Romantic Night Sights While the Waxing Moon Dances with Jupiter, Shows Some L-O-V-E, and Finds the Football!

Adrien Klamerius took this image of the Heart (upper left) and Soul (lower right) nebulas in Cassiopeia, also known as IC 1805 and IC 1848, respectively. The Double Cluster as at top centre. The area of sky covers about 10 degrees, or a fist diameter. NASA APOD for Sep 24, 2016

Hello, Night Sky Lovers!

Here are your Astronomy Skylights for the week of February 11th, 2024 by Chris Vaughan. Feel free to pass this along to your friends and send me your comments, questions, and suggested topics. You can also follow me on Twitter as @astrogeoguy! Unless otherwise noted, all times are expressed in Eastern Time. To subscribe to these emails please click this MailChimp link.

If you’d like me to bring my Digital Starlab portable inflatable planetarium to your school or other daytime or evening event, or deliver a session online, contact me through AstroGeo.ca, and we’ll tour the Universe, or the Earth’s interior, together! My book with John A. Read entitled 110 Things to See With a Telescope is a guide to viewing the deep sky objects in the Messier List – for both beginners and seasoned astronomers. DM me to order a signed copy!

The moon will return to the evening sky this week to spark some romance and to dance with Jupiter on Valentine’s Eve and then sporting a lunar X and the letters L-O-V-E. Prom planets royalty Venus and Jupiter will dominate the sky before dawn and dusk, respectively, and I share some love-themed sights for star-lovers. Read on for your Skylights!

The Moon Shows an X and some L-O-V-E!

The moon will spend this week shining in the evening sky worldwide. Its waxing crescent is always visible during times that are convenient for sky-watchers of any age. Moreover, as we approach the spring months in the Northern Hemisphere, the more upright angle of the ecliptic lifts the evening moon higher into the sky, where telescopes and binoculars can reveal its fascinating details most clearly.

There is plenty to see on the moon for the pure joy of it, but if you have ever planned to embark on one of the lunar observing programs offered by the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada, the Astronomical League in the USA, or others, this is best time of year to begin! The information page for the RASC moon programs is here. I’ve recently completed RASC’s much more detailed Isabel Williams Lunar Observing Program. It’s amazing what you can see when given some guidance in what to look for!

Tonight (Sunday) the slender crescent of the young moon will appear low in the western sky for a while after sunset. The sky will darken enough to see some stars by the time the moon sets around 8 pm local time. Watch for Earthshine, too. Sometimes called the Ashen Glow or the Old Moon in the New Moon’s Arms, the phenomenon is visible within a day or two of new moon, when sunlight reflected off Earth and back toward the moon slightly brightens the unlit portion of the moon’s Earth-facing hemisphere. It’s especially apparent in the spring evening and autumn morning.

The moon will set relatively early for the first part of this week, allowing us to view the best objects of the winter sky the rest of the night. I’ll share some suggestions to seek out below.

For those of us at mid-northern latitudes the moon will set about 80 minutes later each night this week. That’s due to its increasing angle from the sun – about 14 degrees per day – as the moon orbits Earth. The moon will also wax in illuminated phase. The curved, pole-to-pole boundary that divides the moon’s lit and dark hemispheres will steadily migrate across the moon’s Earth-facing side, altering the balance between lit and dark. By the way, the moon is always half illuminated (except during a lunar eclipse), so when we see a crescent moon in the sky, the majority of the moon’s far side is being lit up by sunshine. That’s why astronomers don’t use “the dark side” to refer to the half of the moon that we never see from Earth. We prefer to say “the far side”.

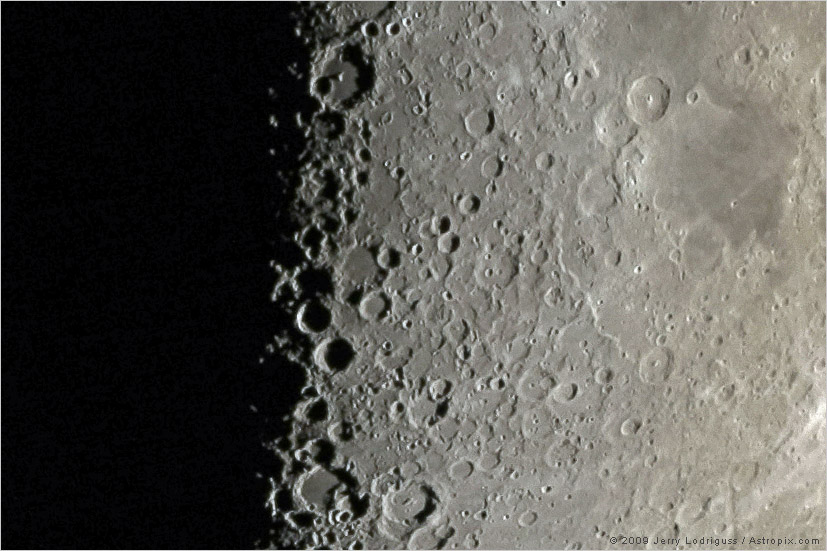

Along the terminator line the sun is rising on the moon. All of the rays of sunshine striking the moon beside the terminator will be nearly horizontal, casting long shadows from even the smallest raised feature. Meanwhile, the depressed crater floors become pools of inky blackness. That strip is the best portion of the moon to look at in your binoculars or backyard telescope. Since the terminator is constantly on the move, you can watch for differences in illumination over an hour or two – and definitely from one night to the next. When craters are partially in shadow, we can use the profile of their shadow line to work out the shape of the crater’s bowl (curved or flat-bottomed) and which parts of the crater’s rim are highest.

On Monday night, the dark oval-shape of Mare Crisium will be highlighted within the moon’s lit crescent. It’s actually round, but we see it fore-shortened because it sits near the moon’s eastern limb, which is curving away from us. As the nights pass more of the moon’s grey maria, which are actually giant craters that have been filled in with dark basalt rock, will move into the light. The maria cover about 31% of the moon’s Earth-facing side, but only about 1 % of its far side. It’s likely that the intense heat of young Earth and our planet’s strong gravitational attraction, encouraged the upwelling of the basalt from the moon’s interior on the side facing us.

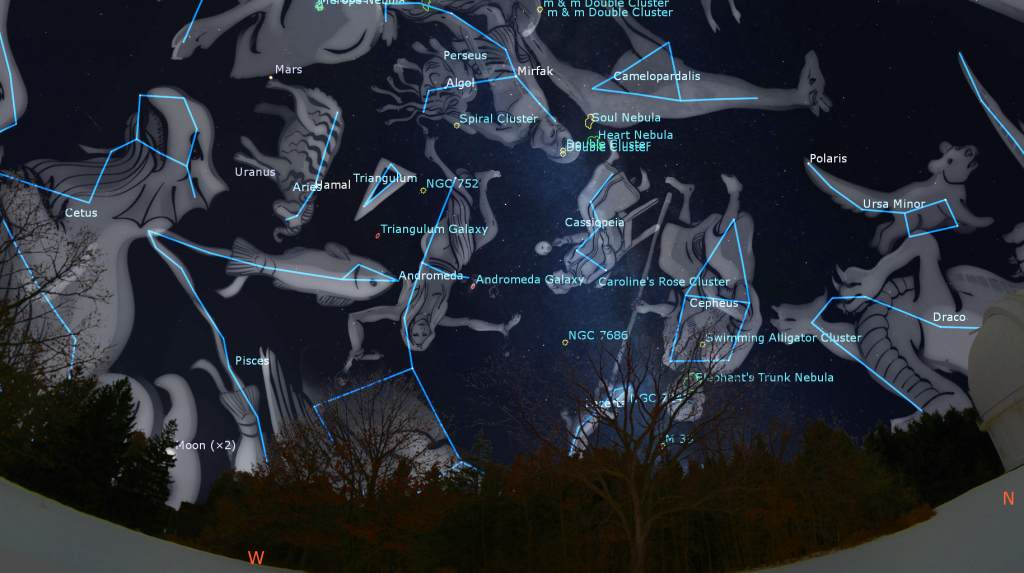

The moon will spend Monday and Tuesday crossing the stars of Pisces (the Fishes), but you should also be able to glimpse the moon in the blue daytime sky from late morning onward. Wednesday’s waxing crescent moon will be on a Valentine’s date with the bright planet Jupiter along with the stars of Aries (the Ram). The planet and moon will rise in late morning, cross the sky all day long, and then set in the west around midnight. Binoculars-users can try to spot Jupiter’s small pale disk positioned less than a fist’s diameter to the moon’s lower left in bright daylight – but be sure not to point the lenses anywhere near the sun.

The moon’s eastward motion of about one lunar diameter per hour will carry it steadily closer to Jupiter. In late afternoon, they’ll be arranged left-right and just close enough together to share the view in binoculars. They’ll make a pretty sight for unaided eyes and for cameras as the sky is darkening. If Valentine’s night is cloudy, watch for their make-up date on Thursday night, albeit a less cosy one. That night, the blue-green, magnitude 5.8 speck of Uranus will be positioned only a few finger widths to the lower left (or 3 degrees to the celestial south) of the nearly half-illuminated moon – easily close enough for them to share the view in binoculars.

On Friday morning, February 16, the moon will complete the first quarter of its orbit around Earth, measuring from the previous new moon, at 10:01 am EST, 7:01 am PST, or 15:01 GMT. At first quarter, the 90 degree angle formed by the Earth, sun, and moon will cause us to see our natural satellite as a half-moon with its eastern hemisphere illuminated. The moon will look a little less than half-illuminated on Thursday night, and a little more than half-illuminated on Friday night. (Lunar phases occur independently of Earth’s rotation.)

Friday night’s moon will be passing very close to the Pleiades star cluster in Taurus (the Bull). Observers in Europe and Africa will see the stars of that cluster sprinkled just to the right (or celestial west) of the moon.

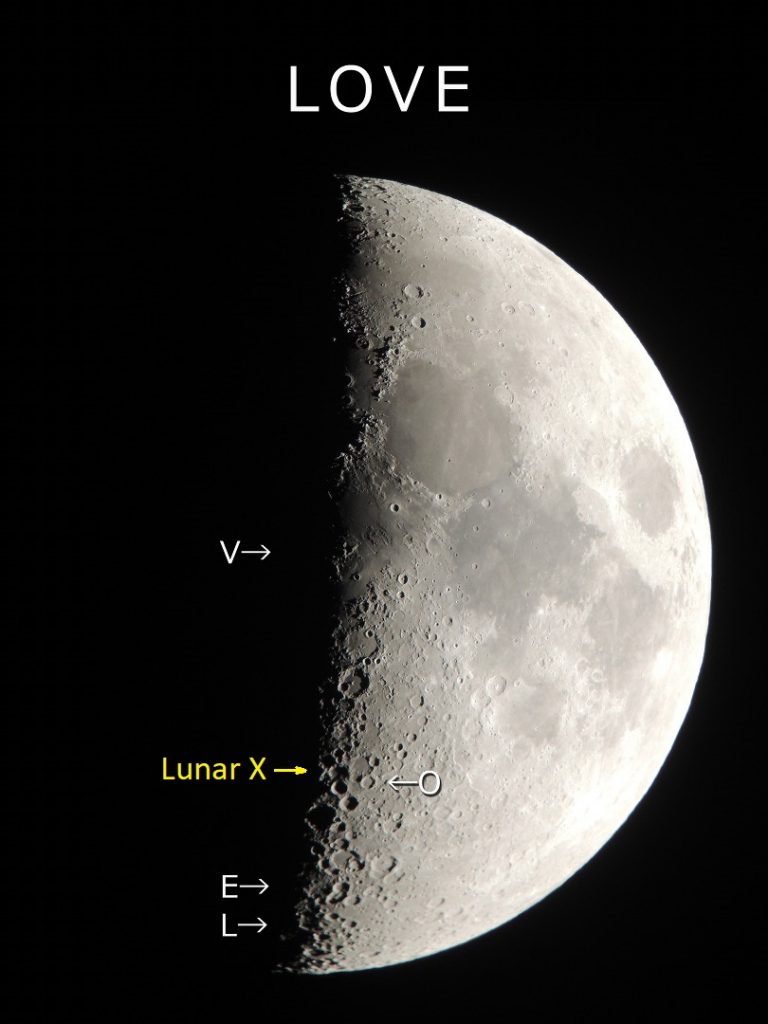

Several times a year, for a few hours near its first quarter phase, a feature on the moon called the Lunar X becomes visible in powerful, tripod-mounted binoculars and backyard telescopes. Luckily, the X will appear on Friday evening, February 16 in the Americas! When the rims of the craters Purbach, la Caille, and Blanchinus are illuminated from a particular angle by the sun, they form a small, but very obvious X-shape. The phenomenon is an example of pareidolia – the tendency of the human mind to see familiar objects when looking at random patterns. The Lunar X is located near the terminator, about one third of the way up from the southern pole of the moon (at lunar coordinates 2° East, 24° South). A prominent round crater named Werner sits to its lower right (or lunar southeast).

When the sun’s light first touches those craters the X will be indistinct. The shape will intensify to peak visibility at around 7:30 pm EDT on Friday, and then fade when the surrounding terrain becomes illuminated an hour or two later. The event will begin during waning daylight for observers in the eastern Americas – but you can observe the moon in a telescope during daytime, as long as you take care to avoid the sun. The pattern will be visible anywhere on Earth where the moon is shining, especially in a dark sky, between 22:00 on February 16 and 03:00 GMT on February 17.

During a Lunar X event, you can also look for the Lunar V and the Lunar L. The “V” is produced by combining the small crater named Ukert with some ridges to the east and west of it. It is located a short distance above the moon’s equator at lunar coordinates 1.5° East, 8° North. For a further challenge, see if you can see the letter “L” down near the moon’s southern pole. Its position is to the southwest of three prominent and adjoining craters named Licetus, Cuvier, and Heraclitus, which resemble Mickey Mouse’s head and ears. Some people claim they can see a letter-E on the moon during the Lunar X period, too. Then, by picking a round crater along the terminator to serve as the “O”, you can spell L-O-V-E! While you are looking at the moon, watch for subtle wrinkles snaking across the lit half of Mare Imbrium, the giant basin in the northern portion of the moon.

Friday will also see the waxing gibbous moon starting its monthly trip across the Winter Football. The Winter Football, also known as the Winter Hexagon and Winter Circle, is an asterism composed of the brightest stars in the constellations of Canis Major, Orion, Taurus, Auriga, Gemini, and Canis Minor – specifically Sirius, Rigel, Aldebaran, Capella, Castor & Pollux, and Procyon. The hexagon is visible during evenings from mid-November to spring every year. Viewed during evening from mid-Northern latitudes, the huge pattern will stand upright in the southern sky – stretching from about 30 degrees above the horizon to overhead with bright Capella at the top. The ecliptic bisects the asterism, allowing the moon and planets to cross it frequently. The Milky Way passes vertically through those stars, but you won’t see its faint glow while the waxing gibbous moon journeys through the giant shape until Tuesday.

The Lakota people of central North America saw a modified version of the asterism called Cangleska Wakan “the Sacred Hoop”. They include the Pleiades cluster, which they call Wicincala Sakowin “Seven Little Girls”. The Sacred Hoop encloses Tayamni, an animal composed of the Pleiades (its head), parts of Orion (its spine and ribs), and the star Sirius (its tail). The boxy stars of Gemini become Mato Tipila “the Bear’s Den”. To them the Sacred Hoop is the stellar embodiment of the “unending circle of time, space, matter, and spirit.” I shared a photo of it here.

Valentine’s Night Treats

While none of the official constellations are heart-shaped, there are some romantic duos in the stars that you can see with your unaided eyes on Valentine’s Day night – even with a bit of moonlight.

If you look about halfway up the western sky after dusk you’ll see the stars of Princess Andromeda extending upwards from the top corner of the big square of Pegasus (the Flying Horse). Andromeda’s hero, and eventual husband, Perseus is the constellation directly above her. Its centre is marked by the very bright star Mirfak. Between those lovers, and a few fist diameters to their right (or 30° to the celestial northwest of them), are her parents’ constellations, w-shaped Queen Cassiopeia and boxy King Cepheus. This year, Jupiter will gleam off to their left.

To celebrate fraternal love, we have the constellation of Gemini (the Twins), which is located in the eastern sky to the upper left (or celestial northeast) of Orion (the Hunter). The two medium-bright stars Pollux (the lower one) and Castor (the upper one) mark the heads of the two brothers. Note that Pollux is a wee bit brighter and warmer in colour than Castor. Viewed through your telescope, Castor splits into a nice double star.

For a different type of devotion, we can highlight Orion the hunter’s faithful companion Canis Major (the Big Dog). Canis Major forever and faithfully follows his master around the sky – although he might be more interested in chasing Lepus (the Hare), the constellation that sits to his west, below Orion. The big dog’s stars are distributed around their brightest member, Sirius, also known as the Dog Star (and Alpha Canis Majoris). On mid-February evenings, Sirius reaches its highest point over the southern horizon at around 9:30 pm local time. Sparkling like a diamond, Sirius is a hot, white, A-class star located only 8.6 light-years from Earth – part of the reason for its brilliance. For mid-northern latitude observers, Sirius is always seen in the lower third of the sky, through a thicker blanket of refracting atmosphere. This causes the strong twinkling and flashes of colour the Dog Star is known for.

Look less than a finger’s width to the lower right of the bright star Alnitak – the star at the eastern, left-hand end of Orion’s Belt – for a medium-bright star named Sigma Orionis or σ Ori. When viewed in powerful binoculars or a backyard telescope, you’ll see that Sigma Orionis is in the middle of a pretty little group of about 10 stars arranged in a dart shape – like Cupid’s Arrow!

Beside Orion, on his eastern (left) side, and above Canis Major, is the constellation of Monoceros (the Unicorn). Its stars are mainly of medium and low brightness – but it sits squarely astride the Milky Way and contains some delightful sights! The Rosette Nebula (also known as NGC 2244) is a beautiful rose-shaped cloud of reddish gas with a clump of bright little stars in its centre. It is located about a fist’s diameter to the left of Orion’s shoulder star Betelgeuse. The Rosette is visible in binoculars, but only long-exposure photos will reveals its colourful rose.

A little star named Theta Canis Majoris that shines a palm’s width to the upper left of Sirius marks the doggy’s nose! If you draw an imaginary line from Sirius to Theta and then double its length, you’ll arrive at a small open star cluster named Messier 50, also known as the Heart-Shaped Cluster and NGC 2323. The cluster is visible in binoculars – but try viewing it through your telescope. I don’t think that the heart shape is all that obvious – but the cluster of mainly white stars features the special treat of a bright, golden star at its lower edge.

Cassiopeia (the Queen) hosts the Heart Nebula, also known as the Valentine Nebula and IC 1805. It’s a truly beautiful object located 2,500 light-years away from us. This nebula and its companion the Soul Nebula (IC 1848) are located between Perseus and Cassiopeia – about three finger widths to the right of the Double Cluster. It’s too faint to see unless the sky is very, very dark – but many lovely photographs of it have been published. A faint, but rich star cluster named Caroline’s Rose (NGC 7789), named for the renowned woman astronomer Caroline Herschel, is a few degrees below the bottom stars of Cassiopeia.

Finally, to celebrate your favorite someone, locate and view their Birthday Star. That’s a star that is located at the same distance from Earth (expressed in light-years) as that person’s age in years. In other words, the light you see now started its journey towards us at the time they were born. Visit this page and scroll down the list to find birthday stars for different years old – or use this page to enter a birth date. Then you can look for that star in the night sky – if it happens to be visible at this time of year from your location. It’s fun! And the stars for kids’ ages tend to be the closest and brightest stars in the night sky – and easy to see, even from the city.

Happy Valentine’s Day!

The Planets

The slender crescent moon that shines above the western horizon tonight (Sunday) after sunset will be above Saturn and below Neptune – but those two planets are not worth chasing when so close to the sun. Don’t worry – they’ll be back in a few months. Saturn will pass the sun at solar conjunction at the end of February and then enter the eastern pre-dawn sky.

For about another month, Jupiter will dominate the evening sky. As the sky begins to darken after sunset, the brilliant planet will appear high in the south-southwestern sky. If you have any size of telescope, aim it at Jupiter as soon as you can see the planet. Bright planets can show more detail in a twilight sky. You’ll get great views of Jupiter in a telescope until about 10:15 pm local time – and less so as it gets ready to set towards midnight. The planet will be surrounded by the stars of Aries (the Ram). The crescent moon will shine near Jupiter on Wednesday and Thursday night.

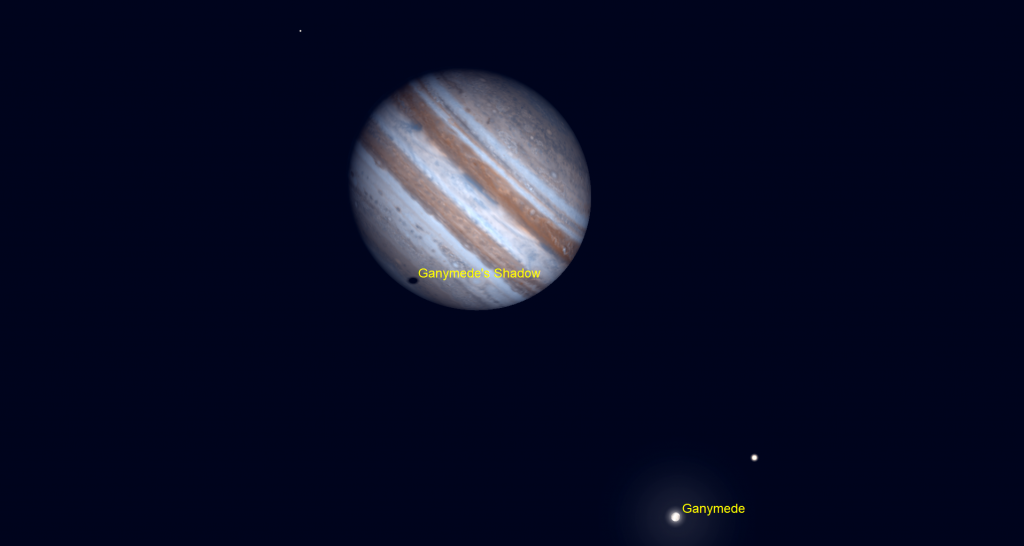

Any decent pair of binoculars can show you Jupiter’s four largest Galilean moons lined up on both sides of the planet. Named Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto in order of their orbital distance from Jupiter, those moons complete orbits of the planet every 1.7, 3.6, 7.2, and 16.7 days, respectively. If you see fewer than four moons, then one or more of them is crossing in front of or behind Jupiter, or hiding in Jupiter’s dark shadow – or two of the moons are very close together or occulting one another. In the Americas, the moons will all gather to Jupiter’s west on Monday and to the planet’s other side on Friday.

A small telescope can show you Jupiter’s dark belts and light zones, which are aligned parallel to its equator. With a better grade of optics, Jupiter’s Great Red Spot, a cyclonic storm that has raged for hundreds of years, is visible for several hours when it crosses the planet every 2nd or 3rd night. For observers in the Americas, the GRS will cross Jupiter’s disk in mid-evening Eastern Time on Wednesday and Friday. It’ll appear late tonight (Sunday), Tuesday, Friday, and next Sunday night (with Ganymede’s shadow). The spot has been rather a pale pink in colour for some time now. If you have any coloured filters or nebula filters for your telescope, try enhancing the spot with them.

From time to time, the small, round, black shadows cast by Jupiter’s Galilean moons become visible in amateur telescopes when they cross (or transit) the planet’s disk. For those in the Americas, Ganymede’s large shadow will cross Jupiter’s southern polar region on Sunday, February 11 from 5:33 to 7:05 pm EST (or 17:33 to 00:05 GMT). Europa’s tiny shadow will cross Jupiter on Wednesday, February 14 from 9:55 pm to 12:05 am EST (or 02:55 to 05:05 GMT on Thursday). Ganymede’s shadow will cross the southern latitudes again, with the red spot this time, next Sunday, February 18 from 9:35 to 11:05 pm EST (or 02:35 to 04:05 GMT on Thursday). (These times may vary by a few minutes, and other time zones of the world will have their own crossings.)

Blue-green Uranus is an hour behind Jupiter on the ecliptic, in the eastern side of Aries (the Ram). The magnitude 5.7 planet is normally quite easy to see in binoculars and backyard telescopes, but this moon will make that harder. Look for Uranus about one fist diameter to Jupiter’s upper left (or 10° to its celestial ENE). The bright Pleiades star cluster will sparkle a generous fist’s width above Uranus (or 12° to its celestial northeast). The three bright stars of Orion’s Belt roughly point at Uranus, too.

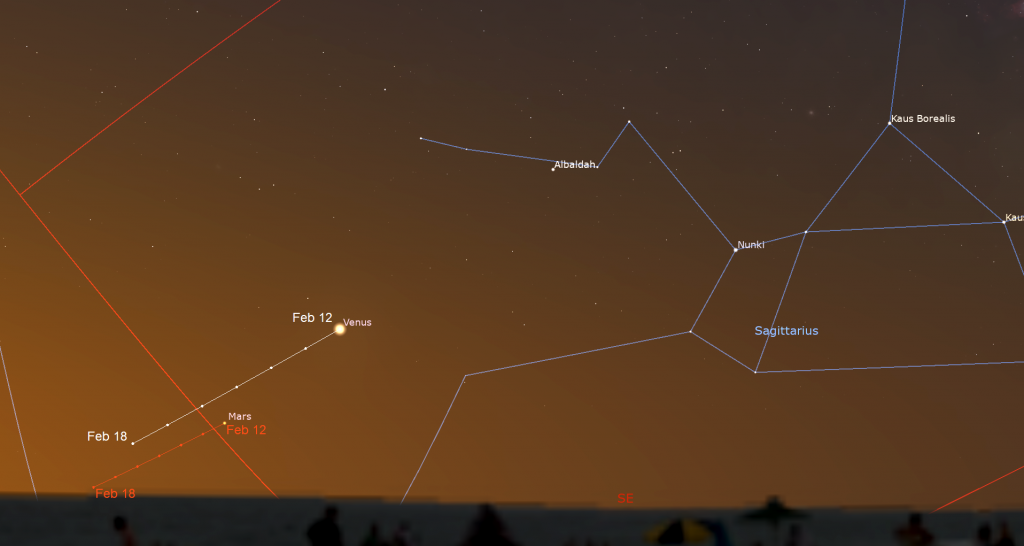

To see any other planets, you’ll need to head outside before sunrise, which will arrive around 7:20 am local time in Toronto. The sky will already be getting light when extremely bright Venus rises at about 6 am local time. The planet is rapidly swinging toward the sun, so it will soon be gone from view. This week Venus will shift east, from eastern Sagittarius (the Archer) to Capricornus (the Sea-Goat), by more than an outstretched palm’s width.

Much fainter Mars will be located to Venus’ lower left (or celestial east). Mars’ motion away from the sun and Venus’ towards it will move them toward one another. On Monday morning, Mars will be several finger widths (or 4.2°) to Venus’ lower left. Next Sunday morning, their separation will close to less than half of that. They’ll kiss in a close conjunction next week.

Public Astronomy-Themed Events

Every Monday evening, York University’s Allan I. Carswell Observatory runs an online star party – broadcasting views from four telescopes/cameras, answering viewer questions, and taking requests! Details are here. They host in-person viewing on the first clear Wednesday night each month. Other Wednesdays they stream views online via the observatory YouTube channel. Details are here.

On Friday, February 16 from 7 to 9 pm EST, the in-person Astronomy Speakers Night program at the David Dunlap Observatory in Richmond Hill, Ontario will feature Dr. June Parsons. They will speak on JWST and the Search for Life in Unexpected Places.After the presentation, participants will tour the observatory and see a demonstration of the 74” telescope pointed to an interesting celestial object for the visitors to view (weather permitting). More information is here and the registration link is at ActiveRH.

Keep your eyes on the skies! I love getting questions and requests. Send me some!