Morning Moon with Planets, a Spotted Saturn, and Starry Nights with Smoke and Meteors!

The Astrospheric app forest fire smoke distribution map across North America for Sunday night, July 28, 2024. Purple and red indicate the most severe smoke loading in the sky overhead. Many weather forecasts will predict clear, cloudless skies – but observers and imagers will find the fainter celestial objects significantly dimmed. I highly recommend the Astrospheric app for planning your astronomy, or visit their browser version at www.astrospheric.com

Greetings, August Stargazers!

Here are your Astronomy Skylights for the week of July 28th, 2024 by Chris Vaughan. Feel free to pass this along to your friends and send me your comments, questions, and suggested topics. You can also follow me on Twitter as @astrogeoguy! Unless otherwise noted, all times are expressed in Eastern Time. To subscribe to these emails please click this MailChimp link.

If you’d like me to bring my Digital Starlab portable inflatable planetarium to your school or other daytime or evening event in Simcoe, Grey, and Bruce Counties, or deliver a virtual session anywhere, contact me through AstroGeo.ca, and we’ll tour the Universe, or the Earth’s interior, together! My book with John A. Read entitled 110 Things to See With a Telescope is a guide to viewing the deep sky objects in the Messier List – for both beginners and seasoned astronomers. DM me to order a signed copy!

The waning moon’s move to the morning sky will provide dark evenings and summer stars this week – so I tour you through Aquila, the Eagle. The moon will pose prettily with planets and the Pleiades in the pre-dawn. Meanwhile, I describe how forest fire smoke across North America is affecting the night sky, highlight two meteor showers, Saturn’s moons crossing its globe, and the inner planets after sunset. Read on for your Skylights!

Southern Delta Aquariids Meteor Shower

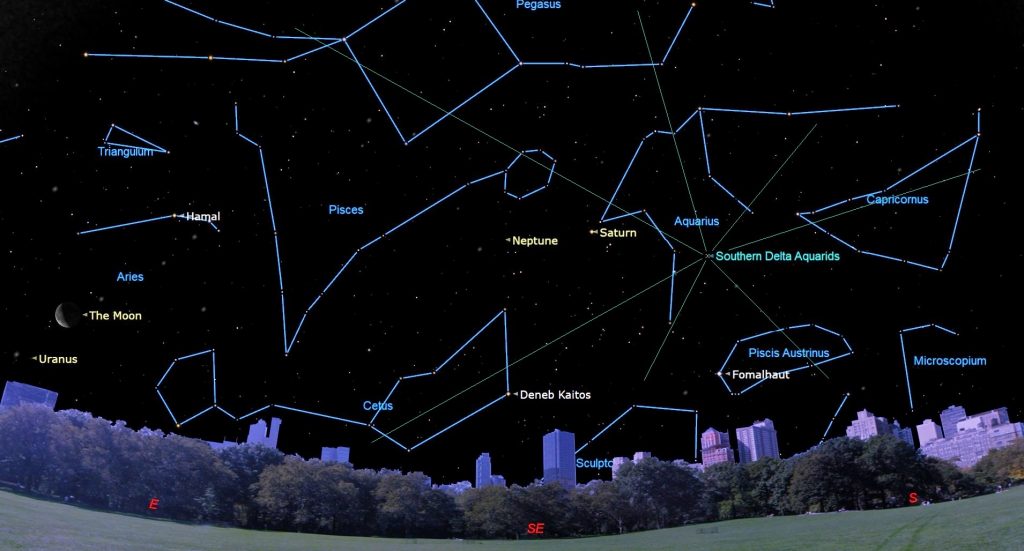

The annual Southern Delta Aquariids meteor shower runs from July 18 to August 21. The shower will peak overnight tonight (Sunday, July 28-29), but it is especially active for a week, so you can keep an eye out for its meteors on the next several nights. This shower, which is probably produced by debris dropped from periodic comet, most likely Comet 96P/Machholz, commonly generates 15-20 meteors per hour during the peak.

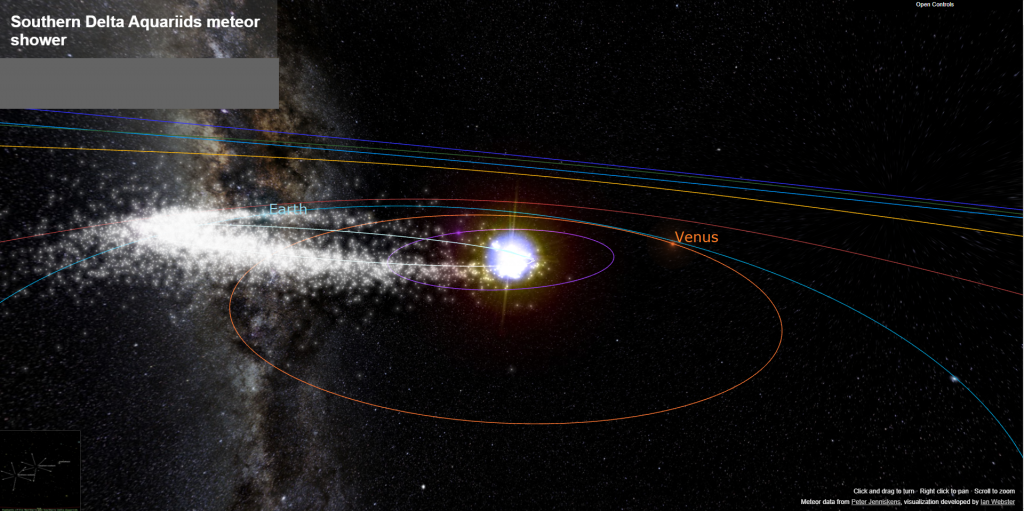

Meteor showers are events that re-occur on the same dates every year when the Earth’s orbit carries us through zones of small particles left behind by multiple passes of periodic comets. (My favourite analogy is the material tossed out of a dump truck as it rattles along. The roadway gets pretty dirty if the truck drives the same route a number of times!) Over time, the dust-sized and sand-sized (and sometimes larger) particles accumulate and spread out into an elliptical “necklace” or “bent pool noodle” in interplanetary space.

When the Earth crosses through the cloud, the particles are caught by our gravity and burn up as they fall through our atmosphere at speeds on the order of 200,000 km/hr. The friction caused by grains moving that quickly through the air generates intense heat that ionizes the air – producing the long glowing trails we see. The duration of a meteor shower depends on the width of the particle cloud – and therefore how long Earth takes to pass through it. The shower’s intensity depends on the type of particles in it, and on whether we pass through the densest portion, or merely skirt the edges.

Not surprisingly, a shower’s performance can vary from year to year because the orbital geometry varies a little and the ring of debris itself orbits the sun. Meteors showers can also be spoiled by moonlight. Fortunately, the 37%-illuminated crescent moon will not clear the treetops until about 1 am local time tonight, leaving the late evening sky nice and dark around the world.

The nickname for meteors is “shooting stars” or “falling stars”, but they bear no physical connection to the distant stars. The action is taking place 100-200 km over your head and within Earth’s blanket of atmosphere. All of your favourite constellations will look the same as ever at the end of the shower!

The meteors from a particular shower can appear anywhere in the night sky, and they will appear to be travelling away from a location in the sky called the radiant. The Southern Delta Aquariids meteor shower’s radiant is located in Aquarius (the Water-Bearer) – hence the name. This year, the bright planet Saturn will be shining about 1.5 fist diameters to the right (celestial west) of the radiant – offering us a nice reference location. The Southern Delta Aquariids radiant will rise above the southeastern horizon in late evening and climb to a third of the way up the southern sky around 3:30 am local time. Meteor showers are most active in the hours before dawn because that’s the time when the sky overhead is plowing directly into the oncoming debris field, like bugs hitting a moving car’s windshield. When the radiant is highest, more of the sky is available for meteors. When it’s low, many of the meteors are hidden below the horizon. This one is even better from the southern tropics, where Aquarius climbs almost overhead in the sky.

To see the most meteors during any shower, try to find a safe, ideally rural, viewing location with as much open sky as possible. If you can hide bright lights behind a building or tree, that will help. You can start watching as soon as the sky becomes dark. That’s also a good time to catch the rarer, very long meteors produced by particles skipping across the Earth’s upper atmosphere. Don’t worry about watching the radiant. Meteors in that part of the sky will be heading directly towards you and will have very short trails. Instead, try to track the meteors’ paths backwards to find their radiant.

Bring a blanket for warmth and a chaise to avoid neck strain, plus snacks and drinks. Try to keep watching the sky even while chatting with friends or family – they’ll understand. Call out when you see one; a bit of friendly competition is fun!

Avoid looking at your phone or tablet since its bright screen will spoil your dark adaptation. If you must use a mobile device, turn the brightness down, or cover the screen with red film. Disabling app notifications will reduce the chances of unexpected bright light, too. And remember that the narrow fields of view that binoculars and telescopes deliver will not help you see meteors. Good luck!

The prolific Perseids meteor shower, which runs annually between July 17 and August 26, has begun, too! That shower will peak on August 11-12. Its meteors will be travelling away from the northeastern sky.

Smoky Skies

Wildfires are raging across North America. The prevailing northwesterly winds have been carrying heavy smoke across my location in southern Ontario. The question is – if the days are sunny and the nights cloud-free, can we observe despite the smoke?

Airborne particulate matter (or PM) includes aerosols and both natural and industrial organic and metallic compounds. Particles with diameters of 10 micrometres or smaller arising from construction, energy production and waste combustion, wind-blown dust and pollen, and wildfires can all be of concern in high concentrations. Those are referred to as PM10. For human health and safety, fine inhalable particles with diameters smaller than 2.5 micrometres, or PM2.5, are tracked. Here is the link to the USA Fire and Smoke map https://fire.airnow.gov/ which covers all of North America. Fire symbols show the fires and colour-coded dots indicate the air quality index (AQI) over cities. Grey shading shows the current smoke distribution. Click any dot to view the air quality and plot a graph of recent history.

Fine particulate matter, including smoke, can severely reduce the transparency of the atmosphere. A heavy soot load will significantly obscure views of deep sky objects, especially galaxies and nebulae. The brightest open star clusters and brighter globular clusters may still be visible in binoculars or a telescope, depending on the severity of the contamination. Bright double stars, the moon, and the bright planets remain visible, but their fainter features, such as the moons of Saturn and fine details on the moon, may not be. Meteor showers will also be impaired.

Good astronomy weather forecasting apps also track and predict smoke conditions. Before planning your observing session or heading to a remote site with your telescope, be sure to check both the clouds and the smoke. The sky transparency (the second row of hourly boxes) on www.Astrospheric.com is coloured white or pale blue when the sky is poor and dark blue when it is good for viewing. (Regular clouds make the boxes white, too.) The map at the top of the screen has buttons to display various layers, including a flame icon for smoke (red is severe, grey is clear). Any of those data sets can be run forward in time.

A final thought. Smoke soot (and spring pollen, for that matter) can coat your optics. Put the caps on your glass surfaces when not viewing and consider cleaning them after exposure to contaminants.

The Moon

For stargazers worldwide, this will be the darkest week of the current lunar month. Earth’s natural nightlight will be rising after midnight and approaching the morning sun. For about the first half of this week, the moon’s pale form will also be visible in the bright morning sky. After that it will be too slim and too close to the sun to be seen after sunrise.

Tonight (Sunday) the waning crescent moon will rise with the stars of Aries (the Ram) around 12:30 am local time. Night owls across Canada and the northern USA might notice that the moon is tinted brown by the forest fire smoke spreading across the continent. For the second time this month, the waning crescent moon will join Uranus and the bright Pleiades star cluster in the eastern sky during the wee hours of Monday morning. Uranus will be positioned a slim palm’s width below the moon, allowing it to be found in binoculars using the moon as a reference. The Pleiades will be positioned a little farther to the moon’s lower left (or celestial east). By about 3 am local time, the bright planets Mars and Jupiter will rise high enough to join the party.

After 24 hours of additional eastward orbital motion, the crescent moon will shift into Taurus (the Bull) and shine above Mars and Jupiter in the eastern sky from the wee hours until sunrise, making a fine photo opportunity. The moon and Mars will be just close enough to share the view in binoculars. The grouping will be bracketed above and below by the Pleiades and the bright red star Aldebaran, respectively.

The pretty moon will still be near those planets on Wednesday morning. Take another picture before the sky brightens too much! The moon will begin August in Gemini (the Twins). Early risers on Friday morning can look a palm’s width to the left (or celestial northeast) of the moon for Gemini’s brightest stars Pollux and Castor. Skywatchers in more westerly time zones will see the moon a little closer to Pollux, the lower, brighter, and more golden of the two stars.

For most folks, Friday will be their last easy view of the moon in the morning. Its extremely thin crescent will also appear just above the eastern horizon before sunrise on Saturday. On next Sunday, August 4 at 7:13 am EDT, 4:13 am PDT, or 11:13 Greenwich Mean Time, the moon will officially reach its new moon phase while in Cancer (the Crab) and 3.9 degrees north of the sun. While new, the moon is travelling in the space between Earth and the sun. Since sunlight can only illuminate the far side of the moon, and the moon is in the same region of the sky as the bright sun, it becomes completely hidden from view from anywhere on Earth for about a day (unless there’s a solar eclipse). In this case, sharp-eyed observers might catch sight of the very slender young crescent moon above the western horizon near bright Venus next Sunday after sunset.

The Planets

Speaking the Venus, our hot sister planet will be following the sun down in evening this week. If your western horizon is unobstructed and free of cloud or haze, you can start to look for Venus’ very bright dot as the sky darkens, especially after about 9 pm local time at mid-northern latitudes. The planet should be less than a palm’s width above the horizon. You’ll need to wait until the sun has fully set to use binoculars. Don’t worry if you miss it, though – Venus will be our brilliant “Evening Star”, gleaming high in the western sky throughout fall and winter.

Mercury, the other inner planet, has also been shining in the western sky after sunset. It is returning to the sun now, causing it to shift lower in the sky from night to night. For the early part of this week, you’ll find Mercury, currently about 50 times fainter than Venus, positioned about a fist’s width to Venus’ left (or celestial southeast) – and lower each day.

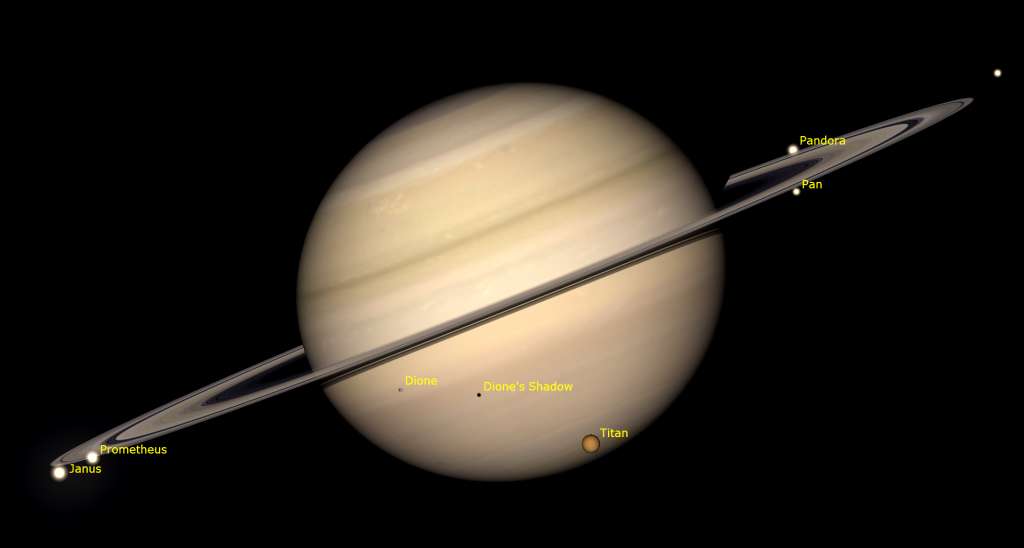

The ringed planet Saturn will be rising by about 10:30 pm local time this week, and half an hour earlier with each passing week – so we’re into prime Saturn-viewing time. Saturn will spend the next 10 months among the modestly-bright stars of eastern Aquarius (the Water-Bearer). Saturn’s rings, which will effectively disappear when they become edge-on to Earth next March, already look very narrow against the planet’s globe. Good binoculars can hint that Saturn has rings, and any size of telescope will show them to you. Earth’s perspective of the Saturn system this year and next year will cause its moons to align in the plane of the rings and produce frequent transits of Saturn’s moons and their black shadows across its disk. But you’ll need a high quality telescope to watch those. For observers in the Americas, Saturn’s largest moon Titan will cross the south polar region of Saturn’s globe on Thursday morning, August 1 from 1:12 to 3:48 am EDT. The tiny moon Dione and its own shadow will cross closer to the ring plane in the same interval.

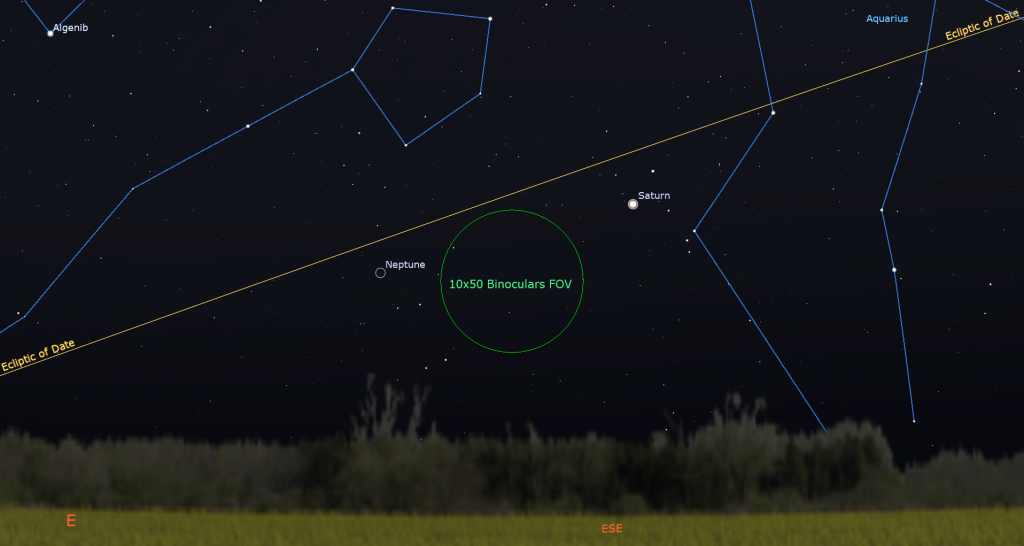

Neptune will rise about 20 minutes after Saturn and chase it across the sky every night. The remote, blue planet will be spending this year in western Pisces (the Fishes), a fist’s width to the lower left (or 11° to the celestial ENE) of Saturn. Neptune will also be located a bit more than a thumb’s width to the upper left (or 2° north) of a medium-bright star named 27 Piscium, allowing them to share the view in binoculars. Other less-brilliant stars nearby named 29 Piscium, 24 Piscium, and 20 Piscium will help guide you to Neptune with a backyard telescope or good, strong binoculars. For now, you’ll need to look at Neptune while it’s higher up and the sky is dark – between about 1 and 4:30 am local time.

The rest of the planets will rise within Taurus (the Bull) during the wee hours, and then remain in sight until dawn. (They, too, will eventually migrate into the evening sky.) Uranus will lead the way. After it rises around 1 am local time, the magnitude 5.8 planet will be visible in binoculars and a backyard telescope as a dull, non-twinkling, blue-green star. Uranus will be cruising about a palm’s width from the Pleiades star cluster all year. At the moment, the planet is almost a palm’s width to the lower right of those stars.

The reddish, medium-bright planet Mars will clear the rooftops to the east by about 2:30 am local time and then remain in sight until almost sunrise, when it will appear partway up the eastern sky. Mars’ eastward orbital motion has been almost enough to hold the planet in place while everything else shifts west each day due to Earth’s motion around the sun. As a consequence, Mars has been racing by the other planets. This week it will travel right-to-left (or west-to-east) above the Hyades Cluster, the stars that form the triangular face of the bull. Mars is heading for a tight conjunction with Jupiter on August 15. Mark your calendars!

If you head outside while the sky is still dark, the brightest stars of Aries (the Ram) and Perseus (the Hero) will twinkle well above Mars. In a telescope, Mars will display a small, rusty-coloured disk. Its position on the far side of the sun from Earth is keeping the planet looking small until later this year. If you do check it out, take notice that Mars is only 89%-illuminated because its angle from the sun is 62°. (When objects are about 90° away from the sun, they show a half-moon shape. Only when they are opposite the sun in the sky are planets fully illuminated.)

Oops – I buried the lead a little. It will be Jupiter that draws your attention first once it clears the rooftops around 3 am local time this week. The giant planet is now well and truly dominating the eastern sky until sunrise. Mars will shine to Jupiter’s upper right. Over this week, their separation will decrease from 8° to 5° – putting them into the same binoculars field of view.

Binoculars will show Jupiter’s four Galilean moons named Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto lined up beside the planet. Those moons complete orbits of the planet every 1.7, 3.6, 7.2, and 16.7 days, respectively. If you see fewer than four moons, then one or more of them is crossing in front of or behind Jupiter, or hiding in Jupiter’s dark shadow – or two of the moons are very close together or occulting one another. All four of them will huddle to the west of Jupiter on Thursday morning. Even a small, but decent quality telescope can show you Jupiter’s dark belts and light zones, which are aligned parallel to its equator. With a better grade of optics, Jupiter’s Great Red Spot, a cyclonic storm that has raged for hundreds of years, becomes visible for several hours when it crosses the planet every 2nd or 3rd night. For observers in the Americas, that GRS will cross Jupiter’s disk on Tuesday, Thursday, and next Sunday morning. If you have any coloured filters or nebula filters for your telescope, try enhancing the spot with them.

An Eye on the Eagle

Look halfway up the southeastern sky on early August evenings, and you’ll easily spot the bright, white star Altair sitting at the bottom corner of the Summer Triangle asterism. Altair is the brightest star in the ancient constellation of Aquila (the Eagle) and marks the great bird’s head. The eagle’s body and tail extend downwards to the right (or celestial southwest), more or less following the Milky Way. The wings extend upwards and downwards.

The great bird’s location close to the Milky Way has populated it with rich star fields. The celestial equator passes through it – allowing it to be seen easily by both Northern and Southern Hemisphere skywatchers. On the right (west) it is bordered by Scutum (the Shield), Serpens Cauda (the Snake’s Tail), and Ophiuchus (the Serpent-Bearer). Sagittarius (the Archer) and Capricornus (the Sea-Goat) are below it (south), and cute little Delphinus (the Dolphin) and Sagitta (the Arrow) above (north). A section of Hercules (the Hero) touches the eagle’s northern wingtip. In area, the bird spans three fist diameters square, or 30° by 30°, but the bright stars only cover about 20°, from head to tail and wing tip to tip.

Aquila so clearly resembles a bird that many cultures saw the same pattern in its stars, including the Babylonians. In Greek mythology, it was the eagle that held Zeus’ thunderbolts. The Romans called it Vultur volans “the flying vulture”. The Hindus associated the stars with the half eagle-half human god Garuda.

Classic Chinese poetry told a well-known story about the Weaver Girl and the Cowherd, one of their four great folktales. In the story, Zhī Nǚ (织女) the weaver girl was in love with Niú Láng (牛郎) the cowherd. To prevent their forbidden love, they were banished to the heavens. Zhi Nu, represented by the nearby bright star Vega, and Niu Lan, represented by Altair, were separated by the Silver River, i.e., the Milky Way. The two small stars which are visible just above and below Altair represent their children. As the story goes, each year on the 7th day of the 7th month in the Chinese lunisolar calendar, a flock of magpies would form a bridge, reuniting the lovers for one night only. In some years, the lunisolar calendar begins at the end of January, putting their 7th month into August. I suspect that those magpies were actually Perseids meteors, which travel parallel to the Milky Way every August.

The name Altair arises from the Arabic expression for “flying eagle”. The star itself is warm-white and of spectral class A7Vn, about ten times larger than our sun. It’s a mere 17 light-years away, making it the twelfth brightest star in the night sky worldwide. Altair’s 10-hour rotation rate is one of the fastest known for stars, spinning so rapidly that the star has an oblate shape (wider at the equator than it is tall). In the sky, Altair is symmetrically flanked by two small stars named Alshain and Tarazed, or β and γ Aquilae, respectively. Because the three stars resemble a weighing balance, their names are derived from the Arabic phrase for one: “shahin-i tarazu”. The aborigines of Australia envision the trio as a male spirit and his two wives, or as a young man with feather decorations on his arms.

The trio spans about three finger widths, or 5° of sky. Higher (more northerly) and brighter Tarazed is interesting. This orange, K3II-class star is 395 light-years-away. It is young, but highly evolved – already burning core helium, and it emits almost 3,000 times the luminosity of our sun. It also emits an abundance of X-rays! Magnitude 3.7 Alshain is located two finger widths below (or 2.7° south-southeast of) Altair. This 44.7 light-years-away, yellowish G8IV-class star has also exhausted its core hydrogen and is evolving into a giant star.

The rest of Aquila’s main stars are fainter, but nonetheless visible to unaided eyes under a dark sky. Almost a fist’s diameter to the lower right (southwest) of Altair is the star Delta Aquilae, or Almizan I, representing the eagle’s body. The wings, each a generous fist’s diameter (11°) in length, extend up and down from that star. The upper wingtip is marked by the white star Deneb al Okab Australis, or Zeta Aquilae, and a slightly dimmer star named Deneb al Okab Borealis. Those names mean the southern and northern “tail of the eagle”. (The reference to the tail arose by using a different interpretation of the star patterns.)

The lower wing is formed by two widely spaced stars. Almizan II is at the elbow, and Almizan III is at the wingtip. (Some apps use the designations Eta Aquilae and Theta Aquilae, respectively.) The eagle’s tail is marked by a pair of small stars separated by a finger’s width. The brighter tail star is named Al Thalimain Prior “the front ostrich”. The Pioneer 11 spacecraft, launched in 1973, is coasting towards this star, with an arrival time in about 4 million years! The “rear ostrich” is the star Al Thalimain Posterior or Iota Aquilae (or i Aql), which sits above and between the tail and the lower wingtip. Those names appear to be left-over from a previous version of the constellation.

A telescope aimed at the star named h Aql that shines a finger’s width above Al Thalimain Prior will split it into a cozy pair – one star orange and the other one purplish. The small star that shines below and between Al Thalimain Prior and iota is a deep red coloured carbon star named V Aquilae.

Almizan II, the lower elbow star, is a Cepheid variable star that doubles in visible brightness from magnitude 3.5 to 4.4 on a 7.18 day cycle. At maximum, it shines almost as brightly as Lambda Aquilae, the tail of the eagle. At minimum, it’s as faint as Iota Aql, the “rear ostrich”. Try comparing the brightness of those three stars on different nights and see the difference!

Sweep your binoculars though the area around and above Aquila to see an abundance of stars from the nearby galactic plane, and a dark dust lane. About three finger widths to the right (or 4° WSW) of the eagle’s tail, in the next-door constellation Scutum (the Shield), you’ll easily spot another avian object – the Wild Duck Cluster or Messier 11 – a famous bright open cluster. My friend and co-author John A. Read calls it the Borg Cube from Star Trek, and I agree!

Within a binoculars’ field of view to the lower right of Okab are two more open star clusters named NGC 6738 and NGC 6709. Another binoculars’ field diameter to their lower right is a bigger, brighter cluster called the Tweedledee Cluster, or Graff’s Cluster.

If you have a large telescope, or if you are observing Aquila under dark, rural skies, aim your telescope a few finger widths along the eagle’s upper wing and look at the round planetary nebula named the Snowglobe or Ghost of the Moon, or NGC 6781. It’s not very bright, but it’s huge – more than twice as large as Jupiter!

Let me know if you enjoy the Eagle!

Public Astronomy-Themed Events

Every Monday evening, York University’s Allan I. Carswell Observatory runs an online star party – broadcasting views from four telescopes/cameras, answering viewer questions, and taking requests! Details are here. They host in-person viewing on the first clear Wednesday night each month. Other Wednesdays they stream views online via the observatory YouTube channel. Details are here.

On Thursday, August 1, starting at 9 pm, U of T’s AstroTour at McLennan Physical Laboratories, 255 Huron Street, will present a free public lecture entitled Pulsar Scintillation: How an Astronomer Learned to Love Clouds. The speaker will be Ashley Stock, a graduate student at the Dunlap Institute of Astrophysics and Astronomy, University of Toronto. The talk will be followed by astronomy demos and telescope tours (weather permitting). Details are at https://www.astro.utoronto.ca/astrotours/#detail.

Space Station Flyovers

The ISS (or International Space Station) will not be visible over the Greater Toronto Area this week.

Keep your eyes on the skies! I love getting questions and requests. Send me some!