Merry Perihelion, the Dipper Drops Meteors, Plenty of Planets, and the Waning Moon to Morning Shows the Bull Best!

This amazing composite image by Detlef Hartmann shows the continued expansion of the Crab Nebula Supernova Remnant (aka Messier 1) in Taurus over 10 years (Sept 29, 2008 through Sept 22, 2017). It spans about 0.1 degrees of the sky. In the heart of the nebula sits a rapidly rotating neutron star that emits radio waves. They sweep across our detectors 30 times per second light a fast lighthouse’s beam. The intense radiation causes the gas in the cloud to glow. Detlef’s original image can be viewed at Astrobin https://www.astrobin.com/327338/0/

Happy New Year, Stargazers!

Here are your Astronomy Skylights for the week of December 31st, 2023 by Chris Vaughan. Feel free to pass this along to your friends and send me your comments, questions, and suggested topics. You can also follow me on Twitter as @astrogeoguy! Unless otherwise noted, all times are expressed in Eastern Time. To subscribe to these emails please click this MailChimp link.

If you’d like me to bring my Digital Starlab portable inflatable planetarium to your school or other daytime or evening event, or deliver a session online, contact me through AstroGeo.ca, and we’ll tour the Universe, or the Earth’s interior, together! My book with John A. Read entitled 110 Things to See With a Telescope is a guide to viewing the deep sky objects in the Messier List – for both beginners and seasoned astronomers. DM me to order a signed copy!

Earth will reach its closest approach to the sun on Tuesday. The moon will move out of the evening and into morning this week while it wanes through third quarter. That will allow us to enjoy both bright and fainter planets in evening and set up some nice photo ops with the moon and Venus and Mercury before sunrise. The Quadrantids meteor shower will peak under some moonlight on Thursday morning. Finally, I highlight the bright and ancient stars we know as Taurus. Read on for your Skylights!

Merry Perihelion!

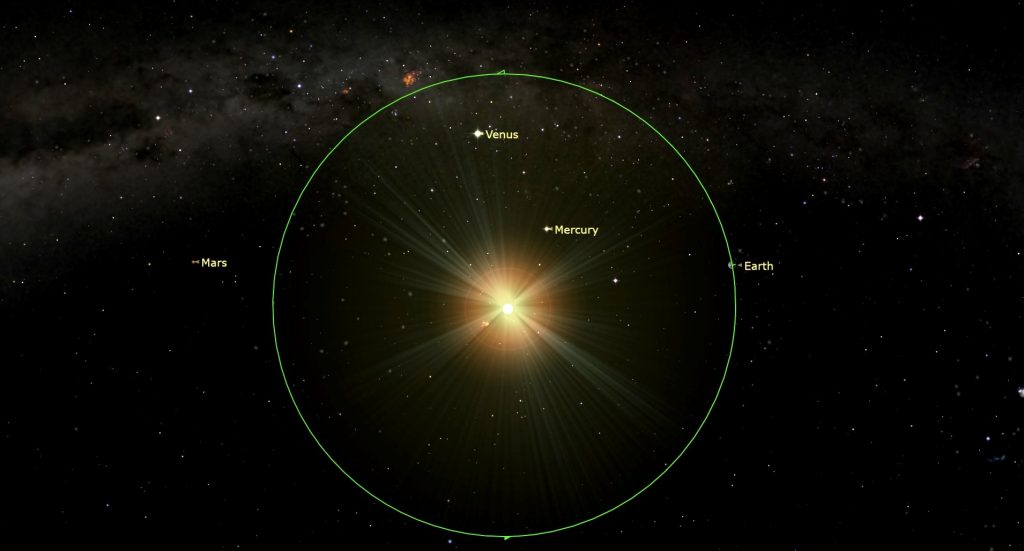

On Tuesday, January 2 at 8 pm EST or 5 pm PST 16:00, the Earth will arrive at perihelion, its minimum distance from the sun for the year. The worldwide event converts to 01:00 Greenwich Mean Time on January 3. At perihelion Earth will be 147.101 million km from our star – or 1.67% closer than our mean distance of 1.0 Astronomical Unit (or 1.0 A.U.).

Earth’s distance from the sun varies throughout the year because our orbit is elliptical enough to varying the Earth-sun distance by 3.3%. We don’t feel warmer at perihelion. As winter-chilled Northern Hemisphere dwellers will attest, daily temperatures on Earth are not controlled by our proximity to the sun, but by the number of hours of daylight we experience, which is only about 9 hours at this time of the year in the Great Lakes region. The date of perihelion varies by a few days due to the extra quarter of a day in a solar year. The drift gets fixed by adding extra days on Leap Years, of which 2024 is one.

Care for a Quick Meteor Shower?

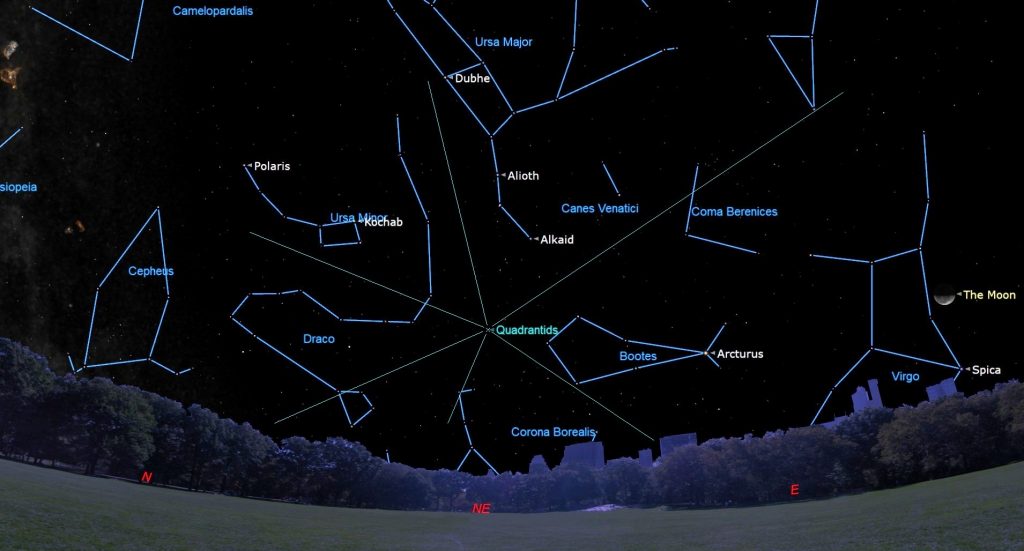

Named for a now-defunct, northerly constellation called Quadrans Muralis (the Mural Quadrant), which used the stars in northern Boötes (the Herdsman), the Quadrantids meteor shower occurs every year from December 30 to January 12. But this particular shower’s most intense period, when 50 to 100 meteors per hour can occur, lasts for only about 6 hours surrounding the peak, which will occur on Thursday, January 4 at 09:00 Greenwich Mean Time. That converts to 4 am EST and 1 am PST in the Americas. You will only see that many meteors if your skies are both clear and dark during all or part of the 6-hour window. This year that will be observers from North America to Eastern Asia! Realistically, expect to catch about a meteor per minute, at best.

Meteor showers occur when Earth passes through a cloud of tiny particles in space that were deposited over time by the repeated passages of an asteroid or periodic comet, in this case an asteroid designated 2003EH. When the particles strike our upper atmosphere at tremendous speed, they ionize the air molecules along a 1-metre-wide zone that can stretch for kilometres – producing the streaks of light we see overhead as meteors. Quadrantids commonly produce bright fireballs because its particles are stony and also burn up, adding to the spectacle. The duration of a shower depends on how quickly Earth gets through the cloud. The intensity is controlled by the particle density and whether we plough through the core or skirt its edge.

The meteors of any shower will appear to radiate from the part of the sky overhead that is pushing into the debris cloud, like bugs on a moving car’s windshield. The Quadrantids’ radiant lies beyond the tip of the Big Dipper’s handle. Meteor showers are usually worldwide events – but this one’s very northerly radiant will not climb above the horizon for observers in the Southern Hemisphere, reducing the numbers for them. Meteor-watchers near the equator will only see the half of the streaks not blocked below the Earth’s horizon and the hours of true darkness are few in January.

The optimal time for viewing Quadrantids in North America will be from midnight to dawn on Wednesday, while the shower’s radiant will be climbing the northeastern sky. Since a third quarter moon will clear the eastern treetops around 2 am local time that morning, the optimal time for viewing Quadrantids meteors in the Americas will be around midnight.

To see the most meteors, find a safe, wide-open, dark location, preferably away from light polluted skies, and just look up with your unaided eyes. If possible, sit where the moon is blocked by something. The fields of view of binoculars and telescopes are too narrow to be useful for meteors. Don’t spend too much time watching the radiant because the meteors appearing near that location will be short – but do take note of whether they can be traced backwards to the radiant. You might see some brief flashes of light near the radiant, though. Try not to look at your phone’s bright screen – it’ll ruin your night vision. Just keep your eyes heavenward – even while you are chatting with companions. Don’t forget to bundle up, and good luck!

The Moon

Following the bright moon at Christmas, stargazers worldwide will have increasingly darker skies during evening this week while our natural night-light wanes and rises later.

Tonight (Sunday) the still-bright, waning gibbous moon will rise in mid-evening among the stars of Leo (the Lion). You should be able to see Leo’s brightest stars above the moon, especially Regulus. The moon will rise about an hour later each night and linger an hour longer into the morning daytime sky. The moon will still reside in Leo on Monday night. On Tuesday the moon will rise just before midnight.

The moon will enter the stars of Virgo (the Maiden) on Wednesday. Early risers on Wednesday morning can watch the moon pass in front of, or occult, some of her stars. For those in the southern USA and Mexico, the moon will occult the bright star Zaniah or Eta Virginis starting around 3:45 am Central Time. Sometime later the star will pop into view again when it emerges from behind the moon’s dark limb. Depending on your location northern pole region of the moon will graze the star or the bulk of the moon will cross Zaniah. Sharp eyes, binoculars, or telescopes will show the event. The moon will also occult Zaniah’s companion star named 13 Virginis. If you live farther north, including the Greater Toronto Area, use binoculars to watch 13 Virginis disappear and re-appear between 4:30 and 5:10 am EST while Zaniah stays in sight.

The moon will complete three quarters of its orbit around Earth, measured from the previous new moon, on Wednesday at 10:30 pm EST or 7:30 pm PST, which converts to 03:30 GMT on January 4. At the third (or last) quarter phase the moon appears half-illuminated, on its western, sunward side. It will rise around midnight local time, and then remain visible until it sets in the western daytime sky in early afternoon.

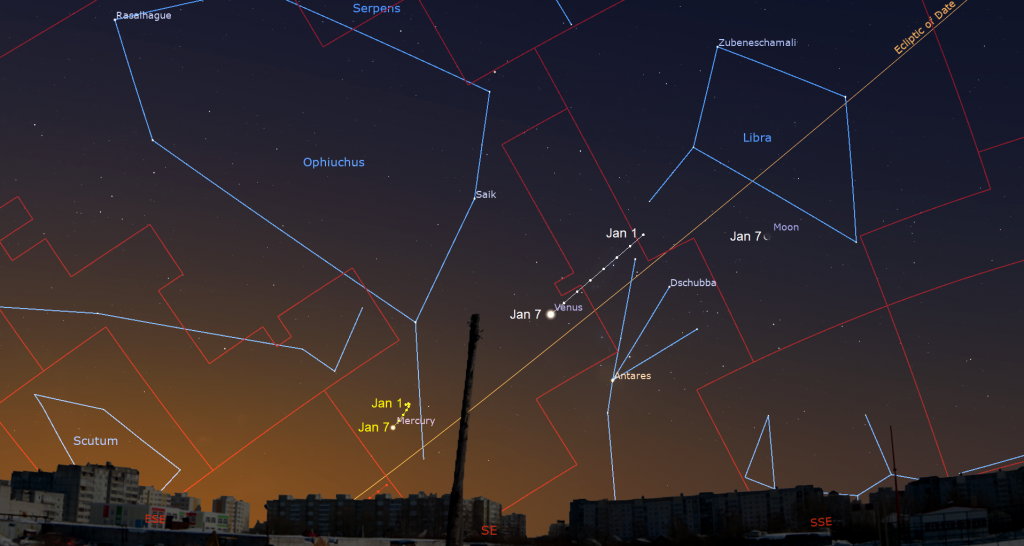

For the rest of the week, the moon will only shine in the sky after midnight, accompanying bright Venus in the hours before sunrise. Thursday morning’s plump crescent will shine near Virgo’s brightest star Spica. The moon will enter Libra (the Scales) for the coming weekend, when it will form a nice alignment with Venus and Mercury if you head out around 7 am local time. Take a picture!

The Planets

Four planets are available for your after-dinner viewing pleasure this week – two are bright and easy to see and two are fainter and more challenging, but do-able. No moonlight will help with that.

The early sunsets are allowing us to continue seeing Saturn every night, even while it is being carried west and sunward by about 3.5 minutes’ worth, and setting earlier, each night. Saturn’s prominent pale yellow-tinted dot will pop into view in the lower part of the south-southwestern sky shortly after sunset. That will be its best telescope viewing time because the planet will already be descending to set around 9 pm local time. Once the sky fully darkens, the modest stars of Aquarius (the Water-Bearer) will appear above Saturn (or to the celestial east).

Powerful binoculars can hint that Saturn has rings, but any size, style, or brand of telescope will let you see them easily. A better quality of telescope will show them more clearly. From Earth, Saturn’s axial tilt of 26.7° is letting us see the top of its ring plane, which will narrow more every month until March of 2025. It will also allow its brighter moons to array themselves above, below, and to either side the planet. Saturn’s largest and brightest moon Titan never wanders more than five times the width of Saturn’s rings from the planet. The much fainter moon named Iapetus can stray up to twelve times the ring width during its 80-day orbit of Saturn. The next brightest moons Rhea, Dione, Tethys, Enceladus, and Mimas all stay within one ring-width of Saturn.

During this week, Titan will migrate counter-clockwise around Saturn, moving from the upper left of Saturn (or celestial east) tonight, crossing closely below Saturn on Friday, and then to the lower right of the planet (or celestial west) next Sunday night. (Remember that your telescope will probably flip the view around.) The rest of the moons will be tiny specks. You may be surprised at how many of them you can see through your telescope if you look closely. As we approach that edge-on ring plane, some of the moons and their shadows will be crossing Saturn’s globe.

The far fainter ice giant planet Neptune has been following Saturn across the sky every night. On this week’s moonless evenings the magnitude 7.9 planet can be observed in good binoculars and backyard telescopes. This week Neptune will be located 2.2 fist diameters to Saturn’s upper left, or 21.9° to its celestial east-northeast. Saturn’s faster orbital notion will allow the planet to creep closer to slower Neptune over time. Next summer/fall, they’ll be half as far apart, and for 2025 they’ll share the view in binoculars, and even in telescopes for a while in August! How cool is that!

Neptune will set at about 11 pm local time, so plan to look at Neptune as soon as it gets dark, while the planet is higher and appears crisper in your telescope. You can place, Lambda Piscium and Kappa Piscium, the lowest two stars of the circlet of Pisces (the Fishes), just outside the top of your binoculars’ field of view and look for blue Neptune near the bottom of the field. Or, search less than a binoculars’ field width to the right (or celestial west) of the box formed by the four medium-bright stars 27, 29, 30, and 33 Piscium.

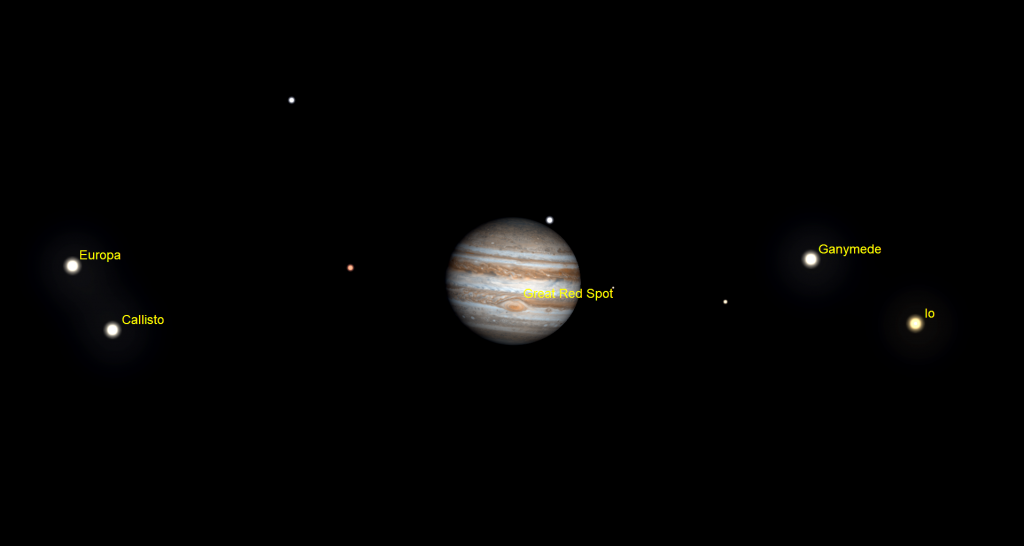

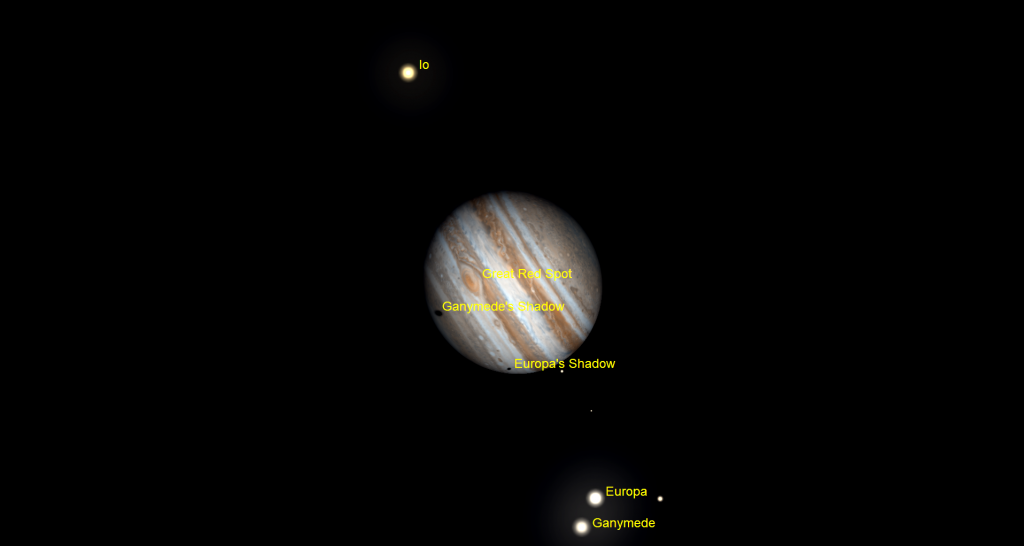

Jupiter will be the easiest planet to see every night. Its extremely bright, white dot will be a beacon in the southeastern sky at dusk. Even binoculars can show you Jupiter’s four largest Galilean moons aligned on both sides of the planet. Named Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto in order of their orbital distance from Jupiter, those moons complete orbits of the planet every 1.7, 3.6, 7.2, and 16.7 days, respectively. If you see fewer than four moons, then one or more of them is crossing in front of or behind Jupiter, or hiding in Jupiter’s dark shadow – or two of the moons are very close together or occulting one another. In the Americas, the moons will pair up beside Jupiter on Tuesday and Wednesday evening, only Callisto will be visible around 6 pm EST on Saturday (Io and Ganymede will be on Jupiter’s disk and Io will be occulted behind the planet), and all four moons will be huddling to Jupiter’s right next Sunday evening.

This week Jupiter will be rising in mid-afternoon, climbing to its highest and best telescope-viewing position around 8 pm local time, and then setting in the west by about 2:30 am. Watch for the two brightest stars of Aries (the Ram) named Hamal and Sheratan shining a generous fist’s diameter above Jupiter. The stars forming the Great Square of Pegasus will be higher and to the right.

Any small, decent quality telescope can show you Jupiter’s dark belts and light zones, which are aligned parallel to its equator. With a better grade of optics, Jupiter’s Great Red Spot, a cyclonic storm that has raged for hundreds of years, is visible for several hours when it crosses the planet every 2nd or 3rd night. For observers in the Americas, the GRS will cross Jupiter’s disk in mid-evening Eastern Time tonight (Sunday), on Tuesday, Thursday, and next Sunday. It’ll appear late on Monday, Wednesday, and Saturday night, and also during the wee hours of Thursday and Saturday morning. The spot has been rather pale pink for some time now. If you have any coloured filters or nebula filters for your telescope, try enhancing the spot with them.

From time to time, the small, round, black shadows cast by Jupiter’s Galilean moons become visible in amateur telescopes when they cross (or transit) the planet’s disk. For those in the Americas, Io’s shadow will cross Jupiter on Friday, January 5 from 9:50 to 11:55 pm EST (or 02:50 to 04:55 GMT on Saturday). On Saturday evening, January 6, two shadows will cross the southern hemisphere of Jupiter while the Great Red Spot appears at the same time. At 9:18 pm EST, the large shadow of Ganymede will join the much smaller shadow of Europa, which began its own crossing of the planet’s south polar zone at 7:36 pm EST. The Great Red Spot will rotate into view by 8 pm EST. Europa’s shadow will leave Jupiter at 9:56 pm EST, leaving the spot and Ganymede’s shadow to continue on until 11 pm EST. (These times may vary by a few minutes, and other time zones of the world will have their own crossings.)

Like Neptune with Saturn, Uranus is pursuing Jupiter every night. This week Uranus will be positioned 1.4 fist diameters to Jupiter’s left (or 14° to its celestial ENE). Since Uranus will be setting around 4 am local time, about 75 minutes after Jupiter, it will be available for viewing during most of the night.

The bright Pleiades star cluster will also be located a generous fist’s width to Uranus’ upper left (or 11.5° to its celestial northeast). Magnitude 5.7 Uranus is normally quite easy to see in binoculars and backyard telescopes under moonless conditions – some people have even been able to spot the planet with their unaided eyes. Use binoculars to find the medium-bright star Botein between Jupiter and the Pleiades. The blue-green speck of Uranus will appear several finger widths to its lower right.

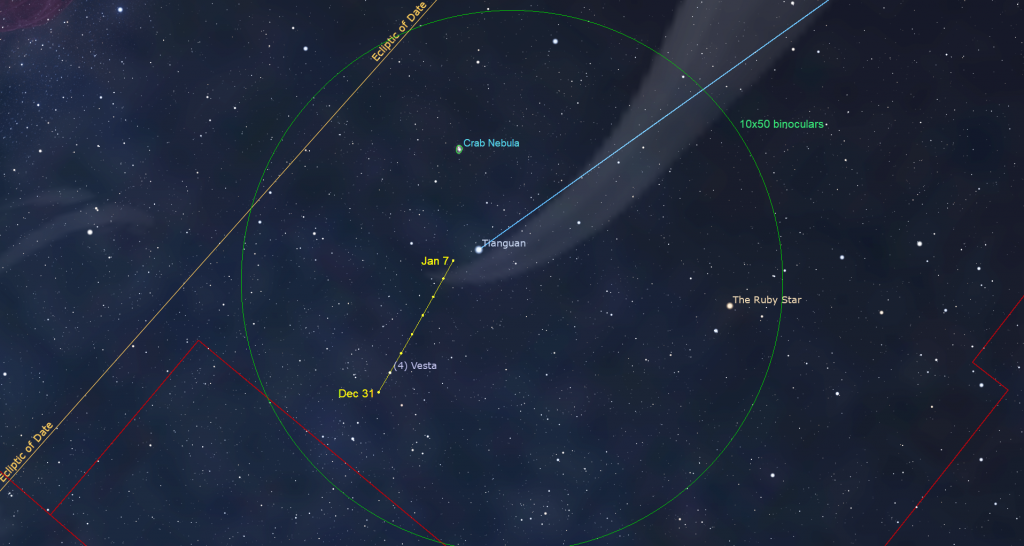

Have you wanted to see an asteroid? The large, main belt asteroid named (4) Vesta will be approaching the medium-bight star Zeta Tauri (aka Tianguan), the lower horn tip star of Taurus (the Bull) this week. At magnitude 6.4, Vesta is brighter than Neptune and almost as bright as Uranus. Tonight (Sunday) it will be located a bit more than a thumb’s width to the lower right of the star. Each night it will creep closer, getting close enough to Zeta for them to share the view in any telescope from Tuesday onwards. I’ll post Vesta’s nightly position here.

Over in the morning sky, Venus, the brilliant planet continues to blaze away in the southeastern sky every morning. Catch it from the time when it rises, around 5 am, until sunrise. The planet will drop a little lower each morning as its orbit returns it sunward. If you head out for a look before the sky brightens on a few mornings this week, you can detect Venus’ motion compared to the bright star Antares below it. Viewed through a telescope this week, our next-door planet will show a shrinking, waxing gibbous disk spanning 13.9 arc-seconds.

Mercury will spend all of January visible in the pre-dawn eastern sky – with far brighter Venus gleaming to its upper right (or celestial west). As the month opens, the medium-bright, magnitude 0.43 planet will rise just before 6:30 am local time and exhibit a pleasing crescent form under magnification. Mercury will rise earlier and increase its angle from the sun each morning until it reaches greatest elongation 23.5 degrees west of the sun on January 12. Mercury will be north of the ecliptic then, producing an excellent apparition for observers at the tropics and at mid-northern latitudes and good views for those viewing it from south of the equator. Mid-northern observers can spot the planet in a dark sky around 6:30 am and then watch it climb higher for almost an hour. For eye safety, turn all optics away from the eastern horizon before the sun rises.

Mars will become visible before sunrise next month.

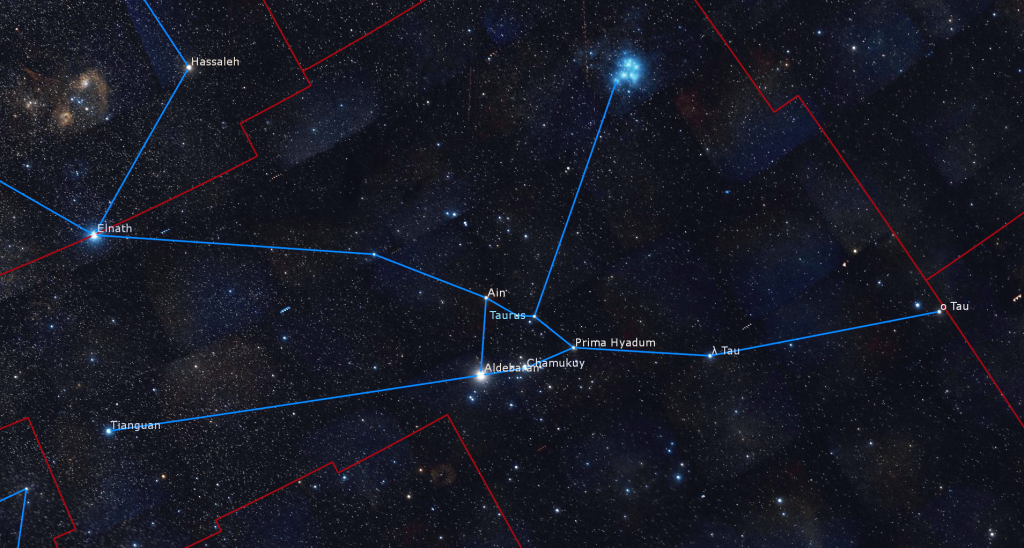

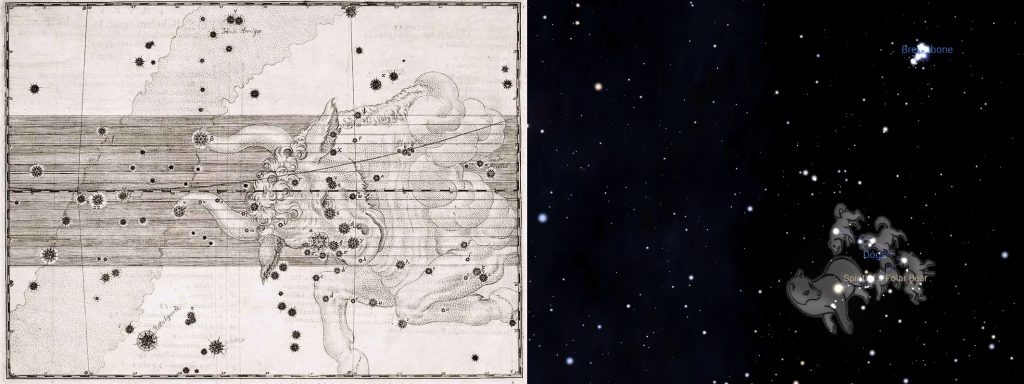

The Bull’s Best

January evenings feature a group of bright and distinctive constellations that are easy to recognize with unaided eyes, and which make winter nights in the Northern Hemisphere worth waiting for. They include Taurus (the Bull), Orion (the Hunter), Auriga (the Charioteer), and Gemini (the Twins). The Winter Milky Way passes through those constellations – populating them with countless delights to view in binoculars or backyard telescopes on moonless nights. Because the evening skies will be nice and dark this week and next, I’ll guide you through the best sights to see in Taurus. In future Skylights, we’ll tour the other three constellations.

The distinctive constellation of Taurus (the Bull) is perfectly placed for evening exploration in January. It is already halfway up the eastern sky after darkness falls and it crosses the sky for almost the entire night. Taurus contains many wonderful objects to observe in binoculars, and in small or large telescopes – from spectacular star clusters to a supernova remnant, and more. Let’s talk about some of its treats you’ll spy during a winter stroll, and others that make setting up your telescope on a cold winter evening worth your while.

The constellation of Taurus is located on the ecliptic and just north of the celestial equator, making it visible almost globally. With the dim constellations of Cetus (the Whale), Aries (the Ram), and Aquarius (the Water-Bearer) positioned just to the west of it (on the right), Taurus’ much brighter stars make quite an improvement upon them. Taurus also borders on Orion (the Hunter), Auriga (the Charioteer), and Gemini (the Twins). Being situated on Taurus’ left-hand (eastern) side, they rise later in the evening. Perseus (the Hero) is to the north. To Taurus’ lower right (or celestial southwest) you’ll find the rather faint and winding constellation of Eridanus (the River).

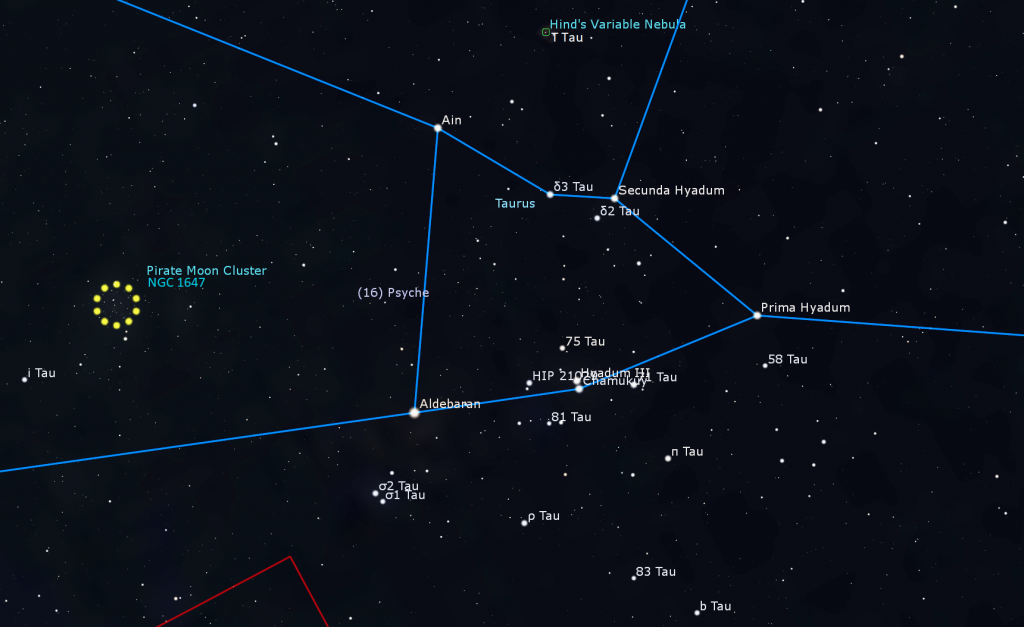

Taurus’ boundary covers a square area of sky that measures about 3.5 fist diameters on each side – except for the southeast quadrant, which has been given over to Orion. Taurus is dominated by several elements that combine to make the bull take form. A large, triangular arrangement of stars form the bull’s face. A very bright, reddish star named Aldebaran sits at the southeastern (lower left) vertex of the triangle, marking his baleful eye. He’s literally seeing red! Two medium-bright stars sitting 1.5 fist diameters to the lower left (east) of his face mark the tips of his horns. Well above the face, the Pleiades star cluster sparkles above his hunched shoulders – and to the southwest, a handful of less prominent stars form his chest and forelegs. The rest of him is missing. When Taurus rises in the east, he is tilted sideways, with his horns down and legs extended – as if he’s charging the twins of Gemini. He doesn’t tilt upright until he enters the western half of the sky near midnight.

Taurus’ very distinctive shape has been recognized since ancient times. It was one of the first constellations to be described. At that time, the spring equinox occurred while the sun was in Taurus. (You can see this by setting an astronomy app’s date to noon on April 9, 2250 BC.) The bull’s strength and fertility were featured in ancient Babylonian and Sumerian myths and legends. In the Mesopotamian Epic of Gilgamesh, the bull was sent to kill Gilgamesh, who is probably represented by Orion’s stars.

In Greek mythology, Taurus represented Zeus in disguise, seeking to abduct lovely Europa who was charmed by the animal’s power and beauty. It may also have been the Cretan Bull which Hercules slew during his twelve labours. In the Inuit traditions of the far north, Aldebaran represents a polar bear, and the rest of the stars in the triangle are dogs keeping him at bay. The Maori view the stars extending from Orion’s Belt upwards through Taurus to the Pleiades as Te Rā o Tainui, the mast and triangular sail of Tainui’s ocean-going war canoe.

Taurus’ triangular face is actually one of the nearest open star clusters to us. Located only about 150 light years away from the sun, it’s called The Hyades. The cluster is named for the daughters of Atlas in Greek mythology, who were associated with rain when they wept for their slain brother Hyas. The cluster actually contains several hundred stars, with a half-dozen or so readily seen under moonless, suburban skies. It’s a lovely target to view in binoculars. Many of its stars are close pairs that astronomers call double stars. By the way, Aldebaran is not part of the cluster. It is less than half as far away! Many groups interpreted the V-shape of Taurus as a jaw-bone.

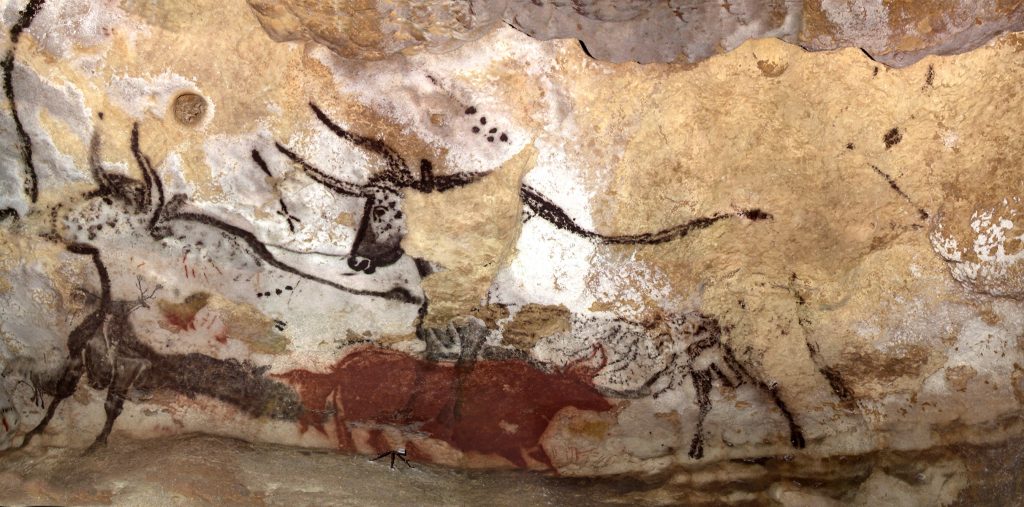

There is a remarkable theory that the stars of Taurus, and nearby Orion’s belt, were incorporated into the ancient paintings found on the Caves of Lascaux in Southern France. The paintings were created somewhere between 8,000 and 17,000 years ago. On the ceiling of the “Salle des Taureaux” or Room of the Bulls, are very large color paintings of horned bulls, one of which has dark facial spots approximating the Hyades, plus a grouping of six stars where the Pleiades should be, and a line of stars resembling Orion’s belt. Even the horns are placed where their stars are found. It’s wonderful to imagine early humans capturing the night sky for posterity!

This week, Taurus will rise in mid-afternoon local time, climb high into the southern sky around 10 pm, and then descend westward to set around 5:30 am local time. After dusk, you can find him by continuing the line formed by Orion’s belt westwards (upwards in early evening, or to the right later on) by about two outstretched fist diameters (or 20°) until you reach bright Aldebaran. If Orion hasn’t risen yet, you can look high in the east for the little cluster of blue stars of the Pleiades and find Taurus about a fist’s diameter below them (or 12° to the celestial southeast).

Aldebaran, which means “follower” in Arabic because it chases the Pleiades across the sky, is the brightest star in Taurus. It’s an old orange giant located 65 light-years away from us. Somewhat cooler than our sun, it’s more than twice as massive and 44 times the sun’s diameter because it has exhausted its core Hydrogen and has swelled as it prepares to die. Aldebaran’s position near the ecliptic means that it is frequently occulted (covered) by the moon and visited by the planets as they traverse their orbits.

The beautiful star cluster known as the Pleiades, or the Seven Sisters, which sits about one and a half fist widths above the bull’s face, is one of my favorite wintertime objects. It’s also designated Messier 45 (or M45), part of Charles Messier’s famous list of comet-like objects. The Pleiades is made up of the young, hot blue stars named Asterope (“A-STER-oh-pee”), Merope, Electra, Maia, Taygeta, Celaeno, and Alcyone. And those stars are indeed related – born of the same primordial gas cloud. In Greek mythology, they were the daughters of Atlas, and half-sisters of the Hyades. Only five or six of the sister stars are usually seen with unaided eyes – plus their parent stars Atlas and Pleione huddled together at the east end of the grouping.

The Pleiades cluster is located about 450 light years away from the sun, and it, too makes a wonderful target in binoculars or a telescope at low magnification, where many more siblings are revealed! A large telescope under dark skies will also reveal blue nebulosity around the stars – reflected light from unrelated gas and dust that the stars are passing through. Galileo was among the first to observe the cluster in a telescope. In 1610, he published a sketch made at the eyepiece.

The Pleiades cluster is located about 450 light years away from the sun. The cluster’s stars are mainly hot, young, blue-white spectral class B giants and sub-giants that formed together about 100 million years ago. The object is best observed in a widefield telescope at low magnification, which can reveal up to 500 stars within a 2 degree field – many of them doubles and multiples. The cluster is passing through a dusty region of the galaxy. This proper motion will eventually carry the cluster below Orion’s feet. The light from the brightest stars reflects off the dust and produces a blue halo around them. That nebulosity is visible in large aperture telescopes and long exposure photographs.

Not surprisingly, many cultures, including Aztec, Maori, Sioux, Hindu, and more, have noted this object and developed stories around it. Many indigenous groups saw the Pleiades as the doorway in to the afterlife, or the portal through which humans first fell to Earth – naming it the Hole in the Sky. In Japan, it is called Suburu (スバル in katakana), and forms the logo of the eponymous car maker. Due to its similar shape and diminutive size, some people mistake the Pleiades for the Little Dipper. While the shapes are similar, the Little Dipper is twenty times larger than the Seven Sisters!

The star Elnath, or Alnath, which translates to “the butting one”, is an old, bright, hot blue giant star located 130 light-years away from our sun. It marks the bull’s higher (more northerly) horn tip. On the border of Taurus and Auriga (the Charioteer), it’s one of only two stars in the sky that are shared by two constellations. (The other is Alpheratz in Andromeda/Pegasus.)

The bull’s lower horn tip star is less bright, but is still readily seen by eye. It was once referred to as Shurnarkabti-sha-shūtū “the star in the bull towards the south”, but nowadays it’s simply called Zeta Tauri (ζ Tau) or Tianguan. This star is a hot blue sub-giant – 420 light-years away, but radiating 6,700 times the light of our sun. Zeta is a candidate to explode one day in a supernova burst – ironic since it sits very close to a supernova remnant, the Crab Nebula (more on this below).

The Hyades contains a number of nice double stars. Two degrees to the right of Aldebaran (towards the bull’s chin), look with unaided eyes or binoculars for the close-together pair of stars designated Theta 1 and 2 Tauri. The higher one is slightly more yellow. Also easy, on the opposite cheek are three widely spaced stars all designated Delta Tauri. Some apps label them as Hyadum II, Delta 2, and Cleeia or Delta 3. A finger’s width below Aldebaran, hunt with binoculars for the close pair of white stars named Sigma 1 and 2.

Here are a few more interesting objects to hunt for if you have a large telescope. The dim star named 47 Tauri sits about a fist’s diameter to the lower right (or 9 degrees to the celestial southwest) of Aldebaran. It’s a close pair of unevenly bright yellow stars. Farther west, look for T Tauri, a very young star recently formed and still surrounded by some of its protostellar disk, often named Hind’s Variable Nebula. Lambda Tauri is a fairly bright star located five degrees to the lower right of the bull’s chin. This is an eclipsing binary variable star that dims in brightness for 1.1 days every 4 days because it has an orbiting dim companion star that blocks some of the main star’s light when it crosses between us and the star. Some apps label it as Elthor “the bull”.

The supernova remnant now known as the Crab Nebula (or Messier 1) sits a finger’s width above Zeta Tauri. Nowadays, you need a very large telescope to see the remnant as a dim, fuzzy patch – but on July 4, 1054 AD Chinese astronomers recorded that the star that exploded to create the Crab Nebula shone bright enough to see it in the daytime for three weeks! Then it faded to become the brightest night time star for a few months. The object is about 6,500 light-years from the sun.

Here’s one more treat. A very red, magnitude 4.3 star named the Ruby Star (or 119 Tauri) sits 2.7 finger widths to the right of Zeta Tauri. It’s a variable star that pulsates every 165 days. There are even more sights to see in Taurus. You should be able to find it easily in binoculars.

The open star clusters NGC 1746 and NGC 1647 sit between the bull’s horns. A close-together pair of clusters NGC 1817 and NGC 1807 sit two finger widths below the mid-point of the line connecting Zeta Tauri and Aldebaran. The outer rim of the Milky Way passes just beyond Taurus’ horn tips, and that area will reward scanning with binoculars or telescope, too.

Public Astronomy-Themed Events

Every Monday evening, York University’s Allan I. Carswell Observatory runs an online star party – broadcasting views from four telescopes/cameras, answering viewer questions, and taking requests! Details are here. They host in-person viewing on the first clear Wednesday night each month. Other Wednesdays they stream views online via the observatory YouTube channel. Details are here.

On Wednesday evening, January 3 at 7:30 pm EDT, the RASC Toronto Centre will host their free, public, in-person monthly Recreational Astronomy Night Meeting in the Gemini East Room at the Ontario Science Centre. The meeting will also be live streamed at https://www.youtube.com/rasctoronto/live. Talks include The Sky This Month and more imaging through a Dobsonian telescope. Details are here.

Keep your eyes on the skies! I love getting questions and requests. Send me some!