The Evening Moon Earns a Look, Planets Parade at Dawn and Dusk, and Moonlit Nights Brightest Lights!

On Tuesday evening, January 16, the lunar terminator will fall to the west of three prominent craters Theophilus, Cyrillus, and Catharina and throw into stark relief many other craters in the lunar highlands. The features will be visible in quality binoculars and through any telescope. (from 2024 NASA Lunar Visualization tool)

Hello, Mid-January Stargazers!

Here are your Astronomy Skylights for the week of January 14th, 2024 by Chris Vaughan. Feel free to pass this along to your friends and send me your comments, questions, and suggested topics. You can also follow me on Twitter as @astrogeoguy! Unless otherwise noted, all times are expressed in Eastern Time. To subscribe to these emails please click this MailChimp link.

If you’d like me to bring my Digital Starlab portable inflatable planetarium to your school or other daytime or evening event, or deliver a session online, contact me through AstroGeo.ca, and we’ll tour the Universe, or the Earth’s interior, together! My book with John A. Read entitled 110 Things to See With a Telescope is a guide to viewing the deep sky objects in the Messier List – for both beginners and seasoned astronomers. DM me to order a signed copy!

The waxing moon will be especially nice to view in binoculars and telescopes during evening this week, joining Saturn, Neptune, Jupiter, and Uranus. The inner planets will shine before the sun rises and Mars will lurk below them. I also tour and rank the brightest stars of January. Read on for your Skylights!

The Moon

This week, stargazers around the world will see the moon in the evening sky – but you can still enjoy the January stars and deep sky delights on the first few evenings of the week and in late night until about Thursday. For moon-lovers this will be the best week of the lunar month to appecriate the moon in binoculars or a backyard telescope.

Tonight (Sunday) after sunset, the pretty, young crescent moon will shine in the western sky a palm’s width to the upper left (or celestial east) of Saturn. The grey oval of Mare Crisium, which is actually round, but fore-shortened, will dominate on the sunny side of the curved, pole-to-pole terminator boundary. On Tuesday, the “thicker” moon will be farther from Saturn. Faint Neptune will be positioned just a lunar diameter to the moon’s lower right, but that will be a challenge to see against its glare.

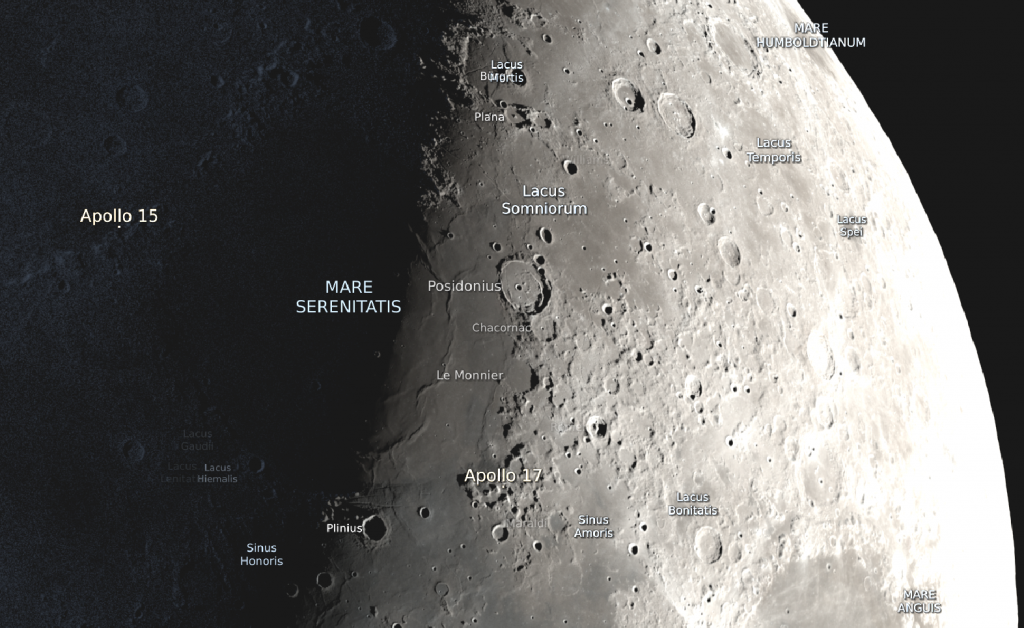

The terminator on Tuesday’s moon will land just to the west of the curved trio of large craters named Theophilus, Cyrillus, and Catharina that formed outside the western edge of round, gray Mare Nectaris. That mare sits to their lower right (or lunar east). You can tell what order those craters were formed in by observing how sharp and fresh Theophilus’ rim appears, and by the way it has partially overprinted neighboring Cyrillus to its lower right (lunar southwest). Under magnification, Theophilus’ terraced rim and craggy central mountain peak are evident. Cyrillus hosts a trio of degraded central peaks inside a hexagonal rim, while much older Catharina’s peak has been submerged, her edges blurred and her floor overprinted by smaller, more recent craters.

Shift your view up to the right, toward the moon’s high northern latitudes and look for subtle wrinkles curving on the dark floor of the dark mare named Serenitatis and the interesting details inside the big, nearly flooded crater named Posidonius that has been formed along the eastern edge of that ocean of basalt. For scale, that crater is about 100 km across.

The moon will complete the first quarter of its 29.53-day journey around Earth on Wednesday, January 17 at 10:53 pm EST or 7:53 pm PST, which converts to 03:53 Greenwich Mean Time on Thursday morning. The moon will rise by noontime and cross the sky all afternoon. Try using your binoculars to see the small pale disk of Jupiter positioned about 1.2 fist diameters to the left of the moon. The duo will certainly become visible after sunset. By the time they set in the west around 1:30 am on Thursday, the moon will be closer to Jupiter.

You can find Jupiter more easily on Thursday afternoon. This time, the planet will be positioned less than two finger widths to the moon’s lower right – close enough for them to appear together in binoculars and telescopes at low magnification. The moon will spend Thursday and Friday within the borders of Aries (the Ram).

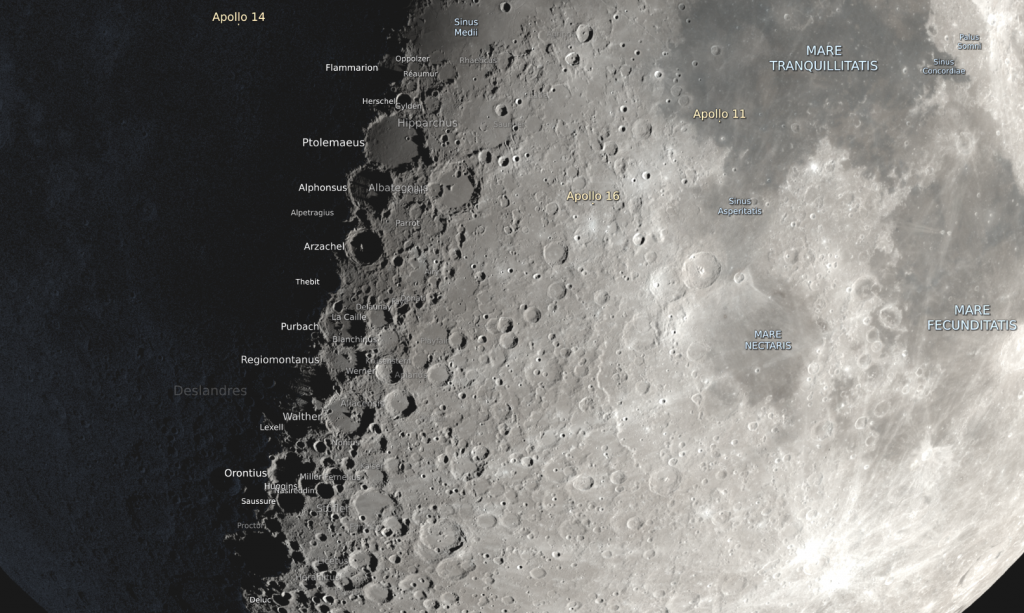

Thursday night will offer a great view of some big craters highlighted near the terminator. Maginus in the southern part of the moon will appear as a dark hollow. Closer to the moon’s equator, look for an up-down trio of connected craters named Ptolemaeus, Alphonsus, and Arzachel. The northernmost crater Ptolemaeus (154 km wide) has been battered by later impacts that confirm its older age. The flat, almost featureless floor has been filled by lava flows, submerging its central peak and elevating its floor. Alphonsus (119 km wide) is older yet and partially filled, allowing its central peak to remain visible. Alphonsus contains a triangle of dark spots that are most prominent when the moon is full – ash deposits from long-ago volcanic venting. Relatively young Arzachel (96 km wide) has an unaltered floor and a terraced rim. A large number of north-south scratches, or lineations, surround those craters – carved by ejecta during the powerful Imbrium Basin impact event. Just south of that trio are another up-down set named Purbach, Regiomontanus, and Walther. Which of those do you think was formed first?

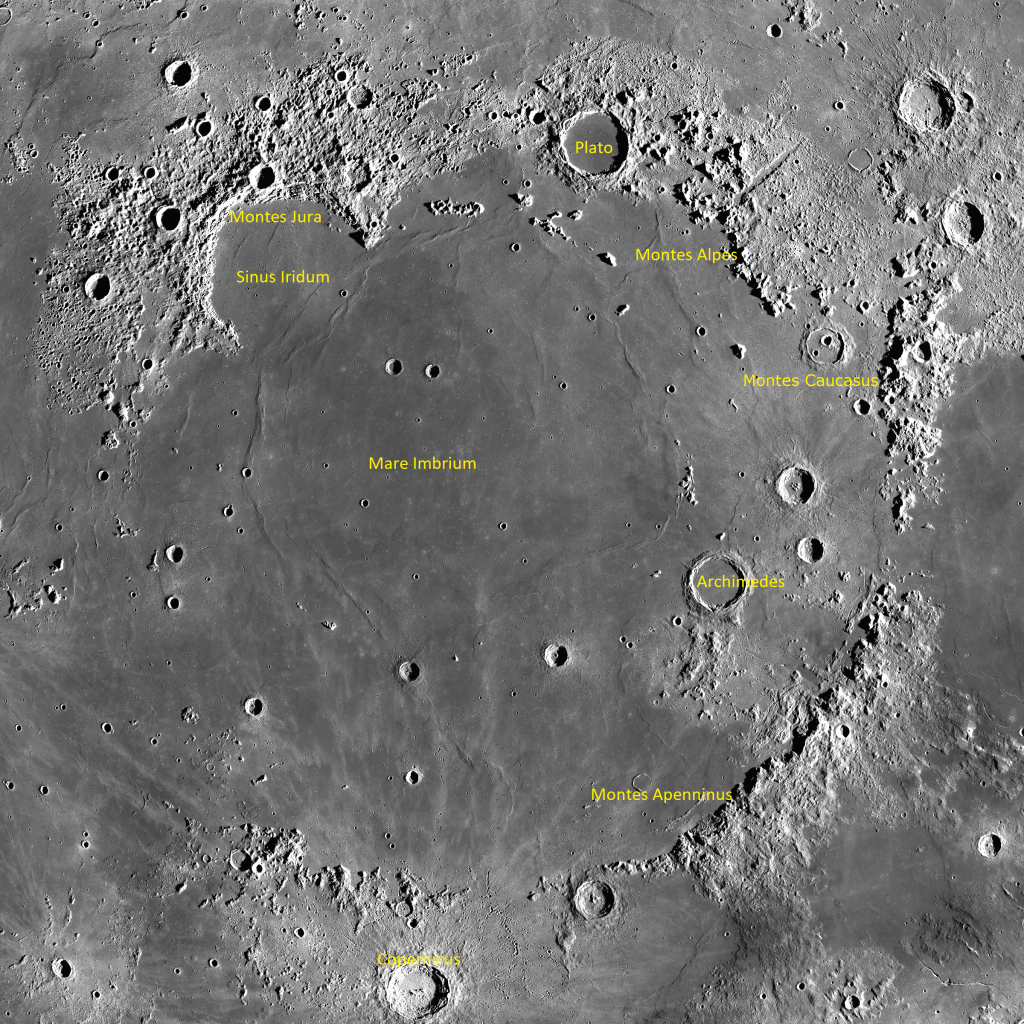

The northern section of Thursday’s moon will be dominated by the eastern semi-circle of the great Imbrium Basin. It is ringed by three spectacular and tall mountain ranges that were pushed up during its formation. The northern arc is the Lunar Alps (or Montes Alpes). The southern arc is the Apennine Mountains (or Montes Apenninus). The less continuous Caucasus Mountain (or Montes Caucasus) range that curves between them is breached where Imbrium connects to Mare Serenitatis. Imbrium’s big central crater Archimedes will be breaking free of the terminator’s dark clutches.

On Friday night, the bright gibbous moon will be shining between Jupiter and the Pleiades star cluster. Sweep your binoculars to the moon’s left to find that glittering patch of stars. Focusing them on the moon again, you can try to spot the star Botein shining just to the moon’s lower right. The planet Uranus will be located several finger widths farther in the same direction as Botein.

On Saturday, our natural night-light will hop east into Taurus (the Bull) and the Pleiades will be located to the moon’s right (or celestial west). The bull’s bright orange eye-star Aldebaran will shine below the moon. Both Friday and Saturday will deliver terrific views of Mare Imbrium under illumination.

On Sunday night, the nearly full moon will begin its monthly trip across the big Winter Hexagon / Football asterism. That night, the curved Jura Mountains bordering Sinus Iridum “the Bay of Rainbows” will catch your attention in binoculars or telescopes. Next, sweep down toward the moon’s southern latitudes to see the spectacular, large crater Gassendi that sits alongside the smooth, dark oval of Mare Humorum. That mare mirrors Mare Crisium in size and position.

The Planets

Jupiter will continue to dominate the evening sky, second only to this week’s moon in brilliance. But the planet you should focus your attention on first after dinner is Saturn, as we only have another week or two to view it well in telescopes. I went into detail about why that is last week.

This week, Saturn’s yellowish dot will pop into view in the lower part of the southwestern sky shortly after sunset. The planet will set around 8:20 pm local time. Tonight (Sunday) and on Monday the crescent moon will shine to Saturn’s upper left, hiding the underwhelming stars of Aquarius (the Water-Bearer) that surround Saturn.

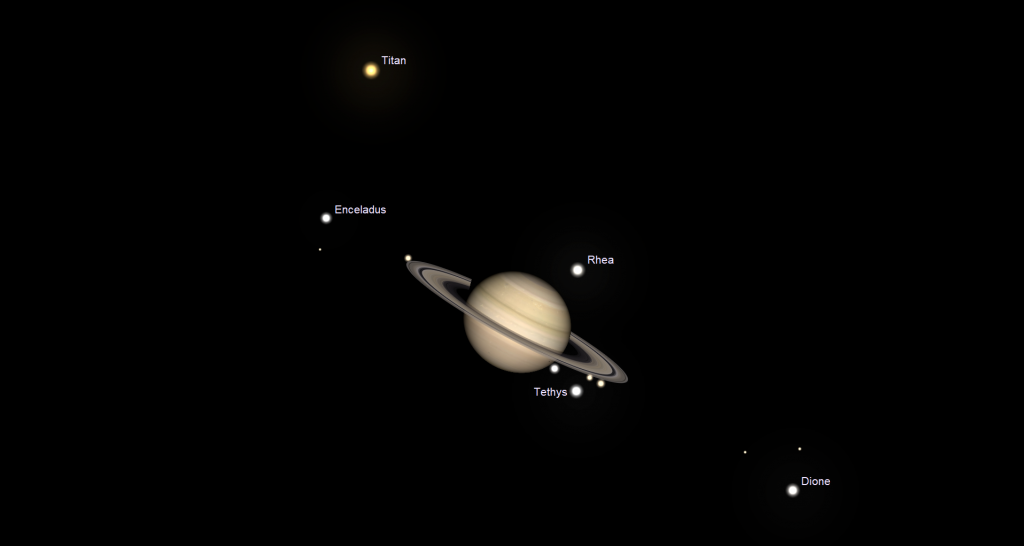

Powerful binoculars can hint that Saturn has rings, but any size, style, or brand of telescope will let you see them easily (for now). A better quality of telescope will show them more clearly. Saturn’s brighter moons array themselves above, below, and to either side the planet. Saturn’s largest and brightest moon Titan never wanders more than five times the width of Saturn’s rings from the planet. The much fainter moon named Iapetus can stray up to twelve times the ring width during its 80-day orbit of Saturn. The next brightest moons Rhea, Dione, Tethys, Enceladus, and Mimas all stay within one ring-width of Saturn.

During this week, Titan will migrate counter-clockwise around Saturn, moving from close-in at the upper left of Saturn (or celestial northeast) tonight, to much farther in that direction at mid-week, and then just to the lower left of the planet (or celestial southeast) next Sunday night. (Remember that your telescope will probably flip the view around.) The rest of the moons will be tiny specks. You may be surprised at how many of them you can see through your telescope if you look closely.

The faint, blue, ice giant planet Neptune is east of Saturn on the ecliptic, so it follows Saturn down in evening, but sets nearly two hours later (around 10 pm local time). The magnitude 7.9 outer planet will be very hard to see this week, especially with the moon parked next door to it on Monday night.

After your rather hurried view of Saturn, you have several hours to enjoy Jupiter. Its extremely bright, white dot will gleam in the south-southeastern sky at dusk and peak telescope-time will arrive around 7 pm, when it will be highest due south. The planet will set in the west by about 1:45 am. Any decent pair of binoculars can show you Jupiter’s four largest Galilean moons lined up on both sides of the planet. Named Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto in order of their orbital distance from Jupiter, those moons complete orbits of the planet every 1.7, 3.6, 7.2, and 16.7 days, respectively. If you see fewer than four moons, then one or more of them is crossing in front of or behind Jupiter, or hiding in Jupiter’s dark shadow – or two of the moons are very close together or occulting one another. In the Americas, all four moons will be huddling to Jupiter’s right on Friday evening. The moons will pair to each side of Jupiter on Thursday and Saturday evening.

Any small, decent quality telescope can show you Jupiter’s dark belts and light zones, which are aligned parallel to its equator. With a better grade of optics, Jupiter’s Great Red Spot, a cyclonic storm that has raged for hundreds of years, is visible for several hours when it crosses the planet every 2nd or 3rd night. For observers in the Americas, the GRS will cross Jupiter’s disk in mid-evening Eastern Time tonight (Sunday) with Io’s shadow, on Tuesday, Thursday, and next Sunday. It’ll appear late on Thursday night, and also around midnight on Monday, Thursday and Saturday. The spot has been rather pale pink for some time now. If you have any coloured filters or nebula filters for your telescope, try enhancing the spot with them.

From time to time, the small, round, black shadows cast by Jupiter’s Galilean moons become visible in amateur telescopes when they cross (or transit) the planet’s disk. For those in the Americas, Io’s shadow will cross Jupiter with the red spot on Sunday, January 21 from 8:10 to 10:14 pm EST (or 01:10 to 03:14 GMT on Monday). (These times may vary by a few minutes, and other time zones of the world will have their own crossings.)

Uranus is following Jupiter across the sky every night and setting before 3 am local time. This week the blue-green planet will be positioned 1.2 fist diameters to Jupiter’s left (or 12° to its celestial ENE). The bright Pleiades star cluster will be located a generous fist’s width to Uranus’ upper left (or 11.5° to its celestial northeast). Magnitude 5.7 Uranus is normally quite easy to see in binoculars and backyard telescopes under moonless conditions, but the moon will interfere with that this week.

Continuing my recent coverage of Vesta, that large, main belt asteroid will be creeping away from the medium-bight star Zeta Tauri (aka Tianguan), the lower horn tip star of Taurus (the Bull) this week. At magnitude 6.4, Vesta is brighter than Neptune and almost as bright as Uranus. Tonight (Sunday) it will be located a finger’s width to the upper right (1° to the celestial northwest) of the star and telescope-close to the Crab Nebula or Messier 1. On each subsequent night it will shift farther to Zeta Tauri’s upper right, toward the star Omicron Tauri.

The two inner planets are dancing in the southeastern sky before sunrise. Brilliant Venus will clear the rooftops by about 6 am local time and then remain in sight until sunrise. It will continue is daily descent sunward through the stars of southern Ophiuchus (the Serpent-Bearer). Viewed through a telescope this week, our next-door planet will show a shrinking, overinflated football shape spanning 13 arc-seconds.

On Friday, Mercury reached its widest angle west of the sun. This week it will be descending sunward. You can look for the relatively bright planet shining very low in the southeastern sky to the lower left of much brighter Venus starting around 6:30 am in your local time zone. They’ll be closest together on Wednesday, after which Mercury will outpace it downward. In a telescope Mercury will exhibit a waxing gibbous phase similar to Venus. For eye safety, turn all optics away from the eastern horizon before the sun rises.

Mercury will also be heading towards Mars, which will gradually climb free of the sun and the morning twilight to become visible at mid-northern latitudes starting next month. Folks living close to the tropics will glimpse Mars sooner than others.

The Bright Stars of January

We’re deep into the cold (and hopefully, clear) nights of winter. Maybe it’s the crisp air, but winter’s stars seem to be the brightest stars. We also get to cheat a little because the three top stars of summer are still around in early evening. Here’s your guide to the brightest stars you can see with your unaided eyes (or binoculars) in the evening sky over the next month or so – even when the moon is around. I’ve put their rank (3rd brightest in the night sky, 7th, etc.) in brackets.

Let’s start in the western half of the sky because those stars set first. If you have an unobstructed southwestern horizon, look as soon as it’s dark for bright Fomalhaut “FOH-ma-lawt” (18th) in Piscis Austrinus (the Southern Fish) sitting just above the southwestern horizon. Turning directly west, the three bright corners of the Summer Triangle asterism still shine brightly in the early evening. The lowest of the three is Altair (12th) in Aquila (the Eagle). A bit higher, and about 3.4 outstretched fist diameters to the right of Altair, is Vega (5th) in Lyra (the Lyre). Deneb (19th) sits above and between those two. All three are hot, bluish white stars. Deneb is the tail of Cygnus (the Swan), and you should be able to see the great bird flying head-down into the west – along the Milky Way. Altair and Vega set about 7:15 and 8:50 pm local time, respectively. Deneb sets much later – at about 1 am local time.

Next, turn fully around and look about halfway up the eastern sky. Bright yellowish Capella (6th) is on the left, with orange-ish Aldebaran (14th) located about three fist widths to the right of it. Capella is the brightest star in the large oval constellation of Auriga (“Oar-EYE-gah”) (the Charioteer), while Aldebaran is the baleful red eye of Taurus (the Bull), whose triangular face is tilted sideways with his horns aimed down to the left. Both of these constellations will climb higher as the evening wears on.

The well-known constellation of Orion (the Hunter) sits directly below Aldebaran. His eastern shoulder is the old and bright reddish star Betelgeuse (11th), and his opposite foot is a bluish star of similar brightness named Rigel (7th). These two stars are hundreds of light-years away. Orion’s three-starred belt is a highlight of the winter sky. From east to west (lower left to upper right) they are Alnitak (30th), Alnilam (29th), and Mintaka (67th). The three stars are about evenly spaced – almost exactly 1.3° (about three moon diameters) apart. Orion’s other shoulder is marked by bluish white Bellatrix (26th), and his opposite foot is called Saiph (53rd).

To the left of Orion sits the zodiac constellation of Gemini (the Twins). Its brightest stars are yellowish Pollux (17th) and pale white Castor (23rd). Like many twins, they are a challenge to keep straight which is which. Castor, the higher star, rises first, just as “C” precedes “P” in the alphabet. Unlike identical twins, Castor is both fainter and whiter than Pollux. Gemini also hosts Alhena (43rd), the star that forms Pollux’ higher, western foot.

By about 7:30 pm local time the night sky’s brightest star will clear the trees in the sky below Orion. Sirius (1st) is also called the Dog Star because it resides in the constellation of Canis Major (the Large Dog). It is a very hot, bluish-white star, so bright because it is our neighbour – positioned “just up the street” at only 8.6 light-years away. Sirius has a reputation for twinkling vigorously with flashes of pure colour. This is because it sits fairly low in the sky for mid-northern latitude dwellers and they see it shining through a thicker blanket of refracting air. The big dog hosts three more bright stars, namely Adhara (22nd), Wezen (36th), and Mirzam (46th). They mark his rear leg, rump, and front paw, respectively.

Sirius’ bright little sibling Procyon (8th) sits 25° (2.5 fist widths) to the upper left, underneath Gemini, in the constellation of Canis Minor (the Little Dog). It, too, is relatively close to Earth.

In mid-evening, the bright, white star Regulus (21st), the heart of Leo (the Lion) will rise to join the party.

So, which constellation wins the award for the brightest one? Of the top 50 stars, Orion has five and Canis Major has four. Does Sirius give Canis Major the win? I’ll let you decide. See how many of them you can learn!

Auriga Drives the Chariot

If you missed last week’s tour of Auriga (the Charioteer), l posted it with some photos of its best objects here. In two weeks, after the full moon, I’ll focus on Orion (the Hunter).

Public Astronomy-Themed Events

Every Monday evening, York University’s Allan I. Carswell Observatory runs an online star party – broadcasting views from four telescopes/cameras, answering viewer questions, and taking requests! Details are here. They host in-person viewing on the first clear Wednesday night each month. Other Wednesdays they stream views online via the observatory YouTube channel. Details are here.

On Friday, January 19 from 6:30 pm to 8:30 pm, RASC Toronto Centre will host Family Night at the David Dunlap Observatory for visitors aged 7 and up. You will tour the sky, visit the giant 74” telescope, and view celestial sights through telescopes if the sky is clear. This program runs rain or shine. Details are here, and the link for tickets is here.

On Sunday afternoon, January 21 from 12:30 to 1 pm EDT, head to the David Dunlap Observatory for in-person DDO Sunday Sungazing. Safely observe the sun with RASC Toronto astronomers! During the session, which is for ages 7 and up, a DDO Astronomer will answer your questions about our closest star – the sun! Registrants will be given an eclipse viewer, learn how the sun works and how it affects our home planet, view the sun through solar telescopes, weather permitting, and visit the giant 74” telescope. More information is here and the registration link is here.

Keep your eyes on the skies! I love getting questions and requests. Send me some!