Morning Moon Passing Sol Highlights Hercules on High, Our Star is Afar, Mercury Buzzes the Bees, and Matariki Returns!

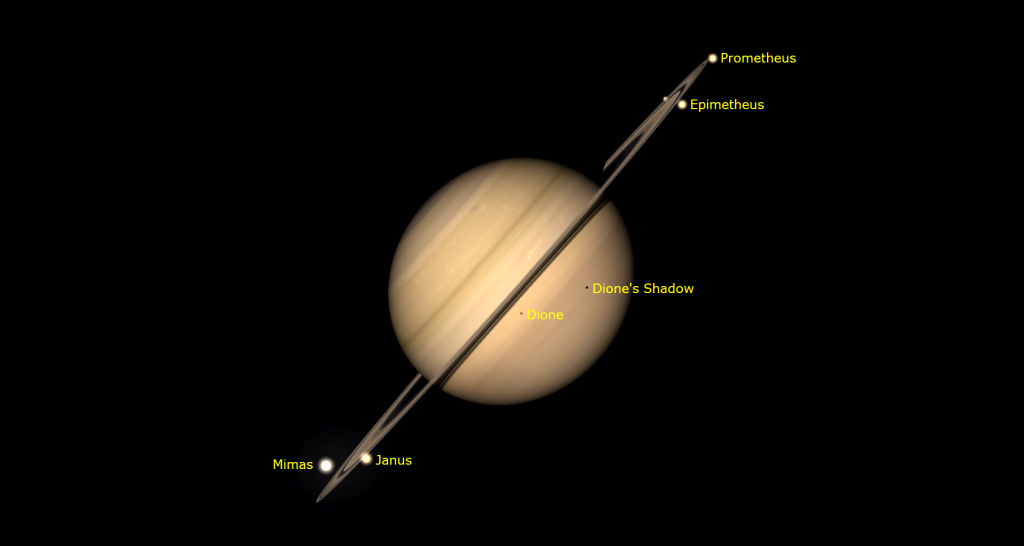

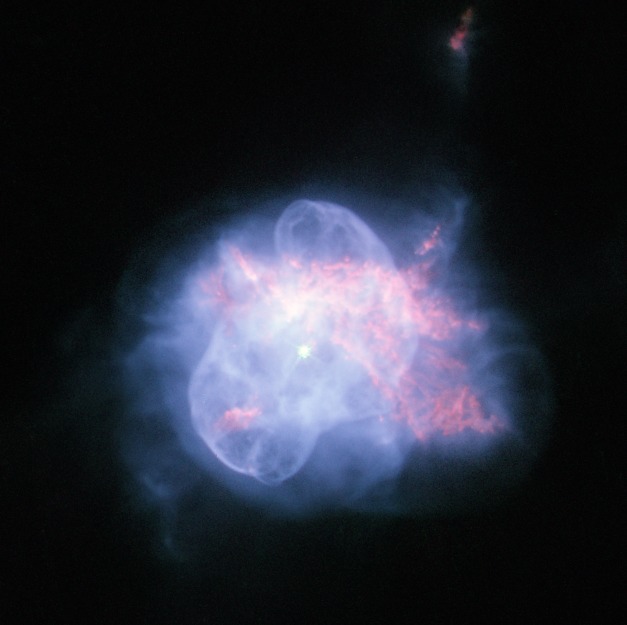

This image of Messier 13, the Great Globular Star Cluster in Hercules was imaged by my friend Claudio Oriani in Richmond Hill, Ontario on May 30, 2023 using an 8″ SCT telescope. The cluster, also known as NGC 6205, is 24,000 light-years away from our sun. The cluster appears as a faint fuzzy patch in binoculars, and sugar spilled in black velvet in a good backyard telescope under dark skies. See more of Claudio’s work at his site https://www.wondersofthesky.com/

Hello, Summer Stargazers!

Here are your Astronomy Skylights for the week of June 30th, 2024 by Chris Vaughan. Feel free to pass this along to your friends and send me your comments, questions, and suggested topics. You can also follow me on Twitter as @astrogeoguy! Unless otherwise noted, all times are expressed in Eastern Time. To subscribe to these emails please click this MailChimp link.

If you’d like me to bring my Digital Starlab portable inflatable planetarium to your school or other daytime or evening event in Simcoe, Grey, and Bruce Counties, or deliver a virtual session anywhere, contact me through AstroGeo.ca, and we’ll tour the Universe, or the Earth’s interior, together! My book with John A. Read entitled 110 Things to See With a Telescope is a guide to viewing the deep sky objects in the Messier List – for both beginners and seasoned astronomers. DM me to order a signed copy!

The waning crescent moon will pose prettily with several morning planets before it passes the sun at new moon this week. That will leave evenings worldwide dark for exploring summer sights in Hercules. Earth will be farthest from the sun, the Maori’s will celebrate the return of Matariki, Mercury will cruise through the Beehive Cluster after sunset, Ceres will reach opposition, and Saturn will become the first bright planet to join the evening sky. Read on for your Skylights!

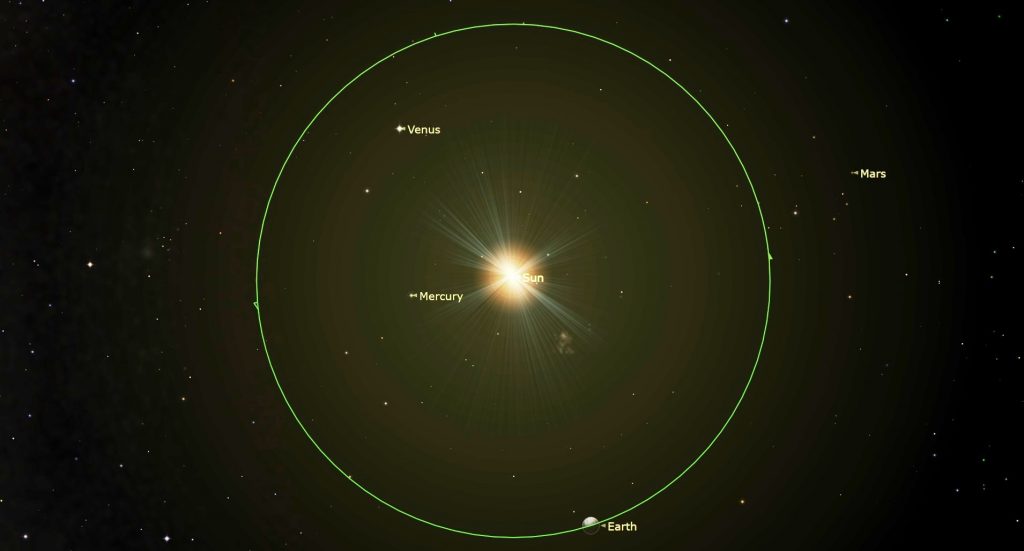

Earth at Aphelion

On Thursday, July 4 at 1:00 am EDT or 05:00 Greenwich Mean Time, Earth will reach aphelion, its greatest distance from the sun for this year. The aphelion distance of 152.1 million km is 1.67% farther from the sun than the mean Earth-sun separation of 149.6 million km, which is also defined to be 1 Astronomical Unit or 1 A.U. Earth’s minimum distance from the sun, or perihelion, will occur on January 4, 2025. In a telescope equipped with a proper solar filter, the July 4 sun will appear a little smaller than it looks in January.

We can’t merely divide our 365.25-day year into four 91.3-day-long seasons. Planets in elliptical orbits move faster when they are closer to the sun and slower when they are farther away. Since Earth is moving slower at aphelion in July, summer in the Northern Hemisphere is 93.6 days long, or about five days longer than winter’s 89.0 days – hooray! Spring is 92.8 days long, leaving autumn at 89.8 days.

Our seasonal temperatures are not controlled by our distance from the sun. It’s the duration and intensity of sunshine we receive that makes the most difference – and that is controlled by the degree to which Earth’s axis of rotation is tipped toward (or away from) the sun.

The sun has been extremely active recently, ejecting flares and clouds of charged plasma into space more frequently. If that material crosses Earth’s orbit while we are there, it triggers aurorae, as it did on May 10, 2024. Interestingly, at aphelion, Earth would be a slightly smaller target.

It’s Matariki!

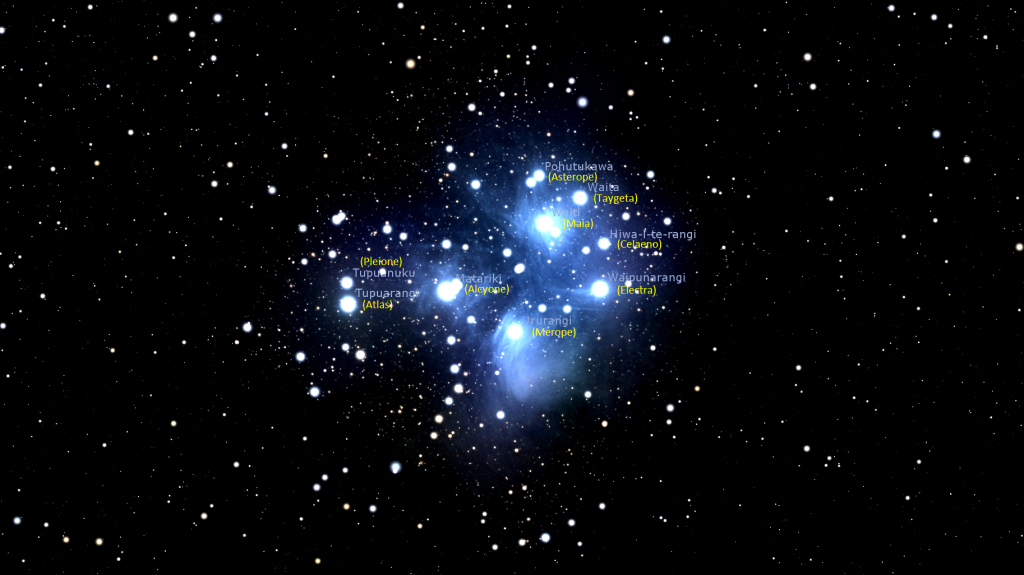

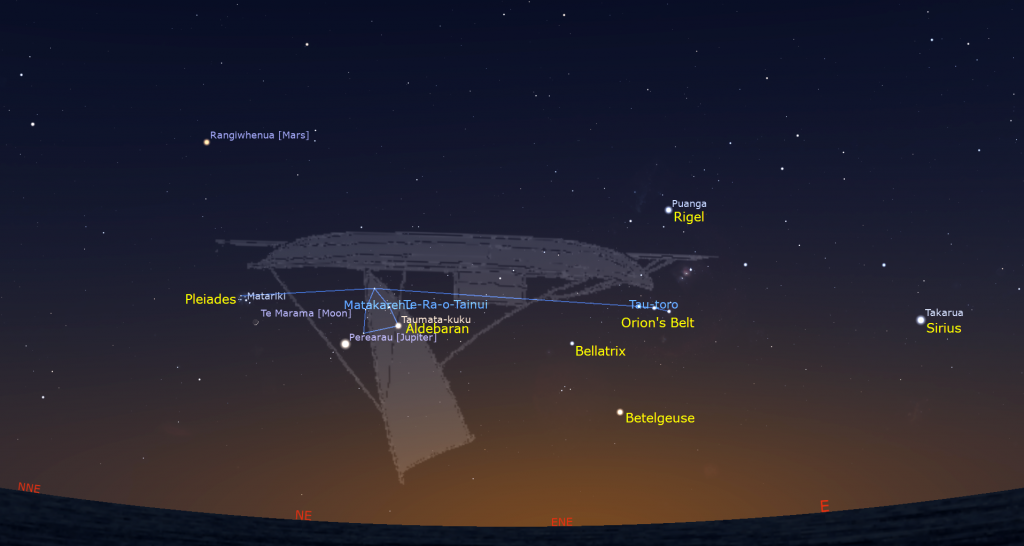

Matariki is the Māori name for the Pleiades star cluster in Taurus (the Bull). At this time of year, mid-winter in the Southern Hemisphere, Taurus rises long enough before sunrise for the cluster to become visible low in the eastern sky after several months of absence from the sky for New Zealanders. Matariki’s return to sight during Pipiri (June/July) marks the beginning of the Māori new year. This year, Matariki began yesterday, on June 29. Some groups opt to use the return of the bright star Puanga, better known to us as Rigel in Orion (the Hunter), instead. In 2022, Matariki became a national holiday in New Zealand – because of astronomy!

The word Matariki is an abbreviation of Ngā Mata o te Ariki, “Eyes of God” – referring to Tāwhirimātea, the god of the wind and weather. In the Maori story of creation, Tāne Mahuta, the god of the forest, separated his parents Ranginui and Papatūānuku. His upset brother Tāwhirimātea tore out his eyes, crushed them into pieces, and threw them into the sky to become the stars.

Traditionally, Maori communities, or iwi, would gather together at night during a time of the constellation’s prominence, making use of the period between harvests to celebrate and make offerings for a bountiful future.

Traditions hold that the visual appearance of the cluster was said to predict the success of the season ahead. Clear, bright stars are a good omen, and hazy stars predict that the rest of winter during July-August will be cold and harsh. Even though one common name for the Pleiades is the Seven Sisters, nine bright stars in the cluster are visible to sharp-eyed observers. For Māori the brightness of each individual star predicts the fortunes connected to a specific thing that star represents in Māori life, such as the wind, or food that grows in trees.

There is an excellent source on Matariki at https://www.tepapa.govt.nz/discover-collections/read-watch-play/matariki-maori-new-year.

Māori Star Name and Aspect Common Name Designation

Matariki (the mother star, wellbeing) Alcyone Eta Tauri

Pōhutukawa (lost loved ones) Sterope 21 Tauri

Waitī (freshwater, wetlands) Maia 20 Tauri

Waitā (ocean, fish) Taygeta 19 Tauri

Waipuna-ā-rangi (rain) Electra 17 Tauri

Tupuānuku (soil crops) Pleione 28 Tauri

Tupuārangi (tree crops, birds) Atlas 27 Tauri

Ururangi (winds) Merope 23 Tauri

Hiwa-i-te-rangi (the future) Caleano 16 Tauri

(Source: New Zealand Aotearoa Ministry for the Environment)

The Moon

Earth’s natural night-light will be extinguished this week while the moon makes its monthly trip past the sun. That will deliver dark, moonless evenings for stargazers worldwide and moon views in morning.

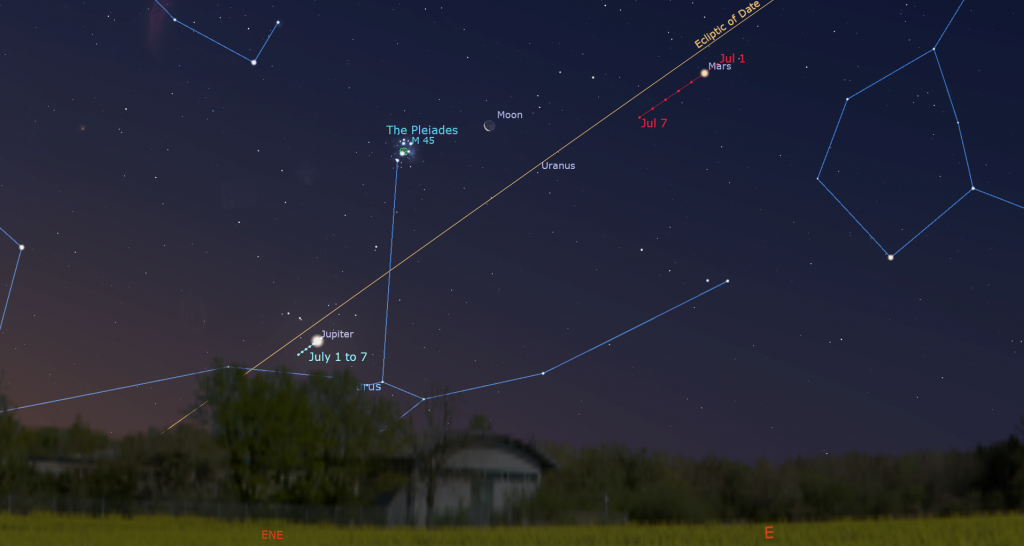

Tonight (Sunday), the pretty, waning crescent moon will rise around 2 am local time and then greet early risers in the east. Watch for the reddish dot of Mars shining several finger widths below the moon on Monday morning. If the sky hasn’t brightened too much yet, you might glimpse the brightest stars of Aries (the Ram), named Hamal and Sheratan, shining above the moon.

On Tuesday morning, the moon will appear even slimmer as it slips into Taurus (the Bull) for a three-day stay. The moon will be positioned between Mars and brighter Jupiter, which will gleam to their lower left. The bright little Pleiades star cluster will sparkle a few finger widths to the moon’s left (or celestial northeast), close enough for them to share the view in binoculars. The scene will make a lovely widefield photograph when composed with some nice foreground scenery. The gathering will remain visible until almost sunrise. If you are out while the sky is darker, your photo might also capture the fainter planet Uranus. Its blue-green dot, which is visible in binoculars, will be located a couple of finger widths below the moon and offset a little to the right – allowing they, too, to share the view in your binoculars.

Another 24 hours of orbital motion will carry the very slender moon several finger widths to the upper left (or 4 degrees to the celestial north) of the bright planet Jupiter on Wednesday morning. Look for the pair climbing the eastern sky from about 4 am local time until sunrise. Quality binoculars should show you Jupiter’s own four brightest moons, the ones discovered by Galileo in January, 1610. Taurus’ brightest star, the red giant Aldebaran, will be twinkling below Jupiter. Take another photo!

On Thursday morning before dawn, the moon will be razor-thin, only 3%-illuminated, while it shines below (or celestial southeast of) the bull’s northern horn-tip star, Elnath. Jupiter and Mars will gleam well off to their upper right. Unless you live near the tropics, that will be your last glimpse of the moon before it passes the sun.

On Friday, July 5 at 6:57 pm EDT or 3:57 pm PDT and 22:57 GMT, the moon will officially reach its new moon phase. At that time our natural satellite will be located in Gemini (the Twins), 4.5 degrees north of the sun. While new, the moon is travelling in space between Earth and the sun. Since sunlight can only illuminate the far side of the moon, and the moon is in the same region of the sky as the sun, it becomes completely hidden from view from anywhere on Earth for about a day (unless there’s a solar eclipse, as there was in April).

The moon will return to shine as a crescent in the western evening sky from Saturday onward. If you have an unobstructed view towards the northwest, you might catch sight of its barely-there, 1.4%-illuminated crescent perched above the bright planet Venus after sunset on Saturday. Don’t use binoculars to search until the sun has completely set. Venus will set next, leaving the moon to follow about half an hour later. As the sky is darkening, watch for Mercury a slim fist’s diameter to the upper left (or 9.5° to the celestial southeast) of the moon.

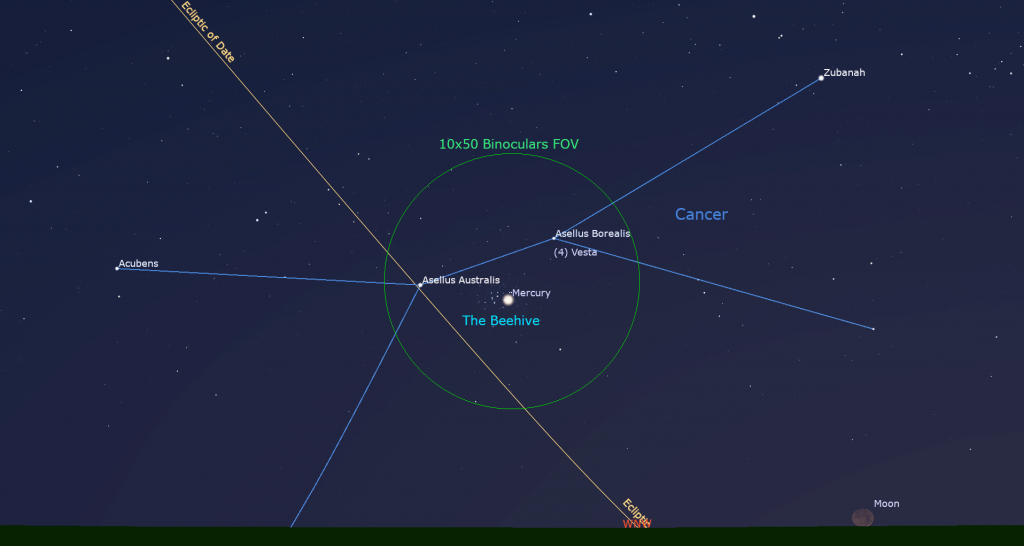

The crescent moon will be easier to see low in the west-northwestern sky as the sky is darkening after sunset next Sunday, July 7. The dot of Mercury will be positioned a generous thumb’s width below (or 2.5 degrees to the celestial southwest) of the moon – easily close enough for them to share the view in binoculars. Mercury and the moon will be in Cancer (the Crab). Mercury will be doing something else, too. Read on…

The Planets

As I mentioned above, the inner planets Venus and Mercury will both be lurking above the northwestern horizon after sunset this week. Venus will set about 30 minutes after the sun. Mercury will linger for almost an hour longer. They’ll emerge into clearer view in the coming weeks. For now, you’ll see them more easily from the tropics. The young crescent moon will shine above each of them on the coming weekend. I shared a lot of detailed information about Mercury last week here.

Mercury will do something noteworthy on Saturday. For a short period after dusk on Saturday, July 6, skywatchers can use binoculars and backyard telescopes to look for the prominent dot of Mercury shining amidst the scattered stars of Messier 44, also known as the Beehive Star Cluster. The cluster, which covers an area of sky double the moon’s, is often visited by the moon and planets because of its location only 1.3 degrees north of the ecliptic. Speedy Mercury will appear just to the lower right (or celestial west of) the cluster on Friday, amid the stars on Saturday, and then to the upper left of them on Sunday. Observers located near the tropics, where the ecliptic stands upright after sunset, will see Mercury’s crossing more easily. As a bonus, the magnitude 8, main belt asteroid Vesta will be travelling with Mercury, but offset to the upper right of the cluster.

At long last we have an easy planet to see in the evening sky – well, kind of…

For everyone at the latitude of Toronto, Saturn will start to rise before midnight on Friday – ending a lengthy evening-planet drought! Due to Earth’s motion around the sun, the stars and distant planets rise 4 minutes earlier each day – so we’ll be able to enjoy late-evening views of Saturn in a few weeks. Saturn will shine during evenings worldwide until next February, so you can go ahead and invest in that telescope you’ve been wanting.

Saturn will spend the next 10 months among the stars of eastern Aquarius (the Water-Bearer). Binoculars will show you an up-down row of five stars to Saturn’s right (or celestial west). A trio of blue-white stars huddling to Saturn’s lower right are named Psi1,2,3 Aquarii (or ψ1,2,3 Aqr). Several golden-coloured stars, including Phi and Chi Aquarii are spread out above them, to Saturn’s right. Hey – the stars are interesting, too!

Saturn’s rings, which will effectively disappear when they become edge-on to Earth next March, already look very narrow against the planet’s globe. Good binoculars can hint at Saturn’s rings, and any telescope will show them to you. For telescope-owners, Earth’s perspective of the Saturn system this year and next will cause its moons to align in the plane of the rings and produce frequent transits of Saturn’s moons and their black shadows across its disk. Dione’s tiny shadow will cross Saturn’s southern hemisphere on Monday night between 11:13 pm and 2 am EDT (or 03:13 to 06:00 GMT on Tuesday).

Today (Sunday, June 30), Saturn will cease its regular eastward motion through the distant stars of Aquarius and begin a retrograde loop that will last until mid-November. The apparent reversal in Saturn’s motion is an effect of parallax produced when Earth, on a faster orbit, passes the ringed planet on the “inside track”. You can observe the planet’s motion by noting how Saturn’s distance from the bright star to its right named Hydor (aka Lambda Aquarii) varies over the coming weeks. Planets are brighter and shine at convenient times during their retrograde periods.

Neptune will rise about 25 minutes after Saturn and follow it across the sky every night. It will commence its own retrograde loop on Wednesday. The remote, blue planet will spend this year in western Pisces (the Fishes), a generous fist’s width to the lower left (or 11° to the celestial ENE) of Saturn. Neptune will also be located a bit more than a thumb’s width to the upper left (or 2° north) of a medium-bright star named 27 Piscium, allowing them to share the view in binoculars. Other less-brilliant stars nearby named 29 Piscium, 24 Piscium, and 20 Piscium will help guide you to Neptune with a backyard telescope or good, strong binoculars. For now, you’ll need to look at Neptune while it’s higher and the sky is dark between about 2 and 4 am local time – but that timing will advance by 30 minutes per week.

Reddish Mars will rise by 2:30 am local time and remain in sight until dawn. If you head out while the sky is still dark, the brightest stars of Aries (the Ram) will twinkle above it. Mars will appear to be a little brighter than Saturn. In a telescope, Mars will display a small, ruddy disk. Its position on the far side of the sun from Earth will keep the planet looking small until later this year. While everything else rises earlier each week as the sky shifts west due to Earth’s motion around the sun, Mars is traveling in the other direction, like a fish holding its location in a moving river. That’s why Mars isn’t yet rising much earlier. It also means that Jupiter, the Pleiades, and the prominent stars of Taurus (the Bull) are being carried towards Mars, setting up those nice photo ops I mentioned above.

Although Uranus will rise next, at about 2:50 am, it won’t climb high enough to deliver clear views in a telescope before the brightening sky overwhelms it. To aid in your search, seek out the pretty, prominent Pleiades star cluster in your binoculars. Uranus will be positioned a palm’s width to its right. They’ll join the evening sky in September.

I already mentioned above that Jupiter is visible in the eastern pre-dawn sky. It will become higher every day. For now, it will clear the trees in the east around 4:30 am local time, as the sky starts to brighten. I’ll start to highlight Jupiter events in a week or two. For now, enjoy its meet-up with the moon and Aldebaran.

On Friday evening, July 5, the dwarf planet Ceres will reach opposition, its closest approach to Earth for the year – a distance of 282.2 million km or 15.7 light-minutes. On the nights around opposition, this largest resident of the main asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter will shine with a peak visual magnitude of 7.4, which is within reach of binoculars and backyard telescopes. Ceres will be located to the lower left of the Teapot-shaped asterism in Sagittarius (the Archer). This week, it will cross about one quarter of the way from the bright star Ascella to Tau Sagittarii (aka Namalsadirah II). Ceres will ascend the southeastern sky after dusk, and then reach its highest elevation, and peak visibility, when due south around 2 a.m. local time. It will spend the rest of July travelling west through the Teapot.

Hercules on High

Moonless nights are ideal for viewing the sky’s best sights. On the next clear evening, head outside after dusk and point your finger directly overhead. That’s the zenith. While objects occupy that position, they always appear at their best because you are looking through the least amount of intervening air. The stars near the zenith barely twinkle for that reason. During late evening in July every year, the constellation of Hercules (the Hero) sits high in the southern sky, just below the zenith. And it contains some of the summer season’s best celestial “tourist attractions”!

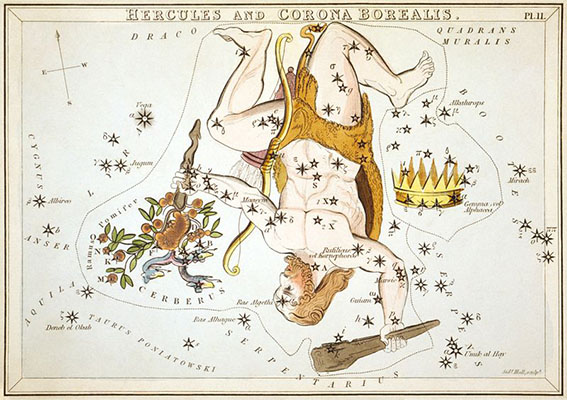

Hercules’ stars aren’t overly bright, but you can still find it very easily, even from mildly light-polluted skies. Face southeast and look for a very bright, white star sitting fairly high in the sky. That’s Vega, the brightest star in Lyra (the Harp) and also brightest in the summer night sky. Another prominent star, orange-tinted Arcturus, will be shining lower than Vega and towards the west-southwest. Between these two stellar signposts is the realm of mighty Hercules.

Hercules’ body is defined by a very recognizable keystone-shaped quartet of medium-bright stars. The keystone asterism is about 6° across (a palm’s width), with its wide end toward celestial north (upwards if you face south) and its narrow end pointed southwards (down). The hero of mythology is standing on his head for Northern Hemisphere observers. His sharply bent legs extend upwards (celestial north), and his two arms are outstretched downward (celestial south). The star that marks his eastern hand, named Maasym, or Lambda Herculis (λ Her), is to the lower left of the keystone. It connects to four other stars to form a loose chain of five stars running left-right, each separated by a couple of finger widths. In classical drawings of Hercules he is grasping the three-headed dog Cerberus, which he was tasked with capturing as one of his twelve labours. In other pictures, the chain of stars forms his arm, and fainter stars in southeastern Hercules are items he is grasping, such as a bough bearing the golden apples of the Hesperides or the two-headed dog Cerberus.

By the way, Hercules’ labours included slaying and skinning the Nemean Lion, killing the Lernaean Hydra, and capturing the Cretan Bull. Those three critters could be represented by the constellations Leo, Hydra, and Taurus – but only Leo (the Lion) shares the summer evening sky with Hercules. Taurus (the Bull) is setting in the west as Hercules climbs the eastern sky in springtime, with Hydra (the Snake) lurking below and between those two figures. In another story, the goddess Hera sent a crab to distract Hercules while he grappled with the Hydra. The crustacean was dispatched and became Cancer (the Crab). In Hercules’ 11th labour, he was to steal the golden apples from the garden of the Hesperides, which were guarded by the hundred-headed Hesperian Dragon. That slain beast accompanies Hercules as the stars of Draco (the Dragon), his celestial neighbor to the north.

Hercules is the fifth largest constellation by area, and was one of the original 48 constellations tabulated in the Almagest, an early astronomy book produced in ancient Greece by Claudius Ptolemaeus (or Ptolemy). The early Greeks depicted Hercules, with his legs bent – as “The Kneeler” praying to his father Zeus to aid him in an upcoming battle. Beyond his feet, high in the northern sky, are the stars of Draco (the Dragon), ready to be crushed underfoot. To the lower right (or celestial west) of Hercules is the little circlet of stars that form the distinctive constellation of Corona Borealis (the Northern Crown). Arcturus sparkles even further off in the same direction.

Hercules’ location 30 degrees north of the celestial equator has allowed its stars to be seen everywhere on Earth except the southern tip of South America and Antarctica. Other cultures have formed patterns with the same stars. The indigenous Lokono or Arawak people of northern coastal South America call these stars Katarokoya (the Spirit of the Green Sea Turtle). The Ojibwe of North America used some of Hercules’ stars to form Noondeshin Bemaadizid (the Exhausted Bather) next to Madoodiswan (the Sweat Lodge), the stars of Corona Borealis.

Let’s tour Hercules. Starting in the keystone, the right-most and brightest star is designated Zeta Herculis (or ζ Her for short). The Stellarium app labels it Rutilicus. This is a binary star system situated about 35 light-years away from us, where the pair of stars orbit around one another. Both stars are yellow sun-like stars, although the brighter star is more massive and luminous. Moving clockwise and left, we arrive at the somewhat dimmer white star Epsilon Herculis (ε Her). Next, a palm’s width above Epsilon, is Pi Herculis (π Her), a cool, giant, orange-tinted star situated about ten times farther away from us than Zeta. At the upper right (celestial northwestern) corner of the keystone sits Eta Herculis (η Her). It is a yellowish, sun-like star, about ten times the diameter of the sun, but a bit cooler than our sun.

Hercules contains quite a few double and binary stars that are visible in a backyard telescope. One of the nicest ones is Rasalgethi, or Ras Algethi “Head of the Kneeler”. That medium-bright star is located about 1.6 fist diameters below (or 16° to the celestial southwest) of Epsilon Herculis, near the border with Ophiuchus (the Serpent-Bearer). Ophiuchus’ bright star Rasalhague sits a slim palm’s width to the left (east) of Rasalgethi. In a small telescope, Rasalgethi easily splits into a lovely pair of orange and greenish stars. The slightly brighter one is a red giant star that varies in brightness randomly over months to years. The fainter companion is a yellow, sun-like star that is itself a binary star too tightly spaced to resolve with a telescope. The stars are about 360 light-years away and are orbiting one another with a period of 3,600 years. This double star, like many others, was given a single name centuries before telescopes revealed that there was more than one star there.

The brightest star in Hercules, Kornephoros “Club-bearer”, sits a fist’s diameter below the keystone, where Hercules’ elbow would be. Only about two finger widths to the lower right (or 3° to the southwest) of Kornephoros is the double star Gamma Herculis (γ Her), sometimes named Nasak Shamiya III. It is another pair of stars that easily splits into two yellow stars when viewed in a backyard telescope. But this duo is a line-of-sight double star. The fainter star is actually much closer to us! Marsic or Marfik, which means “the Elbow” (even though it’s located at the end of Hercules’ western arm) is another “line of sight” double star that’s easy to view in a small telescope. Look for it about four finger widths to the lower right of Gamma.

Hercules’ legs are both bent. Look almost a fist’s diameter to the left (or 8° to the celestial east) of Eta Herculis to spot Theta Herculis, an aging orange giant star at the great distance of 750 light-years. Our hero’s eastern toes are marked by Iota Herculis, a blue-white star that shines about a fist’s diameter to the upper right of Theta. You can also find it by tripling the left side of the keystone. In 10,000 BCE, Iota was Earth’s pole star, and it will do so again around the year 15,500 AD!

Hercules’ more northerly, western knee is marked by blue-white Tau Herculis. It’s traditional Arabic name, Rukbalgethi Shemali means “Northern Knee”. It, too, will take a turn acting as Earth’s pole star in 18,400 AD. It is located almost a fist’s width to the upper right of Eta Herculis. The fainter star Sigma Herculis shines at the halfway mark to Tau. Hercules’ western shin and foot are the stars Phi and Chi Herculis, located to the lower right (celestial southwest) of Tau.

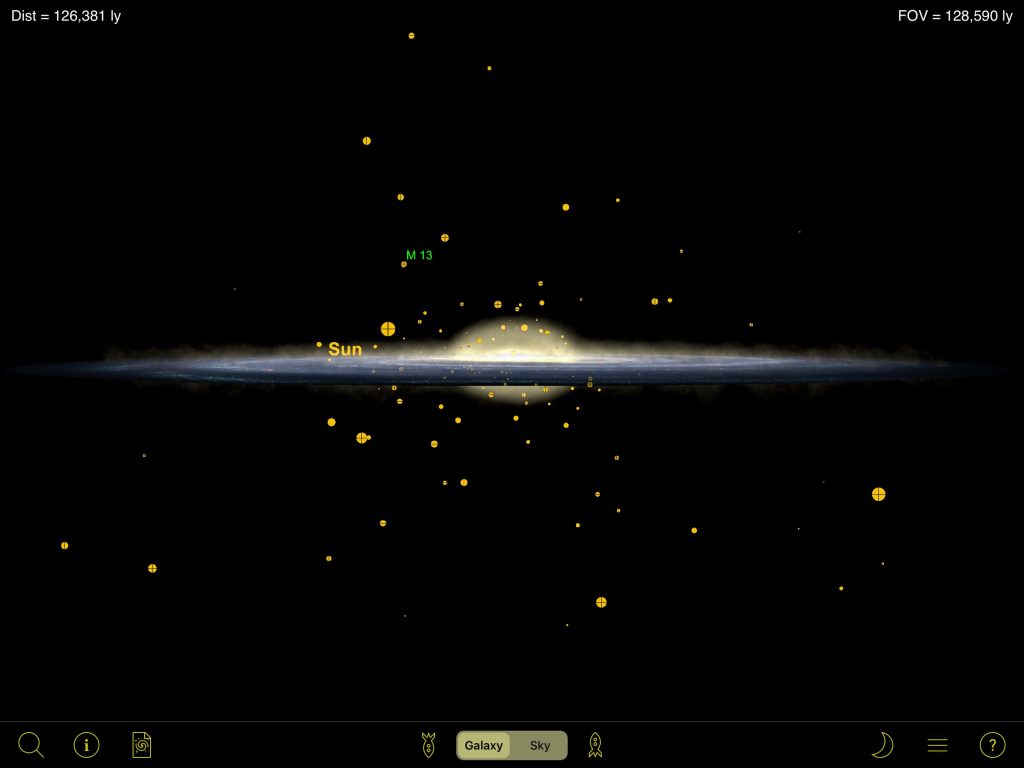

Except for his unremarkable southeastern section, Hercules is positioned away from the summer Milky Way, so it isn’t as rich in deep sky objects as next-door Ophiuchus, Aquila (the Eagle), or Cygnus (the Swan). But it does contain one of my favorite objects and a real summer crowd-pleaser, a globular star cluster known as the Great Hercules Cluster or Messier 13 (or M13). This object is a tightly packed ball of at least 300,000 old stars. At magnitude 5.9, it is visible with unaided eyes under dark skies as a faint smudge, but reveals much more under magnification! It is located along the western (right-hand) edge of the keystone, about one-third of the way from the wide end. Your binoculars should pick it up if the sky is fully dark. Midway between Hercules’ knees there is another, smaller globular cluster called Messier 92. This one is also readily visible in binoculars. A third, small and faint globular cluster designated NGC 6229 sits 6.5°, or a palm’s diameter, to the upper right of M92.

Globular clusters are one of the most interesting classes of objects for stargazers. These spherical concentrations of old, densely packed stars orbit in the region just outside our Milky Way galaxy, and we’ve observed many of them around other galaxies, such as the Andromeda Galaxy. Some of the clusters plunge through the disk of our galaxy from time to time. Viewed in a telescope under dark skies, they will look like a pile of salt poured onto black velvet – with a dense white center surrounded by a sprinkling of outlying stars. Each cluster looks different, varying in the density of stars from core to edge. Photographs reveal that these objects contain a mixture of reddish, blue, and yellow stars in different proportions.

The Great Hercules Globular Cluster was first observed by British astronomer Edmund Halley in 1714 and later included as number thirteen in Charles Messier’s famous list of “not-a-comet” objects. At 21,500 light-years away, it is a relatively close member of that class of objects. It shines with a relatively bright magnitude of 5.8, and it actually covers an area of sky spanning 20 arc-minutes (or two thirds of the moon’s diameter)!

More than 150 of these clusters have been mapped around our galaxy. They are so densely packed that the stars in their interiors are extremely close together, stirring the imagination of those contemplating extraterrestrial intelligent life. Advanced civilizations on planets around stars embedded deep inside a globular cluster would be able to exchange radio messages on timescales of weeks or months – and travel between adjacent solar systems would not require the decades or centuries we would need to visit our nearest neighbours. In fact, M13 was also one of the first targets for potential contact with other civilizations, when a radio message was beamed there from the Arecibo Radio Observatory in 1974.

The stars of Hercules are host to at least fifteen known exoplanets, including one named TrES-4. At 1.7 times the mass of Jupiter, it’s one of the most massive exoplanets yet discovered. However, its calculated density is extremely low, about the same as cork! This is one of the hot-Jupiter class of exoplanets, with a surface temperature in excess of 2,000 C.

If you own a large telescope, watch for the oval of the spiral galaxy named NGC 6207 positioned just 0.5 degrees to the north-northeast of M13. I also suggest looking at the small and very star-like, oval, blue coloured Turtle Nebula (or NGC 6210). It is a planetary nebula located 4 degrees NE of the star Kornephoros – in the direction of the star 51 Herculis. You could also aim your finderscope 1° more than twice the span between the stars Eta and Epsilon Herculis (i.e., the eastern side of the keystone). An Oxygen-III filter will highlight the nebula by dimming the surrounding stars.

If you are an astroimager or you own a really giant telescope, turn your attention to the sky just north of the midpoint between the 5th magnitude stars Marsic and r Herculis. A rich cluster of remote and faint galaxies are gathered there, including the interacting pair NGC 6050 and IC 1179, collective known as Arp 272. The pair are 450 million light-years from Earth! Prominent galaxies near them include NGC 6047, NGC 6042, and another embracing pair named NGC 6039 and NGC 6040 – to highlight just a few.

Let me know how your exploration of Hercules goes.

Binoculars Season

If you missed my story about stargazing with binoculars, I posted it here.

Public Astronomy-Themed Events

Every Monday evening, York University’s Allan I. Carswell Observatory runs an online star party – broadcasting views from four telescopes/cameras, answering viewer questions, and taking requests! Details are here. They host in-person viewing on the first clear Wednesday night each month. Other Wednesdays they stream views online via the observatory YouTube channel. Details are here.

On Sunday, June 30 from 12:30 to 1 pm EDT, head to the David Dunlap Observatory for in-person DDO Sun Fun. Safely observe the sun with RASC Toronto astronomers! During the session, which is for ages 5 and up and runs rain or shine, a DDO Astronomer will answer your questions about our closest star – the sun! Registrants will learn how the sun works and how it affects our home planet, view the sun through solar telescopes, weather permitting, and visit the giant 74” telescope. More information is here and the registration link is at ActiveRH.

On Wednesday evening, July 3 at 7:30 pm EDT, the RASC Toronto Centre will host their free, public Recreational Astronomy Night Meeting, live streamed at https://www.youtube.com/rasctoronto/live. Talks will include The Sky This Month and a trip to the Atacama Desert. Details are here.

Keep your eyes on the skies! I love getting questions and requests. Send me some!