Planets Precede Sunrise, Wishing Stars Outshine the Strawberry Moon and Solstice Signals Summer!

When the moon is full, and within hours on either side of that phase, there are no shadows cast anywhere. All of the variations we see are due to changes in the moon’s geology. This image by Michael nicely shows the numerous rays systems emanating from the younger craters, the various types of dark basalt in the maria, and the triangle of dots (at centre) that are the remnants of former volcanic vents.

Greetings, Summer Stargazers!

Here are your Astronomy Skylights for the week of June 16th, 2024 by Chris Vaughan. Feel free to pass this along to your friends and send me your comments, questions, and suggested topics. You can also follow me on Twitter as @astrogeoguy! Unless otherwise noted, all times are expressed in Eastern Time. To subscribe to these emails please click this MailChimp link.

If you’d like me to bring my Digital Starlab portable inflatable planetarium to your school or other daytime or evening event in Simcoe, Grey, and Bruce Counties, or deliver a virtual session anywhere, contact me through AstroGeo.ca, and we’ll tour the Universe, or the Earth’s interior, together! My book with John A. Read entitled 110 Things to See With a Telescope is a guide to viewing the deep sky objects in the Messier List – for both beginners and seasoned astronomers. DM me to order a signed copy!

Summer will arrive in the Northern Hemisphere this week, and the Full Strawberry moon will hide all but the brightest stars – so I explain the solstice and highlight some lunar features and the first stars to appear each evening. Venus and Mercury are getting ready to appear in the west after sunset. For now, the rest of the planets continue to pose in the eastern pre-dawn sky. Read on for your Skylights!

The June Solstice Starts Northern Summer

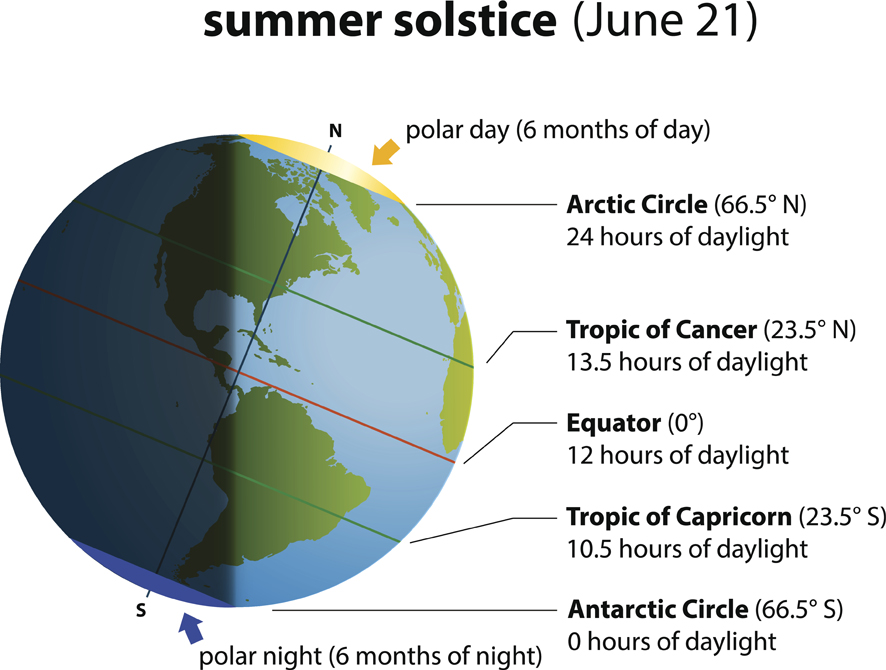

The beginning of summer for Earth’s Northern Hemisphere, known as the June Solstice or Summer Solstice, will occur on Thursday, June 20 at 4:51 pm EDT or 1:51 pm PDT and 20:51 Greenwich Mean Time. At that moment in time, the northern end of Earth’s axis of rotation will be tilted by its maximum amount of 23.44° towards the sun.

On the summer solstice, the sun will climb to its highest mid-day position in the sky for this year. At local noon, your shadow will be shorter than at any other day. The sun will take the longest to cross the daytime sky – maximizing the amount of daytime hours (15 hours and 26.5 minutes for Toronto) and minimizing the night-time hours – making stargazers a bit sad. (At the winter solstice in December, Toronto will experience only 8 hours and 55.7 minutes of daytime.) For the Southern Hemisphere, the start of each season is offset by six months because the Earth’s southern polar axis leans the opposite way from the northern one, like a teeter-totter.

The sun’s trip across the sky takes longer because the points on the horizon where the sun rises and sets will also reach their most northerly azimuths on Thursday. At the latitude of Toronto, the sunset position at the June and December solstices varies by 67 degrees! That’s why the best windows in your house to catch the sunrise or sunset may change through the year – or why the rising sun might shine on your sleepy face for certain weeks of the year.

Just as the beam of a flashlight is strongest when pointed directly towards a wall, and weaker when held obliquely, the higher sun’s light is more intense (more watts per square metre, to be technical). More hours of more concentrated sunlight translates to more solar energy delivered and warmer days! It is NOT the case, as some people think, that we are warmer in summertime because we are closer to the sun. That event, called perihelion, actually happens in early January every year! Moreover, the Earth is now only two weeks away from reaching its greatest distance from the sun, or aphelion, for this year, which will occur on July 5.

The place on Earth where the sun is shining directly overhead at local noon is called the subsolar point. As the Earth completes its full rotation in 24 hours, the subsolar points form a ring at latitude 23.44° N known as the Tropic of Cancer. (The December solstice places the sun above the Tropic of Capricorn.) In antiquity, when the phrase was coined, the sun resided in those constellations on the two solstices. The slow wobble (or precession) of the Earth’s axis of rotation shifts the celestial positions of the sun at the solstices and equinoxes, and varies the precise latitude of the two tropics over time.

Astronomically, the sun will reach its greatest northern declination and its greatest angle from the celestial equator on the summer solstice. Ancient astronomers noticed that, every six months, the sun temporarily stopped varying its declination, the value in degrees that astronomers use to describe a celestial object’s location north or south of the equator. The sun was no longer shifting north or south compared to the fixed stars while it continued to slide east along the ecliptic. They coined the name solstice, from the Latin expression sol sistere, ”the sun is standing still”. As I mentioned above, they could easily measure declination changes by recording the daily length of noon-day shadows.

Even though the solar system runs like clockwork, the dates on which each season begins every year vary a little because there are 365 days plus 5 hours and 48 minutes in a solar year. We stop that extra quarter day from messing up our calendars by using leap years to wipe away the drift every four years.

For our friends in the Southern Hemisphere, the June solstice signals the sun’s lowest noon-time height for the year and marks the start of their winter. We astronomers in the Northern Hemisphere eagerly await the June solstice because, after Thursday, the nights will start to lengthen. More stars!

Stars to Wish Upon

Venus’ brilliance often makes it the first “star” to come out at night, but it won’t be visible in evening until later this summer. If you want to wish upon the first star you see, then you’ve got two to choose from in June – even with a bright moon around!

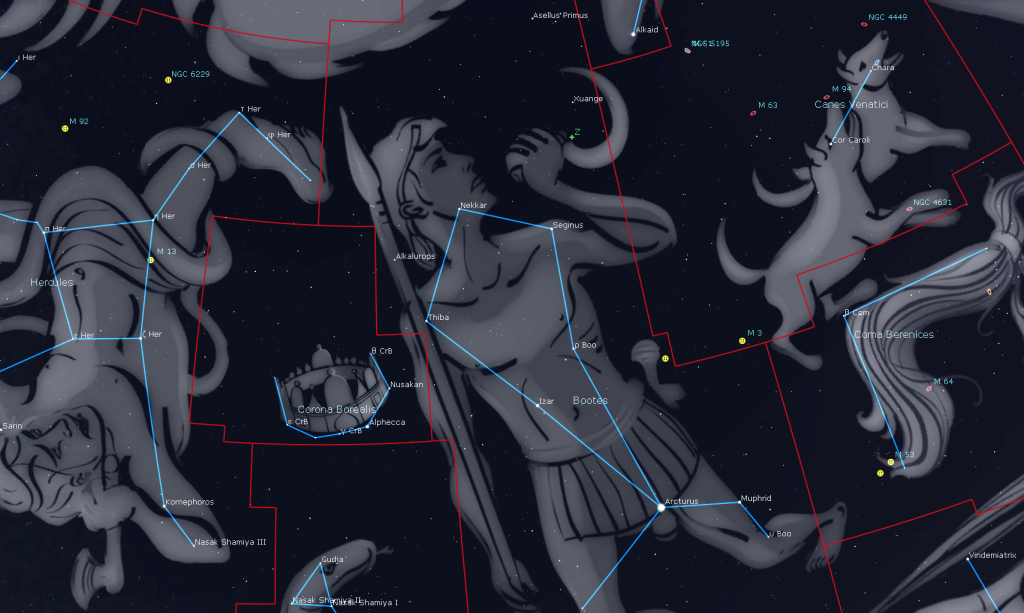

As the post-sunset sky darkens, cast your gaze high in the southern sky to spot yellow-orange Arcturus also known as Alpha Boötis. You can’t miss it! At magnitude -0.15, it’s not only the brightest star in the constellation of Boötes (the Herdsman), but also the fourth brightest star in the entire night sky worldwide. Only our sun and Sirius are brighter for mid-Northern latitude skywatchers. Arcturus is a “neighbour” of ours. It’s only 37 light-years away from the sun.

Arcturus sparkles with that colour because it is just passing middle-age for a star, starting on its way towards the red supergiant stage. In Chinese, Arcturus is known as Dà Jiǎo xīng 大角星, “Great Horn Star”, part of the huge Azure Dragon of the East, which stretches from Boötes and Virgo on the west to Scorpius and Sagittarius on the east. The star Antares marks his heart.

All the stars within our Milky Way galaxy are in motion, jostling about as they orbit the galactic centre every quarter of a billion years or so. Some stars move faster, or are located closer to us – so they exhibit a greater apparent motion compared with the surrounding stars. Astronomers call this phenomenon proper motion. That’s why star charts need to be updated from time to time. Arcturus occupies the belt-buckle of the herdsman. It has a very high proper motion southward. In a few thousand years, the herdsman’s legs will be bent upwards with Arcturus below his knees!

You will probably spot Arcturus first because it will be so high in the sky at dusk. But if you happen to be facing east, you might see the equally bright star Vega, in Lyra (the Harp) first. Vega is the next brightest star in the sky after Arcturus. Astronomers use something called the magnitude scale to indicate the brightness of objects. The star Vega anchors the scale at magnitude 0.0. Each integer higher reduces the brightness by 2.5 times, and each integer lower increases the brightness by the same factor. Polaris, the North Star, shines at magnitude 1.95, which is 6.3 times fainter than Vega. A magnitude step of 0.5 changes the brightness by about 50%.

Before long, you’ll catch sight of another bright (magnitude 1.25) star named Deneb, the tail of Cygnus (the Swan) sparkling to the lower left of Vega. Vega and Deneb are the first corners of the Summer Triangle asterism to appear. The third corner star Altair, will be just clearing the eastern treetops. Although brighter than Deneb, Altair’s brilliance will be suppressed by the extra atmosphere we see it through this early in the evening during June.

Arcturus means “Guardian of the Bear” in Greek, because it rises after Ursa Major (the Big Bear), which sits to its upper right (celestial west). The darkening sky will reveal the seven prominent stars of Ursa Major’s Big Dipper asterism overhead. Meanwhile, reddish Antares “the Rival of Mars”, and the heart of Scorpius, will be twinkling low in the south, too. But, by then, you should already have made your wish!

The Moon at Lunistice

At this part of the lunar month, the moon is increasing its angle from the sun every day – causing it to wax in phase and set about 20 minutes later each night. The very bright moon will dominate the night sky this week almost everywhere on Earth. I say “almost” because if your latitude on Earth is north of about 55° N, you will not experience any night time! And the moon won’t clear the horizon at all at extreme northern latitudes.

Today (Sunday afternoon, June 16) in the Americas, the waxing gibbous moon will rise in mid-afternoon and ascend the southeastern sky until dusk. Once the sky darkens in late evening, look for Spica, the brightest star in Virgo (the Maiden), twinkling several finger widths to the moon’s right (or 3 degrees to its celestial WNW). Spica is a hot, white, B1-class star located 250 light-years from our sun. Hours earlier, skywatchers located in the region northeast of the Black Sea can use binoculars and backyard telescopes to watch the moon cross in front of (or occult) Spica.

On Monday and Tuesday, the moon will travel through Libra (the Scales), but it will largely outshine that constellation’s stars. In the lower part of the southern sky after dusk on Wednesday, the nearly full moon will shine in western Scorpius, between that constellation’s brightest star, reddish Antares, and the up-down row of small white stars that form the scorpion’s claws, named Jabbah or Nu Scorpii, Graffias or Acrab, Dschubba, Pi Scorpii, and Iklil or Rho Scorpii. A backyard telescope at high magnification will reveal that Nu Scorpii, Graffias, and Dschubba are close-together double stars. The next evening, observers north of Papua / New Guinea can watch the moon occult Antares.

The bright moon will spend Thursday night among the southerly stars of Ophiuchus (the Serpent-Bearer), the overlooked thirteenth zodiac constellation. (The sun shines among those same stars in mid-December every year.)

The moon will move into Sagittarius (the Archer) for Friday and Saturday night. It will officially reach its full moon phase on Friday, June 21 at 9:08 pm EDT and 6:08 pm PDT, which converts to 01:08 GMT on Saturday, June 22. The June full moon always shines in or near the stars of southern Ophiuchus or next-door Sagittarius (the Archer).

Thanks to my friend and AmazingSkyGuy Alan Dyer for alerting me to the fact that this full moon will occur near lunistice, or “lunar standstill”. Just as the sun ceases its north-south motion against the stars on the solstices, the moon reaches its own lunistice every 18.6 years. The moon’s orbit is inclined by about 5.1° to the ecliptic. That allows it to wander by up to that distance above (north) or below (south) the ecliptic. (The wandering also prevents us from having solar and lunar eclipses monthly.) Since this full moon will occur only 26 hours after the solstice, when the ecliptic and sun will be highest at local noon, this full moon will be held low in the sky by the low midnight ecliptic. In addition, the moon will be near the maximum excursion south of the low ecliptic. Putting all this together will generate the lowest midnight full moon in nearly 20 years – only 17° above the southern horizon at the latitude of Toronto! The full moon in January, 2025 will be extra high for the same reasons.

Every culture around the world has developed its own teachings about the full moon, and has assigned special names to each moon, which marked time and lit the way of hunters and travelers at night before modern conveniences like flashlights. The indigenous Ojibwe people of the Great Lakes region call this moon Ode’miin Giizis, the Strawberry Moon. For the Cree Nation it’s Opiniyawiwipisim, the Egg Laying Moon (referring to the activities of wild water-fowl). The Mohawks call it Ohiarí:Ha, the Fruits are Small Moon. The Cherokee call it Tihaluhiyi, the Green Corn Moon, when crops are growing. English-speaking, non-indigenous groups commonly use Strawberry Moon, Mead Moon, Rose Moon, Birth Moon, or Hot Moon.

When you face a full moon, the sunlight that illuminates it is coming from directly behind you – the same way the projector in the rear of a cinema lights up the movie screen in front of you. That sunlight is arriving straight-on to the moon’s surface – from directly overhead if you were standing on the moon -so it doesn’t generate any shadows. Since the sun is high in daytime around the June solstice, the June full moon stays low in the night sky. The reverse happens in winter. The late sunsets of June also mean late moon-rises.

Every variation in brightness and colour we see on a full moon is due entirely to the moon’s geology, and not its topography! That means we can easily distinguish the dark, grey basalt rocks from the bright, white, aluminum-rich anorthosite rocks. The basalts overlay the various lunar maria, Latin for “seas” – a term coined because people thought they were water-filled before telescopes revealed otherwise. The maria are giant basins excavated by major impactors early in the moon’s geologic history and then flooded with dark basaltic rock that leaked out of the interior of the moon later in the moon’s geological history.

The much older and brighter parts of the moon are composed of anorthosite rock. Those areas are higher in elevation and are heavily cratered because there is no wind and water, or plate tectonics, to erase the scars of impacts. Lunar scientists use the number of craters in a given location to gauge its age (more craters means older). By the way, the highlands’ bright, white appearance is produced by sunlight reflecting off of the crystals the rock is made of – the same sort of big crystals you can find in the polished granite countertops in Earth’s kitchens. And yes, there are coloured rocks on the moon.

Some of the violent impacts that blasted craters in the highland regions also threw bright streams of ejected material far outward and onto the darker maria. We call those streaks lunar ray systems. Some rays are thousands of km in length – like the ones emanating from the very bright crater Tycho in the moon’s southern central region. Use your binoculars to scan around the full moon for the smaller ray systems everywhere!

There are also places where maria craters have thrown dark rays onto white rocks. And, since the dark basalt overlays the white, older rock beneath them, you can find lots of craters where a hole has been punched through the dark rock, producing a white-bottomed crater! Any size of telescope will show them. Just pan around.

Several of the maria link together to form a curving chain across the northern half of the moon’s near-side. Mare Tranquillitatis, where humanity first walked upon the moon, is the large, round mare in the centre of the chain. You can plainly see that this one is darker and bluer than the others, due to its basalt being enriched in the mineral titanium. That’s one of the reasons why Apollo 11 was sent to land in it. (The other was that it is close to the moon’s equator, making the orbital mechanics easier.)

By the way, Earth-bound telescopes – even the largest ones – cannot see the items left by the astronauts on the moon. When the air is particularly steady, the smallest feature you can see on the moon with your backyard telescope is about 2 to 6 km across – far larger than any lunar module descent stage, which are only about 4 metres across. Only cameras on spacecraft in orbit around the moon can photograph the Apollo astronauts’ footprints, lunar rover tracks, and equipment. The upcoming Artemis missions to the moon will focus on the lunar polar regions where water frozen in permanently shadowed craters can be harvested.

While the moon is almost fully illuminated this coming weekend, use your telescope to look at the dark stains left behind by extinct volcanoes on the moon! Alphonsus is a 110 km wide crater located just south of the moon’s centre, on the upper right shore of Mare Nubium. Any size of telescope will reveal a triangle formed by numerous dark spots on the crater’s floor near its left and right rims. Those are ash deposits. Another crater with similar markings is Atlas, which sits in the northern region of the moon, about halfway between the northern shore of Mare Serenitatis and the edge of the moon.

Next Sunday night the waning, but still bright, gibbous moon will outshine the faintish stars of Capricornus (the Sea-Goat) to its left (or celestial east).

The Planets

With another week behind us, we have only three weeks to wait before Saturn starts to rise in the east before midnight. Mercury will become visible over the western horizon after sunset starting next week, and Venus will begin an eight-month stint as the “evening star” as July begins. For now, you’ll need to head outside between the wee hours and dawn if you want to see any of the planets.

This week, the medium-bright, yellowish dot of Saturn will rise around 1:10 am local time and then clear the rooftops in the east about an hour later. You’ll be able to see Saturn until almost sunrise. The planet will spend the next 10 months among the stars of eastern Aquarius (the Water-Bearer). Binoculars will show you an up-down row of five stars to Saturn’s right (or celestial west). A trio of blue-white stars huddling to Saturn’s lower right are named Psi1,2,3 Aquarii (or ψ1,2,3 Aqr). Several golden-coloured stars, including Phi and Chi Aquarii are spread out above them, to Saturn’s right.

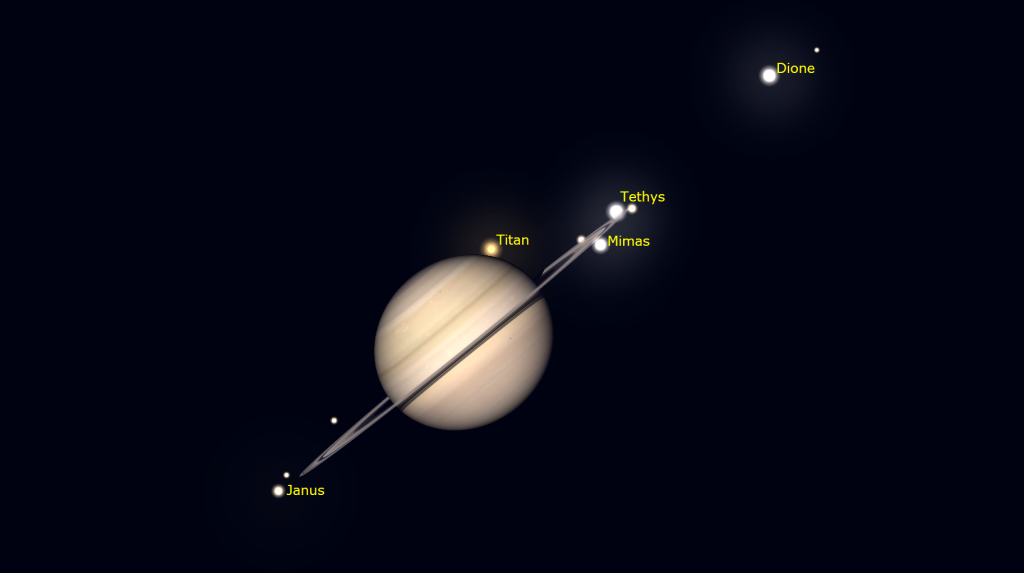

Saturn’s rings, which will effectively disappear when they become edge-on to Earth next March, already look very narrow against the planet’s globe. Good binoculars can hint at Saturn’s rings and any telescope will show them. For telescope-owners, Earth’s perspective of the Saturn system this year and next will produce frequent transits of Saturn’s moons and their black shadows across its disk. On Saturday morning, folks with good quality telescopes can watch Saturn’s largest moon, named Titan, approach Saturn and become occulted by the planet around 07:50 GMT. The dots the moons Tethys and Mimas might be glimpsed at the tip of Saturn’s rings. Brighter Dione will be farther from the planet in the same direction.

The distant planet Neptune will rise about 20 minutes after Saturn. The blue planet will spend this year in western Pisces (the Fishes), a generous fist’s width to the lower left (or 11° to the celestial ENE) of Saturn. Neptune will also be located a bit more than a thumb’s width to the upper left (or 2° north) of a medium-bright star named 27 Piscium. They’ll share the view in binoculars. Other less-brilliant stars nearby named 29 Piscium, 24 Piscium, and 20 Piscium will help guide you to Neptune with a backyard telescope or good, strong binoculars. You’ll need to look at Neptune while the sky is dark (before about 4 am local time).

Reddish Mars will rise by 2:50 am local time and remain in sight until dawn. If the sky is still dark, the brightest stars of Aries (the Ram) will twinkle above Mars. Mars will look a little brighter than Saturn. In a telescope, Mars will display a small, ruddy disk. Its position on the far side of the sun from Earth will keep the planet looking small until later this year.

Although Uranus will rise next, at about 3:35 am, the brightening sky will make seeing the planet harder. To aid in your search, seek out the pretty, prominent Pleiades star cluster in your binoculars. Uranus will be positioned a palm’s width to its right. Folks with an unobstructed horizon towards the ENE can look for far brighter Jupiter after it rises around 4:10 am local time. Be sure to turn all optical aids away from the eastern horizon before the sun rises.

The inner planets Venus and Mercury will be hidden by the sun’s glare this week – but they’ll return to view soon.

Public Astronomy-Themed Events

Every Monday evening, York University’s Allan I. Carswell Observatory runs an online star party – broadcasting views from four telescopes/cameras, answering viewer questions, and taking requests! Details are here. They host in-person viewing on the first clear Wednesday night each month. Other Wednesdays they stream views online via the observatory YouTube channel. Details are here.

Space Station Flyovers

Aside from a few poor, early morning passes, the ISS (or International Space Station) will not be visible gliding silently over the Greater Toronto Area this week.

Keep your eyes on the skies! I love getting questions and requests. Send me some!