New Moon Brings an Annular Solar Eclipse, Brightest Planets Bracket the Pre-dawn Sky, and Pegasus Points to the Celestial Centre!

This annular solar eclipse occured on June 6, 2021. Proper solar filters or image projection is required to view every part of an annular eclipse.

It’s Solar Eclipse Time, Stargazers!

Here are your Astronomy Skylights for the week of October 8th, 2023 by Chris Vaughan. Feel free to pass this along to your friends and send me your comments, questions, and suggested topics. You can also follow me on Twitter as @astrogeoguy! Unless otherwise noted, all times are expressed in Eastern Time. To subscribe to these emails please click this MailChimp link.

If you’d like me to bring my Digital Starlab portable inflatable planetarium to your school or other daytime or evening event, or deliver a session online, contact me through AstroGeo.ca, and we’ll tour the Universe, or the Earth’s interior, together! I’m proud of my book with John A. Read entitled 110 Things to See With a Telescope. It’s a guide to viewing the deep sky objects in the Messier List – for both beginners and seasoned astronomers. DM me to order a signed copy!

When the apogee moon passes the sun on Saturday, it will produce an annular “ring of fire” solar eclipse visible across the Western Hemisphere. So I share some valuable information about the event. Meanwhile the waning moon will be absent from the night sky, where you’ll be able to enjoy planets, the stars of Pegasus, and the centre of the celestial coordinate system. Morning zodiacal light appears and Algol “blinks” at a convenient time to note it. Read on for your Skylights!

The Moon

This is the week of the lunar month when the orbit of our natural satellite will be carrying it toward the sun. The moon will only be visible as a waning crescent shining in the hours before sunrise – leaving evening skies worldwide extra dark for deep sky exploring.

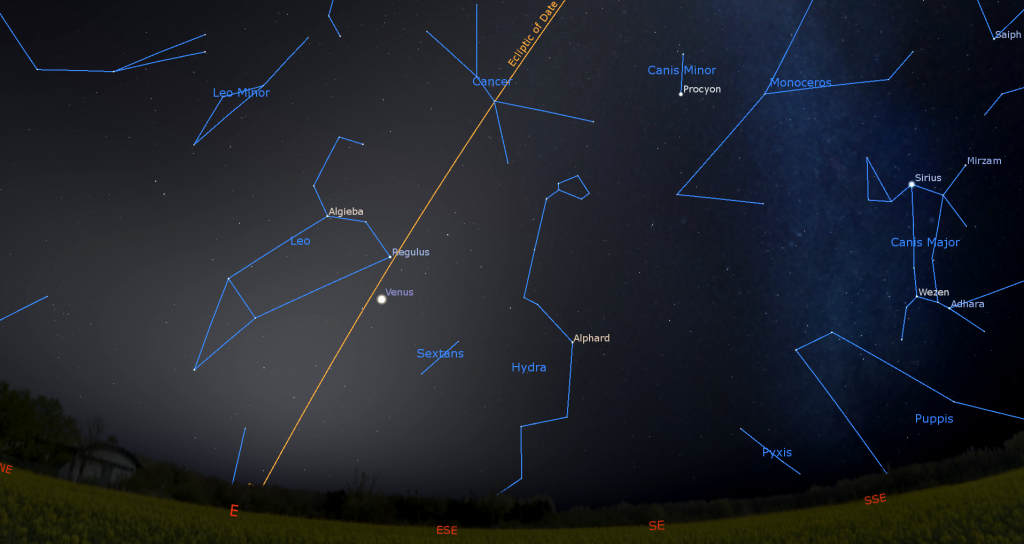

The moon’s closer and closer shift toward the sun each morning will reduce its illuminated phase and shorten its window of visibility. On Monday morning, the 24%-illuminated moon will rise around 2 am local time and shine above the stars forming the face of Leo (the Lion). Brilliant Venus, which has been dominating the eastern morning sky for quite some time, will be a beacon below the moon.

Check the forecast and then set the alarm. On Tuesday morning Venus will travel closely past Leo’s brightest star, Regulus. A pretty sight will greet early risers when the crescent of the old moon will be shining close to the duo for a few hours between 4 am and sunrise. Regulus will sparkle between the moon and the planet. All three objects will look terrific in binoculars and will make a nice photo when composed with some interesting foreground scenery.

The moon will still be crossing through Leo on Wednesday morning. On Thursday it will sneak into Virgo (the Maiden), in stealth mode as a mere 5%-lit crescent that rises around 5 am local time. You can try to spot the moon’s even slimmer crescent sitting low in the east before sunrise on Friday. Normally that would be our last chance to see the moon until it appears in the western sky after sunset a day or two after new moon – but not this time!

The moon will officially reach its new moon phase on Saturday, October 14 at 1:55 pm EDT or 10:55 am PDT and 17:55 Greenwich Mean Time. While new the moon is passing through space between Earth and the sun, so none of the sun’s light can reach the side of the moon that faces Earth. Most of the time, the moon’s 5° orbital inclination carries it above or below the sun at new moon, hiding the moon for a day or so. But this month the moon will reach new while the sun is close to the point in space where the orbit of the moon crosses the ecliptic – the path of the sun through the stars due to Earth’s orbital motion. (The two points in space where two orbits intersect are called nodes.) Since the sun and moon both cover about half a degree of the sky, new moons that occur when the sun is near either node generate a solar eclipse! More on this in a moment.

After the new moon and the eclipse, the young crescent moon, still within Virgo, will join the western sky next Sunday evening. But the severely tilted evening ecliptic will keep it too low for easy spotting unless you live near the tropics.

Annular Solar Eclipse

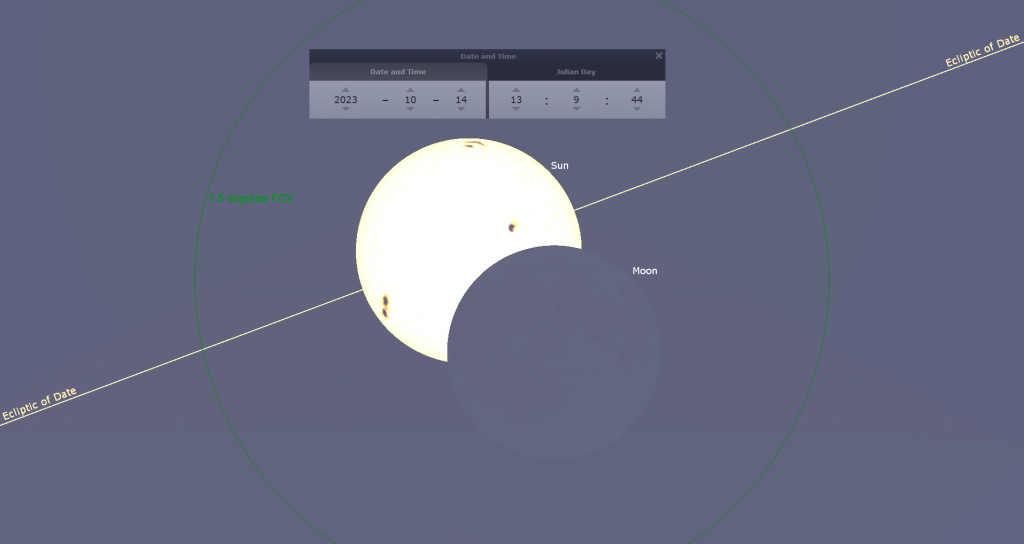

The new moon of Saturday, October 14 will generate an annular solar eclipse. Because the moon will reach its maximum distance from Earth (or apogee) several days beforehand on October 9-10, the moon will be too far from Earth and too small in the sky to fully obscure the sun.

During a regular solar eclipse, observers located in the small region on Earth where the sun is completely obscured by the moon see a total solar eclipse, enjoying the sight of the sun’s corona around the inky black disk of the moon for several minutes. As the moon’s umbral shadow sweeps rapidly across the Earth, it produces a narrow path of totality. (The shadow moves because the moon is orbiting the Earth and because the Earth is rotating at the same time.)

Observers located in a large area adjacent to the path of totality will only see a partial solar eclipse, missing the spectacle that totality brings. That’s why it’s worth making the extra effort to be inside the path of a total solar eclipse. Close doesn’t cut it! The closer you are to the edge of the track, the shorter totality will last, and anyone just a hundred metres outside the track won’t see totality at all.

When the moon is too far from the Earth during a solar eclipse, no part of its umbral shadow makes contact with the Earth’s surface, so no one sees a total eclipse. Instead, the moon’s umbral shadow converges to a point in space and then diverges again into a circular antumbral zone that reaches the Earth’s surface. For Earthlings inside of that zone, the relatively larger disk of the sun shows as a bright ring around the black disk of the smaller moon, meaning that no part of an annular eclipse can be watched in person without special solar filters. The informal name for this annular eclipse is “ring of fire”. The antumbra sweeps across the Earth, too – this time creating a path of annularity. The adjacent surrounding regions see a normal partial solar eclipse.

The October 14, 2023 partial solar eclipse will be visible across all of North, Central, and South America (except for western Alaska, where the moon will already have moved clear of the sun at sunrise), and the parts of South America south of 36° S latitude, where the moon will pass just north of the sun’s disk. Parts of the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans will also see a partially eclipsed sun.

The true annular eclipse, where a ring of exposed sun all around the moon will be seen for a few minutes, will be visible along only a track that slants across the Americas, as shown here. The moon’s antumbra will first contact the Earth in the North Pacific Ocean at 16:12 Greenwich Mean Time or 9:12 am PDT. The corridor of visibility there will be 245 km wide and the ring will appear for 4.3 minutes. The path will sweep southeast, making landfall south of Eugene, Oregon at 16:16 GMT or 9:16 am PDT, with the sun only 17 degrees above the horizon. The path width will have shrunk to 220 km, but the duration will have increased to 4.57 minutes.

The track will cross Nevada, Utah, and corners of the adjacent states. It will pass almost squarely through Albuquerque, New Mexico where the 36° high sun will show a ring for 4.83 minutes starting at 10:34:29 am Mountain Time. After passing through Roswell, NM, too, it will sweep through Odessa, San Antonio, and Corpus Christi, Texas, where the duration will grow to 5 minutes. There, the path will be 190 km wide and the sun will be 49° high when the ring appears starting at 11:55:49 am Central Time.

The antumbra will cross the Gulf of Mexico, then the Mexican Yucatan and northern Guatemala and Belize, then cross northeastern Honduras and Nicaragua between 12:24 and 12:59 pm. The instant of greatest eclipse, when 90.7% of the sun will be obscured and the ring of sunlight will be thickest, will occur just east of the coast of Nicaragua. Annularity there will last for 5.26 minutes with the sun 68° high in the sky. The 190 km wide track will just miss Panama City to its north at 1:13:08 pm.

The ring’s trip across the South American countries of Colombia and Brazil will last from 18:25 GMT to 19:44 GMT, then lift off of the Earth just east of Brazil’s easternmost tip at 19:46 GMT, for a total trip time of just 3.57 hours. Even a fighter jet can’t keep up with an eclipse!

Fred Espenak is the guru of eclipses. His Eclipsewise.com page is the definitive source for solar and lunar eclipses. Fred has listed the annular eclipse circumstances for major Canadian and US locations here. You’ll find his Google Map showing the path here. Mouse over and click a location on the map to see the timings.

Canadians will only see the partial eclipse. The Maritimes will see between 5% and 20% of the sun’s diameter covered by the moon. Montreal will see a maximum of 29% coverage at 1:18 pm EDT, Winnipeg 53% at 11:42 am, Calgary 70% at 10:27 am, and Vancouver 82% at 9:20 am PDT. The farther west you go, the lower the sun will be, but the more of it will be eclipsed.

In the Greater Toronto Area, the moon will start to bite into the sun at 11:55:44 am EDT. Maximum eclipse, with only 39% of the sun covered and the duo positioned a third of the way up the southern sky, will occur at 1:09:44 pm EDT. The moon will end its nibbling of the sun at 2:25:18 pm EDT. Astronomers call that last contact. If you plan to view or photograph the entire 2.5 hour event, it’s a good idea to preview it in Stellarium or another app to see where you will need to set up so that trees or buildings won’t obscure your view.

You do not need to stay indoors during a solar eclipse. As long as you aren’t looking at the sun, you can go about your business as you would on any sunny day.

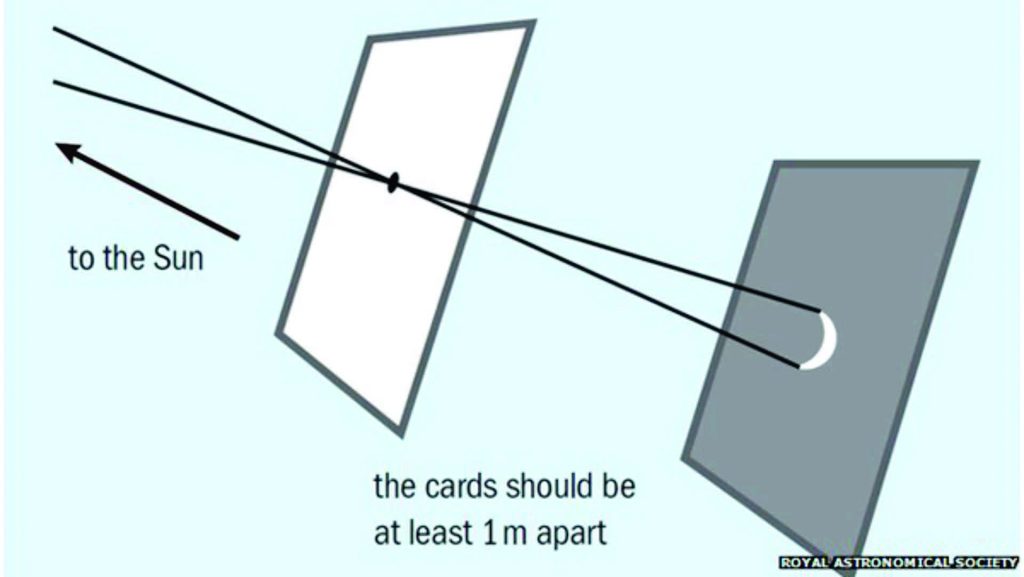

Proper solar filters on your eyes, cameras, binoculars, or telescopes will be required to view any portion of this eclipse in person! Eclipse glasses are available at science shops and in some astronomy magazines. If you don’t have those, you can make a pinhole projector using a cereal or cardboard box and some foil, or simply let the eclipsed sun shine through anything with small round holes in it and look for the little crescents it makes. Instructions for making a projector can be found here and here. Note that a tiny hole will make a small, dim, but crisp sun-shape, and a larger hole will make the same shape, but larger, brighter, and fuzzier.

Thick clouds will ruin the event, but thin clouds can be okay. Weather permitting, many astronomy clubs, museums, science centres, and college/university astronomy departments will host in-person viewing parties with special solar telescopes and eclipse glasses available. If you want to watch the eclipse safely on your computer or mobile device, there are live streams at https://www.timeanddate.com/live/ and others on YouTube. Space.com has more sources listed here.

As usual, this eclipse will be accompanied two weeks from now by a partial lunar eclipse visible only from Africa, Europe and Asia. That’s because the sun will still be near the node when the moon reaches its full phase, causing all three objects to more or less line up again, this time with Earth in the middle.

Morning Zodiacal Light

During autumn at mid-northern latitudes every year, the ecliptic extends nearly vertically upward from the eastern horizon before dawn. That geometry favors the appearance of the faint zodiacal light in the eastern sky for about half an hour before dawn on moonless mornings. Zodiacal light is sunlight scattered by interplanetary particles that are concentrated in the plane of the solar system – the same material that produces meteor showers. It is more readily seen in areas free of urban light pollution.

Between now and the full moon on October 28, try looking for the phenomenon as a broad wedge of faint light extending upwards from the eastern horizon and centered on the ecliptic. It will be strongest in the lower third of the sky, below the bright planet Venus. Try taking a long exposure photograph to capture the zodiacal light, but don’t confuse it with the Milky Way, which will be extending upwards nearby in the southern sky.

The Planets

Although you may be able to spot the reddish dot of Mars lurking just above the western horizon immediately after sunset this week, I’m calling it – Mars viewing is done for this year. The red planet is on the far side of the sun from Earth and looking about as small and as faint as it ever does from here. Earth’s orbital motion is shifting Mars closer to the sun every day, but its own orbital motion is acting counter to that, like a salmon swimming against the current. That will delay Mars’ solar conjunction until November 18. After reappearing in the eastern pre-dawn sky next spring, Mars will spend all of 2024 getting closer to Earth and growing in brightness ahead of its opposition in early January, 2025.

That leaves four planets in the evening sky nowadays – the latest to rise being Uranus, which will join the other three after 8 pm local time.

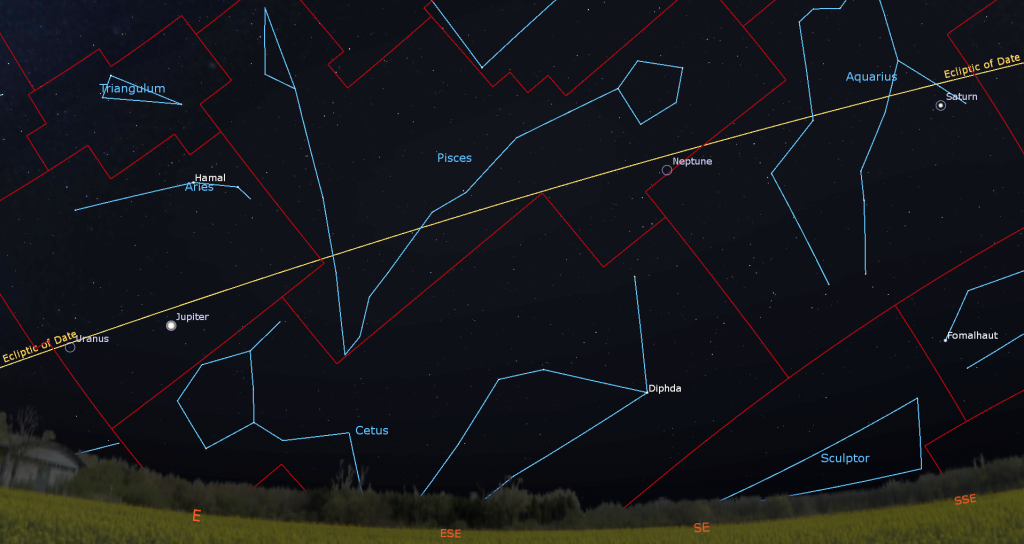

The medium-bright and warm-tinted dot of Saturn will appear in the lower part of the southeastern sky during evening twilight. Then it will be visible all night long while it crosses the sky. You’ll get the clearest views of Saturn in a telescope while it is higher, between 7:30 pm and 1:30 am local time. Once it’s dark, the faint stars of Aquarius (the Water-Bearer) and Capricornus (the Sea-Goat) will be twinkling to the left and right of Saturn, respectively. The bright trio of the Summer Triangle asterism stars will sparkle on high above it, and the Great Square of Pegasus stars will be positioned a few fist diameters to the planet’s upper left. If you have an unobstructed southern view, look for the very bright star Fomalhaut or Alpha Piscis Austrini (the Southern Fish) shining two fist diameters below Saturn.

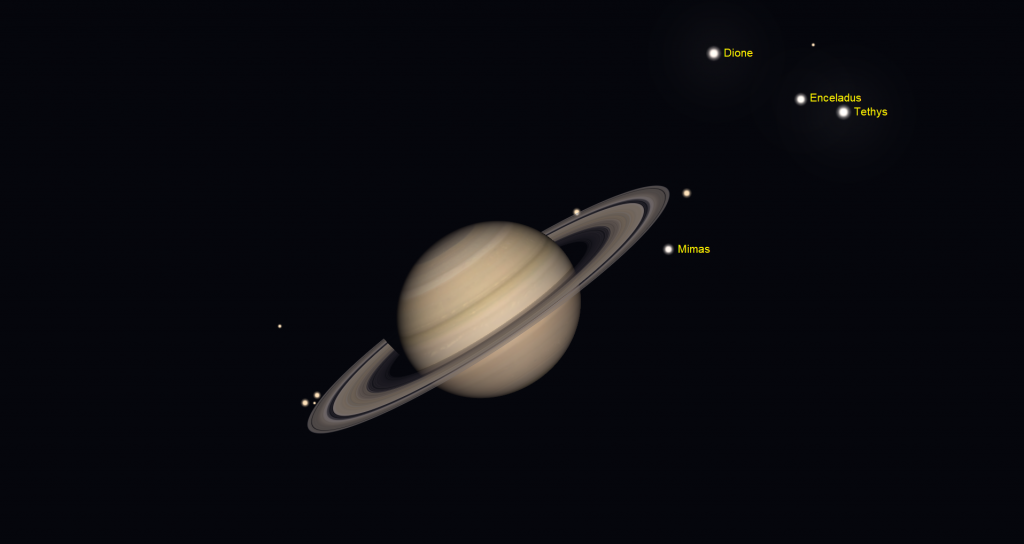

Any size of telescope will show Saturn’s beautiful rings. If your optics are of good quality and the air is steady, try to see the Cassini Division, a narrow gap curving between the outer and inner rings. You can also look for a small wedge of dark shadow cast upon on the rings at the eastern limb of the planet’s globe and faint belts of dark cloud that encircle Saturn. Remember to take long, lingering looks through the eyepiece – so that you can catch moments of perfect atmospheric clarity. Good binoculars can hint at the shape of Saturn’s rings, too.

From here on Earth, Saturn’s axial tilt of 26.7° lets us see the top of its ring plane, and allows its brighter moons to array themselves above, below, and alongside the planet. Saturn’s largest and brightest moon Titan never wanders more than five times the width of Saturn’s rings from the planet. The much fainter moon named Iapetus can stray up to twelve times the ring width during its 80-day orbit of Saturn. The next brightest moons Rhea, Dione, Tethys, Enceladus, and Mimas all stay within one ring-width of Saturn.

During this week, Titan will migrate counter-clockwise around Saturn, moving from close-in on the upper right of the planet (celestial west-northwest) tonight to farther away on the lower left of Saturn (celestial east) next Sunday night. (Remember that your telescope will probably flip the view around.) The rest of the moons will be tiny specks. You may be surprised at how many of them you can see through your telescope if you look closely.

This summer, the ice giant planet Neptune, currently about 790 times fainter than Saturn, will be lurking 2.4 fist diameters to Saturn’s lower left, or 24° to its celestial northeast. Only weeks past opposition for 2023, Neptune is still shining with a slightly enhanced magnitude of 7.8 and is visible in backyard telescopes, especially between 8 pm and 3:30 am local time, when the blue planet is highest. Good binoculars can show Neptune, too – if your sky is very dark. Its blue, star-like disk size is currently a tiny 2.36 arc-seconds across.

Extremely bright Jupiter will be rising in the east around 7:45 pm local time this week. Its best telescope viewing time will commence around 9:30 pm. The two brightest stars of Aries (the Ram), named Hamal and Sheratan, will be shining a generous fist’s diameter above the giant planet this year. The winter constellation of Taurus (the Bull) will follow Jupiter across the sky during the night. Then the bright planet will catch your eye when it gleams in the west on your way to school or work every clear morning. Jupiter shifts east by about one zodiac constellation per year. Next year, it will shine in Taurus.

Binoculars will show you Jupiter’s four Galilean moons in a line beside the planet. Named Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto in order of their orbital distance from Jupiter, those moons complete orbits of the planet every 1.7, 3.6, 7.2, and 16.7 days, respectively. If you see fewer than four moons, then one or more of them is crossing in front of or behind Jupiter, or hiding in Jupiter’s dark shadow – or two of the moons are very close together or occulting one another. You can watch Io pop out from behind Jupiter at 11:43 pm EDT on Friday night. All four moons will gather to Jupiter’s west on Friday and Saturday evening.

Even a small, but decent quality telescope can show you Jupiter’s dark belts and light zones, which are aligned parallel to its equator. With a better grade of optics, Jupiter’s Great Red Spot, a cyclonic storm that has raged for hundreds of years, becomes visible for several hours when it crosses the planet every 2nd or 3rd night. For observers in the Americas, that GRS will cross Jupiter’s disk in mid-evening Eastern Time on Tuesday, Thursday, and next Sunday night. It’ll show in the wee hours of Monday and Saturday morning and before dawn on Monday, Wednesday, and Saturday morning. If you have any coloured filters or nebula filters for your telescope, try enhancing the spot with them.

From time to time, the small, round, black shadows cast by Jupiter’s Galilean moons become visible in amateur telescopes when they cross (or transit) the planet’s disk. On Tuesday morning, October 10, Europa’s small shadow will follow the Great Red Spot across Jupiter from 12:14 to 2:28 am EDT (or 04:14 to 06:28 GMT). On Wednesday morning, October 11, Io’s small shadow will cross Jupiter’s equatorial region with the spot from 5:19 to 7:25 am EDT (or 09:19 to 11:25 GMT). Ganymede’s big shadow will cross Jupiter’s south polar latitudes on Thursday, October 12 from 10:02 to 11:40 pm EDT (or 02:02 to 03:40 GMT on Friday). An hour later Io’s shadow will follow, along Jupiter’s equator, from 11:45 pm to 1:55 am EDT (or 03:45 to 05:55 GMT on Friday). (These times may vary by a few minutes and other time zones of the world will have their own crossings.)

The blue-green ice giant planet Uranus is following Jupiter across the sky this year. Magnitude 5.7 Uranus is visible in both binoculars and small telescopes if you know where to look. It’s located a slim fist’s diameter to Jupiter’s lower left (or 8.6° to the celestial east), just inside Aries’ border with Taurus. The bright little Pleiades star cluster will be located a similar distance to Uranus’ left. This year, a pair of medium-bright stars named Botein and Al Butain IV (or Sigma and Zeta Arietis) will shine two finger widths above Uranus. Since they are easy to see in binoculars, they can act as your guides. Uranus’ small coloured disk is a treat to see in a telescope. The best times for looking start around 10 pm local time.

If you head outside on a clear morning before sunrise this week, the southern sky will be embraced by the brightest planets Venus and Jupiter. They’ll be positioned at about the same height in the sky around 6:45 am, though Jupiter will be descending in the west while Venus climbs in the east.

Venus will occupy the eastern pre-dawn sky from now until January. It will be climbing a little farther from the morning sun with each passing day until October 23. Viewed in a telescope this week, our next door neighbour’s disk will be shrinking in size and waxing toward half-lit. Venus will rise among the stars of Leo (the Lion) at about 3:30 am local time. As I mentioned above, Venus will be shining near Leo’s brightest star Regulus on Monday, with the crescent moon nearby.

Mercury will be hidden near the sun for the rest of October.

Medusa’s Eye Pulses

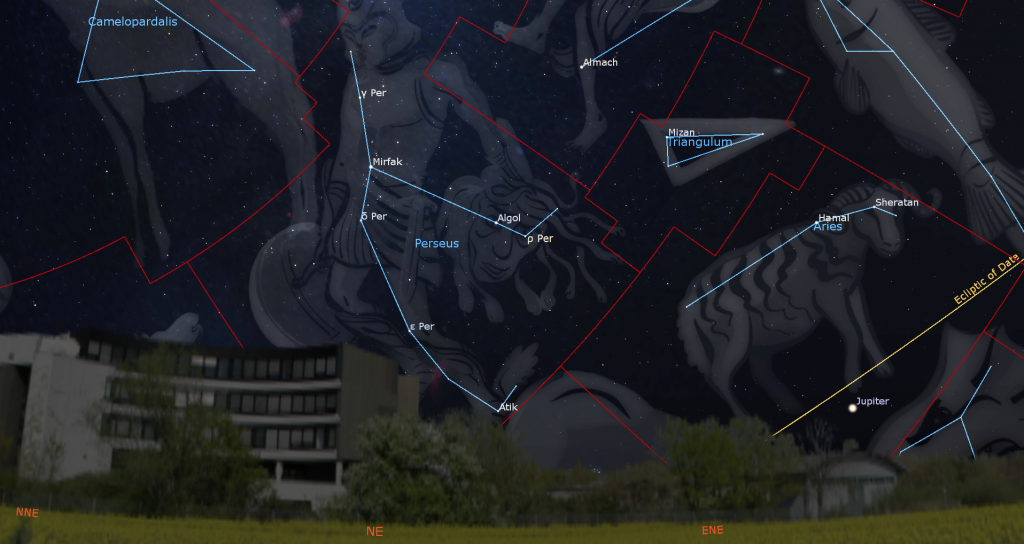

In the constellation of Perseus (the Hero), the star Algol, also designated Beta Persei, marks the glowing eye of Medusa from Greek mythology. The star is among the most accessible variable stars for skywatchers. During a ten-hour period that repeats every 2 days, 20 hours, and 49 minutes, Algol dims by a third and then re-brightens when a companion star with an orbit nearly edge-on to Earth crosses behind the much brighter main star, reducing the total light output we perceive. Algol normally shines at magnitude 2.1, similar to the nearby star Almach in Andromeda (the Princess). But while dimmed to minimum brightness, Algol’s magnitude 3.4 is almost the same as the star named Gorgonea Tertia or Rho Persei (ρ Per), which shines just two finger widths to Algol’s lower right (or 2.25 degrees to the celestial south).

On Thursday evening, October 12 at 8:24 pm EDT or 00:24 GMT, Algol will shine at its minimum brightness. At that time it will be located in the lower part of the northeastern sky. Five hours later the star will return to full intensity from a perch nearly overhead.

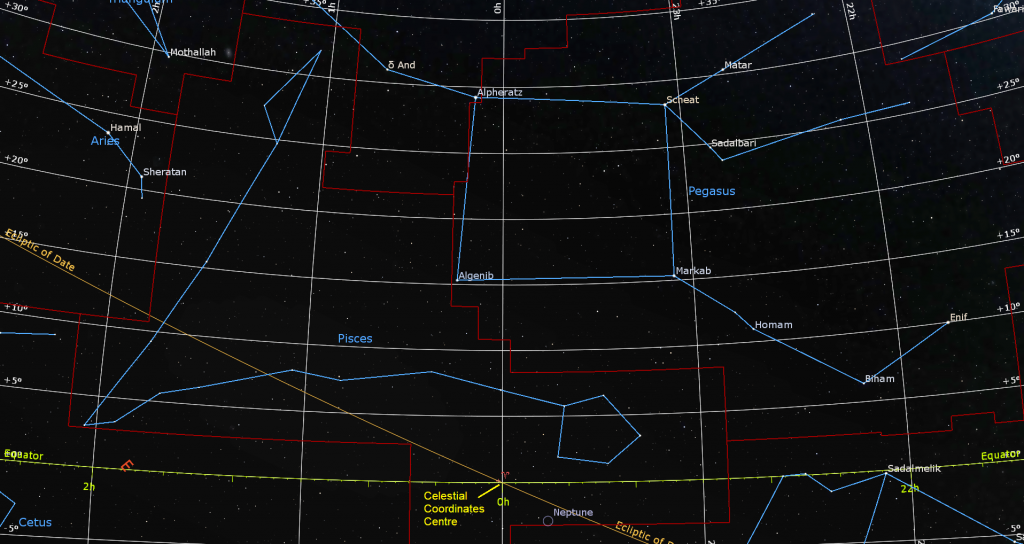

Pegasus and The Celestial Coordinate System

Fall and winter evening skies feature a group of easy-to-see constellations that are characters in a grand story from Greek mythology – the tale of Princess Andromeda and her rescue by the hero Perseus. Last week I toured Aquarius (the Water-Bearer) and its lucky stars here.

The constellation Pegasus (the Winged Horse), which also features in their story, appears in the eastern evening sky in September, becomes well placed for evening astronomy, high in the southern sky from October to December, and then gradually sinks into the western twilight by February. It is one of the largest and oldest of the 88 modern constellations – 7th by area. Since it occupies a place in the sky just north of the celestial equator, it is visible from almost everywhere on Earth. Only Antarctica never sees it rise.

Pegasus contains one of the most obvious asterisms in the sky – a giant square made from four, equally bright stars called the Great Square of Pegasus. Its shape will probably remind you of a baseball diamond when you see it, because it’s usually tilted with one corner downwards. An asterism is a shape or pattern in the sky made up of prominent stars – either stars from a single constellation, or a combination of stars from adjacent constellations. The Big Dipper is an asterism that uses only part of its large constellation Ursa Major.

After it gets dark, face the southeastern sky. The square’s edges are about 16° long (or 1.6 fist widths when held at arm’s length), and about 20° from corner to corner. In mid-October at 9 pm local time, the square’s centre is halfway between the horizon and the zenith. It’s highest in the southern sky at about 11:30 pm local time. It will set in the west during the wee hours. I posted the story and a detailed tour of Pegasus last year here.

The left-hand, eastern side of the Great Square is close to, and nearly parallel to, the prime meridian of the celestial sphere. On Earth, the Prime Meridian stretches from the North Pole southward through Greenwich, UK, and then continues to the South Pole. Earth longitude coordinates are measured east and west from that line using degrees. For the sky’s globe, the prime meridian begins at the north celestial pole near Polaris, and extends southward through the constellations of Cepheus (the King), Pegasus, Aquarius (the Water-Bearer), Piscis Austrinus (the Southern Fish), and the lesser-known (for Northerners) constellations of Grus (the Crane) and Tucana (the Toucan) – ending at the south celestial pole in Octans (the Octant). Unfortunately for astronomers aligning their telescopes in the Southern Hemisphere, there is no bright star marking that pole.

To measure east-west in the sky, astronomers use Right Ascension, abbreviated R.A., instead of longitude. In lieu of circumventing the globe from 180 degrees east to 180 degrees west, with each degree subdivided into minutes and seconds, the Right Ascension units are time, employing the length of Earth’s day, from 0 to 24 hours. The sky coordinate for any object along the prime meridian is both 0 hours 0 minutes 0 seconds, or 00h00m00s, and 24h00m00s. Right Ascension values increase moving east in the sky because an easterly object will rise at a later time than a westerly object.

The square’s eastern corner stars Alpheratz and Algenib are positioned at R.A. 00h09m30s and R.A. 00h14m21s, respectively, about two thumbs’ widths east of the prime meridian. Following that edge north toward Polaris, you’ll pass the bright star Caph in Cassiopeia (the Queen) at R.A. 00h10m19s.

Extending the meridian southward, you’ll cross the Celestial Equator (or declination 0°0m0s) a few finger widths below (or 3.5° to the celestial southeast of) the ring of stars that form the western fish in Pisces. That’s the origin point of the celestial coordinate system. The star that is closest to that spot and bright enough to be visible to your unaided eyes and binoculars is XZ Piscium, a magnitude 5.75, reddish M-class star. It’s only a finger’s width from the 0,0 coordinate. In 2023, Neptune is sitting only a few finger widths to the right of that spot in the sky.

That meridian was selected as prime because the sun passes that point in the sky every year at the Vernal Equinox in March. Over many years, the slow precession, or wobble, of the Earth’s axis of rotation shifts the coordinate system. That’s why star charts are assigned an epoch, such as 2000.0. Apps like Stellarium often report the “of date” or current, celestial coordinates.

The Water Constellations – The Lucky Stars of Aquarius

If you missed last week’s tour of Aquarius (the Water-Bearer) and its lucky stars, I posted it here.

Public Astronomy-Themed Events

Every Monday evening, York University’s Allan I. Carswell Observatory runs an online star party – broadcasting views from four telescopes/cameras, answering viewer questions, and taking requests! Details are here. They host in-person viewing on the first clear Wednesday night each month. Other Wednesdays they stream views online via the observatory YouTube channel. Details are here.

If it’s sunny on Saturday, October 14 from 11:30 am to 2:30 pm, astronomers from the RASC Toronto Centre will be setting up outside on the Green Terrace, Level 3 inside the Ontario Science Centre for the Partial Solar Eclipse. See the eclipsed Sun in detail through special equipment designed to view it safely. Details are here). Parking and admission fees inside the Science Centre will apply.

Space Station Flyovers

The ISS (or International Space Station) will not be visible over the Greater Toronto Area this week.

Keep your eyes on the skies! I love getting questions and requests. Send me some!