Multiple Meteor Showers, Saturn Shines Brightest, and a Trip Through the Triangle and its Zoo!

This gorgeous image of the Dumbbell Nebula, aka Messier 27, in Vulpecula was captured by Steve McKinney of Toronto near Thornbury, Ontario on July 29, 2017. It shows a shell of glowing gas surrounding a hot white dwarf star, the corpse of a star similar in mass to our sun. The image spans about 0.4 degrees of sky. Enjoy more of Steve’s images at https://www.astrobin.com/users/SmackAstro/

Hello, Late-July Stargazers!

Here are your Astronomy Skylights for the week of July 25th, 2021 by Chris Vaughan. Feel free to pass this along to your friends and send me your comments, questions, and suggested topics. You can also follow me on Twitter as @astrogeoguy! Unless otherwise noted, all times are expressed in Eastern Time. To subscribe to these emails please click this MailChimp link.

I can bring my Digital Starlab portable inflatable planetarium to your school or other daytime or evening event, or teach a session online. Contact me through AstroGeo.ca, and we’ll tour the Universe, or the Earth’s interior, together!

This week, the moon will wane towards third quarter, leaving evening skies all around the world darker for stargazers and meteor watchers. I tour you through the best of the Summer Triangle asterism and the animal constellations around it. Venus will gleam after sunset, Mars will brush Regulus, Jupiter will sport shadows, and Saturn will reach peak visibility at week’s end. Read on for your Skylights!

Southern Delta Aquariids Meteor Shower

The Southern Delta Aquariids meteor shower runs annually from July 21 to August 23. It will peak before dawn on Thursday, July 29 – but it is quite active for a week surrounding that date, so you can already keep an eye out for its shooting stars. This shower, produced by debris dropped from periodic Comet 96P/Machholz, commonly generates 15-20 meteors per hour at the peak. It is best enjoyed from the southern tropics, where the shower’s radiant, in southern Aquarius, climbs higher in the sky. Unfortunately, the bright gibbous moon shining in the night-time sky on the peak date will severely reduce the number of meteors seen – so continue your meteor-watching on the following few nights, when the moon will wane and rise later.

The spectacular Perseids meteor shower, which runs annually between July 17 and August 26, has begun, too! That shower will peak during mid-day in the Americas on Thursday, August 12.

Meteors from a particular shower appear to be travelling away from the constellation they are named for. During evening Southern Delta Aquariids will be moving away from a spot low in the southeastern sky, Perseids from low in the northeastern sky. To increase your chances of seeing any meteors, find a dark location with lots of sky, preferably away from light polluted skies, and just look up with your unaided eyes.

Binoculars and telescopes are not useful for meteors because their fields of view are too narrow to fit the streaks of meteor light. Don’t watch the radiant. Any meteors near there will have very short trails because they are travelling towards you. Try not to look at your phone’s bright screen – it’ll ruin your night vision. And keep your eyes heavenward, even while you are chatting with companions. I’ll write more about meteors in the coming weeks. For now, happy hunting!

The Moon

The moon will spend this week rising in the middle of the night and then shining shyly in the morning daytime sky.

Tonight (Sunday) the waning gibbous moon will rise in the east at about 10:30 pm local time – but it will be a while before it climbs high enough to glimpse above buildings and trees. That’s because the ecliptic, the zone along which the sun, moon, and planets travel, arcs very low across the southern sky in July for mid-Northern latitude skywatchers. That low night-time ecliptic is opposite to the very high daytime ecliptic that gives us a high noonday sun.

Sunday night’s moon will be positioned a slim palm’s width below (or 4.75 degrees to the celestial south) of Jupiter in Aquarius (the Water-Bearer), with Saturn off to their right (west) – giving a nice photo opportunity! Those planets also suffer the low-sky problem, but they’ll be rising far earlier a month from now – giving them more time to climb higher before bedtime.

The moon will spend the rest of the week waning in illuminated phase and rising about half an hour later each night. It will depart Aquarius on Tuesday night, traverse the crooked border between Cetus (the Whale) and Pisces (the Fishes), and land in Aries (the Ram) next Sunday morning. When a lunar phase occurs in the first few days of a calendar month, it can repeat at month’s end. For the second time in July, the moon will officially reach its third quarter phase at 9:16 am EDT (or 13:16 Greenwich Mean Time) on Saturday, July 31.

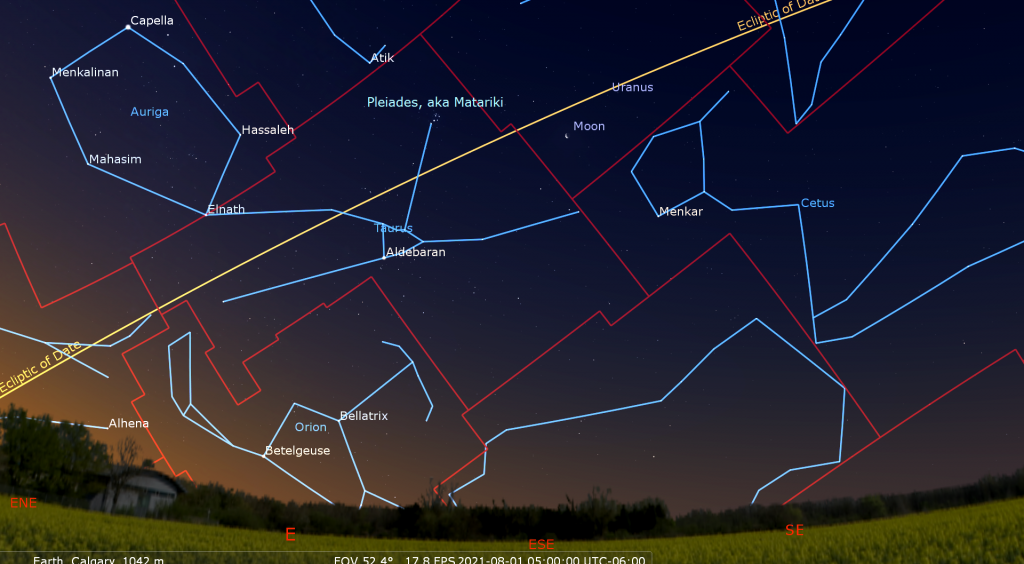

If you are up before dawn on August 1, look for the familiar winter constellations of Taurus (the Bull) and Orion (the Hunter) to the lower left (or celestial east) of the crescent moon. The bright little Pleiades star cluster will be located a generous fist’s diameter to the moon’s left. The return to visibility of the Pleiades (Messier 45) before dawn holds great significance to the Maori and other South Pacific peoples, who call those stars called Matariki. Last Friday’s full moon, the first since Matariki’s return, signalled the start of their traditional new year. I wrote more about that here.

Also on Sunday morning, August 1, the moon will be positioned several finger widths to the lower left (or 4 degrees to the celestial southeast) of the magnitude 5.8 planet Uranus. Early risers in Europe and Africa will see the pair even closer together. While Uranus is readily seen in binoculars, I suggest that you note its location between the stars of Aries and Cetus, and hunt for it on a night when the bright moon has left the scene. Uranus, too, will become an evening planet during August.

The Planets

As the sky begins to darken after about 9 pm local time at mid-northern latitudes this week, Venus will appear amidst the western twilight glow as a bright point of light shining about a fist’s diameter above the western horizon. It will get easier to see as the minutes pass and the sky darkens, then set at about 10:15 pm local time. When viewed in a backyard telescope, 83%-illuminated Venus will exhibit a smallish disk and a somewhat squashed shape. Aim your telescope at Venus as soon as you can spot the planet in the sky (but ensure that the sun has completely disappeared first). That way, Venus will be higher and shining through less distorting atmosphere – giving you a clearer view. Although Venus will be parked in the western sky for the rest of 2021, it won’t climb very high.

Much fainter Mars will pass telescope-close to the bright star Regulus on Thursday evening. Wait until the sun has fully disappeared, and then aim your binoculars or telescope just above the west-northwestern horizon, a slim fist’s diameter to the lower right of Venus. Regulus will be slight brighter than Mars, and will be positioned below (to the celestial south of) the planet.

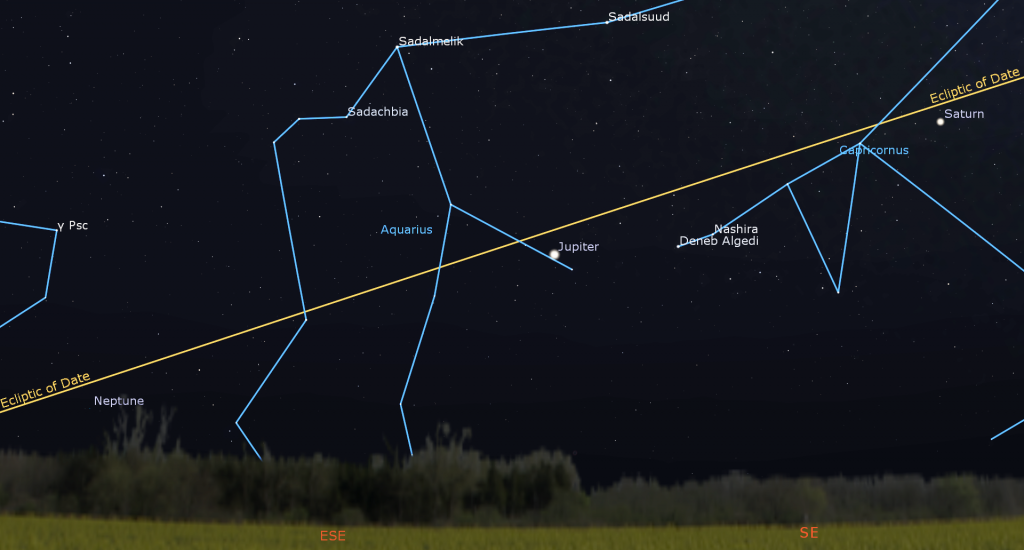

This week, the yellow-tinted dot that is Saturn will rise within the faint stars of central Capricornus (the Sea-Goat) at about 9 pm local time and then it will cross the overnight sky until dawn swallows it up in the southwestern sky. Saturn is being pursued across the sky by 16-times brighter Jupiter, which sits two fist diameters to Saturn’s left (celestial east). Watch for the Milky Way and the teapot-shaped stars of Sagittarius (the Archer) sitting several fist diameters off to Saturn’s right (celestial west).

Next Sunday night (well, 1 am EDT on Monday, August 2 – but close enough) Saturn will reach opposition and peak visibility for 2021! Objects at opposition are visible all night long – rising at sunset and setting at sunrise – because Earth is positioned between them and the sun. At opposition, Saturn will be 1.337 billion km, or 74.3 light-minutes away from Earth, and it will shine at magnitude of 0.18 – its brightest for this year.

In a telescope Saturn will show an apparent disk diameter of 18.6 arc-seconds (less than half that of Jupiter), and its rings will subtend 43.3 arc-seconds (almost as wide as Jupiter). Around opposition Saturn’s rings are brightened by the Seeliger Effect. That’s extra sunlight that is scattered back directly towards us because the sun is “behind us” when we are viewing Saturn. The phenomenon, announced by Hugo von Seeliger in 1887, also brightens Mars at opposition and makes every full moon a little extra bright.

Even a small telescope will show Saturn’s rings and several of its brighter moons – especially its largest moon, Titan! Because Saturn’s axis of rotation is tipped about 27° from its orbital plane (a bit more than Earth’s tilt), we can see the top surface of its rings, and its moons can arrange themselves above, below, or to either side of the planet. During this week, Titan will migrate counter-clockwise around Saturn, moving from below (celestial south) Saturn tonight to the upper right (celestial west) of the planet next Sunday. (Remember that your telescope will probably flip the view around.) Saturn’s rings, which will be narrowing every year until the spring of 2025, are already narrow enough to reveal a bit of Saturn’s southern polar region extending past them.

This week very bright, white Jupiter will rise an hour after Saturn – just before 10 pm local time. The magnitude -2.8 planet will follow Saturn across the sky until sunrise hides them both while they’re over the southwestern horizon. Jupiter has been moving slowly westward across the distant stars of central Aquarius (the Water-Bearer), a parallax effect produced because Earth, on a faster orbit, is passing Jupiter on the “inside track” around the sun.

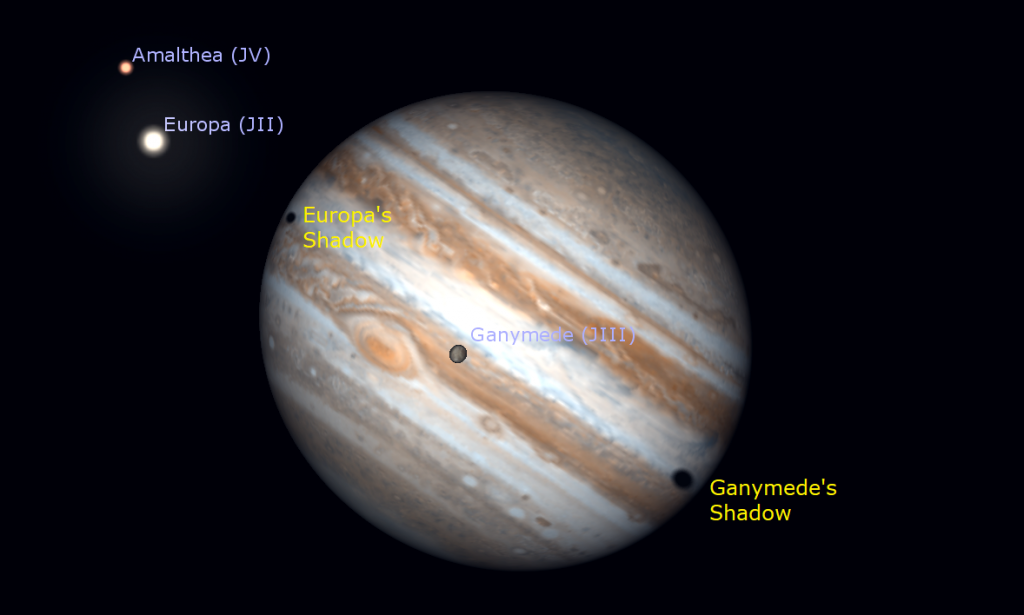

Binoculars and small telescopes will show you Jupiter’s four largest moons, Io, Europa, Callisto, and Genymede – collectively called the Galilean moons. They are always arranged in a straight line through the planet, but their pattern varies from night to night. For observers with good telescopes in the Eastern Time Zone the Great Red Spot (or GRS) will be visible crossing Jupiter starting late on Sunday (July 25), Wednesday, and Friday nights, also before dawn on Wednesday, Friday, and Sunday morning.

From time to time, the small round black shadows cast by Jupiter’s Galilean moons become visible in amateur telescopes when they cross (or transit) the planet’s disk. Io’s small shadow will be visible on Monday morning, August 26 between 3:10 and 5:25 am EDT and again on Tuesday night after Jupiter rises, until about 11:55 pm EDT. Ganymede’s large shadow will be visible on Sunday, August 1 between 2:40 and 6:15 am EDT.

During that same Sunday morning, August 1 event, observers with telescopes in the western half of North America and the Pacific Ocean region can see a rare event on Jupiter! At about 3:30 am Central Daylight Time (or 08:30 GMT) the Great Red Spot will join Ganymede’s shadow while it is still crossing Jupiter’s disk. At 5:08 am CDT or 10:08 GMT, Europa’s smaller shadow will join them, too! About 12 minutes later, Ganymede’s shadow will complete its transit and disappear, leaving the GRS and Europa’s shadow to cross until about 8 am CDT or 13:00 GMT.

Dim, blue Neptune is located near the border between Aquarius and Pisces (the Fishes) – about 2 fist diameters to the lower left (or 23° to the celestial east) of Jupiter. It rises at about 10:45 pm local time and reaches peak visibility halfway up the southern sky at 4 am local time. Magnitude 5.8 Uranus is bright enough to see in binoculars and backyard telescopes, even near cities. This week it will rise at about 12:30 am local time. Hamal and Sheratan, the two brightest stars in Aries (the Ram), will sit above it all summer. The crescent moon will visit it next Sunday morning.

A Summer Triangle Tour

When you are outside on the next clear night, be sure to look for the three bright and beautiful blue-white stars of the Summer Triangle asterism, which shines high in the eastern sky in late July and early August. Once you have it identified, you can find some treasures within it, and follow its progress across the night sky until it finally disappears in late fall.

Find an open area and face east. The very bright star Vega will be almost straight over your head. It’s the fifth brightest star in the entire night sky, and one of the first stars to appear after dusk. Now look for the other two corners of the triangle. Altair, not as bright as Vega, sits about 3.5 outstretched fist diameters to the lower right of it (or 34° to the celestial SSE). The third star, Deneb, is about 2.5 fist diameters to the lower left of Vega (or 24° to the celestial east), and is higher up than Altair. It’s a very big triangle!

Can you see the four fainter stars forming a small, upright parallelogram just below Vega? That shape is about a thumb’s width wide and a few finger widths tall. This box is the body of the musical harp that makes up the constellation of Lyra (the Lyre). Vega marks the top of the instrument’s neck. Vega’s visual magnitude, or brightness, is the zero reference point for the scale we use to define stars’ brightness values. Objects brighter than Vega have values lower than zero, and vice versa. Antares, the bright, reddish star sitting over the southern horizon in Scorpius (the Scorpion), has a value of about 1.0, making it 2.5 times dimmer than Vega. (It’s a logarithmic scale.)

Vega also forms a little triangle with two other dim stars, each about a finger’s width apart. The star to Vega’s upper left is named Epsilon Lyrae, also known as the Double Double. Can you tell it’s actually two stars crammed tightly together? Try using binoculars. When magnified in a telescope, each star splits again!

Deneb marks the tail of great bird Cygnus (the Swan). Look for a modest star sitting about two fist diameters to the right (or 22° to the celestial southwest) of Deneb. That’s Albireo, a colourful double star that marks the swan’s head. (I like to think of Albireo as the centre of Doc Brown’s flux capacitor from Back to the Future. The summer triangle’s stars are the gadget’s corners!) Albireo was given only a single name before telescopes revealed that it included two stars!

A widely spaced string of medium-bright stars aligned up-down traces out the swan’s wings. (Look closer to Deneb than Albireo for them – swans have long necks!) The brighter star in the middle of the wing span is Sadr, marking the swan’s belly. If you are in a dark location, you should also be able to see that the Milky Way runs right through Cygnus, as if she is about to land for a swim on that celestial river! Use your binoculars to explore the swan from head to tail. You’re bound to find little clumps of stars and glowing gas!

The most southerly of the triangle’s corners is marked by Altair – the head of the great eagle Aquila. In fact, its name translates from “the flying eagle”. At only 16.8 light-years distance, Altair is one of the nearest bright stars – so close that its surface has been imaged! The star also seems to be spinning 100 times faster than our sun, probably generating an equatorial bulge. Like Cygnus, the Aquila the eagle is oriented with its wingtips up-down. The tail bends to the lower right. Two little stars named Terazed (above, or north) and Alshain (below, or south) sit on either side of Altair, like a balance. As a matter of fact, those two little stars’ names derive from an old-fashioned scale balance.

Grab your binoculars and look about midway between Vega and Altair for a little grouping of stars called The Coathangar. It’s composed of a rod made by a line of six stars spanning a thumb’s width in length, plus a hook made up of four stars. (Hint: For North American observers, it’s oriented with the hook downwards to the right.) Its fancier names include Brocchi’s Cluster, Al Sufi’s Cluster, and Collinder 399. A Closer look will show that most of the stars are hot, white A- and B-class stars. The other three are cooler, reddish K- and M-class stars.

Finally, have a look for two little constellations in the area. Sagitta (the Arrow) comprises five faint stars, aligned left-right, located midway between Altair and Albireo. The three stars on its right (western) end form the feathers. Just below the middle of the arrow’s span is a fairly bright globular star cluster named Messier 71 or the Angelfish Cluster. Under a dark sky, binoculars should show it as a small, faint, fuzzy star. In a backyard telescope it will resemble a mound of sugar sprinkled on black velvet.

Below Sagitta, and about 1.3 fist diameters to the left (or 13° to the celestial northeast) of Altair is cute little Delphinus (the Dolphin). Four stars form a diamond-shaped body and another star to the lower right of that makes the tail! The proper names for Delphinus’ two brightest stars are Sualocin and Rotanev, which are the Latinized form of the English-translated name of Italian astronomer Niccolò Cacciatore, i.e., Nicolaus Venator . Cacciatore wrote them in a star catalog in 1814, as a joke, and they snuck through and remained in use!

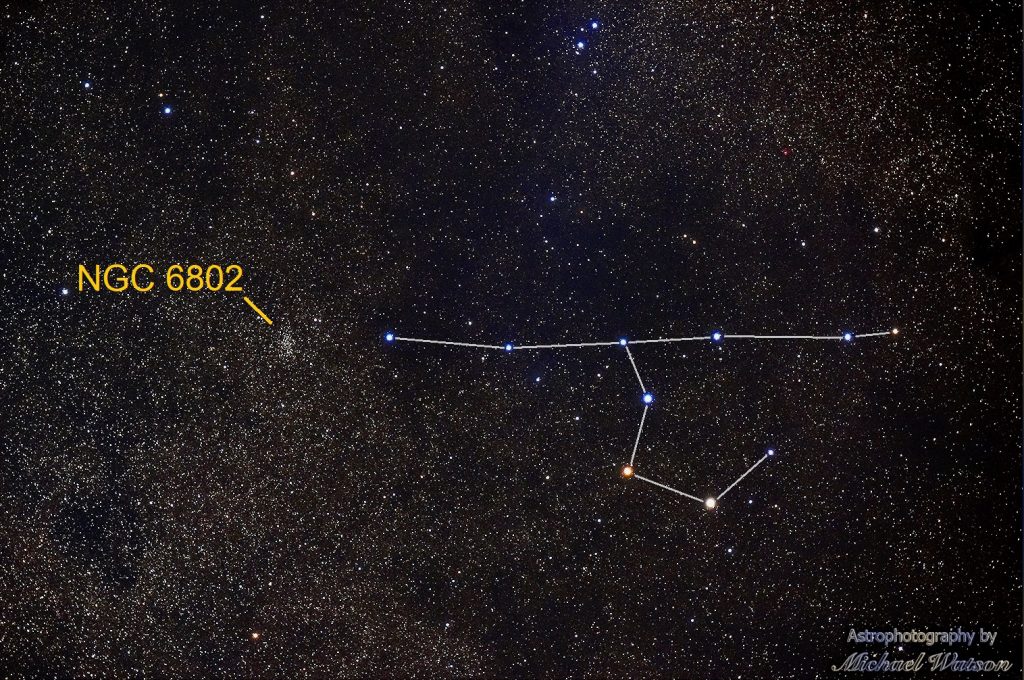

There’s one more small constellation inside the summer triangle, but its dim stars make it difficult to see from the city. It’s called Vulpecula (the Fox). It is made up of only two magnitude 4.5 stars, and is located a palm’s width above (north of) Sagitta, near Albireo. One of Velpecula’s claims to fame, however, is the spectacular planetary nebula known as the Dumbbell Nebula, also known as Messier 27 and NGC 6853. From a dark location aim your telescope just two finger widths above (or 3° to the celestial NNW) of Sagitta’s arrow tip and look for a small, faintly glowing cloud of gas that resembles an apple core.

Two birds, a dolphin, and a fox! Keep a look out for the lizard Lacerta just to the east of these, and the little foal Equuleus sitting below Delphinus! Enjoy your tour of the triangle and visit to this celestial zoo!

Public Astro-Themed Events

Every Monday evening, York University’s Allan I. Carswell Observatory runs an online star party – broadcasting views from four telescopes/cameras, answering viewer questions, and taking requests! Details are here. Their in-person Wednesday night viewing has been converted to online via the observatory YouTube channel.

Don’t forget to take advantage of the astronomy-themed YouTube videos posted by RASC Toronto Centre and RASC Canada.

On Wednesday, July 28 at 5 pm EDT, University of Toronto’s Astronomy and Space Exploration Society (ASX) will present a free online Star Talk by Dr. Cherry Ng entitled Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence using the MeerKAT and the Very Large Array Telescope. The Zoom link and additional details are here.

On Wednesday, July 28 at 7 pm EDT, SkyNews Magazine will continue their weekly online sessions Games in Space – Out of Space featuring editor Allendria Brunjes, Jenna Hinds and guests. Details are here and the registration link is here! Sessions are also live-streamed to YouTube here and can be watched at any time.

My free, family-friendly Insider’s Guide to the Galaxy webcasts with Jenna Hinds of RASC National will return on Tuesday, August 17 with a Gas Giant Planets Special! You can find more details, and the schedule of future sessions, here.

Keep looking up, and enjoy the sky when you do. I love questions and requests. Send me some!