Peering at Planets from Dusk to Dawn, and Eyeing Aquila on Moonless Nights!

This image of the Wild Duck Cluster, also known as Messier 11 and NGC 6705 in Scutum covers a patch of sky equal to the diameter of the full moon. The magnitude 6.3 open star cluster is visible with unaided eyes and through binoculars and telescopes, despite its 6200 light-year distance. It was taken using the Wide Field Imager (WFI) on the MPG/ESO 2.2-metre telescope at ESO’s La Silla Observatory in Chile.

Hello, Dark-sky Stargazers!

Here are your Astronomy Skylights for the week of August 21st, 2022 by Chris Vaughan. Feel free to pass this along to your friends and send me your comments, questions, and suggested topics. You can also follow me on Twitter as @astrogeoguy! Unless otherwise noted, all times are expressed in Eastern Time. To subscribe to these emails please click this MailChimp link.

If you’d like me to bring my Digital Starlab portable inflatable planetarium to your school or other daytime or evening event, or deliver a session online, contact me through AstroGeo.ca, and we’ll tour the Universe, or the Earth’s interior, together! My terrific new book with John A. Read entitled 110 Things to See With a Telescope is a guide to viewing the deep sky objects in the Messier List – for both beginners and seasoned astronomers. DM me to order a signed copy!

The moon will be gone from the night sky worldwide this week as it travels near the sun, so let’s tour Aquila, the Eagle, which soars beside the Milky Way. Post-opposition Saturn will still look terrific, and asteroid Vesta will reach opposition on Monday evening. Meanwhile, Jupiter and Mars will continue the planet parade overnight, with Venus near winter stars at dawn. Read on for your Skylights!

The Moon

The moon will be missing from evening skies worldwide this week while it swings towards, and then past, the sun. That will make stargazers everywhere happy! If you can leave the light-polluted skies of the city and get to a dark, rural location – even without a telescope – the majestic Milky Way will arch overhead. Take advantage!

For the first few days of this week, if you happen to be up for a bathroom break in the wee hours, or outside during the hours before dawn, you can catch the waning crescent moon visiting the winter constellations. On Monday morning, it’ll be close to the stars forming the feet of Castor in Gemini (the Twins). Use binoculars to scan the sky a few finger widths to the moon’s right (or celestial southwest) to see the grey clump of stars in the Shoe-Buckle Cluster (Messier 35). On Tuesday morning, the aging moon will be shining in the centre of that constellation.

On Wednesday and Thursday, the moon will rise among the faint stars of Cancer (the Crab) at around 4 am local time. On Thursday before 5:30 am, use those binoculars to seek out the swarm of stars in Cancer’s big Beehive Cluster (Messier 44). It’ll be found a few finger widths to the upper right of the moon’s extremely thin, but pretty crescent. That’s close enough for them to share the view in binoculars.

The moon will be very difficult to spot above the east-northeastern horizon in the brightening sky on Friday morning. On Saturday, August 27 at 4:17 am EDT or 1:17 am PDT and 08:17 Greenwich Mean Time, the moon will officially reach its new moon phase. At that time our natural satellite will be located in Leo (the Lion), 4.3 degrees northeast of the sun. While new, the moon is travelling between Earth and the sun. Since sunlight can only illuminate the far side of the moon, and the moon is in the same region of the sky as the sun, it becomes completely hidden from view from anywhere on Earth for about a day.

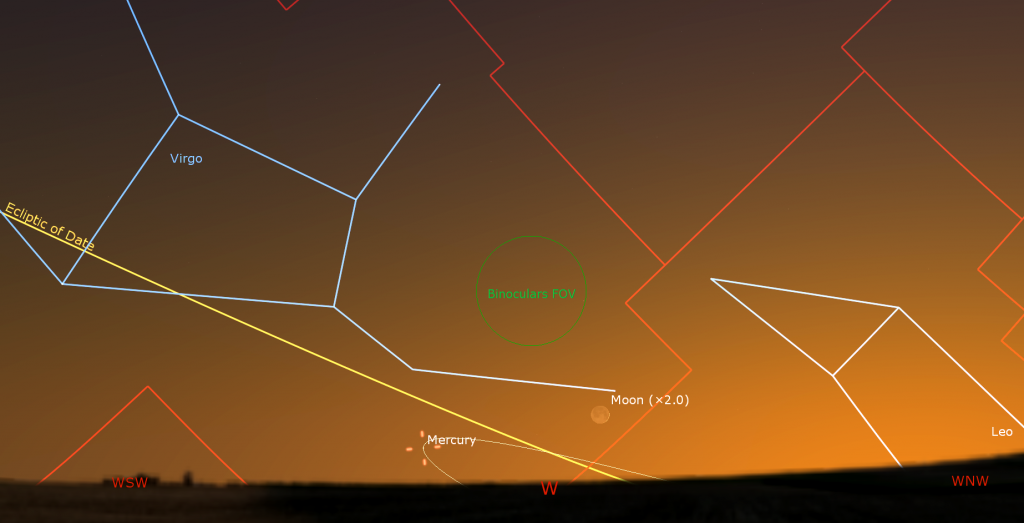

On Saturday, Earth’s celestial night-light will return to shine as a skinny, young crescent in the bright, western sky for a short time after sunset. The moon will be somewhat easier to see above the western horizon after sunset on Sunday. If you live near the tropics, it will be easy, and Mercury will shine to the moon’s left (celestial southeast). The waxing moon won’t really hinder your stargazing until August 31!

The Planets

We’ll still be able to see all the planets between sunset and sunrise this week, but the two innermost planets will be challenging. Mercury will lurk just above the western horizon after sunset all week long, but its position below a very slanted ecliptic will keep the speedy planet too low for easy viewing from mid-northern latitudes. Observers at Caribbean latitudes and south of there will see Mercury easily all month long – its best appearance of the year. After sunset on Saturday, Mercury will be just hours past its widest separation of 27 degrees east of the Sun, normally the finest time to see it. Viewed in a telescope from the tropics that day, the planet will exhibit a waning, half-illuminated phase. The young crescent moon will shine a fist’s diameter to Mercury’s right.

Saturn will already be above the southeastern horizon by sunset. Once the sky is truly darkening, around 9 pm local time, Saturn’s medium-bright, creamy-tinted dot will be clearing trees and rooftops. Saturn will look best in a telescope when it’s high in the southern sky around midnight, but you can certainly start looking as soon as you can focus on it. It will set in the west-southwest before dawn. Last week Saturn passed opposition for 2022, when it was largest and brightest; but it’s still spectacular now, and for the rest of this year. In fact, Saturn’s peak viewing window will shift earlier by half an hour each week.

Even a small telescope will show Saturn’s disk encircled by its rings. Saturn’s rings will become more edge-on to us every year until the spring of 2025. They have already closed enough for Saturn’s southern polar region to extend well beyond them. See if you can see the Cassini Division. It’s a narrow, dark gap that separates Saturn’s main inner ring from its outer one. Over the coming weeks, Saturn’s slide to the west of the anti-solar point will cause Saturn’s globe to cast a widening wedge of dark shadow onto the rings where they emerge from behind the planet.

A small telescope can also show several of Saturn’s moons – especially its largest, brightest moon, Titan! From here on Earth, Saturn’s axial tilt of 26.7° lets us see the top of its ring plane, and allows its brighter moons to array themselves all around the planet. Saturn’s largest and brightest moon Titan never wanders more than five times the width of Saturn’s rings from the planet. The much fainter moon named Iapetus can stray up to twelve times the ring width during its 80-day orbit of Saturn. The next brightest moons Rhea, Dione, Tethys, Enceladus, and Mimas all stay within one ring-width of Saturn. During evening this week, Titan will migrate counter-clockwise around Saturn, moving from the left (celestial northeast) of Saturn tonight (Sunday) to below (celestial south of) the planet next Sunday. (Remember that your telescope might flip that view around.) How many of the moons can you see in your telescope?

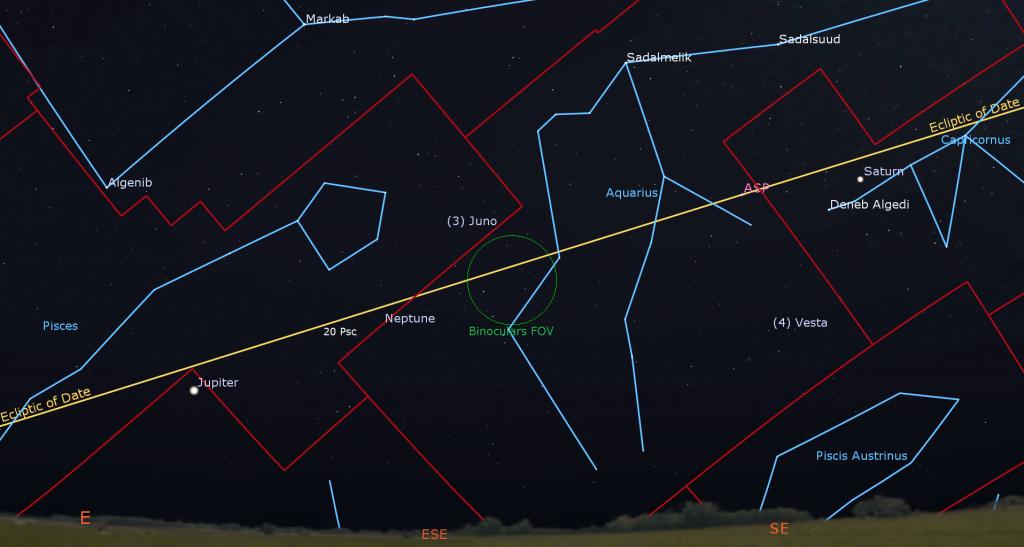

This year Saturn is shining among the faint stars of eastern Capricornus (the Sea-Goat). The two small stars shining a thumb’s width apart to Saturn’s lower left (or celestial southeast) are Deneb Algedi on the left (east) and Nashira on the right (west). They represent the tail of Capricornus (the Sea-Goat). Since Saturn is moving slowly westward in a retrograde loop that will last until late October, you can watch it shift more to the right above those stars every week. (Retrograde loops occur when Earth, on a faster orbit closer to the sun, passes the distant planets and asteroids “on the inside track”, making them appear to move backwards across the stars.)

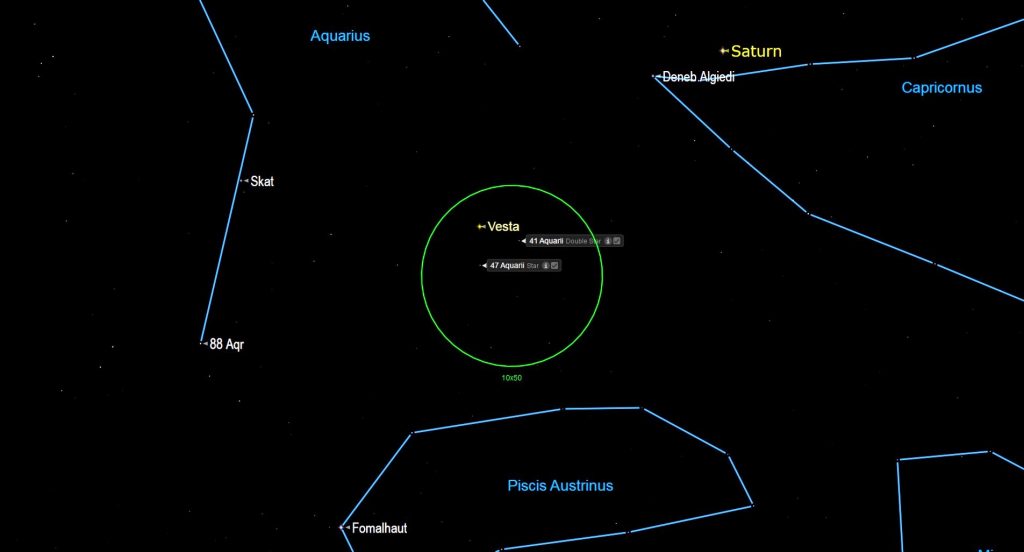

On Monday, the Earth’s orbital motion will carry us between the minor planet designated (4) Vesta and the sun. Because it will be opposite the sun in the sky, Vesta will be visible all night long, and shine at its brightest for the year (magnitude 5.6) – well within reach of binoculars and small telescopes. Look for the asteroid in southwestern Aquarius (the Water-Bearer), approximately midway between Saturn and the bright star Fomalhaut. On the nights surrounding Monday, Vesta will form the upper left (or northern) corner of an isosceles triangle with the medium-bright stars named 41 and 47 Aquarii.

This week, extremely bright, white Jupiter will be shining above the eastern horizon shortly after 10 pm local time, and then spend the night following 17 times fainter Saturn across the sky. Jupiter will climb high enough to look good in any telescope after 11 pm local time – and will look sharpest during the wee hours. Early risers can spot the planet halfway up the southwestern sky before sunrise. Good binoculars will show Jupiter’s disk flanked by its row of four Galilean moons Io, Europa, Ganymede and Callisto, which complete orbits of the planet every 1.7, 3.6, 7.2, and 16.7 days, respectively. If you see fewer than four of them, then one or more is crossing in front of or behind Jupiter – or lurking in Jupiter’s dark shadow – or two moons are occulting one another. Any size of telescope will show Jupiter’s dark bands running parallel its equator.

Because Jupiter rotates once every 10 Earth hours, we can use a good backyard telescope to watch the pale-looking Great Red Spot cross the planet every 2nd or 3rd night. For observers in the Americas, the GRS will cross Jupiter’s disk late on Tuesday, Thursday, and Sunday night, and also during the wee hours of Tuesday, Thursday, and Sunday morning. The small, black shadows of Jupiter’s Galilean moons are visible through a good backyard telescope when they cross the planet’s disk. Io’s tiny shadow will cross Jupiter with the Great Red Spot on Tuesday morning from 1:20 am to 3:30 am EDT. Then Ganymede’s big shadow will repeat the show from 4:05 to nearly 7 am EDT. By that time, the sky will be brightening in the Eastern Time zone.

Magnitude 7.8 Neptune is lurking between Jupiter and Saturn nowadays. It’s theoretically observable in binoculars, but a good telescope makes it far easier. This month, the distant planet’s faint, blue speck will be positioned 1.3 fist diameters to Jupiter’s upper right, and a thumb’s width to the upper right (or 1.7° to the celestial west-southwest) of a small star named 20 Piscium. Neptune has a large moon named Triton that is visible in large aperture telescopes, especially during the next couple of months when we’re closer to the planet.

The medium-bright, reddish dot of Mars will rise above the east-northeastern horizon shortly before midnight local time and will be clearing the eastern rooftops after about 12:45 am local time. Watch for the bright little Pleiades star cluster shining a palm’s width above the planet. Mars will be brightening and growing larger as Earth’s faster orbit draws us closer to it over the coming months. In a telescope, Mars will show a tiny, 85%-illuminated disk.

Magnitude 5.73 Uranus will be located s generous fist’s width to the upper right (or celestial west) of Mars. Since Mars is speeding away eastward, their separation will grow from 12° to 16° over this week. Without Mars to help you, the brightest guidepost to Uranus is the medium-bright star named Botein (or Delta Arietis), which will appear several finger widths to Uranus’ left (or 3° to the celestial northeast). On Wednesday, Uranus’ easterly motion across the stars of southeastern Aries (the Ram) will slow to a stop as it prepares to commence a westward retrograde loop that will last until January, 2023. Uranus will be easiest to see when it’s higher in the sky in the hour before dawn.

Extremely bright Venus will rise in the east at about 5 am local time this week – but it won’t climb very high before sunrise – unless you live in the tropics. The planet is slowly descending toward the sun, so we’ll lose it completely around mid-September. If you are viewing the scene by 5:30 am, enjoy the two bright stars Castor and Pollux shining above the planet, and the tilted form of Orion (the Hunter) off to their right. The pretty crescent moon will join the tableau on Wednesday and Thursday. Take a picture!

Aquila the Eagle

Look halfway up the southern sky on late August evenings, and you’ll easily spot the bright, white star Altair sitting at the bottom corner of the Summer Triangle asterism. Altair is the brightest star in the venerable constellation of Aquila (the Eagle) and marks the great bird’s head. The eagle’s body and tail extend downwards to the right (or celestial southwest), more or less following the Milky Way. The wings extend upwards and downwards.

The great bird’s location close to the Milky Way has populated it with rich star fields. The celestial equator passes through it – allowing it to be seen easily by both Northern and Southern Hemisphere skywatchers. On the right (west) it is bordered by Scutum (the Shield), Serpens Cauda (the Snake’s Tail), and Ophiuchus (the Serpent-Bearer). Sagittarius (the Archer) and Capricornus (the Sea-Goat) are below it (south), and cute little Delphinus (the Dolphin) and Sagitta (the Arrow) above (north). A section of Hercules (the Hero) touches the eagle’s northern wingtip. In area, the bird spans three fist diameters square, or 30° by 30°, but the bright stars only cover about 20°, from head to tail and wing tip to tip.

Aquila so clearly resembles a bird that many cultures saw the same pattern in its stars, including the Babylonians. In Greek mythology, it was the eagle that held Zeus’ thunderbolts. The Romans called it Vultur volans “the flying vulture”. The Hindus associated the stars with the half eagle-half human god Garuda.

Classic Chinese poetry told a well-known story about the Weaver Girl and the Cowherd, one of their four great folktales. In the story, Zhī Nǚ (织女) the weaver girl was in love with Niú Láng (牛郎) the cowherd. To prevent their forbidden love, they were banished to the heavens. Zhi Nu, represented by the nearby bright star Vega, and Niu Lan, represented by Altair, were separated by the Silver River, i.e., the Milky Way. The two small stars which are visible just above and below Altair represent their children. As the story goes, each year on the 7th day of the 7th month in the Chinese lunisolar calendar, a flock of magpies would form a bridge, reuniting the lovers for one night only. In some years, the lunisolar calendar begins at the end of January, putting their 7th month into August. I suspect that those magpies were actually Perseids meteors, which travel parallel to the Milky Way every August.

The name Altair arises from the Arabic expression for “flying eagle”. The star itself is warm-white and of spectral class A7Vn, about ten times larger than our sun. It’s a mere 17 light-years away, making it the twelfth brightest star in the night sky worldwide. Altair’s 10-hour rotation rate is one of the fastest known for stars, spinning so rapidly that the star has an oblate shape (wider at the equator than it is tall). In the sky, Altair is symmetrically flanked by two small stars named Alshain and Tarazed, or β and γ Aquilae, respectively. Because the three stars resemble a weighing balance, their names are derived from the Arabic phrase for one: “shahin-i tarazu”.

The trio spans about three finger widths, or 5° of sky. Higher (more northerly) and brighter Tarazed is interesting. This orange, K3II-class star is 395 light-years-away. It is young, but highly evolved – already burning core helium, and it emits almost 3,000 times the luminosity of our sun. It also emits an abundance of X-rays! Magnitude 3.7 Alshain is located two finger widths below (or 2.7° south-southeast of) Altair. This 44.7 light-years-away, yellowish G8IV-class star has also exhausted its core hydrogen and is evolving into a giant star.

The rest of Aquila’s main stars are fainter, but nonetheless visible to unaided eyes under a dark sky. Almost a fist’s diameter to the lower right (southwest) of Altair is the star Delta Aquilae, or Almizan I, representing the eagle’s body. The wings, each a generous fist’s diameter (11°) in length, extend up and down from that star. The upper wingtip is marked by the white star Deneb al Okab Australis, or Zeta Aquilae, and a slightly dimmer star named Deneb al Okab Borealis. Those names mean the southern and northern “tail of the eagle”. (The reference to the tail arose by using a different interpretation of the star patterns.)

The lower wing is formed by two widely spaced stars. Almizan II is at the elbow, and Almizan III is at the wingtip. (Some apps use the designations Eta Aquilae and Theta Aquilae, respectively.) The eagle’s tail is marked by a pair of small stars separated by a finger’s width. The brighter tail star is named Al Thalimain Prior “the front ostrich”. The Pioneer 11 spacecraft, launched in 1973, is coasting towards this star, with an arrival time in about 4 million years! The “rear ostrich” is the star Iota Aquilae, which sits above and between the tail and the lower wingtip. Those names appear to be left-over from a previous version of the constellation.

Almizan II, the lower elbow star, is a Cepheid variable star that doubles in visible brightness from magnitude 3.5 to 4.4 on a 7.18 day cycle. At maximum, it shines almost as brightly as Lambda Aquilae, the tail of the eagle. At minimum, it’s as faint as Iota Aql, the “rear ostrich”. Try comparing the brightness of those three stars on different nights and see the difference!

Sweep your binoculars though the area around and above Aquila to see an abundance of stars from the nearby galactic plane, and a dark dust lane. About three finger widths to the right (or 4° WSW) of the eagle’s tail, in the next-door constellation Scutum (the Shield), you’ll easily spot another avian object – the Wild Duck Cluster or Messier 11 – a famous bright open cluster.

Within a binoculars’ field of view to the lower right of Okab are two more open star clusters named NGC 6738 and NGC 6709. Another binoculars’ field diameter to their lower right is a bigger, brighter cluster called the Tweedledee Cluster, or Graff’s Cluster.

If you have a large telescope, or if you are observing Aquila under dark, rural skies, aim your telescope a few finger widths along the eagle’s upper wing and look at the round planetary nebula named the Ghost of the Moon, or NGC 6781. It’s not very bright, but it’s huge – more than twice as large as Jupiter!

Let me know if enjoy the Eagle!

Moonlight Sights

The moon-tolerant sights I described last week here will still be around during this moonless week.

Public Astro-Themed Events

Every Monday evening, York University’s Allan I. Carswell Observatory runs an online star party – broadcasting views from four telescopes/cameras, answering viewer questions, and taking requests! Details are here. They host in-person viewing on the first clear Wednesday night each month. Other Wednesdays they stream views online via the observatory YouTube channel. Details are here.

My free, family-friendly Insider’s Guide to the Galaxy webcasts with Samantha Jewett of RASC National returns on Tuesday, September 13 at 3:30 pm EDT, when we’ll do learn about variable stars! Plus, we’ll continue with our Messier Objects observing certificate program. You can find more details and the schedule of future sessions here.

Don’t forget to take advantage of the astronomy-themed YouTube videos posted by RASC Toronto Centre and RASC Canada.

Keep looking up, and enjoy the sky when you do. I love questions and requests. Send me some!