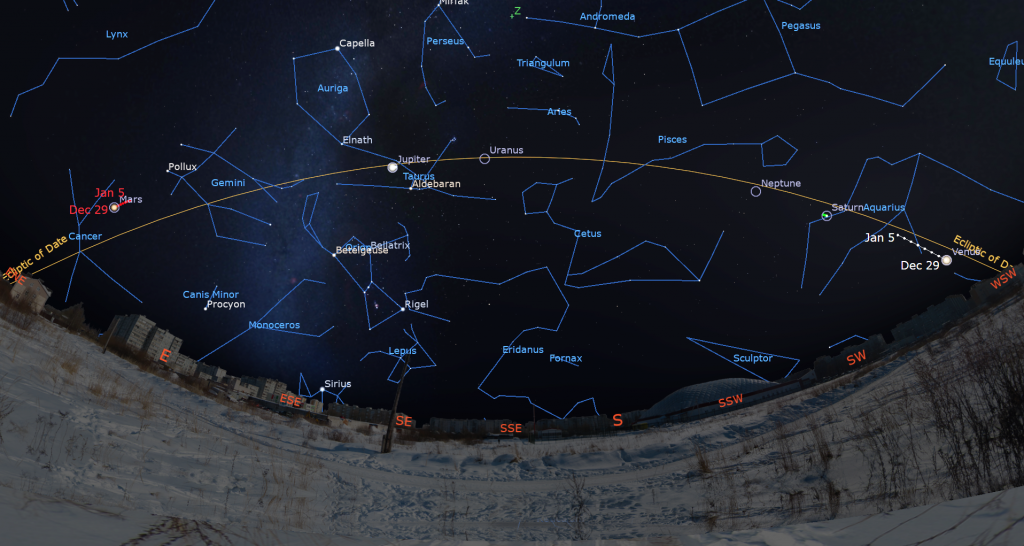

Let’s start in the western half of the sky because those stars set first. If you have an unobstructed southwestern horizon, look as soon as it’s dark for bright Fomalhaut “FOH-ma-lawt” (18th) in Piscis Austrinus (the Southern Fish) shining just above the southwestern horizon to the lower left of brilliant Venus (which outshines them all). Turning directly west, the three bright corners of the Summer Triangle asterism still shine brightly above the horizon in the early evening. The lowest of the three is Altair (12th) in Aquila (the Eagle). A bit higher, and about 3.4 outstretched fist diameters to the right of Altair, is Vega (5th) in Lyra (the Lyre). Deneb (19th) sits above and between those two. All three are hot, bluish white stars. Deneb is the tail of Cygnus (the Swan), and you should be able to see the great bird flying head-down into the west – along the Milky Way. Altair and Vega set about 8:10 and 9:45 pm local time, respectively. Deneb sets much later – at about 1:50 am local time.

Next, turn fully around and look about halfway up the eastern sky. This year, brilliant Jupiter will dominate the scene. Bright yellowish Capella (6th) is on Jupiter’s left, with orange-ish Aldebaran (14th) located about three fist widths to the right of it, and just to Jupiter’s right. Capella is the brightest star in the large oval constellation of Auriga (“Oar-EYE-gah”) (the Charioteer), while Aldebaran is the baleful red eye of Taurus (the Bull), whose triangular face is tilted sideways with his horns aimed down to the left. Both of these constellations will climb higher as the evening wears on.

The well-known constellation of Orion (the Hunter) sits directly below Aldebaran and Jupiter. His eastern shoulder is the old and bright reddish star Betelgeuse (11th), and his opposite foot is a bluish star of similar brightness named Rigel (7th). These two stars are hundreds of light-years away. Orion’s three-starred belt is a highlight of the winter sky. From east to west (lower left to upper right) they are Alnitak (30th), Alnilam (29th), and Mintaka (67th). The three stars are about evenly spaced – almost exactly 1.3° (about three moon diameters) apart. Orion’s other shoulder is marked by bluish white Bellatrix (26th), and his opposite foot is called Saiph (53rd).

To the left of Orion sits the zodiac constellation of Gemini (the Twins). Its brightest stars are yellowish Pollux (17th) and pale white Castor (23rd). Like many twins, they are a challenge to keep straight which is which. Castor, the higher star, rises first, just as “C” precedes “P” in the alphabet. Unlike identical twins, Castor is both fainter and whiter than Pollux. Gemini also hosts Alhena (43rd), the star that forms Pollux’ higher, western foot.

By about 8:30 pm local time, the night sky’s brightest star will clear the trees in the sky below Orion. Sirius (1st) is also called the Dog Star because it resides in the constellation of Canis Major (the Large Dog). A very hot, bluish-white star, it is so bright because it is our neighbour – positioned “just up the street” at only 8.6 light-years away. Sirius has a reputation for twinkling vigorously with flashes of pure colour because it sits fairly low in the sky for mid-northern latitude dwellers and they see it shining through a thicker blanket of refracting air. The big dog hosts three more bright stars, namely Adhara (22nd), Wezen (36th), and Mirzam (46th). They mark his rear leg, rump, and front paw, respectively, but you won’t see them this week until after 10 pm.

Sirius’ bright little sibling star Procyon (8th) will shine 25° (2.5 fist widths) to Sirius’ upper left, underneath Gemini in the constellation of Canis Minor (the Little Dog). Procyon, too, is relatively close to Earth. This month, the bright planet Mars will shine below Gemini and 20° (or 2 fist widths) to Procyon’s left.

By 10 pm, the bright, white star Regulus (21st), the heart of Leo (the Lion) will rise to join the party.

So, which constellation wins the award for the brightest one? Of the top 50 stars, Orion has five and Canis Major has four. Does Sirius give Canis Major the win? I’ll let you decide. Use the sky charts showing where each of these stars are and see how many of them you can learn!

The Moon

The moon will not interfere with evening stargazing worldwide until later this week. On the coming weekend, it will pose prettily near some planets and sink into the trees after mid-evening.

The moon cycles through its phases every 29.5 days, allowing a phase to repeat if it occurs early in a calendar month. For the second time in December, the moon will reach its new moon phase on Monday at 5:27 pm EST, 2:27 pm PST, and 22:27 GMT. At that time our natural satellite will be located within Sagittarius (the Archer) and 5.5 degrees south of the sun. Since sunlight is only reaching the far side of the moon at new, and the moon is in the same region of the sky as the sun, the moon will be completely hidden from view until Tuesday or Wednesday.

Your first glimpse of the young waxing moon will likely be after sunset on Wednesday. Look for its 4.5%-illuminated crescent within the relatively bright twilight over the southwestern horizon before 6 pm local time.

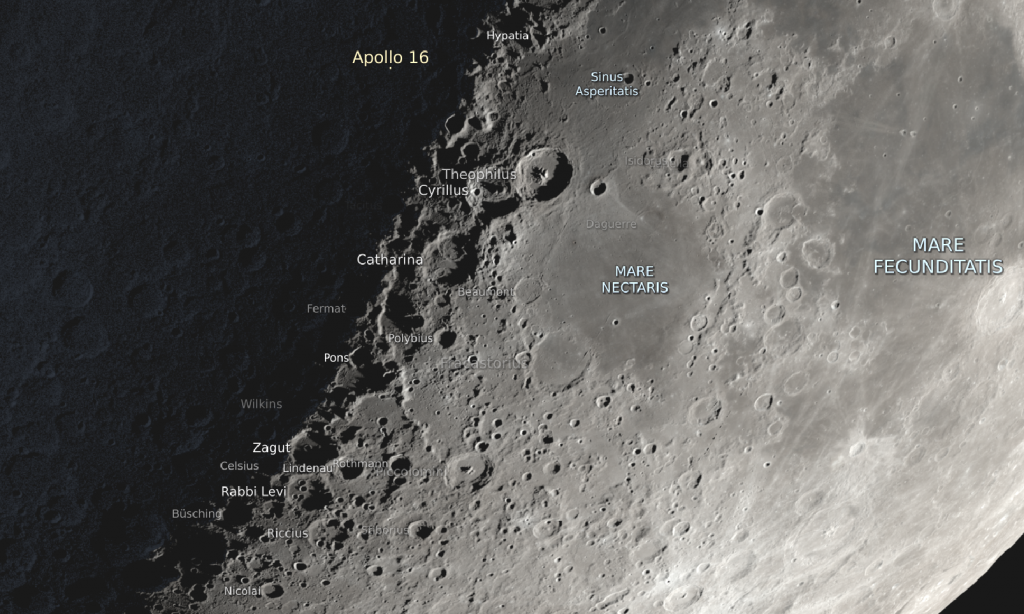

On Thursday its more substantial crescent will still be shining in the southwest as nearby Venus and the first stars emerge after dusk. Keep an eye out for Earthshine on the moon. Sometimes called the Ashen Glow or the Old Moon in the New Moon’s Arms, the phenomenon is visible within a day or two of new moon, when sunlight reflected off Earth and back toward the moon slightly brightens the unlit portion of the moon’s Earth-facing hemisphere. Binoculars or a backyard telescope will show you the dark oval of Mare Crisium within the lit crescent and lots of spectacular terrain along the curved pole-to-pole terminator boundary. The next week will deliver wonderful views of the magnified moon as it waxes.

The southwestern sky will provide a beautiful photo opportunity on Friday evening, January 3 when the pretty, waxing crescent moon will shine beside the brilliant planet Venus among the stars of Aquarius (the Water-Bearer). The moon and the planet will be close enough to share the view in binoculars from sunset until they set at about 8:30 pm local time. A backyard telescope will reveal that Venus has a half-moon shape.

In the southwestern sky after sunset on Saturday, the yellowish dot of Saturn will appear a few finger widths to the lower right (or several degrees to the celestial WSW) of the waxing crescent moon – close enough for them to share the view in binoculars. Venus will gleam to their lower right. The moon and Saturn will be visible from dusk until they set at about 10 pm local time. Hours earlier, skywatchers located in a zone extending across northwestern Africa, most of Europe, Iceland, and northeastern Greenland can safely watch the moon pass in front of (or occult) Saturn with their unaided eyes, binoculars, and backyard telescopes. Use an astronomy app to look up the event’s start and end times where you live.

The substantial crescent moon will spend Saturday and Sunday swimming through the faint stars of Pisces (the Fishes). (The zodiac constellations are famous because the sun spends time in each of them every year, and not because they have bright and prominent stars – though some do.)

Saturday evening’s terminator will also fall just to the left of a trio of large craters named Theophilus, Cyrillus, and Catharina that curve along the western edge of dark Mare Nectaris. You can tell in what order the craters were formed in by observing how sharp and fresh Theophilus’ rim appears, and by the way it has partially overprinted neighboring Cyrillus to its lower left (or lunar southwest). Under magnification, Theophilus’ terraced rim and craggy central mountain peak are evident. Cyrillus hosts a trio of degraded central peaks inside a hexagonal rim, while much older Catharina’s peak has been submerged, her edges blurred and her floor overprinted by smaller, more recent craters.

The Planets

This will be one more terrific week to see all the planets under excellent circumstances!

If you head outside on a clear evening and look towards the southwest after sunset, you’ll easily spot the brilliant planet Venus in the lower part of the sky. The planet will appear even before the sky darkens. That’s a terrific time to view it in binoculars or a telescope – while it’s higher and therefore less distorted by Earth’s atmosphere, and its half-moon shape will be more apparent. The surrounding stars of eastern Capricornus (the Sea-Goat) will appear after the sky darkens. Venus’ orbital motion will carry it away from the sun until next week. It’s also travelling toward Saturn. They’ll “kiss” in a close conjunction on January 17-18. This week, Venus will be setting at about 8:45 pm local time and Saturn will be about 1.5 fist diameters to Venus’ upper left (or 16° to its celestial east). Remember to check out the waxing crescent moon shining below Venus on Thursday and beside Venus on Friday.

The medium-bright, yellowish dot of Saturn, which is also occupying Aquarius (the Water-Bearer) this winter, will be easy to find on Venus’s upper left after the sky darkens a bit more. This week, Saturn will set at about 10 pm local time, so you’ll only have clear views of the planet in any backyard telescope until about 8 pm. The waxing moon will pose near Saturn, and occult it for observers located in northwestern Africa, most of Europe, Iceland, and northeastern Greenland, on Friday-Saturday.

Saturn’s bright, but extremely thin rings effectively disappear when they become edge-on to Earth every 15 years. Since we are less than three months away from that late March, 2025 event, the rings already appear as a thick line drawn through the planet. Any size of telescope will show the rings and some of Saturn’s larger moons. In most years, Saturn’s moons are sprinkled around the planet, unlike Jupiter’s Galileans moons, which are always in a line. But while Earth is nearly aligned with Saturn’s rings, its moons don’t stray very far from the ring plane.

Saturn’s largest and brightest moon Titan “TIE-tan” never wanders more than five times the width of Saturn’s rings from the planet. The much fainter moon named Iapetus “eye-YA-pet-us” can stray up to twelve times the ring width during its 80-day orbit of Saturn. The next brightest moons Rhea “REE-ya”, Dione “Dee-OWN-ee”, Tethys “Teth-EES”, Enceladus “En-SELL-a-dus”, and Mimas “MY-mass” all stay within one ring-width of Saturn. You may be surprised at how many of those six you can see through your telescope if you look closely when the sky is clear, dark, and calm.

During early evening this week, Titan will start from a position just to Saturn’s right (or celestial west) tonight (Sunday). It will switch to the planet’s left on Monday and then increase its separation until Thursday before swinging halfway back toward the planet next Sunday. (Remember that your telescope will probably flip the view around.) The rest of the moons will be tiny specks in a line near the rings. Earth’s perspective of the Saturn system will also cause Saturn’s moons and their small black shadows to frequently cross its disk – but you’ll need a very high quality telescope to watch those.

The distant and dim, blue planet Neptune is about an hour behind Saturn on the ecliptic. That places Neptune 1.3 fist widths to Saturn’s upper left (or celestial ENE) and a palm’s width to the lower left of the circle of faint stars that forms Pisces’ western fish. Neptune will be visible in a backyard telescope this week and next while the moon is absent. Use binoculars to find the upright, tilted rectangle formed by the medium-bright stars 27, 29, 30, and 33 Piscium. Neptune will be the bluish, dull “star” sitting about two finger widths to the upper right (or 2° to the celestial north) of that box. Neptune will look best in a telescope when it will be higher in the sky, before 9 pm.

Uranus and Jupiter are climbing the southeastern sky after dusk and highest due south in late evening, so you have plenty of time to view them this week. This month, the distant ice giant planet Uranus will be observable any time after dusk. It is located in the eastern early evening sky about a palm’s width to the right (or celestial southwest) of the bright little Pleiades star cluster in Taurus (the Bull). If you use your binoculars to find the medium-bright stars named Botein and Epsilon Arietis, Uranus will be the dull-looking blue-green “star” located several finger widths below (or southeast of) them. To get you in the vicinity of Uranus, look for the bright star Menkar shining 2.2 fist diameters off to the right of the Pleiades and down a little. Uranus will be a quarter of the way along the line joining the bottom star of the Pleiades to Menkar. In late evening, Uranus will be below the Pleiades in the southwestern sky.

The giant, white planet Jupiter will grab your attention in the lower part of the eastern sky after dusk – around the same time that Venus appears in the southwest. From now until early February, Jupiter will be creeping west towards the stars that form the triangular face of Taurus (the Bull) and Taurus’ brightest star, reddish Aldebaran, which marks the eye of the beast at the lower corner of the triangle. This week, Jupiter and Aldebaran will be less than a palm’s width apart. The winter constellations will rise below Jupiter every evening. By the time the clock strikes midnight, those constellations will have rotated to the planet’s left.

Viewed in any size of telescope, Jupiter will display a substantial disk striped with brown dark belts and creamy light zones, both aligned parallel to its equator. With a better grade of optics, Jupiter’s Great Red Spot, a cyclonic storm that has raged for hundreds of years, becomes visible for several hours when it crosses the planet every 2nd or 3rd night. For observers in the Americas, that GRS will cross Jupiter’s disk during early evening on Sunday, Wednesday, Friday, and next Sunday, and also towards midnight Eastern time on Thursday and Saturday night. If you have any coloured filters or nebula filters for your telescope, try enhancing the spot with them.

Any size of binoculars will show you Jupiter’s four Galilean moons named Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto lined up beside the planet. Those moons complete orbits of the planet every 1.7, 3.6, 7.2, and 16.7 days, respectively. If you see fewer than four moons, then one or more of them is crossing in front of or behind Jupiter, or hiding in Jupiter’s dark shadow – or two of the moons are very close together, or one moon is eclipsing or occulting another one. All four moons will gather to one side tonight (Sunday) and next Sunday.

From time to time, observers with good quality telescopes can watch the black shadows of the Galilean moons travel across Jupiter’s disk. In the Americas Europa and its little shadow will cross Jupiter on Monday, December 30 between 7:19 pm and 9:49 pm EST (or 00:19 to 02:49 GMT on Tuesday). Io and its little shadow cross Jupiter on Tuesday, December 31 between 11:12 pm and 1:21 am EST (or 04:12 to 06:21 GMT on Wednesday).

Very bright and red Mars will clear the trees in the east around 7:30 pm local time, then cross the sky all night long behind Jupiter and Uranus, and end up in the lower part of the western sky before dawn. In a telescope, the planet will display a small, rusty-coloured disk and some darker markings. The surface details will sharpen while Mars gets closer to Earth every day until its opposition night on January 15-16. This week we’re about 98 million km apart. Although Mars is creeping retrograde west in Cancer (the Crab), it’ll be less than a fist’s diameter below the bright star Pollux, the lower of the “twin” stars of Gemini.

If you are a person who crawls under the covers early each night, the speedy planet Mercury should be easy to see for one more week while it shines at a bright magnitude -0.4 above the southeastern horizon before sunrise. At mid-northern latitudes the planet will rise around 6:15 am local time. Scorpius’ bright star Antares will be sparkling a fist’s width to the planet’s right (or 9 degrees to the celestial SSW). In a telescope Mercury will exhibit a 75%-illuminated, waxing gibbous phase that will be “swimming” due to the extra air we are looking at it through. But you should still be able to make out its out-of-round shape. Turn optics away from the horizon before the sun starts to rise.

Public Astronomy-Themed Events

Every Monday evening, York University’s Allan I. Carswell Observatory runs an online star party – broadcasting views from four telescopes/cameras, answering viewer questions, and taking requests! Details are here. They host in-person viewing on the first clear Wednesday night each month. Other Wednesdays they stream views online via the observatory YouTube channel. Details are here.

On Wednesday evening, January 1 at 7:30 pm EST, the RASC Toronto Centre will livestream their free, public Recreational Astronomy Night Meeting at https://www.youtube.com/rasctoronto/live. Talks will include The Sky This Month and visual stargazing. Details are here.

Keep your eyes on the skies! I love getting questions and requests. Send me some!