More Meteors Briefly, Merry Perihelion, a Paucity of Planets, and the Stunning Stars of January!

This wide field photograph of the sky shows Orion at left and Taurus to the upper right. The stars have been slightly overexposed to emphasize their colours and relative brightnesses. Normally, reddish Betelgeuse at Orion’s shoulder (left above centre) is the same brightness as blue Rigel at Orion’s opposite foot. But recent images shows Betelgeuse has become markedly dimmer – possibly a pre-cursor to an imminent supernova explosion. Or, it may just be one of Betelgeuse’s periodic pulsations.

Happy New Year and Merry Perihelion, Stargazers!

Here are your Astronomy Skylights for the week of December 29th, 2019 by Chris Vaughan. Feel free to pass this along to your friends and send me your comments, questions, and suggested topics. You can also follow me on Twitter as @astrogeoguy! Unless otherwise noted, all times are Eastern Time. To subscribe to these emails please click this MailChimp link.

I can bring my Digital Starlab portable inflatable planetarium to your school or other daytime or evening event. Contact me through AstroGeo.ca, and we’ll tour the Universe together!

The moon will spend New Year’s Eve shining above celebrants the world over – but it won’t spoil the annual, but quick Quadrantids meteor shower. After sunset, lovely Venus will shine brightly in the western sky, and Mars will slide towards its rival in the pre-dawn east. We’ll tour the bright stars of January, and tell you how to look for Vesta and a comet. Here are your Skylights!

Earth Closest to the Sun

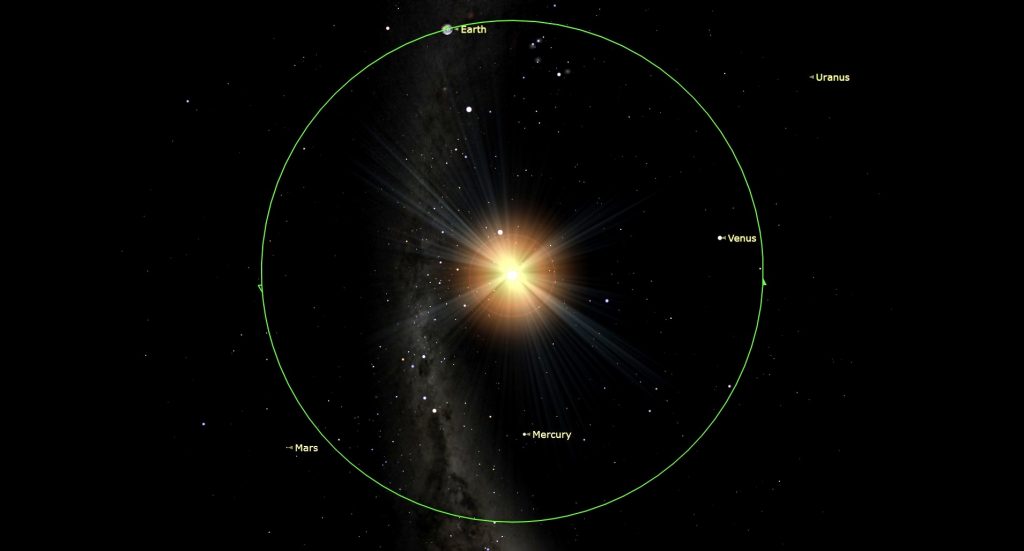

Merry Perihelion! On Sunday morning, January 5, the Earth will reach perihelion, its closest point to the sun for the year. On that date our distance from Sol will be 147,096,000 km. Do you feel warmer? You shouldn’t – as winter-chilled Northern Hemisphere dwellers will attest, daily temperatures on Earth are not controlled by our proximity to the sun, but by the number of hours of daylight we experience, which is only about 9 hours at this time of the year in the Great Lakes region.

The Moon and Planets

Tonight (Sunday) the moon will appear as a beautiful, slim crescent among the dim stars of Capricornus (the Sea-Goat) in the southwestern sky from dusk until about 8 pm local time. All afternoon, eagle-eyed skywatchers can look for the moon in the daytime sky, too.

The waxing crescent moon will finish 2019 while travelling through Aquarius (the Water-Bearer). The moon will pass several finger widths below dim Neptune on New Year’s Eve. But a nearby moon is not the time to look for Neptune; take note of where the moon is, and by extension Neptune, and then seek out the remote planet on a night when the moon has moved away.

For the rest of the week, the moon will traverse the crooked boundary shared by the constellations Cetus (the Sea-Monster) and Pisces (the Fishes). At 11:45 pm EST on Thursday night, the moon will reach its first quarter phase – so-named because the moon has completed the first quarter of its orbit around Earth. At first quarter, the relative positions of the Earth, sun, and moon cause us to see the moon half-illuminated – on its eastern side.

At first quarter, the moon always rises around noon and sets around midnight local time, so it is conveniently positioned for observing before youngsters’ bedtimes. The evenings around first quarter are excellent for looking at the lunar terrain while it is dramatically lit by low-angled sunlight. Every night this week, the terminator, the pole-to-pole boundary that divides the lit and dark hemispheres will migrate across the moon’s face – offering breathtaking views in your binoculars and telescopes.

On the coming weekend, the now waxing gibbous (i.e., more than half-illuminated) moon will hop through the rough circle of stars that form the head of Cetus. On Saturday night the moon will sit about a palm’s width to the right (or 6 degrees to the celestial west) of those stars. The following night, the moon will shift to sit to their left (celestial east).

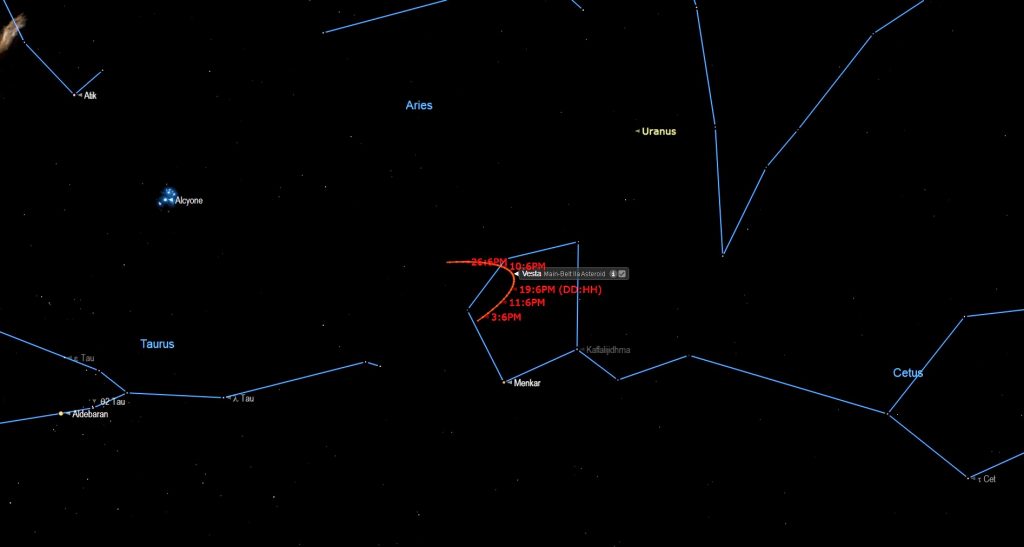

On Sunday night, take a moment to look for a modestly bright star sitting about three finger widths to the moon’s right. That star is named Mu (μ) Ceti, and Al Kaff al Jidhmah. This week the large main belt asteroid designated (4) Vesta will be positioned less than a finger’s width below Mu Ceti. Vesta is considerably dimmer than that star, but binoculars and backyard telescopes will reveal the asteroid to you.

Normally, asteroids move fairly rapidly through the distant background stars. For the past few months, Vesta has been moving westward. But on Wednesday, Vesta will complete that retrograde loop and return to normal eastward motion. In order to reverse direction, Vesta will need to stand still for a night or two, centred on Wednesday. All solar system bodies that orbit the sun farther than Earth perform these retrograde loops once per year. The object itself isn’t changing direction, though. Instead, Earth is passing it on the faster “inside track” – so parallax makes the object appear to move backwards for a few months from our point of view.

We’ve entered an extended period there will be very few planets to look at during the evening hours. Jupiter had its date with the sun (solar conjunction) late last week, and Saturn will soon do the same. Those two planets will both reappear in the eastern pre-dawn sky in a matter of weeks, but it will be months before they once again rise before late evening. In the meantime, they will meet in spectacular fashion with Mars next March. And when the two giant planets do return to evening skies next summer, they will be close to one another!

For now, our brilliant sister planet Venus will continue its lengthy winter appearance – shining very brightly in the southwestern evening sky, starting in twilight and setting at 7:30 pm local time in a darkened sky. Viewing Venus in your telescope during the upcoming weeks will reveal that its shape is less than fully round, and it will continue to wane in phase as it swings wider from the sun. Use your telescope on Venus while the planet is higher in the sky and the sun has completely set – at around 5:30 pm local time. That way, you’ll reduce the blurriness caused by looking through so much of Earth’s atmosphere.

After easy-to-see Venus, we will have to settle for the harder-to-see ice giant planets Uranus and Neptune. Despite their relatively dim magnitudes and small disk sizes, the delightful colours of those two remote planets make them worthy of a look in backyard telescopes.

Blue-green Uranus is observable from dusk until the wee hours of the night. It is located a generous palm’s width to the left (or 7° to the celestial east) of the modest stars that form the V-shaped constellation of Pisces (the Fishes). Uranus is also positioned below (or to the celestial south of) the medium-bright stars of Aries (the Ram), and above the ring of stars that form the head of Cetus (the Sea-Monster).

Shining at magnitude 5.7, Uranus is bright enough to see under dark sky conditions with unaided eyes and with binoculars – or through small telescopes under less-dark conditions. If you view Uranus at about 7:45 pm local time, it will be highest in the southern sky – and you’ll be looking through the least amount of Earth’s disturbing atmosphere.

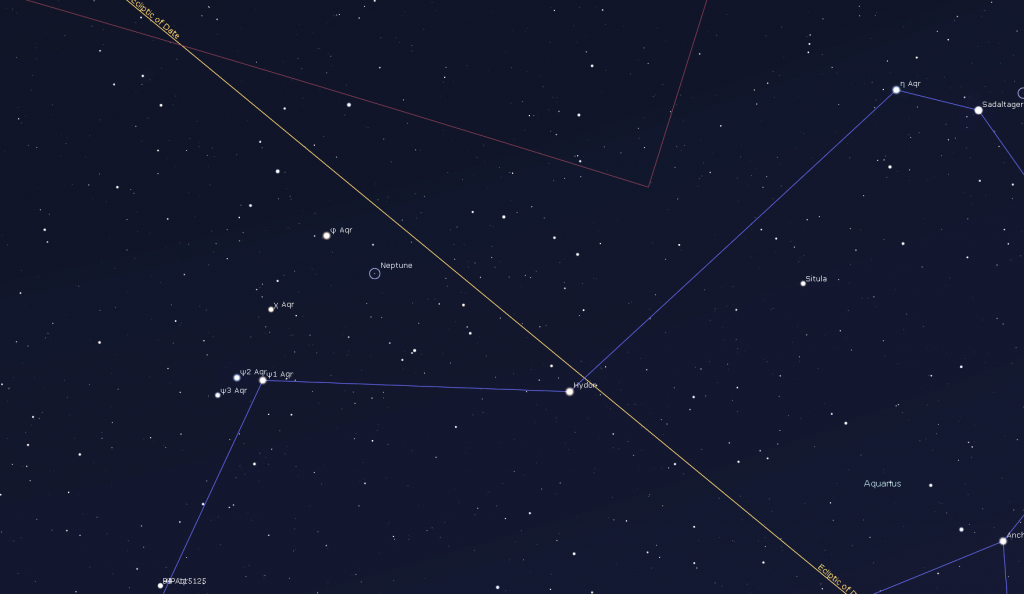

This week, distant and dim, blue Neptune will be lost from view well before it sets at about 10:35 pm local time. You should try to observe Neptune as soon as the sky is dark, when the planet is higher – somewhat less than halfway up the south-southwestern sky. Slow-moving Neptune is situated among the stars of eastern Aquarius (the Water-Bearer), and is positioned a finger’s width to the right (or 1 degree to the celestial west) of a medium-bright star named Phi (φ) Aquarii.

Both blue Neptune and that golden-coloured star will appear together in the field of view of a backyard telescope at low power. Find Phi Aquarii first and then locate nearby Neptune. Remember that binoculars will display the true relative positions of the objects, but a telescope will flip and/or mirror-image the view. (To find out what your telescope does to the image, see how it changes the view of the moon, and make a note of the result.)

Mars continues to shine in the eastern pre-dawn sky this week (and for months to come). The red-tinted planet will be rising at about 4:35 am local time and remaining visible until dawn. The relative positions and combined orbital motions of Earth and Mars are causing Mars to appear in roughly the same place in the sky at the same times every morning. However, the planet is moving rapidly eastward through the distant background stars, because they rise four minutes earlier every morning.

Last week, Mars was located near the bright stars of Libra (the Scales). This week, Mars will move towards the three white claw stars of Scorpius (the Scorpion). If you have a low, open eastern horizon, watch for Mars’ stellar rival, the bright, ruddy star Antares, sitting more than a fist’s diameter below the planet. They’ll have a meeting in a few weeks. From now until October, 2020, Mars will continually grow in brightness – and will increase in apparent size when viewed in telescopes.

The Bright Stars of January

After a murky autumn, the cold clear nights of winter have arrived. Let’s review the many bright stars you can pick out with your unaided eyes in the evening sky over the next month or so. A star will shine brightly due to two primary causes – because it is closer to us, and/or because it is emitting more light than average. (Astronomers call this phenomenon high luminosity.) I’ve put the stars’ brightness rankings (3rd brightest in the night sky, 7th, etc.) in brackets. Remember that all of these stars will appear in the same place at the same time on the same dates every year.

Let’s start in the western half of the sky because those stars set first. If you have an open southwestern horizon, look as soon as it’s dark for bright Fomalhaut (18th) very low in the southwestern sky. Facing directly west, look for the three bright corner stars of the Summer Triangle (still!) shining brightly in the early evening. The lowest of the three stars is Altair (12th) in Aquila (the Eagle). A bit higher, and about 3.4 outstretched fist diameters to the right of Altair, is Vega (5th) in Lyra (the Lyre). Deneb (19th) sits well above and between the lower two. All three stars are hot, bluish white stars. Deneb represents the tail of Cygnus (the Swan). On a moonless night, you should be able to see the great bird flying head-down into the west – along the Milky Way. This week Altair and Vega set about 8:15 and 9:50 pm local time, respectively. Deneb sets much later – at about 2 am local time.

Next, turn about face and look about halfway up the eastern sky. Bright yellowish Capella (6th) is on the left and orange-tinted Aldebaran (14th) is located about three fist widths to the right of it. Capella is the brightest star in the large circular constellation of Auriga (“Oar-EYE-gah”) (the Charioteer), while Aldebaran represents the baleful red eye of Taurus (the Bull), whose triangular face is tilted sideways to the left. Both of these constellations will climb higher in late evening.

The well-known constellation of Orion (the Hunter) sits directly below Aldebaran. His eastern shoulder is the old and bright reddish star Betelgeuse (11th), and his opposite foot is a bluish star of similar brightness named Rigel (7th). These two stars are hundreds of light-years away. You may have seen reports that Betelgeuse has noticeably dimmed in brightness recently. Normally, it shines with a brightness that is comparable to Rigel. But it is now definitely dimmer. The very massive star is at the stage of its life when it will explode in a supernova. This dimming may be a pre-cursor to that cataclysmic event. But don’t hold your breath – Betelgeuse has dimmed before, and could hang on for another 100,000 years. In any event, if it does explode, we’re in no danger – the star is hundreds of light-years away from us.

Orion’s three-starred belt is a highlight of the winter sky. From east to west (lower left to upper right) the stars are Alnitak (30th), Alnilam (29th), and Mintaka (67th). The three stars are evenly spaced – almost exactly 1.3° (that’s about a thumb’s width or about three moon diameters) apart. Orion’s western shoulder is marked by bluish white star Bellatrix (26th). His his opposite foot is the star Saiph (53rd).

To the left (or celestial north) of Orion sits the zodiac constellation of Gemini (the Twins). Its brightest stars are yellowish Pollux (17th) and pale white Castor (23rd). Like many twins, it is a challenge to keep straight which star is which. Castor, the higher star, rises first, just as “C” precedes “P” in the alphabet.

The night sky’s brightest star rises in the sky below Orion after 7:30 pm local time. Sirius (1st), also called the Dog Star because it resides in the constellation of Canis Major (the Large Dog), is a very hot, bluish-white star. It’s so bright because it is our neighbour – located “just up the street” at only 8.6 light-years away. Sirius has a reputation for twinkling vigorously, with flashes of pure colour. This happens because it sits low in the sky for mid-latitude observers, and we see it shining through a thicker blanket of refracting air. Sirius’ bright little sibling Procyon (8th) sits 2.5 fist widths to the upper left (or 25° to the celestial north), below Gemini, in the constellation of Canis Minor (the Little Dog). It, too, is relatively close to Earth.

In January, those bright eastern stars reach their highest points, in the southern sky, before midnight – perfect to catch your eye through a south-facing window before bedtime. Good hunting!

Meteor Shower News

Named for a now-defunct constellation near the north celestial pole called Quadrans Muralis (the Mural Quadrant), the annual Quadrantids meteor shower runs from December 30 to January 12 – but the shower’s most intense period, when 50 to 100 meteors per hour can occur, lasts only about 6 hours surrounding the peak, which is predicted to occur on Saturday at 09:00 GMT. That’s 4 am Eastern time. At that time, the Earth will be traversing the thickest part of the debris field.

Many Quadrantids are bright fireballs owing to the shower’s source, the asteroid 2003EH. The best time for viewing Quadrantids will be before dawn on Saturday morning, when the shower’s radiant, which is beyond the tip of the Big Dipper’s handle, will be high in the northeastern sky. The half-illuminated moon will set after 1 am local time on the shower’s peak date, leaving the pre-dawn sky dark for meteor-watchers.

To see the most meteors, find a wide-open, dark location, preferably away from light polluted skies, and just look up with your unaided eyes. The fields of view of binoculars and telescopes are too narrow to be useful for meteors. Don’t spend too much time watching the radiant because the meteors appearing near that location will be exhibit short streaks. Try not to look at your phone’s bright screen – it’ll ruin your night vision. Just keep your eyes heavenward – even while you are chatting with companions. Don’t forget to bundle up, and Happy hunting!

Andromeda’s Family – the Wings of Pegasus

If you missed last week’s tour of Pegasus, I posted it here.

Binocular Comet Update

A relatively modest comet will be traversing the northeastern evening sky this winter. Designated C/2017 T2 (PanSTARRS), it is currently shining at magnitude 8.4. That means that it is conveniently positioned for evening viewing in good binoculars or a backyard telescope. I posted a sky chart showing its path over the next month here.

The comet is about halfway up the northeastern sky after dusk – and it moves higher in mid-evening as the Earth’s rotation carries the sky east to west. Comets move across the background stars faster than planets wander. This week, the comet will be just inside the southern boundary of Camelopardalis, and positioned a slim palm’s width to the lower left (or 5 degrees to the celestial north of) the bright, white star Mirfak in Perseus (the Hero). Over the next seven nights the comet will move a distance of three finger widths of sky, towards the W-shaped constellation of Cassiopeia (the Queen).

Viewed in binoculars and telescopes, Comet PanSTARRS will appear as a dim, fuzzy patch that might exhibit a faint greenish centre. It’s still too early to see a tail, but the comet is expected to brighten much more in the coming months. Stay tuned for updates!

Public Astro-Themed Events

During the Holidays, organizations have suspended their public events until January.

This Winter spend a Sunday afternoon in the other dome at the David Dunlap Observatory! On Sunday afternoon, January 12, from noon to 4 pm, join me in my Starlab Digital Planetarium for an interactive journey through the Universe at DDO. We’ll tour the night sky and see close-up views of galaxies, nebulas, and star clusters, view our Solar System’s planets and alien exo-planets, land on the moon, Mars – and the Sun, travel home to Earth from the edge of the Universe, hear indigenous starlore, and watch immersive fulldome movies! Ask me your burning questions, and see the answers in a planetarium setting – or sit back and soak it all in. Sessions run continuously between noon and 2 pm, and repeat from 2 to 4 pm. Ticket-holders may arrive any time during the program. The program is suitable for ages 3 and older, and the Starlab planetarium is wheelchair accessible. For tickets, please use this link.

Keep looking up, and enjoy the sky when you do. I love questions and requests – so, send me some!