Mid-Spring’s Full Milk Moon Spoils Stargazing and Attenuates the Eta-Aquariids, Evening Venus and Mars, and Ursae Musing!

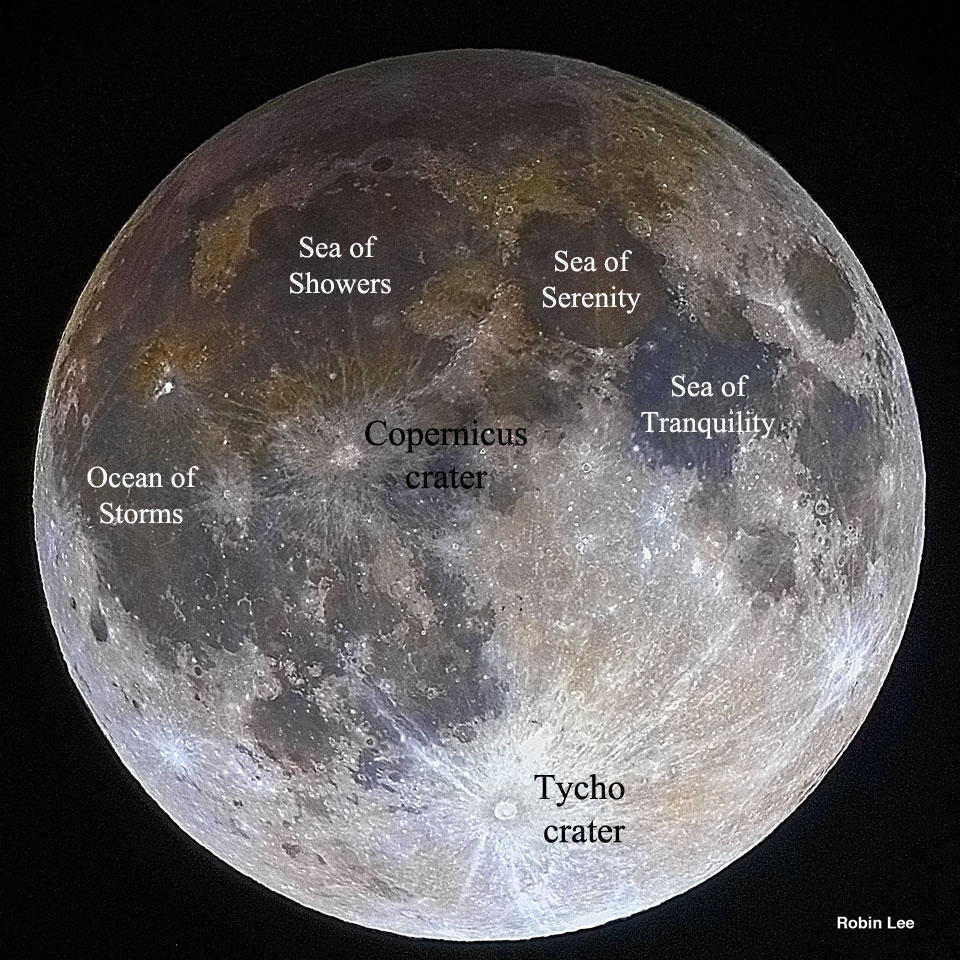

This colour image of the moon during the penumbral lunar eclipse of September 16, 2016 was taken by Robin Lee in Hong Kong. It was the NASA Astronomy Picture of the Day for Oct 12, 2016.

Welcome to mid-Spring, Stargazers!

Here are your Astronomy Skylights for the week of April 30th, 2023 by Chris Vaughan. Feel free to pass this along to your friends and send me your comments, questions, and suggested topics. You can also follow me on Twitter as @astrogeoguy! Unless otherwise noted, all times are expressed in Eastern Time. To subscribe to these emails please click this MailChimp link.

If you’d like me to bring my Digital Starlab portable inflatable planetarium to your school or other daytime or evening event, or deliver a session online, contact me through AstroGeo.ca, and we’ll tour the Universe, or the Earth’s interior, together! My terrific book with John A. Read entitled 110 Things to See With a Telescope is a guide to viewing the deep sky objects in the Messier List – for both beginners and seasoned astronomers. DM me to order a signed copy!

Middle of Spring is here for northerners. The bright moon will dominate the night sky worldwide this week, so take a closer look at it! The minor Eta-Aquariids meteor shower will peak while the moon is bright, but keep an eye out for some bright ones. The bright moon won’t prevent us from seeing the two dippers, so I guide you through their stars and teach you how to measure sky angles with them. Venus and Mars will be the only bright planets in evening, the minor planet Ceres will be near the lion’s tail, and Saturn will be easy to see before sunrise. Read on for your Skylights!

A New Astronomy Website!

Hey, everyone! If you, like me, are already missing SkyNews Magazine and its website, the former editor of SkyNews, Carina Ockedahl, has launched a new website called Astronomy by Night that caters to the amateur astronomy community in Canada. It offers news, features, astrophotography and observing articles, gear and tech reviews, profiles, columns, videos, podcasts, and a weekly newsletter. I’m a contributor, too. Since Carina has roots in Québec, she plans to include some French language content! Check it out at https://www.astronomybynight.ca/ and I’ll see you there!

May Day

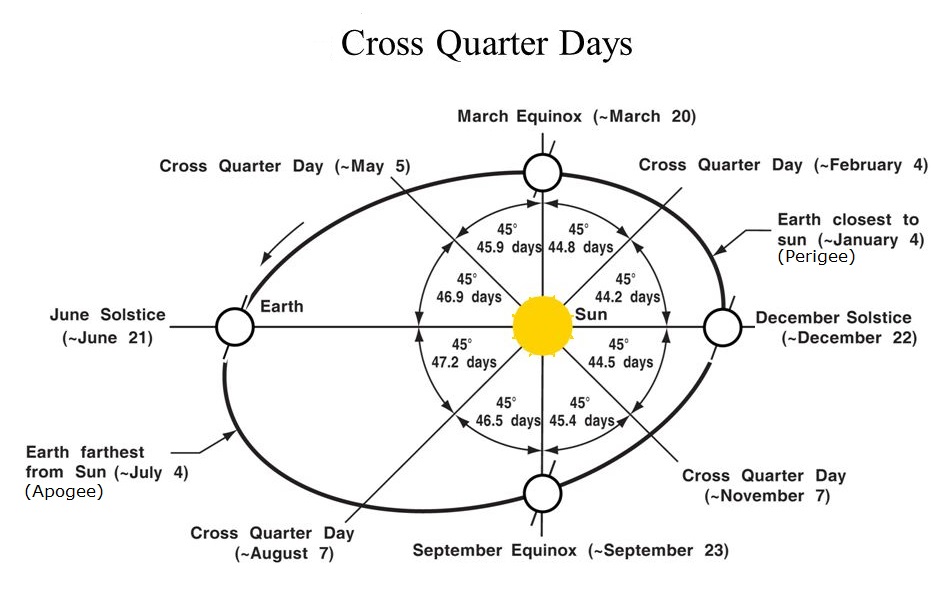

Friday, May 5 will be May Day! That date is one of the four so-called astronomical cross-quarter days, which are the midpoints between the solstices and equinoxes. May 5 is exactly midway between the vernal equinox and the summer solstice – so the weather will definitely start being less spring-like and more summer-like after this week.

We can’t merely divide our 365.25-day year into four 91.3-day-long seasons and then count half that many days to reach the cross-quarters. Planets with elliptical orbits move faster when they are closer to the sun and slower when they are farther away. Since Earth is moving slower at aphelion in July, summer in the Northern Hemisphere is 93.6 days long, about five days longer than winter’s 89.0 days. Spring is 92.8 days long, leaving autumn at 89.8 days.

May Day celebrations focus on romantic love, fertility in nature, and the arrival of spring flowers. In contemporary paganism, the day is called Beltane. An old Irish tradition for it involved “Lucky Fire” leaping! In roman times the Maiouma festival honoured Dionysus and Aphrodite.

The cross-quarter dates vary a little each year due to leap years and other factors. The other three cross-quarter days in 2023 are Imbolc on February 3 (which we observe as Groundhog Day every February 2), Lughnasath or Lammas on August 7 (which we associate with Mid-Summer’s Eve), and Samhain on November 7. I think you can guess which spooky “holiday” that last one connects to. For residents of the Southern Hemisphere, where the seasons are swapped from the Northern Hemisphere, each of those festivals is offset by twelve months.

The “holidays” tend to be observed several days before the real astronomical cross-quarter because their dates were established hundreds or thousands of years ago. Since then, the precession, or slow wobble, of Earth’s axis of rotation has shifted the sun along the ecliptic, altering the dates when the sun reaches the solstices and equinoxes.

The Moon

Earthlings worldwide will be seeing a lot of the bright moon this week. Our natural nightlight will be shining brightly nearly all night long until the coming weekend, when observers at mid-northern latitudes will be granted about an hour of darkness between dusk and moonrise. Since the moon will wash out everything but the bright stars, check out the best things to see on a mostly full moon itself.

Tonight (Sunday) the 79%-illuminated waxing gibbous moon will rise around mid-afternoon – making it relatively easy to see with your unaided eyes and in binoculars or telescopes in a bright sky for a while before sunset. The moon will be in the southeastern sky. Even though that’s on the opposite side of the sky from the sun, be sure to keep any optics pointed well away from the west until the sun has completely set (after 8 pm local time). The same will hold for Monday and Tuesday, too. On Sunday evening the brightest stars of Leo (the Lion) should be visible above the moon.

The bright waxing moon will spend Monday to Thursday traveling the lengthy form of Virgo (the Maiden). On Tuesday, look for the nice double star named Porrima sparkling just a finger’s width above (or about 1° to the celestial north of) the moon. (You can still view double stars while the bright moon is out. In this case, try hiding the moon just beyond your telescope’s field of view.) On Wednesday night, the nearly full moon will shine two finger widths above Virgo’s brightest star, Spica.

The moon will officially reach its full moon phase on Friday, May 5 at 1:34 pm EDT, 10:34 am PDT, or 17:34 Greenwich Mean Time. Full moons in May always shine in or near the stars of Libra (The Scales) or Scorpius. This one will occur in Libra. Full moons occur when our natural satellite is opposite to the sun in the sky.

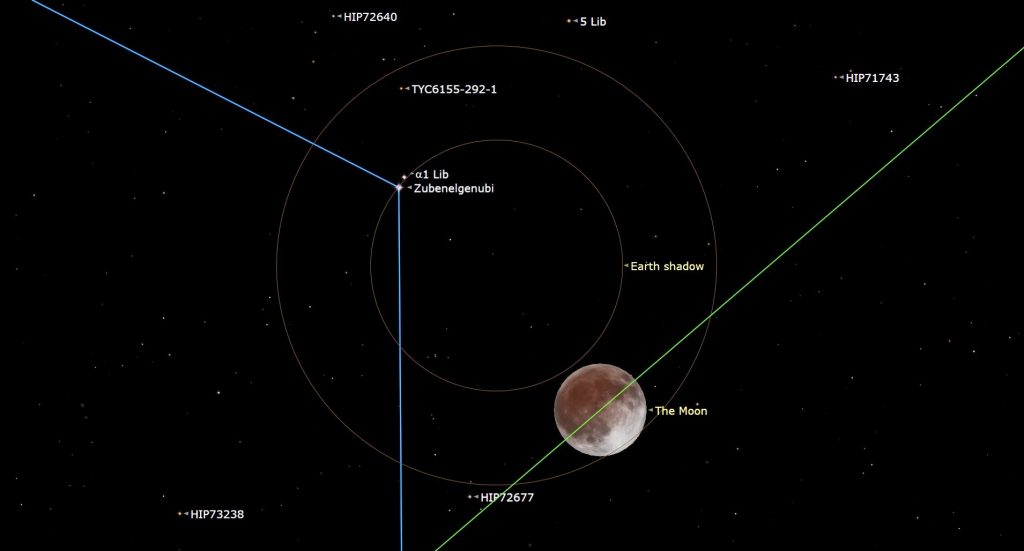

Friday’s full moon will pass through the Earth’s round penumbral shadow, very slightly dimming the northern part of the moon’s disk in a penumbral lunar eclipse. Observers in Asia, Southeast Asia, and Australia will see the moon begin to dip into the shadow at 15:13:39 GMT and then move clear of it at 19:31:54 GMT. At greatest eclipse at 17:24:04 GMT, 97% of the moon’s diameter will sit within the shadow. For much of Africa the moon will rise while partially eclipsed. Unfortunately, no part of this event will be visible in the Americas since the eclipse will be over before the moon rises. Online live streams will be showing the eclipse on Friday afternoon. By the way, Earth’s shadow on Friday evening will be centred a finger’s width below the bright star Zubenelgenubi in Libra. At the distance of the moon it’s only about two finger widths across, but it covers much more of the sky at the height of orbiting satellites. See if you notice an absence of satellites near Zubenelgenubi. Of course, Earth’s shadow will not attenuate the stars within it. Those are shining by their own light, and not by reflected sunlight.

The indigenous Ojibwe groups of the Great Lakes region call the May full moon Zaagibagaa-giizis, the “Budding Moon” or Namebine-giizis, the “Sucker Moon”. For them it signifies a time when Mother Earth again provides healing medicines. The Cree of North America call it Athikipisim, the “Frog Moon” – the time when frogs become active in ponds and swamps. The Cherokee call it Ahnisguti, the “Planting Moon”, when the fields are plowed and sown. Other common names are the Milk Moon, Flower Moon, or Corn Planting Moon.

When the still-bright, waning gibbous moon rises around 10 pm on Saturday evening, it will be positioned to the upper right of the bright, reddish star Antares in Scorpius (the Scorpion). Early risers on Sunday morning can see the moon with Antares above the southwestern horizon before dawn.

While the moon is 80% full or more this week, most of it will appear rather unimpressive in binoculars or your telescope. That’s because the sunlight will be shining straight-on to the eastern parts of the moon’s disk, and not casting any shadows from features there. The tones of white and grey we see at that time will only be produced by the various types of lunar surface rocks. The darkest areas are heavy basalt that leaked out of the moon and pooled within the broad shallow basins of the maria. The lighter areas are the original lunar crust. The brightest features of all are the freshest craters and the rays of ejected material that extend away from them. Last month here I wrote more about what to look for on a gibbous moon.

The Planets

Venus and Mars are the only planets we can see during evening this week.

Tonight (Sunday evening), the easterly orbital motion of the brilliant planet Venus will carry it between the two stars that mark the horns of Taurus (the Bull). While magnitude -4.17 Venus will start to appear in the lower third of the western sky soon after sunset, it will need to get a little darker before the horn stars appear. The right-hand, northern horn tip is marked by the bright star Elnath or Beta Tauri. That star, which also forms part of Auriga’s ringlike shape, will be binoculars-close to Venus – on the planet’s upper right. Once the sky becomes fully dark, one-third as bright Zeta Tauri, marking Taurus’ left-hand, southern horn tip star, will twinkle less than a binoculars’ field to Venus’ left (or celestial south-southeast).

Venus will set at about midnight this week. Viewed in a telescope, our sister planet will display a gibbous 65%-illuminated disk that is waning daily. To see its shape most clearly, wait until the sun has fully set and then aim your telescope at the planet while the sky is still bright. That way Venus will be higher and shining through less intervening air – and Venus’ glare will be lessened.

While you are waiting for Zeta Tauri to appear, look for the small, reddish dot of Mars. It will be positioned in central Gemini (the Twins), about halfway up the west-southwestern sky. The mis-matched “twin” stars Castor and Pollux will twinkle above Mars. The two bright, reddish stars Betelgeuse in Orion (the Hunter) and Aldebaran, the eye of Taurus, will shine below both Mars and Venus. Mars will continue to fade in brightness and become smaller in telescopes as Earth increases its distance from Mars. Like Venus, Mars will look best in a telescope while it’s perched on high – but it will look tiny under any magnification. Mars will set about an hour after midnight.

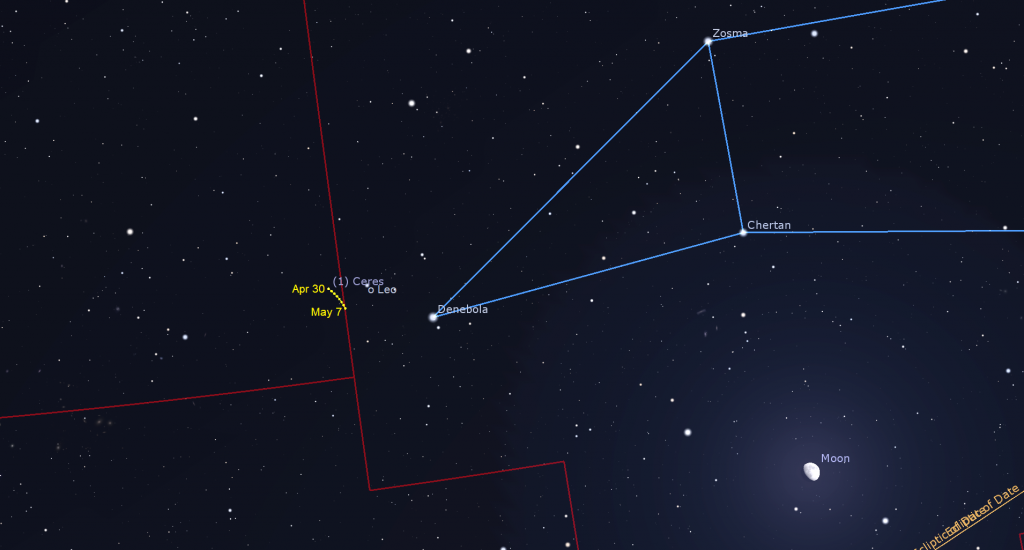

This week, Ceres, the largest object in the Main Asteroid Belt between Mars and Jupiter, will be located about two finger widths to the left (or 2.5° to the celestial ENE) of the very bright star Denebola, which marks the tail of Leo (the Lion). At magnitude 7.7 it’s bright enough to see in a backyard telescope or binoculars. To help you navigate to Ceres, a small star named Omicron Leonis, five times brighter than Ceres, will shine less than finger’s width to Ceres’ and Denebola’s right.

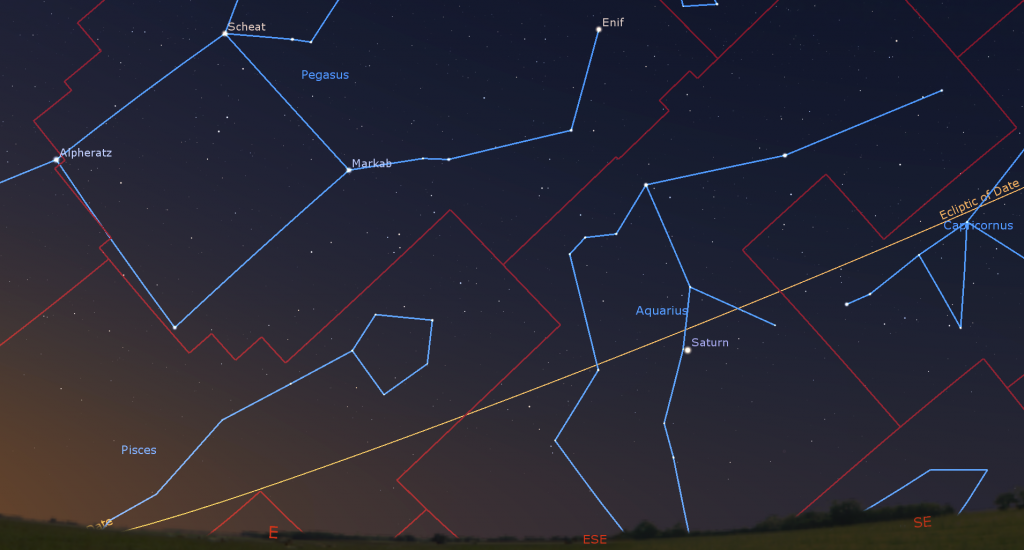

Finally, if you are up and outside between 5 and 5:30 am local time, and you have a clear view of the east-southeastern horizon, watch for the prominent yellowish dot of Saturn shining among the faint stars of Aquarius (the water-Bearer). Nothing else nearby will be as bright (except perhaps the space station). If the sky hasn’t brightened too much yet, look for the distinctive corner stars of the Great Square of Pegasus (the Flying Horse), over the eastern horizon well to the left of Saturn. The ringed planet will be rising 4 minutes earlier each day, so it will become visible at midnight around the end of June, and earlier in evening after that.

Delving into the Dippers

At this time of year, the Big Dipper is positioned high in the northern sky during mid-evening, stretched horizontally with its bowl facing downwards.

The Big Dipper is not a constellation – it’s an asterism! In the UK, they call this star pattern The Plough. The ancient Chinese, who also saw a dipper shape in those stars, used the orientation of the Big Dipper to mark the seasons. When it stood upright at dusk, spring was around the corner.

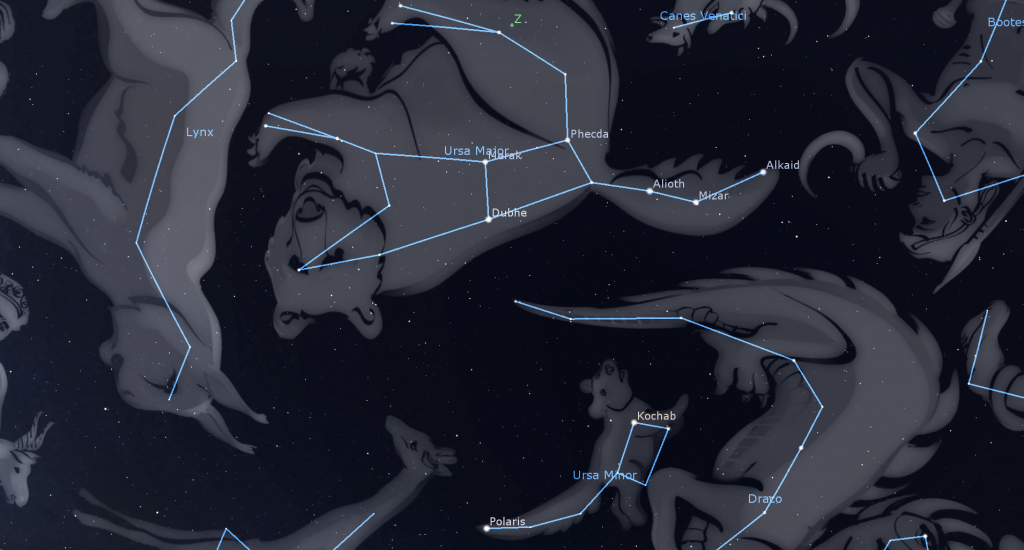

The dipper’s seven bright stars are only a portion of a large constellation called Ursa Major (the Big Bear). To see the bear standing upright, face south and crane your neck way back! Fainter stars located below and to the right (or celestial south and west) of the dipper’s bowl form the bear’s head and neck, and its front and rear legs. The bowl of the dipper looks a bit like a saddle on the bear’s back. The dipper’s handle doubles as the bear’s tail. But, wait a minute – real bears have stubby tails! Well, legends say the bear was swung into the night sky by its tail – thus stretching it!

You can use the Big Dipper to practice measuring the sky. Astronomers describe how far apart two objects in the sky are by measuring the angle between them, or their angular separation. Since the sky is a giant bowl, all the measurements are portions (or arcs) of a circle. There are 360 degrees ( ° ) in a circle and therefore 180 degrees in half the sky (horizon to horizon). If you point at two different objects at the same time, the angle between your straight arms is their angular separation.

For close-together objects or deep sky clusters, nebulas, and galaxies, we divide one degree into sixty arc-minutes ( ‘ ), and then each arc-minute into sixty arc-seconds ( “ ). The full moon is 32 arc-minutes across, and planets’ disk sizes are given in arc-seconds. The larger and brighter spring galaxies are several arc-minutes in size.

On early May evenings, the rightmost two stars in the dipper mark the outer rim of its bowl. Dubhe “doo-bee”, the higher of the two, is a medium-hot, orange giant star located about 124 light-years from Earth. Hot, white Merak below it is only 80 light-years from Earth. In the sky, those two stars are separated by 5.3°. Stretch your hand out in front of you and compare their separation to your palm’s width or various finger combinations. For most people, that’s three or four finger widths (with your hand at arm’s length). The name Dubhe is a shortened form of an Arabic expression that means “Back of the Greater Bear”, while Merak means “the Flank of the Greater Bear”.

Moving to the left (celestial east), the star where the handle meets the bowl is named Megrez, which comes from “the Root of the Greater Bear’s tail”. This star is the dimmest of the seven. It’s a medium-hot, white star located 81 light-years from the sun. The star at the lower left corner of the bowl is Phecda, from “Thigh of the Greater Bear”. (Hmm – I think there’s a pattern here.) It, too, is a white star located about 80 light-years away. The width across the bowl’s rim is 10°, or about your clenched fist’s width.

Astronomers believe that five of the stars in the dipper formed together about 300 million years ago, and are still travelling through space together as siblings – hence their similar distances from Earth. The three stars in the dipper’s handle (from right to left) are Alioth, Mizar, and Alkaid. Alioth is another of the “bowl star siblings”. Alkaid is a slightly cooler, warmer coloured star located 104 light-years from Earth.

Mizar, the hot, white star at the bend in the dipper’s handle, has a dim companion star named Alcor sitting just to the upper left (or northeast) of it. Most people can see little Alcor without assistance. In ancient times, it was used to judge the eyesight of soldiers. In some cultures, Mizar and Alcor are called “The Horse and Rider”. In a small telescope, Mizar separates into a lovely double star with Alcor shining brightly a short distance from them. The length of the dipper from Alkaid, at the handle-tip, to Dubhe, at the far rim, is 26°. Most people can span this with a surfer’s salute – your outstretched thumb-tip to your pinky fingertip. Try it! I’ll post a sky-measurements diagram here.

Now turn and face north again. If you draw an imaginary line from Merak though Dubhe and extend it downward (or celestial north), the next major star you’ll encounter is Polaris, the North Star. Using your new sky-angle-measuring skill, you should come up with a 29° span from Dubhe to Polaris.

Polaris marks the tip of the handle of the Little Dipper. At this time of year at around 10 pm local time, the rest of the Little Dipper curves upwards to the right from Polaris, towards the Big Dipper. The two bowls pour into one another. The tail stars of the large constellation Draco (the Dragon) detours around the Little Dipper and ends between the dippers’ bowls.

The asterism of the Little Dipper also makes up the constellation of Ursa Minor (the Little Bear). This little cub’s tail is stretched even longer than its larger parent. Other cultures have interpreted those stars as a dog or a wolf, which explains the lengthy tail much better! The indigenous Ojibwe people see the Big Dipper stars as Ojiig, the Fisher, which is a weasel-like animal. The Little Dipper is Maang, the Loon. They tell a wonderful story about the way those animals saved the world!

The star at the outer edge of the Little Dipper’s bowl (and closest to the Big Dipper) is slightly dimmer than Polaris. This medium-cool, reddish star is named Kochab. The other five stars of the constellation may be too dim to see from the city, but binoculars will reveal them.

Polaris is located about one finger’s width away from the north celestial pole – the point in space directly above the North Pole on Earth. As Earth rotates on its axis, all the stars rotate counter-clockwise (west to east) around Polaris. Polaris’ fixed location makes it especially useful for navigation – at least from the northern hemisphere, where it never sets. The point on the horizon directly below it is due north, and the star’s angle above the horizon gives you your latitude. Measure it!

Contrary to popular belief, Polaris is a very modest looking star. It’s only 48th brightest in the night sky. Viewed through binoculars or a small telescope, Polaris appears as the diamond in a crooked ring of dim stars. Coincidentally, the ring is one finger width across!

Eta-Aquariids Meteor Shower

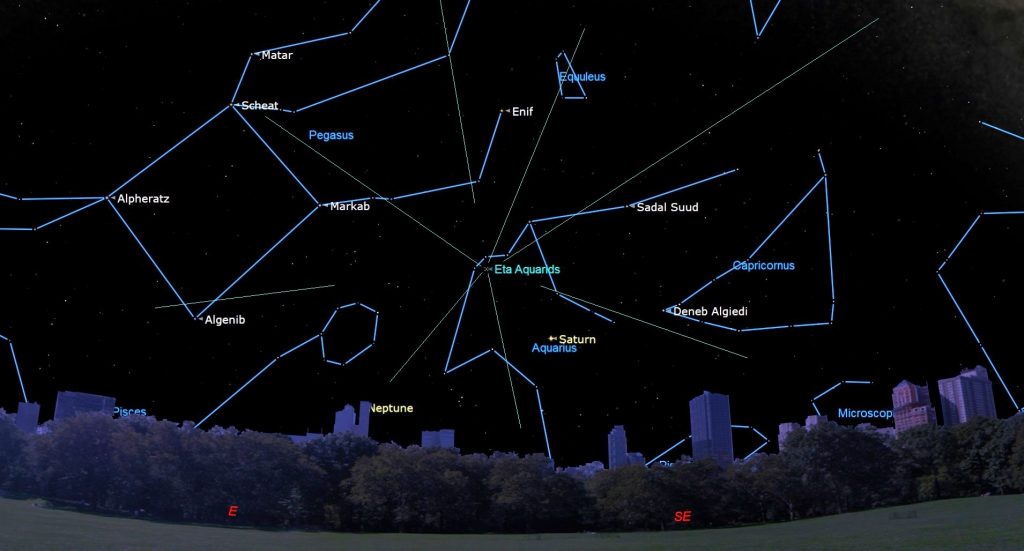

The annual Eta-Aquariids Meteor Shower is produced when Earth travels through a cloud of particles of material left behind by repeated passages of Halley’s Comet. Those particles drop through our atmosphere at high speeds, producing the long streaks of ionized air and burning up minerals we see as “shooting stars”. While we pass through the debris from May 3 to 11 annually, Earth will travel through the densest part of the cloud on Saturday afternoon, May 6 in the Americas.

Since viewing meteors requires a dark sky, watch for the Eta-Aquariids before dawn on Saturday morning and then again on Saturday evening. Expect to see some fireball meteors, too – but less than the few dozen meteors per hour that are typical during the peak.

A nearly full moon will lessen the show this year, but it will sink low before dawn on Saturday. True Eta-Aquariids meteors will appear to be travelling away from a radiant point in the night sky near the constellation of Aquarius (the Water-Bearer), which will rise above the southeastern horizon around 2:30 am local time. Its southerly radiant makes the Eta-Aquariids shower better for observers located closer to the tropics.

To increase your chances of seeing meteors during any shower, find a dark location with lots of sky, preferably away from light polluted skies, and just look up with your unaided eyes. Binoculars and telescopes are not useful for meteor-watching because their fields of view are too narrow to catch the long streaks of meteor light. Don’t watch the radiant since any meteors near there will have very short trails because they are travelling towards you. Try not to look at your phone’s bright screen – it’ll ruin your night vision. And keep your eyes heavenward, even while you are chatting with companions. Good luck!

Public Astro-Themed Events

Every Monday evening, York University’s Allan I. Carswell Observatory runs an online star party – broadcasting views from four telescopes/cameras (weather permitting), answering viewer questions, and taking requests! Details are here. They host in-person viewing on the first clear Wednesday night each month. On Wednesdays they stream views online via the observatory YouTube channel. Details are here.

On Wednesday evening, May 3 at 7:30 pm EDT, the RASC Toronto Centre will host their in-person monthly Recreational Astronomy Night Meeting in the Gemini East Room at the Ontario Science Centre. The meeting will also be live streamed at https://www.youtube.com/rasctoronto/live. Talks include The Sky This Month, red giant stars, and making your own telescope. Details are here.

On Thursday, May 4, starting at 8 pm, U of T’s AstroTour will present a free public lecture entitled Mapping our universe in millimeter: what have we learned? The speaker will be Dr. Yilun Guan, a postdoctoral fellow at the Dunlap Institute of Astrophysics and Astronomy, University of Toronto. The talk will be followed by astronomy demos and telescope tours (weather permitting). Details are here.

On Friday, May 5 from 9:30 to 11:30 pm EDT, RASC Toronto will host Family Night at the David Dunlap Observatory for guests aged 7 and up, who will tour the sky, visit the giant 74” telescope, and view celestial sights through telescopes if the sky is clear. This program runs rain or shine. Details are here, and the link for tickets is here.

On Sunday afternoon, May 7 from 12:30 to 1 pm EDT, head to the David Dunlap Observatory for in-person DDO Sunday Sungazing. Safely observe the sun with RASC Toronto astronomers! During the session, which is for ages 7 and up, a DDO Astronomer will answer your questions about our closest star – the sun! Registrants will be given an eclipse viewer, learn how the sun works and how it affects our home planet, view the sun through solar telescopes, weather permitting, and visit the giant 74” telescope. More information is here and the registration link is here.

My free, family-friendly Insider’s Guide to the Galaxy webcast with RASC National returns on Tuesday, May 11 at 3:30 pm EST. Panelists will talk about ways to encourage and support girls and young women to take up astronomy. Then we’ll highlight our next batch of spring RASC Finest NGC objects. You can find more details and the schedule of future sessions here.

Keep looking up, and enjoy the sky when you do. I love questions and requests. Send me some!