Monday’s New Moon Brings Diwali and a Partial Eclipse, Arcturus Ghosts the Sun, and Jupiter’s Moons Say Boo!

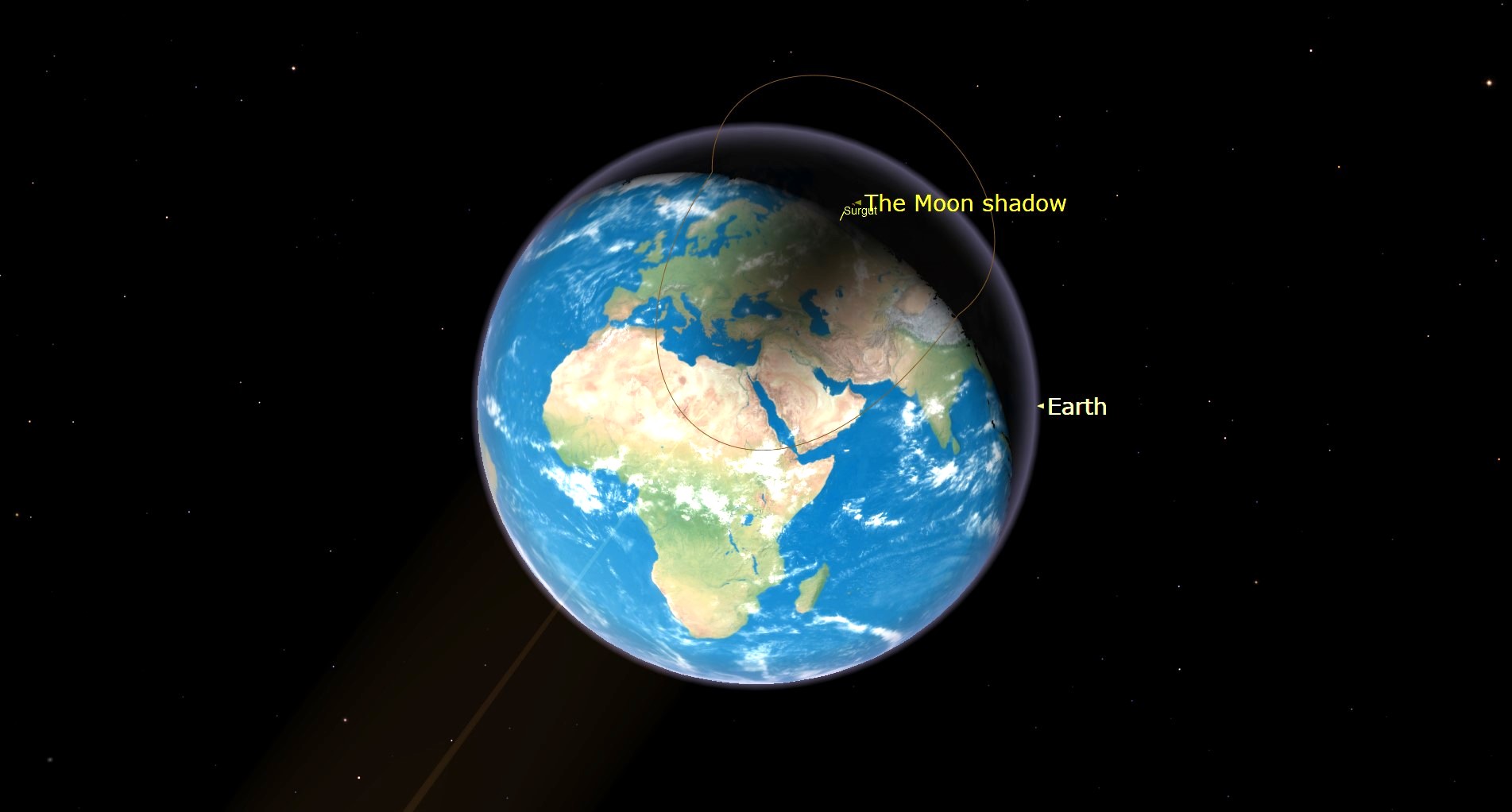

The circumstances for Tuesday’s partial solar eclipse, which will occur during the new moon syzygy. The eclipse will only be visible with protective solar filters across parts of Europe, Africa, and Asia. This scene shows the position of the moon’s shadow on Earth at 11:01 GMT on October 25, 2022. (Starry Night)

Hello, Late-October Stargazers!

Here are your Astronomy Skylights for the week of October 23rd, 2022 by Chris Vaughan. Feel free to pass this along to your friends and send me your comments, questions, and suggested topics. You can also follow me on Twitter as @astrogeoguy! Unless otherwise noted, all times are expressed in Eastern Time. To subscribe to these emails please click this MailChimp link.

If you’d like me to bring my Digital Starlab portable inflatable planetarium to your school or other daytime or evening event, or deliver a session online, contact me through AstroGeo.ca, and we’ll tour the Universe, or the Earth’s interior, together! My terrific book with John A. Read entitled 110 Things to See With a Telescope is a guide to viewing the deep sky objects in the Messier List – for both beginners and seasoned astronomers. DM me to order a signed copy!

The Moon will pass new, bringing Diwali and a partial solar eclipse for Asia on Monday. Then it will gradually return to view in the western post-sunset sky. Three bright planets Saturn, Jupiter, and Mars will parade during evening – with Saturn’s moon Iapetus looking brighter, two of Jupiter’s moons popping out of its shadow, and Mars brightening. Arcturus is the ghost of summer and the zodiacal light appears in morning. Read on for your Skylights!

Happy Diwali!

Like many traditional observances around the world, the timing of the South Asian festival of Diwali, or the Festival of Lights, has an astronomical connection. It lasts five days, always beginning just before the new moon phase that falls between mid-October and mid-November – dubbed “the darkest night of the year”. In 2022, Diwali will commence on Monday, October 24, just hours before Tuesday’s new moon. Expect to hear some fireworks, or to see some colourful lights from celebrants!

Diwali celebrates the triumph of good over evil after the fall harvest. The festival’s name arises from the Sanskrit expression deepa avali, or “rows of lighted clay lamps” – which were set outside when there was no moon to light the way at night.

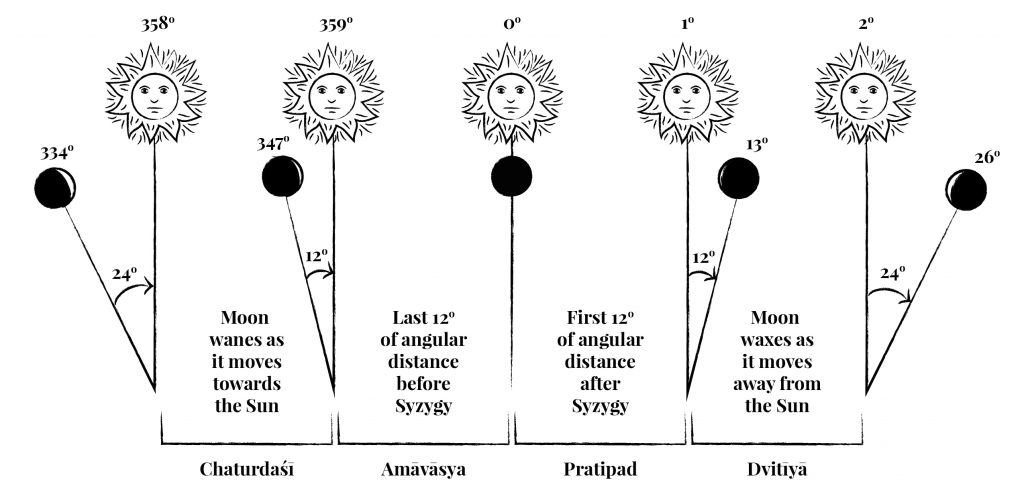

The Hindu lunisolar calendar employs twelve 30-day months within a 360-day year. To avoid calendar drift caused by its annual five day shortfall, it adds an extra (intercalary) month every two or three years, in a pattern that repeats every 19 years. Months commence at the full moon, and are followed by a “bright” fortnight. Each mid-month’s new moon kicks off a “dark” fortnight. The Hindu new year begins around the March equinox. The Hindu month that commences around mid-October on the Gregorian calendar is named Kartik or Kartika.

During its orbit around Earth, the moon varies its angle from the sun by about 12 degrees per day, resulting in 30 unique phases, half of them waxing and the other half waning. Each day of the Hindu lunar month is called a tithi, with each tithi bearing a name associated with a particular illuminated phase. On the day before new moon (or syzygy), the moon is less than 12 degrees west of the sun, and appears as a slim waning crescent. That tithi is called Amāvásyā (Sanskrit: अमावस्या), which literally translates to “no moon there”, since it’s rarely observable. The tithi for the day following new moon (slim waxing crescent) is Pratipada. Diwali always commences on Amāvásyā, the 15th day of Kartika.

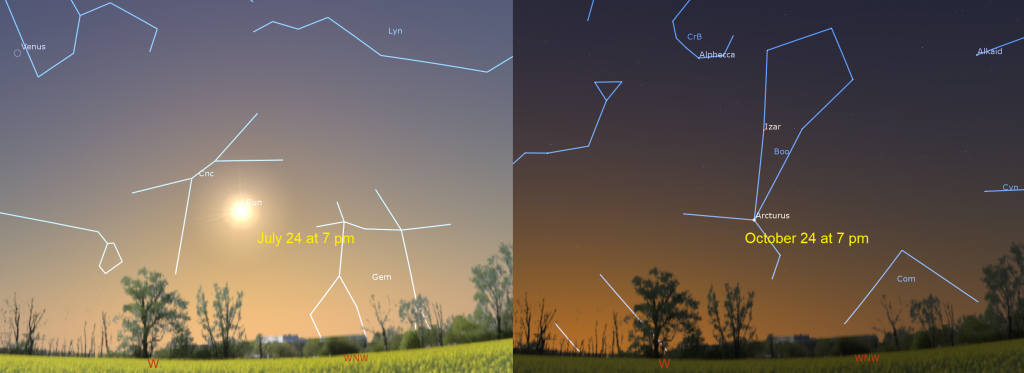

Ghost of the Summer Sun

During the week before Halloween, especially Oct 25, the bright star Arcturus becomes “the Ghost of the Summer Sun”! That’s because its sits at about the same altitude and azimuth in the sky that the sun did exactly four months earlier at the same time of the evening – in broad daylight, though.

Morning Zodiacal Light for Mid-Northern Observers

During autumn at mid-northern latitudes every year, the ecliptic extends nearly vertically upward from the eastern horizon before dawn. That geometry favors the appearance of the faint zodiacal light in the eastern sky for about half an hour before dawn on moonless mornings. Zodiacal light is sunlight scattered by interplanetary particles that are concentrated in the plane of the solar system – the same type of material that produces meteor showers. It is more readily seen in areas free of urban light pollution. For observers at low latitudes, the ecliptic is nearly vertical all year round, making the light a frequent phenomenon. Sadly, observers north of 60°N latitude miss out.

If your location favours it, between now and the full moon on November 8, look for a broad wedge of faint light extending upwards from the eastern horizon and centered on the ecliptic. It will be strongest in the lower third of the sky, below the bright star Regulus. Try taking a long exposure photograph to capture it. Don’t confuse the zodiacal light with the Milky Way, which is positioned nearby in the southeastern sky.

Comet E3 Update

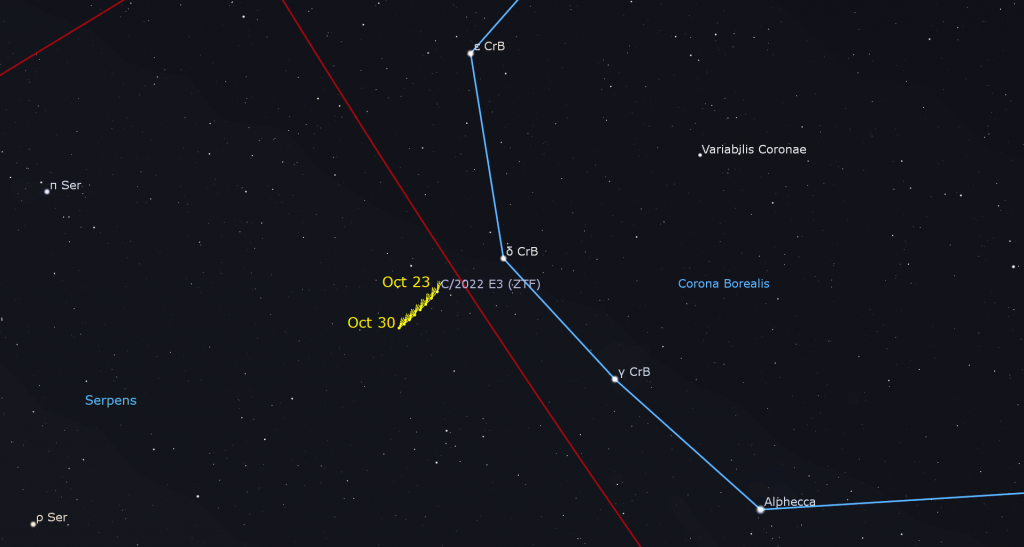

For several weeks, I’ve been sharing updates on a comet named c/2022 E3 (ZTF) that is predicted to become bright enough to see in binoculars next February. For now, it is still very far away, but it is visible in 8” or larger telescopes during early evening. I saw it on Friday through my large, 12.5” aperture telescope while at a reasonably dark sky location. The comet’s faint fuzzy patch wasn’t a very impressive sight, though.

This week comet E3 ZTF will continue its slow trip through the northern reaches of Serpens (the snake) where that constellation borders the left-hand (or southeastern) edge of the constellation of Corona Borealis (the Northern Crown). Those stars occupy the lower third of the western sky after dusk. The keystone shape of Hercules is positioned above the crown of stars. The very bright star Arcturus will sparkle below them after dusk. At latitudes near Toronto, Corona Borealis’ stars should become visible to your unaided eyes by 7:30 pm in your local time zone. The constellation won’t set until nearly 11 pm, but there won’t be much point in trying for the comet after about 8:45 pm. You’ll be looking through too much intervening air.

Tonight (Sunday) the comet will sit less than a finger’s width to the lower right (or 0.6 degrees to the celestial south) of the medium-bright star named Delta Coronae Borealis. The comet will shift a little farther from the star each night. By next Sunday night it will be positioned more than a finger’s width to the lower left (or celestial south) of Delta. All week long, the comet and that star will remain cosy enough to share the view in a telescope.

The comet will remain near the boundary between Corona Borealis and Serpens (the Snake) for the next two months, but those stars will soon be overwhelmed by the evening twilight – so make your attempts to see the comet sooner than later.

The Moon

After going missing from evening skies worldwide for the past week, the moon will return to view this week – but not until it finishes some business!

Early risers on Monday morning might be able to spot the extremely slim crescent moon, only 1%-illuminated, shining over the eastern horizon. As a bonus, the moon will shine less than a thumb’s width above (or 1.6 degrees to the northwest of) the bright dot of planet Mercury. The duo will be tough to see within the pre-dawn twilight. Binoculars will help your search – but be sure to turn them away before the sun rises. The moon will actually pass in front of, or occult, Mercury on Monday between 10:15 am EDT and 11:21 am EDT – but that will happen in a daytime sky for much of the Americas, so it’s not safe to observe by non-experts.

The moon will officially reach its new moon phase at 6:49 am EDT, 3:49 am PDT, or 10:49 Greenwich Mean Time on Tuesday, October 25. This new moon will also feature a deep partial solar eclipse that will be visible across most of Europe, northeastern Africa, the Middle East, and central Asia. After the moon’s penumbral shadow first contacts Earth in the North Atlantic Ocean around sunrise at 08:58:20 GMT, it will sweep eastward and south across Europe and the Middle East until it lifts off the Earth near the Persian Gulf at 13:02:16 GMT, ending the eclipse. The instant of greatest eclipse, with the moon blocking 0.63 of the sun’s diameter, will occur east of Surgut, Russia, around sunset, at 11:01:20 GMT. You can find detailed information about this eclipse at Fred Espenak’s Eclipsewise website here. Protective solar filters will be needed to view any part of this eclipse in person. Several groups will live stream the eclipse online, including Timeanddate.com here. This solar eclipse will be followed by a total lunar eclipse visible in the Americas on November 8.

The young crescent moon will return to visibility just above the west-southwestern horizon after sunset on Wednesday. As the moon increases its angle from the sun each day, it will become easier to see – waxing to a thicker crescent and setting about 35 minutes later each evening. Thursday’s pretty moon will shine among the stars of Scorpius (the Scorpion). You might catch a glimpse of the scorpion’s brightest star Antares twinkling to the moon’s left – but only observers living at southerly latitudes will easily see Scorpius’ stars before moonset.

The moon will definitely be lingering long enough to shine among some stars from Friday onward. It will trip over Ophiuchus, the Serpent-Bearer’s foot on Friday and then spend the coming weekend traversing the teapot-shaped stars of Sagittarius (the Archer). That weekend will kick off the best viewing period for the moon in binoculars and backyard telescopes. More about that next week.

The Planets

If you don’t catch sight of Mercury when it poses with the crescent moon above the eastern horizon before sunrise on Monday morning, or see it shining alone there on Tuesday, you won’t see either of the two inner planets until Mercury and Venus both emerge from the western post-sunset glow a month from now. But that’s okay – three bright planets are parading the evening sky!

After dusk, look in the lower third of the southeastern sky to see the yellowish, medium-bright dot of magnitude 0.62 Saturn shining amidst the faint stars of Capricornus (the Sea-Goat). Yesterday (Saturday night), Saturn’s westerly motion through the stars ceased as it completed a retrograde loop that it began in early June. For the next several nights, Saturn will shine half a finger’s width to the left (or 0.6 degrees to the celestial east-northeast) of a medium-bright star named Iota Capricorni. That’s close enough to share the view in binoculars and a backyard telescope. When Saturn resumes its regular easterly prograde motion in the coming weeks, it will widen its separation east of that star. Retrograde loops by the outer planets occur when Earth, on a faster orbit closer to the sun, passes them on the “inside track”, making them appear to slide west for a while.

Planets look clearest in telescopes when they are higher in the sky. At that time, you are viewing them through less intervening, turbulent air than when they are low. Plain old turbulence in the air overhead can also mar our views even when objects are high in the sky. (On nights like that, the stars twinkle more.) To best see a planet’s features, take long looks and wait for moments of perfect clarity. This week, Saturn will be highest in the south by 8:30 pm local time. The views of it will degrade until it sets in the west after midnight.

Very good binoculars should show Saturn and its rings as a tiny oval. On a good night, even a small telescope can show Saturn’s subtly banded globe encircled by its glorious rings, which are sufficiently edge-on to us to allow Saturn’s southern polar region to extend well beyond the ring plane. See if you can make out the Cassini Division, a narrow, dark zone that separates Saturn’s main inner ring (named B) from its bright outer ring (named A). Saturn’s position west of the anti-solar point has caused the planet’s globe to cast a widening wedge of dark shadow onto the rings where they emerge from behind the eastern limb of the planet. Where you see that shadow will depend upon how your telescope flips and/or mirrors the view. In a refractor or SCT telescope, it’s toward the upper right. In a Newtonian reflector, it will be toward lower right. An equatorial mount will rotate the scene, too.

A small telescope can also show several of Saturn’s moons – especially its largest, brightest moon, Titan! From here on Earth, Saturn’s axial tilt of 26.7° lets us see the top of its ring plane, and allows its brighter moons to array themselves all around the planet. Titan never wanders more than five times the width of Saturn’s rings from the planet. The much fainter moon named Iapetus can stray up to twelve times the rings’ width during its 80-day orbit of Saturn. Iapetus has one dark hemisphere and one bright hemisphere. This week, that moon will appear while its lighter half faces our direction.

The next brightest moons Rhea, Dione, Tethys, Enceladus, and Mimas all stay within one ring-width of Saturn. During evening this week, Titan will migrate counter-clockwise around Saturn, moving from above (or celestial north of) the planet tonight (Sunday) to the lower left (or celestial southeast) of Saturn next Sunday. (Remember that your telescope might flip that view around.) How many of the moons can you see in your telescope?

Once you’ve spotted Saturn turn your gaze about four fist widths to the right to see 24 times brighter, magnitude -2.85 Jupiter. Jupiter will climb highest in the sky (or culminate over southern horizon) at around 11 pm local time. The extremely bright planet will cross the sky all night long and then set in the west around 5 am local time. Any decent pair of binoculars will show Jupiter as a small disk flanked by its string of four Galilean moons named Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto. They complete orbits of the planet every 1.7, 3.6, 7.2, and 16.7 days, respectively. If you see fewer than four moons, then one or more of them is crossing in front of or behind Jupiter or lurking in Jupiter’s dark shadow – or two of the moons are occulting one another. Their arrangement varies each night.

A pentagon of stars sits about a fist’s diameter above Jupiter. They represent the western head of Pisces (the Fishes). All five should almost fit within your binoculars’ field of view. The brightest two stars are on the left and right. The stars in the ring shine at about the magnitude limit that you can see without aid under suburban skies. How many can you see? The rest of Pisces forms a huge V of faint stars extending downward to Jupiter’s left (or celestial east).

Any size of telescope can show Jupiter’s dark belts and light bands, which are aligned parallel to its equator. Because Jupiter rotates once every 10 Earth-hours, anyone can use a good backyard telescope to watch the pink, pale Great Red Spot crossing the planet for 3 hours on every 2nd or 3rd night. For observers in the Americas, that GRS will cross Jupiter’s disk in early evening on Tuesday, Thursday, and Sunday, late on Monday and Saturday evening, and during the wee hours of Thursday and Saturday. If you have any coloured filters or nebula filters for your telescope, try enhancing the GRS with them.

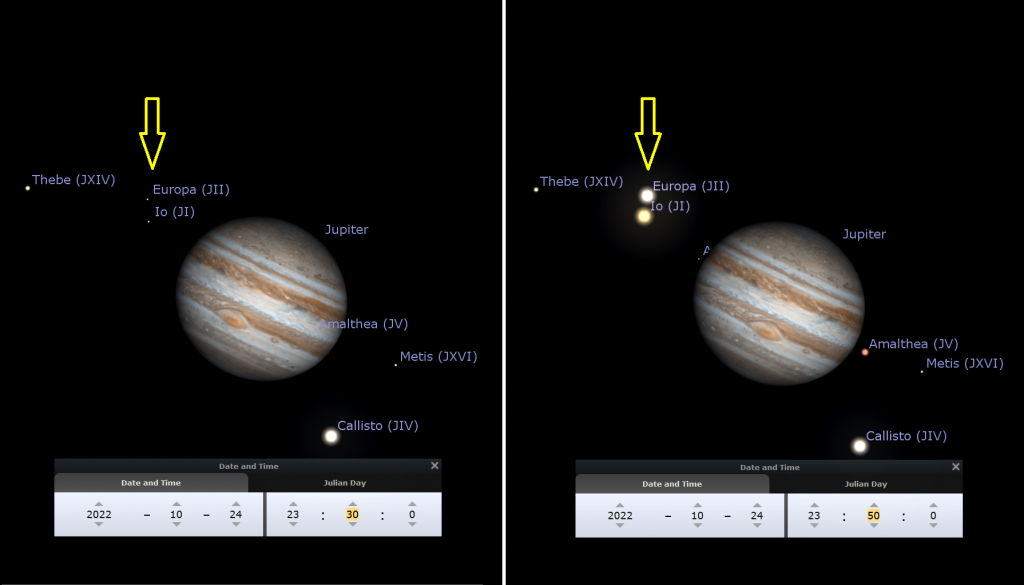

Jupiter’s moons pass in and out of the great planet’s shadow. On Monday night, October 24 at 11:33 pm and 11:48 pm EDT, respectively, Io and then Europa will pop into view as their orbits lift them out of Jupiter’s shadow. Use any size of telescope, and start to watch several minutes ahead of time. Before the two moons appear, the bright speck of Callisto will be visible near Jupiter. The duo will appear near one another, but on the other side of Jupiter from Callisto. The Great Red Spot will be mid-planet, too! Good luck!

The small, black shadows of Jupiter’s Galilean moons are visible through a good backyard telescope when they cross the planet’s disk. For observers in the America’s, Io’s shadow will cross Jupiter’s equator on Monday morning, October 24 between 12:05 am and 2:15 am EDT. Io’s shadow will cross again, with the Great Red Spot, on Tuesday evening from 6:35 to 8:45 pm EDT. Don’t forget to adjust these quoted times into your own time zone. On Wednesday evening, October 26 observers with telescopes across Africa, Europe, and western Asia can watch the shadows of two of Jupiter’s moons cross the southern hemisphere of the giant planet together for two hours. At 10:20 pm CEST or 20:20 GMT, the large shadow of Ganymede will join Europa’s smaller shadow, which began to cross at 9:55 pm CEST. Europa’s shadow will move off Jupiter at 12:20 am CEST or 22:20 GMT, leaving Ganymede’s shadow to cross alone until 1 am CEST or 23:00 GMT.

Mars is getting truly bright and larger now! This week, the very red-looking, magnitude -1.0 planet will rise over the east-northeastern horizon by 10 pm local time and then cross the sky all night. Watch for the bright Pleiades star cluster shining to Mars’ upper right, and the bright, goat-star star Capella with its three little “kids” shining to Mars’ upper left (or celestial north). Mars will climb highest, in the south, before 5 am. I know that’s too early for some – but that time will advance by half an hour each week.

On Saturday night, October 29 in the Americas, Mars’ eastward prograde motion through the stars of Taurus (the Bull) will slow to a stop in order for it to begin a westerly retrograde loop that will last through its December opposition and into mid-January. All this week, Mars will be positioned between the two horn tips of the bull, the medium-bright stars Zeta Tauri and Elnath (Beta Tauri). Over the next month, you can watch Mars swing between those stars and then race west towards the Pleiades.

Viewed in a telescope this week, Mars will show a waxing, 92%-illuminated disk, with some of the dark markings that will sharpen up as Earth’s faster orbit draws us closer to the red planet over the coming weeks. We’re 98 million km (or 5.5 light-minutes) away from it this week.

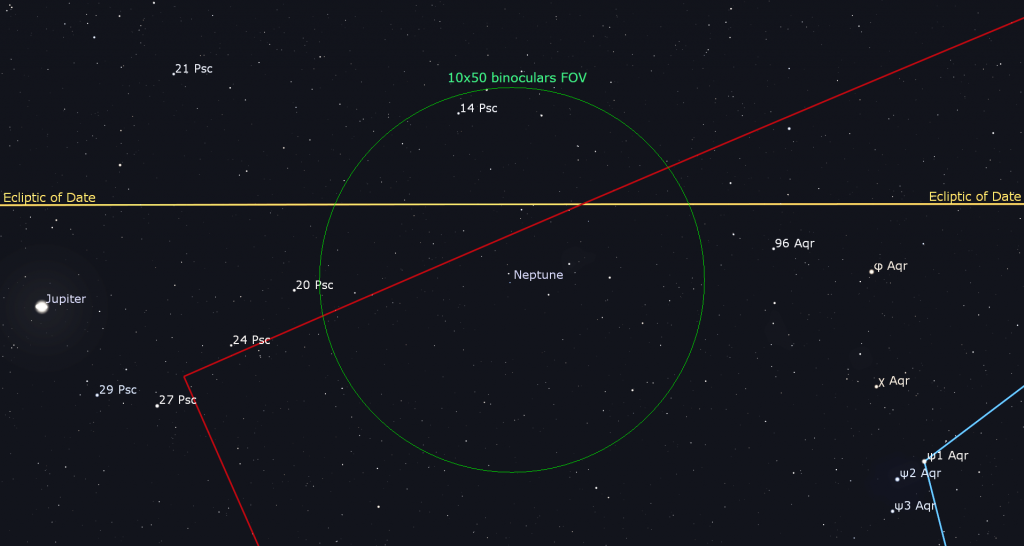

There are several fainter planets and asteroids lurking between the bright ones. Magnitude 7.8 Neptune is located 0.7 fist widths to the right (or 7° to the celestial west-southwest) of Jupiter, which will slide a wee bit closer to the distant planet every night. Neptune’s apparent disk size is 2.4 arc-seconds (20 times smaller than Jupiter’s). Try for Neptune while it is highest in late evening.

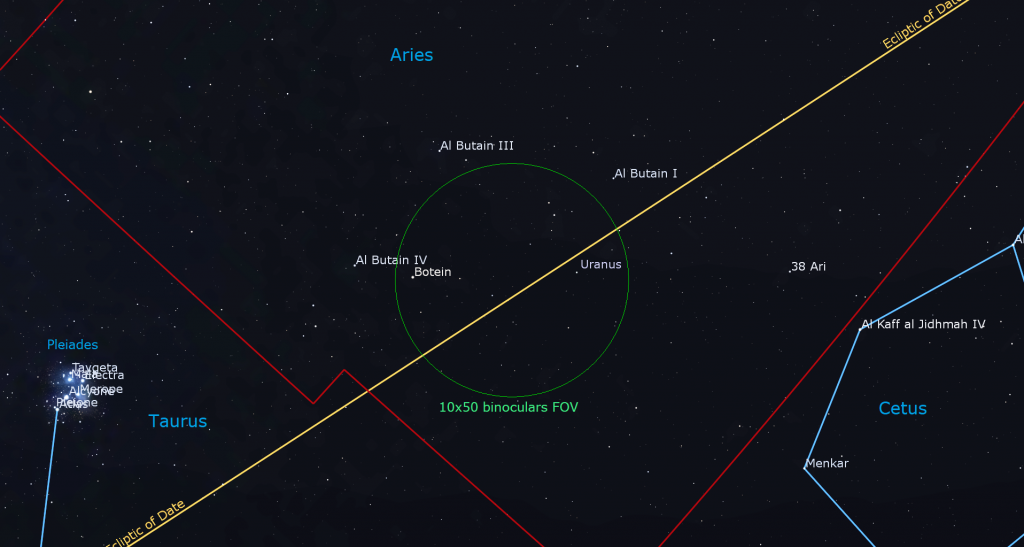

Uranus is located between Mars and Jupiter, and about 1.3 fist widths to the upper right (or 13° to the celestial west-southwest) of the Pleiades star cluster. Closer guideposts to Uranus are several medium-bright stars named Botein (or Delta Arietis), Al Butain II (or Rho Arietis), and Sigma Arietis which will appear several finger widths from Uranus. Those stars mark the feet of the Aries (the Ram). The magnitude 5.7 planet will be high enough for telescope-viewing, in the lower part of the eastern sky, by 9 pm local time this week.

Dark Nights Delights

If you missed last week’s suggestions for deep sky objects that are bright enough to see in binoculars this week, even in mildly light-polluted skies, you can read it here.

Public Astro-Themed Events

Every Monday evening, York University’s Allan I. Carswell Observatory runs an online star party – broadcasting views from four telescopes/cameras, answering viewer questions, and taking requests! Details are here. They host in-person viewing on the first clear Wednesday night each month. Other Wednesdays they stream views online via the observatory YouTube channel. Details are here.

My free, family-friendly Insider’s Guide to the Galaxy webcasts with Samantha Jewett of RASC National returns on Tuesday, October 25 at 3:30 pm EDT. Recently, the team behind Stellarium has made major improvements to the mobile app version of the software, making it comparable to the gold standard SkySafari app. We’ll work through the basic functions and the advanced features available in Stellarium Plus, including Satellite tracking, telescope/eyepiece simulated views, and observing planning. We’ll highlight some news for Stellarium desktop users, too. You can find more details and the schedule of future sessions here.

On Tuesday evening, October 25 at 7:30 pm EDT, the Perimeter Institute in Waterloo will present a free public talk and webcast by dark matter researchers Dr. Katie Mack, Hawking Chair in Cosmology and Science Communication at the Perimeter Institute, and Ken Clark, an associate professor at the Arthur B. McDonald Canadian Astroparticle Physics Research Institute. They will share insights into the ubiquitous, mysterious matter that makes up the majority of stuff in our universe. Registration and details are here.

On Friday evening, October 28 at 7:30 pm EDT, the RASC Mississauga Centre will live stream their free, public monthly Speakers Night meeting. This month will feature Prof. John Percy, an active Professor Emeritus in Astronomy & Astrophysics, and in Science Education at the Ontario Institute for Studies in Education (OISE-UT). His talk is titled Misconceptions about the Universe: From Everyday Life to the Big Bang. Everyone is invited to watch the presentation live on Zoom. Details are here.

Keep looking up, and enjoy the sky when you do. I love questions and requests. Send me some!