Moon Months, Maximum Mercury near Venus, and Meteors Mount as the Moon Moves to Morning!

This image of Saturn through the 20″ diameter telescope at the Weikersheim Observatory in southern Germany just after it emerged from behind the moon was the NASA APOD for April 7, 2013. It was composited together from two different exposures by Jens Hackmann.

Hi, Summer Stargazers!

Here are your Astronomy Skylights for the week of July 21st, 2024 by Chris Vaughan. Feel free to pass this along to your friends and send me your comments, questions, and suggested topics. You can also follow me on Twitter as @astrogeoguy! Unless otherwise noted, all times are expressed in Eastern Time. To subscribe to these emails please click this MailChimp link.

If you’d like me to bring my Digital Starlab portable inflatable planetarium to your school or other daytime or evening event in Simcoe, Grey, and Bruce Counties, or deliver a virtual session anywhere, contact me through AstroGeo.ca, and we’ll tour the Universe, or the Earth’s interior, together! My book with John A. Read entitled 110 Things to See With a Telescope is a guide to viewing the deep sky objects in the Messier List – for both beginners and seasoned astronomers. DM me to order a signed copy!

The moon will move out of the night sky and into morning as it wanes from full to third quarter on Saturday, posing with, and passing in front of, Saturn for parts of the world. The bright moon’s departure will give back the summer Milky Way to stargazers. Expect to see a few meteors while you are out and about on clear nights. The inner planets will linger for a short time in the west after sunset. The rest of the planets will gleam in the east before dawn. Read on for your Skylights!

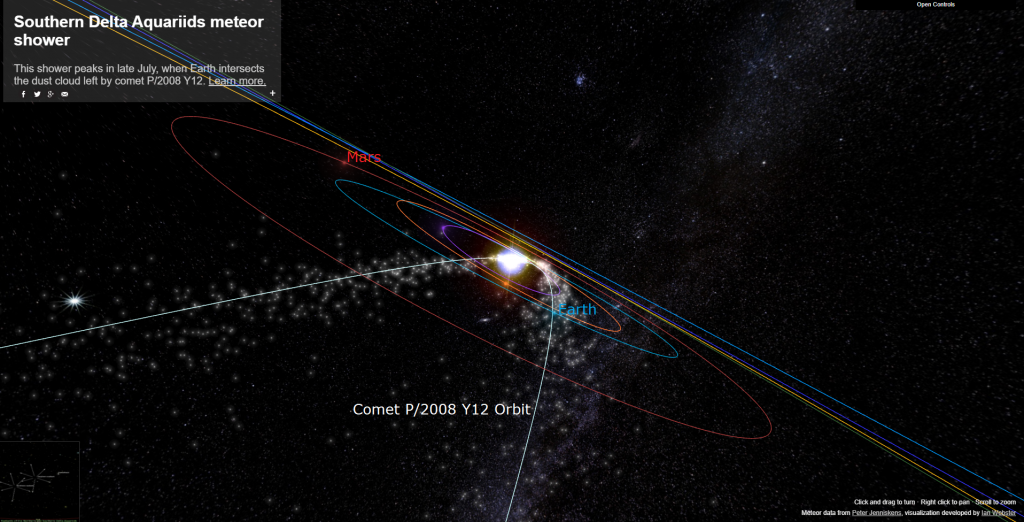

Southern Delta Aquariids Meteor Shower

The annual Southern Delta Aquariids meteor shower, which runs from July 18 to August 21, is caused when the Earth passes through a cloud of tiny particles dropped by a periodic comet – likely Comet P/2008 Y12 (SOHO). The shower will peak overnight next Sunday, July 28-29, but is especially active for a week surrounding that date, so you can keep an eye out for meteors all this week. The prolific Perseids meteor shower, which runs annually between July 17 and August 26, has begun, too! That shower will peak on August 11-12.

Moons and Months

The word “month” resembles “moon” because in earlier times, before we had clocks and standardized calendars, humans used to mark time by the regular appearances of the moon. There are stone and bone carvings that suggest early humans were using the moon as a calendar as far back as 30,000 years ago. The Islamic lunar calendar is controlled purely by the moon. Many Asian cultures, the Assyrians, the Hebrews, Hindus, and the pre-Islamic Arabs combined the sun’s and moon’s motions into a single lunisolar calendar.

There are two ways we could have defined a moon-based month. One was to wait for the moon to complete one trip around the Earth and return to shine among the same stars it started in. The moon does that every 27.32 days – its sidereal period (from the Latin word siderus, meaning star or constellation). We use that approach for the sun. Aside from some minor tweaks like leap years and the slow precession of Earth’s axis, the sun returns to shine among the same stars after exactly one year.

The challenge with doing the same thing for the moon is that its schedule doesn’t line up with the sun. The moon orbits Earth 13.37 times in a year. That non-integer number of orbits means that the moon will complete some of its sidereal periods while it sitting at various angles from the sun in the sky. Sometimes it would be shining at night among the stars we are trying to link it to, sometimes it would complete an orbit near local dawn or dusk, and the rest of the time it would be sitting next to the sun, hiding both the moon and the stars we are measuring it against. And since the moon’s schedule is independent of Earth’s rotation, different parts of the world would need their own calendar.

Moreover, the moon’s orbit is an ellipse that is inclined by 5 degrees from the ecliptic, the big circle through the stars that the sun traces out due to Earth’s motion around it. The moon’s orbital inclination makes it ride up and down like a horse on a merry-go-round as it orbits Earth. Meanwhile, the moon’s elliptical orbit makes it speed up and slow down as it orbits the Earth. Each of those phenomena makes the moon dance around our sidereal reference stars and reduces the accurate timing we’d want in a calendar. So we don’t bother with that.

The far easier approach people have adopted is to use the appearance of the moon – its phases – to mark the passage of days. By choosing a lunar phase that only happens at night, like a full moon or a first quarter, we eliminate the interference by the bright sun. Since everyone on Earth sees the same phase, the lunar calendars match up globally. You’d need to wait for the moon to rise where you live, but that would only add a few hours of consistent error. We also needn’t worry about the moon’s dance among the stars since we don’t even need to see them in this system!

The phases we see on the moon are dictated by the angle between the sun and the moon while it orbits around the Earth. The moon is a waxing or waning crescent when it’s less than 90° from the sun in our sky. It is half illuminated when it is close to 90°, it is gibbous when it is more than 90°, and it is full when it is 180° from the sun.

But there’s one final twist to this story. While we are watching the moon, the Earth is moving, too – around the sun – and that affects the angles I talked about. If the Earth was stationary, the lunar phases would re-occur every 27.32 days. Instead, the moon needs an extra 2.21 days of orbital motion to reach the same angle every month, leading to a 29.53-day interval between moon phases – its synodic period (after the Greek word synodikos, or synodos, meaning assembly or conjunction).

The moon’s synodic period is much closer to our notion of a month. But the math still doesn’t quite work. The moon’s phases repeat 12.37 times each year, giving us an extra full moon to take care of every three years or so. The Islamic system doesn’t bother with that, so their calendar drifts continuously with time. The lunisolar calendars deal with that by inserting an extra intercalary month every two or three years to prevent moon-controlled events like Easter and Passover from drifting away from springtime.

Indigenous people have been marking the passage of time with the moon for millennia, recognizing that many years have 13 full moons and naming each full moon after what nature is doing at that time of the year. The Cree, Mohawk, and Ojibway link the turtle to the moon. The ring of scales around the turtle’s shell adds to 28, the number of days between full moons. The thirteen larger scales in the centre of the turtle’s shell represent each full moon! More information can be found at https://oneidalanguage.ca/oneida-culture/oneidalanguage-symbols/13-moons-turtle-island/

The Moon

Building on the preamble above, the moon will spend this week executing the third week of its lunar month – waning from full moon to third quarter. That will deliver darker and darker evening skies worldwide for those of us wanting to enjoy summer Milky Way treats – or winter treats, if you live in the Southern Hemisphere.

The moon reached its full phase this morning (Sunday) at 6:17 am EDT or 3:17 am PDT and 10:17 Greenwich Mean Time. When you see the bright moon rise in the southeast soon after 10 pm local time on Sunday night, it will still look full – but binoculars or a telescope will show you a thin strip of shadow and textured craters along its upper right limb. Last week here I talked about the western and native names for the July full moon and the fact that the moon will sit unusually low in the sky this week.

Tonight’s moon will outshine the faint stars of Capricornus (the Sea-Goat) that surrounds it. The moon will spend the rest of this week waning in phase and rising about 25 minutes later each night, allowing it to linger into the southwestern morning daylight like a ghostly, pale echo of the night.

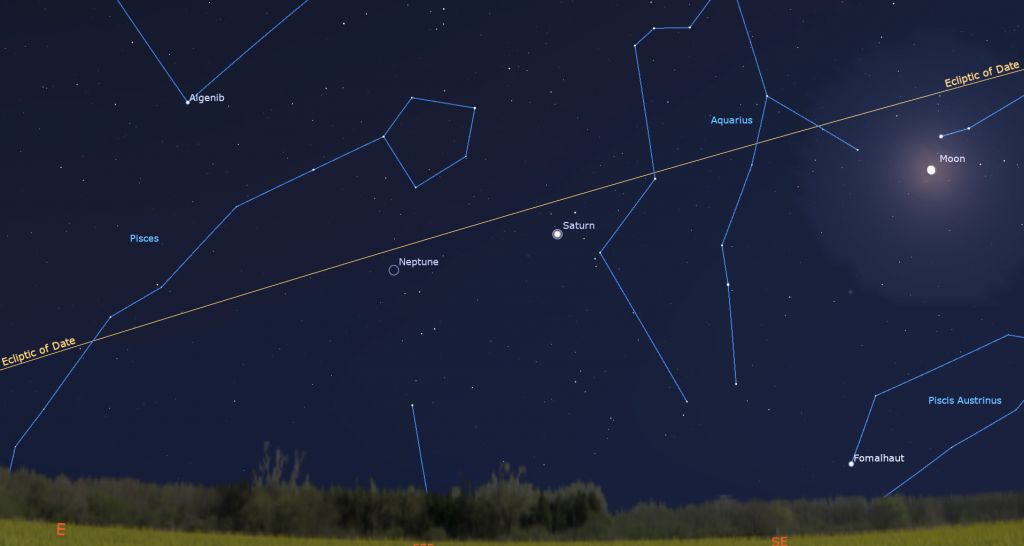

After spending Monday night in Capricornus, too, the waning gibbous moon will shift east into Aquarius (the Water-Bearer) where it will pose with the bright yellowish dot of Saturn shining a fist’s width to its left (or 10 degrees to the celestial east). The moon and Saturn will cross the sky together all night long. Hours later, observers in a zone stretching from eastern Africa and Madagascar, across most of southern Asia, northwest Indonesia, and most of China and Mongolia can watch the moon cross in front of (or occult) Saturn. Lunar occultations of planets can be watched with sharp, unaided eyes in a dark sky, and through binoculars and backyard telescopes, even when the sky is brighter. Exact times depend on your location, so use an app like Stellarium to look up your circumstances. You can also use the app to simulate where on the dark section of the moon Saturn will re-appear.

On Wednesday night in the Americas, the moon will swap sides from Saturn, and still shine in Aquarius. From Thursday night to Saturday the moon will swim along the crooked southern boundary of Pisces (the Fishes) and remain visible in the daytime sky until after noon.

The moon will complete three quarters of its orbit around Earth, measured from the previous new moon, on Saturday at 10:52 pm EDT or 7:52 pm PDT, which converts to Sunday, July 28 at 02:52 Greenwich Mean Time. At the third (or last) quarter phase the moon appears half-illuminated on its western, sunward side. Early-morning risers on Saturday and next Sunday can see the half-illuminated moon shining between Saturn and the bright pair of Mars and Jupiter, with winter’s bright star Capella shining to their upper left. Take a picture!

The Planets

Mercury and Venus will continue to lurk just above the west-northwestern horizon after sunset this week. To see them, you’ll need to wait until the sun has fully set, then use binoculars to scan above the west-northwestern horizon. The key will be to have an unobstructed view that is free of clouds and excessive haze.

Very bright Venus, currently in Cancer (the Crab), will appear just to the left of the spot on the horizon where the sun disappeared. At mid-northern latitudes, the best time to look for Venus will start at about 9:15 pm local time. Don’t worry if you miss it, though – Venus will be our brilliant “Evening Star”, and nice and high in the sky, throughout this coming Fall and Winter.

Meanwhile, speedy Mercury, though it is about 50 times fainter than Venus nowadays, should be easier to see because it is much farther from the sun and lingers longer after sunset – but only for the first part of this week. On Monday evening, Mercury will reach its widest separation of 26.9 degrees east of the sun, and its maximum visibility for its current apparition. With Mercury positioned in the western sky below the slanted evening ecliptic, this appearance of the planet will be a very poor one for Northern Hemisphere observers, but it will offer the best views of the year for observers located near the equator and farther south. The optimal viewing times at mid-northern latitudes will start around 9:15 pm local time. Viewed in a telescope (but only after the sun has disappeared) the planet will exhibit a waning, half-illuminated phase.

If you spot one of the two inner planets, try for the other. They’ll be a generous fist’s diameter apart, with Mercury generally to Venus’ upper left.

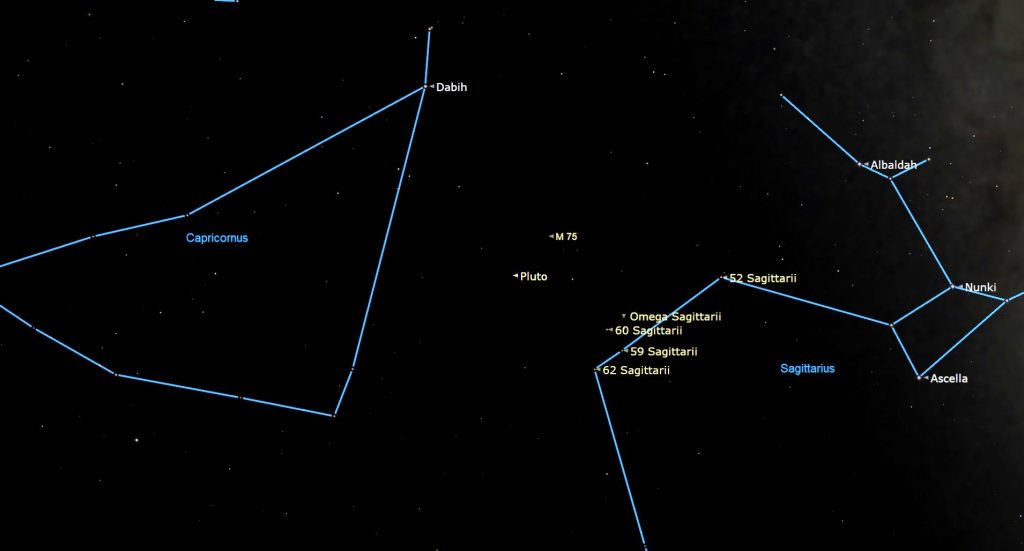

On Tuesday night the dim and distant dwarf planet designated (134340) Pluto will reach opposition for 2024. The number in the brackets in its designation is so large because so many other asteroids and minor planets were discovered before Pluto was in 1930. The first minor solar system body to be discovered was (1) Ceres, by Giuseppe Piazzi at Palermo Astronomical Observatory in Sicily, on January 1, 1801.

On Pluto’s opposition night, the Earth will be positioned between Pluto and the sun, minimizing our distance from that outer world and maximizing Pluto’s visibility. This year, Pluto will close to within 5.09 billion km, or 283 light-minutes from Earth. Unfortunately, Pluto will shine with an extremely faint visual magnitude of +14.4 that is far too dim for visual observing through a small backyard telescope.

Pluto will be located in the sky about a palm’s width to the upper left (or 5.5 degrees to the celestial north-northeast) of the four medium-bright stars named Omega, 59, 60, and 62 Sagittarii, which huddle well to the left (celestial east) of Sagittarius’ Teapot-shaped asterism. Alternatively, aim your telescope a generous thumb’s width to the lower left (or 2.2 degrees southeast of) the globular star cluster named Messier 75. Even if you can’t see Pluto directly, you will know where it is lurking. TO better see the globular cluster, wait a few nights for the moon to move away.

We don’t have to stay up quite so late to see Saturn now. This week, the yellowish ringed planet will rise over the eastern rooftops by 11:30 pm local time. Saturn will spend the next 10 months among the stars of eastern Aquarius (the Water-Bearer). Saturn’s rings, which will effectively disappear when they become edge-on to Earth next March, already look very narrow against the planet’s globe. Good binoculars can hint at Saturn’s rings, and any telescope will show them to you. For telescope-owners, Earth’s perspective of the Saturn system this year and next will cause its moons to align in the plane of the rings and produce frequent transits of Saturn’s moons and their black shadows across its disk.

Neptune will rise about 20 minutes after Saturn and chase it across the sky every night. The remote, blue planet will be spending this year in western Pisces (the Fishes), a fist’s width to the lower left (or 11° to the celestial ENE) of Saturn. Neptune will also be located a bit more than a thumb’s width to the upper left (or 2° north) of a medium-bright star named 27 Piscium, allowing them to share the view in binoculars. Other less-brilliant stars nearby named 29 Piscium, 24 Piscium, and 20 Piscium will help guide you to Neptune with a backyard telescope or good, strong binoculars. For now, you’ll need to look at Neptune while it’s higher and the sky is dark between about 1 and 4:30 am local time.

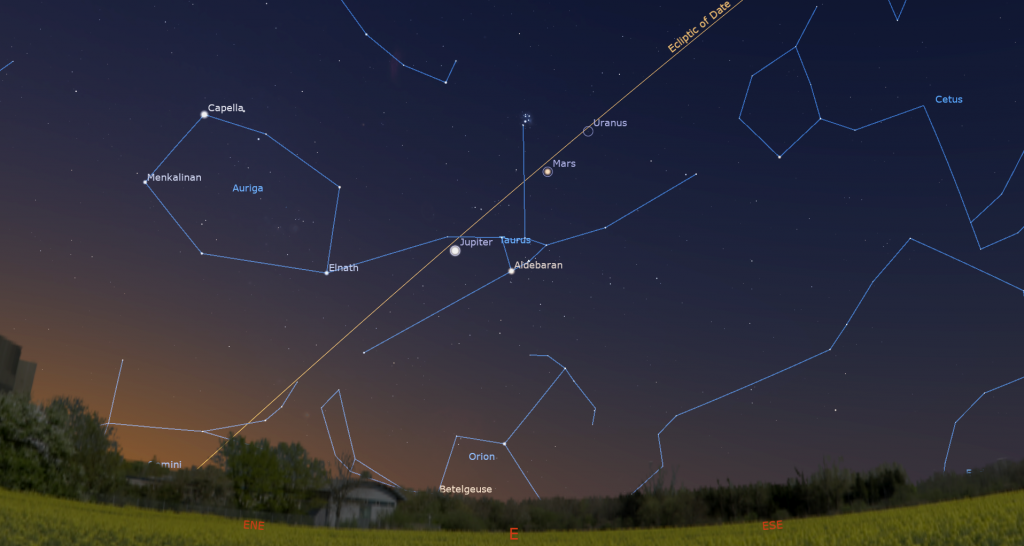

The next planets to rise overnight will be bright, reddish Mars and far fainter Uranus. Reddish Mars will clear the rooftops to the east by about 3 am local time and then remain in sight until almost sunrise, when it will appear partway up the eastern sky, with brilliant Jupiter to its lower left. If you head outside while the sky is still dark, the brightest stars of Aries (the Ram) and Perseus (the Hero) will twinkle well above Mars. In a telescope, Mars will display a small, rusty-coloured disk. Its position on the far side of the sun from Earth is keeping the planet looking small until later this year. If you check it out, notice that Mars is only 90%-illuminated because its angle from the sun is so great.

Mars’ eastward orbital motion has been almost enough to hold the planet in place while everything else shifts west each day due to Earth’s motion around the sun. (That shift causes the constellations to change with each season.) As a consequence, Mars has been racing past the other planets. It passed Saturn and then Neptune last April, and Uranus last week. Now it’s heading for a tight conjunction with Jupiter on August 15. Mark your calendars!

This week, Mars will continue to slip away from Uranus, carrying that blue-green planet farther to Mars’ upper right each morning. They’ll just squeeze into the field of view of binoculars until mid-week. Uranus will sit about a palm’s width from the Pleiades star cluster all year, long after Mars has moved away.

Early risers can’t miss Jupiter now. The giant planet is now well and truly dominating the eastern sky before sunrise. This week it will be rising around 2:20 am local time and then gleaming in the east until sunrise. Take note of the brightest star in Taurus (the Bull), the red giant Aldebaran, shining to Jupiter’s lower right. The planet and the bull will eventually migrate into the late-night and then evening sky later this year as the Earth swings around the sun and varies our perspective of the night sky.

Binoculars will show Jupiter’s four Galilean moons named Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto lined up beside the planet. Those moons complete orbits of the planet every 1.7, 3.6, 7.2, and 16.7 days, respectively. If you see fewer than four moons, then one or more of them is crossing in front of or behind Jupiter, or hiding in Jupiter’s dark shadow – or two of the moons are very close together or occulting one another. All four of them will huddle to the west of Jupiter on Thursday morning. Even a small, but decent quality telescope can show you Jupiter’s dark belts and light zones, which are aligned parallel to its equator. With a better grade of optics, Jupiter’s Great Red Spot, a cyclonic storm that has raged for hundreds of years, becomes visible for several hours when it crosses the planet every 2nd or 3rd night. For observers in the Americas, that GRS will cross Jupiter’s disk on Tuesday, Thursday, and next Sunday morning. If you have any coloured filters or nebula filters for your telescope, try enhancing the spot with them.

Sights for Moonlit Nights

If you missed last week’s tour of the bright stars and treats for binoculars while the bright moon is shining in the evening sky, I posted it here.

Public Astronomy-Themed Events

Every Monday evening, York University’s Allan I. Carswell Observatory runs an online star party – broadcasting views from four telescopes/cameras, answering viewer questions, and taking requests! Details are here. They host in-person viewing on the first clear Wednesday night each month. Other Wednesdays they stream views online via the observatory YouTube channel. Details are here.

On Saturday, July 27 from 10 pm to midnight, RASC Toronto Centre will host Family Night at the David Dunlap Observatory for visitors aged 7 and up. You will tour the sky, visit the giant 74” telescope, and view celestial sights through telescopes if the sky is clear. This program runs rain or shine. Details are here, and the link for tickets is at ActiveRH.

On Sunday afternoon, July 28 from 12:30 to 1:30 pm EDT, head to the David Dunlap Observatory for in-person DDO Sunday Sungazing. Safely observe the sun with RASC Toronto astronomers! During the session, which is for ages 7 and up, a DDO Astronomer will answer your questions about our closest star – the sun! Registrants will be given an eclipse viewer, learn how the sun works and how it affects our home planet, view the sun through solar telescopes, weather permitting, and visit the giant 74” telescope. More information is here and the registration link is here.

Keep your eyes on the skies! I love getting questions and requests. Send me some!