Night Falls Earlier, the Crescent Moon in Morning Kisses Venus, Taurus Spits Stars, a Comet, and Andromeda Reclines on High!

Mirach’s Ghost aka NGC404 is the elliptical / lenticular galaxy sitting to the upper left of the bright star Mirach in Andromeda. Other smaller galaxies are scattered around the region. This terrific image by Kent Wood of Utah was the NASA APOD for Oct 27, 2017. Kent’s original image with details of his equipment is at https://www.astrobin.com/315377/?nc=all

Hello, early-November Stargazers!

Here are your Astronomy Skylights for the week of November 5th, 2023 by Chris Vaughan. Feel free to pass this along to your friends and send me your comments, questions, and suggested topics. You can also follow me on Twitter as @astrogeoguy! Unless otherwise noted, all times are expressed in Eastern Time. To subscribe to these emails please click this MailChimp link.

If you’d like me to bring my Digital Starlab portable inflatable planetarium to your school or other daytime or evening event, or deliver a session online, contact me through AstroGeo.ca, and we’ll tour the Universe, or the Earth’s interior, together! My book with John A. Read entitled 110 Things to See With a Telescope is a guide to viewing the deep sky objects in the Messier List – for both beginners and seasoned astronomers. DM me to order a signed copy!

I expand upon Daylight Saving time. The moon passes very close to brilliant Venus before dawn. Meanwhile the moonless evenings are ideal for Taurids meteors, a binoculars comet, four planets, and the sights of Andromeda. Read on for your Skylights!

Falling Back

Did you remember to set your clocks back by an hour? For jurisdictions that employ Daylight Saving Time (or DST, for short), clocks should have been set back by one hour at 2 am local time on Sunday morning, November 5 – or before you went to sleep on Saturday night. In North America the “Fall Back” will remain in effect until Daylight Saving Time reverts to Standard Time when we “Spring Forward” on Sunday, March 10, 2024. The changes occur on the second Sunday morning in March and the first Sunday in November. In the Southern Hemisphere, where the seasons are swapped, the clocks advance in September or October and revert in March or April.

With the end of Daylight Saving Time we’re back to our regularly scheduled program of sunrises and sunsets. Your time zone abbreviation has changed, too. For example, 8 pm Eastern Daylight Time (EDT) is now 7 pm Eastern Standard Time (EST). For those who deal with the timing of astronomical events, the difference between your local time and the international standard Greenwich Mean Time (or GMT), and Coordinated Universal Time (UTC or UT) that astronomers use, is increased by one hour when Daylight Saving Time ends.

For those of us in Toronto, the sun is now rising at about 7 am EST and setting at 5 pm EST. The amount of daylight is decreasing by a whopping 2.5 minutes every day – or 18 minutes every week! The end of astronomical twilight, when the sun is far enough below the horizon for the sky to reach maximum darkness, occurs at about 6:39 pm. As a stargazer, I do appreciate being able to see the stars earlier – but I’m not a fan of the colder temperatures and the cloudier skies of November.

By the way, if you plan to use your telescope on chilly nights, place it in a secure spot outside, with the lens cap on, at least an hour before you head out. That will give the air inside it a chance to equalize with the outside temperature – yielding sharper views. Before you bring the telescope back in, put the lens caps back on to keep the optics from frosting up – or zip the entire telescope into its case if you have one (or snug a garbage bag around it) while it warms to room temperature.

For most of human history, people woke with the sun and went to bed at dusk. At equatorial latitudes, where most people lived, hunted, and farmed, the number of hours of daylight through the year didn’t vary too much – so that approach worked well. But, as communities spread around the globe and began to use standardize working hours – especially at latitudes farther from the equator where the days lengthened and shortened dramatically throughout the year – people were forced to use artificial light indoors when the sun wasn’t shining into windows.

Scientist/naturalist Benjamin Franklin, in a satire he published while living in Paris in 1784, proposed that Parisians get out of bed earlier to take advantage of the early sunrises in summer – and thereby save money on candles and oil in evening. For the same reason, during the 19th Century it became common for schools and businesses to adjust their operating hours with the seasons – but that practice wasn’t standardized.

New Zealand entomologist George Hudson first proposed what became Daylight Saving Time in 1895 – but he wanted the clocks to shift by 2 hours! The idea then spread to England where prominent English builder and outdoorsman William Willett, who was also an avid golfer, noted that more work (and golf) could be fit into the day if the clocks were advanced during the warm months. While the British parliament toyed with the proposal for years, it was Canada that led the way on Daylight Saving Time!

The first city in the world to enact DST, on July 1, 1908, was Port Arthur, Ontario, Canada – followed soon after by Orillia, Ontario. The German Empire and Austria-Hungary adopted DST on April 30, 1916 as a way to conserve coal during World War I. Britain and most of its allies, plus many European neutrals soon followed. The USA adopted DST in 1918. Except for Canada, the UK, France, Ireland, and the United States, DST was abandoned after the war; but it was re-instated during World War II and then widely adopted as a result of the energy crisis of the 1970’s.

The Yukon, most of Saskatchewan, and parts of British Columbia don’t change their clocks, nor do India, China, Russia and swaths of Africa and Australia. The inconvenience of twice-yearly clock changes has led to calls to abandon the practice. Some jurisdictions, including Ontario, Canada and the United States, are proposing to remain on DST year-round. I’d prefer to remain on Standard Time and adjust the school bell times. For stargazers, advancing clocks by one hour, plus the fact that sunset occurs 1 minute later with each passing day near the March equinox, means that spring and summer star parties and dark-sky observing cannot begin until much later in the evening – usually long after the bedtime of junior astronomers! Staying on DST will also mean that existing sundials will be permanently wrong because solar noon will occur at 1 pm, and not at 12 pm.

Meteor Shower Update

The Southern Taurids meteor shower, which runs worldwide from September 28 to December 2 annually, will reach its maximum rate of about 5 meteors per hour tonight (Sunday evening, November 5). Some meteors will appear as the sky darkens on Sunday, but the best viewing time in the Americas will be around midnight, before the bright, waning crescent moon starts to climb the eastern sky. Taurids meteors can appear anywhere in the sky, but they will be streaking away from a point (the radiant of the shower) in western Taurus near Jupiter. The long-lasting, weak shower is the first of two consecutive showers derived from debris dropped by the passage of periodic Comet 2P/Encke. The larger-than-average grain sizes of the comet’s debris often produce colorful fireballs. I saw a very bright one speeding through Pegasus last night!

The Northern Taurids meteor shower, which runs worldwide from October 20 to December 10 annually, will reach its own maximum overnight on Saturday, November 11 in the Americas. The best viewing time for North American skywatchers will be the hours around midnight when the shower’s radiant near the Pleiades star cluster in Taurus will be well above the horizon in a dark, moonless sky. Some Taurids should also be visible on Sunday night. Its meteors will also be travelling away from Jupiter.

To see the most meteors during any shower, find a safe, wide-open, dark location, preferably away from the city lights, and just look up with your unaided eyes for a good long while. Binoculars and telescopes are not useful for meteors because their fields of view are too narrow. Try not to look at your phone’s bright screen because it’ll ruin your night vision. And keep your eyes heavenward, even while you are chatting with companions. I posted an Insider’s Guide to the Galaxy stream all about meteors and meteorites on YouTube here.

The Moon

For everyone on Earth, the moon will be out of the evening sky this week – allowing us to enjoy meteors, sparkling star clusters, and a big galaxy. Our planet’s partner will be approaching the morning sun while it completes the final week of its monthly orbit around us. It reached its third quarter phase this morning (Sunday, November 5) at 3:37 am EST, 12:37 am PST, or 08:37 Greenwich Mean Time. At third (or last) quarter, the moon always looks half-illuminated on the western, sunward side.

At mid-northern latitudes, the waning crescent moon will rise among the stars of Leo (the Lion) around midnight local time on Sunday night. If that’s too late for you, watch for the moon shining high in the southeast before dawn and then keep an eye out for its ghostly form in the western sky as it sinks to set after lunchtime.

The moon will slide about 11° closer to the sun with each passing day this week, causing the moon’s illuminated phase to shrink and its setting time to be delayed. The moon will also be approaching the brilliant “morning star” Venus until Thursday morning.

The moon will spend Tuesday and Wednesday crossing Leo’s stars and closing its gap from Venus. Check the morning weather forecast and then set the alarm for Thursday morning, November 9 to see one of the most spectacular conjunctions of the year. In the eastern sky between 3 am and sunrise, the horns of the pretty crescent moon will shine in Virgo (the Maiden) and less than a lunar diameter to the left (or celestial northeast) of the brilliant planet Venus! The pair will be cozy enough to share the view in a backyard telescope, but binoculars or your unaided eyes will more than suffice. Their meet-up will make a lovely photo when composed with some interesting landscape. This is a world-wide event. Observers in most of Greenland, Iceland, Svalbard, western Russia, Europe (except the Iberian Peninsula), parts of northern Africa, and most of the Middle East can also observe the moon passing in front of, or occulting, Venus in a twilit or daytime sky! (Please take care not to aim optical aids anywhere near the sun.)

On Friday and Saturday morning the moon’s very slim crescent will still be crossing Virgo’s stars. Our last chance to see the old moon will come next Sunday morning, but its razor-thin crescent will be a challenge.

The Planets

The bright gas giant planets are still dominating the evening sky worldwide – but they are not alone. Mercury is lurking above the southwestern horizon for a short time after sunset this week, but it’s too low to be seen from mid-northern locales. If you live in the southern USA, or in the tropics, or in the Southern Hemisphere, you can seek out Mercury’s bright, magnitude -0.6 dot above the sunset point on the horizon after the sun has completely set. Don’t search with binoculars or a telescope until then, however. Our line of sight to Mars is creeping close to the evening sun now, too. The nearby sun will interferes with radio signals to our robotic Mars explorers.

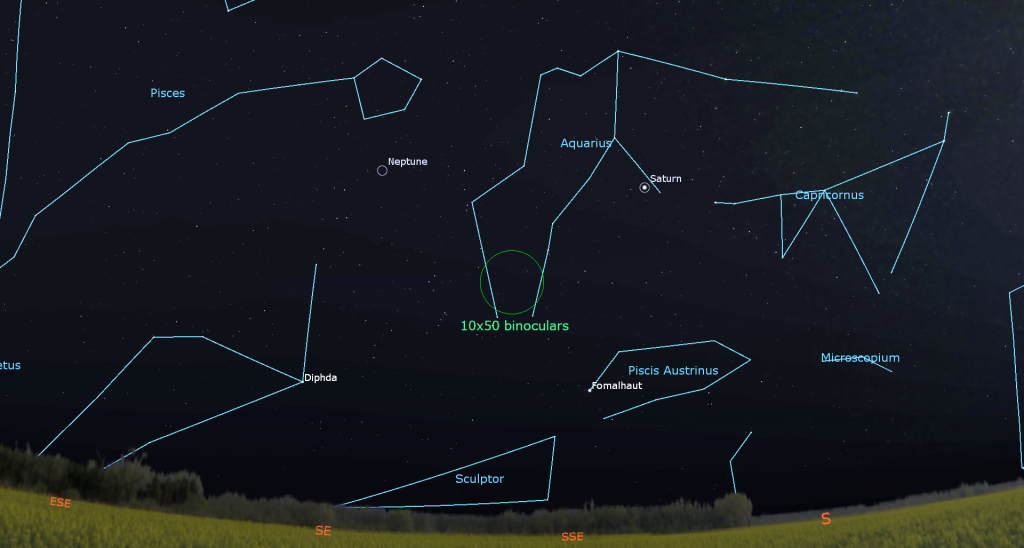

The yellowish dot of Saturn will pop into view in the lower part of the southeastern sky at dusk. Around 7:15 pm local time it will culminate in the south, and then sink westward to set around midnight. Saturn is shining within the borders of Aquarius, but most of the Water-Bearer’s stars are positioned to Saturn’s left (or celestial east). Capricornus (the Sea-Goat) swims to Saturn’s right (or west). Paused for last night’s end to its annual retrograde loop, Saturn will now accelerate into its regular eastward prograde motion across the background stars. I posted a diagram of Saturn’s looping motion here.

The earlier sunsets are granting us northerners more weeks to enjoy Saturn. Any size, style, or brand of telescope will show Saturn’s beautiful rings. If your optics are of good quality and the air isn’t too turbulent, try to see the Cassini Division, a narrow gap that separates the large outer A Ring from the large inner B Ring. I wrote more about the rings here. Good binoculars can hint at the shape of Saturn’s rings, too.

From here on Earth, Saturn’s axial tilt of 26.7° lets us see the top of its ring plane, and allows its brighter moons to array themselves above, below, and alongside the planet. Saturn’s largest and brightest moon Titan never wanders more than five times the width of Saturn’s rings from the planet. The much fainter moon named Iapetus can stray up to twelve times the ring width during its 80-day orbit of Saturn. The next brightest moons Rhea, Dione, Tethys, Enceladus, and Mimas all stay within one ring-width of Saturn.

During this week, Titan will migrate counter-clockwise around Saturn, moving from the right of Saturn (celestial west) tonight to the left of the planet (celestial east) next Sunday night. (Remember that your telescope will probably flip the view around.) The rest of the moons will be tiny specks. You may be surprised at how many of them you can see through your telescope if you look closely.

Speaking of not being alone, the ice giant planet Neptune, currently about 690 times fainter than Saturn, is following the ringed planet across the sky each night. Since Neptune moves so slowly and Saturn has been standing still recently, this week Neptune will still be located 2.5 fist diameters to Saturn’s left, or 25° to its celestial northeast. The diurnal rotation of the sky – the way things tilt as they cross from east to west – will cause Neptune to be lifted increasingly higher than Saturn after 6:30 pm local time. Magnitude 7.8 Neptune is visible in backyard telescopes, especially between dusk and 1 am local time, when the blue planet is highest. Good binoculars can show Neptune, too – if your sky is very dark.

Last Thursday Jupiter reached opposition and peak visibility for this year – but it will still be a spectacular sight for weeks to come. The giant planet will rise in the east around sunset and cross the sky all night long before it sets in the west at sunrise. Jupiter will gleam at magnitude -2.91. Its best telescope-viewing time, when it is higher and therefore less blurred by Earth’s atmosphere, will run from 7 pm to 5 am each night. It’ll catch your eye above the western horizon around sunrise each morning.

The two brightest stars of Aries (the Ram), named Hamal and Sheratan, have been shining a generous fist’s diameter above the giant planet this year. If you are outside on a clear evening this week, and your light pollution isn’t too bad, Aries’ stars will be far outshone by the bright little clump of the Pleiades cluster positioned to Jupiter’s lower left and a bright cloud of stars surrounding Mirfak, the brightest star in Perseus (the Hero). That large, stretched-out patch, known as the Alpha Persei Cluster, Alpha Persei Moving Group, Melotte 20, or the Little Cloud of Pirates, will shine about four fist diameters off to Jupiter’s upper right. The bright, hot O-class and B-class stars in each of those clusters will absolutely dazzle you in binoculars. (Next year, Jupiter’s 12-year orbit will place it into Taurus (the Bull).)

Binoculars will show you Jupiter’s four Galilean moons in a line beside the planet. Named Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto in order of their orbital distance from Jupiter, those moons complete orbits of the planet every 1.7, 3.6, 7.2, and 16.7 days, respectively. If you see fewer than four moons, then one or more of them is crossing in front of or behind Jupiter, or hiding in Jupiter’s dark shadow – or two of the moons are very close together or occulting one another. All four moons will huddle to Jupiter’s left (celestial east) on Thursday evening in the Americas.

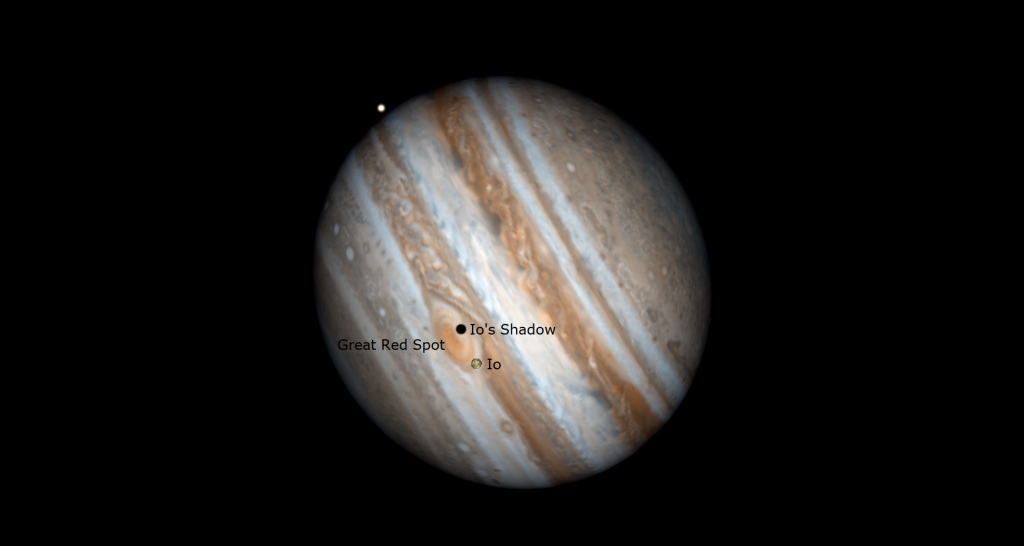

A small, but decent quality telescope can show you Jupiter’s dark belts and light zones, which are aligned parallel to its equator. With a better grade of optics, Jupiter’s Great Red Spot, a cyclonic storm that has raged for hundreds of years, becomes visible for several hours when it crosses the planet every 2nd or 3rd night. For observers in the Americas, the GRS will cross Jupiter’s disk in mid-evening Eastern Time tonight (Sunday), Wednesday, Friday, and next Sunday night. It’ll appear before midnight on Tuesday, Thursday, and next Sunday morning, and before dawn on Tuesday and Thursday morning. If you have any coloured filters or nebula filters for your telescope, try enhancing the spot with them.

From time to time, the small, round, black shadows cast by Jupiter’s Galilean moons become visible in amateur telescopes when they cross (or transit) the planet’s disk. On Monday evening, November 6, Io’s shadow will cross Jupiter from 5:27 to 7:35 pm EST (or 22:27 to 00:35 GMT). Europa’s shadow will venture across Jupiter’s southern latitudes, on Friday evening, November 10 from 10:53 pm to 1:10 am EDT (or 03:53 to 06:10 GMT on November 11). Io’s shadow will cross Jupiter’s equatorial region with the Great Red Spot on Sunday morning, November 12 from 12:52 am to 3:02 am EDT (or 05:52 to 08:02 GMT). Each of those moons will pop into view when it moves off Jupiter at the end of its shadow transit. (These times may vary by a few minutes, and other time zones of the world will have their own crossings.)

Uranus is following Jupiter across the overnight sky. This week the blue-green ice giant planet will be positioned a generous fist’s diameter to Jupiter’s lower left (or 11° to the celestial east), just on the Aries side of its border with Taurus. The diurnal rotation of the sky will lift Uranus to the same height as Jupiter at 10:30 pm local time and then higher still, later. The bright little Pleiades star cluster will be located a similar distance to Uranus’ left (or 10° to the celestial northeast).

Magnitude 5.6 Uranus is visible in binoculars and a treat in a quality backyard telescope of any size. The best time for looking at its small disk will be 7:30 pm to 5:30 am local time. This year, a pair of medium-bright stars named Botein and Al Butain IV (or Sigma and Zeta Arietis) are shining two finger widths above Uranus every evening. Since they are easy to see in binoculars, they can act as your guides. Uranus will reach opposition next week.

Brilliant Venus and Jupiter will continue to book-end the pre-dawn sky this week. If you head outside on a clear morning around 5 am local time, the two planets will be positioned at about the same height in the sky, with Venus due east and Jupiter due west. Sirius, the brightest star in the night sky, will shine between them in the southern sky.

This week, the very bright, magnitude -4.4 planet will rise at about 3 am local time and remain in sight until the rising sun hides it. Due to its swing sunward, Venus will shift a little lower each morning. Viewed through a telescope, Venus will show a waxing gibbous disk spanning 21 arc-seconds. As I mentioned above, the crescent moon will pose extremely close to Venus on Thursday morning.

Comet-watch

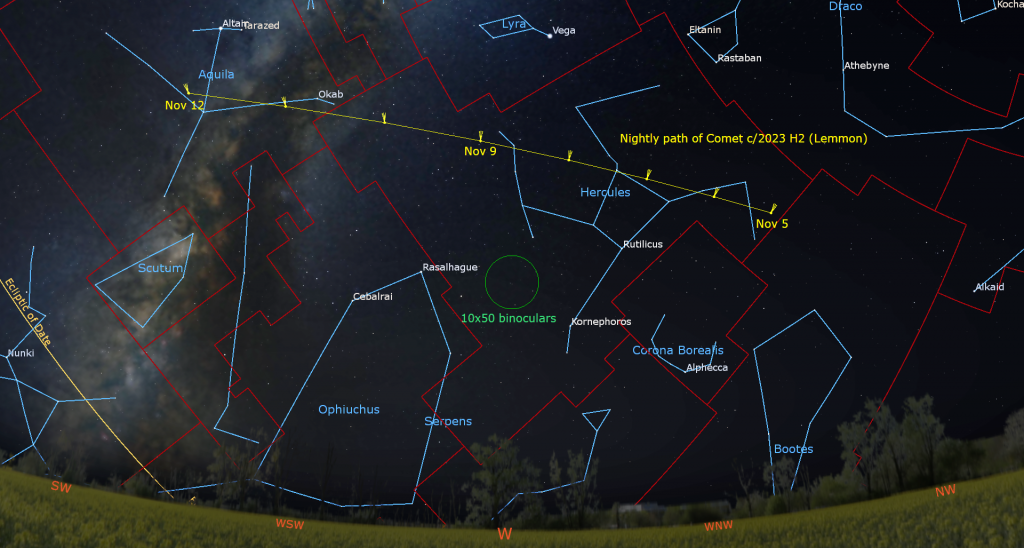

A comet named c/2023 H2 (Lemmon) that is in the western evening sky has brightened enough to be visible in most backyard telescopes and good binoculars under a dark sky on clear, moonless conditions. In the past few days, astronomers have been reporting its brightness to be about magnitude 7.0, although it might brighten at the end of this week when it is closest to Earth.

Comets are speedy! This one will move by about a palm’s width from one night to the next, travelling right-to-left (or southeast) across the constellation of Hercules and into next-door Aquila (the Eagle) on the coming weekend. Since the comet is descending the western sky after dusk, you’ll want to look for it as soon as the sky darkens. If you can identify the keystone shape of Hercules’ body, the comet will be located to its right on Sunday and Monday night, just outside the higher, wider end of the keystone on Tuesday, and then farther and farther to the box’s left from Wednesday to Friday. Next Sunday the comet will pass near the star named Almizan I (or Delta Aquilae) that marks Aquila’s heart. The comet will also move noticeably compared to the surrounding stars. By about the moon’s diameter every 2 hours!

Expect to see a faint grey fuzzy patch. Comets frequently look greenish when viewed in a big telescope or in a long exposure photograph. That colour is produced when diatomic carbon released from the comet’s icy snowball core is ionized by solar radiation.

Admiring Andromeda

During the fall, I like to showcase the constellations involved in the Greek mythological story of Perseus and Andromeda. In early September I toured Andromeda’s father, King Cepheus, here. This week, I’ll tell you about the princess herself. We’ll tour the other constellations in her story in future posts. In the meantime, once upon a time…

Andromeda was the beautiful daughter of Queen Cassiopeia and King Cepheus of Ancient Ethiopia. Through no fault of her own, the princess became the centre of a great tale from Greek mythology. After her mother angered the Nerieds (Sea Nymphs) by boasting of Andromeda’s unrivaled beauty, the god of the sea Poseidon (aka Neptune) sent Cetus, the Sea-monster to ravage Ethiopia’s coast. An oracle told King Cepheus that his only solution was to sacrifice Andromeda to Cetus. So she was chained to rocks by the sea-shore. When Cetus was readying to take Andromeda, the hero Perseus happened to be flying by on his winged sandals. She must have been beautiful indeed, because he instantly fell in love with her, slew the beast, and cut her free from her chains. One drop of the beast’s blood mixed with the sea foam, and Pegasus the flying horse was born. After more adventures, including one where Perseus accidently killed his evil grandfather to fulfill a prophecy, the couple sailed to Argonis, where they raised a family of many children. The mighty Hercules, a summer constellation, is descended from them.

Andromeda is one of the original classical constellations, and is 19th largest by area (out of 88). Also known as the Chained Lady, she is depicted as laying prone with her body and legs extending to the east (left) – the latter formed by two chains of stars that diverge towards her feet. A row of dimmer stars that extends upwards toward the Milky Way represents her chains. Like Pegasus, Andromeda’s location north of the celestial equator means that her stars are visible from everywhere on Earth except Antarctica. A number of ancient cultures saw a woman’s figure in those stars. The ancient Chinese also envisaged legs – but used a different arrangement of stars. You can view a nice portrait of her here. (Parental discretion is advised.) The Navajo saw her stars as a great desert lizard.

A large part of Andromeda’s territory occupies the sky to the left (celestial north of) Pegasus and right (or celestial south) of Cassiopeia. While modern star charts don’t draw lines between any of the medium-bright stars in that part of the sky, classical depictions of the princess assigned those stars to the rocky crag she’s chained to.

Andromeda is visible throughout the fall and winter, but in early November she is found high in the eastern sky, and almost directly overhead during late evening. She is connected to Pegasus on her western (right) side. Her brightest star, named Alpheratz “the Horse’s Shoulder”, marks her head, and also serves as “third base” of Pegasus’ baseball diamond-shaped Great Square. Pisces (the Fishes) swim below her, while Triangulum (the Triangle) is just to the lower left (east) alongside her lower leg. The distinctive W-shaped of Andromeda’s mother Cassiopeia sparkles to her upper left, while her beloved Perseus shines to her lower left (east), under her feet. I’ll post a sky map of the entire set of constellations here.

Let’s tour the best parts of Andromeda, starting at her head, which is marked by bright Alpheratz (or Alpha Andromedae). It’s a hot, blue-white supergiant star located only 97 light-years away from us. The spectrum of this star’s light indicates that it is highly enriched in the metal mercury. To see the rest of the princess, look for two slightly curving horizontal lines of three modest stars each that extend to the lower left (northeast) from Alpheratz. The lower stars are brighter than their higher partners. The lines diverge as you move away from her head, the way her gown would spread out towards her feet.

Tracing the lower line of three stars from Alpheratz, reddish Delta Andromedae (or δ And) sits roughly a palm’s width lower left (east) of Alpheratz, marking the princess’ lower shoulder. The next star, another palm’s width farther, is a bright reddish star called Mirach. The star’s name comes from the Arabic phrase al-Maraqq meaning “the loins” or “the loincloth”. This is a cool, red giant star located 200 light-years from Earth. It produces 1,900 times more light than our sun! Mirach happens to have a 10 million light-years-distant elliptical galaxy tucked in close above it called Mirach’s Ghost (or NGC 404) – but you’ll need a large telescope to see its fuzzy little patch. (Keep Mirach in mind – we’ll return to it later.)

Continuing down to the left by a fist’s diameter, we reach one of Andromeda’s feet – the bright double star named Almach “desert lynx”. Almach’s beautiful golden and sapphire stars easily are seen in a small telescope. The two stars differ in both brightness and colour.

About midway between Mirach and Almach, and a thumb’s width above the line connecting them, sits a medium-bright magnitude 4.1 star named Titawin (or Upsilon Andromedae). The main star is a binary system with a faint, orbiting companion. Four Jupiter-sized exoplanets discovered between 1996 and 2010 orbit that star! Three of the planets have been named after Andalusian scientists: Saffar, Samh, and Majriti. The magnitude 3.55 star that marks Andromeda’s higher foot is an orange-tinted star named Nembus that used to be part of Perseus.

Andromeda’s higher shoulder is marked by a modest star named Pi Andromedae that shines several finger widths above Delta Andromedae.

Now, head down to Mirach and follow Andromeda’s waist / chain upwards. Sitting about four finger widths above Mirach is a dimmer white star designated Mu Andromedae (or μ And). (It’s actually the centre star of Andromeda’s girdle or waist.) A few finger widths above that star sits another even dimmer star named Nu Andromedae (or v And). Look just above that one for a large fuzzy patch. That’s Messier 31 (or M31, for short), better known as the Andromeda Galaxy – one of the sky’s best sights! This massive twin to our Milky Way galaxy spans six full moon diameters across the sky. It has a bright core and dim oval halo that is oriented east-west (left-right). It’s easy to see with binoculars. Using a good sized telescope at low magnification, more treasures are revealed – including two smaller elliptical galaxies sitting just above and below the main galaxy. The smaller of the two, named M32, is positioned nearer to M31’s centre. It is closer to us than the big galaxy. The other, named M110, is farther – in the background.

Under dark skies, you should be able to glimpse the Andromeda Galaxy using unaided eyes only. At about 2.5 million light years away, it’s one of the farthest objects visible to unaided human eyes! We’re going to collide with it in 4 or 5 billion years, but that’s another story!

Aim your binoculars a fist’s diameter above the Andromeda Galaxy, or above and between Alpheratz and the top star of Cassiopeia (named Caph), and look for a scattering of medium-bright stars with a variety of colours. They represent the rocks I mentioned above. In 1787 astronomer Johann Bode used a handful of the stars to create a constellation named Honores Friderici or Frederici Honores, (the Regalia of Frederic) after Frederick the Great, the king of Prussia who had died in the previous year. Lambda, Kappa, and Iota formed a kind of hilt and Psi and Omicron above and below them, respectively, formed the sceptre. A (parental discretion advised) chart of it is here.

Andromeda contains two more interesting deep sky objects. A large, loose open star cluster named NGC 752 is located below and between Almach and Mirach. Look for a tight little triangle of warm-tinted stars in its core and a bright pair of close-together stars at its edge. On the opposite end of the constellation, about 1.5 fist diameters above Alpheratz is the Blue Snowball (or NGC 7662). This magnitude 8.3 planetary nebula, the decaying corpse of a star of similar mass to our own sun, is fairly easy to see in backyard telescopes – but it’s tiny. In your telescope, look for a non-twinkling dot with a faint blue-green colour.

Public Astronomy-Themed Events

Every Monday evening, York University’s Allan I. Carswell Observatory runs an online star party – broadcasting views from four telescopes/cameras, answering viewer questions, and taking requests! Details are here. They host in-person viewing on the first clear Wednesday night each month. Other Wednesdays they stream views online via the observatory YouTube channel. Details are here.

Keep your eyes on the skies! I love getting questions and requests. Send me some!